Published online Apr 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i15.1632

Peer-review started: February 11, 2018

First decision: March 9, 2018

Revised: March 16, 2018

Accepted: March 31, 2018

Article in press: March 30, 2018

Published online: April 21, 2018

Processing time: 68 Days and 19.7 Hours

To determine short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) using the stag beetle (SB) knife, a scissor-shaped device.

Seventy consecutive patients with 96 early esophageal neoplasms, who underwent ESD using a SB knife at Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center, Japan, between April 2010 and August 2016, were retrospectively evaluated. Clinicopathological characteristics of lesions and procedural adverse events were assessed. Therapeutic success was evaluated on the basis of en bloc, histologically complete, and curative or non-curative resection rates. Overall and tumor-specific survival, local or distant recurrence, and 3- and 5-year cumulative overall metachronous cancer rates were also assessed.

Eligible patients had dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia (22%) or early cancers (squamous cell carcinoma, 78%). The median procedural time was 60 min and on average, the lesions measured 24 mm in diameter, yielding 33-mm tissue defects. The en bloc resection rate was 100%, with 95% and 81% of dissections deemed histologically complete and curative, respectively. All procedures were completed without accidental incisions/perforations or delayed bleeding. During follow-up (mean, 35 ± 23 mo), no local recurrences or metastases were observed. The 3- and 5-year survival rates were 83% and 70%, respectively, with corresponding rates of 85% and 75% for curative resections and 74% and 49% for non-curative resections. The 3- and 5-year cumulative rates of metachronous cancer in the patients with curative resections were 14% and 26%, respectively.

ESD procedures using the SB knife are feasible, safe, and effective for treating early esophageal neoplasms, yielding favorable short- and long-term outcomes.

Core tip: Various devices designed for endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are currently under investigation for their usefulness in the treatment of early esophageal neoplasms. This study aimed to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of ESD using the stag beetle (SB) knife, a scissor-shaped device. Seventy-four patients with 101 esophageal lesions underwent resection via SB-knife ESD. Rates of en bloc, histologically complete, and curative resections were 100%, 95%, and 81%, respectively. The 3- and 5-year survival rates were 83% and 70%, respectively. The SB knife allows safe and effective ESD of early esophageal neoplasms.

- Citation: Kuwai T, Yamaguchi T, Imagawa H, Miura R, Sumida Y, Takasago T, Miyasako Y, Nishimura T, Iio S, Yamaguchi A, Kouno H, Kohno H, Ishaq S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal neoplasms using the stag beetle knife. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(15): 1632-1640

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i15/1632.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i15.1632

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cancer worldwide and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally[1,2]. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the commonest histotype of esophageal cancer in Japan and worldwide[1,3]. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, outcomes in these patients remain poor, with five-year survival rates of 15%-20%[4,5]. Aggressive use of enhanced imaging for screening and advanced magnification endoscopy systems have aided in early diagnosis. However, given the many possible comorbidities in patients undergoing conventional treatments (such as esophagectomy) and the greater likelihood of incomplete resection through endoscopic mucosal resection, researchers are now actively investigating endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of superficial esophageal neoplasms[6-8].

A number of conventional ESD devices (i.e., dual, flush, insulated-tip, and hook knives) have been utilized for esophageal ESD[9-14]. Compared to those of the stomach, the thin wall (with no serosa) and narrow lumen of the esophagus make ESD inherently more challenging. The endoscopic maneuverability difficulties imposed by conventional ESD devices are also problematic, particularly the lack of fixation to targets and the fact that these devices are partially or entirely uninsulated. Constraints of this sort are conducive to unintentional incisions, increasing the potential risk of adverse events such as perforation and mediastinal emphysema[15-18].

On the other hand, the stag beetle (SB) knife (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd., Akita, Japan), with its ability to grasp, assess, and then cut targeted tissue, allows endoscopists to maintain adequate dissection planes, preventing inadvertent injury to the muscular layer and promoting safe ESD[19-23]. Although early experiences at selected institutions suggest that the SB knife is safe and effective, no large series of patients or long-term outcomes have been reported to date[21-24]. The aim of this study was to investigate use of the SB knife for ESD of early esophageal neoplasms, assessing both feasibility and safety. Subsequent short- and long-term clinical outcomes were examined as well.

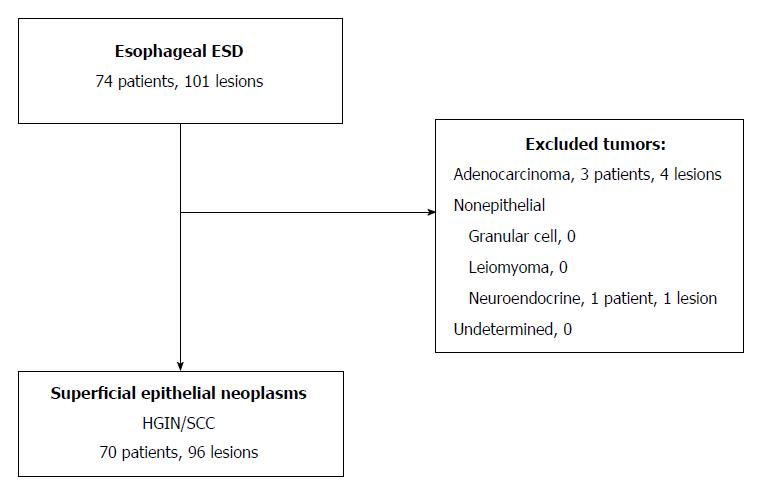

A single-center retrospective review of collected data was conducted, examining 74 consecutive patients with 101 esophageal lesions who underwent resection via SB-knife ESD between April 2010 and August 2016 at Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center, Japan (Figure 1). All patients underwent resection using only SB-knife ESD during this time period. Approved by the National Hospital Organization Kure Medical Center and the Chugoku Cancer Center Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee on 3 October 2016, the study incorporated good clinical practice, conforming to Declaration of Helsinki principles. All lesions were diagnosed preoperatively during chromoendoscopy, identifying areas for biopsy through narrow-band imaging or iodine staining. Inclusion criteria were patients with superficial esophageal neoplasms (SENs), consisting of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or SCC. Exclusion criteria included patients with adenocarcinoma, non-epithelial tumors (i.e., granular cell tumors, leiomyomas, and neuroendocrine tumors) or undetermined tumors.

All patients were informed of the risks and benefits of ESD and provided written informed consent. ESD was contraindicated in patients with serious comorbidities, distant metastasis, or massive submucosal invasion.

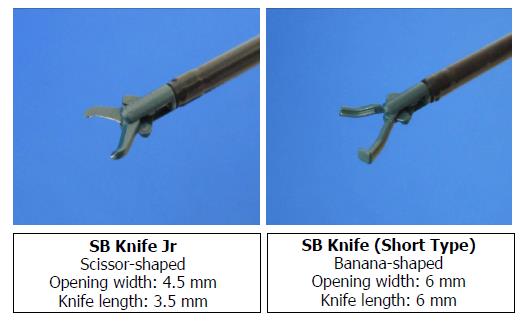

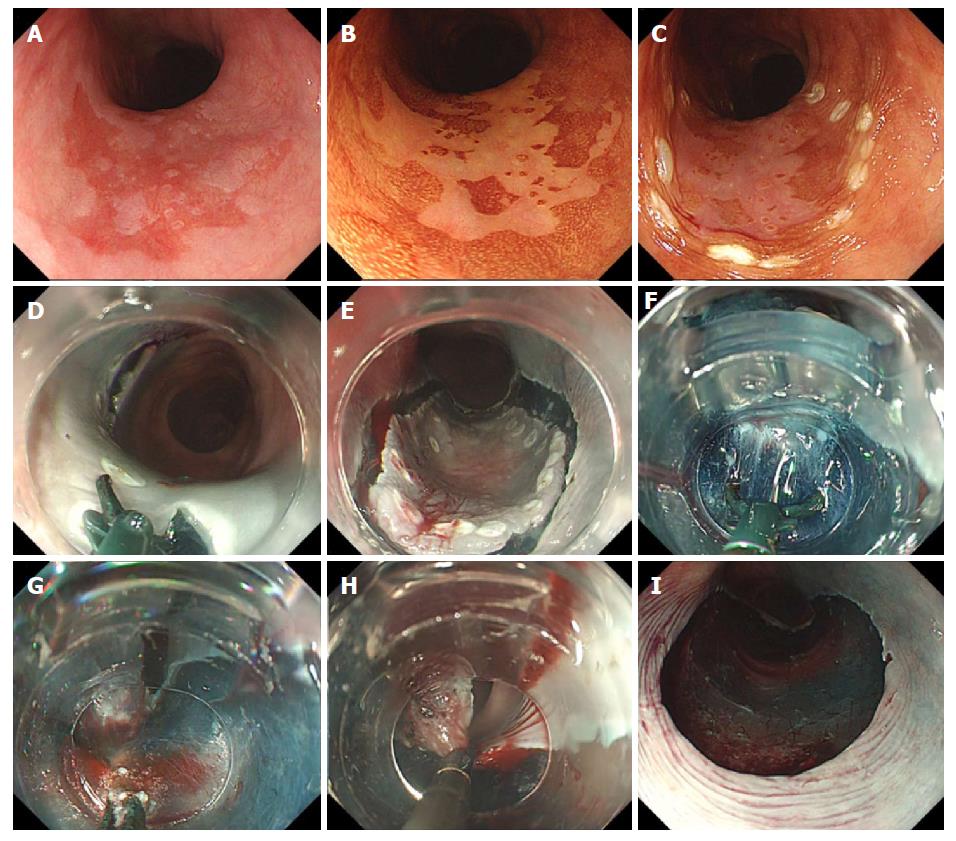

ESD procedures were performed by four board-certified endoscopists of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, three with no previous conventional esophageal ESD experience and one with low experience (10 cases). Patients received intravenous nitrazepam for sedation, and cardiorespiratory function was monitored throughout the procedure. A single-channel endoscope equipped with a water jet (GIF-H260Z; Olympus Corp, Tokyo, Japan) and attached transparent tip hood was routinely used, along with carbon dioxide insufflation. Initially, the outside margin of each lesion was marked using argon plasma coagulation in forced coagulation mode; the esophageal mucosa was injected with 0.4% sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp; Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) mixed with a small amount of indigo carmine. Circumferential excision was then carried out with the SB Knife Jr (4.5-mm opening width, 3.5-mm length; Sumitomo Bakelite Co.) (Figure 2). For submucosal dissection, the SB Knife Short (6-mm opening width, 6-mm length) (Figure 2) was often preferred, because detachment/peeling of the submucosa was faster, and it was less likely to engage the muscular layer, given the curved shape of the blade. The SB knife allowed grasping of the targeted segment, which was then cut using a high-frequency generator (VIO300D; ERBE, Tubingen, Germany) in the endo-cut Q mode (effect 1) for incising mucosa and dissecting submucosa. The soft coagulation mode (effect 5.40 W) was used for hemostasis. If repeated coagulation was required, hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus Corp.) were applied to facilitate endoscopic hemostasis. The procedure was continued until resection was completed (Figure 3).

In instances of semi-circumferential or circumferential ESD, intralesional diluted triamcinolone acetonide injected on postoperative day 2 [Kenacort (40-80 mg); Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., New York, NY, United States] or oral prednisolone (30 mg/d) was prescribed and tapered gradually over several weeks[25] to prevent postoperative stricture[26,27].

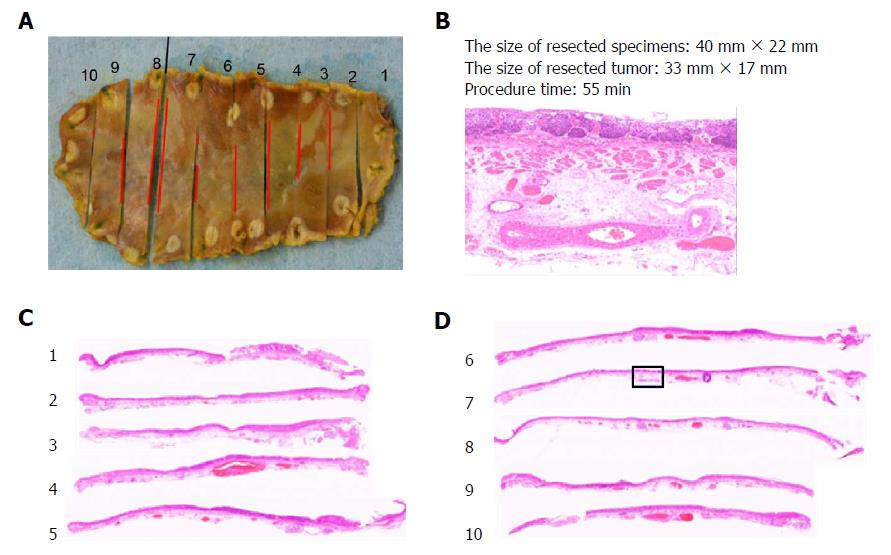

Resected specimens were immediately fixed in 10% buffered formalin, with samples later selected for routine processing, embedding in paraffin, and slide preparation (3-4 μm, hematoxylin & eosin stain). The histotype, depth of invasion, and resection margins (vertical and lateral) of the lesions were assessed microscopically (Figure 4) using an optical micrometer to measure invasive areas. The tumor size, anatomic location (upper one-third, middle one-third, or lower one-third of the esophagus), and extent (%) of esophageal circumferential involvement were documented. Rates of en bloc resection, histologically complete resection (i.e., en bloc resection with negative lateral and vertical margins), and curative or non-curative resection served as indices of therapeutic success. Curative resection was defined as complete tumor resection with invasion ≤ 200 μm below the deep border of the lamina muscularis mucosae and no lymphovascular involvement[8].

Immediate adverse events such as perforation, delayed bleeding, and postoperative pneumonia and delayed adverse events such as esophageal stricture were recorded.

To monitor patients, esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed 3-6 mo and 1 year following ESD and annually thereafter; computed tomography was also performed annually. Three- and 5-year overall survival rates were assessed for the entire study cohort. SENs detected > 1 year after curative resection by ESD were considered metachronous cancers. Cumulative overall metachronous cancer rates during the 3- and 5-year periods were also assessed.

Continuous variables were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation or median and range, as appropriate, and categorical variables as frequency or number of occurrences. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to analyze survival and metachronous cancer rates. A log-rank test was used to evaluate the significance of differences between curves, and a P value of less than 5% was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

A total of 96 SENs in 70 patients qualified for analysis. One subject was excluded, having received a final diagnosis of nonepithelial tumor, and 4 subjects were excluded, having received a final diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Figure 1). Fifteen patients had multiple lesions, harboring two (n = 9), three (n = 3), four (n = 1), or five (n = 2) lesions. Mean age of the study population (n = 70; 84% men) was 67 ± 10 years (Table 1). By location, 11% of lesions involved the upper one-third of the esophagus, 55% the middle one-third, and 34% the lower one-third. Macroscopically, majority of the lesions were depressed (90%) rather than elevated (7%) or flat (2%).

| Characteristics | Value |

| Number of patients | 70 |

| Number of lesions | 96 |

| Age, mean ± SD (range), yr | 67 ± 10 (43-87) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 59 (84) |

| Female | 11 (16) |

| Location of the tumor in the esophagus | |

| Upper one-third | 11 (11) |

| Middle one-third | 53 (55) |

| Lower one-third | 33 (34) |

| Gross appearance | |

| Depressed | 86 (90) |

| Elevated | 7 (7) |

| Flat | 2 (2) |

| Mixed | 1 (1) |

| Resected specimen size, mean ± SD (range), mm | 33 ± 14 (9-75) |

| Resected tumor size, mean ± SD (range), mm | 24 ± 13 (1-64) |

| Luminal extent | |

| < 1/2 | 59 (61) |

| ≥ 1/2, < 2/3 | 20 (21) |

| ≥ 2/3 | 17 (18) |

| Histopathologic features | |

| Dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia | 21 (22) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 75 (78) |

| Epithelial lining | 15 (20) |

| Lamina propria mucosae | 31 (41) |

| Muscularis mucosae | 13 (17) |

| Submucosa (SM1) | 2 (3) |

| Submucosa (SM2 or deeper) | 14 (19) |

Resected specimens measured 33 ± 14 mm on average, with a mean tumor size of 24 ± 13 mm. Most tumors (61%) involved < one-half of the esophageal luminal circumference. Histopathological diagnoses were as follows: dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia (22%), or SCC (78%). Typically, invasive SCCs were limited to the lamina propria mucosae (41%), with SM2 or deeper infiltration accounting for 19% (Table 1).

Short-term outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The median procedural time was 60 min (range, 25-305 min). Rates of en bloc resection, histologically complete resection, and curative resection were 100%, 95%, and 81%, respectively.

| 95%CI | |

| Procedure duration, median (range) | 60 (25-305) |

| En bloc resection | 96 (100) [96.2-100] |

| Complete resection with negative margins | 91 (95) [88.4-97.8] |

| Curative resection | 78 (81) [72.3-87.8] |

| Adverse events | |

| Perforation | 0 (0) [0-3.9] |

| Delayed bleeding | 0 (0) [0-3.9] |

| Pneumonia | 3 (3) [1.1-8.8] |

| Esophageal stricture | 7 (7) [3.6-14.3] |

All lesions were safely resected without any unintentional incisions/perforations or delayed bleeding episodes. Pneumonia was observed in 3% of patients and managed through antibiotic treatment. To prevent postoperative stricture after semi-circumferential ESD, intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (3 patients) or oral prednisolone (7 patients) was administered. Esophageal strictures were encountered in seven patients, one requiring balloon dilatation (Table 2).

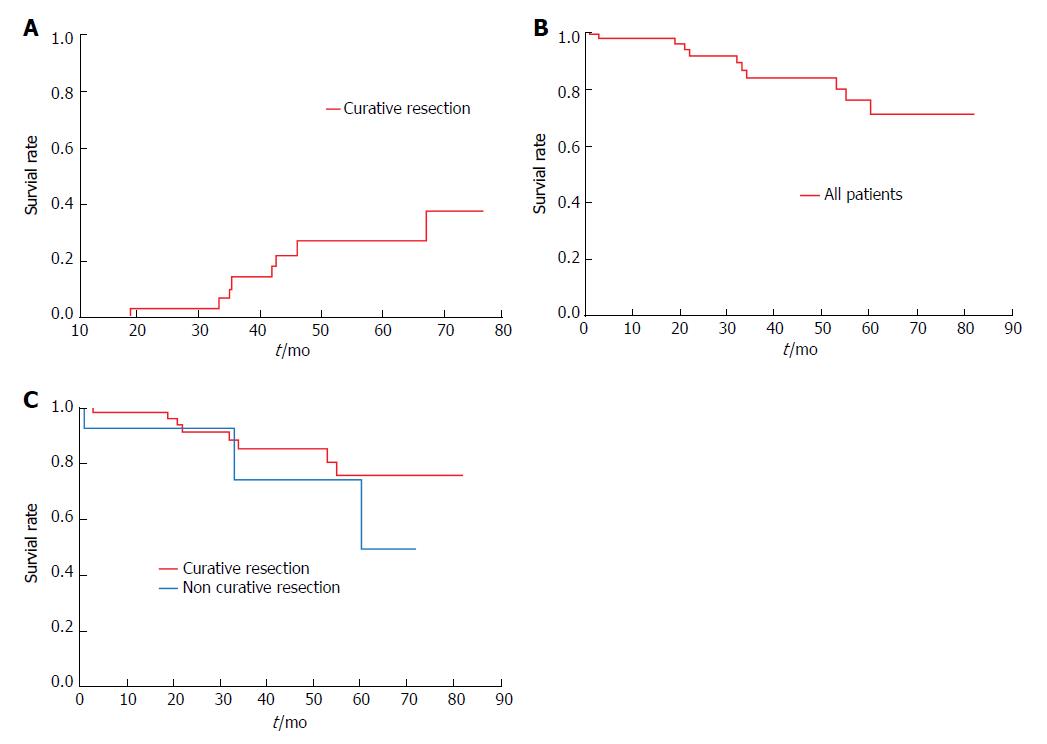

Curative resection was achieved in 57 patients, three of whom received additional chemoradiotherapy (CRT). One of these three patients later developed metachronous cancer. Seven of the 54 patients who were given no additional treatment also developed metachronous cancers. The 3- and 5-year cumulative rates of metachronous cancer in patients with curative resections were 14% and 26%, respectively (Figure 5A). Non-curative resection was achieved in 13 patients, seven of whom underwent additional treatment, either surgery (n = 4), chemotherapy (n = 1), or CRT (n = 2). No instances of local recurrence or metastasis were observed in any patient during the mean follow-up period of 35 ± 23 mo.

Three- and 5-year overall survival rates for the study cohort were 83% and 70%, respectively (Figure 5B), with corresponding rates of 85% and 75% in curative resections, and 74% and 49% in non-curative resections (Figure 5C). However, the difference in survival between curative and non-curative resections by ESD was not statistically significant. Eleven of 70 patients (curative resections, 8/57; non-curative resections, 3/13) died during follow-up. In patients with curative resections, causes of death included isolated instances of unknown primary cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, lung cancer, pharyngeal carcinoma, drowning, and aspiration pneumonia, as well as two instances of interstitial pneumonia. Causes of death after non-curative resection were oropharyngeal carcinoma, liver cirrhosis, and aspiration pneumonia, each a single occurrence. None of the deaths was directly attributable to esophageal neoplasms.

Our study suggests that the SB knife is safe and effective when used for ESD of early esophageal neoplasms. This technique resulted in high rates of en bloc resection (100%), histologically complete resection (95%), and curative resection (81%), with a low incidence of procedural adverse events, despite three of the certified endoscopists having either limited or no experience of esophageal ESD. Specifically, there were no unintentional incisions/perforations or delayed bleeding events. Furthermore, no patient experienced local recurrences or metastases in the long term, and the overall survival rates were highly favorable and similar to those for other devices[8,28,29].

Data reported here are consistent with those of a previous study demonstrating the safety and efficacy of the SB knife as a means of esophageal ESD in 15 patients[23]. Importantly, overall adverse events for the SB knife are relatively low[10-14]. Its unique scissor-action allows surgeons to grasp and pull the targeted tissue away from the muscularis and then inspect the area before cutting for more controlled resection and avoidance of perforation. Unlike other devices[30,31], no complex adjustments or special endoscopic techniques are required. This facilitated the acquisition of implementation skills by even general endoscopists[19,30] and shortened the training process[31-34], and we obtained good results from the first case itself. The notable absence of perforation reflects the safe and easy use of the SB knife in this setting, despite cyclic respiratory and cardiac fluctuations encountered during esophageal ESD. This tool also acts as a hemostatic clamp, eliminating the need for separate hemostatic forceps, making the procedure simple and cost-effective, and encouraging high resectability rates.

We would like to emphasize that no tumors recurred when the SB knife was used for esophageal ESD. Earlier studies have already reported positive short-term treatment outcomes (i.e., resection rates) using the SB knife in small series[23,24]. The present results indicate for the first time, in the largest series reported to date, that use of the SB knife offers excellent short- and long-term outcomes in treating early esophageal neoplasms. The high resection rates achieved and absence of local recurrence or metastasis during 35 ± 23 mo of follow-up constitute a new paradigm shift in the treatment of SEN[14,16,17,28,35]. Consistent with other published studies[36], several of our patients with curative resections (8/57) developed metachronous lesions, including one of three who received additional CRT. This finding underscores the need for follow-up monitoring on a regular basis.

On analyzing longer-term patient outcomes, 3- and 5-year survival rates tended to be slightly, but not significantly, poorer if resections were non-curative (74% and 49%, respectively) rather than curative (85% and 75%, respectively). Although non-curatively resected esophageal cancer is typically associated with a poor prognosis, none of the deaths recorded in the present study were a direct result of esophageal cancer. The aforementioned trend may then have a singular explanation. As ESD ordinarily is not indicated in patients with SM-level invasive cancer, such patients who agreed to undergo ESD for excisional biopsy (the goal being localized control) were included in the non-curative resection group. Consequently, it appears that achieving local control of esophageal cancer via ESD is quite feasible in elderly patients and in those with serious underlying diseases, who ultimately may die from other causes. By seemingly benefitting from the safe performance of esophageal ESD, we have thereby demonstrated the efficacy of the SB knife in a high-risk population.

Contrary to earlier concerns that the use of the SB knife might prolong ESD procedures[16,18], we found that it greatly expedited ESD. The median time needed to complete ESD was 60 min (mean, 78 min), approximating the time required for conventionally performed ESD (median, 90 min) in one large multicenter study[8].

Our study has three limitations. It is retrospective, although data were collected from consecutive patients, it was conducted at a single center; and no comparison with another device was attempted. However, strengths of the study include the sizeable patient population and the extended follow-up period, both providing valuable data on the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of SB knife usage for esophageal ESD.

In conclusion, ESD procedures using the SB knife are feasible, safe, and effective for treating early esophageal neoplasms, yielding favorable short- and long-term outcomes. No perforation occurred in our study population, attesting to the innovative design of the SB knife, which allows better control for safer dissection. The availability of this tool may promote widespread adoption of ESD to treat early-stage cancers of the esophagus. There is need to conduct RCT studies to compare this new innovative device with established devices.

Several conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) devices have been utilized for esophageal ESD. The thin wall with no serosa and narrow lumen of the esophageal wall make ESD more challenging in the esophagus. The restricted endoscopic maneuvering required with conventional ESD devices is also problematic owing to lack of fixation to targets and the fact that these devices are partially or entirely uninsulated. These factors can lead to unintentional incisions, increasing the potential risk of adverse events such as perforation and mediastinal emphysema.

The stag beetle (SB) knife, with its ability to grasp, assess, and then cut the targeted tissue allows endoscopists to maintain adequate dissection planes, preventing inadvertent injury to the muscular layer for safe ESD. Because of these advantages, the SB Knife is gaining acceptance, but relevant long-term outcome data is limited.

The aim of this study was to investigate use of the SB knife for ESD of early esophageal neoplasms, assessing both feasibility and safety. The subsequent short- and long-term clinical outcomes were examined as well.

We retrospectively reviewed 70 consecutive patients with 96 early esophageal neoplasms (HGIN/SCC) treated using ESD. An SB knife was used routinely in all procedures. Clinicopathologic characteristics of the lesions and rates of procedural adverse events, en bloc and histologically complete resection, overall and tumor-specific survival, and local or distant recurrence were assessed.

The en bloc resection rate was 100%, with 95% and 81% of dissections deemed histologically complete and curative, respectively. All procedures were completed without accidental incisions/perforations or delayed bleeding. During follow-up (mean, 35 ± 23 mo), no local recurrences or metastases were observed. The 3- and 5-year survival rates were 83% and 70%, respectively. The 3- and 5-year cumulative rates of metachronous cancer in the patients with curative resections were 14% and 26%, respectively.

ESD procedures using the SB knife are feasible, safe, and effective for treating early esophageal neoplasms, yielding favorable short- and long-term outcomes. No perforation occurred in our study population, attesting to the innovative design of the SB knife, which allows better control for safer dissection.

The availability of this tool may promote widespread adoption of ESD to treat early-stage cancers of the esophagus. There is a need to conduct RCT studies to compare this new innovative device with established devices.

Writing support was provided by Cactus Communications. The authors extend thanks to Naoko Matsumoto for data collection and administrative assistance.

| 1. | Giri S, Pathak R, Aryal MR, Karmacharya P, Bhatt VR, Martin MG. Incidence trend of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: an analysis of Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yamamoto M, Weber JM, Karl RC, Meredith KL. Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer: review of the literature and institutional experience. Cancer Control. 2013;20:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Napier KJ, Scheerer M, Misra S. Esophageal cancer: A Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, staging workup and treatment modalities. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:112-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 4. | Kosugi S, Sasamoto R, Kanda T, Matsuki A, Hatakeyama K. Retrospective review of surgery and definitive chemoradiotherapy in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus aged 75 years or older. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:360-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Allen JW, Richardson JD, Edwards MJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a review and update. Surg Oncol. 1997;6:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Takahashi H, Arimura Y, Masao H, Okahara S, Tanuma T, Kodaira J, Kagaya H, Shimizu Y, Hokari K, Tsukagoshi H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection is superior to conventional endoscopic resection as a curative treatment for early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:255-264, 264.e1-264.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 7. | Martelli MG, Duckworth LV, Draganov PV. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Is Superior to Endoscopic Mucosal Resection for Histologic Evaluation of Barrett’s Esophagus and Barrett’s-Related Neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:902-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tsujii Y, Nishida T, Nishiyama O, Yamamoto K, Kawai N, Yamaguchi S, Yamada T, Yoshio T, Kitamura S, Nakamura T. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:775-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Fukami N, Ryu CB, Said S, Weber Z, Chen YK. Prospective, randomized study of conventional versus HybridKnife endoscopic submucosal dissection methods for the esophagus: an animal study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1246-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hirasawa D, Oyama T. [Hook knife method of ESD for early esophageal cancer]. Nihon Rinsho. 2011;69 Suppl 6:248-254. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Motohashi O, Nishimura K, Nakayama N, Takagi S, Yanagida N. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (two-point fixed ESD) for early esophageal cancer. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:176-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, Morita S, Kominato K, Tanaka M, Miyata Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S67-S70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Goto O, Ono S, Niimi K, Yamamichi N, Oka M, Ichinose M, Omata M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Azuma M, Katada C, Sasaki T, Ishido K, Naruke A, Katada N, Koizumi W. A phase II study of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms (KDOG 0901). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:704-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhong H, Ma L, Zhang Y, Shuang J, Qian Y, Sheng Y, Wang X, Miao L, Fan Z. Nonsurgical treatment of 8 cases with esophageal perforations caused by ESD. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:21760-21764. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Oyama T. Esophageal ESD: technique and prevention of complications. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:201-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Toyonaga T, Man-i M, East JE, Nishino E, Ono W, Hirooka T, Ueda C, Iwata Y, Sugiyama T, Dozaiku T. 1,635 Endoscopic submucosal dissection cases in the esophagus, stomach, and colorectum: complication rates and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1000-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cao Y, Liao C, Tan A, Gao Y, Mo Z, Gao F. Meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2009;41:751-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Takata S, Kanao H, Chayama K. Usefulness and safety of SB knife Jr in endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2012;24 Suppl 1:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kuwai T, Yamaguchi T Imagawa H, Sumida Y, Takasago T, Miyasako Y, Nishimura T, Iio S, Yamaguchi A, Kouno H, Kohno H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early colorectal neoplasms with a monopolar scissors-type knife: short- to long-term outcomes. Endoscopy. 2017;49:913-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yamaguchi T, Kuwai T, Iio S, Tsuboi A, Mori T, Boda K, Yamashita K, Yamaguchi A, Kouno H, Kohno H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using a stag beetle knife for early esophageal cancer in lower esophageal diverticula. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:566-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Takasago T, Kuwai T, Yamaguchi T, Kohno H, Ishaq S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with a scissors-type knife for post-EMR recurrence tumor involving the colon diverticulum (with video). GIE. 2017;2:211–212. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nishimura T, Kuwai T, Yamaguchi T, Kohno H, Ishaq S. Usefulness and safety of a scissors-type knife in endoscopic submucosal dissection for non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (with video). GIE. 2017;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fujinami H, Hosokawa A, Ogawa K, Nishikawa J, Kajiura S, Ando T, Ueda A, Yoshita H, Sugiyama T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms using the stag beetle knife. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nakayama T, Hayashi T, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Takeshima F, Shikuwa S, Kohno S, Nakao K. Usefulness of oral prednisolone in the treatment of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1115-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Predictors of postoperative stricture after esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous cell neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2009;41:661-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mizuta H, Nishimori I, Kuratani Y, Higashidani Y, Kohsaki T, Onishi S. Predictive factors for esophageal stenosis after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:626-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Joo DC, Kim GH, Park DY, Jhi JH, Song GA. Long-term outcome after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center study. Gut Liver. 2014;8:612-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Homma K, Otaki Y, Sugawara M, Kobayashi M. Efficacy of novel SB knife Jr examined in a multicenter study on colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2012;24 Suppl 1:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shiga H, Kuroha M, Endo K, Kimura T, Kakuta Y, Kinouchi Y, Kayaba S, Shimosegawa T. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) performed by experienced endoscopists with limited experience in gastric ESD. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1645-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jeon HH, Lee HS, Youn YH, Park JJ, Park H. Learning curve analysis of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for laterally spreading tumors by endoscopists experienced in gastric ESD. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2422-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ohata K, Nonaka K, Misumi Y, Tsunashima H, Takita M, Minato Y, Tashima T, Sakai E, Muramoto T, Matsuyama Y. Usefulness of training using animal models for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: is experience performing gastric ESD really needed? Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E333-E339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Imai K, Hotta K, Yamaguchi Y, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Takizawa K, Kawata N, Matsubayashi H, Shimoda T, Mori K. Preoperative indicators of failure of en bloc resection or perforation in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: implications for lesion stratification by technical difficulties during stepwise training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:954-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jin XF, Chai TH, Gai W, Chen ZS, Guo JQ. Multiband Mucosectomy Versus Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Treatment of Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia of the Esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:948-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ikeda A, Hoshi N, Yoshizaki T, Fujishima Y, Ishida T, Morita Y, Ejima Y, Toyonaga T, Kakechi Y, Yokosaki H. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) with Additional Therapy for Superficial Esophageal Cancer with Submucosal Invasion. Intern Med. 2015;54:2803-2813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chetty R, Sugimoto M S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y