Published online Feb 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i6.1076

Peer-review started: September 26, 2016

First decision: November 9, 2016

Revised: November 20, 2016

Accepted: December 8, 2016

Article in press: December 8, 2016

Published online: February 14, 2017

Processing time: 142 Days and 0.7 Hours

AIM

To determine whether pain has psycho-social associations in adult Crohn’s disease (CD) patients.

METHODS

Patients completed demographics, disease status, Patient Harvey-Bradshaw Index (P-HBI), Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ), and five socio-psychological questionnaires: Brief Symptom Inventory, Brief COPE Inventory, Family Assessment Device, Satisfaction with Life Scale, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire. Pain sub-scales in P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ measures were recoded into 4 identical scores for univariate and multinomial logistic regression analysis of associations with psycho-social variables.

RESULTS

The cohort comprised 594 patients, mean age 38.6 ± 14.8 years, women 52.5%, P-HBI 5.76 ± 5.15. P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ broadly agreed in their assessment of pain intensity. More severe pain was significantly associated with female gender, low socio-economic status, unemployment, Israeli birth and smoking. Higher pain scores correlated positively with psychological stress, dysfunctional coping strategies, poor family relationships, absenteeism, presenteeism, productivity loss and activity impairment and all WPAI sub-scores. Patients exhibiting greater satisfaction with life had less pain. The regression showed increasing odds ratios for psychological stress (lowest 2.26, highest 12.17) and female gender (highest 3.19) with increasing pain. Internet-recruited patients were sicker and differed from hardcopy questionnaire patients in their associations with pain.

CONCLUSION

Pain measures in P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ correlate with psycho-social pathology in CD. Physicians should be aware also of these relationships in approaching CD patients with pain.

Core tip: Pain is a very important symptom in patients with Crohn’s disease. Pain level and frequency are measurable with a series of simple questionnaires. We show that pain has demographic associations concerning gender, economic status, birthplace and smoking, as well as psycho-social associations such as disease coping strategies, family support, satisfaction with life, absenteeism and presenteeism related to the workplace, and leisure activity. Understanding these relationships will assist physicians in their approach to patients with pain.

- Citation: Odes S, Friger M, Sergienko R, Schwartz D, Sarid O, Slonim-Nevo V, Singer T, Chernin E, Vardi H, Greenberg D, Israel IBD Research Nucleus. Simple pain measures reveal psycho-social pathology in patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(6): 1076-1089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i6/1076.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i6.1076

Crohn's disease (CD) is an idiopathic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly affecting the small and large intestines, and causing diarrhea, pain, malaise, weight loss and anemia. Abdominal pain is the commonest form of pain in patients with CD. It constitutes a major diagnostic criterion of CD in epidemiological studies and the first therapeutic target in CD patient management[1-5]. Over 50% of adult patients with active CD reported having abdominal pain[6,7]. Interestingly, pain is also present when CD is not active. Pain was present in 20% to 50% of patients in clinical remission[1,8,9]. It has been suggested that in these cases the pain results from persistent peripheral sensitization after the acute CD episode has passed, and that this hypersensitivity is augmented by psychological stressors[10]. Concern about pain was reported to be higher in some countries than others; it is reportedly higher in patients in Israel compared to some other countries[11]. Up to a third of patients need to take analgesics for abdominal pain[9]. Medical cannabis is increasingly used to relieve abdominal pain in CD[12]. It was shown that dependence on medication for pain was associated with poorer health status[13]. Pain results in impaired socio-psychological functioning and a reduced quality of life[9,14]. Abdominal pain in CD is associated with depression and increased anxiety[15,16].

The above-quoted studies indicate that while the intensity of pain in CD is a consequence of the pathology of the disease, it is related also to the psychological functioning of these individuals in response to illness-induced stress, and may be moderated by the coping mechanisms used by patients to deal with their illness, and perhaps by demographic variables. These important relationships are as yet poorly understood, and further knowledge in this area may contribute to improving the treatment of these patients. We aimed to investigate the relationship of pain to psychological functioning and disease-coping in the broad spectrum of CD patients of different demographic status. We report here the results of our study performed in a country-wide large non-selected community cohort of CD patients.

Consecutive adult (age 18 years and over) patients consenting to take part in an ongoing socio-economic study of CD in the Israeli adult patient population were studied using self-report questionnaires. Patients were eligible to participate whatever the duration or severity of their illness, and irrespective of their past and present treatments and surgery (if any). There were two methods of patient recruitment. Most patients (70%) were recruited on a consecutive basis when presenting for follow-up or acute non-hospitalized care at the out-patient Gastroenterology Departments of five participating university-affiliated tertiary care hospitals in Israel. These patients met the standard criteria for diagnosis as CD (ECCO), and were given the option of completing the questionnaires on paper or on the internet in their own time at home. The other patients were canvassed on the website of "The Israel Foundation for Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis" and completed the questionnaires on-line. It was assumed that these patients would have established CD. Physicians and nurses did not assist in completing the questionnaires. All questionnaires were in the public domain and were made available in their validated Hebrew translations. Knowledge of Hebrew was a condition for inclusion in the study. Charts of hospital-recruited patients were checked to uncover any psychological or psychiatric disease, but this information could not be ascertained for patients recruited by the internet.

This was a cross-sectional study with data collection from July 2013 to June 2016. Patients reported socio-demographic and medical characteristics including gender, year and place of birth, education, economic status, marital status and number of children, religion and religiosity, current and past smoking habits, disease duration, current medications, anytime surgery for CD, and hospitalizations for CD in the past year. Data concerning co-morbidities were collectible from most patients attending at the hospitals. Patients completed the Patient Harvey-Bradshaw Index (P-HBI), Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ), all of which include questions about pain. In addition, patients completed five socio-psychological questionnaires: Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Brief COPE Inventory (COPE), Family Assessment Device (FAD), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI).

P-HBI[17]: This clinical measure of the severity of disease was specifically designed for patients with CD. It consists of 4 items reflecting the previous day's symptoms and signs of CD; the question regarding the physician's assessment of the possible presence of an abdominal mass in the original HBI is removed in the P-HBI, making the questionnaire suitable for completion by the patients themselves. A total score < 5 indicates disease remission, 5-7 mild disease, 8-16 moderate disease, and > 16 severe disease.

SF-36[18]: This generic health-related quality of life measure is comprised of 36 items divided into eight domains, which in turn are grouped as Physical Health Summary Score (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health) and Mental Health Summary Score (vitality, role-emotional, social functioning, mental health). Responses refer to the past four weeks. The range of the Physical or Mental Health Summary Score is 0-100. A higher score represents a better quality of life. The Hebrew version has been validated[19].

SIBDQ[20]: Is an inflammatory bowel disease-specific health-related quality of life tool measuring physical, social, and emotional status. It consists of 10 items: each item refers to the last two weeks, and is rated on a 7 degree scale (1 = all the time, 7 = never). The total score is in the range from 10-70. A higher value indicates a better quality of life. A validated Hebrew version was used[21].

BSI[22]: This instrument is a measure of psychological stress in the past month. It consists of 53-items that assess nine symptomatic dimensions (depression, somatization, obsession-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism) on a 0-4 scale; a higher score implies more psychological distress. The General Severity Index (GSI) yields a useful global summary score called the GSI with range 0-4. In non-patient normal individuals the GSI was reported as 0.30 ± 0.31. The Hebrew version was validated[23].

Brief COPE Inventory[24]: This measure comprises 28 items; each item is rated on a 4 degree scale (1 = I do not do it at all, 4 = I do it very much). Items are grouped to yield 14 coping subscales that are grouped into 3 strategies: emotion-focused (emotional support use, positive reframing, humor, acceptance, religion), problem-focused (active coping, instrumental support use, planning), and dysfunctional coping (self-distraction, denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement, venting, self-blame). A greater score indicates more use of that coping strategy. The Brief COPE presents the present condition of the subject. We used the validated version in Hebrew[25].

FAD[26]: This is a scale that measures the level of perceptions of family functioning and communication. It consists of 12 items; each item can be rated on a 4 degree scale (1 = strongly agree, 4 = not agree at all). A higher value indicates a worse family functioning. This measure has a Cronbach's Alpha = 0.89. It has been validated in Hebrew[27].

SWLS[28]: This instrument measures the individual's level of satisfaction with life at that moment in time. It includes five questions (q): "q1, my life is close to ideal; q2, conditions of my life are excellent; q3, I am satisfied with my life; q4, I have gotten the important things I want in life; q5, if I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing." Each question is rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not agree at all with the item, 7 = strongly agree). The possible range of this scale is from 1-7 per question. The summary score has a range of 5-35, with a higher value indicating a higher level of satisfaction with life. Cronbach's alpha was 0.89. This measure has been validated in Hebrew[29].

WPAI[30]: This measure evaluates the effect of disease on the patient's ability to work and to perform regular activities in the past 7 d (not including the present day). This instrument yields 4 scores: absenteeism (work time missed due to disease), presenteeism (impairment while working, i.e., reduced on-the-job effectiveness due to disease) work productivity loss (overall work impairment, i.e., the sum of absenteeism plus presenteeism) and activity impairment (degree that disease impairs regular activities). Scores are expressed as percentages. Higher scores indicate greater impairment at work or when performing activities. The Hebrew version of this measure was accessed from the internet[31].

All data from the questionnaires were pooled in a single database. The questions relating to pain were question 2 in P-HBI, question 4 in SIBDQ and question 21 in SF-36. These questions emphasized different aspects of pain and differed by the time period under review and the possible responses. Patients whose data were deemed eligible for analysis were required to have filled in all 3 questions; patients with any missing values were excluded. Based on the frequency of patients' responses to these questions, 4 sub-scores (no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, severe pain) were formulated for each pain scale and used in the analysis (Table 1). Results are expressed as means (± SD), and medians (IQR) where the data distribution was skewed. Univariate analysis was used to show the significance of associations of pain with demographic and socio-psychological variables. We used the Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis test, t-test, and Spearman correlations to test the significance of associations depending on the type of distribution of the data. A multinomial logistic regression was used to examine the associations between the level of pain (in the three scales) and those demographic and socio-psychological variables that were significant on univariate analysis. Each pain questionnaire was examined separately, and the "no pain" state was the reference category. The model controlled for age, education, economic status and family status. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Since the analysis revealed large differences between patients filling in the questionnaires by internet or hardcopy, these results are shown separately.

| Questionnaire | Question about pain | Score in questionnaire | Recoded score |

| Patient Harvey-Bradshaw Index | Did you have abdominal pains yesterday? | 0 None | 0 |

| 1 Mild | 1 | ||

| 2 Moderate | 2 | ||

| 3 Severe | 3 | ||

| MOS Short-Form Survey Instrument | How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 wk? | 1 None | 0 |

| 2 Very Mild | 0 | ||

| 3 Mild | 1 | ||

| 4 Moderate | 1 | ||

| 5 Severe | 2 | ||

| 6 Very Severe | 3 | ||

| Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | How often during the past 2 wk have you been troubled by pain in the abdomen? | 1 All of the time | 3 |

| 2 Most of the time | 2 | ||

| 3 A good bit of the time | 2 | ||

| 4 Some of the time | 1 | ||

| 5 A little of the time | 1 | ||

| 6 Hardly any of the time | 0 | ||

| 7 None of the time | 0 |

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of all participating hospitals and the patients recruited at these hospitals signed an approved informed consent form. Patients recruited via the website were deemed to have consented to participate in the study when they completed the questionnaires electronically. The consent form contained a description of the study, its aims and scope. A similar explanation was posted on the website. All data were treated anonymously.

The total cohort comprised 594 patients with mean age (± SD) 38.6 ± 14.8 years, and 57.6% were women. Duration of disease was 11.05 ± 8.73 years in the entire cohort; 10.8% of patients reported a disease duration of 2 years or less. The P-HBI was 5.76 ± 5.15; 44.6% of the patients were in remission and 55.4% had various grades of active disease. Further demographic data of the cohort are given in Table 2. Very few patients (< 5%) were found to have mild psychological comorbidities and they were included in the analysis since this did not impact on the outcome of the study. In the entire cohort 45.1% of patients were on biologic medication. These patients reported more pain by the P-HBI (P = 0.03) compared with those not on biologic medication. However, there were no differences in respect of the level or frequency of pain by SF-36 or SIBDQ.

| Patient characteristic | Total cohort | Internet questionnaire | Hardcopy questionnaire | P value1 |

| n = 594 | n = 370 | n = 224 | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.151 | |||

| mean ± SD | 38.56 ± 14.06 | 36.99 ± 12.65 | 39.48 ± 14.77 | |

| Median (min-max) (IQR) | 35 (18-79) (28-47) | 35 (18-72) (26 -44) | 35 (19-79) (28-49) | |

| Education (yr) | 0.043 | |||

| mean ± SD | 14.81 ± 2.93 | 15.05 ± 2.65 | 14.66 ± 3.08 | |

| Disease duration (yr) | 0.234 | |||

| mean ± SD | 11.05 ± 8.73 | 10.39 ± 8.23 | 11.45 ± 9.00 | |

| Median (min-max) (IQR) | 10 (0-47) (4-15.5) | 10 (0-41) (3-16) | 10 (0-47) (5-15) | |

| Female gender | 57.6% | 59.78% | 56.90% | 0.521 |

| Married/living together | 58.6% | 57.01% | 60.16% | 0.452 |

| Economic status | ||||

| Good | 29.8% | 25.45% | 33.15% | 0.040 |

| Moderate | 49.8% | 57.27% | 46.58% | |

| Poor | 18.9% | 17.27% | 20.27% | |

| Current cigarette smoking | 18.9% | 16.97% | 21.55% | 0.183 |

| Biologic medication | 45.1% | 44.64% | 45.41% | 0.856 |

| Surgery, ever | 33.3% | 32.59% | 33.78% | 0.765 |

| Hospitalization in past year | 25.3% | 26.79% | 24.32% | 0.503 |

| Patient Harvey-Bradshaw Index (P-HBI) | 5.76 ± 5.15 | 6.70 ± 5.69 | 5.32 ± 4.83 | 0.002 |

| P-HBI sub-groups | ||||

| Disease remission (score < 5) | 44.60% | 66 (40.00%) | 199 (55.74%) | 0.003 |

| Mild disease (score 5-7) | 20.00% | 47 (28.48%) | 72 (20.17%) | |

| Moderate disease (score 8-16) | 19.40% | 40 (24.24%) | 75 (21.01%) | |

| Severe disease (score > 16) | 3.90% | 12 (7.27%) | 11 (3.08%) |

We compared the patients who completed the questionnaires by internet or as hardcopy (Table 2). Internet patients had a lower economic status, higher disease activity level by P-HBI score and worse quality of life compared to the hardcopy patients.

Results of the socio-psychological questionnaires appear in Table 3. In the total cohort the SF-36 summary scores were: physical 42.09 ± 10.76, and mental 41.99 ± 11.33. The SIBDQ total score was 46.33 ± 13.83. Half the patients reported their economic status as moderate. The mean score for satisfaction with life was moderate at 22.06 ± 7.64. The GSI mean score of 0.98 ± 0.75 indicated a mild psychological distress level in the cohort, but the FAD mean score of 1.81 ± 0.55 revealed moderate disturbance of family functioning. Patients made greater use of emotion-focused and dysfunctional coping strategies compared with problem-focused strategies. Concerning the work productivity of the patients, 8.81% reported absenteeism from work and 29.19% reported loss of productivity while at work. Nearly 30% of patients reported overall work impairment, and one third of the patients responded that their disease impaired regular daily activities. The data shown separately for internet and hardcopy patients also appear in Table 3. Significant differences between these groups are noted for quality of life measures, SWLS, GSI, FAD, problem-focused coping, dysfunctional coping, and three of the WPAI measures. Internet patients had lower quality and satisfaction of life scores and more psychological stress compared with hardcopy patients. Internet patients also reported having more problems with family support. Furthermore, internet patients made greater use of problem-focused and dysfunctional coping than hardcopy patients. The internet patients had more absenteeism from work, were less productive and had more activity impairment compared with hardcopy patients.

| Variables | Total cohort | Internet Questionnaire | Hardcopy Questionnaire | P value1 |

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | ||

| Median (min-max) (IQR) | Median (min-max) (IQR) | Median (min-max) (IQR) | ||

| MOS Short-Form Survey Instrument | ||||

| Physical health | 42.09 ± 10.76 | 40.88 ± 10.41 | 42.72 ± 10.90 | 0.041 |

| Mental health | 41.99 ± 11.33 | 39.23 ± 11.36 | 43.42 ± 11.05 | < 0.001 |

| Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, total score | 46.33 ± 13.83 | 42.02 ± 13.38 | 48.84 ± 13.48 | < 0.001 |

| SWLS | 22.06 ± 7.64 | 20.81 ± 7.92 | 22.82 ± 7.37 | 0.004 |

| 23 (5-35) (16-28) | 21.0 (5-35) (15-27) | 24.0 (5-35) (17-29) | ||

| GSI | 0.98 ± 0.75 | 1.11 ± 0.80 | 0.90 ± 0.70 | 0.002 |

| 0.79 (0-3.92) (0.38-1.47) | 0.9 (0.0-3.9) (0.4-1.6) | 0.7 (0.0-3.2) (0.4-1.3) | ||

| FAD | 1.81 ± 0.55 | 1.90 ± 0.56 | 1.75 ± 0.53 | 0.001 |

| 1.75 (1.0-4.0) (1.33-2.17) | 1.9 (1.0-4.0) (1.4-2.3) | 1.7 (1.0-4.0) (1.3-2.1) | ||

| COPE: Emotion-focused strategies | 24.23 ± 5.88 | 24.50 ± 5.77 | 24.07 ± 5.94 | 0.340 |

| 24.5 (3-40) (20-29) | 25 (6-39) (20-29) | 24 (3-40) (20-28) | ||

| COPE: Problem-focused strategies | 16.10 ± 4.74 | 16.82 ± 4.51 | 15.67 ± 4.83 | 0.004 |

| 16 (3-24) (13-20) | 17 (4-24) (14-20) | 16 (3-24) (12-19) | ||

| COPE: Dysfunctional Strategies | 22.28 ± 5.93 | 23.41 ± 5.86 | 21.60 ± 5.87 | 0.000 |

| 22 (6-42) (18-26) | 23 (8-41) (20-27) | 21 (6-42) (17-25) | ||

| WPAI: Absenteeism (%) | 8.81 ± 19.26 | 11.12 ± 20.77 | 7.36 ± 18.16 | 0.021 |

| 0 (0-100) (0-8.35) | 0 (0-100.0) (0-15.2) | 0 (0-100) (0-1.6) | ||

| WPAI: Presenteeism (%) | 29.16 ± 30.20 | 31.52 ± 30.44 | 27.54 ± 30.00 | 0.119 |

| 20 (0-100) (0-50) | 20 (0-100.0) (10.0-55.0) | 20.0 (0-100) (0-50) | ||

| WPAI: Work productivity loss (%) | 29.19 ± 30.38 | 33.60 ± 31.57 | 26.50 ± 29.38 | 0.025 |

| 20 (0-100) (0-50) | 21.2 (0-100) (10-60) | 20.0 (0-100) (0-40.7) | ||

| WPAI: Activity impairment (%) | 33.92 ± 30.61 | 37.60 ± 30.86 | 31.74 ± 30.30 | 0.021 |

| 30 (0-100) (10-60) | 30 (0-100) (10-60) | 20.0 (0-100) (0-50) |

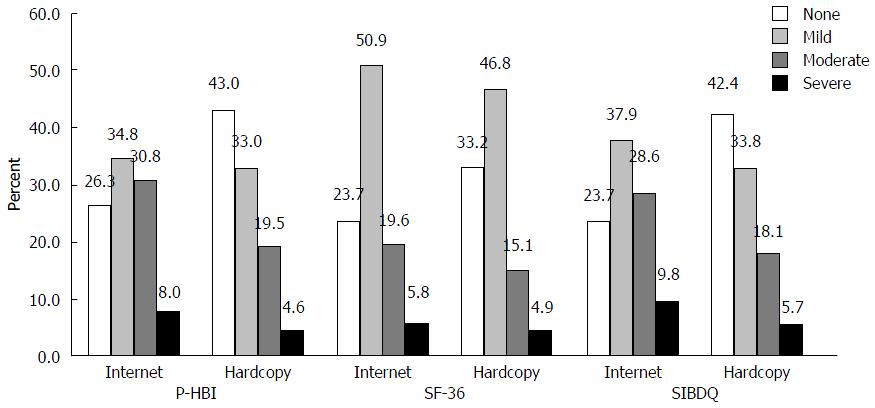

The mean scores (± SD) of the pain questions in the three questionnaires were the following: P-HBI 0.99 ± 0.92, SF-36 52.79 ± 28.44, and SIBDQ 4.46 ± 1.82. The median scores (IQR) of the pain questions were: P-HBI 1 (0-2), SF-36 40 (40-80), and SIBDQ 5 (3-6), respectively. The distribution of the patients' responses to the pain questions (Figure 1) indicated that the responses to P-HBI and SIBDQ were in close agreement, whereas the responses to SF-36 revealed relatively more patients reporting mild pain. Internet patients reported more pain intensity or frequency compared with hardcopy patients with respect to the pain scores by P-HBI and SIBDQ; the differences were statistically significant (both P < 0.001). Demographic variables associated significantly with the degree of reported pain by all three pain measures are shown in Table 4. By the P-HBI measure, females had more frequent moderate and severe pain than males (33.7% vs 24.2%, P = 0.005). Likewise, the P-HBI showed significantly more frequent moderate and severe pain in patient with poorer economic status, birthplace in Israel and not working. By the SF-36 pain measure, a similar result was noted for female gender, poorer economic status, Asia-Africa birthplace and not working. Again, by the SIBDQ pain measure, more frequent moderate and severe pain was noted for poor economic status, birthplace in Israel, current smoker and not working. In Tables 5 and 6 these data are shown separately for the internet and hardcopy patients. It will be noted that the statistically significant differences occur more in the hardcopy part of the cohort.

| Variables | P-HBI | SF-36 | SIBDQ | ||||||||||||

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | |

| Education (yr) | 15.1 ± 2.9 | 14.7 ± 2.8 | 14.8 ± 3.1 | 13.5 ± 3.1 | 0.017 | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 15.0 ± 2.7 | 14.6 ± 3.8 | 14.3 ± 3.1 | 0.463 | 15.1 ± 3.0 | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 14.7 ± 3.0 | 13.3 ± 2.5 | 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.005 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 100 (32.1) | 107 (34.3) | 87 (27.9) | 18 (5.8) | 74 (23.7) | 156 (50.0) | 62 (19.9) | 20 (6.4) | 103 (33.0) | 105 (33.7) | 81 (26.0) | 23 (7.4) | 0.054 | ||

| Male | 103 (45.4) | 69 (30.4) | 40 (17.6) | 15 (6.6) | 88 (38.8) | 106 (46.7) | 25 (11.0) | 8 (3.5) | 96 (42.3) | 76 (33.5) | 39 (17.2) | 16 (7.0) | |||

| Economic status | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Poor | 22 (19.6) | 36 (32.1) | 40 (35.7) | 14 (12.5) | 11 (9.8) | 57 (50.9) | 33 (29.5) | 11 (9.8) | 17 (15.2) | 36 (32.1) | 38 (33.9) | 21 (18.8) | < 0.001 | ||

| Moderate | 105 (35.5) | 110 (37.2) | 65 (22.0) | 16 (5.4) | 96 (32.4) | 150 (50.7) | 39 (13.2) | 11 (3.7) | 112 (37.8) | 104 (35.1) | 64 (21.6) | 16 (5.4) | |||

| Good | 88 (49.7) | 49 (27.7) | 35 (19.8) | 5 (2.8) | 66 (37.3) | 78 (44.1) | 25 (14.1) | 8 (4.5) | 79 (44.6) | 66 (37.3) | 26 (14.7) | 6 (3.4) | |||

| Birthplace | 0.048 | 0.015 | |||||||||||||

| Western | 19 (76.0) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | 12 (48.0) | 9 (36.0) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (12.0) | 19 (76.0) | 4 (16.0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.013 | ||

| Asia-Africa | 14 (43.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (15.6) | 1 (3.1) | 7 (21.9) | 16 (50.0) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0) | 13 (40.6) | 13 (40.6) | 6 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| FSU | 15 (44.1) | 15 (44.1) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (2.9) | 14 (41.2) | 19 (55.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 20 (58.8) | 9 (26.5) | 4 (11.8) | 1 (2.9) | |||

| Israel | 111 (39.9) | 92 (33.1) | 61 (21.9) | 14 (5.0) | 90 (32.4) | 128 (46.0) | 46 (16.5) | 14 (5.0) | 105 (37.8) | 98 (35.3) | 56 (20.1) | 19 (6.8) | |||

| Current smoker | 0.052 | 0.170 | |||||||||||||

| No | 175 (38.5) | 152 (33.5) | 104 (22.9) | 23 (5.1) | 140 (30.8) | 220 (48.5) | 75 (16.5) | 19 (4.2) | 172 (37.9) | 156 (34.4) | 102 (22.5) | 24 (5.3) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 29 (25.9) | 41 (36.6) | 32 (28.6) | 10 (8.9) | 29 (25.9) | 52 (46.4) | 21 (18.8) | 10 (8.9) | 26 (23.2) | 43 (38.4) | 25 (22.3) | 18 (16.1) | |||

| Working | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| No | 61 (32.8) | 51 (27.4) | 51 (27.4) | 23 (12.4) | 40 (21.5) | 86 (46.2) | 45 (24.2) | 15 (8.1) | 60 (32.3) | 53 (28.5) | 50 (26.9) | 23 (12.4) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 152 (39.9) | 140 (36.7) | 77 (20.2) | 12 (3.1) | 130 (34.1) | 183 (48.0) | 52 (13.6) | 16 (4.2) | 147 (38.6) | 143 (37.5) | 74 (19.4) | 17 (4.5) | |||

| Variables | P-HBI | SF-36 | SIBDQ | ||||||||||||

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | |

| Education (yr) | 15.2 ± 2.5 | 15.1 ± 2.5 | 15.0 ± 2.7 | 14.4 ± 3.4 | 0.758 | 14.9 ± 2.7 | 15.2 ± 2.3 | 15.1 ± 2.9 | 13.8 ± 4.2 | 0.397 | 15.1 ± 2.9 | 15.5 ± 2.4 | 14.9 ± 2.6 | 13.6 ± 2.8 | 0.033 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 28 (54.9) | 37 (62.7) | 37 (63.8) | 8 (50.0) | 0.628 | 18 (41.9) | 62 (65.3) | 23 (63.9) | 7 (70.0) | 0.055 | 26 (55.3) | 37 (60.7) | 38 (65.5) | 9 (50.0) | 0.589 |

| Male | 23 (45.1) | 22 (37.3) | 21 (36.2) | 8 (50.0) | 25 (58.1) | 33 (34.7) | 13 (36.1) | 3 (30.0) | 21 (44.7) | 24 (39.3) | 20 (34.5) | 9 (50.0) | |||

| Economic status | |||||||||||||||

| Bad | 4 (6.9) | 12 (16.0) | 16 (23.2) | 6 (33.3) | 0.003 | 2 (3.9) | 18 (15.9) | 12 (27.9) | 6 (46.2) | 0.001 | 2 (3.8) | 13 (15.5) | 12 (19.4) | 11 (50.0) | < 0.001 |

| Medium | 25 (43.1) | 13 (17.3) | 15 (21.7) | 3 (16.7) | 21 (41.2) | 24 (21.2) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (23.1) | 19 (36.5) | 23 (27.4) | 11 (17.7) | 3 (13.6) | |||

| Good | 29 (50.0) | 50 (66.7) | 38 (55.1) | 9 (50.0) | 28 (54.9) | 71 (62.8) | 23 (53.5) | 4 (30.8) | 31 (59.6) | 48 (57.1) | 39 (62.9) | 8 (36.4) | |||

| Current Smoker | |||||||||||||||

| Not Smoking | 52 (91.2) | 62 (81.6) | 53 (76.8) | 14 (87.5) | 0.175 | 44 (84.6) | 95 (84.1) | 33 (80.5) | 9 (75.0) | 0.821 | 46 (90.2) | 70 (83.3) | 49 (79.0) | 16 (76.2) | 0.353 |

| Smoking | 5 (8.8) | 14 (18.4) | 16 (23.2) | 2 (12.5) | 8 (15.4) | 18 (15.9) | 8 (19.5) | 3 (25.0) | 5 (9.8) | 14 (16.7) | 13 (21.0) | 5 (23.8) | |||

| Working | |||||||||||||||

| Not Working | 13 (24.1) | 21 (29.6) | 17 (29.8) | 10 (55.6) | 0.093 | 8 (17.0) | 31 (31.3) | 15 (36.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.044 | 13 (26.0) | 18 (24.3) | 19 (33.3) | 11 (57.9) | 0.033 |

| Working | 41 (75.9) | 50 (70.4) | 40 (70.2) | 8 (44.4) | 39 (83.0) | 68 (68.7) | 26 (63.4) | 6 (46.2) | 37 (74.0) | 56 (75.7) | 38 (66.7) | 8 (42.1) | |||

| Variables | P-HBI | SF-36 | SIBDQ | ||||||||||||

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | |

| Education (yr) | 15.1 ± 3.0 | 14.5 ± 2.9 | 14.5 ± 3.3 | 12.5 ± 2.4 | 0.002 | 14.7 ± 2.7 | 14.8 ± 3.0 | 14.3 ± 4.4 | 14.6 ± 2.0 | 0.411 | 15.1 ± 3.1 | 14.5 ± 3.0 | 14.5 ± 3.3 | 12.9 ± 2.2 | 0.004 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 72 (47.4) | 70 (59.8) | 50 (72.5) | 10 (58.8) | 0.005 | 56 (47.1) | 94 (56.3) | 39 (76.5) | 13 (72.2) | 0.002 | 77 (50.7) | 68 (56.7) | 43 (69.4) | 14 (66.7) | 0.067 |

| Male | 80 (52.6) | 47 (40.2) | 19 (27.5) | 7 (41.2) | 63 (52.9) | 73 (43.7) | 12 (23.5) | 5 (27.8) | 75 (49.3) | 52 (43.3) | 19 (30.6) | 7 (33.3) | |||

| Economic status | |||||||||||||||

| Bad | 18 (11.5) | 24 (20.0) | 24 (33.8) | 8 (47.1) | < 0.001 | 9 (7.4) | 39 (22.7) | 21 (38.9) | 5 (29.4) | < 0.001 | 15 (9.6) | 23 (18.9) | 26 (39.4) | 10 (47.6) | < 0.001 |

| Medium | 76 (48.4) | 60 (50.0) | 27 (38.0) | 7 (41.2) | 68 (55.7) | 79 (45.9) | 16 (29.6) | 7 (41.2) | 81 (51.9) | 56 (45.9) | 25 (37.9) | 8 (38.1) | |||

| Good | 63 (40.1) | 36 (30.0) | 20 (28.2) | 2 (11.8) | 45 (36.9) | 54 (31.4) | 17 (31.5) | 5 (29.4) | 60 (38.5) | 43 (35.2) | 15 (22.7) | 3 (14.3) | |||

| Current Smoker | |||||||||||||||

| Not Smoking | 123 (83.7) | 90 (76.9) | 51 (76.1) | 9 (52.9) | 0.026 | 96 (82.1) | 125 (78.6) | 42 (76.4) | 10 (58.8) | 0.178 | 126 (85.7) | 86 (74.8) | 53 (81.5) | 8 (38.1) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 24 (16.3) | 27 (23.1) | 16 (23.9) | 8 (47.1) | 21 (17.9) | 34 (21.4) | 13 (23.6) | 7 (41.2) | 21 (14.3) | 29 (25.2) | 12 (18.5) | 13 (61.9) | |||

| Working | |||||||||||||||

| Not Working | 48 (30.2) | 30 (25.0) | 34 (47.9) | 13 (76.5) | < 0.001 | 32 (26.0) | 55 (32.4) | 30 (53.6) | 8 (44.4) | 0.003 | 47 (29.9) | 35 (28.7) | 31 (46.3) | 12 (57.1) | 0.007 |

| Working | 111 (69.8) | 90 (75.0) | 37 (52.1) | 4 (23.5) | 91 (74.0) | 115 (67.6) | 26 (46.4) | 10 (55.6) | 110 (70.1) | 87 (71.3) | 36 (53.7) | 9 (42.9) | |||

The results of the five socio-psychological measures were examined in relation to the results of the pain measures (Table 7). More intense pain (moderate and severe pain rather than no pain or mild pain) by P-HBI was noted for GSI, emotion-focused coping strategies, dysfunctional coping strategies, FAD, and all four WPAI analyses. For SF-36 the variables significantly associated with more intense pain were GSI, problem-focused strategies, dysfunctional coping strategies, FAD, and all four WPAI analyses. For the SIBDQ pain measure the significant associations with more intense pain were noted for GSI, dysfunctional coping strategies, FAD, and again all four WPAI analyses. On the other hand, a greater satisfaction with life score was significantly associated with less pain by P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ pain measures (all P < 0.0001). The differences described here in the total cohort occurred in both the hardcopy and internet patients (Tables 8 and 9).

| Variables | P-HBI | SF-36 | SIBDQ | ||||||||||||

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | |

| GSI | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| COPE: Emotion-focused Strategies | 23.4 ± 5.9 | 24.7 ± 5.7 | 25.0 ± 5.8 | 24.2 ± 7.1 | 0.045 | 23.4 ± 5.9 | 24.6 ± 5.9 | 24.2 ± 5.7 | 26.0 ± 5.8 | 0.154 | 23.6 ± 5.9 | 24.8 ± 5.7 | 24.8 ± 5.5 | 23.0 ± 7.3 | 0.059 |

| COPE: Problem-focused Strategies | 15.6 ± 4.9 | 16.1 ± 4.7 | 16.8 ± 4.4 | 16.6 ± 4.9 | 0.249 | 15.4 ± 5.1 | 16.1 ± 4.5 | 16.5 ± 4.5 | 18.2 ± 4.3 | 0.042 | 15.6 ± 5.1 | 16.2 ± 4.7 | 17.0 ± 4.1 | 15.4 ± 4.6 | 0.067 |

| COPE: Dysfunctional Strategies | 20.0 ± 5.5 | 22.9 ± 5.5 | 24.0 ± 5.8 | 25.6 ± 6.6 | < 0.001 | 20.0 ± 5.7 | 22.7 ± 5.7 | 24.0 ± 5.9 | 25.9 ± 5.5 | < 0.001 | 19.9 ± 5.4 | 22.8 ± 5.4 | 24.5 ± 6.0 | 24.6 ± 6.9 | < 0.001 |

| FAD | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.003 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.081 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| SWLS | 24.3 ± 6.6 | 22.0 ± 7.7 | 19.9 ± 7.5 | 17.7 ± 9.8 | < 0.001 | 24.5 ± 6.7 | 22.3 ± 7.1 | 18.4 ± 8.4 | 17.9 ± 9.1 | < 0.001 | 24.8 ± 6.4 | 22.2 ± 7.3 | 19.2 ± 7.4 | 16.9 ± 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Absenteeism | 3.9 ± 11.9 | 5.9 ± 12.4 | 18.2 ± 27.2 | 43.4 ± 37.6 | < 0.001 | 2.8 ± 10.6 | 8.3 ± 18.6 | 21.3 ± 25.2 | 29.4 ± 35.0 | < 0.001 | 1.8 ± 5.5 | 7.8 ± 18.3 | 19.1 ± 22.7 | 38.5 ± 42.2 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Presenteesism | 14.6 ± 22.8 | 29.9 ± 28.0 | 44.4 ± 29.7 | 77.1 ± 26.4 | < 0.001 | 13.0 ± 20.7 | 29.2 ± 26.1 | 55.0 ± 32.9 | 70.7 ± 34.1 | < 0.001 | 10.6 ± 18.2 | 31.6 ± 27.5 | 48.2 ± 29.4 | 69.0 ± 31.1 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Work productivity loss | 15.7 ± 23.3 | 29.5 ± 26.9 | 46.4 ± 32.4 | 80.6 ± 27.1 | < 0.001 | 13.7 ± 20.9 | 30.0 ± 27.0 | 58.6 ± 33.2 | 65.3 ± 35.5 | < 0.001 | 10.2 ± 15.9 | 32.7 ± 27.9 | 52.2 ± 30.9 | 66.6 ± 34.7 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Activity Impairment | 17.1 ± 23.6 | 32.9 ± 26.4 | 51.1 ± 27.9 | 78.3 ± 23.5 | < 0.001 | 14.3 ± 22.0 | 33.4 ± 25.4 | 59.8 ± 27.8 | 76.1 ± 28.8 | < 0.001 | 12.3 ± 19.6 | 34.9 ± 25.4 | 52.7 ± 26.2 | 78.9 ± 24.1 | < 0.001 |

| Variables | P-HBI | SF-36 | SIBDQ | ||||||||||||

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | |

| GSI | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| COPE: Emotion-focused Strategies | 23.4 ± 6.1 | 24.8 ± 5.5 | 25.5 ± 5.6 | 23.2 ± 6.3 | 0.158 | 23.5 ± 6.1 | 24.8 ± 6.0 | 24.7 ± 4.6 | 25.5 ± 5.7 | 0.655 | 24.4 ± 5.6 | 24.3 ± 5.8 | 25.2 ± 5.7 | 23.4 ± 6.5 | 0.525 |

| COPE: Problem-focused Strategies | 15.7 ± 4.8 | 16.8 ± 4.5 | 17.5 ± 4.0 | 18.3 ± 4.8 | 0.096 | 15.8 ± 5.1 | 16.7 ± 4.4 | 17.5 ± 4.0 | 19.7 ± 4.1 | 0.051 | 16.1 ± 4.5 | 16.7 ± 4.8 | 17.7 ± 3.8 | 16.6 ± 5.0 | 0.384 |

| COPE: Dysfunctional Strategies | 20.8 ± 5.8 | 23.4 ± 5.8 | 24.4 ± 5.2 | 27.7 ± 5.4 | < 0.001 | 20.9 ± 5.7 | 23.2 ± 5.8 | 25.4 ± 4.9 | 27.8 ± 5.5 | < 0.001 | 20.9 ± 5.4 | 22.8 ± 5.5 | 24.8 ± 5.8 | 27.4 ± 5.6 | < 0.001 |

| FAD | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 0.116 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.264 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.074 |

| SWLS | 24.1 ± 7.7 | 20.8 ± 7.6 | 19.4 ± 7.3 | 15.5 ± 8.5 | < 0.001 | 24.8 ± 7.7 | 21.2 ± 6.7 | 16.1 ± 7.6 | 16.8 ± 10.4 | < 0.001 | 24.1 ± 7.7 | 21.3 ± 7.3 | 18.6 ± 7.3 | 17.2 ± 9.5 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Absenteeism | 5.2 ± 12.1 | 6.9 ± 12.8 | 17.3 ± 25.2 | 38.1 ± 40.7 | 0.002 | 3.4 ± 9.7 | 11.3 ± 21.7 | 17.1 ± 21.5 | 46.3 ± 35.8 | < 0.001 | 1.6 ± 4.9 | 9.1 ± 18.5 | 18.9 ± 21.1 | 35.4 ± 50.3 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Presenteesism | 15.2 ± 25.8 | 27.1 ± 26.2 | 43.2 ± 26.7 | 76.7 ± 29.6 | < 0.001 | 12.7 ± 17.9 | 31.5 ± 27.8 | 51.4 ± 32.1 | 80.0 ± 24.5 | < 0.001 | 9.1 ± 13.9 | 31.4 ± 29.9 | 44.6 ± 26.4 | 68.0 ± 35.8 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Work productivity loss | 18.0 ± 26.1 | 29.2 ± 26.7 | 47.3 ± 30.3 | 78.2 ± 32.2 | < 0.001 | 15.5 ± 20.6 | 32.6 ± 29.3 | 59.3 ± 32.0 | 78.5 ± 17.5 | < 0.001 | 9.5 ± 14.4 | 32.6 ± 29.4 | 52.2 ± 28.9 | 62.1 ± 42.4 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Activity Impairment | 16.5 ± 23.1 | 34.2 ± 26.2 | 48.6 ± 27.0 | 80.6 ± 25.7 | < 0.001 | 16.3 ± 21.9 | 34.2 ± 26.0 | 62.8 ± 25.4 | 88.0 ± 18.7 | < 0.001 | 11.5 ± 16.4 | 34.2 ± 25.6 | 48.6 ± 25.9 | 82.5 ± 24.5 | < 0.001 |

| Variables | P-HBI | SF-36 | SIBDQ | ||||||||||||

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | P value | |

| GSI | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| COPE: Emotion-focused Strategies | 23.4 ± 5.8 | 24.6 ± 5.8 | 24.5 ± 6.0 | 25.3 ± 7.9 | 0.234 | 23.4 ± 5.9 | 24.4 ± 5.8 | 23.8 ± 6.4 | 26.3 ± 6.0 | 0.302 | 23.3 ± 6.0 | 25.1 ± 5.6 | 24.4 ± 5.3 | 22.5 ± 8.3 | 0.076 |

| COPE: Problem-focused Strategies | 15.6 ± 5.0 | 15.6 ± 4.8 | 16.1 ± 4.7 | 14.6 ± 4.4 | 0.725 | 15.2 ± 5.2 | 15.8 ± 4.6 | 15.8 ± 4.8 | 17.1 ± 4.3 | 0.642 | 15.4 ± 5.3 | 15.8 ± 4.6 | 16.4 ± 4.3 | 14.0 ± 3.8 | 0.192 |

| COPE: Dysfunctional Strategies | 19.8 ± 5.4 | 22.6 ± 5.3 | 23.5 ± 6.4 | 23.1 ± 7.2 | < 0.001 | 19.7 ± 5.7 | 22.3 ± 5.5 | 22.9 ± 6.3 | 24.5 ± 5.1 | < 0.001 | 19.6 ± 5.4 | 22.8 ± 5.3 | 24.1 ± 6.3 | 21.5 ± 7.0 | < 0.001 |

| FAD | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.088 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 0.224 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.016 |

| SWLS | 24.4 ± 6.1 | 22.7 ± 7.6 | 20.3 ± 7.7 | 20.2 ± 10.8 | 0.003 | 24.4 ± 6.3 | 23.0 ± 7.2 | 20.1 ± 8.6 | 18.6 ± 8.2 | 0.002 | 25.1 ± 5.8 | 22.7 ± 7.4 | 19.8 ± 7.5 | 16.5 ± 10.3 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Absenteeism | 3.4 ± 11.9 | 5.3 ± 12.2 | 19.2 ± 29.5 | 57.8 ± 29.1 | < 0.001 | 2.5 ± 11.0 | 6.4 ± 16.0 | 25.6 ± 28.4 | 19.7 ± 33.1 | < 0.001 | 1.8 ± 5.8 | 6.8 ± 18.3 | 19.4 ± 24.8 | 41.1 ± 37.8 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Presenteesism | 14.4 ± 21.4 | 31.5 ± 29.1 | 46.0 ± 33.5 | 78.0 ± 22.8 | < 0.001 | 13.2 ± 22.2 | 27.5 ± 24.6 | 58.3 ± 33.8 | 64.4 ± 39.4 | < 0.001 | 11.2 ± 19.7 | 31.7 ± 25.8 | 53.0 ± 32.6 | 70.0 ± 27.5 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Work productivity loss | 14.8 ± 22.2 | 29.7 ± 27.2 | 45.5 ± 34.9 | 86.1 ± 11.3 | < 0.001 | 12.9 ± 21.2 | 28.3 ± 25.4 | 58.0 ± 34.9 | 57.7 ± 41.9 | < 0.001 | 10.4 ± 16.4 | 32.7 ± 27.0 | 52.3 ± 33.7 | 70.5 ± 29.6 | < 0.001 |

| WPAI: Activity Impairment | 17.3 ± 23.9 | 32.1 ± 26.6 | 53.5 ± 28.6 | 75.7 ± 21.4 | < 0.001 | 13.4 ± 22.1 | 32.8 ± 25.1 | 57.6 ± 29.4 | 69.4 ± 31.7 | < 0.001 | 12.6 ± 20.6 | 35.5 ± 25.4 | 56.3 ± 26.2 | 75.0 ± 23.8 | < 0.001 |

A multinomial logistic regression analysis of demographic and social variables and intensity of pain was carried out. The results of the internet and hardcopy patients are shown separately in Table 10, which is designed in particular to show the differences between these patient groups with regard to the magnitude of the associations. The association was significant for GSI with all three pain measures and for all three results of pain in hardcopy patients, while for internet patients the associations were significant with all measures except mild pain by P-HBI and SF-36. Furthermore, there was a progressive increase in the odds ratio with increasing intensity of pain in all three measures for the internet and hardcopy patients. Female gender too demonstrated a significant association with SF-36 for moderate and severe intensities of pain, likewise with an increasing odds ratio, only for the hardcopy patients. For the P-HBI and SIBDQ measures, however, the regression with female gender was significant only for moderate pain, again limited to hardcopy patients. On regression analysis, the association of dysfunctional coping strategies was significant for mild pain by both P-HBI (OR = 1.07) and SF-36 (OR = 1.07), and for moderate pain by SIBDQ (OR = 1.10), for hardcopy patients. Problem-focused coping in hardcopy patients was associated with all levels of pain by P-HBI. Internet patients did not demonstrate any association of pain and coping strategies at the 5% statistical level, and few associations at the 10% level.

| Characteristic | No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | |||

| InternetOR (P value) | HardcopyOR (P value) | InternetOR (P value) | HardcopyOR (P value) | InternetOR (P value) | HardcopyOR (P value) | ||

| Pain by HBI | |||||||

| GSI | Ref. | 1.74 (0.14) | 2.67 (< 0.001) | 2.89 (0.01) | 6.13 (< 0.001) | 8.51 (< 0.001) | 11.66 (< 0.001) |

| Gender (female) | Ref. | 1.11 (0.80) | 1.63 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.95) | 3.43 (0.00) | 0.76 (0.69) | 2.43 (0.14) |

| Emotion-focused | Ref. | 1.01 (0.81) | 1.04 (0.21) | 1.04 (0.35) | 1.06 (0.15) | 0.96 (0.56) | 1.15 (0.03) |

| Problem-focused | Ref. | 1.04 (0.53) | 0.91 (0.02) | 1.05 (0.44) | 0.91 (0.04) | 1.14 (0.19) | 0.79 (< 0.001) |

| Dysfunctional | Ref. | 1.04 (0.49) | 1.07 (0.04) | 1.02 (0.67) | 1.04 (0.30) | 1.02 (0.76) | 1.01 (0.90) |

| Pain by SF36 | |||||||

| GSI | Ref. | 2.05 (0.07) | 3.22 (< 0.001) | 5.87 (< 0.001) | 6.20 (< 0.001) | 10.12 (< 0.001) | 6.69 (< 0.001) |

| Gender (female) | Ref. | 2.22 (0.05) | 1.42 (0.18) | 2.41 (0.09) | 4.29 (< 0.001) | 3.60 (0.15) | 3.82 (0.03) |

| Emotion-focused | Ref. | 1.01 (0.86) | 1.01 (0.76) | 1.02 (0.71) | 1.04 (0.42) | 1.02 (0.81) | 1.06 (0.35) |

| Problem-focused | Ref. | 1.05 (0.47) | 0.96 (0.32) | 1.11 (0.16) | 0.96 (0.39) | 1.23 (0.10) | 0.97 (0.74) |

| Dysfunctional | Ref. | 1.05 (0.38) | 1.07 (0.05) | 0.98 (0.77) | 1.05 (0.28) | 1.03 (0.73) | 1.07 (0.23) |

| Pain by SIBDQ | |||||||

| GSI | Ref. | 2.39 (0.03) | 4.04 (< 0.001) | 5.57 (< 0.001) | 5.53 (< 0.001) | 6.20 (< 0.001) | 19.91 (< 0.001) |

| Gender (female) | Ref. | 1.16 (0.72) | 1.21 (0.50) | 1.43 (0.44) | 1.93 (0.07) | 0.73 (0.62) | 3.06 (0.08) |

| Emotion-focused | Ref. | 0.97 (0.49) | 1.06 (0.09) | 0.98 (0.72) | 1.01 (0.88) | 0.97 (0.62) | 1.10 (0.14) |

| Problem-focused | Ref. | 1.04 (0.52) | 0.91 (0.01) | 1.08 (0.23) | 0.96 (0.41) | 0.88 (0.21) | 0.79 (< 0.001) |

| Dysfunctional | Ref. | 1.01 (0.91) | 1.06 (0.06) | 1.00 (0.99) | 1.10 (0.01) | 1.11 (0.14) | 0.99 (0.83) |

We have shown in the present study, carried out in a large cohort of CD patients with disease duration of 11 years, that the severity of pain as measured by the questions from the P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ has significant associations with demographic and psycho-social measures. Patients with more intense pain tended to be females, poorer, unemployed, more stressed, less satisfied with life, and Israeli-born rather than immigrants. The pain questions from P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ showed good general agreement in many of these associations. Internet patients had more active disease and lower scores for lower quality of life, and differed in their correlations with pain compared with the hardcopy patients.

Pain is an important symptom in CD patients and features prominently in Patient Reported Outcome scales like the Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and the P-HBI, as well as the health-related quality of life measures SIBDQ and SF-36. While measurement of pain by the patient's subjective response to 4 questions as in the CDAI and the P-HBI has been disputed as to its reliability, it nevertheless remains a widely accepted practice and its brevity makes it quite acceptable to patients. P-HBI and SIBDQ both ask about abdominal pain, which is the commonest form of pain in CD patients, present in about 70% of women and 65% of men[8,32]. SF-36 however enquires about bodily pain, which would include in particular rheumatological pain that is present in 30%-40% of CD cases, particularly in women[8,32]. The recall period of the P-HBI is just one day, adding to its reliability. For the SIBDQ and SF-36 the recall period is longer, 2 and 4 wk respectively. This longer recall period may explain why more patients reported mild pain intensity with SF-36 compared with the other measures. It is also possible that our method of recoding the 6 items in SF-36 to 4 scores corresponding to the questions of P-HBI may account for some of this difference. On the other hand, we recoded the SIBDQ as well, from 7 items to 4 scores, and still its agreement with P-HBI was very good. Thus, the longer recall period may be the explanation: that patients tend to become accustomed to pain over time and discount its intensity. In all, we showed that the combined use of the pain questions from all 3 measures was a useful tool to assess the severity of pain in this CD cohort. The use of the pain questions from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (similar to P-HBI with an additional question regarding the presence or absence of an abdominal mass) and the SIBDQ was previously reported in a study of opiate use in CD patients in the United States, but no attempt was made to standardize these respective scores[33].

Pain in CD is treated with a variety of analgesics including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates and more recently cannabis preparations[12,33,34]. Pain in CD patients is reported as often being undertreated, as was found in a recent large Swiss study[8]. Treatment of pain is often neglected in the patient whose disease is controlled. Unfortunately the ethical limitations of our protocol did not allow of investigation of pain treatments in the cohort.

Predictors of abdominal pain in CD have been little investigated. In a pediatric CD cohort in the United States it was shown by multivariate analysis that pain was predicted by depression, weight loss and abdominal tenderness[14]. However, this cohort was composed entirely of subjects suffering from depression, which is known to exacerbate symptoms like pain in chronic illnesses[35]. In a Scandinavian study performed on distressed adults with CD, use of the SF-36 measure revealed that personality impacted on the pain sub-scale[36]. These two studies did not relate to patients without diagnosed confounding conditions. Our study is the first detailed attempt to our knowledge to unravel the factors that are associated with increased severity of pain in CD patients without psychological or psychiatric comorbidities. By using a self-selected large community cohort presenting all stages of the disease course we were able to investigate patients who are representative of the average patients attending out-patient facilities for on-going medical care. By using a broad spectrum of psycho-social questionnaires we were able to relate the measures of psychological stress, coping strategies, family functioning, satisfaction with life, and functioning at work and at leisure to the intensity of pain captured by the three pain questions. In the univariate analysis, working patients reported less intense pain than those unemployed, and in fact close to 40% of workers had no pain at all. Consistent with this finding, patients with a poorer economic status reported more pain by all three pain measures. Patients with a higher level of satisfaction with life score experienced significantly less pain. In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, stress as measured by the GSI was the variable most related to pain, with the odds ratio increasing progressively as the pain intensity rose. Gender behaved in a fairly similar fashion, with females having more intense pain than males, but with lower odds ratios. These observations show convincingly that the level of stress experienced by patients, as well as gender issues, requires careful clinical consideration in CD cases presenting with pain. It is well known that current smokers have a worse course of CD than non-smokers[37]. Our study adds to this knowledge by the new finding that current smokers experience significantly more pain than non-smokers.

It is well documented that CD patients are less productive than healthy controls and have more periods off work[38]. The literature on this topic has focused in general on the role of medical treatments, particularly the more successful biologic therapy, as well as abdominal surgery in improving the ability of these patients to work. The present study is the first documentation of the association of pain with both work impairment and a lower socioeconomic state. Women are reported to have more severe CD than men[39]. Women with CD also have a reduced quality of life compared with men[40]. Our study however is the first to explore the differences in pain severity and the impact of pain on several psycho-social variables. In healthy individuals and patients with CD there are no gender differences in satisfaction with life[41,42]. The present study indicates that patients with a greater satisfaction of life are healthier, with less pain.

Coping with chronic diseases is an important mental resource to improve patients' well-being, but the variety of measures has resulted in a plethora of concepts regarding coping strategies[43]. We studied disease-coping strategies in relationship to pain using the COPE instrument, which clearly separates emotion-focused, problem-focused and dysfunctional coping strategies and avoids any overlap of component questions[24]. By univariate analysis we found that the dysfunctional coping strategy was significantly correlated with the intensity of pain in all three pain measures. This is not surprising, since this is in fact a negative coping mechanism which does not promote better control of the disease. In the regression analysis we found that dysfunctional coping was associated with mild or moderate pain by all three pain measures. The positively-orientated coping strategies, emotion-focused and problem-focused, showed few correlations with pain intensity. This is contrary to what we expected and the matter requires further investigation. Nevertheless, these findings regarding coping mechanisms present a message for clinicians treating patients with pain: namely, that prompt referral to a psychologist versed in these matters may assist CD patients to cope correctly with their illness and may actually lead to reduction of their pain level, particularly when dysfunctional coping strategies are identified and averted.

The strengths of our study include the use of a large representative cohort and a series of well-accepted psycho-social instruments. The consistencies of the three pain questions demonstrate the validity of this method of assessing pain. One limitation was the use of recall tools, although a recent publication regarding patients with inflammatory bowel disease did find that patient recall was quite adequate for research purposes[44]. The lack of access to detailed clinical material was another limitation. Thus, we could not relate our findings to specific phenotypes of CD by the Montreal classification, nor were we able to document any treatments given for pain and relate them to our research. Furthermore, we could not determine the direction of the reported associations because of the cross-sectional design of our study. Future work should thus include long-term follow up of patients and knowledge of their phenotypic classification and analgesic medication. Moreover, an interventional program will be required to evaluate whether medical and psychological therapy can alleviate pain and its associations in these patients.

In conclusion, the pain questions in the P-HBI, SF-36 and SIBDQ, although differing in their focus, were related a variety of psycho-social pathologies in our CD cohorts. These are associations or correlations and of course cannot imply causality in a cross-sectional study. We suggest that clinicians apply these three simple questions in the busy clinic setting to determine the severity of pain even in those patients who appear to be in remission. In fact, patients could fill in this information in two or three minutes while waiting to be seen. This simple strategy may identify patients in need of psychological treatment.

The following physicians assisted with patient ascertainment: Iris Dotan, Yehuda Chowers, Dan Turner, Abraham Eliakim, Shomron Ben-Horin, Alexander Fich, Arik Segal, Gil Ben-Yakov, Naim Abu-Freha, Daniella Munteanu, Alexander Rozental, Alexander Mushkalo, Nava Gaspar and Vitaly Dizengof.

Pain is a very prominent symptom in Crohn’s disease (CD), and often is very disabling for patients and requires specific medication. Since patients with CD have socio-psychological disturbances, the authors wished to examine whether these have any associations with pain. Authors wished to determine if knowledge of such associations could be useful to the physicians who manage such patients.

Intensive perusal of the literature indicated that subject matter of this article has not been researched previously.

Authors found that the pain questions forming part of three commonly used questionnaires in the clinical assessment of these patients were associated with demographic, social and psychological characteristics in these patients.

The authors suggest that the findings in this study serve as a guide in the clinical and psychological assessment of patients with Crohn’s disease.

The research makes use of a variety of questionnaires which are well known in psychology but are less familiar to physicians. These are described in detail in the methods section of the paper.

The reviewers of this paper have emphasized that pain is only one of several symptoms in these patients, that socio-demographics impact on this symptom, that patients filling in questionnaires by hardcopy or the internet might represent subsets of patients with important social and disease characteristics, that the use of questionnaires in translation requires validation, that medication type could influence the pain symptom and needs to be considered.

| 1. | Bielefeldt K, Davis B, Binion DG. Pain and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:778-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Farrokhyar F, Marshall JK, Easterbrook B, Irvine EJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and mood disorders in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and impact on health. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Wismeijer JA, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:469-474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Agnarsson U, Björnsson S, Jóhansson JH, Sigurdsson L. Inflammatory bowel disease in Icelandic children 1951-2010. Population-based study involving one nation over six decades. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1399-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, D’Haens G, Dotan I, Dubinsky M, Feagan B. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 133.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (116)] |

| 6. | Burkhalter H, Stucki-Thür P, David B, Lorenz S, Biotti B, Rogler G, Pittet V. Assessment of inflammatory bowel disease patient’s needs and problems from a nursing perspective. Digestion. 2015;91:128-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zeitz J, Ak M, Müller-Mottet S, Scharl S, Biedermann L, Fournier N, Frei P, Pittet V, Scharl M, Fried M. Pain in IBD Patients: Very Frequent and Frequently Insufficiently Taken into Account. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Srinath AI, Goyal A, Zimmerman LA, Newara MC, Kirshner MA, McCarthy FN, Keljo D, Binion D, Bousvaros A, DeMaso DR. Predictors of abdominal pain in depressed pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1329-1340. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Morrison G, Van Langenberg DR, Gibson SJ, Gibson PR. Chronic pain in inflammatory bowel disease: characteristics and associations of a hospital-based cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1210-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Spiller RC. Overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27 Suppl 1:48-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, Barbosa A, Marquis P, Moser G, Sperber A, Toner B, Drossman DA. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822-1830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Storr M, Devlin S, Kaplan GG, Panaccione R, Andrews CN. Cannabis use provides symptom relief in patients with inflammatory bowel disease but is associated with worse disease prognosis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:472-480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, Patrick DL. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease health status scales for research and clinical practice. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:104-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hashash JG, Ramos-Rivers C, Youk A, Chiu WK, Duff K, Regueiro M, Binion DG, Koutroubakis I, Vachon A, Benhayon D. Quality of Sleep and Coexistent Psychopathology Have Significant Impact on Fatigue Burden in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Goodhand JR, Wahed M, Mawdsley JE, Farmer AD, Aziz Q, Rampton DS. Mood disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: relation to diagnosis, disease activity, perceived stress, and other factors. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2301-2309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Reigada LC, Hoogendoorn CJ, Walsh LC, Lai J, Szigethy E, Cohen BH, Bao R, Isola K, Benkov KJ. Anxiety symptoms and disease severity in children and adolescents with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bennebroek Evertsz’ F, Hoeks CC, Nieuwkerk PT, Stokkers PC, Ponsioen CY, Bockting CL, Sanderman R, Sprangers MA. Development of the patient Harvey Bradshaw index and a comparison with a clinician-based Harvey Bradshaw index assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:850-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lewin-Epstein N, Sagiv-Schifter T, Shabtai EL, Shmueli A. Validation of the 36-item short-form Health Survey (Hebrew version) in the adult population of Israel. Med Care. 1998;36:1361-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-1578. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Burisch J, Weimers P, Pedersen N, Cukovic-Cavka S, Vucelic B, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Bortlik M, Shonová O, Vind I. Health-related quality of life improves during one year of medical and surgical treatment in a European population-based inception cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease--an ECCO-EpiCom study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1030-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4449] [Cited by in RCA: 4237] [Article Influence: 98.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gilbar O, Ben-Zur H. Adult Israeli community norms for the brief symptom index (BSI). Int J Stress Manag. 2002;9:1-10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3872] [Cited by in RCA: 4263] [Article Influence: 147.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nuttman-Shwartz O, Dekel R. Ways of coping and sense of belonging in the face of a continuous threat. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:667-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster family assessment device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171-180. |

| 27. | Slonim-Nevo V, Mirsky J, Rubinstein L, Nauck B. The impact of familial and environmental factors on the adjustment of immigrants: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;30:92-123. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15130] [Cited by in RCA: 12703] [Article Influence: 635.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Anaby D, Jarus T, Zumbo B. Psychometric evaluation of the Hebrew language version of the satisfaction with life scale. Social Indicators Research. 2010;96:267-274. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1704] [Cited by in RCA: 2306] [Article Influence: 69.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Available from: www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI-ANS_V2_0-Hebrew-Israel.doc. |

| 32. | Schirbel A, Reichert A, Roll S, Baumgart DC, Büning C, Wittig B, Wiedenmann B, Dignass A, Sturm A. Impact of pain on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3168-3177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 33. | Cheung M, Khan S, Akerman M, Hung CK, Vennard K, Hristis N, Sultan K. Clinical markers of Crohn’s disease severity and their association with opiate use. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Naftali T, Mechulam R, Lev LB, Konikoff FM. Cannabis for inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2014;32:468-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Katon W. The impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:215-219. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Boye B, Lundin KE, Leganger S, Mokleby K, Jantschek G, Jantschek I, Kunzendorf S, Benninghoven D, Sharpe M, Wilhelmsen I. The INSPIRE study: do personality traits predict general quality of life (Short form-36) in distressed patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1505-1513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Veloso FT. Clinical predictors of Crohn’s disease course. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:1122-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Büsch K, da Silva SA, Holton M, Rabacow FM, Khalili H, Ludvigsson JF. Sick leave and disability pension in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1362-1377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wagtmans MJ, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hogezand RA. Gender-related differences in the clinical course of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1541-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Saibeni S, Cortinovis I, Beretta L, Tatarella M, Ferraris L, Rondonotti E, Corbellini A, Bortoli A, Colombo E, Alvisi C. Gender and disease activity influence health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel diseases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:509-515. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Clench-Aas J, Nes RB, Dalgard OS, Aarø LE. Dimensionality and measurement invariance in the Satisfaction with Life Scale in Norway. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1307-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sarid O, Slonim-Nevo V, Pereg A. Satisfaction with Life and Coping in Crohn’s Disease: A Gender Perspective (no. 1363). United European Gastroenterology Week: Vienna 2016; . |

| 43. | McCombie AM, Mulder RT, Gearry RB. How IBD patients cope with IBD: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:89-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Randell RL, Long MD, Cook SF, Wrennall CE, Chen W, Martin CF, Anton K, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Validation of an internet-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease (CCFA partners). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:541-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Israel

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C,C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Sanjuan S, Guloksuz S, Lakatos PL S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX