Published online Oct 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i40.7332

Peer-review started: June 3, 2017

First decision: June 22, 2017

Revised: July 10, 2017

Accepted: August 1, 2017

Article in press: August 2, 2017

Published online: October 28, 2017

Processing time: 151 Days and 14.3 Hours

Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis (HTGP) accounts for up to 10% of acute pancreatitis presentations in non-pregnant individuals and is the third most common cause of acute pancreatitis after alcohol and gallstones. There are a number of retrospective studies and case reports that have suggested a role for apheresis and insulin infusion in the acute inpatient setting. We report a case of HTGP in a male with hyperlipoproteinemia type III who was treated successfully with insulin and apheresis on the initial inpatient presentation followed by bi-monthly outpatient maintenance apheresis sessions for the prevention of recurrent HTGP. We also reviewed the literature for the different inpatient and outpatient management modalities of HTGP. Given that there are no guidelines or randomized clinical trials that evaluate the outpatient management of HTGP, this case report may provide insight into a possible role for outpatient apheresis maintenance therapy.

Core tip: There are a number of retrospective studies that have suggested a role for apheresis and insulin infusion in the acute management of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis (HTGP) but the post-discharge course and outpatient management of HTGP remain unclear. We report a case of HTGP in a male with hyperlipoproteinemia type III who was treated successfully with insulin and apheresis on the initial inpatient presentation followed by bi-monthly outpatient maintenance apheresis sessions for the prevention of recurrent HTGP. We also reviewed the literature for the different inpatient and outpatient management modalities of HTGP.

- Citation: Saleh MA, Mansoor E, Cooper GS. Case of familial hyperlipoproteinemia type III hypertriglyceridemia induced acute pancreatitis: Role for outpatient apheresis maintenance therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(40): 7332-7336

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i40/7332.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i40.7332

Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis (HTGP) accounts for up to 10% of acute pancreatitis presentations in non-pregnant individuals and is the third most common cause of acute pancreatitis after alcohol and gallstones[1,2]. Both genetic and secondary causes of lipoprotein metabolism have been implicated in HTGP. A serum triglyceride (TG) level of 10 g/L or greater is associated with acute pancreatitis. The risk of HTGP is approximately 5% with TG levels above 10 g/L and 10% to 20% with TG > 20 g/L[3]. The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines in managing acute pancreatitis recommend obtaining a triglyceride level on all patients with acute pancreatitis without a known history of alcoholism or gallstones. While the ACG guidelines extensively explore the management of pancreatitis in general, there is a lack of data on the specific management of HTGP[4]. A number of retrospective studies and case reports in the past decade have suggested a role for insulin infusion with or without apheresis as an approach to rapidly lowering TG levels in an attempt to treat HTGP[1,5-18]. There are no randomized clinical trials evaluating the benefit of insulin infusion or apheresis in managing HTGP. Furthermore, there is a lack of characterization of post-discharge course and outpatient management of HTGP[19,20]. To our knowledge, there is only one case report of two patients with HTGP in 1996 who were managed with monthly plasmapheresis as maintenance therapy to prevent HTGP recurrence[21]. We report a case of HTGP in a male with hyperlipoproteinemia type III who was treated successfully with insulin and apheresis followed by bi-monthly maintenance apheresis sessions post-discharge as prevention of recurrent HTGP. This case report may provide insight into a possible role for outpatient apheresis maintenance therapy.

A 40-year-old Caucasian male with a past medical history significant for hyperlipoproteinemia type III (on atorvastatin 80 mg daily, fenofibrate 200 mg daily and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids), coronary artery disease status post 3-vessel coronary artery bypass graft, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM) type 2, and one reported episode of acute pancreatitis in the past presented with epigastric pain, nausea and decreased oral intake over 3 d. Physical exam was remarkable for tachycardia to 100 beats/min, localized epigastric tenderness, and xanthomas with striae palmaris. Labs were remarkable for mildly elevated lipase of 334 U/L (reference range 114-286 U/L) and TG levels of 45.3 g/L (reference range 0-149). Abdominal CT scan showed moderate fat stranding around the pancreas and stable pseudocyst. He was started on insulin drip at a rate of 1 unit/h. TG levels trended down after 3 d of insulin infusion to 9.57 g/L. The patient, however, continued to have severe abdominal pain and inability to tolerate oral intake. After 3 d of inpatient stay, patient received his first session of apheresis. After 24 h of apheresis, patient improved symptomatically and was able to tolerate oral intake. Triglyceride levels trended down to 4.61 g/L after 24 h of apheresis and were 6.75 g/L on the day of discharge.

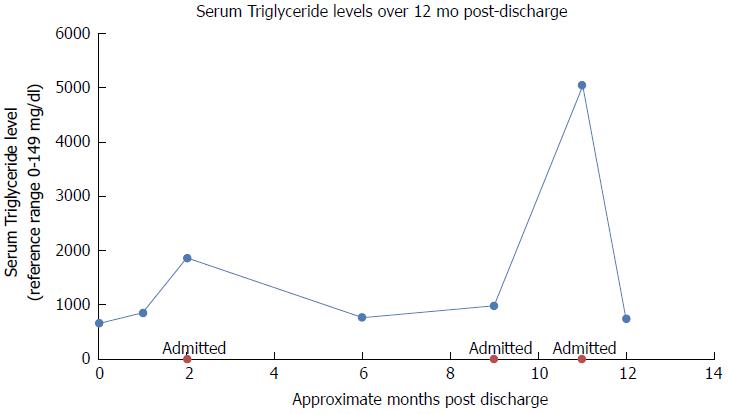

Given that the patient had a complicated cardiac history and that this was his second HTGP presentation in one year, a decision was made to have the patient undergo maintenance apheresis sessions bi-monthly as an outpatient to prevent recurrent pancreatitis and cardiac complications. Patient was discharged on home cardiac medications which consisted of hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily, Plavix 75 mg daily, aspirin 325 mg daily, metoprolol tartrate 50 mg BID, atorvastatin 80 mg daily, fenofibrate 200 mg and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Twelve mo post-discharge course was remarkable for a total of three admissions due to recurrent pancreatitis with one admission attributed to poor adherence to apheresis, fat-free diet and lipid lowering medications. His TG levels mostly remained otherwise successfully below 15 g/L. Repeat abdominal CT scans over 12 mo demonstrated resolution of previous pseudocyst and absence of local complications (Figure 1).

Patients with HTGP present with symptoms typical of acute pancreatitis[1]. Specific features of HTGP that can help identify the etiology include xanthomas on extensor surfaces of arms and legs, lipemia retinalis and hepatosplenomegaly[22]. Lactescent serum is found in 45% of patients with mean Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) level of 4537[2]. A serum TG level of 10 g/L or greater is associated with acute pancreatitis. The risk of HTGP is approximately 5% with TG levels above 10 g/L and 10% to 20% with TG > 20 g/L[23]. HTG by itself is not toxic to the pancreas, however, the breakdown of TG into free fatty acids (FFA) by pancreatic lipase causes lipotoxicity during acute pancreatitis, leading to a systemic inflammatory response[22]. Primary HTG that includes Frederick’s phenotype I-V is associated with HTGP. Our patient was diagnosed with hyperlipoproteinemia type III, an autosomal recessive trait, characterized by presence of Apo E2/E2[24]. Apo E ligand clears chylomicrons and Very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) remnants from the circulation. Thus, this disorder leads to accumulation of VLDL and chylomicrons leading to HTG. Secondary HTG is caused by DM, alcoholism, hypothyroidism, pregnancy, and certain medications such as thiazides, beta blockers, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, immunosuppressants and antipsychotics[1].

A number of retrospective studies and case reports in the past decade suggested a role for insulin infusion with or without apheresis as an approach to rapidly lower TG levels in an attempt to treat HTGP[1,5-18]. There are no randomized clinical trials evaluating the benefit of insulin infusion, heparin or apheresis in managing HTGP to date. However, lowering of TG levels to below 5 g/L has been shown to advance clinical improvement in HTGP[25]. Apheresis is used to lower triglyceride level > 10 g/L and improve signs of severe inflammation such as hypocalcemia and lactic acidosis. One study reported (average TG of 14.06 g/L) a 41% decrease in TGs after one session of plasma exchange[18]. To our knowledge, there is only one case report of two patients with severe HTGP in 1996 who were managed with monthly plasmapheresis maintenance therapy[21]. Their 32-38 mo course was remarkable for only one episode of acute pancreatitis in one patient, suggesting a beneficial role for maintenance plasmapharesis[21].

With regard to anticoagulation during apheresis, studies have shown that citrate as opposed to heparin is associated with decreased mortality[18]. Intravenous insulin has been shown to be more effective than subcutaneous insulin in managing HTGP[26]. Insulin increases lipoprotein lipase which in turn accelerates chylomicron and VLDL metabolism to glycerol and FFA. It also inhibits lipase in adipocytes. Heparin is controversial in efficacy when used alone. It is thought to stimulate the release of endothelial lipoprotein lipase into the circulation, but the mechanism of lowering TG remains unclear[27].

Lipid lowering agents are indicated in the management of HTGP[25]. However, this is further complicated by the association between statin therapy and the development of acute pancreatitis. A series of case-control studies in Taiwan demonstrated that individuals using a statin therapy for the first time are more likely to develop an episode acute pancreatitis when compared to individuals who are not on statin therapy. These studies included Simvastatin (OR = 1.3, 95%CI: 1.02-1.73), Atrovastatin (OR = 1.67, 95%CI: 1.18-2.38), and Rosuvastatin (OR = 3.21, 95%CI: 1.70-6.06)[28-31]. Table 1 provides a summary of HTGP management strategies.

| Management strategy | Description | Indication | Outcomes | Case report/Ref. |

| Diet restriction | Absolute restriction of fat intake | HTG, Primary prevention | Effective when combined with lipid lowering agents[15] | Tsuang et al[15], 2009 |

| Lipid lowering agents | Fibrates (gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily), niacin, N-3 fatty acids, statins | First line in HTG | Triglyceride level lowered about 60% by fibrates, about 50% by niacin, about 45% by omega-3 fatty acids[15] | Tsuang et al[15], 2009 |

| Adjuvant therapy in HTGP | ||||

| Apheresis | Therapeutic Plasma Exchange which is removal of plasma and replacement with colloid solution (albumin, plasma). Citrate is used as an anticoagulant. Goal is TGH < 500 | HTGP without contraindication to Apheresis such as inability to obtain central access or hemodynamic instability | Appears to be effective based on multiple case reports and case series. about 41% decrease in HTG levels. Apheresis within 48 h associated with better outcomes[16] | Furuya et al[16], 2002 |

| Insulin | Intravenous regular insulin drip (0.1 to 0.3 units/kg/h). Goal is TGH < 500. Used alone or in combination with apheresis and/or heparin | Apheresis unavailable unable to tolerate apheresis | Intravenous insulin is more effective than subcutaneous[17] | Berger et al[17], 2001 |

| hyperglycemia > 500 | Effective in lowering triglyceride levels | |||

| Heparin | Combined with insulin. Subcutaneous heparin 500 units BID in 2 case reports | Controversial in HTGP | Controversial. Associated with increased mortality when compared to citrate (both combined with apheresis)[18]. | Gubensek et al[18], 2014 |

| Periodic apheresis | Described in 2 patients as monthly apheresis in 1996 | Recurrence prevention especially in noncompliant patients | Reported success in one case report (2 patients in 1996)[21]. | Piolot et al[21], 1996 |

In summary, we presented a case of HTGP in a male with hyperlipoproteinemia type III who was treated successfully with insulin and apheresis followed by outpatient bi-monthly maintenance apheresis sessions with a 12 mo post-discharge course remarkable for total of three admissions due to recurrent pancreatitis but with TG levels mostly remaining successfully below 15 g/L and repeat abdominal imaging demonstrating resolution of previous pseudocyst and absence of local complications. This may suggest a beneficial role for outpatient apheresis as maintenance therapy in HTGP patients.

A 40-year-old Caucasian male with a past medical history significant for hyperlipoproteinemia type III (on atorvastatin 80 mg daily, fenofibrate 200 mg daily and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids), coronary artery disease status post 3-vessel coronary artery bypass graft, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and one reported episode of acute pancreatitis in the past presented with epigastric pain, nausea and decreased oral intake over 3 d.

Physical exam was remarkable for tachycardia to 100 beats/min, localized epigastric tenderness, and xanthomas with striae palmaris.

Acute pancreatitis, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastroenteritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Labs were remarkable for mildly elevated lipase of 334 U/L (reference range 114-286 U/L) and triglyceride levels of 45.3 g/L (reference range 0-149 g/L).

Abdominal CT scan showed moderate fat stranding around the pancreas and stable pseudocyst.

Insulin, apheresis, atorvastatin 80 mg daily, fenofibrate 200 mg and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

There are a number of case reports in the literature that have demonstrated a benefit from apheresis and insulin therapy in the inpatient management of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis (HTGP). There is only one case report that have suggested a role for outpatient apheresis as a maintenance therapy.

HTGP is acute pancreatitis caused by high levels of serum triglycerides. Apheresis is the process of removal and separation of blood components and replacement with colloid solution (albumin, plasma).

Multiple studies have demonstrated a role for apheresis in the acute management of HTGP. This case report suggests a role for outpatient apheresis in preventing recurrent attacks of HTGP.

This is a nice case report on a timely topic: hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis and role for outpatient apheresis maintenance therapy. This manuscript is generally of interest. The authors provided the complete review of this issue. The manuscript provides the updated evidence to the readers. It can be accepted for publication.

| 1. | Ewald N, Hardt PD, Kloer HU. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and pancreatitis: presentation and management. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:497-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fortson MR, Freedman SN, Webster PD 3rd. Clinical assessment of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2134-2139. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:195-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400-15; 1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1428] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Lim R, Rodger SJ. Hawkins TLA. Presentation and management of acute hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis in pregnancy: A case report. Obstetric Medicine 2015; 200-203. 27512482. |

| 6. | Gavva C, Sarode R, Agrawal D, Burner J. Therapeutic plasma exchange for hypertriglyceridemia induced pancreatitis: A rapid and practical approach. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;54:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takahira S, Suzuki H, Watanabe Y, Kin H, Ooya Y, Sekine Y, Sonoda K, Ogawa H, Nomura Y, Takane H. Successful Plasma Exchange for Acute Pancreatitis Complicated With Hypertriglyceridemia: A Case Report. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2015;3:2324709615605635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Afari ME, Shafqat H, Shafi M, Marmoush FY, Roberts MB, Minami T. Hypertriglyceridemia-Induced Pancreatitis: A Decade of Experience in a Community-Based Teaching Hospital. R I Med J (2013). 2015;98:40-43. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chang CT, Tsai TY, Liao HY, Chang CM, Jheng JS, Huang WH, Chou CY, Chen CJ. Double Filtration Plasma Apheresis Shortens Hospital Admission Duration of Patients With Severe Hypertriglyceridemia-Associated Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2016;45:606-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galán Carrillo I, Demelo-Rodriguez P, Rodríguez Ferrero ML, Anaya F. Double filtration plasmapheresis in the treatment of pancreatitis due to severe hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9:698-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coskun A, Erkan N, Yakan S, Yildirim M, Carti E, Ucar D, Oymaci E. Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis with insulin. Prz Gastroenterol. 2015;10:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | He W, Lu N. Emergent triglyceride-lowering therapy for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2015;62:429-434. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Stefanutti C, Di Giacomo S, Labbadia G. Timing clinical events in the treatment of pancreatitis and hypertriglyceridemia with therapeutic plasmapheresis. Transfus Apher Sci. 2011;45:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tsuang W, Navaneethan U, Ruiz L, Palascak JB, Gelrud A. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: presentation and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:984-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Furuya T, Komatsu M, Takahashi K, Hashimoto N, Hashizume T, Wajima N, Kubota M, Itoh S, Soeno T, Suzuki K. Plasma exchange for hypertriglyceridemic acute necrotizing pancreatitis: report of two cases. Ther Apher. 2002;6:454-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Berger Z, Quera R, Poniachik J, Oksenberg D, Guerrero J. [heparin and insulin treatment of acute pancreatitis caused by hypertriglyceridemia. Experience of 5 cases]. Rev Med Chil. 2001;129:1373-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Gubensek J, Buturovic-Ponikvar J, Romozi K, Ponikvar R. Factors affecting outcome in acute hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis treated with plasma exchange: an observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Athyros VG, Giouleme OI, Nikolaidis NL, Vasiliadis TV, Bouloukos VI, Kontopoulos AG, Eugenidis NP. Long-term follow-up of patients with acute hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:472-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schaap-Fogler M, Schurr D, Schaap T, Leitersdorf E, Rund D. Long-term plasma exchange for severe refractory hypertriglyceridemia: a decade of experience demonstrates safety and efficacy. J Clin Apher. 2009;24:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13:96-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mahley RW, Huang Y, Rall SC Jr. Pathogenesis of type III hyperlipoproteinemia (dysbetalipoproteinemia). Questions, quandaries, and paradoxes. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1933-1949. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Navina S, Acharya C, DeLany JP, Orlichenko LS, Baty CJ, Shiva SS, Durgampudi C, Karlsson JM, Lee K, Bae KT. Lipotoxicity causes multisystem organ failure and exacerbates acute pancreatitis in obesity. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:107ra110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Toskes PP. Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990;19:783-791. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kadikoylu G, Yavasoglu I, Bolaman Z. Plasma exchange in severe hypertriglyceridemia a clinical study. Transfus Apher Sci. 2006;34:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jabbar MA, Zuhri-Yafi MI, Larrea J. Insulin therapy for a non-diabetic patient with severe hypertriglyceridemia. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:458-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Korn ED. Clearing factor, a heparin-activated lipoprotein lipase. I. Isolation and characterization of the enzyme from normal rat heart. J Biol Chem. 1955;215:1. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Liao KF, Huang PT, Lin CC, Lin CL, Lai SW. Fluvastatin use and risk of acute pancreatitis: a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Biomedicine-Taiwan. 2017;7:16-20. |

| 28. | Lin CM, Liao KF, Lin CL, Lai SW. Use of Simvastatin and Risk of Acute Pancreatitis: A Nationwide Case-Control Study in Taiwan. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57:918-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Atorvastatin Use Associated With Acute Pancreatitis: A Case-Control Study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Rosuvastatin and risk of acute pancreatitis in a population-based case-control study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:417-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Liao KF, Tandon RK

S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y