Published online Feb 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1387

Peer-review started: November 10, 2016

First decision: December 19, 2016

Revised: December 26, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 11, 2017

Published online: February 28, 2017

Processing time: 108 Days and 9 Hours

To characterize colorectal cancer (CRC) in octogenarians as compared with younger patients.

A single-center, retrospective cohort study which included patients diagnosed with CRC at the age of 80 years or older between 2008-2013. A control group included consecutive patients younger than 80 years diagnosed with CRC during the same period. Clinicopathological characteristics, treatment and outcome were compared between the groups. Fisher’s exact test was used for dichotomous variables and χ2 was used for variables with more than two categories. Overall survival was assessed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, with the log-rank test. Cancer specific survival (CSS) and disease-free survival were assessed by the Cox proportional hazards model, with the Fine and Gray correction for non-cancer death as a competing risk.

The study included 350 patients, 175 patients in each group. Median follow-up was 40.2 mo (range 1.8-97.5). Several significant differences were noted. Octogenarians had a higher proportion of Ashkenazi ethnicity (64.8% vs 47.9%, P < 0.001), a higher rate of personal history of other malignancies (22.4% vs 13.7%, P = 0.035) and lower rates of family history of any cancer (36.6% vs 64.6%, P < 0.001) and family history of CRC (14.4% vs 27.3%, P = 0.006). CRC diagnosis by screening was less frequent in octogenarians (5.7% vs 20%, P < 0.001) and presentation with performance status (PS) of 0-1 was less common in octogenarians (71% vs 93.9%, P < 0.001). Octogenarians were more likely to have tumors located in the right colon (45.7% vs 34.3%, P = 0.029) and had a lower prevalence of well differentiated histology (10.4% vs 19.3%, P = 0.025). They received less treatment and treatment was less aggressive, both in patients with metastatic and non-metastatic disease, regardless of PS. Their 5-year CSS was worse (63.4% vs 77.6%, P = 0.009), both for metastatic (21% vs 43%, P = 0.03) and for non-metastatic disease (76% vs 88%, P = 0.028).

Octogenarians presented with several distinct characteristics and had worse outcome. Further research is warranted to better define this growing population.

Core tip: Data regarding octogenarians with colorectal cancer (CRC) are scarce. We compared octogenarians with CRC to younger patients. Octogenarians had a predominance of Ashkenazi ethnicity, a higher rate of personal history of other malignancies and a lower rate of family history of any cancer or of CRC. Their performance status (PS) at presentation was worse and their tumors were more likely to be located in the right colon and to have a poorer differentiation. Octogenarians received less treatment and treatment was less aggressive, regardless of PS. This might contribute to the worse outcome which was found among the octogenarians.

- Citation: Goldvaser H, Katz Shroitman N, Ben-Aharon I, Purim O, Kundel Y, Shepshelovich D, Shochat T, Sulkes A, Brenner B. Octogenarian patients with colorectal cancer: Characterizing an emerging clinical entity. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(8): 1387-1396

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i8/1387.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1387

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death globally[1]. CRC carries an approximately 4.4% lifetime risk and accounts for 8% of all new cancer cases[2]. It is classified according to local invasion depth (T stage), lymph node involvement (N stage), and presence of distant metastases (M stage). These classification are combined into an overall stage scoring from 1 to 4[3], which provides the basis for therapeutic decisions and prognosis[1].

CRC is predominantly associated with the elderly, with an increasing incidence with age. The median age for CRC diagnosis is 68 years, with about 35% of the patients diagnosed above the age of 75 years[2]. Since the elderly population in Western countries constantly grows, the incidence of CRC in octogenarians is expected to increase in the coming years[4]. Clearly, octogenarians are becoming a substantial population among CRC patients.

Currently, the impact of older age on tumor biology and outcome remains unclear. While some studies imply that elderly patients with CRC might have unique features[5-7] as well as worse outcome[7-9], these findings are not consistent[10-13].

Elderly patients are considerably underrepresented in clinical trials[14,15]. Hutchins et al[15] reported that CRC patients who were older than 65 and 70 years accounted for only 40% and 14% of patients in clinical trials, respectively. Furthermore, the cut-off for “elderly” patients with CRC in not consistent across different studies, starting from 65 years of age. Studies evaluating octogenarians are scarce[5,6,16]. At present, as octogenarians are rarely included in clinical trials, their optimal management is not clearly defined.

The aim of this study was therefore to better define this growing entity of elderly patients with CRC. As the median age at diagnosis of CRC is 68[2], similar to some recent studies[5,6,16] we chose a cut-off of 80 years old in order to emphasize age-related characteristics.

This was a retrospective, single center cohort study. The study population included all patients who were 80 years old or older at diagnosis of CRC during the years 2008-2013 and were treated at our institute, a large academic tertiary medical center. This group was matched by year of diagnosis with a control group of consecutive patients younger than 80 years at diagnosis. We assumed this population to be representative of the average CRC population.

The medical records of all patients were reviewed and detailed data on patient demographics, risk factors for CRC, clinical-pathological parameters, treatment, adverse events and outcome were retrieved. Patients’ performance status (PS) at presentation was determined according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale. Staging was defined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging, 7th edition[3]. Grade of toxicity was determined according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0[17]. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

The statistical analysis was generated using SAS software, version 9.4. Fisher’s exact test was used for dichotomous variables and χ2 was used for variables with more than two categories. Overall survival (OS) was assessed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, with the log-rank test. Cancer specific survival (CSS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were assessed by the Cox proportional hazards model, with the Fine and Gray correction for non-cancer death as a competing risk. Cox proportional hazard models were also applied for multivariate analysis and hazard ratios estimations. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Three hundred fifty patients with CRC were included in the study, 175 patients in each group. The clinical characteristics of the two groups are detailed in Table 1. Several significant differences were noted. There were more Ashkenazi Jews (64.8% vs 47.9%) in the octogenarians group and less Arab patients (0% vs 7.1%) or other (1.7% vs 8.3%) ethnicities (P < 0.001). Octogenarians had a higher incidence of second malignancies (22.4% vs 13.7%, P = 0.035) but had lower rates of family history of any cancer (36.3% vs 64.6%, P < 0.001) or CRC (14.4% vs 27.3% P = 0.006). Smoking was less prevalent in octogenarians (24.6% vs 44.3%, P < 0.001), while the incidence of other risk factors, including inflammatory bowel disease, history of polyps and familial CRC syndromes, were comparable between both groups.

| Study cohort | Older (age ≥ 80 yr) | Younger (age < 80 yr) | P value | |

| (n = 350) | (n = 175) | (n = 175) | ||

| Median age (range) | 80 (20-99) | 83 (80-99) | 63 (20-79) | - |

| Male gender | 155 (44.3) | 84 (48) | 71 (40.6) | 0.162 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Ashkenazi | 193 (56.4) | 112 (64.8) | 81 (47.9) | < 0.001 |

| Sephardic | 120 (35.1) | 58 (33.5) | 62 (36.7) | |

| Arab | 12 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 12 (7.1) | |

| Other | 17 (5) | 3 (1.7) | 14 (8.3) | |

| 2nd malignancy | 63 (18.1) | 39 (22.4) | 24 (13.7) | 0.035 |

| Family history of cancer | 157 (51.1) | 53 (36.3) | 104 (64.6) | < 0.001 |

| Family history of CRC | 65 (21.2) | 21 (14.4) | 44 (27.3) | 0.006 |

| IBD | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.335 |

| Polyps2 | 122 (35.4) | 55 (33.2) | 67 (38.5) | 0.233 |

| HNPCC/FAP | 9 (2.7) | 5 (3) | 4 (2.4) | 0.695 |

| Smoking history | 104 (34.9) | 41 (24.6) | 74 (44.3) | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis d/t screening | 45 (12.9) | 10 (5.7) | 35 (20) | < 0.001 |

| Performance status3 of 0-1 | 268 (82.5) | 115 (71) | 153 (93.9) | < 0.001 |

As expected, there was a remarkable difference in CRC diagnosis following screening, with only 5.7% octogenarians diagnosed by screening compared to 20% in the control group (P < 0.001). In addition, octogenarians were less likely to have a PS of 0 or 1 at presentation (71% vs 93.9%, P < 0.001).

Tumor characteristics are depicted in Table 2. Primary tumor location differed between the groups: tumors were located in the right colon in 45.7% of the octogenarians, compared with 34.3% patients in the control group (P = 0.029). At presentation, octogenarians had a higher perforation rate (5.7% vs 1.1%, P = 0.019), while obstruction rates were similar.

| Study cohort | Older (age ≥ 80 yr) | Younger (age < 80 yr) | P value | |

| (n = 350) | (n = 175) | (n = 175) | ||

| Tumor location2 | ||||

| Right colon | 140 (40) | 80 (45.7) | 60 (34.3) | 0.029 |

| Left colon/rectum | 210 (60) | 95 (54.3) | 115 (65.7) | |

| Histology | 0.201 | |||

| NOS | 260 (76.5) | 124 (74.2) | 136 (78.6) | |

| Mucinous | 64 (18.8) | 38 (22.8) | 26 (15) | |

| Signet ring cell | 11 (3.2) | 3 (1.8) | 8 (4.6) | |

| Other | 5 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.78) | |

| Grade3 | 0.025 | |||

| 1 | 48 (14.8) | 17 (10.4) | 31 (19.3) | |

| 2-3 | 276 (85.2) | 146 (89.3) | 130 (80.7) | |

| T | 0.27 | |||

| T1 | 17 (5.2) | 5 (3.1) | 12 (7.4) | |

| T2 | 57 (17.6) | 28 (17.4) | 29 (17.8) | |

| T3 | 237 (73.2) | 123 (76.4) | 114 (69.9) | |

| T4 | 13 (4) | 5 (3.1) | 8 (4.9) | |

| N | 0.357 | |||

| N0 | 179 (67) | 94 (71.2) | 85 (63) | |

| N1 | 56 (21) | 24 (18.2) | 32 (23.7) | |

| N2 | 32 (12) | 14 (10.6) | 18 (13.3) | |

| M1 | 72 (20.7) | 34 (19.8) | 38 (21.7) | 0.655 |

| TNM stage | 0.259 | |||

| I | 65 (19) | 30 (17.7) | 35 (20.2) | |

| II | 116 (33.8) | 66 (38.8) | 50 (28.9) | |

| III | 90 (26.2) | 40 (23.5) | 50 (28.9 ) | |

| IV | 72 (21) | 34 (20) | 38 (22) | |

| LVI | 18 (6) | 11 (7.5) | 7 (4.6) | 0.296 |

| VVI | 36 (11.9) | 15 (10.1) | 21 (13.6) | 0.348 |

| Obstruction4 | 36 (10.3) | 22 (12.6) | 14 (8) | 0.159 |

| Perforation4 | 12 (3.4) | 10 (5.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0.019 |

| Synchronous CRC | 11 (3.1) | 4 (2.3) | 7 (4) | 0.358 |

| Metachronous CRC | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.997 |

| RAS mutated | 8 (22.2) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (26.1) | 0.458 |

| BRAF mutated | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.29 |

| MSI-H | 6 (25) | 3 (100) | 3 (14.3) | 0.001 |

Well differentiated histology (grade 1) was less prevalent in octogenarians (10.4% vs 19.4%, P = 0.025), while other histological characteristics, as well as tumor stage at presentation, were comparable between the groups. With limited genomic data, no apparent differences in RAS and BRAF mutation status were noted. Octogenarians were more likely to have MSI-H (Microsatellite instability- high) status (P = 0.001), but such information was available for only 24 (6.9%) patients.

Significant differences were identified in treatment approach (Table 3). Octogenarians with non-metastatic disease were less likely to receive adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment (27.5% vs 60.9%, P < 0.0001). Even a subset analysis for patients with PS 0-1 demonstrated a lower use of adjuvant/neoadjuvant treatment: 32.6% compared to 61.7% (P < 0.0001). Of all patients treated with chemotherapy, the percentage of octogenarians treated with oxaliplatin-based regimes was also lower compared with younger patients (29.7% vs 59.5%, P = 0.002).

| Study cohort | Older (age ≥ 80 yr) | Younger (age < 80 yr) | P value | |

| No. of LN dissected, mean (SD)2 | 14.4 (6.1) | 14.3 (5.4) | 14.4 (6.8) | 0.893 |

| Adjuvant/neoadjuvant Tx2 | 119/271 (43.9) | 38/138 (27.5) | 81/133 (60.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy2 | 58/116 (50) | 11/37 (29.7) | 47 (59.5) | 0.002 |

| No. of chemotherapy lines in stage IV3 | ||||

| 0 | 12 (20) | 9 (34.6) | 3 (8.8) | 0.016 |

| 1 | 24 (40) | 11 (42.3) | 13 (38.2) | |

| ≥ 2 | 24 (40) | 6 (23.1) | 18 (53) | |

| Type of chemotherapy in stage IV, 1st line34 | 0.239 | |||

| Fluoropyrimidine | 11 (21.6) | 6 (30) | 5 (16.1) | |

| Fluoropyrimidine+oxaliplatin/irinotecan | 40 (78.4) | 14 (70) | 26 (80.9) | |

| Local interventions to metastatic sites5 | < 0.001 | |||

| None | 45 (57) | 28 (90.3) | 17 (35.4) | |

| Surgery ± other local intervention | 31 (39.2) | 2 (6.5) | 29 (60.4) | |

| Other local intervention | 3 (3.8) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (4.2) | |

| Hematological toxicity, grade ≥ 3 | 17 (11) | 4 (8) | 13 (12.5) | 0.404 |

| Non-hematological toxicity, grade ≥ 3 | 37 (23.6) | 9 (18) | 28 (26.7) | 0.261 |

Octogenarians with metastatic disease were treated with fewer chemotherapy lines: 34.6% did not receive any treatment, 42.3% received one line and 23.1% received at least two lines, compared with 8.8%, 38.2% and 53%, respectively, in the control group (P = 0.016). This difference persisted for patients with metastatic disease with PS 0-1: 23.5% octogenarians did not receive any chemotherapy compared to only 7.7% in the control group (P = 0.045). Moreover, octogenarians with metastatic disease underwent local treatment to metastatic sites (including surgery, chemoembolization, stereotactic body irradiation and radiofrequency ablation) less frequently (9.7% vs 65.5%, P < 0.0001).

Chemotherapy in both the adjuvant setting and in patients with metastatic disease had comparable rates of grade 3-5 hematologic and non-hematologic adverse events (Table 3).

The median follow-up time was 40.2 mo (range 1.8-97.5 mo). During this period, 120 patients died of CRC and 230 remained alive or died of other causes. Octogenarians achieved a status of no evidence of disease (NED) less frequently: 88.8% patients with non-metastatic disease and 5.9% of those with metastatic disease achieved NED, compared to 97.8% and 38.9% in the younger patient group (P = 0.003 and P = 0.001, non-metastatic and metastatic disease, respectively).

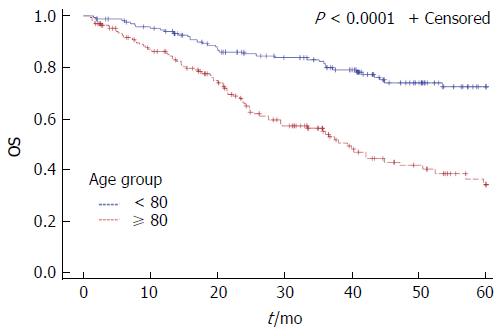

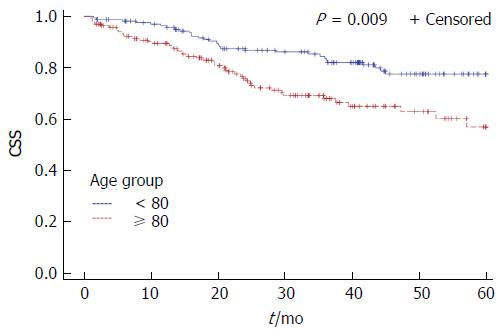

Among patients with non-metastatic disease 5-year DFS rates were 68.7% for octogenarians and 78.7% for younger patients, without reaching statistical significance (P = 0.154). The 5-year OS and CSS rates were worse for octogenarians (5-year OS: 38.5% vs 74.8%, P < 0.0001, 5-year CSS: 63.4% vs 77.6%, P = 0.009) (Figures 1 and 2). Octogenarians had a lower 5-year CSS rate even when the analysis was limited to patients with non-metastatic disease: 76% vs 88% (HR = 2.23, 95%CI: 1.09-4.58, P = 0.028). However, patients with non-metastatic disease who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment had comparable 5-year CSS rates (80% vs 88% for the octogenarians and the control group respectively, P = 0.327). Octogenarians with metastatic disease had a worse 5-year CSS rate: 21% vs 43% (HR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.06-3.25, P = 0.03).

Most “classical” CRC prognostic factors were found to correlate with CSS and DFS on univariate analysis, including T, N, TNM stage, histological subtype of signet ring cell carcinoma, and presentation with obstruction (Table 4). Diagnosis through screening, perforation, PS 0-1 at presentation and grade were associated with CSS, but not DFS. In addition, family history of CRC was associated with better DFS and CSS rates. Patients with metastatic disease who underwent local treatment to metastatic sites also had a better CSS. We performed multivariate analysis for DFS and CSS including age, gender and variables which were found significant in the univariate analysis. TNM stage, histology, family history of CRC and presentation with perforation retained statistical significance on multivariate analysis for CSS (Table 4). TNM stage, histology, family history of CRC and presentation with obstruction were associated with DFS on multivariate analysis. Age was not associated with neither CSS nor with DFS on these multivariate analyses.

| Univariate analysis CSS1 | Multivariate analysis CSS12 | Univariate analysis DFS3 | Multivariate analysis DFS23 | |||||

| 5-yr CSS | P value | Hazard ratio | P value | 5-yr DFS | P value | Hazard ratio | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 63% | 0.009 | 1.7 (0.8-3.6) | 0.155 | 71% | 0.226 | 1.2 (0.5-2.9) | 0.668 |

| ≥ 80 | 78% | 79% | ||||||

| < 80 | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.274 | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 0.762 | 0.682 | 1.1 (0.5-2.2) | 0.865 | ||

| Male | 68% | 77% | ||||||

| Female | 73% | 74% | ||||||

| Ethnicity | 0.293 | - | - | 0.608 | - | - | ||

| Ashkenazi | 73% | 73% | ||||||

| Sephardic | 65% | 78% | ||||||

| Arab | 88% | 69% | ||||||

| Other | 79% | 93% | ||||||

| Second malignancies | 0.497 | - | - | 0.429 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 75% | 81% | ||||||

| No | 70% | 74% | ||||||

| Family hx of cancer | 0.068 | - | - | 0.096 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 78% | 82% | ||||||

| No | 68% | 71% | ||||||

| Family hx of CRC | 0.024 | 0.3 (0.1-0.8) | 0.015 | 0.048 | 0. 2 (0.1-0.8) | 0.016 | ||

| Yes | 86% | 91% | ||||||

| No | 70% | 73% | ||||||

| Performance status | 0.0003 | 1.2 (0.5-3) | 0.62 | 0.068 | 2.1 (0.7-6.3) | 0.175 | ||

| 0-1 | 77% | 78% | ||||||

| 2-4 | 53% | 60% | ||||||

| Mode of Diagnosis | 0.024 | 1 (0.3-3.4) | 0.973 | 0.235 | - | - | ||

| Symptoms | 68% | 74% | ||||||

| Screening | 90% | 85% | ||||||

| Tumor location | 0.102 | - | - | 0.723 | - | - | ||

| Right colon | 66% | 77% | ||||||

| Left colon/rectum | 75% | 75% | ||||||

| Histology | < 0.0001 | 5.7 (1.5-21.1) | 0.009 | < 0.0001 | 6.9 (1.7-28) | 0.007 | ||

| NOS/mucinous/other | 74% | 77% | ||||||

| Signet ring cell | 33% | 48% | ||||||

| Grade | 0.05 | - | - | 0.561 | - | - | ||

| 1 | 87% | 71% | ||||||

| 2-3 | 69% | 76% | ||||||

| T | - | - | - | - | ||||

| T1 | 92% | < 0.0001 | 100% | < 0.0001 | ||||

| T2 | 90% | 82% | ||||||

| T3 | 73% | 72% | ||||||

| T4 | 39% | 76% | ||||||

| N | 0.0003 | - | - | 0.001 | - | - | ||

| N0 | 89% | 81% | ||||||

| N1 | 79% | 72% | ||||||

| N2 | 56% | 57% | ||||||

| M | < 0.0001 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| M0 | 85% | |||||||

| M1 | 26% | |||||||

| TNM stage | < 0.0001 | - | 0.014 | |||||

| I | 94% | 1 | 0.433 | 90% | 1 | - | ||

| II | 90% | 1.9 (0.4-8.7) | 0.013 | 77% | 3.5 (0.8-15.6) | 0.107 | ||

| III | 73% | 6.7 (1.5-30.1) | < 0.0001 | 63% | 8.4 (1.9-36.4) | 0.004 | ||

| IV | 26% | 20 (4.6-87.6) | - | - | - | |||

| LVI | 0.073 | - | - | 0.848 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 57% | 79% | ||||||

| No | 75% | 75% | ||||||

| VVI | 0.272 | - | - | 0.791 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 65% | 72% | ||||||

| No | 75% | 76% | ||||||

| Obstruction | 0.001 | 2.3 (0.99-5.4) | 0.052 | 0.001 | 2.95 (1.1-7.9) | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 49% | 49% | ||||||

| No | 74% | 79% | ||||||

| Perforation | 0.0001 | 3.5 (1.1-10.9) | 0.028 | 0.262 | - | - | ||

| Yes | 28% | 64% | ||||||

| No | 73% | 76% | ||||||

| Adjuvant/neoadjuvant tx | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Yes | 87% | 0.137 | 72% | 0.236 | ||||

| No | 78% | 80% | ||||||

| Local Tx to metastatic sites | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Yes | 41% | 0.007 | ||||||

| No | 20% | |||||||

While the burden of elderly patients with CRC is increasing[2,4], current literature regarding characteristics and optimal management of this subpopulation is unclear. Data are even more limited on the very elderly patients, octogenarians with CRC. In this study, we elected a cut-off of 80 for several reasons. First, the growing number of octogenarians emphasizes the need to explore this population. Second, the cut-off for elderly patients in current literature is inconsistent, starting from 65 years of age, which is clearly not well representative of the nowadays elderly population. Lastly, using a relatively high cut-off may better emphasize the differentiation between the two populations and may elucidate age-dependent differences that might have been masked using a lower cut-off.

In this study, we found a variety of significant differences between octogenarians with CRC and younger patients (“average” patients). Octogenarians had a predominance of Ashkenazi ethnicity, a higher rate of personal history of other malignancies and a lower rate of family history of any cancer or of CRC. In addition, they were less frequently diagnosed by screening; their PS at presentation was worse and their tumors likely to be located in the right colon and to have a poorer differentiation. Moreover, they received less treatment and treatment was less aggressive, both for metastatic and non-metastatic disease, regardless of PS. Not surprisingly, their CSS was worse, both for metastatic and for non-metastatic disease. Some of these findings were described before, and some are novel.

In contrast to other studies[5,6], CRC among octogenarians had no female predominance. The ethnic composition was considerably different between the two groups. There were no Arabs in the octogenarians group as opposed to 7.1% in the control group. This finding is consistent with previous studies which reported a high proportion of Arabs in the young CRC population in Israel[18-20]. The reason for the higher prevalence of Ashkenazi Jews in the elderly group is unclear, although it may at least in part reflect the ethnic distribution in Israel in this age group[21].

Younger patients had a higher prevalence of family history of CRC, a well-established risk factor. In addition, a higher rate of family history of other malignancies in the younger population might represent the presence of other risk factors (for example a family history of endometrial cancer) or even undiagnosed actual cancer-related syndromes. Our finding of better outcome in patients with family history of CRC might be related to better adherence to screening or higher incidence of MMR (mismatch repair) deficiency, which are both associated with better outcome[22-24]. Octogenarians had a higher incidence of secondary malignancies, probably reflecting the increasing incidence of malignancies in the older population[2]. Indeed, most of the other cancer identified in our older group represented other common non-CRC cancers.

As expected, the screening rate was considerably lower among the octogenarians with only 5.7% diagnosed by screening in this group. The higher perforation rate in this population might be related to a lower screening rate. Although the current United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends against routine screening for average risk individuals older than 75[22], current literature regarding the optimal age to discontinue screening is unclear, and it seems that at least some patients might benefit form screening after this age[23,25]. Our findings of low screening rate and worse CSS in octogenarians might further support the need to consider screening for CRC in the elderly, taking into account their life expectancy and comorbidities.

In agreement with previous reports[5-7], we found that octogenarians had clear predilection for right colon tumors. This finding might suggest a distinct pathogenesis of CRC among older patients, such as a higher rate of MMR deficiency or its phenotype, MSI-H tumors. Indeed, we noted, for the first time, that octogenarians had a significantly higher rate of MSI-H tumors. However, as data regarding MSI status were scarce, conclusions from this specific analysis are limited. Since patients with MMR deficiency might benefit from immune check point blockade[26], a routine evaluation of MSI-H status in elderly patients should be considered.

Similarly to earlier studies[16,27,28], octogenarians in the current study were less likely to receive treatment and treatment was less aggressive, both for metastatic and non-metastatic disease. This difference remained statistically significant after adjusting for PS. We could not determine the reason for this finding due to the retrospective nature of this study. As the benefit of both surgery and chemotherapy are well established in CRC[29,30], the worse CSS in the octogenarians in our cohort might be related to the demonstrated avoidance of treatment. Comparable CSS in patients who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment further supports this postulation. Current literature regarding treatment decisions for elderly patients with CRC is conflicting. Alongside reports on the benefit of chemotherapy and surgery in elderly CRC patients[31-38], there are data implying a minimal benefit for oxaliplatin in the adjuvant setting[27,39] and a higher treatment complication rate[28,40] in older patients. In this cohort, there was no difference in chemotherapy associated toxicity. These findings bolster the need for prospective trials aiming to establish the optimal treatment for octogenarians.

Consistent with earlier studies[7-9], octogenarians in our cohort had worse outcome. Nonetheless, as other studies have indicated similar outcomes across different age groups[10-13], the actual impact of age on the outcome of the disease still remains to be established.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective methodology that may cause bias due to unknown or unrecorded confounders. As this is a single center study, it is more vulnerable to such bias. In addition, patients with CRC treated at our tertiary center might not represent the average population with CRC. An additional possible limitation might be a selection bias. Octogenarians included in our study were those referred to an oncologist. Therefore, our cohort might represent more “fit” octogenarians, as other frail octogenarians might have been undiagnosed or were not referred to an oncologist due to their poor clinical status. Nonetheless, the octogenarians in this cohort, who were potentially more “fit” than the average ones, were considerably under-treated compared with younger patients, thus bolstering the validity of this observation. Moreover, data regarding dose reductions were not documented. Therefore, although toxicity rates were comparable between both groups, prospective randomized trials are needed to determine whether toxicity in the older and younger populations is indeed similar. Last, as octogenarians were more likely to have comorbidities and their life expectancy is shorter, conclusions that can be drawn from the difference in survival are limited. However, the difference in CSS was also substantial, implying that octogenarians may indeed have worse outcome.

This study has several strengths. First, it includes a relatively large patient cohort, with a highly representative control group. We found correlations between outcome and most known prognostic factors of CRC, adding to the reliability and validity of the results. Second, as opposed to some large registry-based studies, which might lack important data, we extracted very detailed clinical data from the patients’ individual medical files. Third, in contrast to other studies evaluating elderly patients with CRC which included much lower age cut-off[9,10,12,13,19,27,34,38], this study’s cut-off probably might highlighted the differences between older and the younger population better.

Our study indicates that octogenarians with CRC display several differences in clinical and tumor characteristics, supporting the hypothesis of a unique clinical entity in this population, possibly with a distinct pathogenesis. They were less likely to receive treatment despite adequate PS and their outcome was worse. In light of these findings tailoring the management of octogenarians according to their PS and comorbidities should be further studied. Further research is warranted to better clarify the role of screening for the aging population and to determine well defined treatment guidelines for octogenarians with CRC.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Eitan Amir and Dr. Daliah Galinsky-Tsoref, for their critical contribution of revising this article. Their involvement improved significantly the quality of our manuscript.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is predominantly a disease of the elderly. The incidence of octogenarians with CRC is expected to increase in the coming years. Some studies imply that elderly patients with CRC might represent a unique entity and has worse outcome, but data are not consistent. Although the benefit of chemotherapy and surgery in CRC are well establish, elderly patients often receive less treatment. Octogenarians are becoming a substantial population among CRC patients; but they are rarely included in clinical trials. The authors believe more research is desired to better understand the characteristics and the appropriate management of these patients.

The definition of elderly patients with CRC is inconsistent; some studies used relatively low age cut-off. The authors believe focusing on octogenarians enabled better characterization of the elderly population with CRC and highlighted the differences between elderly patients with CRC compared to the average CRC population. In contrast to registry-based studies, we performed a detailed chart review and extracted data regarding various characteristics, as well as treatment and chemotherapy related adverse events. We found correlation between most known prognostic factors for CRC and outcome, which further supports the validity of this study.

The clinical and pathological differences between octogenarian and the control group suggest CRC in octogenarians might represent a unique clinical entity. Octogenarians were less likely to receive treatment; even if they had good performance status. Chemotherapy treatment was associated with comparable severe adverse events rates. Remarkable worse overall survival and cancer specific survival might imply that avoidance form treatment could contribute to these results.

Older age by itself should not be a contra-indication for oncological treatment. Lack of difference in severe adverse event rates further supports this postulation. In addition, as life expectancy is increasing, screening in fit older population should be considered.

The matter studied in the manuscript is important and needed. The overall structure of the manuscript is clear and complete. The language and methods are appropriate.

| 1. | Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1965] [Cited by in RCA: 2351] [Article Influence: 195.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). Fast Stats. Available from: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. |

| 3. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition. Chicago, Springer, 2010. . |

| 4. | Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374:1196-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2275] [Cited by in RCA: 2296] [Article Influence: 135.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kotake K, Asano M, Ozawa H, Kobayashi H, Sugihara K. Tumour characteristics, treatment patterns and survival of patients aged 80 years or older with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:205-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patel SS, Nelson R, Sanchez J, Lee W, Uyeno L, Garcia-Aguilar J, Hurria A, Kim J. Elderly patients with colon cancer have unique tumor characteristics and poor survival. Cancer. 2013;119:739-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Holt PR, Kozuch P, Mewar S. Colon cancer and the elderly: from screening to treatment in management of GI disease in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:889-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dekker JW, van den Broek CB, Bastiaannet E, van de Geest LG, Tollenaar RA, Liefers GJ. Importance of the first postoperative year in the prognosis of elderly colorectal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1533-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Waldron RP, Donovan IA, Drumm J, Mottram SN, Tedman S. Emergency presentation and mortality from colorectal cancer in the elderly. Br J Surg. 1986;73:214-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mulcahy HE, Patchett SE, Daly L, O’Donoghue DP. Prognosis of elderly patients with large bowel cancer. Br J Surg. 1994;81:736-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fukuchi M, Ishibashi K, Tajima Y, Okada N, Yokoyama M, Chika N, Hatano S, Matsuzawa T, Kumamoto K, Kumagai Y. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients aged 75 years or older with metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4627-4630. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Berretta M, Aprile G, Nasti G, Urbani M, Bearz A, Lutrino S, Foltran L, Ferrari L, Talamini R, Fiorica F. Oxaliplapin and capecitabine (XELOX) based chemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the right choice in elderly patients. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2013;13:1344-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grande C, Quintero G, Candamio S, París Bouzas L, Villanueva MJ, Campos B, Gallardo E, Alvarez E, Casal J, Mel JR; Grupo Gallego de Investigaciones Oncológicas (GGIO). Biweekly XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) as first-line treatment in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4:114-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim JH. Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5158-5166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1739] [Cited by in RCA: 1665] [Article Influence: 61.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kumar R, Jain K, Beeke C, Price TJ, Townsend AR, Padbury R, Roder D, Young GP, Richards A, Karapetis CS. A population-based study of metastatic colorectal cancer in individuals aged ≥ 80 years: findings from the South Australian Clinical Registry for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:722-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE) Publish Date: August 9, 2006. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf. |

| 18. | Neufeld D, Shpitz B, Bugaev N, Grankin M, Bernheim J, Klein E, Ziv Y. Young-age onset of colorectal cancer in Israel. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shemesh-Bar L, Kundel Y, Idelevich E, Sulkes J, Sulkes A, Brenner B. Colorectal cancer in young patients in Israel: a distinct clinicopathological entity? World J Surg. 2010;34:2701-2709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Goldvaser H, Purim O, Kundel Y, Shepshelovich D, Shochat T, Shemesh-Bar L, Sulkes A, Brenner B. Colorectal cancer in young patients: is it a distinct clinical entity? Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:684-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Central Bureau of Statistics. Available from: http://www.cbs.gov.il/shnaton66/st02_06x.pdf. |

| 22. | US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement- colorectal cancer screening. Available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening. |

| 23. | van Hees F, Saini SD, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Vijan S, Meester RG, de Koning HJ, Zauber AG, van Ballegooijen M. Personalizing colonoscopy screening for elderly individuals based on screening history, cancer risk, and comorbidity status could increase cost effectiveness. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1425-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Ma KN, Schaffer D, Coleman LW, Leppert M, Slattery ML. Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:917-923. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Saini SD, Vijan S, Schoenfeld P, Powell AA, Moser S, Kerr EA. Role of quality measurement in inappropriate use of screening for colorectal cancer: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509-2520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6096] [Cited by in RCA: 7491] [Article Influence: 681.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Tournigand C, André T, Bonnetain F, Chibaudel B, Lledo G, Hickish T, Tabernero J, Boni C, Bachet JB, Teixeira L. Adjuvant therapy with fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in stage II and elderly patients (between ages 70 and 75 years) with colon cancer: subgroup analyses of the Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3353-3360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shahir MA, Lemmens VE, van de Poll-Franse LV, Voogd AC, Martijn H, Janssen-Heijnen ML. Elderly patients with rectal cancer have a higher risk of treatment-related complications and a poorer prognosis than younger patients: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3015-3021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Akhtar R, Chandel S, Sarotra P, Medhi B. Current status of pharmacological treatment of colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | André T, Boni C, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Bonetti A, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Rivera F. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109-3116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1502] [Cited by in RCA: 1680] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Golfinopoulos V, Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Treatment of colorectal cancer in the elderly: a review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Papamichael D, Audisio R, Horiot JC, Glimelius B, Sastre J, Mitry E, Van Cutsem E, Gosney M, Köhne CH, Aapro M. Treatment of the elderly colorectal cancer patient: SIOG expert recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:5-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Begg CB. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Neugut AI, Fleischauer AT, Sundararajan V, Mitra N, Heitjan DF, Jacobson JS, Grann VR. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for rectal cancer among the elderly: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2643-2650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kahn KL, Adams JL, Weeks JC, Chrischilles EA, Schrag D, Ayanian JZ, Kiefe CI, Ganz PA, Bhoopalam N, Potosky AL. Adjuvant chemotherapy use and adverse events among older patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1037-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, Macdonald JS, Labianca R, Haller DG, Shepherd LE, Seitz JF, Francini G. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1091-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 768] [Cited by in RCA: 699] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Folprecht G, Seymour MT, Saltz L, Douillard JY, Hecker H, Stephens RJ, Maughan TS, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, Mitry E. Irinotecan/fluorouracil combination in first-line therapy of older and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: combined analysis of 2,691 patients in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1443-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Folprecht G, Cunningham D, Ross P, Glimelius B, Di Costanzo F, Wils J, Scheithauer W, Rougier P, Aranda E, Hecker H. Efficacy of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1330-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Stürmer T, Goldberg RM, Martin CF, Fine JP, McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Niland J, Kahn KL. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival of patients with stage III colon cancer diagnosed after age 75 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2624-2634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Booth CM, Nanji S, Wei X, Mackillop WJ. Management and Outcome of Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases in Elderly Patients: A Population-Based Study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1111-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Israel

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Hoensch HP, Lakatos PL, Wojciechowska J S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF