Published online Jan 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i3.388

Peer-review started: November 12, 2018

First decision: December 5, 2018

Revised: January 8, 2019

Accepted: January 14, 2019

Article in press: January 14, 2019

Published online: January 21, 2019

Processing time: 73 Days and 20.4 Hours

The clinical presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) shows a large symptom variation also in different intensities among patients. As several studies have shown, there is a large overlap in the symptomatic spectrum between proven GERD and other disorders such as dyspepsia, functional heartburn and/or somatoform disorders.

To prospectively evaluate the GERD patients with and without somatoform disorders before and after laparoscopic antireflux surgery.

In a tertiary referral center for foregut surgery over a period of 3 years patients with GERD, qualifying for the indication of laparoscopic antireflux surgery, were investigated prospectively regarding their symptomatic spectrum in order to identify GERD and associated somatoform disorders. Assessment of symptoms was performed by an instrument for the evaluation of somatoform disorders [Somatoform Symptom Index (SSI) > 17]. Quality of life was evaluated by Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI).

In 123 patients an indication for laparoscopic antireflux surgery was established and in 43 patients further medical therapy was suggested. The portion of somatoform tendencies in the total patient population was 20.48% (34 patients). Patients with a positive SSI had a preoperative GIQLI of 77 (32-111). Patients with a normal SSI had a GIQLI of 105 (29-140) (P < 0.0001). In patients with GERD the quality of life could be normalized from preoperative reduced values of GIQLI 102 (47-140) to postoperative values of 117 (44-144). In patients with GERD and somatoform disorders, the GIQLI was improved from preoperative GIQLI 75 (47-111) to postoperative 95 (44-122) (P < 0.0043).

Patients with GERD and associated somatoform disorders have significantly worse levels of quality of life. The latter patients can also benefit from laparoscopic fundoplication, however they will not reach a normal level.

Core tip: The current level of evidence performing antireflux surgery in patients with overlapping symptoms such as dyspepsia, functional heartburn and/or somatoform disorders is limited and debated in small case series. In a tertiary referral center for foregut surgery (the largest center for antireflux surgery in Germany), we studied patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) regarding their symptomatic spectrum over a period of 3 years. It was found that patients with GERD and associated somatoform disorders have significantly worse levels of quality of life. The latter patients can also benefit from laparoscopic fundoplication, however they will not reach a normal level.

- Citation: Fuchs HF, Babic B, Fuchs KH, Breithaupt W, Varga G, Musial F. Do patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and somatoform tendencies benefit from antireflux surgery? World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(3): 388-397

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i3/388.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i3.388

The clinical presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) shows a large variety of symptoms also in different intensities among patients[1-3]. As several studies have shown, there is a large overlap in the symptomatic spectrum between proven GERD and other disorders such as dyspepsia, functional heartburn and/or somatoform disorders[4-10]. This makes a precise diagnosis, just based on symptoms quite unreliable for severe therapeutic decision making such as antireflux surgery[11]. GERD can be diagnosed rather easily in patients by the presence of esophagitis during upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and/or evidence of pathologic gastroesophageal reflux in 24h-impedance-pH-monitoring, favourably optimised by a positive symptom-reflux correlation as expressed by the symptom association probability (SAP > 95% significant)[3,12].

Symptom-overlapping disorders such as somatisation or a somatoform tendency can be detected in a patient, if a given person suffers from an excessive number of somatic complaints, which cannot be explained by pathophysiologic and/or measurable findings[13]. A symptomatic screening test by Rief et al[13-15] can be used to identify those patients with somatoform disorders among those with proven GERD. Recently we have shown that GERD patients do have an overlap with somatoform tendencies in about 20% of patients of an investigated population in a tertiary referral center[10]. A similar portion (20%) of patients with somatoform tendencies can be detected in a population with foregut symptoms[16].

In GERD reliable decision making in long-term therapeutic strategies focuses on the reduction of troublesome symptoms and a dependable improvement of quality of life for the patients after treatment. The majority of GERD patients can be treated by conservative medical therapy such as protonpump inhibitors (PPI), while surgical therapy should be reserved for patients with severe and progressive disease, such as patients with anatomical and functional defects, substantial mucosal damage and/or increasingly reduced quality of life[12,17-20]. The results of antireflux surgery are well known and a good outcome ranges around 85%-90% in patients with proven GERD[12]. However, little is known about the success of antireflux surgery in patients with an overlapping problem of somatoform symptoms. The question emerges, whether it is justified to operate these patients with a combined problem of proven GERD and somatoform tendencies and if patients with a combination of GERD and somatoform problems would benefit from surgical therapy.

There are many reports on the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in GERD patients, but only few reports focusing on patients with associated and overlapping disorders such as depression or somatoform tendencies[12,17-20]. Especially data are lacking on pre- and postoperative quality of life in patients with GERD and combined somatoform disorders. As a consequence we performed a prospective evaluation of patients with GERD with and without a combination of somatoform disorders before and after laparoscopic antireflux surgery regarding their outcome.

In a tertiary referral center for foregut surgery over a period of 3 years patients with GERD, qualifying for the indication of laparoscopic antireflux surgery, were investigated prospectively regarding their symptomatic spectrum in order to identify GERD and associated somatoform disorders. Patients, fulfilling the criteria for the indication for laparoscopic antireflux surgery, entered the protocol and were followed pre-, intra- and postoperatively. This allowed for the analysis of outcome parameters between patients with GERD with and without a combined problem of somatoform tendencies.

All patients with foregut symptoms such as heartburn who were suspicious for GERD and referred to our specialized referral center for GI functional disease over a time frame of 3 years were asked for their permission and registered in this present study after Institutional Review Board approval. This was followed by a prospective protocol of investigations, assessments and therapy as well as follow up assessments. Patients fulfilling the indication criteria based on the guidelines were informed and an indication for laparoscopic antireflux surgery was established. In patients with minor and /or non-progressive disease, a continuation of PPI-therapy was suggested.

Standardized questionnaires were used to assess all presenting symptoms, and all patients underwent a validated screening test to assess somatoform disorders and quality of life[10,15,21]. Medical history, physical exams, upper GI endoscopy, GI function testing (esophageal manometry and 24 h-pH-monitoring) were performed in order to determine the presence and severity of GERD. The severity of esophagitis was graded according to the classification of Savary-Miller or the Los Angeles Classification and the vertical extension of a hiatal hernia was recorded. Water perfusion esophageal manometry, later High Resolution Manometry was performed. Position, length, and pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter were determined with the pull-through manometry. pH-monitoring or later Impedance-pH-monitoring were performed using the DeMeester-reflux-score[1]. A a value of 14.7 was used as the borderline. Medication affecting motility and acid suppression was stopped one week prior to testing.

A symptom evaluation to identify somatoform disorders was performed according to Rief et al[13-15]. As a marker for the high probability for the presence of a somatoform tendency or disorder the somatoform symptom index (SSI) was used, as recently described[10]. The SSI is positive for the presence of a somatoform tendency, if a given patient has more than 17 different symptoms, of which no explanation or cause can be detected.

Quality of life was evaluated in this study population by the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), which is a well established instrument and validated in several languages[21]. The GIQLI carries 5 different components or dimensions of quality of life such as GI-symptoms, emotional factors, physical factors, social factors and influences by the administered therapy with a maximum index point of 144, evaluated by 36 questions.

Therapeutic decision making, especially the indication for laparoscopic antireflux surgery was based on the current guidelines[12]. Patients with progressive and advanced disease, usually with evidence of past or present esophagitis, hiatal hernia, incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, pathologic esophageal acid exposure and/or good PPI response, preferably a PPI dosage increase over the past years as well as a reduction in quality of Life were selected for surgical therapy. Patients with lacking positive criteria were suggested to continue their conservative medical therapy and change of life style.

Patients with indication for surgery had to sign an informed consent prior to surgery. Standard laparoscopic antireflux procedure was a short floppy Nissen fundoplication and a posterior hiatoplasty. In patients with severe esophageal motility disorder usually with less than 50% of effective esophageal peristalsis left, received a laparoscopic partial posterior Toupet hemifundoplication, also combined with a posterior hiatoplasty and gastropexy.

The standard procedure was started with the insertion of a Verres-needle to create a capnoperitoneum and after safety tests to access the abdominal cavity with a 10 mm camera port. Additional 4 trocars were placed and the procedure was started with a limited mobilisation of cranial gastric fundus especially the posterior part to create a floppy mobile fundus with a posterior and an anterior fundic flap. In addition the hiatus was dissected and subsequently the distal esophagus was mobilized in order to gain a tension free esophageal segment of about 3cm of lower esophageal sphincter within the abdominal cavity below the hiatal arch. Then the obligatory posterior hiatal narrowing with 1-3 “figure-of-8” stitches were performed to adapt the narrowing according to the diameter of the esophagus. Afterwards the Nissen fundoplication was shaped around the esophageal sphincter, calibrated by a 18 mm bougie, and sutured including the esophageal wall. Care was taken to shape the wrap symmetrically regarding the posterior and anterior fundic flap, fixing it to the right lateral wall of the distal esophagus. Care was also taken to identify both vagal truncs and avoid damage.

Postoperatively the patients followed some dietary restrictions starting with fluid postop day 1 and 2, and increasing to semisolid on day 3, followed by their dismissal with the suggestion of several small meal rather than one main meal for 4-8 wk and refrain from hard physical work for 8 wk. Postoperative follow-up consisted of questionaires after 12 mo and a suggestion for endoscopic and functional investigations. The same instruments were used as prior to surgery. Patients were separately followed and analysed depending on their choice of therapy. As a consequence, 2 groups were established: Group A post-surgical therapy; Group B: Surgery suggested, medical therapy performed.

All data were recorded and stored in an Excel file for later comparison. The results of the different groups were compared using the non-parametric test for paired samples with Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test and the t-test for paired samples. For comparison of quality-of-life data the Wilcoxon Two Sample test was used, since the samples had different sizes.

A total of 166 patients with foregut symptoms and heartburn were prospectively included in this study over 3 years. Mean age was 58 years (20-82) and there were 82 females. In 123 patients an indication for laparoscopic antireflux surgery was established and in 43 patients further medical therapy was suggested, based on the indication criteria of the EAES guidelines. Almost a third of the patients had some kind of concomitant disease and some risk factors. The duration since the onset of the symptoms was median 5 years (1-50). The most frequent chief complaint was heartburn (61%), followed by regurgitation (18%) and epigastric pain (15%). The previous response to medication was very limited in the recent months, which led to the referral of the patients to surgery. Esophagitis was visible on endoscopy in 51% of the patients. Hiatal hernia was documented in 78%. Esophageal manometry showed in 86% an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter and in 16% an ineffective motility of the esophageal body. A pathologic esophageal acid exposure was documented in 88% of the patients.

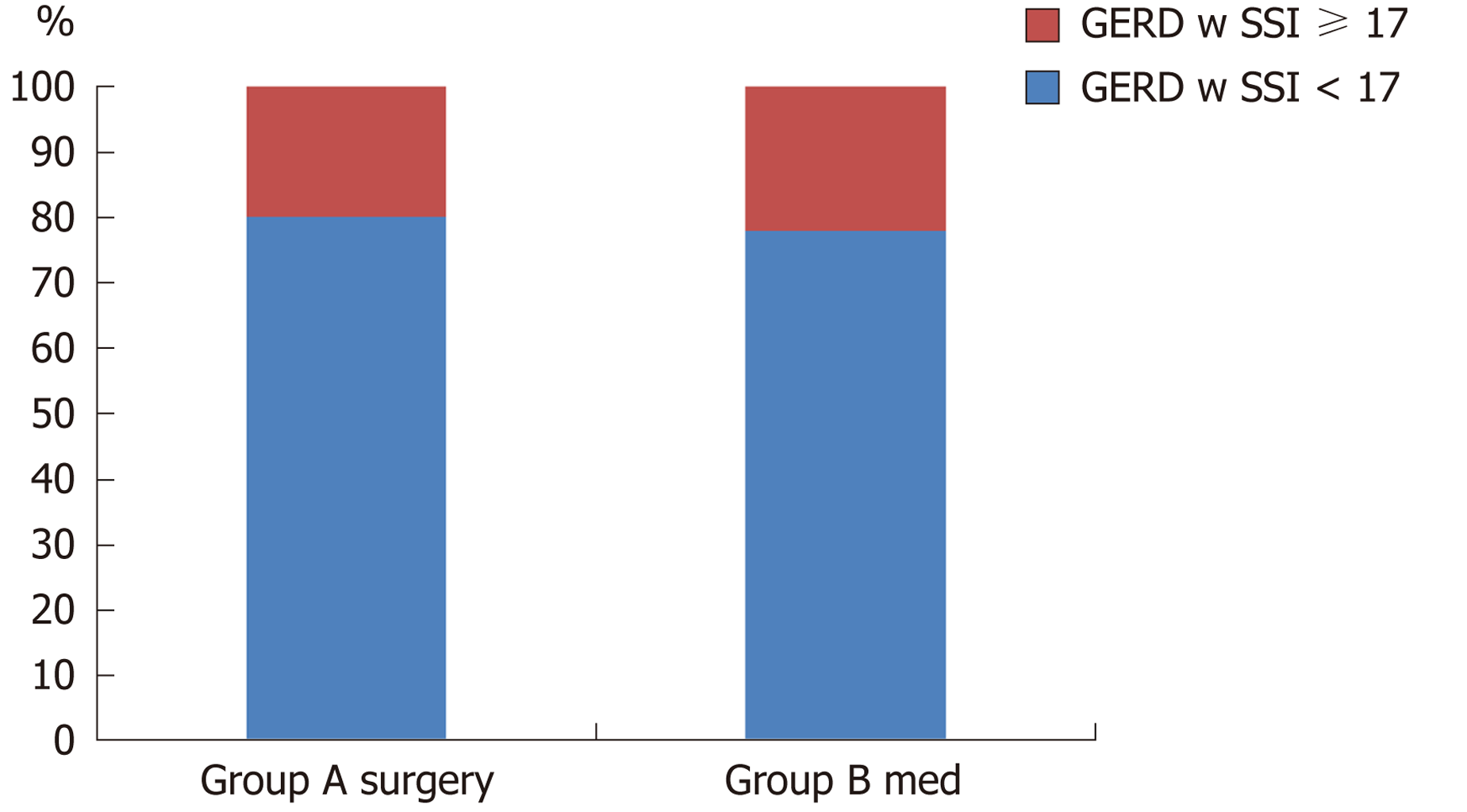

After information about the disease and the operative procedure, finally 93 patients (Group A) agreed to undergo a laparoscopic antireflux procedure. Thirty patients decided to continue medical therapy despite the fact that an indication for laparoscopic antireflux surgery was suggested (Group B). The portion of somatoform tendencies in the total patient population was 20.48% (34 patients), when the SSI ≥ 17 symptoms was used as criterion for the presence of somatoform disorders. In Group A (patients with laparoscopic fundoplication) 22% (20 patients) showed a positive SSI for somatoform tendencies, while in Group B this portion was quite similar with 20% (6 patients) (Figure 1).

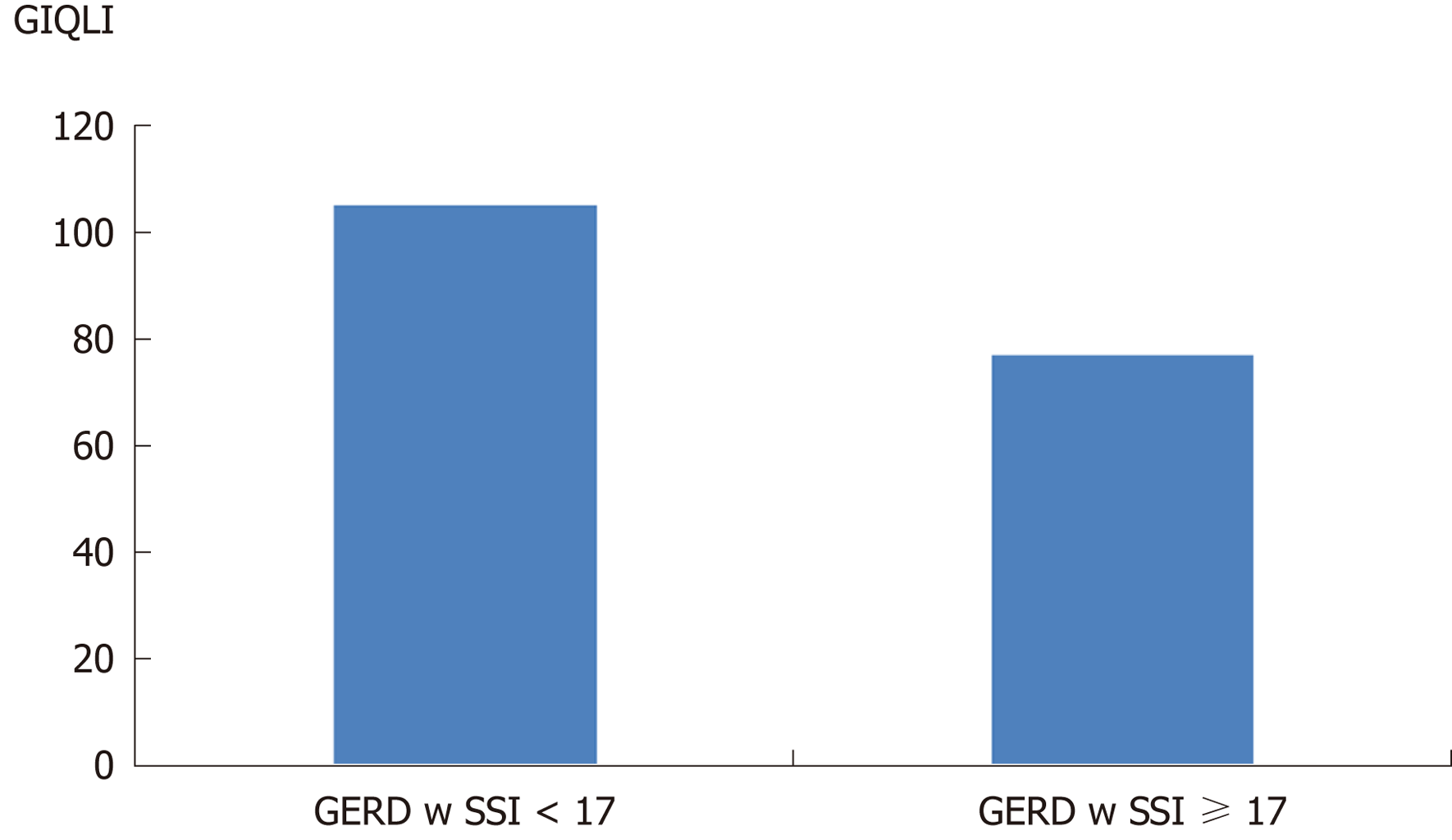

Figure 2 shows the preoperative level of the GIQLI in patients with and without a somatoform disorder as measured by the SSI (normal < 17 symptoms). Patients with a positive SSI (number of present symptoms ≥ 17) had a preoperative GIQLI of 77 (32-111). Patients with a normal SSI (< 17 symptoms) had a GIQLI of 105 (29-140). This difference was highly significant (P < 0.0001).

In all surgical cases the primary laparoscopic procedure could be performed without conversion. In four patients intraoperative opening of the pleural cavity on the left side occurred during mobilisation of the esophagus in the mediastinum, resulting in a compression of the lung by gas-insufflation. Two patients showed postoperative minor complications such as 1 patient with an extraordinary pain level, which needed 3 d of extra hospitalisation as well as 1 patient with abdominal distension and pain due to postoperative delayed intestinal motility recovery, which also needed prolonged hospital stay. All patients had dysphagia in the first 4 postoperative days during their hospitalisation and a stepwise increase in fluid, semisolid and finally solid food was given during this period in order to prevent excessive gagging and vomiting, which could cause early migration.

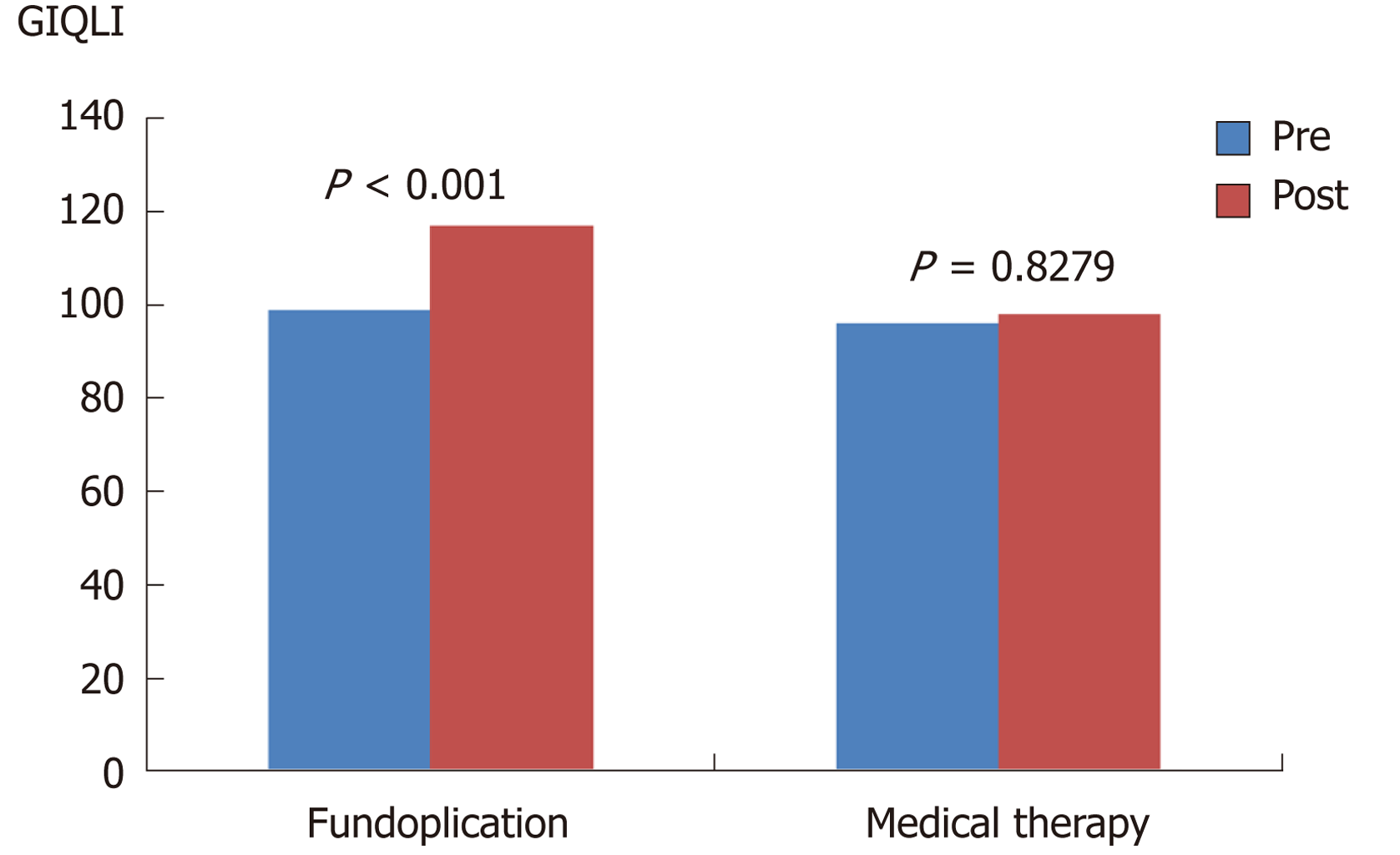

After minimum of 1 year follow-up time all patients were contacted and questionnaires were returned from 138 out of 166 patients, that were initially investigated. From the initially 93 patients with laparoscopic fundoplication, 77 patients responded and follow-up information could be obtained. Twenty-five out of 30 patients responded, who had been suggested for surgery, but decided to continue conservative treatment. Preoperative and postoperative quality of life as assessed by the GIQLI showed a significant difference (P < 0.001) for patients in Group A, operated upon with laparoscopic antireflux procedure (Figure 3).

The GIQLI of the operated patients, who responded to the follow-up, was elevated from a preoperative level of 99 (47-140) up to postoperative 117 (44-144) (P < 0.001). The normal level of GIQLI of healthy individuals is reported from 120 to 131. Patients with GERD, who decided to continue with conservative medical therapy despite the suggestion for laparoscopic surgery (group B), show after the follow-up time of at least 1 year a constant level of reduced quality of life with GIQLI of 98 (51-130; P = 0.8279; Figure 3). Within group B quality of life in those patients without somatoform tendency (SSI < 17) had an initial GIQLI of 102, which was documented at 1 year follow-up at 104 (not significant). Patients with a SSI > 17 had an initial GIQLI of 73, which was 1 year later at 72. Thus medical therapy did not change the level of Quality of life in this cohort.

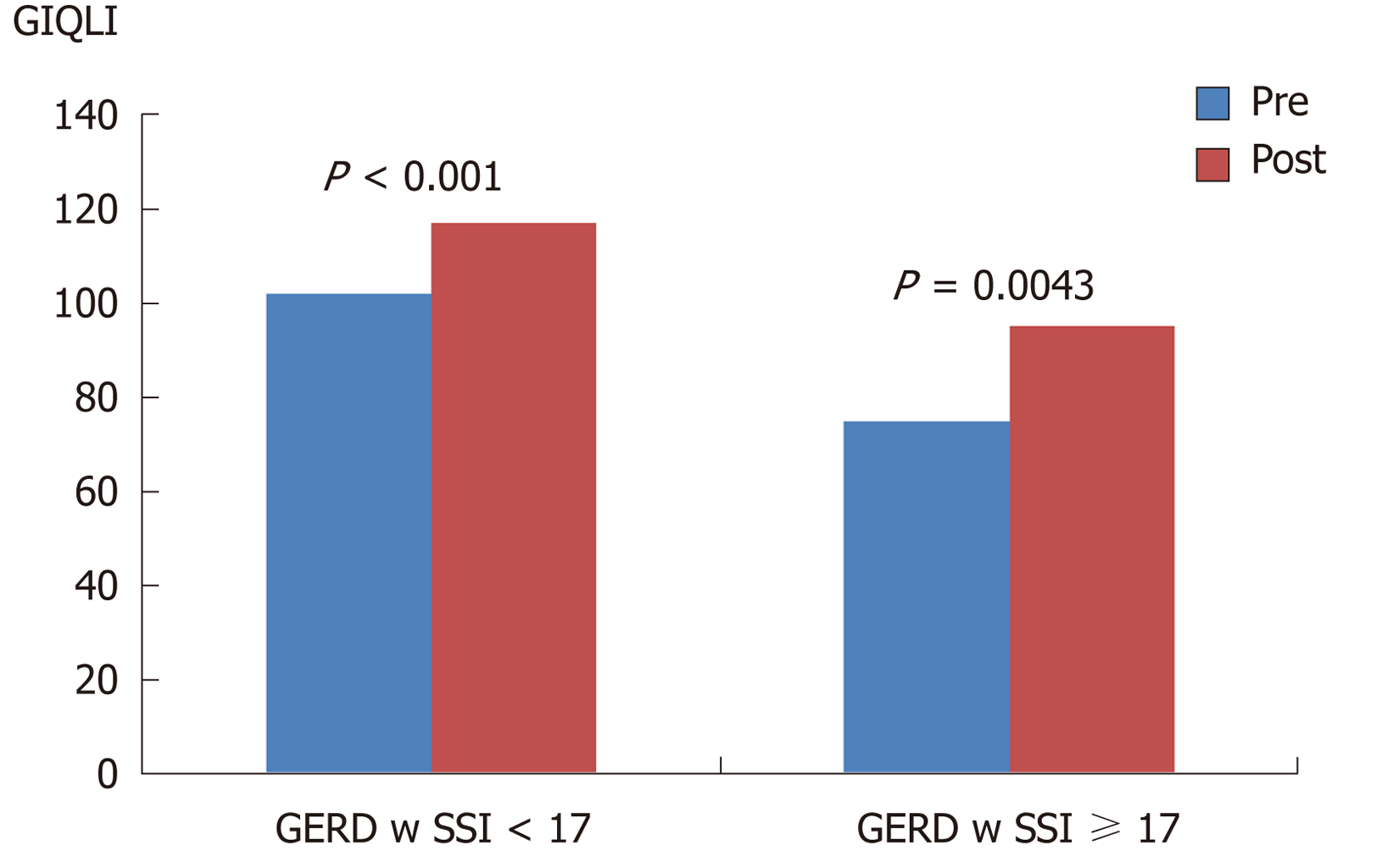

Figure 4 demonstrates the main finding of the study, comparing the pre- and postoperative level of the GIQLI, related to the presence of a somatoform disorder. In both groups, patients with GERD alone and patients with GERD and combined somatoform disorder, the quality of life could be significantly increased by the laparoscopic antireflux procedure. In the operated patients with GERD alone, Quality of Life could be normalized from preoperative reduced values of GIQLI 102 (47-140) to postoperative values of 117 (44-144). In patients with GERD and combined somatoform disorders, the GIQLI was improved from preoperative GIQLI 75 (47-111) to postoperative 95 (44-122) (P < 0.0043).

In summary, quality of life in patients with GERD as selected for surgery using the criteria as published in the guidelines is severely reduced and can be elevated by laparoscopic fundoplication to normal levels. Patients with GERD and associated somatoform disorders have significantly worse levels of quality of life. The latter patients can also benefit from laparoscopic fundoplication, however they will not reach a normal level due to the large amount of present symptoms, which can not all be influenced by antireflux surgery.

It has been shown that the classic clinical presentation of the GERD has a remarkable symptom overlap with other often functional disorders such as heartburn, somatization and/or hypertensive esophagus and others[3-10]. Several instruments have been used in the past to assess the presence of such conditions in order to verify the precise diagnosis and document the combination of GERD with somatoform tendencies[4-10,13-15]. Recently the relationship between GERD and somatoform disorders was published demonstrating a 20% incidence of combined somatoform tendencies in a population of GERD patients with more than 17 symptoms present[10]. This confirms early reports of similar involvement of patients with both conditions[16]. Two questions emerge whether a patient with somatoform disorder can be detected within a population of GERD-patients and secondly, if these patients should be selected for antireflux surgery.

Somatization represents a situation where somatic complaints cannot be explained by measurable findings[10,15]. Psychodiagnostic instruments are necessary to clarify the situation and establish an objective diagnosis. A variety of tests can be used to evaluate persons with the suspicion of a somatoform tendency[10,13,15,22-24]. Often these patients may have depression and anxiety, which can influence the clinical assessment of patients[23-25]. The basis for an optimal selection of patients with GERD for surgery is a comprehensive diagnostic work-up to generate evidence for an advanced, progressive disease with proven damage and functional defects.

Besides a good surgical technique, the optimal selection of the right patients for laparoscopic fundoplication is of utmost importance for the final result of surgical therapy. Laparoscopic fundoplication can produce an ideal solution for a patient with severe and progressive GERD, reducing most of the troublesome symptoms and enabling the patient to live a normal joyful life[12]. Having expressed this, it must be emphasized that performing a fundoplication on the wrong patient, who either does not need a fundoplication or who has other problems, which could be worsened by a fundoplication, can easily destroy the patient`s quality of life.

Patients with somatoform disorders usually have a large variety of symptoms, where typical reflux symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation may play only a limited role or may be overrated by the patient due to the stress and heavy load of all symptoms. In these cases the question emerges, whether surgery is justified. Objective diagnostic testing is essential to verify pathologic gastroesophageal reflux, but still given the tests are positive, there is still a dilemma, whether patients would benefit from antireflux surgery. Some surgeons advise to see these patients as contraindications for antireflux surgery[17,18].

Little is known about the probability of success after surgical therapy in these patients with the combined problem. Therefore the present study shows very clearly that a precise diagnostic work-up is necessary to determine the presence of a somatoform tendency as well as the presence of severe GERD. The study is helpful in showing evidence that on one hand improvement of quality of life is possible, and on the other hand that quality of life can rather not be normalized, since too many other symptoms are involved with no connection the underlying reflux problem.

The problem is that patients with GERD and somatoform disorders start from a preoperative significantly lower level of quality of life than GERD patients without somatoform tendencies. Interesting enough laparoscopic antireflux surgery can elevate the GIQLI for about 20-25 points in patients. The latter causes in GERD-patients without associated problems a postoperative quality of life level of nearly normal levels while patients with both, GERD and somatisation will usually remain in a lower level, which can cause postoperative disappointment and frustration. This should be communicated to the patients prior to surgery to make sure that the preoperative expectations will not be unrealistic.

In conclusion, patients with GERD and overlapping symptoms due to somatoform disorders should not be withhold from laparoscopic antireflux surgery in general, if their GERD is proven by objective assessment. It must be however emphasized that these patients must be especially informed about their critical situation regarding their large number of often atypical symptoms, which cannot be cured completely. The latter causes continuing restrictions in their quality of life. As a consequence the indication for antireflux surgery must be discussed in detail with the patients and only those should be selected, in whom reflux-generated-symptoms are proven by reflux symptom-correlation[26]. These symptoms should be the major quality-of-life restricting factors.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) shows a large symptom variation also in different intensities among patients. Up-to-date, patients with somatoform tendencies were often per se excluded from surgery.

There is a large overlap in the symptomatic spectrum between GERD and other disorders such as dyspepsia, functional heartburn or somatoform disorders. We intended to be able to better differentiate between these different entities to provide optimal patient care. Before our study, it was still unclear if patients with somatoform tendencies should undergo surgery at all.

The purpose of this study is an evaluation of patients with GERD with and without somatoform disorders before and after laparoscopic antireflux surgery regarding their outcome.

In the largest center for benign foregut surgery in Germany patients with GERD, qualifying for antireflux surgery were investigated prospectively regarding their symptomatic spectrum in order to identify GERD and associated somatoform disorders over a period of 3 years using an instrument for the evaluation of somatoform disorders. Quality of life was evaluated by Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI). These parameters were compared depending on the group assignment of patients.

One fifth of all included patients suffered from somatoform tendencies (20.48%; 34 patients). Patients with this tendency had a preoperative GIQLI of 77 (32-111). Patients without this tendency had a GIQLI of 105 (29-140; P < 0.0001). Quality of life could be normalized from preoperative reduced values of GIQLI 102 (47-140) to postoperative values of 117 (44-144) in patients with GERD. GIQLI of patients with GERD and somatoform tendency was improved from preoperative GIQLI 75 (47-111) to postoperative 95 (44-122; P < 0.0043).

This is the first study to show that patients with a somatoform tendency should not be excluded from surgery, however they will not reach a normal level of quality of life. Patients with GERD and somatoform disorders have an impaired quality of life. The latter patients can also benefit from laparoscopic fundoplication, however they will not reach a normal level.

The investigated instruments for assessment of quality of life and somatoform disorders can help to discriminate between the different symptom origins and should be used in all patients who undergo antireflux surgery.

| 1. | DeMeester TR. Definition, detection and pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: DeMeester TR, Matthews HR (eds) Benign esophageal disease. International trends in general thoracic surgery. Mosby St. Louis 1987; 99-127. |

| 2. | Klauser AG, Schindlbeck NE, Müller-Lissner SA. Symptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 1990;335:205-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2528] [Article Influence: 126.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Holtmann G, Kutscher SU, Haag S, Langkafel M, Heuft G, Neufang-Hueber J, Goebell H, Senf W, Talley NJ. Clinical presentation and personality factors are predictors of the response to treatment in patients with functional dyspepsia; a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:672-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Clauwaert N, Jones MP, Holvoet L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L. Associations between gastric sensorimotor function, depression, somatization, and symptom-based subgroups in functional gastroduodenal disorders: Are all symptoms equal? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:1088-e565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bradley LA, Richter JE, Pulliam TJ, Haile JM, Scarinci IC, Schan CA, Dalton CB, Salley AN. The relationship between stress and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux: The influence of psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Johnston BT, Lewis SA, Love AH. Stress, personality and social support in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tack J, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Lee KJ, Sifrim D, Janssens J. Prevalence of acid reflux in functional dyspepsia and its association with symptom profile. Gut. 2005;54:1370-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Neumann H, Monkemuller K, Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P. Dyspepsia and IBS symptoms in patients with NERD, ERD and Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis. 2008;26:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fuchs KH, Musial F, Ulbricht F, Breithaupt W, Reinisch A, Babic B, Fuchs H, Varga G. Foregut symptoms, somatoform tendencies, and the selection of patients for antireflux surgery. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Costantini M, Crookes PF, Bremner RM, Hoeft SF, Ehsan A, Peters JH, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Value of physiologic assessment of foregut symptoms in a surgical practice. Surgery. 1993;114:780-786; discussion 786-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fuchs KH, Babic B, Breithaupt W, Dallemagne B, Fingerhut A, Furnee E, Granderath F, Horvath P, Kardos P, Pointner R, Savarino E, Van Herwaarden-Lindeboom M, Zaninotto G; European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). EAES recommendations for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1753-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rief W, Hiller W. Toward empirically based criteria for the classification of somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:507-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rief W, Hessel A, Braehler E. Somatization symptoms and hypochondriacal features in the general population. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:595-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rief W, Hiller W. A new approach to the assessment of the treatment effects of somatoform disorders. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:492-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zaballa P, Crega Y, Grandes G, Peralta C. The Othmer and DeSouza test for screening of somatisation disorder: Is it useful in general practice? Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:182-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Bammer T, Pasiut M, Pointner R. Psychological intervention influences the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in patients with stress-related symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:800-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Velanovich V, Karmy-Jones R. Psychiatric disorders affect outcomes of antireflux operations for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mearin F, Ponce J, Ponce M, Balboa A, Gónzalez MA, Zapardiel J. Frequency and clinical implications of supraesophageal and dyspeptic symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:665-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kamolz T, Granderath F, Pointner R. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: disease-related quality of life assessment before and after surgery in GERD patients with and without Barrett's esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:880-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmülling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: Development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 915] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fink P. Surgery and medical treatment in persistent somatizing patients. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:439-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mussell M, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Herzog W, Löwe B. Gastrointestinal symptoms in primary care: Prevalence and association with depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:605-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: Syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:191-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cheville AL, Basford JR, Dos Santos K, Kroenke K. Symptom burden and comorbidities impact the consistency of responses on patient-reported functional outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Savarino E, Tutuian R, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Pohl D, Marabotto E, Parodi A, Sammito G, Gemignani L, Bodini G, Savarino V. Characteristics of reflux episodes and symptom association in patients with erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease: Study using combined impedance-pH off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

CONSORT 2010 Statement: The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 Statement.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P- Reviewer: Herbella F, Park JM, Sakitani K S- Editor: Yan JP L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y