Published online Sep 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4061

Peer-review started: July 17, 2018

First decision: July 31, 2018

Revised: August 2, 2018

Accepted: August 24, 2018

Article in press: August 24, 2018

Published online: September 21, 2018

Processing time: 65 Days and 11.3 Hours

To clarify the role of serum anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody titers in gastric cancer.

In this cross-sectional study, the effect of patients’ baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings on their serum antibody titers were assessed. We evaluated consecutive patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and their first evaluation for H. pylori infection using a serum antibody test. We excluded patients with a history of eradication therapy. The participants were divided into four groups according to their E-plate serum antibody titer. Patients with serum antibody titers < 3, 3-9.9, 10-49.9, and ≥ 50 U/mL were classified into groups A, B, C, and D, respectively.

In total, 874 participants were analyzed with 70%, 16%, 8.7%, and 5.1% of them in the groups A, B, C, and D, respectively. Patients in group C were older than patients in groups A and B. Gastric open-type atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds, diffuse redness, and duodenal ulcers were associated with a high titer. Regular arrangements of collecting venules, fundic gland polyps, superficial gastritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease were related to a low titer. Multivariate analysis revealed that nodularity (P = 0.0094), atrophy (P = 0.0076), and age 40-59 years (vs age ≥ 60 years, P = 0.0090) were correlated with a high serum antibody titer in H. pylori-infected patients. Intestinal metaplasia and atrophy were related to age ≥ 60 years in group C and D.

Serum antibody titer changes with age, reflects gastric mucosal inflammation, and is useful in predicting the risk of gastric cancer.

Core tip: A positive-low serum anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody titer (E-plate Eiken) (10-49.9 U/mL) and a negative-high titer (3-9.9 U/mL) are associated with intestinal-type gastric cancer. A positive-high titer (≥ 50 U/mL) correlates with diffuse-type gastric cancer. Few studies have reported on the relationship between the serum antibody titer and endoscopic findings. In H. pylori-infected patients, a high titer of serum antibody was associated with gastric nodularity and atrophy. In H. pylori-infected patients, the antibody titer decreased in patients aged 60 years. Intestinal metaplasia and gastric atrophy were related to age ≥ 60 years in patients with positive titers.

- Citation: Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Sakitani K, Yamakawa T, Takahashi Y, Yamamichi N, Hata K, Seto Y, Koike K, Watanabe H, Suzuki H. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody titer and its association with gastric nodularity, atrophy, and age: A cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(35): 4061-4068

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i35/4061.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4061

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is the main carcinogenic entity in the stomach, and eradicating it reduces the incidence of gastric cancer[1-5]. The 13C-urea breath test (UBT), serum immunoglobulin G anti-H. pylori antibodies, stool antigen test, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), rapid urease test, culture, and pathology are used in routine practice to diagnose H. pylori infection. UBT is the gold standard for diagnosing H. pylori infection because its accuracy is the best of all these tests[2,6]. However, UBT requires the patients to stop using proton pump inhibitors or antibiotics.

Other than UBT, measuring the serum antibody titer is useful because serum antibody testing is easy, inexpensive, and hardly affected by changes in the stomach[7]. Some serological tests are of high-quality, and measuring the antibody titer once in adults makes it possible to observe subsequent changes in it with time and diagnose H. pylori infection[8-11]. Serum antibody titer is useful to evaluate both new-onset and successful eradication of the disease[12]. Furthermore, serum antibody titer is associated with the risk of gastric cancer. For example, a high titer correlates with diffuse-type of gastric cancer according to Lauren’s classification. A positive-low titer and negative-high titer are associated with intestinal-type cancer[10,13-15]. An E-plate (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) is frequently used for commercial serological examination in routine clinical practice in Japan. The E-plate is a direct enzyme immunoassay test designed to identify the Japanese strain of H. pylori and has been widely applied in large-scale studies in Japanese participants[14,16]. The manufacturer defined the cutoff E-plate titer as 10 U/mL and reported that its accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were 94.0%, 95.2%, 92.6%, 93.8%, and 94.3%, respectively[17].

EGD is another diagnostic tool for H. pylori infection because it is able to not only accurately diagnose gastric malignancies, but also stratify the risk of gastric cancer by evaluating gastritis[3,18]. In Japan, EGD is performed to diagnose H. pylori infection in routine clinical practice. We previously reported that the endoscopic Kyoto classification of gastritis is associated not only with gastric cancer, but also with H. pylori infection[11].

Few studies have described the relationship between the serum anti-H. pylori antibody titers and endoscopic findings. We conducted this cross-sectional study to investigate the association between patients’ baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings, and the serum antibody titer; subsequently, we determined the role of serum antibody titers in these patients.

This retrospective study was approved by the ethical review committee of Hattori Clinic on September 7, 2017. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. All clinical investigations were conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We enrolled consecutive patients who underwent EGD and serum antibody testing at Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic, which is an endoscopy specialty clinic, between September 2016 and August 2017. We included patients who were evaluated for H. pylori infection for the first time. The indications for EGD were the symptoms, abnormal findings on upper gastrointestinal radiography, screening, or surveillance for upper gastrointestinal diseases. The serum antibody titer was measured at the time of EGD. We excluded patients with a history of H. pylori eradication therapy, gastric cancer, or gastrectomy.

We grouped the subjects based on their serum antibody titers. Data on the patients’ baseline characteristics, including age, sex, and indication for EGD, were collected.

The serum antibody titer was measured using the following enzyme-linked immunoassay kit using antigens derived from Japanese individuals: E-plate Eiken H. pylori antibody II kit (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan). The measurable titers were ≥ 3 U/mL and < 100 U/mL. The manufacturer recommended a cut-off value of 10 U/mL for H. pylori positivity. We previously reported that a titer of 3-9.9 U/mL had a lower negative predictive value than a total titer of < 10 U/mL did (83.1% vs 94.3%)[11]. A titer of 3-9.9 U/mL was also reported to indicate the risk of intestinal gastric cancer[15]. The previous study set the cut-off point as 50 U/mL to differentiate the low and high serum antibody titer groups, ensuring that the ratio of patients in both groups was approximately half of all H. pylori-seropositive subjects. A titer of 10-49.9 U/mL was reported to indicate the risk of intestinal gastric cancer, and a titer ≥ 50 U/mL was considered to indicate the risk of diffuse cancer[10].

In the present study, we divided the subjects into four groups according to their serum antibody titer as follows: group A: Titer < 3 U/mL (negative-low), group B: 3-9.9 U/mL (negative-high), Group C: 10-49.9 U/mL (positive-low), and group D: ≥ 50 U/mL (positive-high).

EGD was performed using the Olympus Evis Lucera Elite system with GIF-HQ290 or GIF-H290Z endoscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) by expert physicians who jointly met and discussed the endoscopic images before this study. We performed EGD with the patient under conscious sedation with midazolam and/or pethidine hydrochloride. Other expert physicians retrospectively reviewed the EGD images. Discrepancies in diagnoses between the two sets of physicians were resolved through a discussion between them.

We evaluated the Kyoto classification of gastritis score[19]. The Kyoto classification of gastritis is based on the sum of the scores of the following five endoscopic findings, which are scored on a scale from 0-8: Atrophy, intestinal metaplasia (IM), enlarged folds, nodularity, and redness. A high score represents an increased risk of gastric cancer[15,20]. Gastric atrophy was classified according to the extent of mucosal atrophy, as described by Kimura and Takemoto[21]. Classifications of C-II and C-III were scored as 1, while those of O-I to O-III were scored as 2. IM is typically observed as grayish-white and slightly opalescent patches. IM within the antrum was scored as 1 and IM extending into the corpus was scored as 2. Enlarged folds greater than 5 mm were scored as 1. Nodularity is characterized by the appearance of multiple whitish elevated lesions, mainly in the pyloric gland mucosa. Nodularity was scored as 1. Diffuse redness refers to uniform redness involving the entire fundic gland mucosa. Redness with regular arrangements of collecting venules (RAC) was scored as 1 and that without RAC was scored as 2.

We also investigated gastric and duodenal ulcers. Ulcer scars were considered positive findings. RAC, fundic gland polyps, superficial gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett’s esophagus (BE), and hiatal hernia were considered H. pylori infection-negative endoscopic findings[19]. We defined the three endoscopic findings of hematin (bleeding spots), red streaks (linear erythema), and raised erosion as superficial gastritis. We defined grade A (one or more mucosal breaks of ≤ 5 mm in length) or worse of the Los Angeles classification of GERD as positive. Short-segment BE was classified as BE.

First, we evaluated the association between the serum antibody titer and age, sex, indication, and endoscopic findings using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Cochran-Armitage test, chi-squared test, or polytomous logistic regression analysis for categorical variables in the four groups. Simultaneously, in comparisons between two groups, Steel-Dwass test was used for continuous variables. Second, we compared patients with H. pylori infection (groups C and D) based on age (< 40 years, 40-59 years, and ≥ 60 years) using the Cochran-Armitage test. Subsequently, we conducted a subgroup analysis of H. pylori-infected patients (groups C and D). We evaluated the effect of age, sex, indication, and endoscopic findings on the serum antibody titer in univariate analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test or a binominal logistic regression analysis for categorical variables. We considered age 40-59 years as the reference. Finally, we performed multivariate analysis to identify the factors that were independently associated with the serum antibody titer using a binominal logistic regression analysis of the variables with a P-value less than 0.1 in the univariate analysis. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using Ekuseru-Toukei 2015 software (Social Survey Research Information, Tokyo, Japan).

A total of 919 patients were enrolled. We excluded 37 patients with a history of eradication therapy, four with a history of gastric cancer, and four with a history of gastrectomy. Finally, 874 patients were analyzed. The age of the study participants ranged between 16-95 years (mean: 48.3, standard deviation: 13.8). Thirty-eight percent of the patients were men. The mean Kyoto classification score was 0.43 (standard deviation: 1.09). There were 612 (70%), 141 (16%), 76 (8.7%), and 45 (5.1%) patients in groups A, B, C, and D, respectively (Table 1).

| Group | Total | A | B | C | D | P value |

| Serum antibody titer (U/mL) | < 3 | 3-9.9 | 10-49.9 | ≥ 50 | ||

| Number | 874 | 612 (70.0) | 141 (16.1) | 76 (8.7) | 45 (5.1) | |

| Male | 336 (38.4) | 241 (39.4) | 48 (34.0) | 33 (43.4) | 14 (31.1) | 0.36 |

| Age (yr), continuous, mean ± SD | 48.3 ± 13.8 | 47.8 ± 13.1 | 47.1 ± 14.9 | 52.5 ± 15.8 | 50.9 ± 14.3 | 0.010 |

| Age, categorical | 0.002 | |||||

| < 40 yr | 233 | 167 (71.7) | 43 (18.5) | 15 (6.4) | 8 (3.4) | |

| 40-59 yr | 473 | 342 (72.3) | 70 (14.8) | 33 (7.0) | 28 (5.9) | |

| ≥ 60 yr | 168 | 103 (61.3) | 28 (16.7) | 28 (16.7) | 9 (5.4) | |

| Indication | 0.52 | |||||

| Symptoms | 415 | 295 | 65 | 36 | 19 | |

| Abnormal upper gastrointestinal radiography findings | 93 | 60 | 14 | 12 | 7 | |

| Screening | 227 | 165 | 39 | 14 | 9 | |

| Surveillance for upper gastrointestinal diseases | 139 | 92 | 23 | 14 | 10 | |

| Kyoto classification score, mean ± SD | 0.43 ± 1.09 | 0.11 ± 0.57 | 0.43 ± 0.95 | 1.92 ± 1.70 | 2.33 ± 1.45 | < 0.001 |

| Open-type atrophy | 65 (7.4) | 11 (1.8) | 11 (7.8) | 21 (27.6) | 22 (48.9) | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 46 (5.3) | 8 (1.3) | 7 (5.0) | 19 (25.0) | 12 (26.7) | < 0.001 |

| Enlarged folds | 25 (2.9) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 12 (15.8) | 6 (13.3) | < 0.001 |

| Nodularity | 15 (1.7) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (3.9) | 10 (22.2) | < 0.001 |

| Diffuse redness | 31 (3.5) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (2.1) | 15 (19.7) | 9 (20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Gastric ulcer | 14 (1.6) | 9 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.43 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 19 (2.2) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (1.4) | 10 (13.2) | 4 (8.9) | < 0.001 |

| Regular arrangement of collecting venules | 470 (53.8) | 376 (61.4) | 75 (53.2) | 16 (21.1) | 3 (6.7) | < 0.001 |

| Fundic gland polyps | 311 (35.6) | 259 (42.3) | 48 (34.0) | 4 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Superficial gastritis | 390 (44.6) | 314 (51.3) | 53 (37.6) | 16 (21.1) | 7 (15.6) | < 0.001 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 108 (12.4) | 84 (13.7) | 16 (11.3) | 3 (3.9) | 5 (11.1) | 0.047 |

| Barrett's esophagus | 250 (28.6) | 175(28.6) | 41 (29.1) | 23 (30.3) | 11 (24.4) | 0.95 |

| Hiatal hernia | 105 (12.0) | 75 (12.3) | 17 (12.1) | 10 (13.2) | 3 (6.7) | 0.66 |

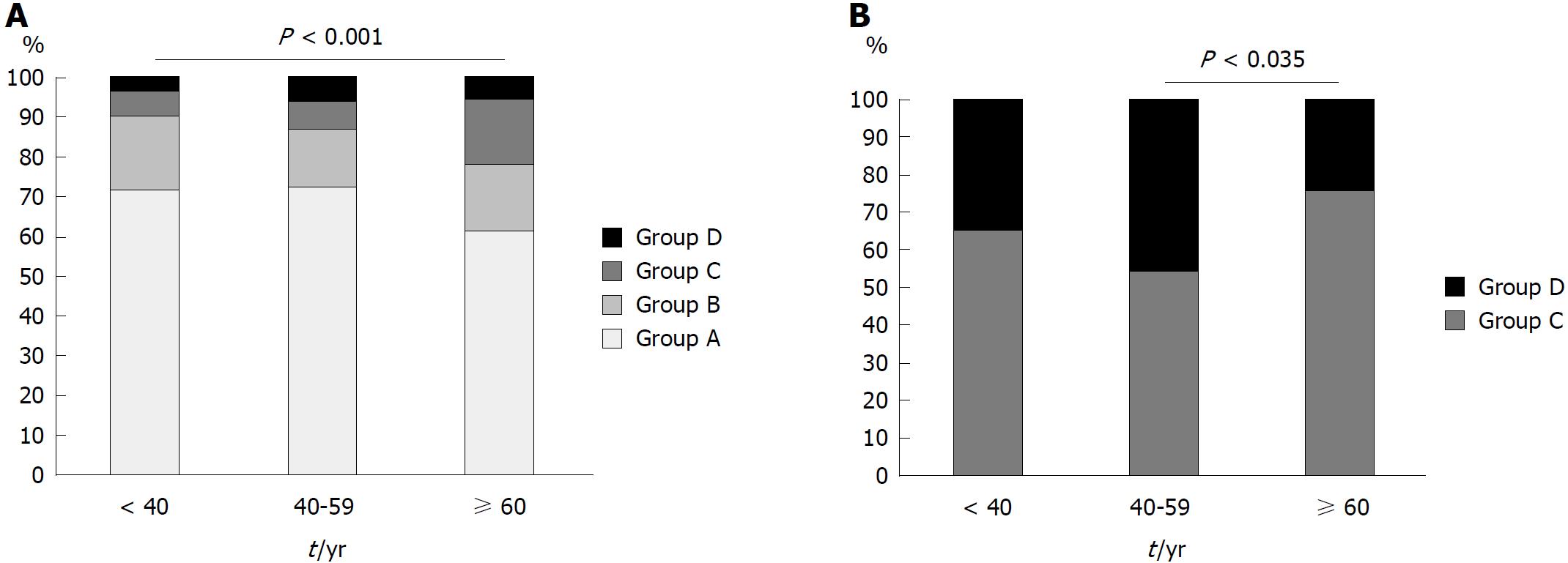

In our analysis of the association between serum antibody titer and baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings in all participants, we found that those in group C were significantly older than those in groups A and B (P = 0.018 and 0.025, respectively, Table 1). There was no difference in sex and indication between the patients in the four groups. We found that the Kyoto classification of gastritis score in group B was higher than that in group A, and those in groups C and D were higher than that in group B (mean score of groups A, B, C, and D: 0.11, 0.43, 1.92, and 2.33, respectively; group A vs B, group B vs C, and group B vs D: P < 0.001; group C vs D: P = 0.32, Table 1). Open-type atrophy (according to the Kimura-Takemoto classification), IM, enlarged folds, nodularity, diffuse redness, and duodenal ulcers occurred more frequently in patients with a higher titer than in those with a lower titer. However, the frequencies of RAC, fundic gland polyps, superficial gastritis, and GERD were lower in patients with a higher titer (Table 1). Representative endoscopic images are shown in Figure 1A-F. The proportion of patients in group C and D who were H. pylori-infected increased with age (< 40 years: 9.9%; 40-59 years: 12.9%; ≥ 60 years: 22.0%; P < 0.001, Figure 2A).

We conducted a sub-analysis of groups C and D to determine the difference between low-positive and high-positive serum antibody titers in H. pylori-infected patients. We compared the proportion of patients in groups C and D, stratified by age, as shown in Figure 2B. The proportion of patients in group D among those aged ≥ 60 years was lower than that in patients aged 40-59 years [odds ratio (OR): 0.38, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.15-0.94, P = 0.035]. There was no difference between patients aged < 40 and those between 40-59 years in terms of the proportion of patients in group D (OR: 0.63, 95%CI: 0.23-1.7, P = 0.36). In our comparison of the endoscopic findings of patients in groups C and D, we found that the frequencies of nodularity (P = 0.0042) and open-type atrophy (P = 0.018) were higher in group D than those in group C. The frequency of RAC was lower in group D than that in group C (P = 0.040). We evaluated the effect of patients’ baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings on the serum antibody titer using multivariate analysis. Age ≥ 60 years (OR: 0.24, 95%CI: 0.083-0.70, P = 0.0090), nodularity (OR: 7.1, 95%CI: 1.6-31, P = 0.0094), and open-type atrophy (OR: 3.9, 95%CI: 1.4-10, P = 0.0076) were independently associated with the serum antibody titer in H. pylori-infected patients (Table 2).

We compared the endoscopic findings of H. pylori-infected patients aged < 60 years and those ≥ 60 years, as shown in Table 3. Intestinal metaplasia and gastric atrophy were related to age ≥ 60 years in group C and D.

| Group C | P value | Group D | P value | |||

| Age < 60 yr | Age ≥ 60 yr | Age < 60 yr | Age ≥ 60 yr | |||

| Number | 48 | 28 | 36 | 9 | ||

| Kyoto classification score, mean ± SD | 1.52 ± 1.56 | 2.61 ± 1.75 | 0.0068 | 2.19 ± 1.53 | 2.89 ± 0.928 | 0.084 |

| Open-type atrophy | 7 | 14 | 0.0014 | 14 | 8 | 0.0098 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 4 | 15 | < 0.001 | 6 | 6 | 0.0062 |

| Enlarged folds | 8 | 4 | 1.0 | 3 | 3 | 0.084 |

| Nodularity | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 10 | 0 | 0.17 |

| Diffuse redness | 9 | 6 | 0.77 | 9 | 0 | 0.17 |

| Gastric ulcer | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 4 | 6 | 0.16 | 4 | 0 | 0.57 |

| Regular arrangement of collecting venules | 12 | 4 | 0.38 | 3 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Fundic gland polyps | 4 | 0 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Superficial gastritis | 11 | 5 | 0.77 | 7 | 0 | 0.31 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 2 | 0.26 |

| Barrett's esophagus | 13 | 10 | 0.45 | 9 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Hiatal hernia | 5 | 5 | 0.48 | 3 | 0 | 1.0 |

In this study, we investigated the association between patients’ baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings and the serum antibody titer, and we clarified the role of serum antibody titers in patients with H. pylori infection. We found that nodularity and endoscopic open-type atrophy correlated with a high serum antibody titer in H. pylori-infected patients. In patients aged > 60 years, the serum antibody titer tended to decrease and IM tended to be more prevalent. Higher bacterial counts induce intense immune responses, resulting in higher serum antibody titers, while genetic differences among human hosts may affect the antibody levels in response to pathogens[4,22]. Tatemichi et al[14,23] demonstrated that a low-positive serum antibody titer was associated with intestinal-type gastric cancer and a high-positive titer was considered to indicate a high risk of diffuse-type cancer. The intestinal type of cancer develops through a sequence in which atrophy progresses and IM appears as a person ages, while the diffuse type of cancer is associated with high mucosal inflammation, particularly in young patients and those with nodularity[2,4,6,24-26]. In this study, we elucidated that the natural history of H. pylori infection is as follows: 40-59-year-old H. pylori-infected patients develop high inflammatory gastritis, frequently with nodularity and a high serum antibody titer, and they have a higher risk of developing diffuse-type gastric cancer. Subsequently, some H. pylori-infected patients older than 60 years of age have less gastric mucosal inflammation, progression of gastric atrophy, IM, decreased serum antibody titers, and the risk of developing intestinal-type gastric cancer.

In our investigation of all subjects, endoscopic findings indicating H. pylori infection were associated not only with positive or negative serum antibodies, but also with the serum antibody value. Regardless of whether they have an H. pylori infection, patients with a high serum antibody titer are more likely to have H. pylori infection-related endoscopic findings and are less likely to have H. pylori infection-negative endoscopic findings than are those with a lower serum antibody titer. Endoscopic findings are related to the risk of gastric cancer; therefore, these results confirmed that the serum antibody titer is associated with the risk of gastric cancer[2,6].

The H. pylori infection rate is declining in Japan; however, our study indicated that a large number of people have negative antibodies, but high titers. Since some previous studies have demonstrated that patients with negative-high serum antibody titers, especially those with H. pylori infection, were at a risk of developing intestinal gastric cancer, these results should be considered in clinical practice[10,11,14,15].

We previously reported that the H. pylori infection rate was 17% in group B[11]. The infection rate at the time serum antibodies were measured was 13% in people < 40 years old, 15% for those aged 40-59 years, and 25% for those ≥ 60 years. Ueda et al[27] described that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Japan was the highest in patients born between 1940-1949 and then decreased in those born in the ensuing years. Our results were concordant with those of their reports and might indicate the current infection rate in urban areas in Japan.

This study has some limitations. The subjects included in the study were limited to outpatients. In the future, population-based research is expected. We did not diagnose H. pylori infection accurately because this study based on serum antibodies for diagnostic method. Investigating H. pylori infection with UBT is needed to determine the fluctuations in serum antibody titers in a time series in H. pylori-infected patients. Cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), which is a virulent form of H. pylori, was also not evaluated because 95% of Japanese patients with H. pylori infection have East Asian-type CagA[28]. Further investigations in those who do not have East Asian-type CagA-positive H. pylori infection is necessary.

In H. pylori-infected patients, high titers of serum anti-H. pylori antibodies were associated with gastric nodularity and atrophy, and the serum antibody titer tended to decrease in 60-year-old patients. Serum antibody titer reflects gastric mucosal inflammation; therefore, patient with high antibody titer may be at risk for diffuse gastric cancer and should be carefully screened in clinical practice.

Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody titer and endoscopic findings are associated with the risk of gastric cancer.

Few studies have reported on the relationship between the serum antibody titer and endoscopic findings.

To clarify the role of serum anti-H. pylori antibody titers in gastric cancer.

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the effect of patients’ baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings on their serum antibody titers. We excluded patients with a history of eradication therapy.

Gastric nodularity, atrophy, and age 40-59 years (vs age ≥ 60 years) were correlated with a high serum antibody titer in H. pylori-infected patients.

Serum antibody titer reflects gastric mucosal inflammation

In the future, population-based research is expected.

We would like to thank Kanazawa T, Matsumoto S, Yoshida S, Isomura Y, Arano T, Kinoshita H, Kataoka Y, Ohki D, Fukagawa K, and Sekiba K for performing esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

| 1. | Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 2089] [Article Influence: 232.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Toyoshima O, Yamaji Y, Yoshida S, Matsumoto S, Yamashita H, Kanazawa T, Hata K. Endoscopic gastric atrophy is strongly associated with gastric cancer development after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2140-2148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toyoshima O, Tanikawa C, Yamamoto R, Watanabe H, Yamashita H, Sakitani K, Yoshida S, Kubo M, Matsuo K, Ito H. Decrease in PSCA expression caused by Helicobacter pylori infection may promote progression to severe gastritis. Oncotarget. 2017;9:3936-3945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sakitani K, Nishizawa T, Arita M, Yoshida S, Kataoka Y, Ohki D, Yamashita H, Isomura Y, Toyoshima A, Watanabe H. Early detection of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication due to endoscopic surveillance. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O’Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012;44:74-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tonkic A, Tonkic M, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2012;17 Suppl 1:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Burucoa C, Delchier JC, Courillon-Mallet A, de Korwin JD, Mégraud F, Zerbib F, Raymond J, Fauchère JL. Comparative evaluation of 29 commercial Helicobacter pylori serological kits. Helicobacter. 2013;18:169-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Ueda J, Okuda M, Nishiyama T, Lin Y, Fukuda Y, Kikuchi S. Diagnostic accuracy of the E-plate serum antibody test kit in detecting Helicobacter pylori infection among Japanese children. J Epidemiol. 2014;24:47-51. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kishikawa H, Kimura K, Takarabe S, Kaida S, Nishida J. Helicobacter pylori Antibody Titer and Gastric Cancer Screening. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:156719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Arita M, Kataoka Y, Sakitani K, Yoshida S, Yamashita H, Hata K, Watanabe H, Suzuki H. Helicobacter pylori infection in subjects negative for high titer serum antibody. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1419-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Marchildon P, Balaban DH, Sue M, Charles C, Doobay R, Passaretti N, Peacock J, Marshall BJ, Peura DA. Usefulness of serological IgG antibody determinations for confirming eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2105-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, Okamoto M, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Shiratori Y, Saito K, Yokouchi K, Omata M. Weak response of Helicobacter pylori antibody is high risk for gastric cancer: a cross-sectional study of 10,234 endoscoped Japanese. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:148-153. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Tatemichi M, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsugane S; JPHC Study Group. Clinical significance of IgG antibody titer against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2009;14:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kiso M, Yoshihara M, Ito M, Inoue K, Kato K, Nakajima S, Mabe K, Kobayashi M, Uemura N, Yada T. Characteristics of gastric cancer in negative test of serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen test: a multicenter study. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:764-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matsuo T, Ito M, Takata S, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer among Japanese. Helicobacter. 2011;16:415-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chemical E. E-plate Eiken H. pylori antibody II. 2011. Accessed May 26. 2018; Available from: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ivd/PDF/170005_22200AMX00935000_A_01_02.pdf. |

| 18. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3248] [Article Influence: 129.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Kato M. Endoscopic Findings of H. pylori Infection. Helicobacter pylori. Tokyo: Springer Japan 2016; 157-167. |

| 20. | Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Niikura R, Hayakawa Y, Yamada A, Koike K. Association between gastric cancer and the Kyoto classification of gastritis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1581-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87-97. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 22. | Rubicz R, Leach CT, Kraig E, Dhurandhar NV, Duggirala R, Blangero J, Yolken R, Göring HH. Genetic factors influence serological measures of common infections. Hum Hered. 2011;72:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tatemichi M, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsugane S; Japan Public Health Center Study Group. Different etiological role of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection in carcinogenesis between differentiated and undifferentiated gastric cancers: a nested case-control study using IgG titer against Hp surface antigen. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:360-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kamada T, Sugiu K, Hata J, Kusunoki H, Hamada H, Kido S, Nagashima Y, Kawamura Y, Tanaka S, Chayama K. Evaluation of endoscopic and histological findings in Helicobacter pylori-positive Japanese young adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:258-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yoshida T, Kato J, Inoue I, Yoshimura N, Deguchi H, Mukoubayashi C, Oka M, Watanabe M, Enomoto S, Niwa T. Cancer development based on chronic active gastritis and resulting gastric atrophy as assessed by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody titer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1445-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ueda J, Gosho M, Inui Y, Matsuda T, Sakakibara M, Mabe K, Nakajima S, Shimoyama T, Yasuda M, Kawai T. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by birth year and geographic area in Japan. Helicobacter. 2014;19:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:629-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chiba T, Kishikawa H, Romano M S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y