Published online Apr 7, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1603

Peer-review started: February 14, 2019

First decision: February 21, 2019

Revised: February 23, 2019

Accepted: March 11, 2019

Article in press: March 12, 2019

Published online: April 7, 2019

Processing time: 48 Days and 19.7 Hours

Acute severe ulcerative colitis unresponsive to systemic steroid treatment is a life-threatening medical condition requiring hospitalization and often colectomy. Despite the increasing choice of medical therapy options for ulcerative colitis, the condition remains a great challenge in the field of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). The performance of the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus in this clinical setting is insufficiently elucidated.

To evaluate the short and long-term outcomes of tacrolimus therapy in adult inpatients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis.

We conducted a retrospective monocentric study enrolling 22 patients at a tertiary care center for the treatment of IBD. All patients who were admitted to one of the wards of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Heidelberg University Hospital with acute severe ulcerative colitis between 2007 and 2018, and who received oral or intravenous tacrolimus for steroid-refractory disease were included. Baseline characteristics and data on the disease courses were retrieved from entirely computerized patient charts. The primary study endpoint was clinical response to tacrolimus therapy, resulting in discharge from the hospital. Secondary study endpoints were colectomy rate and time to colectomy, achievement of clinical remission under tacrolimus therapy, and the occurrence of side effects.

In the majority of the 22 included patients (68.2%), tacrolimus therapy was initiated intravenously and subsequently converted to oral administration. The treatment duration was 128 ± 28.5 d (mean ± SEM), and the patients were followed up for 705 ± 110 d after treatment initiation. Among all patients, 86.4% were discharged from the hospital under continued oral tacrolimus therapy. In 36.4% of the patients, the administration of tacrolimus resulted in clinical remission at some point during the treatment. Thirty-two percent of the patients underwent colectomy between 5 and 194 d after the initiation of tacrolimus treatment (mean: 97.4 ± 20.8 d). Colectomy-free survival rates at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo after the initiation of tacrolimus therapy were 90.9%, 86.4%, 77.3% and 68.2%, respectively. The safety profile of tacrolimus was overall favorable. Only two patients discontinued the treatment due to side effects.

The short-term outcome of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis was beneficial, and side effects were rare. In all, tacrolimus therapy appears to be a viable option for short-term treatment of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis besides ciclosporin and anti-tumor necrosis factor α treatment.

Core tip: Steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis requires hospitalization and is frequently a risky tightrope walk between surgery and medical treatment. Whereas sufficient data has been provided over time to justify ciclosporin and infliximab as salvage therapies in this clinical scenario, guideline recommendations are still more reluctant towards tacrolimus due to the relative lack of data. However, tacrolimus may have advantages over ciclosporin especially due to its different toxicity profile. Our study provides more insight in the potential of tacrolimus in the strictly defined situation of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis in hospitalized patients.

- Citation: Hoffmann P, Wehling C, Krisam J, Pfeiffenberger J, Belling N, Gauss A. Performance of tacrolimus in hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(13): 1603-1617

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i13/1603.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1603

The global incidence of ulcerative colitis is increasing[1]. Ten to 15% of the patients with ulcerative colitis suffer from an episode of fulminant colitis during the course of their disease[2]. Intravenous corticosteroids remain the first-line therapy for such severe attacks[3]. However, approximately 30% of the patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis respond insufficiently to corticosteroid treatment, which necessitates some type of rescue therapy[4,5]. Conventional salvage therapies to avoid colectomy comprise antibodies against tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)—typically infliximab and calcineurin inhibitors, i.e., ciclosporin or tacrolimus, both drug classes yielding comparable results[3]. Ciclosporin and tacrolimus are efficient immuno-suppressants widely used in clinical routine to prevent allograft rejection after organ transplan-tation[6]. Ciclosporin was the first calcineurin inhibitor to be successfully tested in the clinical setting of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis[7]. Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor with a more potent inhibitory effect on activated T cells in comparison with ciclosporin, as tacrolimus influences both ciclosporin‐sensitive and ciclosporin‐insensitive T-cell activation pathways[6,8]. Ciclosporin and tacrolimus also display different toxicity profiles[9].

Regarding the treatment of acute severe ulcerative colitis, less is known about tacrolimus therapy than on ciclosporin therapy. To date, two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published on tacrolimus therapy in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: In one, two different serum trough concentrations of tacrolimus were compared to each other (5-10 ng/mL vs 10-15 ng/mL)[10]. That trial revealed a dose-dependent effect of tacrolimus; however, it was underpowered for the detection of a significant difference between the two subgroups. Another Japanese trial published by the same group examined oral tacrolimus in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis and demonstrated a clinical response rate of 50% in the tacrolimus group vs 13.3% in the placebo group after only two weeks of treatment, while the rate of clinical remission was 9.4% vs 0%[11]. Furthermore, several small and heterogeneous retrospective studies have dealt with the use of tacrolimus in severe steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis. For example, in a recently published open-label trial including 100 patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis, tacrolimus was compared to anti-TNFα treatment. Efficacy and safety data were similar in both groups[12].

This is the basis on which national and international guidelines recommend both ciclosporin or tacrolimus in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis, even though the recommendation for ciclosporin is stronger than the one for tacrolimus due to the larger quantity of available data[3,13]. The aim of the present study is to extend the knowledge on the suitability of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative, only considering critically ill patients on the verge of colectomy.

This is a retrospective single-center observational study performed at the University Hospital Heidelberg, a tertiary care center in Southwest Germany treating a large number of patients with IBD. The study embraces a time span of 12 years (January 2007 to December 2018). The cut-off time point for data acquisition was 31 December 2018. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional Ethics Committee (Alte Glockengießerei 11/1, 69115 Heidelberg, Germany; protocol number: S-006/2019). It was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2000. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

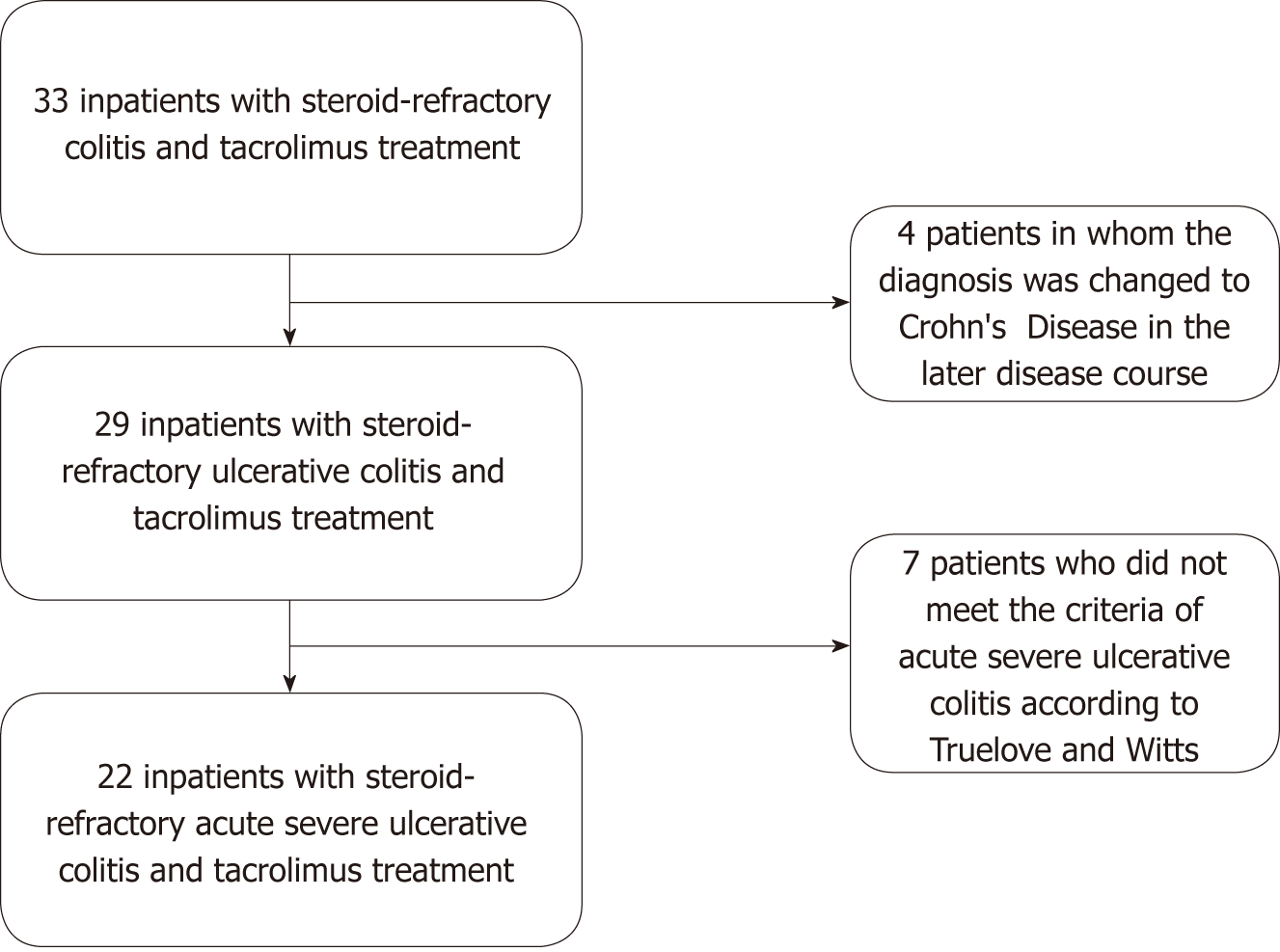

The following inclusion criteria were defined: (1) Ascertained diagnosis of ulcerative colitis according to ECCO criteria[3]; (2) endoscopic disease extent of at least Montreal E2 (left-sided colitis)[14]; (3) age of at least 18 years at the time of the initiation of tacrolimus therapy; (4) inpatient treatment at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Heidelberg University Hospital between January 2007 and October 2018; (5) presentation with an acute severe flare of ulcerative colitis according to Truelove and Witts criteria[15]; (6) no or insufficient response to intravenous prednisone or prednisolone according to national guideline recommendations[13]; (7) treatment of the flare with tacrolimus (oral or intravenous application). Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients who were already scheduled for colectomy at start of tacrolimus therapy; (2) patients in whom the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was changed to Crohn’s colitis in the follow-up after the initiation of tacrolimus therapy; (3) patients with untreated intestinal infections, including Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), Campylobacter spp., and Cytomegalovirus.

Acute severe ulcerative colitis at admission to the hospital was defined according to the Truelove and Witts criteria[15]. The Truelove and Witts[15] criteria include a stool frequency of ≥ 6 per day, and at least one of the following: Pulse rate > 90 bpm, temperature > 37.8 °C, hemoglobin concentration < 10.5 g/dL, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 30 mm/h. Steroid-refractoriness was defined as no sufficient clinical response to intravenous treatment with prednisone or prednisolone at a daily dose of 1 mg/kg body weight according to guideline recommendations[3,13].

Clinical response was defined as a significant decrease of stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and plasma C reactive protein (CRP) concentration, as well as an amelioration of general well-being as documented in the patient chart, resulting in the possibility to discharge the patient from the hospital to continue the therapy on an outpatient basis. Clinical remission was considered if a Partial Mayo Score of 0 or 1 was documented in the electronic patient chart by the treating physician[16]. Disease extent was categorized according to the Montreal classification based on all available endoscopy reports[14]. Loss to follow-up was considered when the last contact to the patient (counted from the cut-off time point for data acquisition) was more than two years ago.

Patients with a severe flare of ulcerative colitis were first treated with intravenous corticosteroids according to guideline recommendations[3,13], in case that had not already been performed at a different inpatient facility prior to the referral to our department. Intestinal infections were excluded by sigmoidoscopy and biopsies for Cytomegalovirus PCR or immunohistochemistry, and stool cultures for Salmonella, Campylobacter, Yersinia and Shigella spp. as well as an assay for C. difficile toxin. Antibiotics, mainly ciprofloxacin and metronidazole, were applied at the discretion of the treating physician, even without proof of infection, e.g., if translocation of intestinal bacteria was suspected. Intravenous nutritional support was administered in malnourished patients. Intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement as well as blood transfusions were performed as required.

Steroid-refractoriness was considered if no sufficient clinical response occurred under intravenous treatment with prednisone or prednisolone at a daily dose of 1 mg/kg for at least three d according to guideline recommendations[3,13]. In patients with steroid-refractory disease, the treating physicians’ team (always including a senior consultant in gastroenterology with experience in IBD therapy) decided on the basis of disease severity, comorbidities, patient age, prior medications, and patients’ wishes which rescue therapy was most appropriate. In most cases, a visceral surgeon was involved in the decision-making process. Tacrolimus has been used as the standard first-line rescue medication of the department in patients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis over the last two decades. It was adminis-tered every 12 h, and dosage was adjusted to blood trough levels of 10-15 ng/mL. Intravenous tacrolimus was consistently applied over six hours twice per day via a rate-controlled syringe pump, and tacrolimus trough levels were determined shortly before the morning application. The first trough level measurement was performed one or two days after treatment initiation; thereafter, tacrolimus trough concentrations were measured on a daily basis during the hospital stay. After at least four weeks of tacrolimus treatment, the target trough level was decreased to 5-10 ng/mL at the discretion of the treating physician. Where intravenous tacrolimus treatment resulted in improvement of colitis symptoms and the medication was tolerated by the patient, the treatment was continued orally at the discretion of the attending physician. Patients with distinct amelioration of disease activity according to clinical symptoms—including stool frequency, occurrence of bloody stools, abdominal cramps, and fever—were released to outpatient treatment. After the decision to initiate tacrolimus therapy was made, steroid therapy was completely discontinued or tapered off depending on the total duration of steroid treatment. The decision on the introduction of a second immunosuppressive agent during the hospital stay to maintain remission was individualized mainly according to prior therapies and the risk of opportunistic infections.

The primary study end point was clinical response to tacrolimus salvage therapy, as defined above. Secondary endpoints were clinical response under tacrolimus therapy, colectomy rate, time to colectomy, and the occurrence of side effects.

Names of suitable patients were retrieved from electronically available lists of inpatients of all wards of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Heidelberg University Hospital who were admitted between January 2007 and October 2018. All data were available as entirely electronic patient records in the Hospital Information System. The patient records were monitored until the cut-off time point for data collection on 31 December 2018, or to loss to follow-up. The following data were collected in an Excel spread sheet: Patient age, disease duration at admission to the hospital, disease extent according to the Montreal classification[14], medications for ulcerative colitis at admission and discharge from the hospital, prior nonresponse to biological therapy, endoscopic findings, laboratory findings, number of bowel movements per day, presence and amount of blood in stool, body temperature, necessity of blood transfusions, performance of colectomy and time span between initiation of tacrolimus therapy and colectomy, duration of hospital stay, duration of steroid therapy until start of tacrolimus treatment, total duration of tacrolimus therapy, results of stool cultures and rectal biopsies for Cytomegalovirus PCR, suspected side effects of tacrolimus, doses and blood trough levels of tacrolimus during the hospital stay, concomitant medications administered in the ward, subsequent ulcerative colitis therapies, reasons for discontinuation of tacrolimus therapy, and disease course after discharge from the hospital.

This is a descriptive study. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. For numerical variables, means ± standard errors of the mean (SEM) were calculated. A Kaplan-Meier survival plot was applied to illustrate cumulative colectomy-free survival. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2010 and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM corporation, Armonk, New York, United States).

The present study included 22 patients (13 females) who were treated for acute severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid treatment in one of the wards of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Heidelberg University Hospital between 2007 and 2018. Figure 1 illustrates in a flowchart how many patients had to be excluded and for which reasons. The demographic characteristics and disease-specific baseline data of the included patients are presented in detail in Table 1. The mean age at first diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was 25.5 ± 5.6 years, and the disease duration at hospitalization was 6.2 ± 1.3 years. Disease extent according to the Montreal classification[14] was mostly extensive colitis (E3). None of the patients had been treated with tacrolimus prior to their hospitalization. Prior failure to anti-TNFα therapy (but not during the hospital stay of interest) had occurred in five patients (22.7%). At admission to the hospital, the patients’ mean plasma CRP concentration was 87.5 ± 14.3 mg/L (normal: < 5 mg/L), the body temperature 38.0 ± 0.2 °C, the heart rate 97.2 ± 2.9 bpm, and the number of bowel movements 13.5 ± 1.4 per 24 h.

| Characteristic | n = 22 |

| Gender, n (m/f) | 9/13 |

| Age at admission (yr, mean ± SEM) | 33.2 ± 7.1 (range: 18-66) |

| Age at first diagnosis (yr, mean ± SEM) | 25.5 ± 5.6 (n = 21, uk in 1) (range: 14-58) |

| Disease duration at admission (yr, mean ± SEM ) | 6.2 ± 1.3 (n = 21, uk in 1) (range: 0-19) |

| Disease extent according to Montreal classification at admission, n (E2:E3) | 4:18 |

| Previous anti-TNFα therapy failure, n (%) | 5/22 (22.7) |

| Previous thiopurine therapy, n (%) | 9/22 (40.9) |

| Systemic steroid therapy at admission, n (%) | 15/22 (68.2) |

| Oral mesalamine at admission, n (%) | 15/22 (68.2) |

| Anti-TNFα therapy at admission, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) (third infliximab infusion had been applied 23 d prior to admission) |

| Thiopurine therapy at admission, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) (on azathioprine for 32 mo prior to admission) |

| Body mass index (BMI) at admission (kg/m2, mean ± SEM) | 20.3 ± 4.3 (range: 12.1-26.8) |

| Body temperature at admission (°C, mean ± SEM) | 38.0 ± 0.2 (range: 36.6-39.6) |

| Heart rate at admission (beats per minute, mean ± SEM) | 97.2 ± 2.9 (range: 80-135) |

| Number of bowel movements per 24 h at admission (mean ± SEM) | 13.5 ± 1.4 (range: 7-30) |

| Presence of bloody stools at admission, n (%) | 22/22 (100) |

| Plasma CRP concentration at hospital admission (mg/L, mean ± SEM) | 87.5 ± 14.3 (range: 2.0-310.4) |

| WBC count at admission (/nL, mean ± SEM) | 12.6 ± 1.0 (range: 4.4-22.8) |

| Platelet count at admission (/nL, mean ± SEM) | 453 ± 29 (232-724) |

| Blood hemoglobin concentration at admission (g/dL, mean ± SEM) | 10.8 ± 0.3 (7.7-14.5) |

| Endoscopic Mayo score at admission, n (Mayo 2:Mayo 3) (sigmoidoscopy) | 7:15 |

The average time span between the first dose of tacrolimus and the last follow-up visit was 705 ± 110 d (range: 63-1870 d). In total, six patients (27.3%) were lost to follow-up at the cut-off time point for data acquisition. The time to loss to follow-up ranged from 65 to 1557 d (mean: 107 ± 225 d). It was shorter than one year in only one patient.

The average duration of hospitalization was 22.8 ± 4.9 d. Further characteristics of the study cohort during the hospital stay may be viewed in Table 2. Notably, all but one of the patients received empirical systemic antibiotic treatment at admission, mostly intravenous ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole, for suspected septic complications without positive blood cultures. At that, parenteral nutritional support was administered in nine patients (40.9%), and ten patients received at least one blood transfusion during their hospital stay (45.5%).

| Variable | n = 22 |

| Systemic antibiotic treatment during hospital stay, n (%) | 21/22 (95.5) |

| Duration of IV steroid therapy prior to start of tacrolimus therapy (mean ± SEM) | 6.7 ± 0.7 |

| Use of parenteral nutrition during hospital stay, n (%) | 9/22 (40.9) |

| Blood transfusion during hospital stay, n (%) | 10/22 (45.5) |

| Oral mesalamine therapy during hospital stay, n (%) | 17/22 (77.3) |

| Stay in intermediate care unit during part of the hospitalization, n (%) | 4/22 (18.2) |

| Duration of hospital stay, d (mean ± SEM) | 22.8 ± 4.9 |

| Addition of a second immunosuppressive as a maintenance therapy during hospital stay, n (%) | 10/22 (45.5) |

| Anti-integrin (vedolizumab) | 5/22 (22.7) |

| Thiopurine (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) | 5/22 (22.7) |

In 15 of the 22 included patients (68.2%), tacrolimus therapy was initiated intravenously, while seven patients (31.8%) received oral tacrolimus from the start. The initial dose for intravenous tacrolimus was 1.4 ± 0.4 mg/24 h, corresponding to 26 ± 3 μg/kg body weight, while dosage was 5.3 ± 2.2 mg/24 h for oral treatment initiation, corresponding to 95 ± 31 μg/kg body weight. Overall, the target trough concentration of 10-15 ng/ml was reached after 3.1 ± 0.8 d. The time until achievement of target trough concentration was longer for the oral than for the intravenous treatment scheme (4.2 ± 1.2 vs 3.1 ± 0.4 d, n = 21, as one patient discontinued the therapy due to side effects on day 2). The mean oral tacrolimus dose per 24 h at the time of discharge from the hospital (n = 19) was 10.2 ± 1.1 mg (equaling 186 ± 23 μg/kg body weight). The mean duration of intravenous tacrolimus treatment was 4.0 ± 0.9 d. The total duration of tacrolimus treatment during hospitalization was 15.9 ± 3.4 d. The mean total duration of tacrolimus therapy (duration of inpatient treatment plus duration of outpatient treatment) was 128 ± 28.5 d.

At hospital admission, 15 patients (68.2%) were already undergoing oral systemic steroid therapy with prednisone or prednisolone, one patient was on infliximab, and one patient on azathioprine. In all, 12 patients (54.5%) received oral mesalamine and three patients (13.6%) oral budesonide to treat IBD. As part of the therapeutic concept of using tacrolimus as a bridge to a less toxic maintenance therapy, five patients (22.7%) were started on vedolizumab while hospitalized, while thiopurine therapy was introduced in five patients (22.7%). None of the patients was administered a TNFα antibody during inpatient treatment.

All but three patients (86.4%) were discharged from the hospital under continued oral tacrolimus treatment. Distinct primary treatment failure of tacrolimus despite achievement of target trough levels was observed in two patients (9.1%), resulting in their direct transfer to the surgery department for subtotal colectomy. In one patient, tacrolimus was discontinued after two days due to severe vomiting. Clear clinical response to tacrolimus indicated by a reduction of stool frequency and a reduction or disappearance of blood in stool was documented in 18 patients (81.8%). One patient was discharged from the hospital on her own urgent wish even though distinct clinical response to tacrolimus had not occurred. In that patient, the therapy was changed to adalimumab after discharge from the hospital, and she achieved clinical remission under that therapy. Six patients (27.3%) achieved complete clinical remission at some point during their tacrolimus therapy which was attributable to the calcineurin inhibitor and not to any concomitant medication.

Directly prior to the first administration of tacrolimus, the mean plasma CRP concentration was 87.5 ± 12.2 mg/L, and it decreased to 24.3 ± 10.5 mg/L at discharge from the hospital (n = 20, the two patients who were transferred to the surgery department were excluded). It was 51.5 ± 11.4 mg/L at day 5 of tacrolimus therapy and 42.9 ± 11.8 mg/L at day 7 of tacrolimus therapy. The occurrence of blood in stool was documented in 100% of the patients at admission to the hospital, while blood in stool was documented in 11/20 (55%) patients at discharge from the hospital. The mean stool frequency was 13.5 ± 1.4 at admission (n = 22) and decreased to 5.4 ± 0.6 at discharge (n = 20). The mean body temperature at admission was 38.0 ± 0.2 °C at admission, decreasing to 36.9 ± 0.1 °C at discharge from the hospital.

The most prevalent event (36% of cases) resulting in discontinuation of tacrolimus therapy in this study was medium-term treatment failure after discharge from the hospital, including inadequate response and secondary treatment failure. In 27% of the patients, tacrolimus was stopped after initial response and after introduction of an overlapping immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine or vedolizumab in order to find out whether the immunosuppressant intended for maintenance therapy was successful as monotherapy. The whole spectrum of reasons for tacrolimus discon-tinuation is presented in detail in Figure 2.

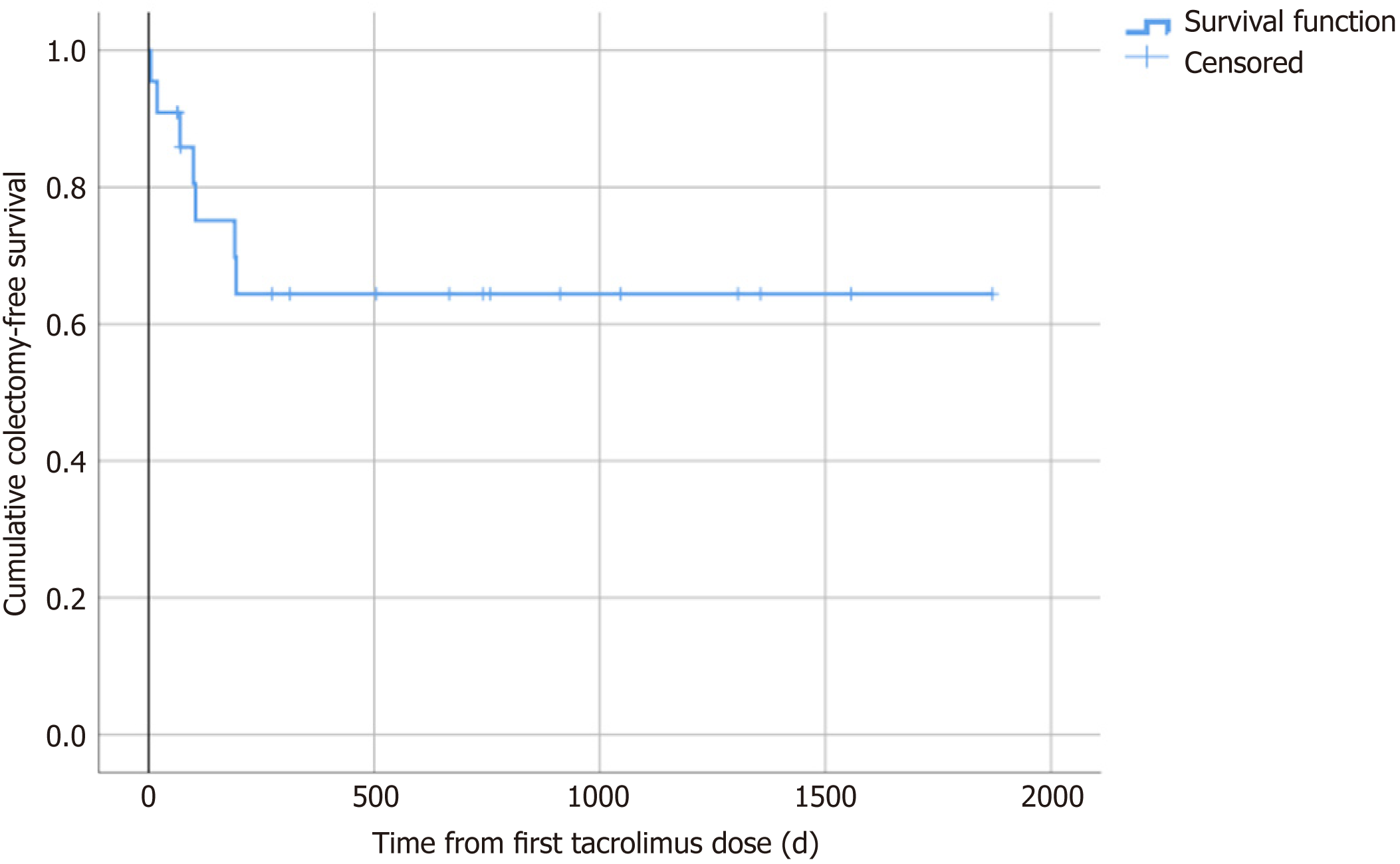

Seven among the 22 included patients (31.8%) underwent colectomy for treatment-refractory ulcerative colitis during the follow-up after the initiation of rescue therapy with tacrolimus. The mean time span from the initiation of tacrolimus therapy to surgical intervention was 97.4 ± 20.8 d (range: 5-194 d) (Table 3 and Figure 3). Two patients (9.1%) underwent colectomy within one month of the initiation of tacrolimus therapy, three (13.6%) within three mo, five (22.7%) within six mo, and seven (31.8%) within 12 mo. Vice versa, colectomy-free survival rates at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo were 90.9%, 86.4%, 77.3% and 68.2%, respectively.

| Variable | n = 22 |

| Intravenous initiation of tacrolimus treatment, n (%) | 15/22 (68.2) |

| Duration of intravenous tacrolimus therapy (d, mean ± SEM) | 4.0 ± 0.9 (range: 2-13) |

| Duration of tacrolimus therapy until discharge from the hospital or transfer to surgery (d, mean ± SEM) | 15.9 ± 3.4 (n = 20) |

| Initial dose of intravenous tacrolimus (mg/24 h, mean ± SEM) | 1.4 ± 0.4 (n = 15) |

| Initial dose of intravenous tacrolimus per body weight (μg/kg/24 h, mean ± SEM) | 26 ± 3 (n = 15) |

| Initial dose of oral tacrolimus (mg/24 h, mean ± SEM) | 5.3 ± 2.2 (n = 7) |

| Initial dose of oral tacrolimus per body weight (μg/kg/24 h, mean ± SEM) | 95 ± 31 (n = 7) |

| Time to achievement of target tacrolimus trough level after intravenous treatment initiation (d, mean ± SEM) | 3.1 ± 0.4 (n = 14) |

| Time to achievement of target tacrolimus trough level after oral treatment initiation (d, mean ± SEM) | 4.2 ± 1.2 (n = 7) |

| Total duration of tacrolimus therapy to end of therapy or last follow-up (d, mean ± SEM) | 128 ± 28.5 (range: 2-266) |

| Patients discharged from the hospital under continued tacrolimus therapy, n (%) | 19/22 (86.4) |

| Clinical response to tacrolimus therapy, including remission, n (%) | 18/22 (81.8) |

| Clinical remission under tacrolimus therapy, n (%) | 8/22 (36.4) |

| Colectomy during follow-up, n (%) | 7/22 (31.8) |

| Direct transmission to the surgery department after primary failure of tacrolimus therapy, n (%) | 2/22 (9.1) |

| Time from start of tacrolimus therapy to colectomy (d, mean ± SEM) | 97.4 ± 20.8 (range: 5-194) |

At the time of their last follow-up visits at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Heidelberg University Hospital, only three patients were on continued tacrolimus therapy. Two of them were in clinical remission at that time point. In total (independent of whether tacrolimus therapy was ongoing), the outcome of all included 22 patients at their respective last follow-up visits was as follows: 8/22 patients (36.4%) were in clinical remission, and 7/22 patients had undergone colectomy (31.8%); ongoing disease activity was documented in 7/22 patients (31.8%).

Among the eight patients with documented clinical remission at their last follow-up visits, one was under therapy with tacrolimus and oral mesalamine, one under a combination therapy with tacrolimus and vedolizumab (induction with vedolizumab not yet finished), four under infliximab monotherapy, one under adalimumab monotherapy, and one under azathioprine monotherapy.

Among the seven patients with documented disease activity at their last follow-up visits, one was under therapy with tacrolimus and vedolizumab, one under therapy with systemic steroids and vedolizumab, two under systemic steroid treatment alone, one under adalimumab monotherapy, one under azathioprine monotherapy, and one under mesalamine monotherapy.

Among the five patients in whom vedolizumab therapy was initiated after having achieved clinical response to tacrolimus as a maintenance concept during the hospital stay, three had to discontinue their vedolizumab therapy due to lack of response after the induction had been completed, and all three patients underwent colectomy. Two of these three patients had also failed on anti-TNFα treatment before. One of the patients on tacrolimus and vedolizumab combination therapy had not undergone at least 10 wk of vedolizumab at the cut-off time point for data acquisition, so that the effect of vedolizumab could not be assessed in this patient. In none of the five patients, the combination of tacrolimus and vedolizumab resulted in serious infections. In our study, five patients received additional thiopurine therapy after treatment initiation with tacrolimus: one of them underwent colectomy, three stopped azathioprine therapy for treatment failure and changed to a different regimen, and one discontinued 6-mercaptopurine therapy because of side effects.

Only adverse events that were suspected to be caused by tacrolimus were considered. In none of the cases was tacrolimus treatment discontinued because of an infectious complication. No patients died during the follow-up period. The suspected side effects of tacrolimus in our study cohort are listed in detail in Table 4. The most frequently documented side effect was tremor of the limbs, especially of the hands. It was dose-dependent and provoked therapy interruption in none of the cases. It was completely reversible after tacrolimus had been stopped for other reasons. Two patients discontinued tacrolimus therapy because of intolerable suspected side effects. One male ended treatment because of severe nausea and vomiting after a treatment duration of only two days; in that patient, ciclosporin was subsequently tried and discontinued for the same reason. The other had to stop her intake of tacrolimus for anemia and leukopenia after 50 d, when she presented as an outpatient for a follow-up of her disease course. That patient was on treatment with 6-mercaptopurine at the same time, so the side effect cannot be definitely attributed to tacrolimus. We also analyzed glomerular filtration rates determined directly prior to the start of tacrolimus therapy and at discharge from the hospital: they were 114.9 ± 26.4 mL/min vs 111.7 ± 25.6 mL/min, arguing against a short-term detrimental effect of tacrolimus on renal function at the high doses that were administered.

| Suspected side effect | n = 22 |

| None, n (%) | 10/22 (45.5) |

| Treatment discontinuation due to side effects, n (%) | 2/22 (9.1) (1 due to severe vomiting, 1 due to anemia and leukopenia) |

| Nausea ± vomiting, n (%) | 3/22 (13.6) |

| Stomach pain, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Headache, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Tremor, n (%) | 4/22 (18.2) |

| Paresthesias, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Photosensitivity, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Itching rash, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Joint or back pain, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Muscle pain or cramps, n (%) | 2/22 (9.1) |

| Temperature intolerance, n (%) | 3/22 (13.6) |

| Anemia, leukopenia, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Loss of hair, n (%) | 1/22 (4.5) |

We performed a retrospective analysis to explore both the short and long-term outcomes of tacrolimus rescue therapy in hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. Non-response to steroid treatment in ulcerative colitis represents a negative selection concerning other classes of immunosuppressive medications. The key finding of our study is that in this critically ill group of patients, tacrolimus had a very beneficial short-term effect and was able to prevent direct referral to the surgery department for colectomy in the vast majority of cases. However, in the long term, outcome results became more disappointing, as can be best derived from a cumulative colectomy rate of 31.8% at a mean of 97.4 d after the initiation of tacrolimus therapy.

Data on the long-term outcome of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis are overall scarce. Cohort studies on the performance of tacrolimus in the treatment of ulcerative colitis have been published by several other authors, starting in 1998 by Fellermann et al[17], who presented a case series of six patients with ulcerative colitis and five with Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis. The largest published patient series covered 156 patients from five treatment facilities suffering from moderate to severe courses of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis[18]. In the majority of these studies, tacrolimus was administered orally from the beginning, and study populations were rather non-homogeneous. Also, many of the studies - including the only two RCTs on this subject - originated from Japan, so the number of published data in North America and Europe is limited. Our rationale for adding another study to the body of research on this subject was that published trials on the use of tacrolimus in ulcerative colitis for the most part do not focus on the distinct situation of acute severe ulcerative colitis in the hospital ward setting. However, it is exactly that scenario where calcineurin inhibitors with their advantage of short elimination half-life may have ongoing importance in the treatment algorithm of ulcerative colitis, even if its long-term use is not recommended[13]; treatment options must therefore take into consideration which other - possibly more slowly acting medication - may supplement tacrolimus after its successful initiation[3,13].

The question may be raised why we used tacrolimus as the standard medical salvage therapy in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. At our department, tacrolimus is preferred over ciclosporin in patients who underwent liver transplantation. This choice is made for the following reasons: Liver-transplant patients treated with tacrolimus were less likely to experience acute rejection than those receiving ciclosporin[19]; mortality and graft loss at one year were significantly reduced in tacrolimus-treated liver-transplant recipients[20]; and finally, conversion from ciclosporin to tacrolimus has been shown to improve the cardiovascular risk profile in patients after liver transplantation[21]. Owing to our experience with tacrolimus, which is based on the relatively large number of liver-transplant patients followed up at our department, the administration of tacrolimus to patients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis has become our standard approach over the last one to two decades. The most important reason for the preference of tacrolimus over anti-TNFα was its shorter elimination half-time. Thus, ciclosporin and infliximab were used much less frequently than tacrolimus in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis.

The two most prominent features characterizing the present study are the strict inclusion criteria, ensuring a very homogeneous study population, and the long follow-up time with the maximal time span being 5.1 years. According to ECCO guidelines[3], patients with bloody diarrhea ≥ 6/day and any signs of systemic toxicity (pulse > 90/min, temperature > 37.8 °C, hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL, ESR > 30 mm/h, or CRP > 30 mg/L) have severe colitis and should be admitted to a hospital for intensive treatment. Our study cohort consists exclusively of patients with considerable disease activity, all meeting the criteria by Truelove and Witts[15] for the definition of acute severe ulcerative colitis, necessitating in-ward treatment. The severity of disease in our cohort is illustrated by the large percentages of patients receiving systemic antibiotic treatment, intravenous nutrition support, and blood transfusions, and by the fact that nearly 20% of the patients needed transient intermediate care treatment during their hospitalization. Of note, this is a selection of critically ill patients in whom perpetuating medical therapy may be life-threatening, and timely performed colectomy may be the better alternative.

Despite the severity of disease, our study revealed very good short-term outcomes of tacrolimus therapy in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis: As many as 86.4% of the patients were discharged from the hospital with ongoing oral tacrolimus therapy. Overall clinical response was documented in 81.1% of the patients (one patient was released with only slight amelioration of her symptoms on her own urgent request). Clinical remission under tacrolimus therapy not attributed to any other medication occurred in 36.4% of patients. Two patients were already on thiopurine or anti-TNFα (infliximab) therapy, respectively, when they were admitted to the hospital. As they had been on their therapies for 9 wk (infliximab) and 32 mo (azathioprine) when they were admitted to the hospital with acute severe ulcerative colitis, we do not think that their prior therapies interfered with our results of response to tacrolimus therapy.

A meaningful outcome parameter which is routinely used in many studies dealing with the treatment of acute severe ulcerative colitis is the cumulative colectomy-free survival over time after medical treatment initiation. That is why we explored cumulative colectomy-free survival rates at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo after the first administration of tacrolimus; our data shows 90.9%, 86.4%, 77.3% and 68.2% survival rates, respectively. Of critical note, however, is that the rate of colectomy in our study may have been underestimated due to the loss to follow-up of some patients. However, only one patient was lost to follow-up within one year of the initiation of tacrolimus therapy. A recent meta-analysis on tacrolimus treatment of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis revealed colectomy-free survival rates of 86%, 84%, 78% and 69% at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo[22]. Thus, the colectomy-free survival rates were fairly similar to those we identified in our relatively small study. A recent European prospective randomized controlled multi-center study compared colectomy-free survival rates of patients treated with ciclosporin or infliximab for steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis[23]. The authors found colectomy-free survival rates after one year of 70.9% for patients initially treated with ciclosporin and of 69.1% for patients initially treated with infliximab. Both treatments thus showed similar efficacy. The one-year colectomy-free survival rate of 68.2% identified for tacrolimus treatment in our study is in the same range and argues against the inferiority of tacrolimus to ciclosporin and infliximab for this indication. It is of note that the risk of colectomy appears to be highest within the first year after initiation of medical salvage therapy, independent of other therapies which may have been introduced subsequently or additionally during the span of the year.

No systematically obtained results have been published on the question of how tacrolimus should best be administered in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. In nearly all published studies on tacrolimus in acute severe ulcerative colitis, tacrolimus was administered orally from the beginning[24]. A potential advantage of initial intravenous treatment is that the target trough level and thus efficacy may be achieved more rapidly than by using oral tacrolimus, keeping in mind that acute severe ulcerative colitis is a highly time-sensitive situation with impending emergency colectomy. Food intake is known to reduce serum levels of tacrolimus due to its low absorption rate[11,25]. In our study, the time until achievement of the target tacrolimus trough level was indeed one day shorter in the intravenously treated subgroup compared to the orally treated subgroup. As far as it can be assessed in the relatively small subgroups, the prevalence and intensity of side effects did not differ between the intravenous and the oral administration route, so intravenous treatment should be considered, especially if the patient tends to suffer from nausea and vomiting, which may both be further provoked by the oral intake of more medications. Yamamoto et al[12] started oral tacrolimus therapy at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg/day and reached the aspired tacrolimus trough concentration of 10-15 ng/mL on day 5. In comparison, we used similar initiation doses and reached the target concentration on day 4. On one hand, it may be favorable to start the therapy at a higher dose, then quickly reduce it later on if the targeted range has been surpassed. On the other hand, the small therapeutic index of tacrolimus may result in severe side effects and possibly premature treatment discontinuation using such an approach.

As soon as patients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis respond to a medical rescue therapy with a calcineurin inhibitor or TNFα antibody, the question remains: how to maintain the response or, ideally–remission, as tacrolimus is not recommended as a long-term maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis due to its expected long-term toxicity[13]. Indeed, we can unfortunately not add more data on long-term side effects of tacrolimus in the cohort of young people suffering from ulcerative colitis, as according to our standard operating procedure, tacrolimus was only used as a bridging therapy. However, these data may differ from data obtained in patients after organ transplantation who are usually older than the patients described in our study and who are often treated with more than one immuno-suppressant concurrently. As for the choice of an additional immunosuppressant for maintenance therapy following successful treatment initiation with tacrolimus, there have been two common options during our study phase: The use of a thiopurine like azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine, or, more recently, the anti-integrin antibody vedolizumab. This choice has to be made on an individual base taking into consideration patient age, prior therapies, concomitant diseases, potential intolerances and access to outpatient intravenous therapies. Data have been published on both of these two options. For example, Schmidt et al[18] conducted a multi-center study examining the role of purine analogues in the long-term outcome of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis after tacrolimus treatment. In that study, colectomy was performed in 29% (45/156) of patients after a median of 0.5 years from initiation of tacrolimus treatment. One percent of the patients on tacrolimus plus a purine analogue had to discontinue therapy due to adverse events, while 14% of the patients on tacrolimus monotherapy discontinued treatment due to side effects. Among the five patients who were started on azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine shortly after the initiation of tacrolimus therapy in our study, the concept proved to be successful in none, but no serious infections were documented. The combination of a calcineurin inhibitor and vedolizumab for remission induction and maintenance therapy in steroid-refractory severe ulcerative colitis was addressed in a recent study from France[26]. After a median follow-up period of 11 mo, 11 patients (28%) had undergone colectomy. At 12 mo, 68% of the patients survived without colectomy and 44% survived without vedolizumab discontinuation. Analyzing our small subgroup of five patients receiving vedolizumab after tacrolimus initiation, three had to undergo surgery for refractoriness to the anti-integrin antibody, and in two, the final outcome was not clear when they visited the outpatient clinic for the last time.

The adverse events which occurred under the therapy with tacrolimus were mostly mild or moderate. Only two patients stopped the therapy due to adverse events, neither of those a life-threatening situation. These results largely conform to those of other studies on tacrolimus in ulcerative colitis[22]. However, as according to our standard operating procedure–tacrolimus was perceived as a bridging therapy to a different immunosuppressive medication with fewer expected long-term side effects, our study results do not allow for an assessment of long-term toxicity of tacrolimus.

There are several limitations to this study. The main drawbacks are its being restricted to a single treatment center and its retrospective, uncontrolled design. Due to the relatively small number of patients, this study was underpowered to perform regression analyses and thus to identify risk factors for primary treatment failure of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. Also, we have not treated a sufficient number of patients with infliximab or ciclosporin during the time span of the study, so that a controlled comparison between different treatment groups could not be incorporated in the study. Even though the follow-up rate of this study is satisfactory, considering that the study spans over 12 years, some patients were lost to follow-up, which may have influenced our results, especially those of colectomy rates. Documentation of short-term outcomes was overall very thorough, as the patients were treated in the hospital ward. However, disease scores were not calculated on a routine basis, so they could not be incorporated in the study. Laboratory markers in the blood were determined every day due to the severity of disease and impending colectomy, but stool markers such as lactoferrin and calprotectin were not regularly determined, especially in the first half of the study period, as those measurements had not entered clinical routine at that time. Also, endoscopies were only performed before the start of therapy and not repeated to assess the short-term efficacy of tacrolimus. Due to the retrospective character of the study, the term of “clinical response” was not clearly defined by quantitative parameters or cut-off values and depended much on the assessment by the treating physicians. This is why we chose to also incorporate the possibility to discharge the patient from the hospital into the definition of “clinical response”, as this is a relatively “hard” clinical endpoint in the “real world”.

Nearly all of the patients were on systemic antibiotic treatment, which was usually started directly upon hospital admission. These interventions were not performed as part of a standard operating procedure for the treatment of acute severe ulcerative colitis, as the use of antibiotics for ulcerative colitis itself is contrversial[27]. Treatment decisions were made at the discretion of the attending physicians’ team and reflect the concern of septic complications in this critically ill patient group. However, there are data from studies demonstrating some effects of antibiotics on disease activity in acute severe ulcerative colitis, and these effects may have interfered with our efficacy data of tacrolimus[28]. This potential confounder was probably minor in our study, as: (1) Antibiotic treatment was started before tacrolimus therapy – together with steroid therapy – and did not obviate the need of tacrolimus use; (2) all but one of the included patients received antibiotics, which ensures homogeneity of the study population, and (3) plasma CRP concentrations were similar at admission and on the day prior to the start of tacrolimus therapy, by which the argument could be made against any significant therapeutic effects of not only the steroids, but also the antibiotics in our cohort.

In conclusions, in a retrospective analysis including 22 inpatients suffering from steroid-refractory acute severe colitis, we found that the vast majority of patients could be discharged from the hospital after introduction of intravenous or oral tacrolimus therapy, while only two patients had to undergo surgery after primary failure of tacrolimus treatment. We conclude that the short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in this situation is very good. However, long-term evaluations revealed that in spite of initial response to tacrolimus therapy, the cumulative colectomy rate after one year for inpatients in the described clinical scenario was as high as 31.8%. It remains to be elucidated whether novel therapeutic options with a potential of rapid efficacy are able to effect the relatively high short- to medium-term colectomy rates observed after hospitalization of ulcerative colitis patients for acute steroid-refractory flares, and how these novel treatment options compare to either calcineurin inhibitors or TNFα antagonists as rescue medications. For future research projects, a direct prospective comparison of ciclosporin and tacrolimus as has already been performed in transplantation medicine would also be interesting in the setting of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis.

Steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis is a life-threatening medical condition requiring hospitalization and frequently emergency colectomy. Although there is a steadily growing choice of medications for ulcerative colitis, the treatment of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis continues to be very challenging. Calcineurin inhibitors - mainly ciclosporin and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) antagonists have been shown to be viable therapeutic options to avoid colectomy in this scenario.

In contrast to that of ciclosporin, the performance of the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus in the clinical setting of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis is insufficiently elucidated, but nonetheless recommended in national and international treatment guidelines for ulcerative colitis.

The objective of our study was to extend the current knowledge on the use of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis by assessing the short- and long-term outcomes of tacrolimus in adult inpatients suffering from steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis.

We conducted a retrospective monocentric study enrolling 22 patients at a tertiary care center for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. All patients who were admitted to one of the wards of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Heidelberg University Hospital with acute severe ulcerative colitis between 2007 and 2018 and who received oral or intravenous tacrolimus for steroid-refractory disease were included. Baseline characteristics and data on the disease courses were obtained from entirely computerized patient charts. The key study endpoints were clinical response to tacrolimus therapy, colectomy rate, time to colectomy and the occurrence of side effects.

Our study revealed that intravenous or oral tacrolimus, as in previous studies by other authors ciclosporin and infliximab, was able to prevent emergency colectomy in the majority of adult inpatients with steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis. At the same time, the safety profile of high-dose tacrolimus in this setting was acceptable. However, colectomy rates due to therapy-refractory disease courses over the year following tacrolimus rescue therapy reached nearly one-third of the patients. These results are also comparable to those of other studies dealing with the use of ciclosporin or infliximab in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis.

In all, tacrolimus appears to be a viable option for short-term treatment of steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis besides ciclosporin and anti-TNFα treatment.

Even though not recommended for long-term maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis, tacrolimus is a valuable tool for the short-term treatment of steroid-refractory severe ulcerative colitis, where rapid induction of symptom relief is warranted to gain time for the introduction of other, more slowly acting substances, with more favorable long-term toxicity profiles. Prospective trials are required to define its role among other medications, and to examine the safety of an overlapping combined use with these medications.

We thank Christopher Warren Gauss for proof-reading the manuscript.

| 1. | Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390:2769-2778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2677] [Cited by in RCA: 4466] [Article Influence: 496.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (111)] |

| 2. | Edwards FC, Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (21)] |

| 3. | Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kucharzik T, Molnár T, Raine T, Sebastian S, de Sousa HT, Dignass A, Carbonnel F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 911] [Article Influence: 101.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: A systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gustavsson A, Halfvarson J, Magnuson A, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, Järnerot G. Long-term colectomy rate after intensive intravenous corticosteroid therapy for ulcerative colitis prior to the immunosuppressive treatment era. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2513-2519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Almawi WY, Melemedjian OK. Clinical and mechanistic differences between FK506 (tacrolimus) and cyclosporin A. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1916-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1217] [Cited by in RCA: 1191] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kunz J, Hall MN. Cyclosporin A, FK506 and rapamycin: More than just immunosuppression. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ekberg H, Bernasconi C, Nöldeke J, Yussim A, Mjörnstedt L, Erken U, Ketteler M, Navrátil P. Cyclosporine, tacrolimus and sirolimus retain their distinct toxicity profiles despite low doses in the Symphony study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2004-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ogata H, Matsui T, Nakamura M, Iida M, Takazoe M, Suzuki Y, Hibi T. A randomised dose finding study of oral tacrolimus (FK506) therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2006;55:1255-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ogata H, Kato J, Hirai F, Hida N, Matsui T, Matsumoto T, Koyanagi K, Hibi T. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral tacrolimus (FK506) in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:803-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yamamoto T, Shimoyama T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Tacrolimus vs. anti-tumour necrosis factor agents for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: A retrospective observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:705-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Authors. ; Collaborators:. Updated S3-Guideline Ulcerative Colitis. German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS). Z Gastroenterol. 2019;57:162-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV, Peña AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2148] [Cited by in RCA: 2425] [Article Influence: 202.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; preliminary report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1954;2:375-378. |

| 16. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2325] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fellermann K, Ludwig D, Stahl M, David-Walek T, Stange EF. Steroid-unresponsive acute attacks of inflammatory bowel disease: Immunomodulation by tacrolimus (FK506). Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1860-1866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schmidt KJ, Müller N, Dignass A, Baumgart DC, Lehnert H, Stange EF, Herrlinger KR, Fellermann K, Büning J. Long-term Outcomes in Steroid-refractory Ulcerative Colitis Treated with Tacrolimus Alone or in Combination with Purine Analogues. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fung JJ, Eliasziw M, Todo S, Jain A, Demetris AJ, McMichael JP, Starzl TE, Meier P, Donner A. The Pittsburgh randomized trial of tacrolimus compared to cyclosporine for hepatic transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:117-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McAlister VC, Haddad E, Renouf E, Malthaner RA, Kjaer MS, Gluud LL. Cyclosporin versus tacrolimus as primary immunosuppressant after liver transplantation: A meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1578-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Beckebaum S, Klein C, Varghese J, Sotiropoulos GC, Saner F, Schmitz K, Gerken G, Paul A, Cicinnati VR. Renal function and cardiovascular risk profile after conversion from ciclosporin to tacrolimus: Prospective study in 80 liver transplant recipients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:834-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Komaki Y, Komaki F, Ido A, Sakuraba A. Efficacy and Safety of Tacrolimus Therapy for Active Ulcerative Colitis; A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:484-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, Allez M, Bouhnik Y, Filippi J, Zerbib F, Savoye G, Vuitton L, Moreau J, Amiot A, Cosnes J, Ricart E, Dewit O, Lopez-Sanroman A, Fumery M, Carbonnel F, Bommelaer G, Coffin B, Roblin X, van Assche G, Esteve M, Farkkila M, Gisbert JP, Marteau P, Nahon S, de Vos M, Lambert J, Mary JY, Louis E; Groupe d'Etudes Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Long-term outcome of patients with steroid-refractory acute severe UC treated with ciclosporin or infliximab. Gut. 2018;67:237-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Matsuoka K, Saito E, Fujii T, Takenaka K, Kimura M, Nagahori M, Ohtsuka K, Watanabe M. Tacrolimus for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Intest Res. 2015;13:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, Nouda S, Ishida K, Abe Y, Nogami K, Hida N, Yamagami H, Watanabe K, Umegaki E, Nakamura S, Arakawa T, Higuchi K. Effects of oral tacrolimus as a rapid induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1880-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pellet G, Stefanescu C, Carbonnel F, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Roblin X, Allimant C, Nachury M, Nancey S, Filippi J, Altwegg R, Brixi H, Fotsing G, de Rosamel L, Shili S, Laharie D; Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif. Efficacy and Safety of Induction Therapy With Calcineurin Inhibitors in Combination With Vedolizumab in Patients With Refractory Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:494-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ledder O, Turner D. Antibiotics in IBD: Still a Role in the Biological Era? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1676-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Turner D, Levine A, Kolho KL, Shaoul R, Ledder O. Combination of oral antibiotics may be effective in severe pediatric ulcerative colitis: A preliminary report. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1464-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: M’Koma AE, Shrestha B, Tao R S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Song H