Published online Dec 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5351

Peer-review started: October 30, 2018

First decision: November 6, 2018

Revised: November 29, 2018

Accepted: December 13, 2018

Article in press: December 13, 2018

Published online: December 21, 2018

Processing time: 52 Days and 13.5 Hours

To examine the effect of Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) on the microenvironment of colonic neoplasms and the expression of inflammatory mediators and microRNAs (miRNAs).

Levels of F. nucleatum DNA, cytokine gene mRNA (TLR2, TLR4, NFKB1, TNF, IL1B, IL6 and IL8), and potentially interacting miRNAs (miR-21-3p, miR-22-3p, miR-28-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-135b-5p) were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) TaqMan® assays in DNA and/or RNA extracted from the disease and adjacent normal fresh tissues of 27 colorectal adenoma (CRA) and 43 colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. KRAS mutations were detected by direct sequencing and microsatellite instability (MSI) status by multiplex PCR. Cytoscape v3.1.1 was used to construct the postulated miRNA:mRNA interaction network.

Overabundance of F. nucleatum in neoplastic tissue compared to matched normal tissue was detected in CRA (51.8%) and more markedly in CRC (72.1%). We observed significantly greater expression of TLR4, IL1B, IL8, and miR-135b in CRA lesions and TLR2, IL1B, IL6, IL8, miR-34a and miR-135b in CRC tumours compared to their respective normal tissues. Only two transcripts for miR-22 and miR-28 were exclusively downregulated in CRC tumour samples. The mRNA expression of IL1B, IL6, IL8 and miR-22 was positively correlated with F. nucleatum quantification in CRC tumours. The mRNA expression of miR-135b and TNF was inversely correlated. The miRNA:mRNA interaction network suggested that the upregulation of miR-34a in CRC proceeds via a TLR2/TLR4-dependent response to F. nucleatum. Finally, KRAS mutations were more frequently observed in CRC samples infected with F. nucleatum and were associated with greater expression of miR-21 in CRA, while IL8 was upregulated in MSI-high CRC.

Our findings indicate that F. nucleatum is a risk factor for CRC by increasing the expression of inflammatory mediators through a possible miRNA-mediated activation of TLR2/TLR4.

Core tip: We examined the influence of Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) in colorectal adenoma (CRA) and colorectal cancer (CRC) on the mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators and the association with microRNA (miRNA) levels, KRAS mutation, and microsatellite instability (MSI). We suggest that F. nucleatum contributes to CRC development by increasing the expression of inflammatory mediators through a possible miRNA-mediated activation of TLR2/TLR4. The miRNA:mRNA interaction network suggests an upregulation of miR-34a in CRC via a TLR2/TLR4-dependent response to F. nucleatum. KRAS mutations were more frequent in F. nucleatum-infected CRC and were associated with a greater expression of miR-21 in CRA, while IL8 was upregulated in MSI-high CRC.

- Citation: Proença MA, Biselli JM, Succi M, Severino FE, Berardinelli GN, Caetano A, Reis RM, Hughes DJ, Silva AE. Relationship between Fusobacterium nucleatum, inflammatory mediators and microRNAs in colorectal carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(47): 5351-5365

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i47/5351.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5351

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the three leading causes of cancer-related deaths and the third most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, with 1849518 new cases and 880792 deaths estimated in 2018[1]. In Brazil, CRC is the third most frequent cancer in men and the second most frequent cancer in women[2]. CRC is associated with chronic inflammation and oxidative processes that can induce malignant cell transformation and activate carcinogenic processes such as proliferation and angiogenesis[3].

The human intestinal microbiota is composed of many species that may play an important role in inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and CRC. Among the microbiota, Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) has emerged as a potential factor in CRC aetiology[4-7]. This bacterium is a gram-negative anaerobic commensal pathogen that is associated with several human diseases, especially those related to the oral and intestinal tracts[5,8]. Some studies suggest that F. nucleatum can cause a pro-inflammatory microenvironment in the intestine through deregulating inflammatory and immune responses, thereby promoting a microenvironment propitious for tumour initiation and CRC progression[5,6,9]. However, the mechanisms involved in this proposed tumourigenic process are still under discussion.

Studies have shown an abundance of F. nucleatum in tumour tissues and stool samples from CRC patients compared to adjacent normal tissues, colorectal adenomas (CRA) or even healthy subjects, and this observation was also correlated with shorter post-diagnosis overall survival[6,10-12]. These results reinforce the importance of F. nucleatum detection to assist in the identification of risk groups and early detection of CRC with implications for disease prognosis as well.

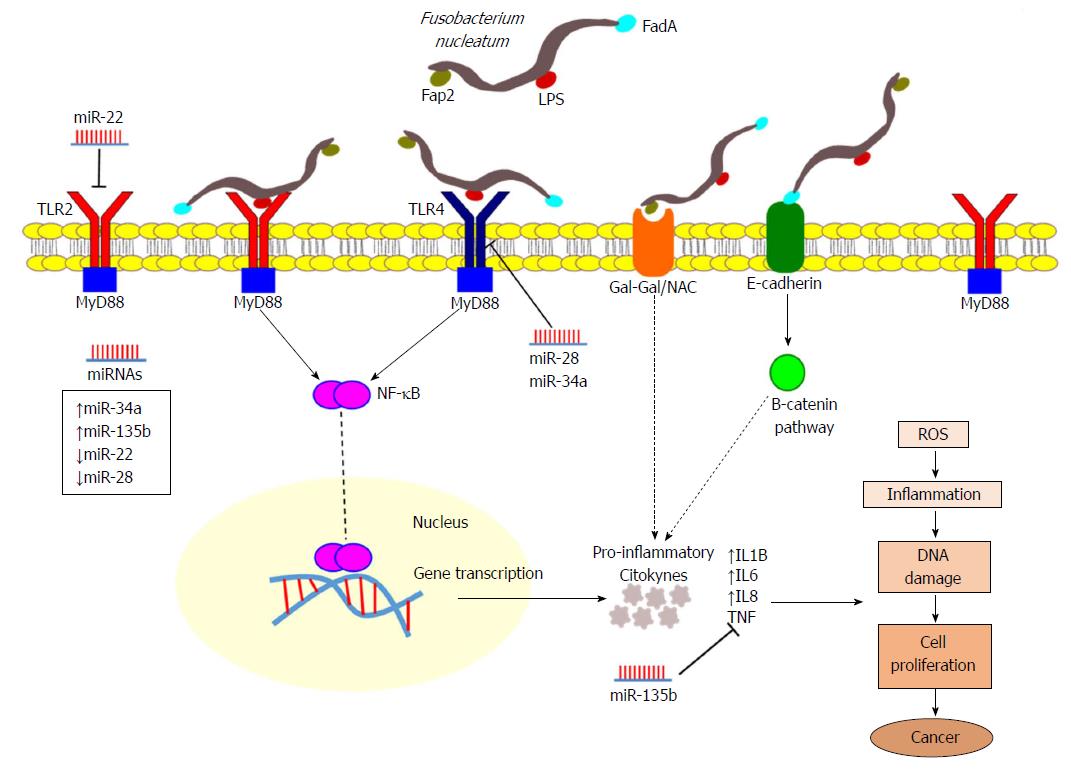

The interaction of microorganisms with the intestinal epithelium initially involves recognition by Toll-like receptors (TLRs)[13] and activation of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, which is the main signalling pathway regulating inflammatory responses implicated in colorectal tumourigenesis[14]. NF-κB may facilitate tumour progression through the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines[15], which have different roles in colorectal carcinogenesis. These pro-inflammatory cytokines include interleukin (IL) IL1B, which can induce tumour cell proliferation[16]; IL6 and IL8, which are related to tumour growth, angiogenesis and metastasis[17]; and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) A, which can decrease cell death[16,18].

F. nucleatum infection has also been associated with common CRC tumour genetic and epigenetic alterations, such as microsatellite instability (MSI), CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), and mutations in the BRAF and KRAS genes[19-21]. These alterations are thought to be due to F. nucleatum-mediated inflammatory responses influencing the molecular pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis via generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and greater pro-inflammatory gene expression, resulting in aberrant DNA methylation and DNA damage.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have a well-established role in inflammatory processes and can serve as molecular markers for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response[22]. Several miRNAs have been associated with CRC development and progression[23-25], including investigations of F. nucleatum-induced inflammation and CRC[26-28].

However, the interaction and (dys)regulation between inflammatory genes and miRNAs in potential F. nucleatum-induced colorectal carcinogenesis has not previously been elucidated. Thus, we investigated the association of F. nucleatum abundance in CRA and CRC tissues with the expression of inflammatory genes (TLR2, TLR4, NFKB1, TNF, IL1B, IL6 and IL8) and miRNAs (miR-21-3p, miR-22 -3p, miR-28-5p, miR-34a-5p and miR-135b-5p). These genes and miRNAs were selected due to their proposed involvement in the inflammatory process or colorectal carcinogenesis from the literature and public databases (TarBase v7.0 and miRBase 2.1)[29,30]. Our findings suggest that the host inflammatory response to F. nucleatum contributes to the neoplastic progression of CRA to CRC though TLR2 and TLR4 activation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL1B, IL6 and IL8 in a potentially miRNA-dependent process.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of IBILCE/UNESP, São José do Rio Preto (SP), Brazil (reference 1.452.373). Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals, and all samples were coded to protect patient anonymity.

A total of 43 fresh-frozen CRC tissue samples and the matched adjacent normal tissue (N-CRC) as well as 27 CRA tissue samples and the matched adjacent normal tissue (N-CRA) were collected from the Proctology Service of Hospital de Base and Endoscopy Center Rio Preto, both in SP (Brazil) during the period of 2010 to 2012.

All required information on demographic and clinical histopathological parameters was obtained from the patients’ medical records. The inclusion criteria were patients with a confirmed diagnosis of pre-cancerous adenomas or sporadic CRC by standard clinical histopathological measures without previous chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and the exclusion criterion was patients with hereditary CRC.

Simultaneous extraction of total RNA and DNA from colorectal tissue samples was performed using the TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA, United States) and corresponding protocol from the manufacturer. A reverse transcriptase reaction was performed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) as described previously[31]. The synthesis of cDNA to the miRNAs was carried out with a TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantification of F. nucleatum was performed in CRA, CRC and the respective adjacent normal DNA samples by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) with specific probes for the bacterial gene target NusG (5’-TCAGCAACTTGTCCTTCTTGATCTTTAAATGAACC-3’ TAMRA probe FAM) and the human gene PGT (5’-CCATCCATGTCCTCATCTC-3’ TAMRA probe FAM) as a reference were assayed by StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). The reactions were performed separately for each gene at a 12 μL final volume using 20 ng of genomic DNA, 400 nmol/L primer (NusG sequences: 5’-CAACCATTACTTTAACTCTACCATGTTCA-3’ and 3’-GTTGACTTTACAGAAGGAGATTATGTAAAAATC-5’, PGT: 5’-ATCCCCAAAGCACCTGGTTT-3’ and 3’-AGAGGCCAAGATAGTCCTGGTAA-5’) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Califórnia, United States), 400 nmol/L probe and GoTaq probe 1 × qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, United States). The reaction was subjected to temperatures of 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, then 60 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 57 °C for 1 min[10]. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and all experiments had a no-template control that was used to confirm no contamination in samples. Cq (cycle quantification) values were calculated after adjusting the threshold by StepOne software (v. 2.2.2) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), and all samples with a resulting Cq value were considered positive. Relative quantification (RQ) for the F. nucleatum gene (NusG) was calculated based on the 2-ΔΔCt method[32] and was expressed for each group relative to the respective normal tissue samples both in an unpaired way, using the mean of adjacent normal samples as a calibrator for each group, and in a paired way, using the respective adjacent normal of each sample as its specific calibrator.

Relative quantifications for the expression of 7 inflammatory genes [TLR2 (Hs00610101_m1), TLR4 (Hs01060206_m1), NFKB1 (Hs00765730_m1), IL1B (Hs01555410_m1), IL6 (Hs00985639_m1), IL8 (Hs00174103_m1) and TNF (Hs00174128_m1)] and 5 miRNAs [hsa-miR-21-3p (TM002438), hsa-miR-22-3p (TM000398), hsa-miR-28-5p (TM000411), hsa-miR-34a-5p (TM000426), and hsa-miR-135b-5p (TM002261)] were performed in 27 CRA and 43 CRC cDNA samples. Adjacent normal tissue samples of each lesion (CRA and CRC) were studied as a sample pool with the same amount of cDNA. The qPCRs were performed using the TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) with specific probes for each gene according to the instructions from the manufacturer, in a final volume of 10 μL using 25 ng of cDNA for the cytokine genes and 0.66 ng for the miRNAs. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and all experiments had a no-template control. The reactions were subjected to the StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). Cq values were calculated after adjusting the threshold by the StepOne software (v.2.2.2) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). For the mRNA analyses, the ACTB and GAPDH genes were used as reference genes, as validated in a previous study[31]. For the miRNA analysis, the method of global normalization was employed[33]. RQ values were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method[32], considering the pool of the respective adjacent normal samples as the calibrator and considering the Cq mean of CRA expression for the CRC samples.

Prediction of targets regulated by miRNAs was performed using the miRNA Data Integration Portal bioinformatics tool (http://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/)[34]. A protein-protein interaction network was generated via the String database (version 9.1) using the target genes as an input[35]. The identified miRNAs and target genes were integrated into interaction networks by Cytoscape software (version 3.1.1)[36]. The biological function of the identified genes in the network was defined using the BiNGO tool in Cytoscape (version 3.0.2)[37]. Cytoscape software also provides a graphical visualization of the network with the nodes representing the genes, miRNAs, and/or proteins and the edges representing their interactions.

KRAS (codons 12 and 13) hotspot mutation regions were analysed by PCR, followed by direct sequencing, as previously described[38]. PCR was performed at a final volume of 15 μL under the following conditions: 1.5 μL of buffer (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands), 2 mmol/L MgCl2 (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands), 100 mmol/L dNTPs (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Califórnia, United States), forward and reverse primers at 0.2 mmol/L (Sigma Aldrich), 1 unit of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) and 1 μL of DNA at 50 ng/μL. The KRAS primers used were 5’-GTGTGACATGTTCTAATATAGTCA-3’ (forward) and 3’-GAATGGTCCTGCACCAGTAA-5’ (reverse)[39].

PCR products were purified with ExoSAP (GE Technology, IL, United States) and then added to a sequencing reaction mix containing 1 μL of BigDye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), 1.5 μL of sequencing buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) and 1 μL of primer, followed by post-sequencing purification with a BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) according to the instructions from the manufacturer. Direct sequencing was performed on a 3500 xL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). All mutations were confirmed in a second, independent PCR experiment.

MSI evaluation was performed using a multiplex PCR comprising six quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeat markers (NR-27, NR-21, NR-24, BAT-25, BAT-26 and HSP110), as previously described[40,41]. Primer sequences, as described[41,42], were each reverse primer end-labelled with a fluorescent dye as follows: 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) for BAT-26 and NR-21; 20-chloro-70-phenyl-1,4-dichloro-6-carboxyfluorescein (VIC) for BAT-25, NR-27 and HSP110; and 2,7,8-benzo-5-fluoro-2,4,7-trichloro-5-carboxyfluorescein (NED) for NR-24. PCR was performed using a Qiagen Multiplex PCR Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) with 0.5 μL of DNA at 50 ng/μL and the following thermocycling conditions: 15 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 90 s and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 60 min. Fragment analyses were performed on a 3500 xL Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) according to the instructions from the manufacturer, and the results were analysed using GeneMapper v4.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). Cases exhibiting instability at two or more markers were considered to have high MSI (MSI-H), cases with instability at one marker were defined as having low MSI (MSI-L) and cases that showed no instability were defined as microsatellite stable (MSS)[40].

KRAS mutation and MSI status were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test. The distribution of continuous data was evaluated using the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test the significance of the RQ of the measured genes from the qPCR experiments. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient test was performed to compare the F. nucleatum quantification with the expression of the inflammatory genes and miRNAs. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism software (version 6.01).

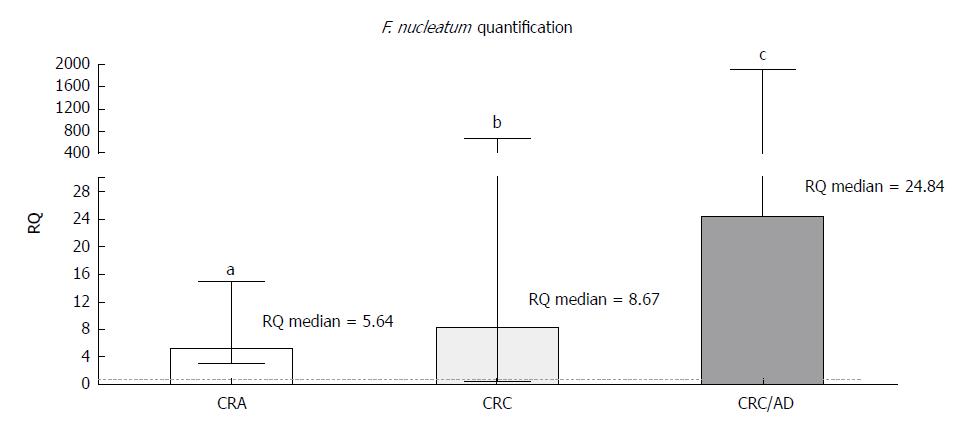

Among 43 CRC and 27 CRA samples and their respective normal adjacent mucosa (N-CRC and N-CRA, respectively) quantified for F. nucleatum, 33 (76.7%) CRC samples, 31 (72.1%) N-CRC samples, 14 (51.8%) CRA samples, and 13 (48.1%) N-CRA samples were positive for bacterial DNA. Of these samples, the presence of the bacterium was observed in both the lesion and its matched normal mucosa for 6 CRA samples and 27 CRC samples. A significant increase in bacterial DNA was found for both CRA (RQ = 5.64) and CRC (RQ = 8.67) tissues compared to the respective normal adjacent tissues (Figure 1).

In addition, the analysis of F. nucleatum quantification for the CRC group was also performed in a paired way, using the respective adjacent normal tissue of each sample as its specific calibrator. This result was consistent with the unpaired analysis showing more F. nucleatum in tumour tissues (RQ = 17.71, P = 0.0002). For the CRA samples, this paired analysis was not performed due to the low potential of analysing the available 6 paired samples.

A comparison of CRC samples with CRA samples, using the Cq mean of CRA rather than the normal mucosa as a calibrator for the analysis, estimated the quantification of F. nucleatum as 24.84 times greater in CRC samples than in CRA samples (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

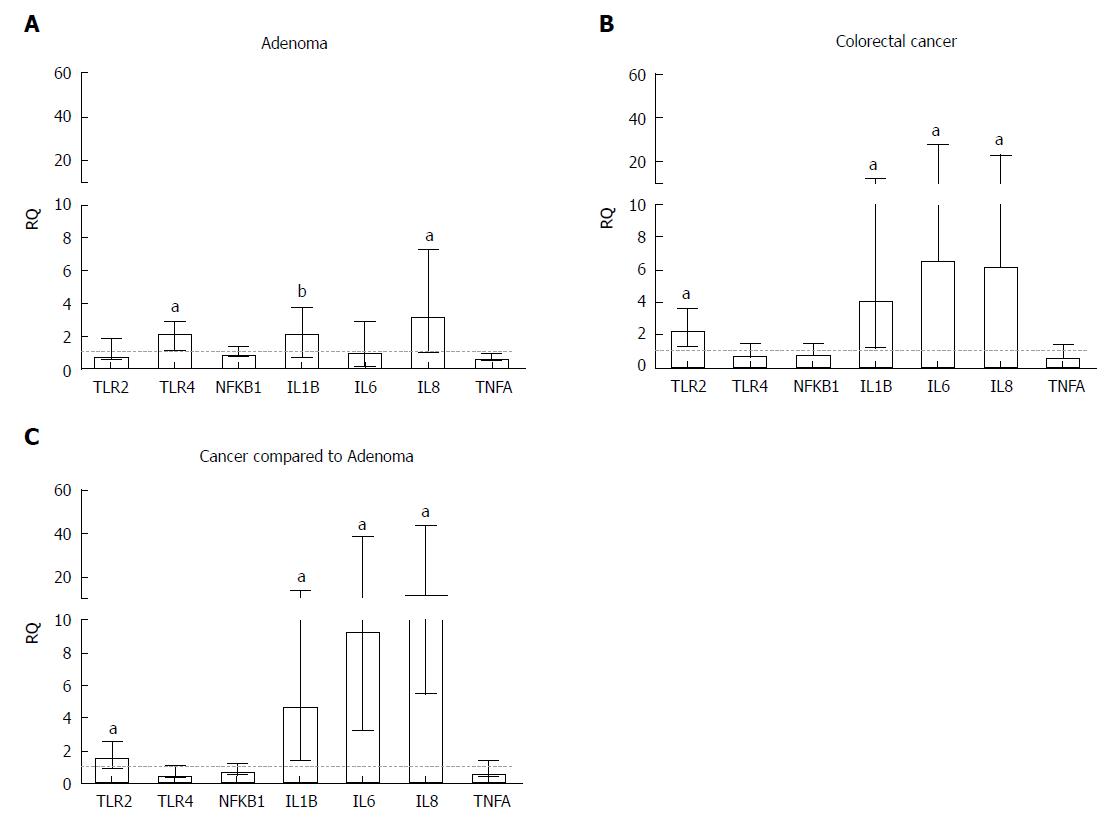

Gene expression of inflammatory mediators in CRA samples and CRC samples relative to adjacent normal tissue samples showed significantly increased mRNA levels for TLR4 (RQ = 2.27, P =0.0003), IL1B (RQ = 2.27, P = 0.0047) and IL8 (RQ = 3.33, P = 0.0006) in CRA tissues (Table 1, Figure 2A) and for TLR2 (RQ = 2.36, P < 0.0001), IL1B (RQ = 4.13, P < 0.0001), IL6 (RQ = 6.67, P < 0.0001) and IL8 (RQ = 6.36, P < 0.0001) in CRC tumours (Table 1, Figure 2B).

| TLR2 | TLR4 | NFKB1 | IL1B | IL6 | IL8 | TNF | |

| CRA | |||||||

| RQ median | 0.87 | 2.27 | 1.02 | 2.27 | 1.12 | 3.33 | 0.75 |

| RQ Range | 0.36-10.80 | 0.32-11.25 | 0.45-3.38 | 0.14-76.76 | 0.09-80.41 | 0.10-874.50 | 0.14-2.60 |

| P value | 0.2940 | 0.0003a | 0.5360 | 0.0047a | 0.2473 | 0.0006a | 0.0527 |

| CRC | |||||||

| RQ median | 2.36 | 0.74 | 0.90 | 4.13 | 6.67 | 6.36 | 0.72 |

| RQ Range | 0.31-35.80 | 0.20-23.42 | 0.31-8.49 | 0.13-245.70 | 0.09-192.80 | 0.16-194.20 | 0.06-31.76 |

| P value | < 0.0001a | 0.4476 | 0.9855 | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | 0.2391 |

| CRC/CRA | |||||||

| RQ median | 1.68 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 4.79 | 9.40 | 12.14 | 0.70 |

| RQ Range | 0.22-25.49 | 0.15-17.22 | 0.27-7.35 | 0.15-284.80 | 0.13-271.80 | 0.31-370.60 | 0.06-30.77 |

| P value | < 0.0001a | 0.0608 | 0.1237 | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | 0.1560 |

Additionally, elevated expression of TLR2 (RQ = 1.68, P < 0.0001), IL1B (RQ = 4.79, P < 0.0001), IL6 (RQ = 9.40, P < 0.0001) and IL8 (RQ = 12.12, P < 0.0001) was observed in CRC tumours compared to CRA tissues (Table 1, Figure 2C).

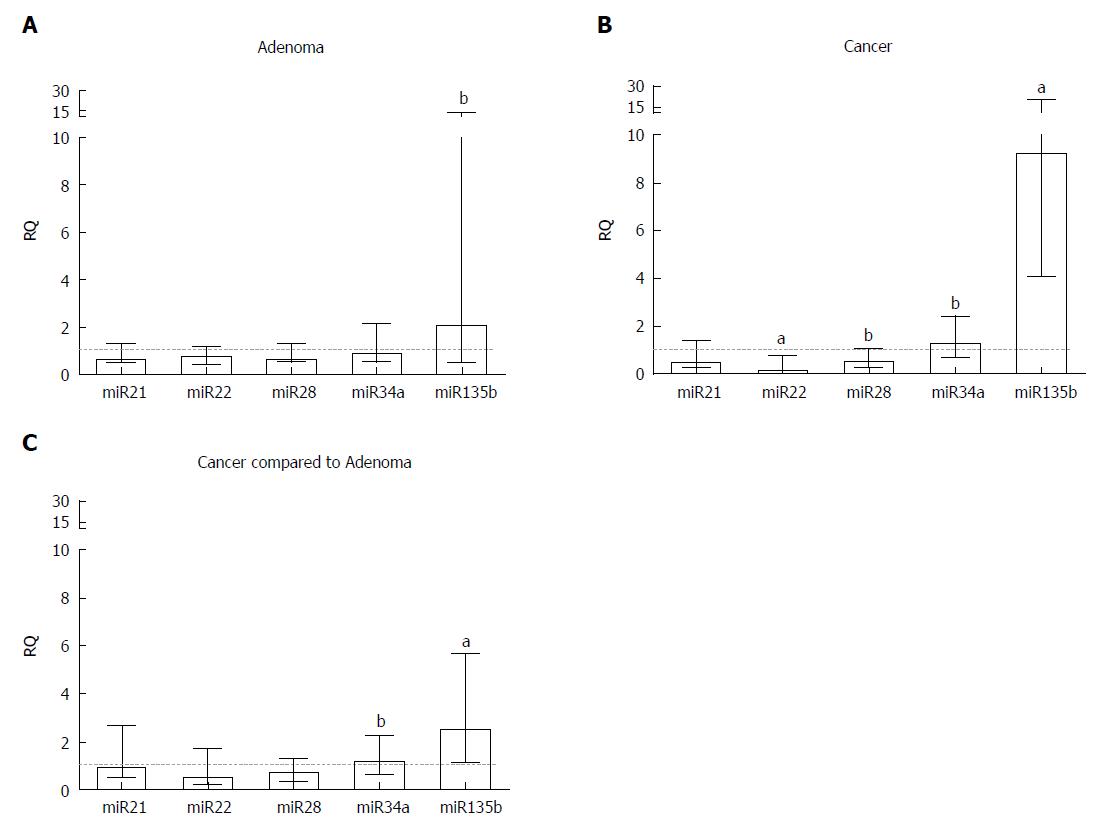

A similar estimation of miRNA relative gene expression was performed for CRA and CRC samples, in which miRNAs (miR-21, miR-22, miR-28, miR-34a, miR-135b) were quantified in each neoplastic tissue sample relative to a pool of the adjacent normal tissue. For the CRA group, only miR-135b was upregulated (RQ = 2.19, P = 0.0074) (Table 2, Figure 3A). However, for CRC samples, while miR-34a (RQ = 1.38, P = 0.0029) and miR-135b (RQ = 9.31, P < 0.0001) were upregulated, miR-22 (RQ = 0.27, P < 0.0001) and miR-28 (RQ = 0.65, P = 0.0045) were downregulated (Table 2, Figure 3B). Relative to the CRA group, CRC samples also presented a significant increase in the gene expression of miR-34a (RQ = 1.26, P = 0.01) and miR-135b (RQ = 2.64, P < 0.0001) (Table 2, Figure 3C).

| miR-21 | miR-22 | miR-28 | miR-34a | miR-135b | |

| CRA | |||||

| RQ median | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 2.19 |

| RQ Range | 0.15-13.91 | 0.10-3.05 | 0.08-2.17 | 0.12-4.74 | 0.10-25.13 |

| P value | 0.6349 | 0.1747 | 0.1904 | 0.3306 | 0.0074a |

| CRC | |||||

| RQ median | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.65 | 1.38 | 9.31 |

| RQ Range | 0.08-12.53 | 0.026-2.78 | 0.11-7.27 | 0.20-30.0 | 0.45-74.00 |

| P value | 0.1725 | < 0.0001a | 0.0045a | 0.0029a | < 0.0001a |

| CRC/CRA | |||||

| RQ median | 1.01 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 1.26 | 2.64 |

| RQ Range | 0.15-23.91 | 0.06-6.07 | 0.14-8.79 | 0.18-27.51 | 0.13-20.96 |

| P value | 0.0969 | 0.5770 | 0.1271 | 0.0101a | < 0.0001a |

A correlation analysis was performed between the RQ values of inflammatory genes (TLR2, TLR4, NFKB1, TNF, IL1B, IL6 and IL8) and F. nucleatum DNA levels in all neoplasms. For the CRA group, the only significant finding was a negative correlation between TLR4 and F. nucleatum quantification (r = - 0.62, P = 0.0235). However, for CRC, significant positive correlations were observed for bacterial DNA levels with cytokines IL1B (r = 0.46, P = 0.0066), IL6 (r = 0.47, P = 0.0059), and IL8 (r = 0.54, P = 0.0013) (Table 3).

| Spearman correlation coefficient (r) | CRA | CRC |

| TLR2 | 0.42 | 0.09 |

| P value | 0.1557 | 0.6335 |

| TLR4 | -0.62 | -0.01 |

| P value | 0.0235a | 0.9587 |

| NFKB1 | -0.40 | -0.04 |

| P value | 0.1809 | 0.8045 |

| IL1B | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| P value | 0.3064 | 0.0066a |

| IL6 | 0.01 | 0.47 |

| P value | 0.9716 | 0.0059a |

| IL8 | -0.07 | 0.54 |

| P value | 0.8166 | 0.0013a |

| TNF | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| P value | 0.3156 | 0.2027 |

| miR-21 | -0.21 | 0.26 |

| P value | 0.4643 | 0.1467 |

| miR-22 | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| P value | 0.5528 | 0.0331a |

| miR-28 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| P value | 0.8872 | 0.9413 |

| miR-34a | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| P value | 0.5630 | 0.9905 |

| miR-135b | -0.05 | 0.22 |

| P value | 0.8637 | 0.2163 |

In the miRNA analysis, while no significant correlations was observed for the CRA group, there was a significant positive correlation between miR-22 expression and F. nucleatum (r = 0.38, P = 0.0331) in the CRC group (Table 3).

Finally, independent of considerations of F. nucleatum levels, we also performed a correlation analysis between the RQ values of miRNAs and inflammatory genes in both CRA and CRC samples. For CRA samples, there was a positive correlation of IL8 with miR-21 (r = 0.40, P = 0.0466), miR-34a (r = 0.44, P = 0.0296) and miR-135b (r = 0.46, P = 0.0200) (Table 4). Regarding CRC, several positive correlations were observed between miR-21, miR-22, and miR-28 and most of the inflammatory genes evaluated, and there was also a significant inverse correlation between miR-135b and TNF (r = - 0.32, P = 0.0411) (Table 4).

| Spearman correlation coefficient (r) | miR-21 | miR-22 | miR-28 | miR-34a | miR-135b |

| CRA | |||||

| TLR2 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.09 |

| P value | 0.6608 | 0.1655 | 0.1266 | 0.2606 | 0.6714 |

| TLR4 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.38 |

| P value | 0.3892 | 0.7926 | 0.3955 | 0.0431 | 0.0598 |

| NFKB1 | -0.01 | -0.17 | -0.21 | -0.19 | -0.20 |

| P value | 0.9796 | 0.4252 | 0.3191 | 0.3650 | 0.3454 |

| IL1B | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.38 |

| P value | 0.1667 | 0.4834 | 0.6555 | 0.0232 | 0.0610 |

| IL6 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| P value | 0.1430 | 0.7148 | 0.8237 | 0.2136 | 0.2417 |

| IL8 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.44 | 0.46 |

| P value | 0.0466a | 0.4017 | 0.4273 | 0.0296a | 0.0200a |

| TNF | -0.21 | -0.04 | -0.03 | -0.05 | -0.11 |

| P value | 0.3083 | 0.8638 | 0.9012 | 0.8152 | 0.6084 |

| CRC | |||||

| TLR2 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.19 | -0.14 |

| P value | 0.0777 | 0.0005a | 0.2790 | 0.2408 | 0.3923 |

| TLR4 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.05 |

| P value | 0.668 | 0.0377a | 0.0401a | 0.1216 | 0.7586 |

| NFKB1 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.02 | -0.10 | -0.30 |

| P value | 0.2779 | 0.0499a | 0.8958 | 0.5462 | 0.0574 |

| IL1B | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.22 | -0.10 |

| P value | 0.0004a | 0.0055a | 0.4139 | 0.1668 | 0.5248 |

| IL6 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| P value | 0.0004a | 0.0002a | 0.2813 | 0.2095 | 0.7680 |

| IL8 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.13 |

| P value | 0.0005a | 0.0180a | 0.5734 | 0.1506 | 0.4314 |

| TNF | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.08 | -0.32 |

| P value | 0.1094 | 0.0071a | 0.8406 | 0.6264 | 0.0411a |

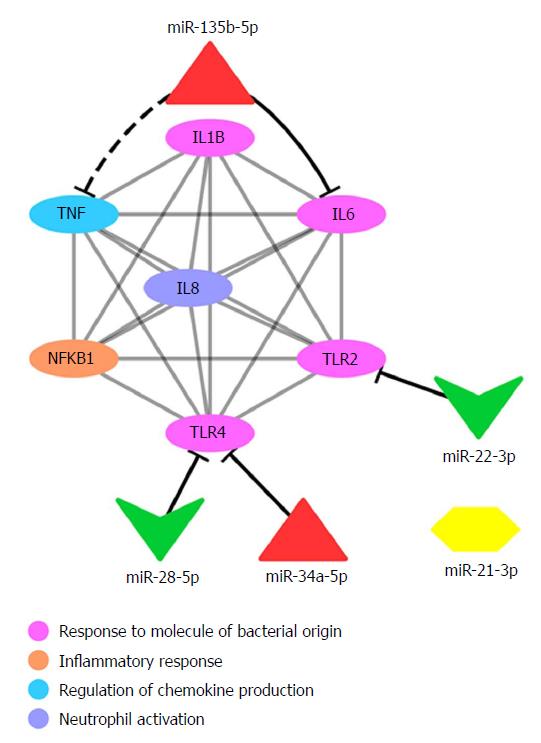

Additionally, we identified in silico a miRNA:mRNA interaction network that may be deregulated in CRC (Figure 4). This analysis demonstrated the interrelations of the inflammatory mediator genes alone and with their miRNA moderators (e.g., miR-28 and miR-34a targeting TLR4, miR-22 targeting TLR2 and miR-135b targeting IL6). The negative correlation of the expression of miR-135b and TNF found in this study (Table 4) was also demonstrated in this in silico a miRNA:mRNA interaction network, although not functionally validated in our study and not yet predicted by public databases[34] (Figure 4).

Mutations in codons 12 and 13 of the KRAS gene were detected in 8/27 (30%) of CRA tissues and 11/43 (26%) of CRC tissues (P = 0.7854), of which p.Gly12Asp (G12D) and p.Gly13Asp (G13D) were the most frequent changes in both CRA and CRC tissues (Table 5). Regarding the MSI status, all the CRAs were microsatellite stable or MSI-low, while 7/43 (16%) of CRC samples were MSI-high (P = 0.0382; Table 5). The KRAS mutation was associated with F. nucleatum presence in CRC tumours (P = 0.0432) and had greater expression of miR-21 in CRA samples (P = 0.0409). The MSI-high tumour status was associated with increased expression of IL8 (P = 0.0171). Other comparisons of the association between KRAS mutations and MSI status with F. nucleatum levels or cytokine gene and miRNA expressions showed no significant differences.

| KRAS status/mutation type | CRA, n = 27 (%) | CRC, n = 43 (%) | P value |

| WT | 19 (70.4) | 32 (74.5) | 0.7854 |

| Mutation | 8 | 11 | |

| p.Gly12Ala (G12A) | 1 (3.7) | 0 | |

| p.Gly12Ser (G12S) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | |

| p.Gly12Val (G12V) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (4.6) | |

| p.Gly12Asp (G12D) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (9.3) | |

| p.Gly13Asp (G13D) | 2 (7.4) | 4 (9.3) | |

| MSI status | |||

| MSS + MSI-L | 25 + 2 (100) | 34 + 2 (83.7) | 0.0382a |

| MSI-H | 0 | 7 (16.3) |

To better understand the possible mechanistic relationship between F. nucleatum presence and the immune response in CRC development, we evaluated the association between F. nucleatum quantification and the expression of cytokines and miRNAs involved in the inflammatory stress response in CRA and CRC tissues from a South American patient study. Our results corroborated previous studies showing that F. nucleatum is present in greater amounts in tumours compared to both CRA and matched normal tissues. Importantly, our work further suggests that the abundance of F. nucleatum can affect cytokine expression possibly via recognition by TLR4 and TLR2 with regulation by miRNAs such as miR-34a, miR-135b and miR-22.

Several studies in North American, European and Asian populations showed the overabundance of F. nucleatum when comparing CRC tissues with normal adjacent tissues, healthy subjects[5,10,11,37,40,43-45] or CRA tissues[10,43]. A recent meta-analysis concluded that intestinal F. nucleatum is a valuable diagnostic marker for CRC[46]. A different Brazilian study with a small sample size, also in the southeast region, previously showed greater levels of F. nucleatum in CRC (DNA levels in faecal samples of CRC patients were compared to those of healthy subjects)[47]. Our study of fresh tissue samples from Brazilian CRA and CRC patients provided more evidence of the increasing abundance of F. nucleatum in the progression from adenoma to cancer.

The mechanism by which F. nucleatum functionally contributes to colorectal tumourigenesis has been investigated in several studies. It has been shown that this bacterium causes an inflammatory microenvironment more favourable to CRC development among other bacteria that colonize at the tumour site[6]. A carcinogenic mechanism proposed is that F. nucleatum promotes an oncogenic and inflammatory response via FadA, the main virulence factor of F. nucleatum, binding to E-cadherin and activating the B-catenin pathway[48]. In addition, the F. nucleatum lectin Fap2 binds to the Gal-GalNAc polysaccharide expressed by CRC cells, likely increasing immune-mediated inflammation[9]. Moreover, the presence of F. nucleatum in the gut affects tumour-related cytokines and activates the JAK/STAT and MAPK/ERK pathways involved in CRC tumour progression[49] (Figure 5).

In our study, in CRA disease tissues, we found that the mRNA expression of TLR4, IL1B, and IL8 was increased, as was the expression of miR-135b. In CRC tumour tissues, the TLR2 receptor and the IL genes IL1B, IL6 and IL8 were significantly upregulated when compared to adjacent normal tissues and to CRA tissues. miRNA levels of miR-34a and miR-135b were more highly expressed in CRC tumours, while miR-22 and miR-28 were downregulated (Figure 5). These findings indicate that several of these genes are already dysregulated in early CRA stages of colorectal neoplasia as well as in CRC; thus, these genes may contribute to inflammatory stresses that drive the progression from CRA to CRC. Greater TLR2 expression appears to be a later event in colorectal carcinogenesis, as also indicated by our recent study showing increased mRNA and protein expression of TLR2 in CRC tissues[31].

Recent studies have demonstrated that the TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB pathway is activated by F. nucleatum infection, which stimulates the overexpression of miR-21[28]. Moreover, the TLR4/MYD88 innate immune signalling and the miR-18a and miR-4802 expression in CRC patients with a high amount of F. nucleatum activate the autophagy pathway to control CRC chemoresistance[50]. In summary, these findings suggest the involvement of both TLR2 and TLR4 in F. nucleatum immune recognition.

Correlations of both inflammatory genes and miRNA expression with F. nucleatum levels showed positive associations with IL1B, IL6, and IL8 as well as with miR-22 in CRC tissues. Increased expression of IL1B, IL6 and TNF has also been reported by in vitro and animal model studies after F. nucleatum infection[51,52].

Together with existing data, our results are consistent with a scenario in which F. nucleatum triggers an increased expression of IL1B, IL6 and IL8, which further adds to inflammatory pressures fuelling the progression of colorectal neoplasia. Our work suggests that this phenomenon may proceed by an alternative pathway involving the recognition by the TLR2 receptor (Figure 5) to that pathway previously shown for the invasion of epithelial cells via FadA[48].

To date, several studies evaluated the abundance of F. nucleatum with miRNA expression in CRC[26-28]. In our study, we found a positive correlation between miR-22 and the abundance of F. nucleatum in CRC. miR-22 suppresses the expression of the p38 gene, which can impair the production of dendritic cells in tumours[53]. As dendritic cells are important in the TLR-mediated recognition of microorganisms[54], patients with upregulated miR-22 may have a compromised immune system due to fewer dendritic cells, favouring the proliferation of microorganisms such as F. nucleatum. Therefore, this positive correlation observed between miR-22 and F. nucleatum levels may be related to its role in the immune response and should be further investigated.

In addition, we also observed associations between both the KRAS mutation and MSI status and the expression of inflammatory genes or miRNAs in CRA and CRC tissues. Interestingly, we observed a greater expression of miR-21 associated with the KRAS mutation in the CRA tissues, but not in CRC tissues. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the overexpression of wild type KRAS or mutated KRAS (G12D) was reported to modulate the expression of miRNAs, including miR-21 and miR-30c[55]. The authors showed that miR-30c and miR-21 were specifically activated by KRAS and played an important role in lung cancer development and chemoresistance by targeting crucial tumour suppressor genes. Moreover, we also observed a positive association between the expression of IL8 mRNA and MSI-H colorectal carcinoma, independent of the presence and abundance of F. nucleatum. Recently, Hamada et al[20] reported an association of F. nucleatum levels with the immune response to colorectal carcinoma according to the tumour MSI status, suggesting an interplay between F. nucleatum, MSI status, and immune cells in the CRC tumour microenvironment. MSI-H colorectal carcinomas generate immunogenic peptides due to a mismatch repair deficiency, resulting in a strong anti-tumour immune response thought to underlie the reported favourable prognosis and better response to immunotherapies of this molecular subtype of CRC[20].

We also evaluated the correlation between the expression of miRNAs and inflammatory mediator genes, and we formulated a miRNA:mRNA interaction network based on predicted database targets[34]. The correlations were mainly positive, including miR-21, miR-34a and miR-135b with IL8 in CRA tissues and between miR-21, miR-22 and miR-28 with most of the inflammatory mediator genes studied in CRC tissues. However, a negative correlation was observed between miR-135b and TNF.

miR-135b has been previously associated with an increased expression in CRC and CRA tissues[56-58] and has been proposed to be an oncomiR targeting several tumour suppressor genes[56,58]. Studies have proposed that the detection of miR-135b in stool samples can be used as a non-invasive biomarker for CRC and CRA[59], and silencing miR-135b may be considered a possible therapy for CRC[56,58]. Data showing that miR-135b indirectly inhibits the production of LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-induced TNF by suppressing the production of ROS and the activation of NF-κB in human macrophages[60] support the negative correlation found between miR-135b and TNF in this study. Although this proposed miRNA-mRNA relationship is not yet predicted by the major miRNA public databases[34], TNF may have an indirect immune regulation by miR-135b.

Regarding the role of miR-34a in CRC, studies demonstrated that it acts as both an oncomiR that is upregulated[61,62] and as a tumour suppressor that displays reduced expression[63-66]. According to our miRNA:mRNA interaction network analysis, miR-34a can target TLR4 (Figure 4). This may explain the low expression of TLR4 in CRC samples and overexpression in CRA samples, in which miR-34a had basal expression. Our data, together with that of previous studies, showed an increased expression of TLR2 in CRC samples. Therefore, in CRC, a significant mechanism for the recognition of F. nucleatum may operate via TLR2, with consequent activation of ILs IL1B, IL6 and IL8 via NF-κB. Moreover, TLR2 is a predicted target of miR-22, which was downregulated in the CRC samples evaluated in our study (Figure 5).

Evidence suggests that miR-22 and miR-28 function as tumour suppressors. miR-22 can target key oncogenes for tumour invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis in CRC[67,68]. A recent study showed reduced expression of miR-28 in the tissues of CRC liver metastases[69]. However, the activity of this miRNA differs by 3p or 5p strand translation. miR-28-3p has been implicated in increased tumour migration and invasion, while miR-28-5p, analysed in our study, was reported to play a role in reducing tumour proliferation, migration and invasion in CRC[70].

Our results showed a greater level of F. nucleatum in CRA and CRC tissues, which was more striking for CRC samples, suggesting an expansion of F. nucleatum colonization during the progression from adenoma to adenocarcinoma. Our gene expression data suggested that this phenomenon may lead to increased inflammatory pressures during CRC development based on the high expression of pro-inflammatory ILs IL1B, IL6 and IL8 and the correlation with F. nucleatum levels. Immune recognition of F. nucleatum may be mainly mediated by TLR2 and/or TLR4 and dependent on interactions with differently regulated miRNAs. Together, these findings provide further potential mechanistic rationale for the immune-comprised pro-inflammatory role of F. nucleatum in colorectal carcinogenesis. Efforts to develop early detection strategies for CRC could include these biological interactors as potential functional biomarkers of F. nucleatum-mediated disease in addition to overall measures of F. nucleatum levels.

Recently, Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum), an anaerobic bacterial component of the oral and gut commensal flora, has emerged as a risk factor for colorectal cancer (CRC) development. Several studies have observed an association between overabundance of F. nucleatum in colonic tumor tissue compared to the normal matched mucosa. However, despite progress in this field the molecular mechanisms of how the bacterium etiologically contributes to carcinogenesis are still unclear.

We previously observed an association of the TLR2-196 to -174del genetic variant with increased CRC risk, together with an increased expression of TLR2 mRNA and protein in tumor tissues[31]. The major postulated mechanism of F. nucleatum-mediated colorectal tumorigenesis involves immune related inflammatory responses. Therefore, we decided to extend our previous work by measuring the transcript levels of important mediators in the pathogen-activated immune and inflammatory response, including TLR2 / TLR4 receptor and cytokine genes, and then evaluating the association of their expression with F. nucleatum levels in colorectal tumors. As microRNAs have been shown to be epigenetic regulators of inflammatory responses, we further examined the involvement of miRNAs in modulating the bacterial - cytokine interaction.

The main objective of this study was to investigate the association between inflammatory genes and F. nucleatum in colorectal carcinogenesis, by examining tissues from the major colorectal neoplasms of adenoma and adenocarcinomas. A secondary objective was to examine the interaction of the bacterial mediated immune response with microRNA (miRNA) regulation. The elucidation of likely mechanisms whereby F. nucleatum may contribute to inflammatory mediated colorectal carcinogenesis will help to better understand the molecular pathways activated by this bacterium and where prevention and treatment strategies can be best targeted.

Robust techniques were used for DNA quantification of F. nucleatum and RNA transcript measures of the inflammatory genes and miRNAs in normal and tumor tissues. For this purpose, we used TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) with specific probes for each gene and miRNA for relative quantification. The reactions were analyzed using the StepOnePlus real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). Mutation testing of the KRAS gene was performed by direct sequencing and microsatellite instability (MSI) evaluation was performed using a multiplex PCR. In addition, we also used a bioinformatic tool ‘miRNA Data Integration Portal’ (http://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/)[34] to build an miRNA:mRNA interaction network by using Cytoscape software (version 3.1.1)[36].

Ours results confirm the overabundance of F. nucleatum in adenoma and tumor neoplasms compared to their respective matched normal tissues, as previously found in several populations. We further suggest that this bacterial load increases the expression of TLR2 and TLR4 receptors and consequently of pro-inflammatory interleukins IL1B, IL6 and IL8. This immune-modulation of the inflammatory response to F. nucleatum colonic invasion also affects the expression of miRNA regulators of the inflammatory response. In particular, these miRNA:mRNA interactions network indicate a mechanism of colorectal carcinogenesis where altered expression of miR-34a, miR-135b, and miR-22, previously associated with CRC, occurs via a TLR2/TLR4 dependent response to F. nucleatum. In analyses stratified by tumor molecular characteristics, we observed that KRAS was more frequently mutated in tumors with F. nucleatum, and that an increased IL-8 expression was associated with MSI-high status. Therefore, more studies of gene function and regulation within the inflammatory pathways impacted by F. nucleatum invasion are needed, along with consideration of tumor molecular subtypes.

Our findings reinforce the increasing invasion of F. nucleatum during the colorectal adenoma to cancer development. This appears to increase expression of pro-inflammatory mediators and dysregulation of miRNA expression, leading to a more carcinogenic microenvironment alongside genetic alterations such as KRAS mutation and MSI-high. Therefore, together with other studies, our results suggest that F. nucleatum is involved in CRC development through immune responses to inflammatory stresses. Further work is needed to functionally demonstrate these postulated tumorigenic mechanisms, and also for early CRC detection and diagnosis strategies using biomarkers of F. nucleatum presence or the consequent immune response.

The intestinal microbiota is very diverse and important for the maintenance of epitelial homeostasis. Disturbances of this microbiome balance appears to be a major factor in CRC etiology. F. nucleatum has been implicated in recent years, by in vitro and in mouse models, as a carcinogenic bacterium through generation of a microenvironment conducive to cancer development. Considering that F. nucleatum has been found to be highly abundant in both adenoma and CRC neoplasms, it may have uses as a tissue or non-invasive biomarker in faeces (or possibly mouth-rinse samples) for CRC and the early detection of adenomas (which may help define a higher risk group for CRC development due to the presences of the bacterium). However, further investigations are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms in the immuno-inflammatory response to the increased invasion of this bacterium into developing neoplasms, and if this can promote genetic and epigenetic alterations that may culminate in CRC development.

We thank Lucas Trevizani Rasmussen for kindly donating some miRNA probes. We are grateful to the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, NO. 2015/21464-0) for the support for English revision, the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for the doctoral scholarship, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, NO. 310120/2015-2) for the productivity research scholarship.

| 1. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2018; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3585] [Cited by in RCA: 5064] [Article Influence: 633.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Ministério da Saúde, Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva. Estimativa 2018 - Incidência de câncer no Brasil. 2018. Accessed October 24. 2018; Available from: http://www.inca.gov.br/estimativa/2018/index.asp. |

| 3. | Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, Hermoso MA. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:149185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1033] [Cited by in RCA: 1280] [Article Influence: 106.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leung A, Tsoi H, Yu J. Fusobacterium and Escherichia: models of colorectal cancer driven by microbiota and the utility of microbiota in colorectal cancer screening. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:651-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J, Barnes R, Watson P, Allen-Vercoe E, Moore RA. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22:299-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1164] [Cited by in RCA: 1577] [Article Influence: 105.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1659] [Cited by in RCA: 2063] [Article Influence: 158.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Shang FM, Liu HL. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: A review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10:71-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 8. | Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 55.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Liu Y, Baba Y, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Hiyoshi Y, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Wu R, Baba H. Progress in characterizing the linkage between Fusobacterium nucleatum and gastrointestinal cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2018; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Flanagan L, Schmid J, Ebert M, Soucek P, Kunicka T, Liska V, Bruha J, Neary P, Dezeeuw N, Tommasino M. Fusobacterium nucleatum associates with stages of colorectal neoplasia development, colorectal cancer and disease outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1381-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Li YY, Ge QX, Cao J, Zhou YJ, Du YL, Shen B, Wan YJ, Nie YQ. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum infection with colorectal cancer in Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3227-3233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hussan H, Clinton SK, Roberts K, Bailey MT. Fusobacterium’s link to colorectal neoplasia sequenced: A systematic review and future insights. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8626-8650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Marietta E, Rishi A, Taneja V. Immunogenetic control of the intestinal microbiota. Immunology. 2015;145:313-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sakamoto K, Maeda S. Targeting NF-kappaB for colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:593-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | de Koning HD, Simon A, Zeeuwen PL, Schalkwijk J. Pattern recognition receptors in infectious skin diseases. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:881-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koorts AM, Levay PF, Becker PJ, Viljoen M. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines during immune stimulation: modulation of iron status and red blood cell profile. Mediators Inflamm. 2011;2011:716301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morandini AC, Chaves Souza PP, Ramos-Junior ES, Brozoski DT, Sipert CR, Souza Costa CA, Santos CF. Toll-like receptor 2 knockdown modulates interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 but not stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) in human periodontal ligament and gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontol. 2013;84:535-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mager LF, Wasmer MH, Rau TT, Krebs P. Cytokine-Induced Modulation of Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2016;6:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mima K, Sukawa Y, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Yamauchi M, Inamura K, Kim SA, Masuda A, Nowak JA, Nosho K. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T Cells in Colorectal Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:653-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 53.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hamada T, Zhang X, Mima K, Bullman S, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Kosumi K, Masugi Y, Twombly TS, Cao Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer Relates to Immune Response Differentially by Tumor Microsatellite Instability Status. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1327-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Koi M, Okita Y, Carethers JM. Fusobacterium nucleatum Infection in Colorectal Cancer: Linking Inflammation, DNA Mismatch Repair and Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2018;2:37-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li X, Nie J, Mei Q, Han WD. MicroRNAs: Novel immunotherapeutic targets in colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5317-5331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Okayama H, Schetter AJ, Harris CC. MicroRNAs and inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of colon cancer. Dig Dis. 2012;30 Suppl 2:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mohammadi A, Mansoori B, Baradaran B. The role of microRNAs in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84:705-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Qu A, Yang Y, Zhang X, Wang W, Liu Y, Zheng G, Du L, Wang C. Development of a preoperative prediction nomogram for lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer based on a novel serum miRNA signature and CT scans. EBioMedicine. 2018; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ito M, Kanno S, Nosho K, Sukawa Y, Mitsuhashi K, Kurihara H, Igarashi H, Takahashi T, Tachibana M, Takahashi H. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with clinical and molecular features in colorectal serrated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1258-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nosho K, Sukawa Y, Adachi Y, Ito M, Mitsuhashi K, Kurihara H, Kanno S, Yamamoto I, Ishigami K, Igarashi H. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with immunity and molecular alterations in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:557-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 28. | Yang Y, Weng W, Peng J, Hong L, Yang L, Toiyama Y, Gao R, Liu M, Yin M, Pan C. Fusobacterium nucleatum Increases Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Cells and Tumor Development in Mice by Activating Toll-Like Receptor 4 Signaling to Nuclear Factor-κB, and Up-regulating Expression of MicroRNA-21. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:851-866.e24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 88.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Vlachos IS, Paraskevopoulou MD, Karagkouni D, Georgakilas G, Vergoulis T, Kanellos I, Anastasopoulos IL, Maniou S, Karathanou K, Kalfakakou D. DIANA-TarBase v7.0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D153-D159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 541] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D68-D73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3819] [Cited by in RCA: 3922] [Article Influence: 301.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Proença MA, de Oliveira JG, Cadamuro AC, Succi M, Netinho JG, Goloni-Bertolo EM, Pavarino ÉC, Silva AE. TLR2 and TLR4 polymorphisms influence mRNA and protein expression in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7730-7741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149116] [Cited by in RCA: 139463] [Article Influence: 5578.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 33. | Mestdagh P, Van Vlierberghe P, De Weer A, Muth D, Westermann F, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 745] [Cited by in RCA: 839] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Shirdel EA, Xie W, Mak TW, Jurisica I. NAViGaTing the micronome--using multiple microRNA prediction databases to identify signalling pathway-associated microRNAs. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808-D815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3099] [Cited by in RCA: 3424] [Article Influence: 263.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chen R, Mias GI, Li-Pook-Than J, Jiang L, Lam HY, Chen R, Miriami E, Karczewski KJ, Hariharan M, Dewey FE. Personal omics profiling reveals dynamic molecular and medical phenotypes. Cell. 2012;148:1293-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 916] [Cited by in RCA: 908] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448-3449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2998] [Cited by in RCA: 3164] [Article Influence: 150.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yamane LS, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Alvarenga L, Oliveira CZ, Berardinelli GN, Almodova E, Cunha TR, Fava G, Colaiacovo W, Melani A. KRAS and BRAF mutations and MSI status in precursor lesions of colorectal cancer detected by colonoscopy. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:1419-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Martinho O, Gouveia A, Viana-Pereira M, Silva P, Pimenta A, Reis RM, Lopes JM. Low frequency of MAP kinase pathway alterations in KIT and PDGFRA wild-type GISTs. Histopathology. 2009;55:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Campanella NC, Berardinelli GN, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Viana D, Palmero EI, Pereira R, Reis RM. Optimization of a pentaplex panel for MSI analysis without control DNA in a Brazilian population: correlation with ancestry markers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Berardinelli GN, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Durães R, Antônio de Oliveira M, Guimarães D, Reis RM. Advantage of HSP110 (T17) marker inclusion for microsatellite instability (MSI) detection in colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9:28691-28701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Buhard O, Cattaneo F, Wong YF, Yim SF, Friedman E, Flejou JF, Duval A, Hamelin R. Multipopulation analysis of polymorphisms in five mononucleotide repeats used to determine the microsatellite instability status of human tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:241-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mira-Pascual L, Cabrera-Rubio R, Ocon S, Costales P, Parra A, Suarez A, Moris F, Rodrigo L, Mira A, Collado MC. Microbial mucosal colonic shifts associated with the development of colorectal cancer reveal the presence of different bacterial and archaeal biomarkers. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:167-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wei Z, Cao S, Liu S, Yao Z, Sun T, Li Y, Li J, Zhang D, Zhou Y. Could gut microbiota serve as prognostic biomarker associated with colorectal cancer patients’ survival? A pilot study on relevant mechanism. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46158-46172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Repass J, Maherali N, Owen K; Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology; Reproducibility Project Cancer Biology. Registered report: Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Elife. 2016;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Peng BJ, Cao CY, Li W, Zhou YJ, Zhang Y, Nie YQ, Cao YW, Li YY. Diagnostic Performance of Intestinal Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131:1349-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Fukugaiti MH, Ignacio A, Fernandes MR, Ribeiro Júnior U, Nakano V, Avila-Campos MJ. High occurrence of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Clostridium difficile in the intestinal microbiota of colorectal carcinoma patients. Braz J Microbiol. 2015;46:1135-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Rubinstein MR, Wang X, Liu W, Hao Y, Cai G, Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:195-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1511] [Cited by in RCA: 1834] [Article Influence: 141.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 49. | Yu YN, Yu TC, Zhao HJ, Sun TT, Chen HM, Chen HY, An HF, Weng YR, Yu J, Li M. Berberine may rescue Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced colorectal tumorigenesis by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32013-32026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, Sun T, Ma D, Han J, Qian Y, Kryczek I, Sun D, Nagarsheth N. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell. 2017;170:548-563.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 814] [Cited by in RCA: 1630] [Article Influence: 181.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Velsko IM, Chukkapalli SS, Rivera-Kweh MF, Chen H, Zheng D, Bhattacharyya I, Gangula PR, Lucas AR, Kesavalu L. Fusobacterium nucleatum Alters Atherosclerosis Risk Factors and Enhances Inflammatory Markers with an Atheroprotective Immune Response in ApoE(null) Mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Martinho FC, Leite FR, Nóbrega LM, Endo MS, Nascimento GG, Darveau RP, Gomes BP. Comparison of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharides Clinically Isolated from Root Canal Infection in the Induction of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Secretion. Braz Dent J. 2016;27:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Liang Q, Chiu J, Chen Y, Huang Y, Higashimori A, Fang J, Brim H, Ashktorab H, Ng SC, Ng SSM. Fecal Bacteria Act as Novel Biomarkers for Noninvasive Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2061-2070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Legitimo A, Consolini R, Failli A, Orsini G, Spisni R. Dendritic cell defects in the colorectal cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:3224-3235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Shi L, Middleton J, Jeon YJ, Magee P, Veneziano D, Laganà A, Leong HS, Sahoo S, Fassan M, Booton R. KRAS induces lung tumorigenesis through microRNAs modulation. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Valeri N, Braconi C, Gasparini P, Murgia C, Lampis A, Paulus-Hock V, Hart JR, Ueno L, Grivennikov SI, Lovat F. MicroRNA-135b promotes cancer progression by acting as a downstream effector of oncogenic pathways in colon cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:469-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Wu W, Wang Z, Yang P, Yang J, Liang J, Chen Y, Wang H, Wei G, Ye S, Zhou Y. MicroRNA-135b regulates metastasis suppressor 1 expression and promotes migration and invasion in colorectal cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;388:249-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | He Y, Wang J, Wang J, Yung VY, Hsu E, Li A, Kang Q, Ma J, Han Q, Jin P. MicroRNA-135b regulates apoptosis and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by targeting large tumor suppressor kinase 2. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:1382-1395. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Wu CW, Ng SC, Dong Y, Tian L, Ng SS, Leung WW, Law WT, Yau TO, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Identification of microRNA-135b in stool as a potential noninvasive biomarker for colorectal cancer and adenoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2994-3002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Li P, Fan JB, Gao Y, Zhang M, Zhang L, Yang N, Zhao X. miR-135b-5p inhibits LPS-induced TNFα production via silencing AMPK phosphatase Ppm1e. Oncotarget. 2016;7:77978-77986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kara M, Yumrutas O, Ozcan O, Celik OI, Bozgeyik E, Bozgeyik I, Tasdemir S. Differential expressions of cancer-associated genes and their regulatory miRNAs in colorectal carcinoma. Gene. 2015;567:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Aherne ST, Madden SF, Hughes DJ, Pardini B, Naccarati A, Levy M, Vodicka P, Neary P, Dowling P, Clynes M. Circulating miRNAs miR-34a and miR-150 associated with colorectal cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Lai M, Du G, Shi R, Yao J, Yang G, Wei Y, Zhang D, Xu Z, Zhang R, Li Y. MiR-34a inhibits migration and invasion by regulating the SIRT1/p53 pathway in human SW480 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:3301-3307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Li C, Wang Y, Lu S, Zhang Z, Meng H, Liang L, Zhang Y, Song B. MiR-34a inhibits colon cancer proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting platelet-derived growth factor receptor α. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:7072-7078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Chandrasekaran KS, Sathyanarayanan A, Karunagaran D. Downregulation of HMGB1 by miR-34a is sufficient to suppress proliferation, migration and invasion of human cervical and colorectal cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:13155-13166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Almeida AL, Bernardes MV, Feitosa MR, Peria FM, Tirapelli DP, Rocha JJ, Feres O. Serological under expression of microRNA-21, microRNA-34a and microRNA-126 in colorectal cancer. Acta Cir Bras. 2016;31 Suppl 1:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Li B, Song Y, Liu TJ, Cui YB, Jiang Y, Xie ZS, Xie SL. miRNA-22 suppresses colon cancer cell migration and invasion by inhibiting the expression of T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1 and matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:1932-1938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Yamakuchi M, Yagi S, Ito T, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-22 regulates hypoxia signaling in colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Vychytilova-Faltejskova P, Pesta M, Radova L, Liska V, Daum O, Kala Z, Svoboda M, Kiss I, Slaby O. Genome-wide microRNA Expression Profiling in Primary Tumors and Matched Liver Metastasis of Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2016;13:311-316. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Almeida MI, Nicoloso MS, Zeng L, Ivan C, Spizzo R, Gafà R, Xiao L, Zhang X, Vannini I, Fanini F. Strand-specific miR-28-5p and miR-28-3p have distinct effects in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:886-896.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Li YY, Roncucci L S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y