Published online Feb 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i7.870

Peer-review started: November 14, 2018

First decision: January 6, 2019

Revised: January 17, 2019

Accepted: January 26, 2019

Article in press: January 26, 2019

Published online: February 21, 2019

Processing time: 100 Days and 11.6 Hours

The caustic ingestion continues to be a major problem worldwide especially in developing countries. The long-term complications include stricture and increased life time risk of oesophageal carcinoma. Patients suffered from corrosive induced oesophageal strictures have more than a 1000-fold risk of developing carcinoma of the oesophagus.

To determine the possibility of oesophageal mucosal dysplasia after prolonged dilatation in post corrosive stricture.

This observational study was conducted at the Paediatric Endoscopy Unit in Cairo University Children’s Hospital. It included children of both sexes older than 2 years of age who had an established diagnosis of post-corrosive oesophageal stricture and repeated endoscopic dilatation sessions for more than 6 mo. All patients were biopsied at the stricture site after 6 mo of endoscopic dilatation. A histopathological examination of an oesophageal mucosal biopsy was performed for the detection of chronic oesophagitis, inflammatory cellular infiltration and dysplasia.

The mean age of the enrolled children was 5.9 ± 2.6 years; 90% of the patients had ingested an alkaline corrosive substance (potash). The total number of endoscopic dilatation sessions were ranging from 16 to 100 with mean number of sessions was 37.2 ± 14.9. Histopathological examination of the specimens showed that 85% of patients had evidence of chronic oesophagitis (group A) in the form of basal cell hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and subepithelial fibrosis. Thirteen percent of the patients had evidence of reactive atypia (group B) in the form of severe neutrophilic intraepithelial inflammatory cellular infiltration, and 2 patients (2%) had mild squamous dysplasia (group C); we rebiopsied these two patients 6 mo after the initial pathological assessment, guided by chromoendoscopy by Lugol's iodine.

The histopathology of oesophageal mucosal biopsies in post-corrosive patients demonstrates evidence of chronic oesophagitis, intraepithelial inflammatory cellular infiltration and dysplasia. Dysplasia is one of the complications of post-corrosive oesophageal stricture.

Core tip: Caustic ingestion continues to be a significant problem worldwide especially in developing countries. It has been reported that the accidental corrosive substance ingestion is seen mostly among children younger than 5 years of age. Corrosive ingestion in children may cause clinical manifestations varying from no injury to fatal outcome, including the risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. In this study, we analyzed our single-center experience, representing the largest series of paediatric patients with post-corrosive oesophageal stricture on repeated endoscopic dilatation sessions for more than 6-mo duration and histopathological examination of oesophageal mucosal biopsies were performed.

- Citation: Eskander A, Ghobrial C, Mohsen NA, Mounir B, Abd EL-Kareem D, Tarek S, El-Shabrawi MH. Histopathological changes in the oesophageal mucosa in Egyptian children with corrosive strictures: A single-centre vast experience. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(7): 870-879

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i7/870.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i7.870

Oesophageal stricture due to corrosive injury has been cited as a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus[1]. The possibility and pathogenesis of the increased risk of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma following caustic injury remain uncertain[2]. The incidence of cancer in patients with corrosive strictures has been estimated to be 2.3% to 6.2%, and a history of caustic ingestion was present in 1% to 4% of patients with oesophageal cancer[3]. Neither dilatation treatment nor oesophageal bypass surgery can prevent the development of oesophageal carcinoma, the incidence of which is high after caustic substance ingestion[4]. Malignant transformation should be suspected in patients with longstanding corrosive ingestion if there is a change in their symptoms, as early diagnosis can improve the outcome[5]. It was found that genetic factors play a minor role in the pathogenesis of oesophageal cancer[6,7]. Epithelial dysplasia has been assumed to be a precancerous lesion of the oesophagus, which is usually preceded by chronic oesophagitis[8,9]. The most frequently encountered histopathological changes in patients with post-corrosive stricture are epithelial hyperplasia, focal hyperkeratosis, and mixed inflammatory exudates in the subepithelium[1]. Considering that oesophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD) is the pre-neoplastic lesion for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) provides the possibility of not only screening for early stage ESCC but also screening for and treating the pre-neoplastic lesion itself[10]. Chromoendoscopy with Lugol’s iodine staining efficaciously identifies subjects with dysplasia[11]. The negative- image "unstained lesions" (USLs) after spraying iodine can be endoscopically targeted for biopsy and/or focal endoscopic therapy[10]. The routine endoscopic biopsy of normal- appearing mucosa or biopsies guided by tissue staining with Lugol’s solution may increase the detection of dysplasia or early oesophageal cancer[12]. This study was designed to screen post-corrosive children for the risk of development of oesophageal mucosal dysplasia to assess the safety of prolonged endoscopic dilatation of post-corrosive oesophageal stricture.

The present study is an observational study that included 100 children with an established diagnosis of post-corrosive oesophageal stricture who were engaged in repeated endoscopic dilatation sessions for more than 6 months. The study was conducted at the Paediatric Endoscopy Unit, Cairo University Paediatric Hospital, from March 2015 to September 2016.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Paediatrics Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt. The research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All patients were enrolled in the study after informed consent was obtained from their parent/guardian.

The age of the enrolled patients of both sexes was older than 2 years. We excluded infants younger than 2 years of age and those with other causes of oesophageal stricture, e.g., post-tracheo-oesophageal fistula repair, congenital oesophageal stenosis, post-sclerotherapy and prolonged nasogastric intubation, peptic stricture, post-chemotherapy or radiotherapy stricture, and epidermolysis bullosa, as well as post-corrosive patients who had surgical repair either in the form of a colon bypass or gastric tube placement.

All patients were subjected to a full clinical assessment focusing on the age of onset of ingestion of the corrosive substance, type of corrosion, age at the time of enrolment in the study and number of dilation sessions. The patients’anthropometric measurements (weight, height), which were plotted on Egyptian growth curves (Standard Egyptian Growth, 2008), and the corresponding z-scores were obtained. All patients were evaluated via a barium swallow on the 21st post-ingestion day. A medium density barium sulfate mixture was used for the single-contrast examination. Fluoroscopic spot films of the oesophagus, as well as overhead films (35.5 cm × 43 cm) in the anteroposterior and lateral positions, were obtained to determine the extent, length, and number of the strictures. Patients were advised to come to the endoscopy unit after 6 h of fasting. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed using a Silver Karl Storz Endoskope 13821 PKS with Storz Professional Image Enhancement System (SPIES) technology with an HD system and 100-watt xenon light source. Endoscopic bougie dilatation was performed using Savary Gilliard dilators (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, United States). An endoscope was first introduced to evaluate the anatomy, and bougies in sequentially increasing sizes were then passed over the guide wire that had been positioned with the tip in the gastric antrum. The initial dilator chosen should have been based on the known or estimated stricture diameter. To avoid complications in the early stage of oesophageal stricture, the sizes of the dilators used were usually 7, 9, 10, 11, and 12.8 mm. After the final dilation, endoscopy was performed to assess the efficacy of the dilatation as well as complications such as bleeding or perforation of the oesophagus. After the dilation procedures, the patients remained fasting and were followed up for 2 h. The patients received anti-reflux treatment in between the dilatation sessions. The treatment was considered effective when patients were able to eat semi-solid or solid foods without dysphagia. The biopsy was performed after 6 mo of regular endoscopic dilation. Using biopsy forceps, the mucosal biopsies were procured from the stricture site during the endoscopic examination before dilation. All specimens were processed as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks. Each block was cut into 5-μm-thick serial sections, which were mounted on glass slides. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Stained sections were then examined using light microscopy. Under light microscopy, the examined sections were graded on a scale of 0-3 (0, absent; 1, mild; 2,moderate; 3, severe) according to the following parameters that were measured and recorded: thickness of the epithelial layer, basal cell hyperplasia(15%-20% of epithelial thickness), length of the papillae (> 1/3 the epithelial thickness), hyperkeratosis, amount of cytoplasm, nuclear atypia, nuclear/cytoplasm ratio, intraepithelial neutrophils, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, koliocytic and hydropic changes, intraepithelial vascular spaces, subepithelial fibrosis and squamous dysplasia. Each variable was graded as follows: low grade (abnormal cells limited to the basal half of the epithelium), high grade (abnormal cells present in the upper half) and indefinite for dysplasia (reactive epithelial atypia associated with a severe inflammatory reaction). There are two pathologists in this study. The pathologist No. 1 examined all of histology specimens. The pathologist No. 2 had just evaluated a part of histology specimens. Patients who had low-grade dysplasia were subjected to rebiopsy via chromoendoscopy after a period that ranged from 6 mo to one year from the initial pathological assessment. In the current study, Lugol's iodine solution was used to detect the dysplastic areas of the mucosa, and it was sprayed onto the oesophageal surface from the gastro-oesophageal junction to the upper oesophageal sphincter using the dye-spraying catheter through the biopsy channel. The use of Lugol's iodine ensured that the USLs were clearly visible after 5 min, allowing enough time for photographs to be recorded and biopsies to be conducted. From each unstained or lightly stained lesion, between one and three biopsies were collected for histopathological examination. The findings were recorded in tabular form. The group of patients who suffered from reactive epithelial atypia associated with a severe inflammatory reaction were followed regularly in our endoscopy unit, and a rebiopsy was subsequently planned.

Pre-coded data were entered into the computer using the Microsoft Office Excel software program (2010) for Windows. Data were then transferred to the Statistical Package of Social Sciences software program, version 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), for statistical analysis. Data are presented as the means and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and as frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. The comparison between groups was performed using the chi-square test for qualitative variables. The one-way ANOVA test and t-test were used to compare group means, which are both parametric statistical methods. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Graphs were used to illustrate some information.

This study included 100 patients, and males represented 63% of the patients. The mean age of the patients was 5.9 ± 2.6 years. The mean age at the time of corrosive ingestion was 2.1 ± 1.1 years. The general examination of the patients revealed that the median and range of weight and height by Z-score were -1.20 (-10.81-1.91) and -2.11 (-5.82-0.61), respectively. Forty-seven patients (47%) were no more than the 3rd percentile in weight, while seventy patients (70%) were no more than the 3rd percentile in height (i.e., stunted growth). The majority (90%) of our patients ingested an alkaline substance (potash); 6% of them ingested a neutral substance (chlorine); and only 4% of them ingested an acidic substance (H2SO4). All patients were evaluated on the 21st post-ingestion day by barium swallow to determine the site, length and number of strictures. A long segment was determined radiologically by more than the length of two vertebrae, measuring approximately 4 cm. The total number of endoscopic dilatation sessions were ranging from 16 to 100 with mean number of sessions was 37.2 ± 14.9. Biopsy specimens were obtained from the oesophageal stricture site at the time of endoscopic examination before the dilatation using biopsy forceps after at least six-month duration of regular endoscopic dilatation.

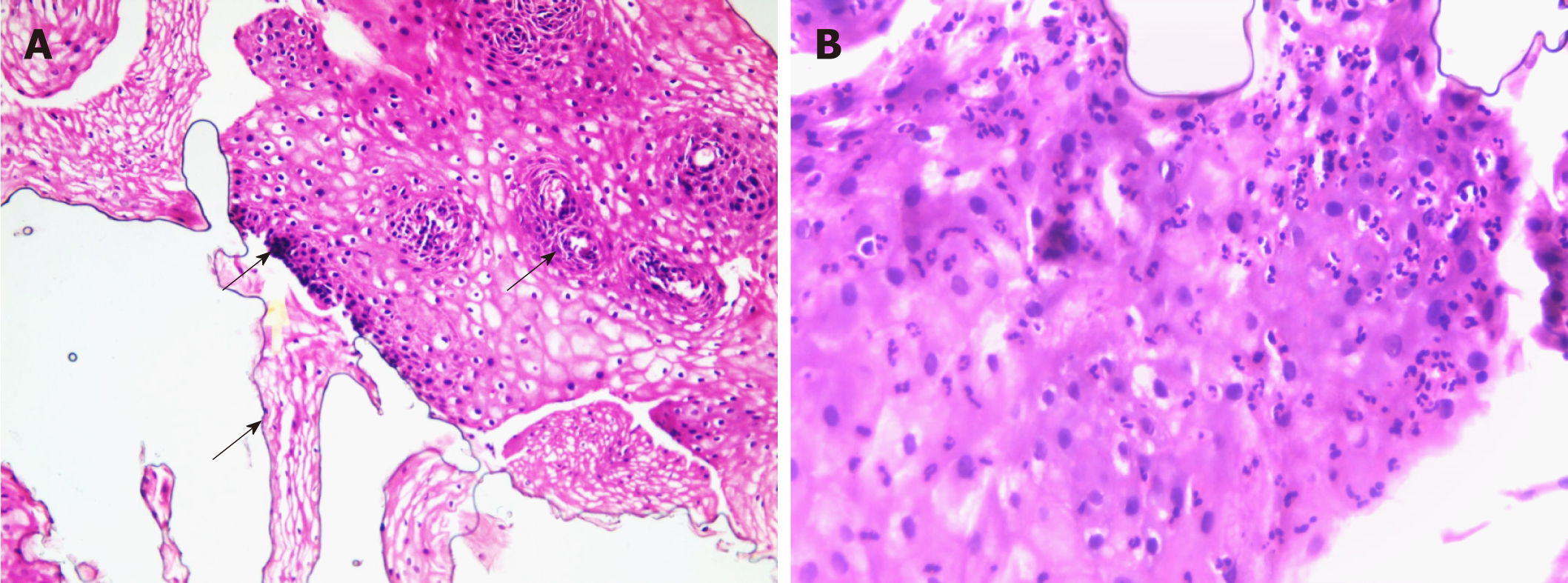

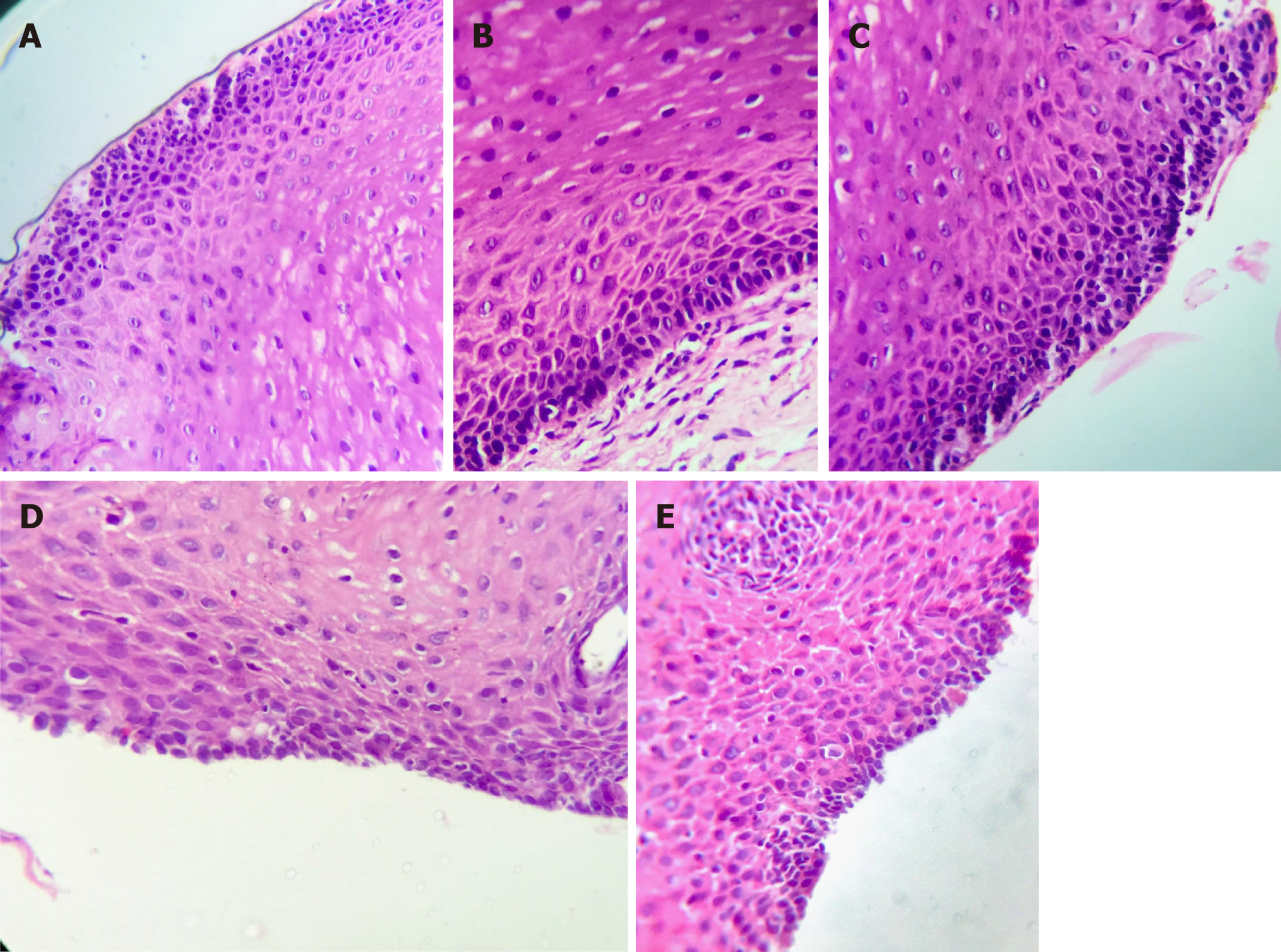

According to the histopathological findings of specimens from the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, the patients were subdivided into three groups, as shown in Figures 1-3, and Table 1.

| Variable | Group A | Group B | Group C | P value | |||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 52 | 61.2 | 9 | 69.2 | 2 | 100 | 0.469 |

| Female | 33 | 38.8 | 4 | 30.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Age at time of enrolment (yr) | 5.60 ± SD 2.50 | 8.08 ± SD 2.18 | 8.75 ± 6.01 | 0.002 | |||

| Age of corrosive ingestion In years | 1.94 ± SD 0.66 | 2.27 ± SD 0.44 | 6.25 ± SD 6.72 | < 0.001 | |||

| Type of corrosion | |||||||

| Alkaline | 78 | 91.8 | 10 | 76.9 | 2 | 100 | 0.005 |

| Neutral | 6 | 7.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Acidic | 1 | 1.2 | 3 | 23.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Weight in percentile | |||||||

| < 3rd | 38 | 44.7 | 9 | 69.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.104 |

| > 3rd | 47 | 55.3 | 4 | 30.8 | 2 | 100 | |

| Height in percentile | |||||||

| < 3rd | 61 | 71.8 | 9 | 69.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.091 |

| > 3rd | 24 | 28.2 | 4 | 30.8 | 2 | 100 | |

| Stricture site | |||||||

| Upper esophageal | 74 | 87.1 | 12 | 92.3 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.253 |

| Mid esophageal | 53 | 62.4 | 10 | 76.9 | 2 | 100 | 0.341 |

| Lower esophageal | 3 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.761 |

| Stricture length | |||||||

| Long segment | 59 | 69.4 | 13 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0.045 |

| Short segment | 26 | 30.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Stricture number | |||||||

| Single | 45 | 52.9 | 4 | 30.8 | 2 | 100 | 0.124 |

| Multiple | 40 | 47.1 | 9 | 69.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Number of dilatation | 35.21 ± 12.79 | 49.38 ± 21.81 | 42.50 ± 17.68 | 0.005 | |||

| Duration since ingestion in years | 3.66 ± 2.20 | 5.81 ± 2.41 | 2.50 ± 0.71 | 0.004 | |||

| No further dilatation | 43 (50.5%) | 11 (84.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.015 | |||

| Ongoing dilatation | 42 (49.5%) | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (100%) | ||||

Group A: Eighty-five patients (85%) had evidence of chronic oesophagitis in the form of hyperplastic mucosa, basal cell hyperplasia, intraepithelial inflammatory cells, dilated vascular spaces, hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, hydropic changes, and subepithelial fibrosis.

Group B: Thirteen patients (13%) had evidence of reactive epithelial atypia/indefinite for dysplasia with heavy neutrophilic, intraepithelial, and inflammatory cell infiltration.

Group C: Only two patients (2%) had low-grade squamous dysplasia.

The pathologist No. 2 had just evaluated a part of histology specimens, and all results were the same except for minor differences in few patients as described below. Patient No. 9, pathologist No. 1 described his biopsy as chronic oesophagitis indefinite for early dysplastic changes, while pathologist No. 2 described it as low grade dysplasia with evidence of epithelial cell disorganization, nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromasia and cellular crowding. Chromoendoscopy was decided for patient No. 9 to obtain targeted biopsy from the dysplastic oesophageal mucosa, both pathologists examined the specimen blindly. The final result was the same for both pathologists as low grade dysplasia.

Patient No. 33 and 45, pathologist No. 1 described their biopsy as chronic oesophagitis, while pathologist No. 2 described their biopsy as reactive epithelial atypia / indefinite for dysplasia due to heavy intraepithelial neutrophilic infiltration.

The majority (90%) of our patients ingested an alkaline substance (potash), while 6% of them ingested a neutral substance (chlorine) and only 4% ingested an acidic substance (H2SO4). This result may be attributed to the fact that in liquid form, bases are tasteless and denser than water[13], while strong acids are bitter and are commonly expectorated[4]. Potash is potassium hydroxide, it used in oven cleaners, liquid agents, liquid drain cleaners, disk batteries household cleaners, dishwater detergents[12,13]. The median and range of patients’ weight and height by Z-score were -1.20 (-10.81-1.91) and -2.11 (-5.82-0.61), respectively. Forty-seven of the patients (47%) were no more than the 3rd percentile in weight, while seventy patients (70%) were no more than the 3rd percentile in height, which reflects stunted growth and nutritional compromise as a complication of corrosive stricture[14]. Bouginage using Savary-Gilliard or American type of technique, irrespective of the type and the extent of oesophageal stenosis, is safe and purposeful procedure[15,16]. We used bougie dilators for three reasons; 74% of our patients had long segment oesophageal stricture, we unified the method of dilation for all included patients to avoid the confounding variables and due to financial issues in our LMIC’s, balloon dilators are an expensive, especially it was single use method. The oesophageal stent was not available in our institute due to financial issues. In the present study, the histopathological findings of endoscopic oesophageal biopsies revealed that eighty-five patients (85%) had evidence of chronic oesophagitis and irritation in the form of basal cell hyperplasia, intraepithelial vascular spaces, hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, hydropic changes, and subepithelial fibrosis, in accordance with the results obtained by Nagaich et al[1], who reported that epithelial hyperplasia, focal hyperkeratosis, and mixed inflammatory exudates in the subepithelium were the predominant histological findings of the biopsies in caustic oesophageal stricture patients. More than half (50.5%) in this group was healed and required no further dilatation. In this study, the definite diagnosis of dysplasia was difficult in thirteen of our patients (13%) who were classified as reactive epithelial atypia/indefinite for dysplasia due to the heavy inflammation and neutrophilic intraepithelial inflammatory cellular infiltration. This group of patients was being followed regularly, and a biopsy was subsequently planned for these patients. This was similarly stated by Attila et al[17], who said that the presence of intraepithelial inflammatory cellular infiltration is well recognized by pathologists to be a confounding factor in the diagnosis of dysplastic lesions, as inflammation causes reactive changes within the cells, which can be very similar to that of dysplasia. Eleven out of thirteen in this group was healed and required no further dilatation. In the present study, only two patients (2%) had low-grade dysplasia and underwent a three-year period of dilatation; one of them was 14 years of age, and the other patient was five years of age. They are still on regular endoscopic dilatation sessions. Other studies reported that the incidence of cancer in patients with corrosive strictures has been estimated to be 2.3% to 6.2%, and a history of caustic ingestion was present in 1% to 4% of the patients with oesophageal cancer in the study of Isolauri et al[3]. However, another study by Nagaich et al[1] revealed no cases of dysplasia reported on histopathological examination of endoscopic biopsies from patients older than 3 years of age with caustic oesophageal strictures who had undergone more than 10 years of dilatation[1]. This result may be explained by the statement of Allam et al[6] that children do not experience a long enough period of chronic oesophagitis to reach a state of dysplasia. Kavin et al[18] the initial biopsy before the first bougie dilatation in post corrosive patients revealed very minimal histopathological abnormalities, suggesting the possibility that the trauma of repeated bougie dilatation may be a promoter in the ultimate development of dysplasia. This finding is in accordance with this study. Specifically, patients with evidence of reactive atypia or low-grade dysplasia on histopathological examination of their biopsies had a greater mean number of endoscopic dilatation sessions; however, statistical significance was not achieved. However, patients with evidence of chronic oesophagitis had a significantly lower mean number of endoscopic sessions (P < 0.05). In 2015, Nagaich et al[1] studied the histopathological changes and safety of chronic dilatation (mean duration of 10 years) in reference to the occurrence of dysplastic changes and reported no risk from chronic dilatation. This result enforced the safety of repeated endoscopic dilatation in our study; no statistical significance was found between the pathological criteria (i.e., chronic irritation, reactive epithelial atypia, or low-grade dysplasia) of the oesophageal mucosal biopsies in the three groups and duration of endoscopic dilatation of more than two years. There is a long latency period (12-41 years) between ingestion of caustics and the development of malignancy[6,19,20]. Jain et al[20] reported the first case from India of a 14-year-old boy with an associated 1-year history of accidental caustic ingestion who developed ESCC along with cervical lymph node metastasis. In this study, the duration since corrosive ingestion was 3.5 and 3 years in two cases with mild-grade dysplasia. Karwasra et al[8] and Zhen et al[9] reported that dysplasia is a precancerous lesion of ESCC, which is usually preceded by chronic oesophagitis. The aim of this study was to assess the risk of development of premalignant lesions and the value of screening for any premalignant lesions in individuals who are susceptible after a long duration of corrosive ingestion or prolonged endoscopic dilatation. In 2013, Taylor et al[10] reported that ESD appears to progress over months to many years, depending on the grade. It is probable that severe dysplasia needs prompt treatment, moderate dysplasia needs treatment or periodic endoscopic follow-up and mild dysplasia can be followed at longer intervals. So, we re- biopsied the two patients who had mild-grade dysplasia by the use of chromoendoscopy. The Lugol's iodine solution used to detect the dysplastic areas of mucosa was sprayed onto the oesophageal surface from the gastro-oesophageal junction to the upper oesophageal sphincter using the dye-spraying catheter through the biopsy channel. This protocol is in agreement with the methods of Chibishew et al[12], who reported that the routine endoscopic biopsy of normal-appearing mucosa or biopsies guided by tissue staining with Lugol’s solution may increase the detection of dysplasia or mild oesophageal cancer. Narrow band imaging- magnifying endoscopy helps in visualization of oesophageal mucosa and surveillance of oesophageal precancerous lesions[21].

In conclusion, the histopathological examination of oesophageal mucosal biopsies in post-corrosive patients demonstrates evidence of chronic oesophagitis, intraepithelial inflammatory cellular infiltration and dysplasia. Dysplasia is a serious complication of post-corrosive oesophageal stricture for which screenings should be performed. The development of dysplasia was associated with several risk factors, but the number of dilatation sessions and duration since ingestion of the corrosive substance were not significantly associated with the risk of dysplasia development.

High attention should be taken from the parents to avoid the availability of the corrosive substances in reachable areas for their kids. Chemical substances should not be stored in food containers. Implementation of preventive programme is very crucial to limit the use of corrosive materials. The use of other methods to detect oesophageal dysplasia, such as P53 immunohistochemical staining of the oesophageal mucosa, allows a more accurate diagnosis of dysplastic lesions, especially in the group of reactive atypia/ indefinite for dysplasia. Other suggestions for further research include the determination of molecular characteristics and genetic risk factors that may predispose individuals to oesophageal dysplasia.

Caustic ingestion continues to be a major health hazard in developed and developing countries despite continuing educational programs and legislation limiting the strength and availability of corrosive substances. It has been reported that the accidental corrosive substance ingestion is seen mostly among children younger than 5 year of age. Corrosive strictures are usually managed by endoscopic dilatation. The target is to dilate oesophageal strictures to a level that allows patients to tolerate a regular diet without dysphagia. The research in paediatric age group was very deficient so we are concerning about the histopathological changes in post corrosive oesophageal stricture in paediatric age and safety of endoscopic dilatation.

Dysplasia has been postulated to be a precancerous lesion of the oesophagus, which in turn is considered to be preceded by chronic oesophagitis. Patients with corrosive induced oesophageal strictures have more than a 1000-fold risk of developing carcinoma of the oesophagus. The incidence of cancer in corrosive strictures has been estimated to be 2.3% to 6.2%, and a history of caustic ingestion was present in 1% to 4% of patients with oesophageal cancer. Risk factors of oesophageal dysplasia in post corrosive stricture were chronic irritation at the site of the scar, local chronic inflammatory responses in the oesophageal mucosa, long latency period from the corrosive ingestion and genetics playing a minor role. The diagnosis of corrosion cancer should be suspected in patients with corrosive ingestion if after a latent period of negligible symptoms there is development of dysphagia, poor response to dilatation, or if respiratory symptoms develop in an otherwise stable patient of oesophageal stenosis. The significance of this study was to set strategy provide early detection of dysplastic changes of oesophageal mucosa in post corrosive stricture. The determination of oesophageal dysplasia which is the pre-neoplastic lesion for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma provides the possibility of screening not just for early stage oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, but also to screen for and treat the pre-neoplastic lesion itself.

The main objectives were to detect the possibility of oesophageal mucosal dysplasia after prolonged dilatation of post corrosive oesophageal stricture and to assess the relationship between duration since the corrosive ingestion and number of oesophageal dilatation sessions with degree of oesophageal mucosal dysplasia.

The work was carried out at the Paediatric Endoscopy Unit in Cairo University Children’s Hospital, from March 2015 to September 2016. The study included the patients older than 2 years of age who had established diagnosis of post corrosive oesophageal stricture on repeated endoscopic dilatation sessions for more than of six-month duration; of both sexes. Infants below 2 year and other causes of oesophageal stricture were excluded. Data included: history taking; age of onset of ingestion of corrosion, type of corrosion, age at the time of enrollment in the study, number of dilation sessions. Clinical examination included Anthropometric measures. All patients were evaluated on the 21st post ingestion day with a barium swallow. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic dilatation of oesophageal stricture was done for all patients with biopsy from the stricture site after at least six-month duration of regular endoscopic dilatation. Histopathological examination of oesophageal mucosal biopsy was performed for detection of chronic oesophagitis, inflammatory cellular infiltration and dysplasia. As regard the patients who had early grade dysplasia, we rebiopsied them after period of time ranged from 6 months to one year from the initial pathological assessment but with the use of the chromoendoscopy by Lugol's iodine.

This study included 100 patients, and males represented 63% of the patients. The mean age of the patients was 5.9 ± 2.6 years. The mean age at the time of corrosive ingestion was 21 ± 1.1 years. The general examination of the patients revealed that the median and range of weight and height by Z-score were -1.20 (-10.81-1.91) and -2.11 (-5.82-0.61), respectively. The majority (90%) of our patients ingested an alkaline substance (potash); 6% of them ingested a neutral substance (chlorine); and only 4% of them ingested an acidic substance (H2SO4). The total number of endoscopic dilatation sessions were ranging from 16 to 100 with mean number of sessions was 37.2 ± 14.9. Biopsy specimens were obtained from the oesophageal stricture site at the time of endoscopic examination before the dilatation using biopsy forceps after at least six-month duration of regular endoscopic dilatation. According to the histopathological findings of specimens from the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, group A: eighty-five patients (85%) had evidence of chronic oesophagitis, group B: thirteen patients (13%) had evidence of reactive epithelial atypia/indefinite for dysplasia, group C: only two patients (2%) had low-grade squamous dysplasia. The pathological follow up of two patients with low grade squamous dysplasia revealed the same grade of dysplasia. The patients with dysplasia should be followed up every year to evaluate the degree of deterioration as well as the group of patients with reactive atypia.

This observational study is a single centre vast experience in which huge number of young children with post corrosive oesophageal stricture was screened for histopathological changes in oesophageal mucosa after long period of endoscopic dilatation. Oesophageal squamous dysplasia could be occurred in that young age. It has been reported that the accidental corrosive substance ingestion is seen mostly among children younger than 5 years of age. Corrosive ingestion in children may cause clinical manifestations varying from no injury to fatal outcome, including the risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. The endoscopic dilatation is considered the safest method for management of paediatric post corrosive stricture. Chronic oesophagitis is the most common histopatholgical findings in post corrosive patients. Dysplasia is one of the complications of post corrosive oesophageal stricture. The development of dysplasia had several risk factors but the number of dilatation session and duration since ingestion of corrosive substance didn't show statistically significant relation with development of dysplasia. Immense the awareness of patients with corrosive ingestion to report if after a latent period of negligible symptoms, there is development of dysphagia, or poor response to dilatation. This needs prompt medical consultation. Aim was to allow the early dignosis of dysplasia or cancer. We reported cases had low grade of dysplasia in spite of young age of patients included in the study. Long term follow up of the patients who had early grade dysplasia is mandatory for the future following years. To screen who became deteriorated to high grade dysplasia or carcinoma in situ with prompt treatment plan.

High attention should be taken from the parents to avoid the availability of the corrosive substances in reachable areas for their kids. Chemical substances should not be stored in food containers. Implementation of preventive programme is very crucial to limit the use of corrosive materials. The use of other methods in future research to detect the oesophageal dysplasia as narrow band imaging technique in endoscopy.

| 1. | Nagaich N, Sharma R, Nijhawan S, Nijhawan M, Nepalia S, Rathore M. Histopathological Profile of Caustic Oesophageal Strictures on Chronic Endoscopic Dilatation: What is the Safe Limit? J Cancer Prev Curr Res. 2015;2:23. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang X, Wang M, Han H, Xu Y, Shi Z, Ma G. Corrosive induced carcinoma of esophagus after 58 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:2103-2105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Isolauri J, Markkula H. Lye ingestion and carcinoma of the esophagus. Acta Chir Scand. 1989;155:269-271. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Uygun I. Caustic oesophagitis in children: prevalence, the corrosive agents involved, and management from primary care through to surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;23:423-432. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kochhar R, Sethy PK, Kochhar S, Nagi B, Gupta NM. Corrosive induced carcinoma of esophagus: report of three patients and review of literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:777-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Allam AR, Fazili FM, Khawaja FI, Sultan A. Esophageal carcinoma in a 15-year-old girl: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2000;20:261-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liang H, Fan JH, Qiao YL. Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Cancer Biol Med. 2017;14:33-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Karwasra RK, Yadav V, Bansal AR. Esophageal carcinoma in a 17-year-old man. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1122-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhen YZ. [Isolation and culture of fungi from the cereals in counties of Henan Province--5 with high and 3 with low incidences of esophageal cancer]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 1984;6:27-29. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Taylor PR, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM. Squamous dysplasia--the precursor lesion for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:540-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dawsey SM, Fleischer DE, Wang GQ, Zhou B, Kidwell JA, Lu N, Lewin KJ, Roth MJ, Tio TL, Taylor PR. Mucosal iodine staining improves endoscopic visualization of squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Linxian, China. Cancer. 1998;83:220-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chibishev A, Markoski V, Smokovski I, Shikole E, Stevcevska A. Nutritional therapy in the treatment of acute corrosive intoxication in adults. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schaffer SB, Hebert AF. Caustic ingestion. J La State Med Soc. 2000;152:590-596. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lupa M, Magne J, Guarisco JL, Amedee R. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of caustic ingestion. Ochsner J. 2009;9:54-59. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Andreevski V, Deriban G, Isahi U, Mishevski J, Dimitrova M, Caloska V, Joksimovic N, Popova R, Serafimovski V. Four Year Results of Conservative Treatment of Benign Strictures of the Esophagus with Savary Gilliard Technique of Bougienage: Cross-Sectional Study Representing First Experiences in Republic of Macedonia. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2018;39:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Geng LL, Liang CP, Chen PY, Wu Q, Yang M, Li HW, Xu ZH, Ren L, Wang HL, Cheng S, Xu WF, Chen Y, Zhang C, Liu LY, Li DY, Gong ST. Long-Term Outcomes of Caustic Esophageal Stricture with Endoscopic Balloon Dilatation in Chinese Children. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:8352756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Attila T, Fu A, Gopinath N, Streutker CJ, Marcon NE. Esophageal papillomatosis complicated by squamous cell carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:415-419. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kavin H, Yaremko L, Valaitis J, Chowdhury L. Chronic esophagitis evolving to verrucous squamous cell carcinoma: possible role of exogenous chemical carcinogens. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:904-914. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Burmeister BH, Walpole ET, Thomas J, Smithers BM. Two cases of oesophageal carcinoma following corrosive oesophagitis successfully treated with chemoradiation therapy. Asia Pacific J Clin Oncol. 2007;3:108-111. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jain R, Gupta S, Pasricha N, Faujdar M, Sharma M, Mishra P. ESCC with metastasis in the young age of caustic ingestion of shortest duration. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee CT, Chang CY, Lee YC, Tai CM, Wang WL, Tseng PH, Hwang JC, Hwang TZ, Wang CC, Lin JT. Narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy for the screening of esophageal cancer in patients with primary head and neck cancers. Endoscopy. 2010;42:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P- Reviewer: Brecelj J, Eleftheriadis NP S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: E- Editor: Huang Y