Published online Oct 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i40.6107

Peer-review started: August 9, 2019

First decision: August 27, 2019

Revised: September 18, 2019

Accepted: September 27, 2019

Article in press: September 28, 2019

Published online: October 28, 2019

Processing time: 79 Days and 23.4 Hours

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has been widely used in pediatric patients with cholangiopancreatic diseases.

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and long-term follow-up results of ERCP in symptomatic pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM).

A multicenter, retrospective study was conducted on 75 pediatric patients who were diagnosed with PBM and underwent therapeutic ERCP at three endoscopy centers between January 2008 and March 2019. They were divided into four PBM groups based on the fluoroscopy in ERCP. Their clinical characteristics, specific ERCP procedures, adverse events, and long-term follow-up results were retrospectively reviewed.

Totally, 112 ERCPs were performed on the 75 children with symptomatic PBM. Clinical manifestations included abdominal pain (62/75, 82.7%), vomiting (35/75, 46.7%), acholic stool (4/75, 5.3%), fever (3/75, 4.0%), acute pancreatitis (47/75, 62.7%), hyperbilirubinemia (13/75, 17.3%), and elevated liver enzymes (22/75, 29.3%). ERCP interventions included endoscopic sphincterotomy, endoscopic retrograde biliary or pancreatic drainage, stone extraction, etc. Procedure-related complications were observed in 12 patients and included post-ERCP pancreatitis (9/75, 12.0%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1/75, 1.3%), and infection (2/75, 2.7%). During a mean follow-up period of 46 mo (range: 2 to 134 mo), ERCP therapy alleviated the biliary obstruction and reduced the incidence of pancreatitis. The overall effective rate of ERCP therapy was 82.4%; seven patients (9.3%) were lost to follow-up, eight (11.8%) re-experienced pancreatitis, and eleven (16.2%) underwent radical surgery, known as prophylactic excision of the extrahepatic bile duct and hepaticojejunostomy.

ERCP is a safe and effective treatment option to relieve biliary or pancreatic obstruction in symptomatic PBM, with the characteristics of minor trauma, fewer complications, and repeatability.

Core tip: The research on the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for management of pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM), especially among pediatric patients, is limited. This retrospective, multicenter study aimed to evaluate the overall safety and efficacy of ERCP to treat children with symptomatic PBM. A retrospective review of the clinical characteristics/conditions of 75 pediatric patients who were diagnosed with PBM, specific ERCP procedures, and their long-term follow-up showed that ERCP is safe and effective for treatment of symptomatic PBM, with limited post-procedural complications among pediatric patients.

- Citation: Zeng JQ, Deng ZH, Yang KH, Zhang TA, Wang WY, Ji JM, Hu YB, Xu CD, Gong B. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children with symptomatic pancreaticobiliary maljunction: A retrospective multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(40): 6107-6115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i40/6107.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i40.6107

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a congenital anomaly in which the pancreatic and bile ducts anatomically meet outside the duodenal wall. Normally, the sphincter of Oddi is located at the distal end of the pancreatic and bile ducts and regulates the outflow of bile and pancreatic juice. In PBM, the common channel is so long that the action of the sphincter does not directly affect the pancreaticobiliary junction, allowing reciprocal reflux of pancreatic juices and bile. Additionally, the pancreatic juice refluxes into the biliary tract owing to the higher pressure within the pancreatic duct compared to that in the bile duct; this reflux induces biliary mucosal injury. The stasis of the mixture of pancreatic juice and bile induces various pathological conditions, such as pancreatitis, protein plugs, and biliary dilatation, and increases the incidence of biliary tract cancer[1-3].

Prophylactic excision of the extrahepatic bile duct is a well-established treatment for PBM. However, pediatric patients with PBM often experience additional conditions, such as obstructive jaundice or acute pancreatitis. Therefore, there is a concern that prophylactic surgeries in pediatric patients may increase the risk of postoperative complications[4,5]. Meanwhile, with continuous technical advancements, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is not only regarded as a standard technique for diagnosing PBM but is also used to improve drainage and resolve complications[6-8]. Nonetheless, there is limited research regarding the use of ERCP for the management of PBM, especially for pediatric patients. Herein, we carried out a long-term retrospective multicenter study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ERCP as a treatment for symptomatic PBM.

To evaluate the efficacy of ERCP for pediatric PBM patients, a retrospective multicenter study was conducted at the following three endoscopy centers in China: Shanghai Children’s Medical Center, Ruijin Hospital of Shanghai Jiaotong University, and Shuguang Hospital of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Pediatric patients (≤ 18 years) with PBM who underwent endoscopic therapy in one of these three centers between January 2008 and March 2019 were included in the study.

Patients with symptomatic PBM and those who underwent ERCP for attempted biliary or pancreatic duct decompression performed through endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) or stent drainage were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were the absence of therapeutic ERCP or of the pertinent medical data.

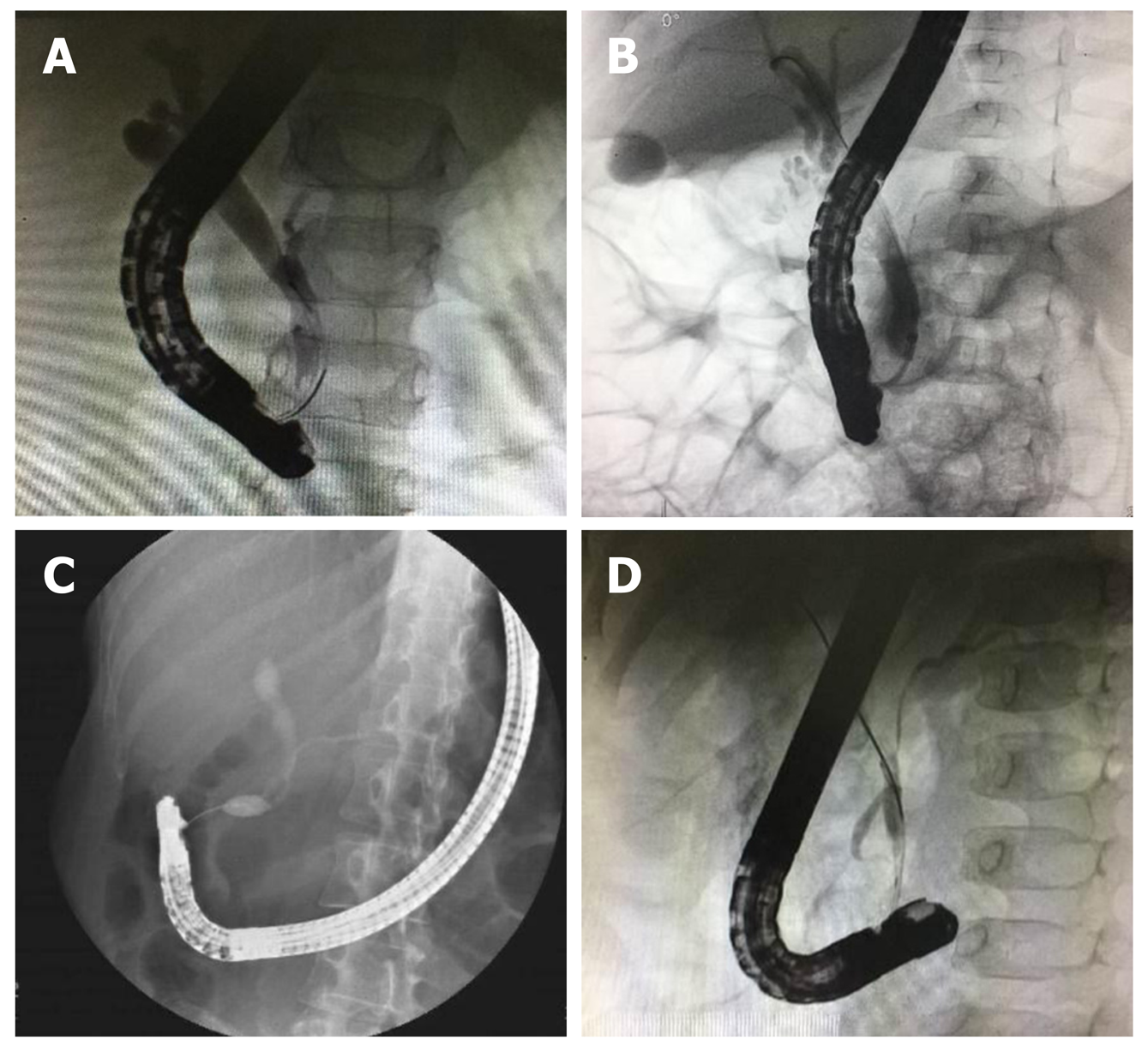

The diagnostic criteria for PBM according to the Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSGPM) include the following definitions: An abnormally long common channel (≥ 6 mm) and/or an abnormal union between the pancreatic and bile ducts that is evident by direct cholangiography under ERCP, and abnormally high levels of pancreatic enzymes in the bile duct and/or the gallbladder that could serve as auxiliary diagnosis. PBM was classified into the following according to the JSGPM criteria[9,10]: (1) Stenotic type; (2) Non-stenotic type; (3) Dilated channel type; and (4) Complex type (Figure 1).

The indications for ERCP intervention are mainly PBM with complications such as biliary pancreatitis, obstructive jaundice, cholangitis, and choledochal dilatation, bile duct calculi, or pancreatic protein plugs suggested by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or ultrasonography.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis was the main complication that was evaluated. It was diagnosed by experienced pediatricians according to the following criteria: Presence of pancreatic pain persisting for at least 24 h and serum amylase level at least 3 times higher than the normal level after ERCP[11].

The risks and benefits of ERCP were clearly explained to the parent(s) or legal guardian(s) of each pediatric patient, and written informed consent was willingly provided by each parent or legal guardian. Initial laboratory tests, including liver function tests, pancreatic enzyme tests, and ultrasound examination or MRCP, were carried out for all patients before an ERCP was performed.

Patients were under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation, and ERCP was performed by experienced doctors. For endoscopy, TJF240 (tip outer diameter, 12.6 mm; channel diameter, 3.2 mm; Olympus) and TJF260 (tip outer diameter, 13.5 mm; channel diameter, 4.2 mm; Olympus) were used for infants and older children, respectively. Depending on the image of endoscopic fluoroscopy, the endoscopists performed EST, bouginage, bile ductal or pancreatic ductal stone extraction, endoscopic nasopancreatic drainage (ENPD), endoscopic retrograde pancreatic drainage (ERPD), endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD), endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD), or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD) to relieve each patient’s symptoms accordingly.

Data are presented as numbers (n) and percentages. Univariate comparisons were made with statistical analysis software 18.0 using chi-squared (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests, depending on statistical distributions. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all P values are two-tailed. The statistical review of this study was performed by a professional biomedical statistician.

Seventy-five pediatric patients with symptomatic PBM were included in the study. There were 23 males and 52 females, with an average age of 6 years (range: 9 mo to 16 years). The most common symptoms that required ERCP were abdominal pain (62/75, 82.7%), vomiting (35/75, 46.7%), acholic stool (4/75, 5.3%), fever (2/75, 2.7%), acute pancreatitis (47/75, 62.7%), hyperbilirubinemia (13 children, 17.3%), and elevated liver enzyme levels (22/75, 29.3%). Some of these patients also exhibited other congenital diseases, such as choledochal cyst (16/75, 12%), pancreatic divisum (7/75, 9.3%), papillary diverticulum (4/75, 5.3%), and diaphragmatic duodenal atresia (2/75, 2.7%) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | n = 75 |

| Age, yr | 6 ± 3.4 |

| Sex, male:female | 23:52 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 62 (82.7) |

| Vomiting | 35 (46.7) |

| Acholic stool | 4 (5.3) |

| Fever | 3 (4.0) |

| Pancreatitis | 47 (62.7) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 13 (17.3) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 22 (29.3) |

| Accompanied diseases, n (%) | |

| Pancreas divisum | 7 (9.3) |

| Papillary diverticulum | 4 (5.3) |

| Diaphragmatic duodenal atresia | 2 (2.7) |

| Choledochal cyst | 12 (16.0) |

| Biliary dilatation | 46 (61.3) |

| Extrahepatic bile duct stones | 44 (58.7) |

| Pancreatic protein plugs | 18 (24.0) |

MRCP or B-scan ultrasonography was performed in all 75 patients before ERCP procedures. Dilatation of the bile duct was detected in 46 (61.3%) subjects, and 44 (58.7%) out of 75 subjects had extrahepatic bile duct stones, which is consistent with ERCP results. However, only 25 (33.4%) of the patients who underwent MRCP or B-scan ultrasonography were diagnosed with PBM.

Using ERCP fluoroscopy, each patient was classified into one of the four PBM types according to the JSGPM PBM classification. Group A comprised 28 patients with stenotic type (type A), group B comprised 27 patients with non-stenotic type (type B), group C comprised 16 patients with dilated common channel type (type C), and group D comprised four patients with complex type (type D). In terms of clinical symptoms, there was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of pancreatitis between these groups, but no difference was noted in other clinical manifestations. PBM with biliary dilatation was observed in 46 (61.3%) patients. Bile duct dilatation and biliary stones were common complications in type A, while pancreatic protein plugs and pancreatic duct stenosis or dilatation were often observed in type C. Pancreatic divisum was observed in three out of the four patients in group D. As group D only included four patients, statistical analysis was not performed to reduce statistical error. Therefore, the P value was the result of comparison between groups A, B, and C (Table 2).

| Type A (n = 28) | Type B (n = 27) | Type C (n = 16) | Type D (n = 4) | P value | |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 5.7 ± 3.2 | 6.6 ± 3.8 | 5.2 ± 3.0 | 6.5 ± 4.2 | 0.398 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 23 (82.1) | 23 (85.1) | 13 (81.2) | 3 (75.0) | 1.000 |

| Vomiting | 12 (44.4) | 13 (48.1) | 8 (50) | 2 (50.0) | 0.867 |

| Acholic stool | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.175 |

| fever | 2 (7.1) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.788 |

| Pancreatitis | 17 (60.7) | 12 (44.4) | 14 (87.5) | 4 (100) | 0.020 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 6 (21.4) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (50.0) | 0.333 |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 12 (42.9) | 4 (14.8) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (75.0) | 0.058 |

| Findings of ERCP, n (%) | |||||

| Bile duct dilatation | 21 (75.0) | 13 (48.1) | 9 (56.2) | 3 (75.0) | 0.122 |

| Biliary stones | 24 (85.7) | 12 (44.4) | 6 (37.5) | 2 (50.0) | 0.001 |

| Pancreatic protein plugs | 1 (3.6) | 5 (18.5) | 11 (68.8) | 1 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Pancreatic duct stenosis or dilatation | 2 (7.1) | 3 (11.1) | 11 (68.8) | 1 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Procedures of ERCP, n (%) | |||||

| EPS | 4 (14.2) | 6 (22.2) | 7 (43.8) | 2 (50.0) | 0.092 |

| EST | 20 (71.4) | 14 (51.9) | 6 (36.5) | 2 (50.0) | 0.017 |

| ERBD | 11 (39.3) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 0.049 |

| ENBD | 12 (42.9) | 13 (48.1) | 7 (43.8) | 1 (25.0) | 0.953 |

| EPBD | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| ENPD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (25.0) | 0.058 |

| ERPD | 2 (7.1) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 0.499 |

| Stone removal | 16 (57.1) | 11 (40.7) | 12 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.088 |

| Bougienage | 2 (7.1) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0.628 |

A total of 112 ERCP procedures were performed on 75 patients with PBM (range: 1 to 5 times per patient), and the technical success rate was 100%. Technical success was defined as the completion of an ERCP operation. The initial therapeutic procedures for each patient included endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy (EPS) (19/75, 25.3%), EST (42/75, 56.0%), ERPD (8/75, 10.7%), ERBD (17/75, 22.7%), ENBD (33/75, 44.0%), EPBD (2/75, 2.7%), ENPD (3/75, 4.0%), stone extraction (40/75, 53.3%), and bougienage (5/75, 6.7%).

The average length of stay in the hospital of all patients was 6 d (range: 3 to 13 d). Regarding clinical complications of ERCP, post-ERCP pancreatitis was observed in nine (12.0%) patients, alimentary tract hemorrhage after EPS was observed in one (1.3%), and fever after operations was observed in two (2.7%). All the 12 patients recovered after conservative treatment. Severe complications, such as periampullary perforation, were not observed. No patient required treatment in the intensive care unit, and hospital mortality was zero.

During an average 46-month (range: 2 to 134 mo) follow-up period with 75 patients, seven (9.3%) patients were lost. Based on the data collected, ERCP therapy could alleviate biliary obstruction and reduce the incidence of pancreatitis. After the exclusion of cases lost to follow-up, the 68 followed children showed significant symptomatic relief, with an overall effective rate of 82.4% (56/68), and no reoccurrence of jaundice or elevated liver enzyme levels was observed in any of the patients after ERCP procedures. Eight (8/68, 11.8%) patients suffered from recurrent pancreatitis, while five of them (5/68, 7.4%) underwent additional ERCP therapy. Eleven patients (11/68, 16.2%) received radical surgery eventually, that is, prophylactic excision of the extrahepatic bile duct and hepaticojejunostomy, for the following reasons: Recurrent pancreatitis after repeated ERCP operations (n = 5), recurrent fever after operations (n = 2), and being concerned about the risk of developing cancer at a later time and requesting the surgery due to personal concerns (n = 4) (Table 3).

| Follow-up details | |

| ERCP-related complications, n (%) | n = 75 |

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | 9 (12.0) |

| Infection | 2 (2.7) |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (1.3) |

| Periampular perforation | 0 (0) |

| Hospital stay, (mean ± SD), d | 6 ± 4.1 |

| Follow-up results1 | |

| Loss to follow-up, n (%) | 7 (9.3) |

| Follow-up period, mean (range), mo | 46 (2-134) (n = 68) |

| Effective rate, n (%) | 56 (82.4) |

| Patients who underwent further ERCP therapy, n (%) | 5 (7.4) |

| Patients who underwent the episode of pancreatitis again, n (%) | 8 (11.8) |

| Patients who underwent radical surgery, n (%) | 11 (16.2) |

| Patients who underwent cholangitis, n (%) | 2 (2.9) |

PBM often causes various hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders among children. The common clinical manifestations of PBM in pediatric patients are acute abdominal pain, vomiting with hyperamylasemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and abnormal liver function. These symptoms usually occur due to higher pressure within the pancreatic duct than that in the bile duct, resulting in stasis of the mixture of pancreatic juice and bile, and the mixture eventually generates protein plugs. Protein plugs are capable of impacting the common channel or terminal portion of the bile duct and obstructing the discharge of bile or pancreatic juice[10,12].

The data from three endoscopy centers were included in our study. Notably, female patients at a high risk for PBM in children comprised 69.3% of the study population. Pediatric patients showed clinical manifestations at an average age of 6 years, with the top pre-ERCP manifestations being pancreaticobiliary calculi, biliary obstruction, and pancreatitis. Meanwhile, PBM was usually accompanied by other congenital malformations, such as choledochal cyst, pancreas divisum, and papillary diverticulum, among pediatric patients. The characteristics of each PBM type in our study are similar to those observed in a survey carried out in Japan[10], with a few differences in proportion.

Mostly, the combination of MRCP and B-scan ultrasonography can provide reliable information for the diagnosis of bile duct/pancreatic duct dilatation, biliary stones, and pancreatic stones[13]. However, they have limited application in the diagnosis of PBM[14-16]. In contrast, ERCP is characterized by a high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing PBM. In the present study, 75 patients underwent MRCP or B-scan ultrasonography tests before ERCP surgery. Only 25 (33.4%) of them were diagnosed with PBM. According to the ERCP results, we concluded that 46 (61.3%) patients had biliary dilatation, 44 (58.7%) had extrahepatic bile duct stones, and 18 (24%) had pancreatic protein plugs.

Published literature on the use of ERCP for PBM is limited, especially among pediatric patients. A relatively large study of 19 pediatric patients with PBM has suggested that ERCP is the logical first step in the management of most symptomatic patients with PBM[17]. In contrast to previous studies, our study included pediatric patients from multiple centers and included follow-up analyses. All patients with PBM were classified into four types according to the JSGPM criteria in the present study. We found that biliary stones were frequently observed in type A PBM patients and may be associated with the stenotic segment of the distal common bile duct. While pancreatitis, pancreatic protein plugs, and pancreatic duct disorders are frequently seen in type C PBM patients, which may be affected by the high-pressure conditions in the expanding common channel.

Apart from diagnosing PBM, ERCP is also useful in performing therapeutic endoscopic treatments. Our study showed that ERCP was an effective treatment option for patients with biliary obstruction. Type A patients usually experience a stenotic bile duct, which could cause biliary obstruction; biliary drainage (ENBD or ERBD) or bougienage was often performed in these patients. For other procedures, no significant differences were seen among the three groups. Patients benefitted from the endoscopic procedures, including EST or EPS, stones removal, and stent insertion to relieve the pancreaticobiliary pressure.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis is the most common complication[18,19]. In this study, procedure-related post-ERCP pancreatitis was observed in nine (12%) cases. The severity of the conditions was mild to moderate, and all patients recovered after conventional conservative treatment. Two (2.7%) patients had fever after the procedure and one (1.3%) child had intestinal hemorrhage after EPS, who eventually recovered after treatment with anti-infection therapy and hemostatic therapy, respectively. No cases of periampullary perforation were observed. According to our experience, it is safe to perform ERCP on pediatric patients, even with drainage and papilla sphincterotomy; severe complications were seldom observed after the ERCP procedures.

In the present study, we followed the cases for an average of 46 mo, with the longest follow-up period being 114 mo, and even lasting until the patient was 25 years old. However, seven patients were lost during follow-up. It can be concluded that ERCP is an option to effectively treat PBM patients with biliary obstruction or pancreatitis. The clinical symptoms can be alleviated after biliary obstruction is treated by ERCP. The effective rate, defined as the percentage of patients remaining asymptomatic for long periods, was as high as 82.4%. However, there were still eight patients with at least one reoccurrence of pancreatitis, and a repeated ERCP was performed in five of them.

The overall incidence of biliary carcinoma with PBM is higher compared to the incidence within the general population. Therefore, prophylactic excision of the extrahepatic bile duct and hepaticojejunostomy are advised for the treatment of PBM[20,21]. In fact, even after corrective surgery for PBM, such patients continue to have a risk of residual bile duct cancer[21-23]. According to the follow-up results of the present study, no patients developed cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer. Further, considering that PBM patients usually become predisposed to develop biliary carcinoma as adults, it may be better to perform surgical resection on PBM patients when they are older. However, in the present study, there were 11 patients who underwent surgical resection after ERCP.

Although the present study provides new information and long-term multicenter follow-up results regarding the application of ERCP on pediatric patients with symptomatic PBM, there are some potential limitations to this study, including its retrospective design. This study design might be underpowered for the detection of differences in outcomes between groups. Furthermore, these procedures were performed at three centers, which might have led to possible selection bias.

Due to its minimal invasiveness and shorter operating duration, EST or biliary drainage by ERCP may be a promising and alternative treatment for symptomatic PBM, especially for children because they face more risks during surgical operations. On the other hand, preoperative ERCP before surgery may benefit PBM patients. At first, ERCP provides detailed information on the pancreaticobiliary systems, and this attributes to the reduction in the number of pancreatitis attacks among PBM patients. Moreover, it could help reduce the risk of malignancy after relieved biliary obstruction. In conclusion, ERCP can serve as a transitional step to definitive surgery for PBM patients. It can guarantee pancreaticobiliary drainage, relieve clinical symptoms, and is only associated with a low incidence of mild complications.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) as an important technological innovation has been used in the field of biliary and pancreatic diseases in children. Pediatric patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) often experience some complications, such as obstructive jaundice or acute pancreatitis. ERCP can be used to improve drainage and resolve complications.

With continuous technical advancements, ERCP is not only regarded as a standard technique for diagnosing PBM but is also used to resolve complications. Nonetheless, there is limited research regarding the use of ERCP for the management of PBM, especially for pediatric patients.

The objective of this study was to retrospectively review the efficacy, safety, and long-term follow-up results of ERCP in symptomatic PBM.

A multicenter, retrospective study was conducted on 75 pediatric patients who were diagnosed with PBM and underwent therapeutic ERCP at three endoscopy centers between January 2008 and March 2019. They were divided into four PBM groups based on the fluoroscopy in ERCP. Their clinical characteristics, specific ERCP procedures, adverse events, and long-term follow-up results were retrospectively reviewed.

A total of 112 ERCPs were performed on the 75 children with symptomatic PBM. Clinical manifestations mainly included abdominal pain, vomiting, acholic stool, fever, acute pancreatitis, hyperbilirubinemia, and elevated liver enzymes. ERCP interventions included endoscopic sphincterotomy, endoscopic retrograde biliary or pancreatic drainage, stone extraction, etc. Procedure-related complications were observed in 12 patients and included post-ERCP pancreatitis (9/75, 12.0%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1/75, 1.3%), and infection (2/75, 2.7%). During a mean follow-up period of 46 mo, the overall effective rate of ERCP therapy was 82.4%, and ERCP therapy can alleviate the biliary obstruction and reduce the incidence of pancreatitis.

As a safe and effective treatment option to relieve biliary or pancreatic obstruction in symptomatic PBM, ERCP is characterized by minor trauma, fewer complications, and repeatability.

Our findings further expanded the application scope of ERCP in biliopancreatic diseases. ERCP can serve as a transitional step to definitive surgery for PBM patients. It can guarantee pancreaticobiliary drainage, relieve clinical symptoms, and is only associated with a low incidence of mild complications. Future prospective studies are needed to investigate the effect of ERCP in patients with PBM to further support our findings.

| 1. | Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Kurata M, Honda G, Tsuruta K, Sasaki T. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S84-S88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ono S, Fumino S, Iwai N. Diagnosis and treatment of pancreaticobiliary maljunction in children. Surg Today. 2011;41:601-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kamisawa T, Honda G. Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction: Markedly High Risk for Biliary Cancer. Digestion. 2019;99:123-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fukuzawa H, Akasaka Y, Maeda K. Dilatation of the common channel in pediatric congenital biliary dilatation remaining after radical operation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26:104-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Martínez-Ródenas F, Torres-Soberano G, Vila-Plana JM, Pie-García J, Catot-Alemany L, Pou-Sanchís E, Hernández-Borlan R, Moreno-Solorzano JE, Guerrero-de-la-Rosa Y, Alcaide-Garriga A, Llopart-López JR. Recurrent acute pancreatitis as a long-term complication of congenital choledochal cyst surgery. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2014;106:230-232. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Jin Z, Bie LK, Tang YP, Ge L, Shen SS, Xu B, Li T, Gong B. Endoscopic therapy for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction: a follow-up study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44860-44869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Halász A, Pécsi D, Farkas N, Izbéki F, Gajdán L, Fejes R, Hamvas J, Takács T, Szepes Z, Czakó L, Vincze Á, Gódi S, Szentesi A, Párniczky A, Illés D, Kui B, Varjú P, Márta K, Varga M, Novák J, Szepes A, Bod B, Ihász M, Hegyi P, Hritz I, Erőss B; Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group. Outcomes and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for acute biliary pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1281-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Krishnamoorthi R, Ross A. Endoscopic Management of Biliary Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:369-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hamada Y, Ando H, Kamisawa T, Itoi T, Urushihara N, Koshinaga T, Saito T, Fujii H, Morotomi Y. Diagnostic criteria for congenital biliary dilatation 2015. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:342-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Urushihara N, Hamada Y, Kamisawa T, Fujii H, Koshinaga T, Morotomi Y, Saito T, Itoi T, Kaneko K, Fukuzawa H, Ando H. Classification of pancreaticobiliary maljunction and clinical features in children. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, Kapral C; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kamisawa T, Kaneko K, Itoi T, Ando H. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and congenital biliary dilatation. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:610-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang CL, Ding HY, Dai Y, Xie TT, Li YB, Cheng L, Wang B, Tang RH, Nie WX. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography study of pancreaticobiliary maljunction and pancreaticobiliary diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7005-7010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Guo WL, Huang SG, Wang J, Sheng M, Fang L. Imaging findings in 75 pediatric patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction: a retrospective case study. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:983-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kamata N. MRCP of congenital pancreaticobiliary malformation. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fumino S, Ono S, Kimura O, Deguchi E, Iwai N. Diagnostic impact of computed tomography cholangiography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography on pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1373-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | De Angelis P, Foschia F, Romeo E, Caldaro T, Rea F, di Abriola GF, Caccamo R, Santi MR, Torroni F, Monti L, Dall'Oglio L. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in diagnosis and management of congenital choledochal cysts: 28 pediatric cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:885-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shih HY, Hsu WH, Kuo CH. Postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019;35:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Attard TM, Grima AM, Thomson M. Pediatric Endoscopic Procedure Complications. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kobayashi S, Ohnuma N, Yoshida H, Ohtsuka Y, Terui K, Asano T, Ryu M, Ochiai T. Preferable operative age of choledochal dilation types to prevent patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction from developing biliary tract carcinogenesis. Surgery. 2006;139:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kamisawa T, Kuruma S, Chiba K, Tabata T, Koizumi S, Kikuyama M. Biliary carcinogenesis in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Watanabe M, Midorikawa Y, Yamano T, Mushiake H, Fukuda N, Kirita T, Mizuguchi K, Sugiyama Y. Carcinoma of the papilla of Vater following treatment of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:6126-6128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aota T, Kubo S, Takemura S, Tanaka S, Amano R, Kimura K, Yamazoe S, Shinkawa H, Ohira G, Shibata T, Horiike M. Long-term outcomes after biliary diversion operation for pancreaticobiliary maljunction in adult patients. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2019;3:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P-Reviewer: Kitamura K, Kozarek RA, Rabago LR S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhang YL