Published online Oct 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i38.5838

Peer-review started: July 16, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: September 5, 2019

Accepted: September 11, 2019

Article in press: September 11, 2019

Published online: October 14, 2019

Processing time: 91 Days and 5.7 Hours

Prolonged postoperative ileus (PPOI) is one of the common complications in gastric cancer patients who underwent gastrectomy. Evidence on the predictors of PPOI after gastrectomy is limited and few prediction models of nomogram are used to estimate the risk of PPOI. We hypothesized that a predictive nomogram can be used for clinical risk estimation of PPOI in gastric cancer patients.

To investigate the risk factors for PPOI and establish a nomogram for clinical risk estimation.

Between June 2016 and March 2017, the data of 162 patients with gastrectomy were obtained from a prospective and observational registry database. Clinical data of patients who fulfilled the criteria were obtained. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were performed to detect the relationship between variables and PPOI. A nomogram for PPOI was developed and verified by bootstrap resampling. The calibration curve was employed to detect the concentricity between the model probability curve and ideal curve. The clinical usefulness of our model was evaluated using the net benefit curve.

This study analyzed 14 potential variables of PPOI in 162 gastric cancer patients who underwent gastrectomy. The incidence of PPOI was 19.75% in patients with gastrectomy. Age older than 60 years, open surgery, advanced stage (III–IV), and postoperative use of opioid analgesic were independent risk factors for PPOI. We developed a simple and easy-to-use prediction nomogram of PPOI after gastrectomy. This nomogram had an excellent diagnostic performance [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.836, sensitivity = 84.4%, and specificity = 75.4%]. This nomogram was further validated by bootstrapping for 500 repetitions. The AUC of the bootstrap model was 0.832 (95%CI: 0.741–0.924). This model showed a good fitting and calibration and positive net benefits in decision curve analysis.

We have developed a prediction nomogram of PPOI for gastric cancer. This novel nomogram might serve as an essential early warning sign of PPOI in gastric cancer patients.

Core tip: Prolonged postoperative ileus (PPOI) is one of the common complications in gastric cancer patients who underwent gastrectomy. Evidence on the predictors of PPOI after gastrectomy is limited. This study investigated the risk factors for PPOI and established an easy-to-use nomogram model for clinical risk estimation. This nomogram had an excellent diagnostic performance and showed superior effects when used in the clinical setting based on the results of the decision curve analysis. This novel nomogram might serve as an essential early warning sign of PPOI for medical practitioners.

- Citation: Liang WQ, Zhang KC, Cui JX, Xi HQ, Cai AZ, Li JY, Liu YH, Liu J, Zhang W, Wang PP, Wei B, Chen L. Nomogram to predict prolonged postoperative ileus after gastrectomy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(38): 5838-5849

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i38/5838.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i38.5838

Postoperative ileus (POI) is an iatrogenic gastrointestinal dysfunction following abdominal surgery[1]. The clinical manifestations of POI are characterized by abdominal distension and pain, nausea and vomiting, lack of bowel sounds, accumulation of gas and fluid, inability to pass stools, and accumulation of gas and fluid[2-6]. Usually, it resolves within 2-4 d, although it may persist for longer days or reoccur. When the symptoms extend beyond the expected duration, it is called prolonged postoperative ileus (PPOI). However, the period of POI to PPOI remains unclear. A systematic review and global survey proposed that PPOI is best defined as ileus that occurs 96 h after surgery based on the results of the previous literature, which has been acknowledged by many investigators[7]. PPOI is a frequent com-plication of abdominal surgery that results in severe disease burden and pain[8,9]. A multicenter survey of 17876 patients undergoing colectomy showed that the frequency of PPOI was 15.3%, which prolonged hospitalization and increased health care resource utilization[10]. However, the majority of the previous studies on PPOI were based on patients referred to colonic or rectal resection, and little data existed on gastrectomy[11,12].

Gastric cancer (GC) is a major health issue worldwide, which remains the third leading cause of cancer death[13]. Immunologic impairment, surgical trauma, inflammatory responses, and tract stasis can increase the frequency of PPOI and bacterial overgrowth and translocation, potentially leading to bacteremia and systemic sepsis[11]. Therefore, to identify the risk indicators for PPOI and determine optimal management strategies, a risk prediction model is urgently required. Of all the available models, a nomogram can provide a highly accurate, individualized evidence-based risk estimation[14,15]. Nomograms predicting survival of patients with unresectable or metastatic GC were well established[16]. To date, various risk indicators have been suggested to be associated with an increased risk of PPOI[17-20]. However, to our knowledge, few prediction models of a nomogram were used to estimate the risk of PPOI after abdominal surgery, especially in patients who underwent radical gastrectomy.

The present study aimed to investigate the pre-, intra-, and postoperative risk factors for PPOI as well as develop and validate a nomogram using clini-copathological variables of patients who underwent radical gastrectomy for GC.

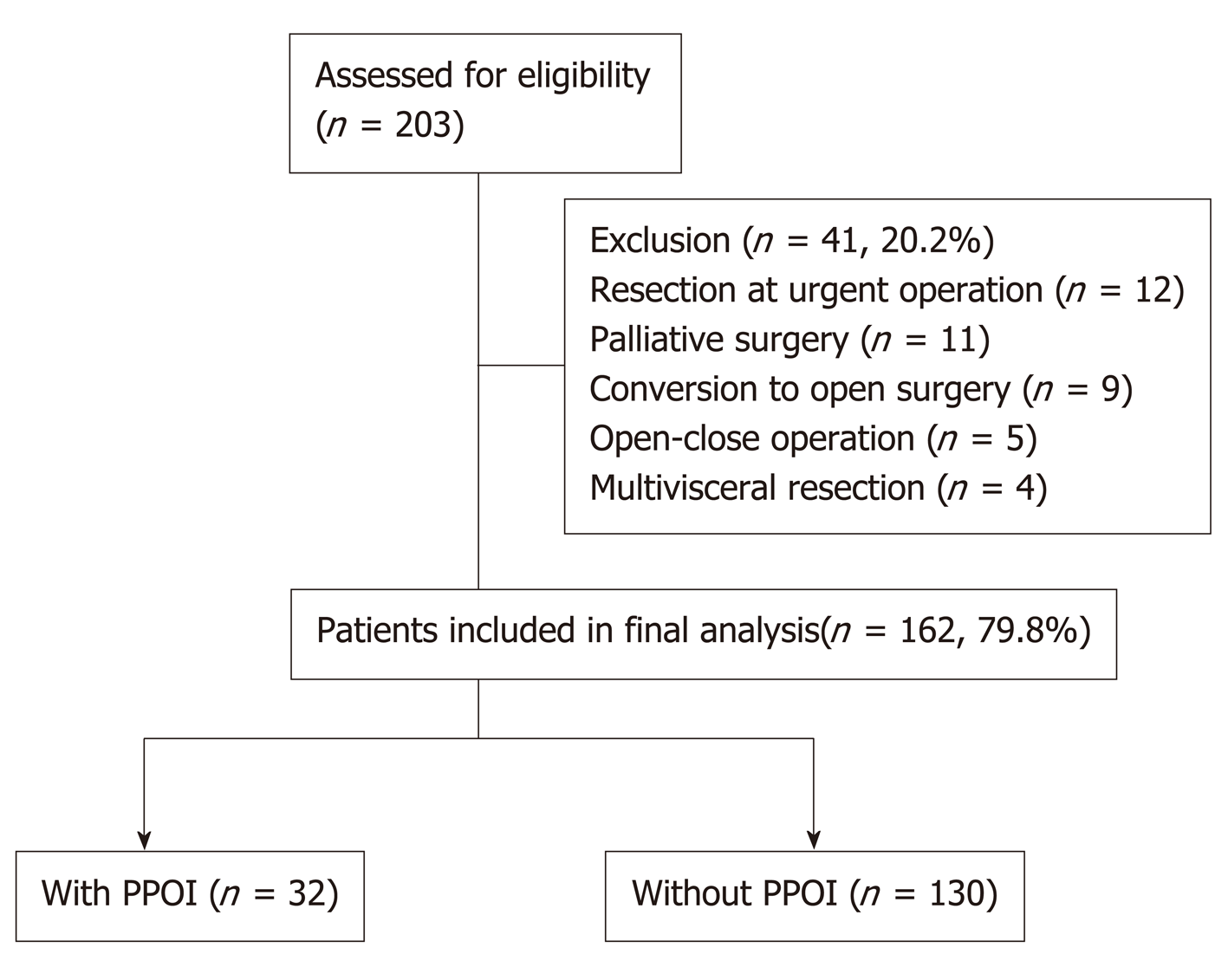

Between June 2016 and March 2017, 203 patients who underwent gastrectomy were identified from a prospectively collected registry database of PPOI in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Hospital. The process for patient selection is presented in Figure 1. Patients diagnosed with resectable gastric cancer who were able to provide written informed consent were eligible for this study. All of the included patients were scheduled to receive gastrectomy with curative intent according to the 2010 Japanese GC treatment guidelines (v. 3)[21]. All resections were performed by a specialized gastric surgical team at the Department of General Surgery, Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. During the study period, 41 patients who underwent the following types of surgery were excluded to avoid the confounding bias: Resection at urgent operation (n = 12), palliative surgery (n = 11), planned laparoscopic surgery converted to open surgery (n = 9), open-close operation (n = 5), and multi-visceral resection (n = 4). Finally, a total of 162 patients were included in the final analysis.

All the included patients were informed of the clinical trial process and signed an informed consent form before surgery. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chinese PLA General Hospital, and all information was obtained with appropriate Institutional Review Board waivers (registration number: S2016-092-01).

A systematic review and global survey proposed a definition of PPOI[7], which was supported by numerous studies[19,22,23]. PPOI was diagnosed if patients met two or more of the following five criteria on day 4 or more postoperatively: Nausea or vomiting for 12 h or more without relief, intolerance to a solid or semi-solid oral diet, persistent abdominal distension, absence of passage of both stool and flatus for 24 h or more, and ileus noted on plain abdominal films or CT scans. We adopted this definition, and the diagnosis of PPOI must independently concur based on two experienced surgeons.

Clinical data of patients who fulfilled the criteria were obtained from the prospective registry database before the assessment of PPOI. Such steps ensured the authenticity and reliability of the data. Patient’s baseline data were collected upon admission as following: Sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and history of previous abdominal surgery. The operation time, surgical bleeding volume, intraoperative blood transfusion, surgical procedure, lymph node dissection, and type of surgical approach (open or laparoscopic) were also obtained. All patients were operated under standard general anesthesia, and the tumor–node–metastasis stage was staged according to the 7th edition of the International Union Against Cancer tumor–node–metastasis classification of malignant tumors. Over the study period, the results of patients’ postoperative physical examination, hematopoietic levels, and biochemical levels were examined within 24 h after surgery. White blood cell (WBC) count and body temperature on the first postoperative day were measured. Patients’ albumin levels improved after receiving postoperative oral feeding and enteric nutrition, which were evaluated in this study. Postoperative potassium plays an essential role in smooth muscle autoregulation and is associated with the development of PPOI[24]. Postoperative potassium level was monitored in our study. Opioid analgesic could induce bowel dysfunction, which usually occurred immediately after the first dose and persisted within the duration of therapy. Opioid analgesic was reported as an essential indicator of PPOI[25,26]. Whether opioid analgesics were used postoperatively was also evaluated as a consequence of pain tolerance of patients on the first day after surgery.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were used to detect the relationship between variables and PPOI. In the univariate analysis, crude analyses were performed to identify potential risk factors. All variables having a bivariate association with PPOI with P < 0.1 were included in the multivariable model. A collinearity screening was performed on all independent variables to eliminate the variable with a variance inflation factor > 10. A stepwise nomogram model of PPOI was developed using a multivariate logistic regression. The nomogram model was performed following a backward step-down selection process using a threshold of P < 0.05. We can explain the nomogram by the following steps: First, determine the value of the variable on the corresponding axis; second, draw a vertical line to the total points axis to determine the points; third, add the points of each variable; and finally, draw a line from the total point axis to determine the PPOI probabilities at the lower line of the nomogram. The discriminatory ability of the model was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The accuracy of our model was further verified by bootstrap validation using computer resampling for 500 repetitions of simple random sampling with replacement. The calibration curve was employed to detect the concentricity between the model probability curve and ideal curve. The clinical usefulness of our model was evaluated using the net benefit curve, which was derived by Vickers et al[27].

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD or median (min-max value), while categorical data are expressed as number and percentage. The associations between PPOI and variables were assessed using χ2 tests, Fisher exact tests, and logistic regression models. Statistical analyses were two tailed with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, New York), R software (http://www. R-project.org), and Empower Stats software (http://www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, Boston, Massachusetts).

We retrospectively analyzed data from a prospective registry database developed and updated by the Department of General Surgery, Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. The patient, operation, tumor, and postoperative characteristics of 162 GC patients who underwent gastrectomy from June 2016 to March 2017 are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the mean age at diagnosis was 59.5 ± 10.9 years, and 124 (76.54%) patients were men. Thirty-one (19.14%) patients previously underwent abdominal surgery, while 61.11% underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy. Opioid analgesic was used for postoperative pain relief in 62 (38.27%) patients. Of 162 patients, PPOI occurred in 36 (19.75%, 95%CI: 14.1%-26.8%) patients.

| Characteristic | Category | n = 162 | Percentage (%) |

| Sex | Female | 38 | 23.46 |

| Male | 124 | 76.54 | |

| Age(yr) | Range 30-89 | — | — |

| Mean 59.5, median 59.0 | — | — | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Range 22.30-26.80 | — | — |

| Mean 24.66, median 24.95 | — | — | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | No | 131 | 80.86 |

| Yes | 31 | 19.14 | |

| Operation method | Open surgery | 63 | 38.89 |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 99 | 61.11 | |

| Operation time (min) | Range 120-433 | — | — |

| Mean 236.4, median 230.0 | — | — | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Range 10-1800 | — | — |

| Mean 229.4, median 200.0 | — | — | |

| Blood transfusion | No | 131 | 80.86 |

| Yes | 31 | 19.14 | |

| Surgical procedure | Proximal gastrectomy | 21 | 12.96 |

| Distal gastrectomy | 56 | 34.57 | |

| Total gastrectomy | 85 | 52.47 | |

| Lymph node dissection | D1+ | 40 | 24.69 |

| D2 | 122 | 75.31 | |

| Tumor stage | I | 39 | 24.07 |

| II | 50 | 30.86 | |

| III | 72 | 44.44 | |

| IV | 1 | 0.62 | |

| Postoperative body temperature (°C) | Range 36.4-39.1 | — | — |

| Mean 37.6, median 37.5 | — | — | |

| Postoperative WBC count (×109/L) | Range 5.43-22.02 | — | — |

| Mean 12.76, median 12.70 | — | — | |

| Postoperative albumin (g/L) | Range 25.5-40.3 | — | — |

| Mean 31.93, median 31.80 | — | — | |

| Postoperative K+ (mmol/L) | Range 2.67-5.15 | — | — |

| Mean 3.75, median 3.74 | — | — | |

| Postoperative opioid analgesic | No | 100 | 61.73 |

| Yes | 62 | 38.27 | |

| PPOI | No | 130 | 80.25 |

| Yes | 32 | 19.75 |

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses performed to detect the relationship between variables and PPOI. The risk of PPOI among patients aged ≤ 60 years was lower than that of patients aged > 60 years (OR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.19-0.95, P = 0.033) and the risk increased 5% for per year increase in age. Compared with the laparoscopic group, more patients in the open surgery group developed PPOI, with a significantly increased risk (OR = 2.44, 95%CI: 1.11-5.26, P = 0.025). Patients with early-stage (I and II) gastric carcinoma were less likely to suffer from PPOI than those with advanced-stage GC (III and IV), with a decreased risk of 59% (OR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.19-0.92, P = 0.027). Besides, avoiding the use of opioid analgesics during the postoperative period reduced the frequency of PPOI by 71% (OR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.13-0.64, P = 0.002). For postoperative albumin and potassium levels, there was no relationship with PPOI when considered as categorical variables; however, significant differences were found when they were regarded as continuous variable, and these results need to be further excavated in the following studies. In addition, there was no significant difference in the incidence of PPOI between the two groups in terms of sex, BMI, previous abdominal surgery, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, blood transfusion, surgical procedure, lymph node dissection, postoperative body temperature, and postoperative WBC count. All variables having a bivariate association with PPOI with P < 0.1 were included in the multivariable logistic regression, which yielded the adjusted ORs shown in Table 2. In the multivariable model, the significant predictors of PPOI were: Age older than 60 years (OR = 2.70, 95%CI: 1.10-6.66, P = 0.030), open surgery (OR = 3.45, 95%CI: 1.33-9.09, P = 0.010), advanced III-IV stage (OR = 3.23, 95%CI: 1.32-7.90, P = 0.010), and postoperative use of opioid analgesic (OR = 5.84, 95%CI: 2.25-15.16, P < 0.001). All possible two-way interactions among variables in the multivariable model were examined, but no statistically significant (P > 0.05) interaction was found.

| Variable | Category | Number (%) with PPOI | Univariate OR(95%CI) | P value | Multivariable OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Sex | Female | 9/38 (23.7) | 1.36 (0.57, 3.27) | 0.487 | — | — |

| Male | 23/124 (18.5) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Age (yr) | Continuous variable | — | 1.05 (1.01, 1.09) | 0.009 | — | — |

| ≤ 60 | 12/88 (13.6) | 0.43 (0.19, 0.95) | 0.033 | Ref. | 0.030 | |

| > 60 | 20/74 (27.0) | Ref. | — | 2.70 (1.10, 6.66) | — | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Continuous variable | — | 0.91 (0.81, 1.02) | 0.110 | — | — |

| ≤ 24.66 | 17/78 (21.8) | 1.02 (0.42, 2.49) | 0.529 | — | — | |

| > 24.66 | 15/84 (17.9) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | No | 27/131 (15.1) | 1.35 (0.47, 3.85) | 0.573 | — | — |

| Yes | 5/31 (16.1) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Operation method | Open surgery | 18/63 (20.6) | 2.44 (1.11, 5.26) | 0.025 | 3.45 (1.33, 9.09) | — |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 14/99 (14.1) | Ref. | — | Ref. | 0.010 | |

| Operation time (min) | Continuous variable | — | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.532 | — | — |

| ≤ 236.4 | 16/89 (18.0) | 0.78 (0.36, 1.69) | 0.531 | — | — | |

| > 236.4 | 16/73 (21.9) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Continuous variable | — | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.693 | — | — |

| ≤ 229.4 | 16/87 (18.4) | 1.02 (0.42, 2.49) | 0.639 | — | — | |

| > 229.4 | 8/75 (21.3) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Blood transfusion | No | 23/131 (17.6) | 0.52 (0.21, 1.28) | 0.149 | — | — |

| Yes | 9/31 (29.0) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Surgical procedure | Total gastrectomy | 21/85 (24.7) | Ref. | — | — | — |

| Proximal gastrectomy | 3/21(14.3) | 0.51 (0.14, 1.89) | 0.314 | — | — | |

| Distal gastrectomy | 8/56 (14.3) | 0.51 (0.21, 1.25) | 0.138 | — | — | |

| lymph node dissection | D1+ | 5/40 (12.5) | Ref. | — | — | — |

| D2 | 27122 (22.1) | 1.99 (0.71, 5.59) | 0.191 | — | — | |

| Tumor stage | I-II | 12/89 (13.5) | 0.41 (0.19, 0.92) | 0.027 | Ref. | 0.010 |

| III-IV | 20/73 (27.4) | Ref. | — | 3.23 (1.32, 7.90) | — | |

| Postoperative body temperature (°C) | Continuous variable | — | 0.99 (0.47, 2.05) | 0.969 | — | — |

| ≤ 37.6 | 19/97 (19.6) | 0.97 (0.44, 2.14) | 0.948 | — | — | |

| > 37.6 | 13/65 (20.0) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Postoperative WBC count (×109/L) | Continuous variable | — | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | 0.572 | — | — |

| ≤ 12.76 | 18/82 (22.0) | 1.33 (0.61, 2.89) | 0.477 | — | — | |

| > 12.76 | 14/80 (17.5) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Postoperative albumin (g/L) | Continuous variable | — | 0.83 (0.72, 0.95) | 0.007 | — | — |

| ≤ 31.93 | 21/86 (24.4) | 1.91 (0.85, 4.28) | 0.113 | — | — | |

| > 31.93 | 11/76 (14.5) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Postoperative K+ (mmol/L) | Continuous variable | — | 0.26 (0.08, 0.81) | 0.020 | — | — |

| ≤ 3.75 | 20/85 (23.5) | 1.67 (0.75, 3.69) | 0.205 | — | — | |

| > 3.75 | 12/77 (16.0) | Ref. | — | — | — | |

| Postoperative opioid analgesic | No | 12/100 (12.0) | 0.29 (0.13, 0.64) | 0.002 | Ref. | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 20/62 (32.3) | Ref. | — | 5.84 (2.25, 15.16) | — | |

| Postoperative opioid analgesic | No | 12/100 (12.0) | 0.002 | 0.29 (0.13, 0.64) | — |

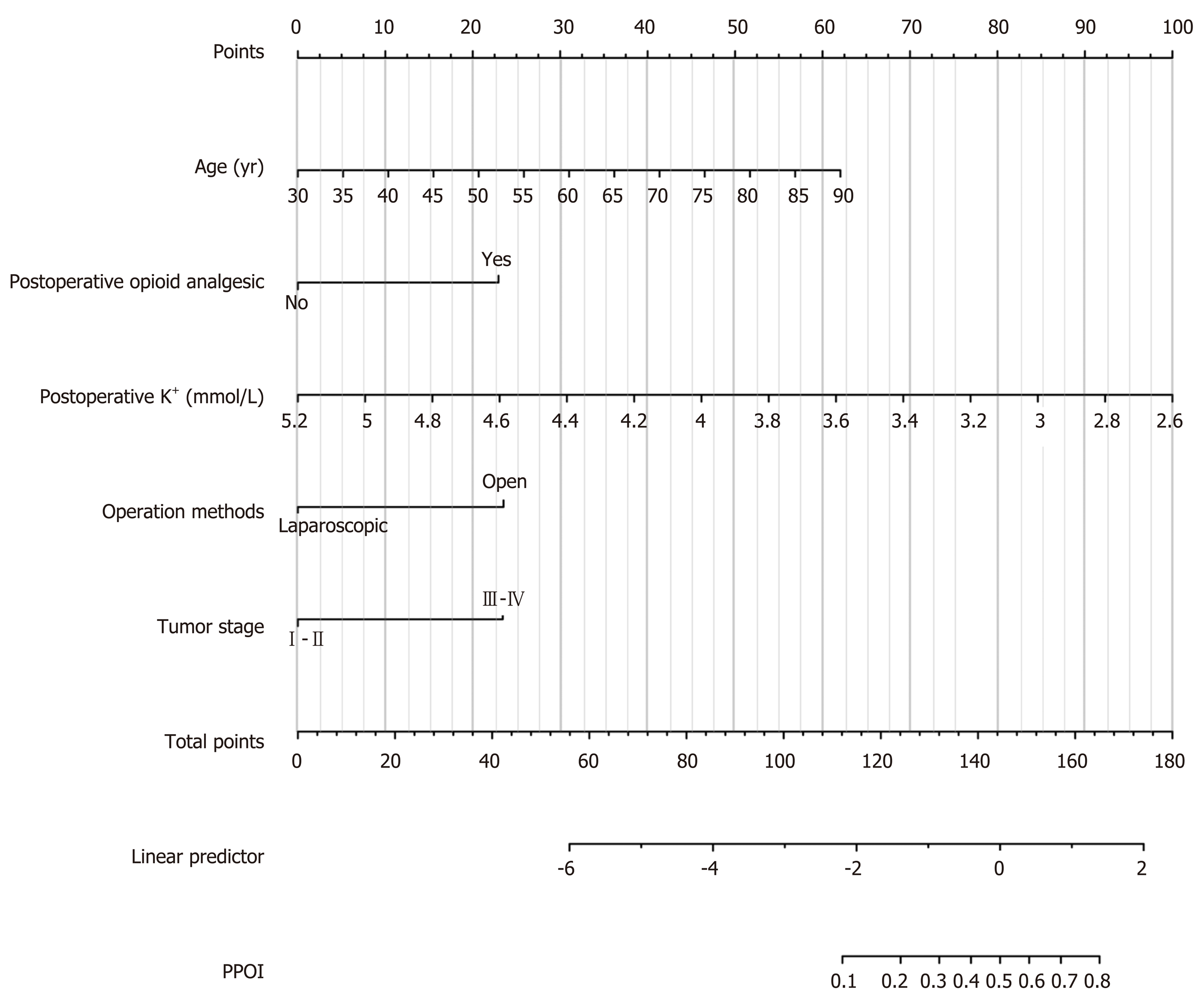

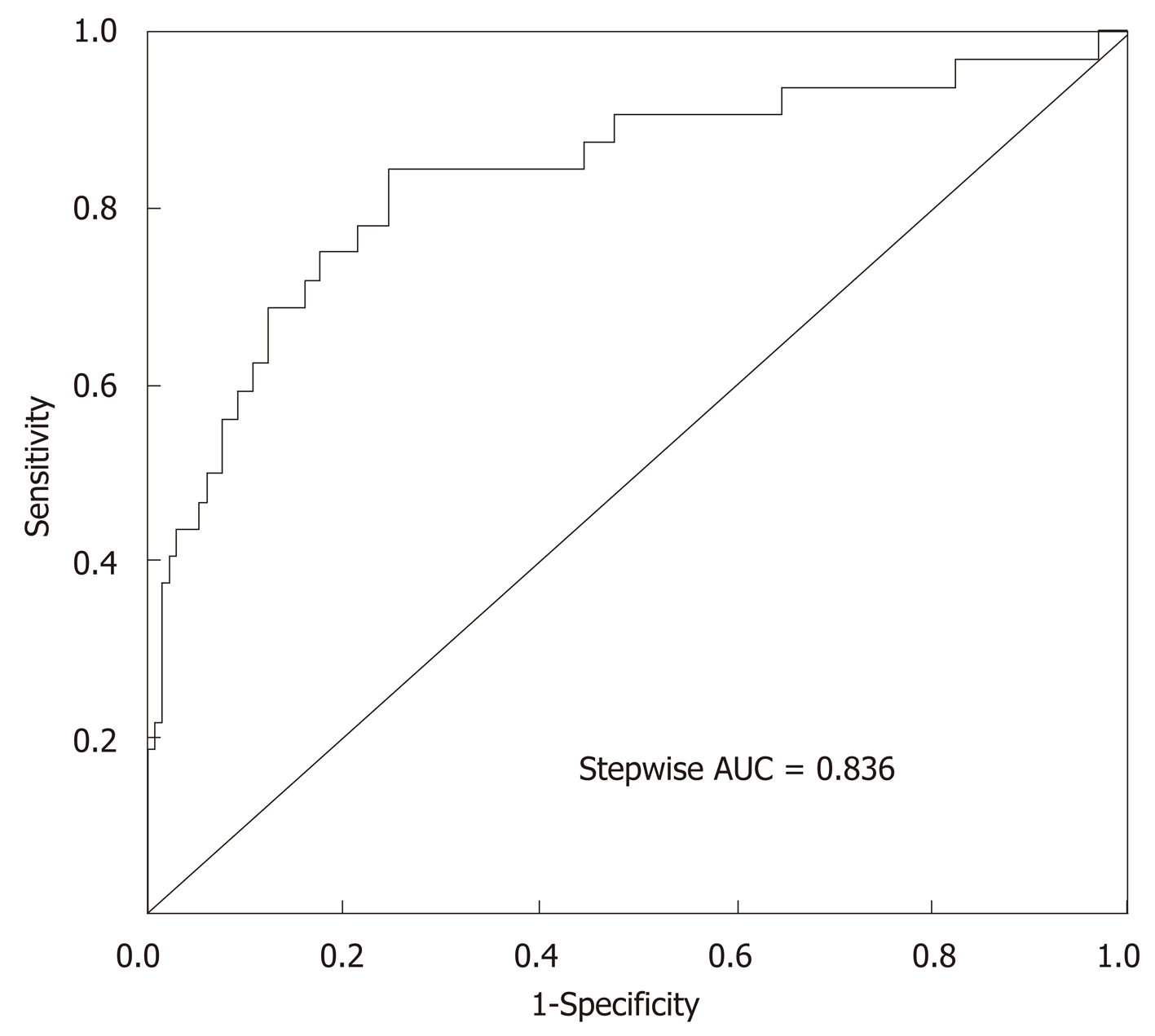

Fourteen clinicopathological variables were analyzed to determine their association with PPOI. Of the initial 14 variables, 5 were filtered out: Age, postoperative opioid analgesic, postoperative K+, operation methods, and tumor stage. In this study, the stepwise selected model was computed as follows: 3.24671 + 0.07000 × (age) + 1.55342 × (postoperative opioid analgesic = yes) - 2.60385 × (postoperative K+) - 1.59227 × (operation methods = laparoscopic surgery) + 1.58622 × (tumor stage = III-IV). The probability of PPOI can be estimated using the stepwise nomogram, as described in Figure 2. The performance of this nomogram was measured using ROC curve analysis, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) of this model was 0.836, indicating a good diagnostic performance (Figure 3) with a sensitivity of 84.4% and a specificity of 75.4% at the optimal cutoff value.

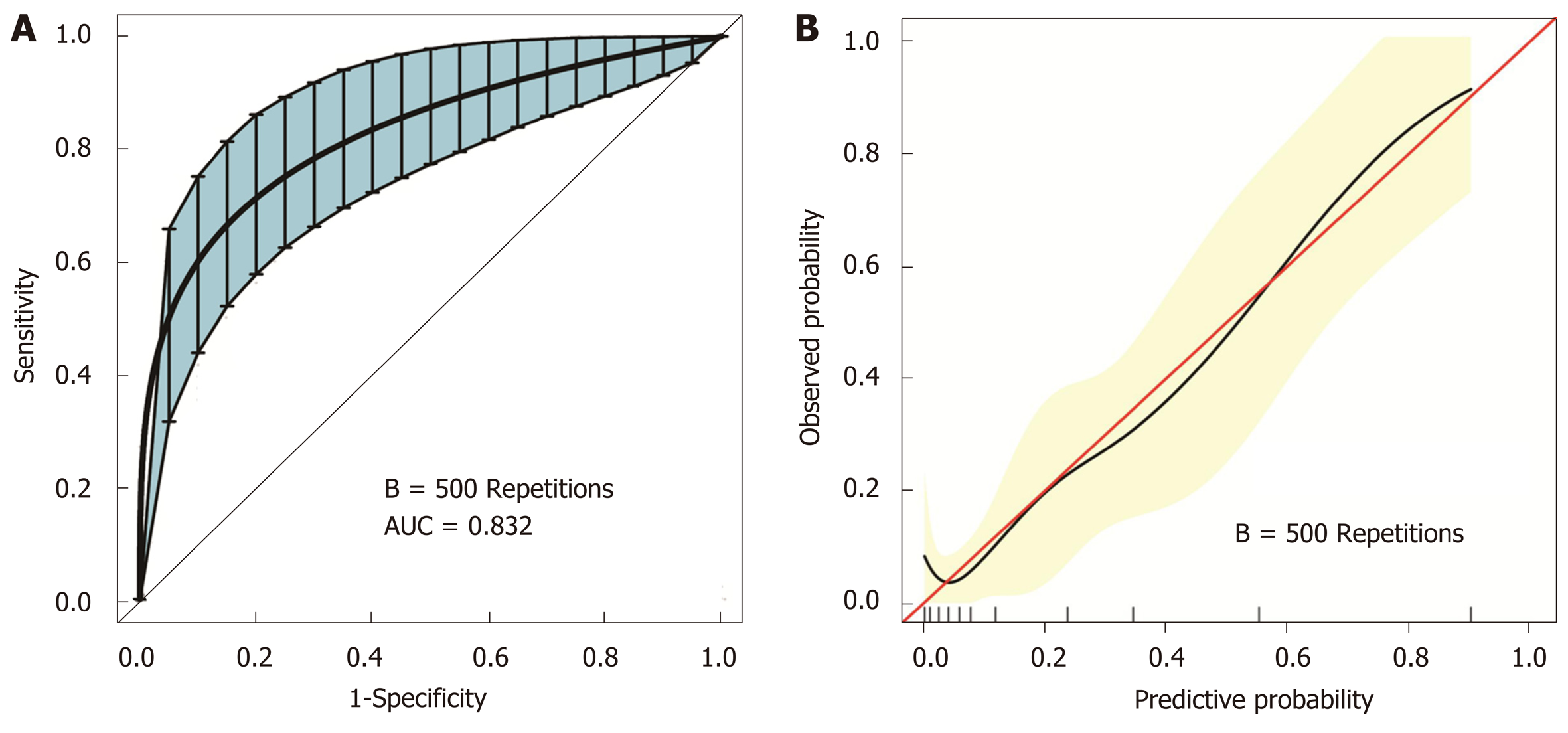

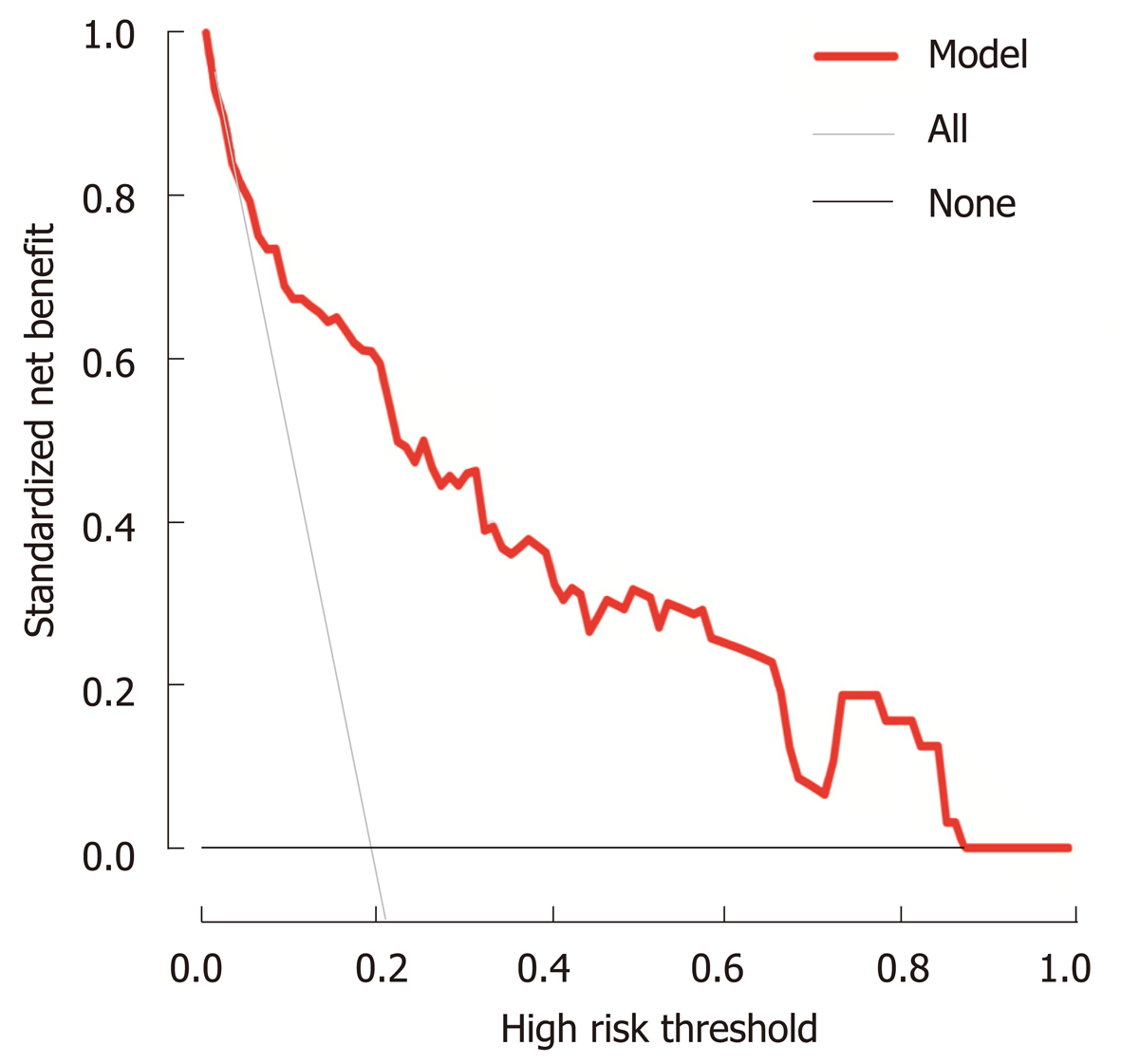

The stepwise nomogram was further validated using internal bootstrap validation. The ROC curve was measured by bootstrapping for 500 repetitions, and the AUC of the bootstrap stepwise model was 0.832 (95%CI: 0.741-0.924), with a statistical power similar to that of the initial stepwise model (Figure 4A). The internal bootstrap validation calibration curve demonstrated that at a probability of 0-0.5, the nomogram-derived curve may underestimate the risk of PPOI (Figure 4B). When the probability was higher than 0.5, the nomogram may overestimate the probability. In general, our model showed a good fitting and calibration with the ideal curve. In addition, decision curve analysis demonstrated good positive net benefits in the predictive model under a threshold probability of 0.8, indicating the favorable potential clinical effect of the predictive model (Figure 5).

This study analyzed 14 potential variables of PPOI in 162 GC patients who underwent gastrectomy. The following independent risk factors were identified: Age older than 60 years, open surgery, advanced stage (III-IV), and postoperative use of opioid analgesic. A simple and easy-to-use prediction nomogram for PPOI after gastrectomy using multivariate analyses was developed for the first time. Five variables were filtered out for the nomogram using stepwise regression. This nomogram had an excellent diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.836, sensitivity = 84.4%, and specificity = 75.4%) and was validated internally using the bootstrap sampling method. Besides, this prediction model showed superior performance when used in the clinical setting based on the results of the decision curve analysis.

Knowledge on the incidence of PPOI could make a vital contribution to the development of new strategies to prevent or decrease such incidence. A total of 36 patients were diagnosed with PPOI in the present study, accounting for 19.75% of the total patients who underwent radical gastrectomy. The frequency of PPOI in our study was lower than that in the study of Huang et al[12] (32.4%), which was conducted in patients with GC, and the study of Mao et al[28] (27%), which was conducted in patients who underwent elective colorectal surgery, and was similar to that reported in the study of Wolthuis et al[29] (15.9%), which was conducted in patients after colorectal resection. A meta-analysis of 54 studies revealed a PPOI incidence of 10.3% after colorectal surgery[19]. Notably, the frequency of PPOI varied in the previous studies, depending on the type of abdominal surgery and definitions of PPOI. There is no widely accepted precise cutoff time over which ileus should persist before being regarded as prolonged, which varied from 3 d to 7 d in different studies[8,22,30]. A standardized and universally accepted definition of the exact point in time when normal POI changes to PPOI should be identified in future research. In the present study, advanced age (> 60 years) was identified as an independent predictor of PPOI. This finding is in line with those of several previous studies[12,31], which indicated that physicians should pay more attention to those patients. Older patients usually have reduced peristalsis and need more time for postoperative recovery[32]. Low albumin has been identified as an independent risk factor for the development of PPOI[6] and older patients generally have a poor nutritional and functional status. Our study emphasizes the need for perioperative dietary intervention in older patients who underwent gastrectomy for advanced GC.

We identified the laparoscopic approach as a way to limit PPOI, and this finding is consistent with the results reported in other studies[29-31]. The long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy for patients with GC were comparable to those of open gastrectomy in a large-scale, multicenter, retrospective clinical study conducted in 2976 patients[33]. With the development of minimally invasive techniques, experienced surgeons can safely perform laparoscopic gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced GC[34]. The gastrointestinal function of patients who underwent open abdominal surgery took 2 d to recover compared with that of patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery[6]. Laparoscopy is recommended as a feasible and reproducible procedure in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with GC, which results in decreased PPOI, faster recovery, and definite clinical effect.

Opioid-related dysmotility is thought to play a central role in postoperative gut dysfunction, and the effect of opioid analgesic on gastrointestinal function has been well elucidated in previous studies[25,26]. Opioid analgesic was also identified as an independent risk factor for PPOI in the present study. Opioid analgesic usually activates peripheral μ-opioid receptors located in the myenteric plexus, further inhibits acetylcholine, and impairs the gut motility[35]. Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists methylnaltrexone and alvimopan, which are potentially used for the prevention of PPOI, are a new class of drugs designed to reverse opioid-induced side effects on the gastrointestinal system without compromising pain relief[25,36,37].

The nomogram was used to calculate the overall probability of PPOI for an individual patient in the present study. This prediction model is important for risk estimation, improving the communication between patients and physicians, and clinical decision-making. In the present study, five independent variables were filtered out using stepwise regression, and the nomogram was established to predict the risk of PPOI in GC patients. The nomogram showed an excellent diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.836) and yielded a sensitivity of 84.4% and specificity of 75.4% at the optimal cutoff value. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate a nomogram for predicting PPOI in GC patients. The nomogram might serve as a statistical tool to calculate the overall probability of PPOI in patients who underwent gastrectomy. This novel nomogram might serve as an essential early warning sign of PPOI in gastric cancer patients. If patients are associated with higher risk estimates, doctors and nurses may take appropriate measures including postoperative management and adjustments in pharmacological treatment.

The present study has some strengths. First, the majority of the previous studies focused on investigating the incidence of PPOI in patients with colonic or rectal cancer, and only a few studies were conducted among GC patients. This study provided novel evidence of PPOI in GC. Second, a nomogram prediction model of PPOI was first established for GC patients, which had great potential value for the clinical recommendation. Besides, the nomogram was confirmed to be constant by internal bootstrap validation and was found to have good positive net benefits by decision curve analysis. By contrast, the present study has several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study and the relatively small sample size may have weakened the results of the analyses. Second, the nomogram lacked a robust external validation. Therefore, these results need further validation in the subsequent studies.

In conclusion, PPOI is one of the common complications in GC patients who underwent gastrectomy. Age, postoperative opioid analgesic, operation methods, and tumor stage are independent risk factors for PPOI. Less traumatic operative technique and avoidance of postoperative pain medications are encouraged for GC patients. This study has established an easy-to-use nomogram model for predicting PPOI in GC patients. The novel nomogram might serve as an essential early warning sign to help doctors and nurses take appropriate measures.

Prolonged postoperative ileus (PPOI) is one of the common complications in gastric cancer patients who underwent gastrectomy. PPOI is an essential contributor to cause the increase of hospitalization expense and extension of hospitalization time.

For the research of PPOI, most of previous studies were focused on colorectal cancer. Evidence in gastric cancer is scanty and needs further study.

This study aimed to evaluate the risk factors for PPOI after gastrectomy in gastric cancer and put forward a prediction model for clinical practitioners.

In this retrospective study, we performed univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses to detect the relationship between variables and PPOI. We established a nomogram model for PPOI following a backward step-down selection process.

The incidence of PPOI was 19.75% in patients with gastrectomy. Age, postoperative opioid analgesic, surgical methods, and tumor stage were independent risk factors of PPOI. A nomogram was established and had a good performance. The nomogram was further validated using internal bootstrap validation, and the decision curve analysis demonstrated good positive net benefits of this model.

The novel nomogram might serve as an essential early warning sign of PPOI in gastric cancer patients and thus will help doctors and nurses take appropriate measures.

Further studies are needed to validate this predictive nomogram model, and some basic medical studies are meaningful to investigate the mechanism of PPOI.

We are very grateful to Wan-Guo Xue, PhD (Gastric Cancer Specialized Disease Database Construction Project of National Engineering Laboratory, Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Hospital), Hui Luo, PhD (Gastric Cancer Specialized Disease Database Construction Project of National Engineering Laboratory, Chinese PLA General Hospital), Chi Chen and Xing-Lin Chen of Yi-er College for their help in statistical analysis.

| 1. | van Bree SH, Nemethova A, Cailotto C, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Matteoli G, Boeckxstaens GE. New therapeutic strategies for postoperative ileus. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:675-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pavoor R, Milsom J. Postoperative ileus after laparoscopic colectomy: elusive and expensive. Ann Surg. 2011;254:1075; author reply 1075-1075; author reply 1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fesharakizadeh M, Taheri D, Dolatkhah S, Wexner SD. Postoperative ileus in colorectal surgery: is there any difference between laparoscopic and open surgery? Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mowat AM. Janus-like monocytes regulate postoperative ileus. Gut. 2017;66:2049-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Bree SH, Bemelman WA, Hollmann MW, Zwinderman AH, Matteoli G, El Temna S, The FO, Vlug MS, Bennink RJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Identification of clinical outcome measures for recovery of gastrointestinal motility in postoperative ileus. Ann Surg. 2014;259:708-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vather R, Josephson R, Jaung R, Robertson J, Bissett I. Development of a risk stratification system for the occurrence of prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery: a prospective risk factor analysis. Surgery. 2015;157:764-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vather R, Trivedi S, Bissett I. Defining postoperative ileus: results of a systematic review and global survey. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:962-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Chapuis PH, Bokey L, Keshava A, Rickard MJ, Stewart P, Young CJ, Dent OF. Risk factors for prolonged ileus after resection of colorectal cancer: an observational study of 2400 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:909-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Juárez-Parra MA, Carmona-Cantú J, González-Cano JR, Arana-Garza S, Treviño-Frutos RJ. Risk factors associated with prolonged postoperative ileus after elective colon resection. Revista de Gastroenterología de México (English Edition). 2015;80:260-266. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Iyer S, Saunders WB, Stemkowski S. Economic burden of postoperative ileus associated with colectomy in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:485-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan DC, Liu YC, Chen CJ, Yu JC, Chu HC, Chen FC, Chen TW, Hsieh HF, Chang TM, Shen KL. Preventing prolonged post-operative ileus in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy and intra-peritoneal chemotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4776-4781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang DD, Zhuang CL, Wang SL, Pang WY, Lou N, Zhou CJ, Chen FF, Shen X, Yu Z. Prediction of Prolonged Postoperative Ileus After Radical Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: A Scoring System Obtained From a Prospective Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56652] [Article Influence: 7081.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (134)] |

| 14. | Li L, Ding J, Han J, Wu H. A nomogram prediction of postoperative surgical site infections in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang H, Li W, Zhang L, Yan X, Shi D, Meng H. A nomogram prediction of peri-implantitis in treated severe periodontitis patients: A 1-5-year prospective cohort study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20:962-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim SY, Yoon MJ, Park YI, Kim MJ, Nam BH, Park SR. Nomograms predicting survival of patients with unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer who receive combination cytotoxic chemotherapy as first-line treatment. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:453-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kehlet H, Holte K. Review of postoperative ileus. Am J Surg. 2001;182:3S-10S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wehner S, Vilz TO, Stoffels B, Kalff JC. Immune mediators of postoperative ileus. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:591-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wolthuis AM, Bislenghi G, Fieuws S, de Buck van Overstraeten A, Boeckxstaens G, D'Hoore A. Incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O1-O9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shi Y, Zhang XP, Qin H, Yu YJ. Naso-intestinal tube is more effective in treating postoperative ileus than naso-gastric tube in elderly colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:1047-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1911] [Article Influence: 127.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dai X, Ge X, Yang J, Zhang T, Xie T, Gao W, Gong J, Zhu W. Increased incidence of prolonged ileus after colectomy for inflammatory bowel diseases under ERAS protocol: a cohort analysis. J Surg Res. 2017;212:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vather R, Josephson R, Jaung R, Kahokehr A, Sammour T, Bissett I. Gastrografin in Prolonged Postoperative Ileus: A Double-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2015;262:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kuruba R, Fayard N, Snyder D. Epidural analgesia and laparoscopic technique do not reduce incidence of prolonged ileus in elective colon resections. Am J Surg. 2012;204:613-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Becker G, Blum HE. Novel opioid antagonists for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction and postoperative ileus. The Lancet. 2009;373:1198-1206. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Koo KC, Yoon YE, Chung BH, Hong SJ, Rha KH. Analgesic opioid dose is an important indicator of postoperative ileus following radical cystectomy with ileal conduit: experience in the robotic surgery era. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:1359-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3515] [Cited by in RCA: 3830] [Article Influence: 191.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Mao H, Milne TGE, O'Grady G, Vather R, Edlin R, Bissett I. Prolonged Postoperative Ileus Significantly Increases the Cost of Inpatient Stay for Patients Undergoing Elective Colorectal Surgery: Results of a Multivariate Analysis of Prospective Data at a Single Institution. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:631-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wolthuis AM, Bislenghi G, Lambrecht M, Fieuws S, de Buck van Overstraeten A, Boeckxstaens G, D'Hoore A. Preoperative risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:883-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Hwang GS, Hanna MH, Phelan M, Carmichael JC, Mills S, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ. Risk factors for prolonged ileus following colon surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:603-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hain E, Maggiori L, Mongin C, Prost A la Denise J, Panis Y. Risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus after laparoscopic sphincter-saving total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: an analysis of 428 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:337-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Masoomi H, Kang CY, Chaudhry O, Pigazzi A, Mills S, Carmichael JC, Stamos MJ. Predictive factors of early bowel obstruction in colon and rectal surgery: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2006-2008. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Kim W, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Song KY, Ryu SY. Long-term results of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large-scale case-control and case-matched Korean multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:627-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, Xue Y, Suo J, Tao K, He X, Wei H, Ying M, Hu W, Du X, Chen P, Liu H, Zheng C, Liu F, Yu J, Li Z, Zhao G, Chen X, Wang K, Li P, Xing J, Li G. Morbidity and Mortality of Laparoscopic Versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1350-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vather R, O'Grady G, Bissett IP, Dinning PG. Postoperative ileus: mechanisms and future directions for research. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41:358-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nair A. Alvimopan for post-operative ileus: What we should know? Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2016;54:97-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Xu LL, Zhou XQ, Yi PS, Zhang M, Li J, Xu MQ. Alvimopan combined with enhanced recovery strategy for managing postoperative ileus after open abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2016;203:211-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected byan in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P-Reviewer: Amiri M, Fiori E, Kim GH, Sterpetti AV S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhang YL