Published online Oct 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i40.7274

Peer-review started: August 17, 2017

First decision: August 30, 2017

Revised: September 19, 2017

Accepted: September 26, 2017

Article in press: September 26, 2017

Published online: October 28, 2017

Processing time: 74 Days and 3.5 Hours

To study differences of presentation, management, and prognosis of alcoholic hepatitis in Latinos compared to Caucasians.

We retrospectively screened 876 charts of Caucasian and Latino patients who were evaluated at University of California Davis Medical Center between 1/1/2002-12/31/2014 with the diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease. We identified and collected data on 137 Caucasians and 64 Latinos who met criteria for alcoholic hepatitis, including chronic history of heavy alcohol use, at least one episode of jaundice with bilirubin ≥ 3.0 or coagulopathy, new onset of liver decompensation or acute liver decompensation in known cirrhosis within 12 wk of last drink.

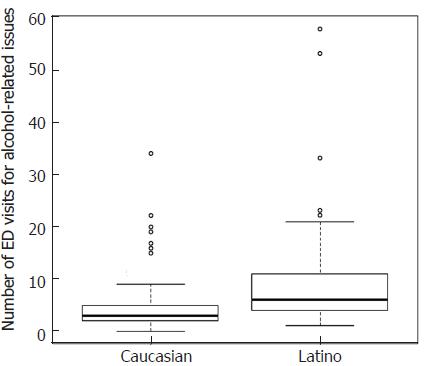

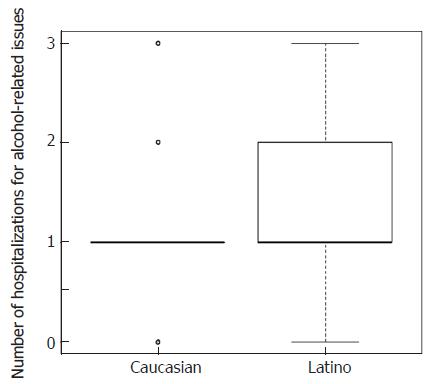

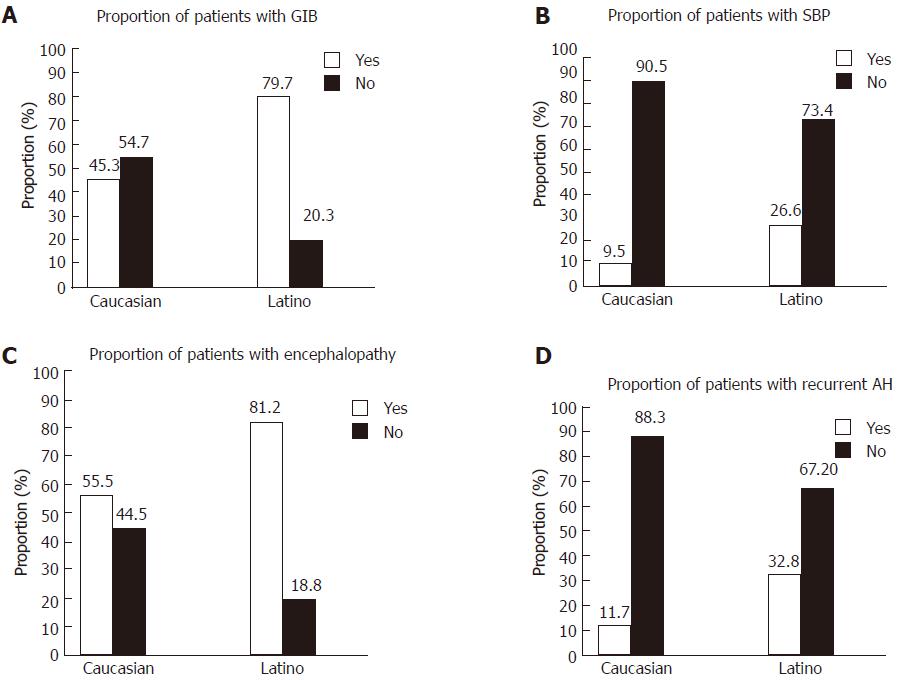

The mean age at presentation of alcoholic hepatitis was not significantly different between Latinos and Caucasians. There was significant lower rate of overall substance abuse in Caucasians compared to Latinos and Latinos had a higher rate of methamphetamine abuse (12.5% vs 0.7%) compared to Caucasians. Latinos had a higher mean number of hospitalizations (5.3 ± 5.6 vs 2.7 ± 2.7, P = 0.001) and mean Emergency Department visits (9.5 ± 10.8 vs 4.5 ± 4.1, P = 0.017) for alcohol related issues and complications compared to Caucasians. There was significantly higher rate of complications of portal hypertension including gastrointestinal bleeding (79.7% vs 45.3%, P < 0.001), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (26.6% vs 9.5%, P = 0.003), and encephalopathy (81.2% vs 55.5%, P = 0.001) in Latinos compared to Caucasians.

Latinos have significant higher rates of utilization of acute care services for manifestations alcoholic hepatitis and complications suggesting poor access to outpatient care.

Core tip: We conducted a retrospective chart review on Caucasian and Latino patients with alcoholic hepatitis. We showed that Latinos had significantly higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding, encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, recurrence of alcoholic hepatitis, and utilization of acute care services for alcohol related issues compared to Caucasians. However, the survival rates were not significantly different between Latinos and Caucasians. Our findings suggest that Latino patients have poor access to outpatient care and management of complications of portal hypertension.

- Citation: Pinon-Gutierrez R, Durbin-Johnson B, Halsted CH, Medici V. Clinical features of alcoholic hepatitis in latinos and caucasians: A single center experience. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(40): 7274-7282

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i40/7274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i40.7274

Alcoholism is estimated to cause 2.5 million deaths annually worldwide, and it represents 4% of all deaths[1]. Forty percent of all mortality from cirrhosis is attributed to alcoholic liver disease (ALD). ALD includes different clinical entities with different severity and prognosis, ranging from alcoholic fatty liver disease characterized by hepatic steatosis, to severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH), and ultimately alcoholic cirrhosis[1] with portal hypertension and its complications. Disparities exist in the incidence and severity of ALD among various racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

Ethnicity data from the National Center for Health Statistics for 1991-1997 showed greatest liver cirrhosis mortality among Latino men compared to Black and Caucasian men followed by Latina females[2]. A comprehensive discharge study of all patients with ALD in non-federal hospitals in Los Angeles County in 1999 showed that ALD accounted for 1.2% of all deaths and was most prevalent in middle aged Latino men as compared to other ethnicities[3]. A more recent study showed that the Latino population in the United States has a higher incidence and more aggressive pattern of chronic liver diseases than the Caucasian population[4]. Longevity data from a multicenter Veteran Affairs cooperative study showed that the 5-year survival from active ALD was only 28% among Latino men compared to 40% in Caucasian men[5]. Among heavy alcohol drinkers, Latinos were 9.1 times more likely to have a 2-fold elevation in AST and GGT levels when compared to Caucasians[6], and Mexican American men are more likely to be heavy binge drinkers than Caucasians and African American men or Mexican American women[7]. A recent review highlights the linkage of excessive alcohol intake and dependence among Mexicans to the presence of functional SNPs in genes that regulate both alcohol craving mechanisms in the brain and alcohol metabolism in the liver[8]. In our own experience[9], Latino patients treated at UC Davis for ALD were significantly younger than Caucasians at the time of presentation and were more likely than Caucasian patients to present with AH or cirrhosis. Despite these well documented differences, there are no ethnic-specific data on the various manifestations of ALD. AH is the most severe manifestation of ALD is characterized by an inflammatory process of the liver with neutrophilic infiltration leading to ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, hepatocyte necrosis, steatosis and presence of Mallory bodies. AH clinic presentation is associated with jaundice, fever, hepatomegaly, liver tenderness, encephalopathy, and gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB)[1]. The goal of the present study was to determine the clinical features of AH in Latino patients compared to Caucasian patients.

We performed a single-center retrospective chart review of 137 Caucasian patients and 64 Latino patients older than 18 years old diagnosed with AH and who were seen at the University of California Davis Hepatology Clinic or hospitalized at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, California between 1/1/2002-12/31/2014. Of note, it is estimated that 83% of Latinos living in the Sacramento area are Mexican Americans (http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06067.html). We performed a chart review of 876 Caucasian and Latino patients with ICD9 codes for AH, alcoholic cirrhosis, ALD, and unspecified liver damage identify subjects with AH of each group. When possible, we applied the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia criteria[10] with few modifications given the retrospective nature of the study: (1) chronic history of heavy alcohol use; (2) at least one episode of jaundice with bilirubin ≥ 3 or coagulopathy with INR ≥ 1.2 (modification); (3) new onset of liver decompensation; (4) diagnosis acute AH per ICD-9 code on known cirrhosis; and (5) within 12 wk (modification) of last drink and where no other causes of liver decompensation were identified. Otherwise, ICD9 codes for AH were applied to ensure the highest number of subjects was included in the study. We excluded patients with known active hepatitis B (positive HBsAg and Hepatitis B viral load > 20,000 IU/mL) and active hepatitis C (positive HCV Ab and HCV viral load > 615 IU/mL).

We used the demographics section of the electronic medical record and/or from history and physical examination notes to identify our research population, ethnicity, gender, and age of onset of AH. We defined the drinking patterns as follow: moderate drinking was defined as no more than four drinks per day, or 14 drinks per week for men, and no more than three drinks per day, or 7 drinks per week for women, and heavy drinking defined as 15 or more drinks per week, or four drinks in a day, for men or, more than seven drinks per week, or three drinks a day for women. We defined binge drinking as five or more drinks for male or 4 or more drinks in female in about 2 h on multiple occasions. We also gathered drinking duration occurred in our patient population. We included data pertaining to body mass index (BMI) and whether subjects had a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus (DM). We recorded the development of complications associated with AH and/or portal hypertension including GIB, encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and presence of other infections, pancreatitis, development of acute kidney injury (AKI) and/or hepatorenal syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), and hepatocellular carcinoma. We recorded intensive care unit (ICU) admission, length of ICU stay, development of respiratory failure, and length of hospital stay, and we determined the number of emergency room visits and hospitalizations for alcohol related morbidity.

We made the distinction of AH without known history of cirrhosis and AH with known cirrhosis and recorded the number of times a patient met our criteria for AH. To assess severity of AH, we calculated the Discriminant Function (DF) [4.6 × (Pt's PT - Control PT) + TBili]. If ≥ 32, it is considered severe AH[11] with related increased risk of mortality[12]. We determined Glasgow score for AH, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class. We collected data on modality of medical treatment of severe AH (supportive care, steroids, pentoxifylline including their duration and doses). Finally, we collected survival data that included total survival days after episode of AH (total number of days since date of AH to last day to be alive or seen at the UC Davis Medical Center or clinic).

Categorical variables were compared between ethnicities using χ2 tests, followed by examination of adjusted residuals in the case of a significant test. Continuous variables were compared between ethnicities using t-tests, with duration data and lab data log-transformed prior to testing. Survival was compared between ethnicities using log rank tests.

The effects of subject disease characteristics and treatment on overall survival were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models. Analyses were conducted for all subjects and separately for each ethnicity. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and, for analyses in all subjects, ethnicity. Analyses were conducted using R, version 3.3.1 (R Core Team, 2016).

The mean age at presentation for all patients was 48.6 ± 10.4 years and was not significantly different between Latinos and Caucasians. Among men, there was a marginally significant higher proportion of male Latino subjects with AH compared to Caucasians subjects (71.9% vs 56.2%, P = 0.049). There were no significant differences between Latinos and Caucasians in BMI, presence of DM, or metabolic syndrome (Table 1). The mean duration of drinking was longer in Latinos compared to Caucasians (24.3 ± 11.0 years vs 20.5 ± 12.7 years, P = 0.027). There were no significant differences between Latinos and Caucasians regarding pattern of drinking or daily mean average number of alcoholic drinks (Table 1). Latinos and Caucasians presented different patterns of non-alcoholic substance abuse. Caucasians had significant higher rates of having no history of substance abuse (73.0% vs 57.8%), whereas more Latinos had a history of methamphetamine abuse (12.5% vs 0.7%) and a remote history of substance abuse (9.4% vs 4.4%) than would be expected under homogeneity of variance (P = 0.003) (Table 1).

| Caucasian (n = 137) | Latino (n = 64) | All Patients (n = 201) | P value | |

| Age of presentation with AH (yr) | 0.082 | |||

| mean ± SD | 49.5 (10.4) | 46.8 (10.1) | 48.6 (10.4) | |

| Sex | 0.049 | |||

| Male | 77 (56.2) | 46 (71.9) | 123 (61.2) | |

| Female | 60 (43.8) | 18 (28.1) | 78 (38.8) | |

| BMI | 0.167 | |||

| mean ± SD | 28.1 (5.9) | 29.4 (6.2) | 28.5 (6) | |

| DM | 0.061 | |||

| No | 105 (76.6) | 41 (64.1) | 146 (72.6) | |

| Yes | 25 (18.2) | 20 (31.2) | 45 (22.4) | |

| Unknown | 7 (5.1) | 3 (4.7) | 10 (5) | |

| Metabolic syndrome | 0.405 | |||

| No | 37 (27) | 13 (20.3) | 50 (24.9) | |

| Yes | 53 (38.7) | 28 (43.8) | 81 (40.3) | |

| Unknown | 47 (34.3) | 23 (35.9) | 70 (34.8) | |

| Duration of drinking (yr) | 0.027 | |||

| mean ± SD | 20 (12.7) | 24.3 (11) | 21.6 (12.3) | |

| Pattern of drinking | 0.283 | |||

| Heavy drinking | 5 (3.6) | 0 | 5 (2.5) | |

| Binge drinking | 130 (94.9) | 64 (100.0) | 194 (96.5) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | |

| Number of drinks/d | 0.093 | |||

| mean ± SD | 13.9 (10.9) | 16.1 (7.2) | 14.6 (9.9) | |

| None | 100 (73.0) | 37 (57.8) | 137 (68.2) | |

| Cocaine | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | |

| Heroin | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| Methamphetamine | 1 (0.7) | 8 (12.5) | 9 (4.5) | |

| Marijuana | 9 (6.6) | 3 (4.7) | 12 (6.0) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | |

| Polysubstance abuse | 10 (7.3) | 9 (14.1) | 19 (9.5) | |

| Remote history | 6 (4.4) | 6 (9.4) | 12 (6.0) | |

| Unknown | 6 (4.4) | 1 (1.6) | 7 (3.5) |

Latinos had about twice the number of emergency department (ED) and hospitalizations visits due to alcohol intoxication and alcohol related issues compared to Caucasians (Figures 1 and 2). There was no significant difference in the mean length of hospital stay between Latinos (52 subjects admitted out of 64) and Caucasians (111 admitted out of 137) admitted to the hospital with AH and there was no significant difference between Latinos and Caucasians requiring ICU admission and length of ICU stay in days (Table 2).

| Caucasian | Latino | All patients | P value | |

| Hospitalization duration (in days) | 111 | 52 | 163 | 0.239 |

| mean ± SD | 14.4 (12.8) | 13.8 (15.9) | 14.2 (13.8) | |

| ICU admission | 111 | 52 | 163 | 0.756 |

| Yes | 39 (35.1) | 17 (32.7) | 56 (34.4) | |

| No | 72 (64.9) | 35 (67.3) | 107 (65.6) | |

| ICU stay (in days) | 39 | 15 | 54 | 0.587 |

| mean ± SD | 7.7 (9.9) | 12.2 (16.6) | 8.9 (12.1) |

There were no significant differences in the proportions of Latinos and Caucasians who presented with AH without history of cirrhosis (76.6% vs 68.6%) and with history of cirrhosis (23.4% vs 31.4%) (P = 0.321). The mean DF score of the whole group was 46.7 ± 33.9 and there was no significant difference in prevalence of severe AH, as determined by DF > 32, between Latinos and Caucasians, mean MELD score, and initial mean Glasgow score for AH (Table 3). Among patients who received medical treatment for severe AH (Latinos n = 15 and Caucasians n = 37), patients from both ethnicities were treated similarly with similar proportions of patients treated with steroids, pentoxyfilline or combination of both (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the Lille score after 7 d of treatment between Latinos (n = 14) and Caucasians (n = 35) (Table 3).

| Caucasian | Latino | All patients | P value | |

| Type of AH | 137 | 64 | 201 | 0.321 |

| Acute AH with no history of cirrhosis | 94 (68.6) | 49 (76.6) | 143 (71.1) | |

| AH on chronic cirrhosis | 43 (31.4) | 15 (23.4) | 58 (28.9) | |

| DF score at day 0 | 137 | 64 | 201 | 0.794 |

| mean ± SD | 47.7 (37.2) | 46.6 (22.1) | 47.3 (33.1) | |

| DF < 32 | 44 (32.1) | 12 (18.8) | 56 (27.9) | |

| DF > 32 | 93 (67.9) | 52 (81.2) | 145 (72.1) | |

| Initial MELD score | 137 | 64 | 201 | 0.661 |

| mean ± SD | 21.1 (7) | 21.6 (6.7) | 21.3 (6.9) | |

| < 9 | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| 10-19 | 61 (44.5) | 30 (46.9) | 91 (45.3) | |

| 20-29 | 53 (38.7) | 25 (39.1) | 78 (38.8) | |

| 30-39 | 19 (13.9) | 9 (14.1) | 28 (13.9) | |

| > 40 | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | |

| Glasgow AH score at day 0 | 0.991 | |||

| mean ± SD | 7.5 (1.6) | 7.4 (1.5) | 7.5 (1.6) | |

| < 9 | 109 (71.7) | 53 (69.7) | 162 (71.1) | |

| > 9 | 43 (28.3) | 23 (30.3) | 66 (28.9) | |

| Type of treatment | 37 | 15 | 52 | 0.862 |

| Steroids | 16 (11.7) | 8 (12.5) | 24 (11.9) | |

| Pentoxifylline | 13 (9.5) | 4 (6.2) | 17 (8.5) | |

| Both | 8 (5.8) | 3 (4.7) | 11 (5.5) | |

| Lille score after 7 d | 0.829 | |||

| < 0.45 | 18 (13.1) | 8 (12.5) | 26 12.9) | |

| > 0.45 | 17 (12.4) | 6 (9.4) | 23 (11.4) |

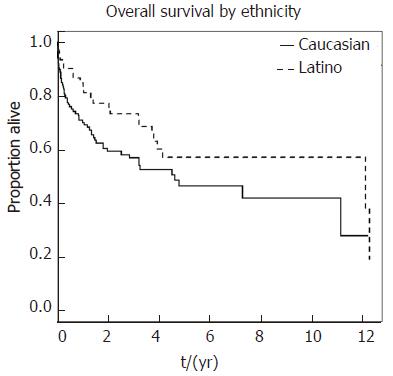

Latinos and Caucasians admitted with AH presented a similar rate of complications including respiratory failure, acute pancreatitis, AKI, hepatorenal syndrome, and DIC (Table 4). However Latinos had higher rates of portal hypertension complications including overall GIB (Figure 3A), SBP (Figure 3B), encephalopathy (Figure 3C), and recurrence of AH (Figure 3D) compared to Caucasians. Despite these higher rates of complications, Latinos presented a longer median survival compared to Caucasians but the difference was not significant (12.1 vs 4.6 years, P = 0.055) (Figure 4).

| Caucasian | Latino | All patients | P value | |

| Development of respiratory failure | 137 | 64 | 201 | 0.687 |

| Yes | 13 (9.5) | 8 (12.5) | 21 (10.4) | |

| No | 124 (90.5) | 56 (87.5) | 180 (89.6) | |

| Development of acute pancreatitis | 0.413 | |||

| No | 110 (80.3) | 52 (81.2) | 162 (80.6) | |

| Yes | 13 (9.5) | 3 (4.7) | 16 (8.0) | |

| Unknown | 14 (10.2) | 9 (14.1) | 23 (11.4) | |

| Development of AKI | 0.520 | |||

| Yes | 33 (24.1) | 19 (29.7) | 52 (25.9) | |

| No | 104 (75.9) | 45 (70.3) | 149 (74.1) | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 0.328 | |||

| No | 119 (86.9) | 60 (93.8) | 179 (89.1) | |

| Yes, type 1 | 15 (10.9) | 3 (4.7) | 18 (9.0) | |

| Yes, type 2 | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (2.0) | |

| Development of DIC | 0.497 | |||

| Yes | 3 (2.2) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | |

| No | 89 (65) | 50 (78.1) | 139 (69.2) | |

| Unknown | 45 (32.8) | 14 (21.9) | 59 (29.4) |

Table 5 shows results of Cox proportional hazards analysis of overall survival. In the analysis of all subjects, after adjusting for age, BMI, sex, and ethnicity, a higher MELD score, a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of C, an initial Maddrey score > 32, abnormal renal function, and presence of hepatorenal syndrome were all associated with significantly higher hazards of death. In Latinos, after adjusting for age, BMI, and sex, a higher MELD score, a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of C, an initial Glasgow score above 9, and the presence of hepatorenal syndrome were associated with significantly higher hazards of death. In Caucasian subjects, after adjusting for age, BMI, and sex, a higher MELD score, a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of C, abnormal renal function, and presence of hepatorenal syndrome were associated with significantly higher hazards of death.

| All subjects | Caucasian subjects | Latino subjects | ||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| History of GI bleeding: yes vs no | 0.79 (0.49, 1.28) | 0.339 | 0.91 (0.53, 1.54) | 0.718 | 0.39 (0.09, 1.72) | 0.213 |

| History of SBP: yes vs no | 0.95 (0.50, 1.80) | 0.874 | 0.86 (0.37, 2.01) | 0.727 | 0.98 (0.37, 2.62) | 0.97 |

| ICU Admission: yes vs No | 1.32 (0.80, 2.19) | 0.278 | 1.42 (0.79, 2.56) | 0.237 | 1.31 (0.45, 3.81) | 0.618 |

| MELD score2 | 1.88 (1.39, 2.55) | < 0.001 | 1.86 (1.29, 2.69) | 0.001 | 2.15 (1.19, 3.87) | 0.011 |

| Child-turcotte-pugh score: C vs A or B | 2.85 (1.62, 5.00) | < 0.001 | 2.62 (1.36, 5.07) | 0.004 | 4.3 (1.24, 14.9) | 0.021 |

| Initial glasgow score: > 9 vs < 9 | 1.86 (1.18, 2.93) | 0.008 | 1.6 (0.93, 2.74) | 0.091 | 2.91 (1.21, 6.97) | 0.017 |

| Initial maddrey score: > 32 vs < 32 | 2.41 (1.29, 4.49) | 0.006 | 1.82 (0.95, 3.50) | 0.072 | 3 | 3 |

| Treatment with steroids: yes vs no | 1.63 (0.89, 2.98) | 0.113 | 1.68 (0.81, 3.51) | 0.164 | 2.05 (0.61, 6.88) | 0.247 |

| Duration of treatment with steroids: ≥ 28 d vs < 28 d | 2.23 (0.66, 7.58) | 0.198 | 5.28 (0.69, 40.5) | 0.110 | 1.03 (0.01, 83.3) | 0.988 |

| Renal function: CKD 1 or higher vs CKD 0 | 7.43 (2.74, 20.1) | < 0.001 | 7.74 (2.8, 21.4) | < 0.001 | 3 | 3 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome: yes vs no | 7.07 | < 0.001 | 7.77 | < 0.001 | 5.65 | 0.006 |

| (3.95, 12.7) | (3.92, 15.4) | (1.66, 19.2) | ||||

AH is an acute hepatic inflammation that usually occurs in heavy drinkers and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in severe cases of up to 30%-50% at 6 mo[13]. Several previous studies indicated that Latino patients with ALD had earlier onset of disease and poorer prognosis compared to Caucasians[9] but specific data on ALD subtypes are lacking. The goal of the present study was to focus on a sample of Latino patients with AH followed at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, California and describe any similarities and differences of AH in comparison to Caucasian patients, with the ultimate goal to identify specific needs and potential gaps in the care of this population. First, Latinos and Caucasians appeared to differ primarily in the duration of alcohol drinking, which was longer for the Latinos, and methamphetamine use, which was also more prevalent in Latinos. These findings are corroborated by previous large epidemiological studies showing that Mexican migrants in California presented a high prevalence of methamphetamine use associated with alcohol use and other psychiatric issues[14]. The two groups received similar medical treatment once admitted for severe AH. However, Latinos appear to present more frequently with manifestations of severe portal hypertension in association with more frequent utilization of the acute services but not ICU. Overall, these disparities did not seem to affect the survival of our studied Latino population. Several clinical studies indicate that Latinos develop more severe liver diseases than other ethnicities and this has been confirmed in common conditions including ALD[9,15], non-alcoholic steatohepatitis[16], and chronic hepatitis C[17,18] or more rare diseases including primary biliary cholangitis[19]. In addition, Latinos might have an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma[20]. Ethnic matching between patients with alcohol-related injury or alcohol problems improved the effectiveness of the brief alcohol intervention on drinking outcomes of Latino patients, especially the foreign-born and less acculturated[21]. Our data indicate that, at least in our center, Latinos with AH are receiving similar inpatient medical management compared to Caucasians. It should be noted that only a small number of patients received treatment for severe AH during the studied period. This could be related to the presence of contraindications to the use of steroids (for example active infections or GIB) or to the lack of proper diagnosis of severe AH by providers. The main issue regards the long term management of the complications of portal hypertension. Previous published data have shown that Latinos are more likely to visit the ED and are more often admitted through the ED for alcohol related issues[22]. Similarly, our study showed that Latinos present more frequently at the ED and are hospitalized more often compared to Caucasians for alcohol related issues, but also present more frequently severe complications of portal hypertension. This suggests a poor outpatient management of chronic complications of liver disease and inadequate access or use of outpatient clinics to receive preventive measures, including GIB prophylaxis with upper endoscopies and beta blockers, encephalopathy prophylaxis with lactulose, or prophylaxis with SBP when indicated. We did not observe any difference in survival between the two subpopulations and this may be in contradiction with the data showing worse outcome for Latinos with ALD. It is also interesting to note that the overall Latino population has better survival rate compared to Caucasians[23]. Our data reflect a small population in a highly diverse urban area but this initial data should help in identifying some of the major challenges in the care of underserved populations. Given the retrospective nature of the data collection and given the fact that is based on single center experience, we could not identify the actual background of the Latino population, which could be very heterogeneous.

This single retrospective study did not confirm previous findings that Latinos developed AH at earlier age compared to Caucasians[9]. In fact, there was no significant difference between the ages of presentation of AH between Latinos and Caucasians. Our study also suggested that there is no difference in the severity of AH at presentation and management between the ethnicities. On the other hand, this study showed Latinos had higher rates of complications associated with AH which include GIB, encephalopathy, and SBP. Latinos also had higher rates of AH recurrence. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the overall mortality between ethnicities. In fact, Latinos may have better survival than Caucasians even though this is was not statistically significant in our study. Future research is needed to elucidate the effects of alcohol on Latinos and the predisposing factor that lead to the development of AH as well as the study of measures that can improve access to care and adequate outpatient follow-up for this underserved population.

There are well known differences in the presentation of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) between Caucasian and Mexican-American patients. However, there are no ethnic-specific data on alcoholic hepatitis.

Alcoholic hepatitis is the most severe manifestation of ALD and is characterized by an inflammatory process of the liver with neutrophilic infiltration leading to ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, hepatocyte necrosis, steatosis and presence of Mallory bodies. Alcoholic hepatitis clinic presentation is associated with jaundice, fever, hepatomegaly, liver tenderness, encephalopathy, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Ultimately, alcoholic hepatitis is characterized by a high risk of mortality. Latino and Caucasian patients with ALD and alcoholic hepatitis may have different progression and prognosis compared to other ethnicities.

The goal of the present study was to determine the clinical features of alcoholic hepatitis in Latino patients compared to Caucasian patients. The overarching goal is to optimize the care of patients of different ethnicities and identify their challenges when accessing medical care in the United States.

The authors conducted a single-center retrospective chart review of 137 Caucasian patients and 64 Latino patients older than 18 years old diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis. We collected extensive clinical data on their diagnosis, treatment, and outcome.

The major finding was a significantly higher rate of complications of portal hypertension including gastrointestinal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and encephalopathy in Latino compared to Caucasian patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Despite these differences, the two ethnic groups did not present differences in survival. Future studies should prospectively confirm these findings in larger populations.

According to our results, Latinos with alcoholic hepatitis presents with more severe complications of alcoholic hepatitis and appear to have limitations in access to medical treatment of long term complications of portal hypertension. Efforts should be made to ensure improved access to care and compliance.

| 1. | Jaurigue MM, Cappell MS. Therapy for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2143-2158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dufour MC. The critical dimension of ethnicity in liver cirrhosis mortality statistics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1181-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tao N, Sussman S, Nieto J, Tsukamoto H, Yuan JM. Demographic characteristics of hospitalized patients with alcoholic liver disease and pancreatitis in los angeles county. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1798-1804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carrion AF, Ghanta R, Carrasquillo O, Martin P. Chronic liver disease in the Hispanic population of the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:834-841; quiz e109-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mendenhall CL, Gartside PS, Roselle GA, Grossman CJ, Weesner RE, Chedid A. Longevity among ethnic groups in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1989;24:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stewart SH. Racial and ethnic differences in alcohol-associated aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase elevation. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2236-2239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Flores YN, Yee HF Jr, Leng M, Escarce JJ, Bastani R, Salmerón J, Morales LS. Risk factors for chronic liver disease in Blacks, Mexican Americans, and Whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999-2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2231-2238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Roman S, Zepeda-Carrillo EA, Moreno-Luna LE, Panduro A. Alcoholism and liver disease in Mexico: genetic and environmental factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7972-7982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Levy R, Catana AM, Durbin-Johnson B, Halsted CH, Medici V. Ethnic differences in presentation and severity of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:566-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Crabb DW, Bataller R, Chalasani NP, Kamath PS, Lucey M, Mathurin P, McClain C, McCullough A, Mitchell MC, Morgan TR. Standard Definitions and Common Data Elements for Clinical Trials in Patients With Alcoholic Hepatitis: Recommendation From the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:785-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 464] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL Jr, Mezey E, White RI Jr. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:193-199. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1619-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 592] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Jinjuvadia R, Liangpunsakul S; Translational Research and Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment Consortium. Trends in Alcoholic Hepatitis-related Hospitalizations, Financial Burden, and Mortality in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:506-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Hernández MT, Sanchez MA, Ayala L, Magis-Rodríguez C, Ruiz JD, Samuel MC, Aoki BK, Garza AH, Lemp GF. Methamphetamine and cocaine use among Mexican migrants in California: the California-Mexico Epidemiological Surveillance Pilot. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:34-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang AL, Vadhavkar S, Singh G, Omary MB. Epidemiology of alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:649-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, Harrison SA. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1522] [Cited by in RCA: 1636] [Article Influence: 109.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Kallwitz ER, Layden-Almer J, Dhamija M, Berkes J, Guzman G, Lepe R, Cotler SJ, Layden TJ. Ethnicity and body mass index are associated with hepatitis C presentation and progression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Verma S, Bonacini M, Govindarajan S, Kanel G, Lindsay KL, Redeker A. More advanced hepatic fibrosis in hispanics with chronic hepatitis C infection: role of patient demographics, hepatic necroinflammation, and steatosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1817-1823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peters MG, Di Bisceglie AM, Kowdley KV, Flye NL, Luketic VA, Munoz SJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Boyer TD, Lake JR, Bonacini M. Differences between Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2007;46:769-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Serag HB, Lau M, Eschbach K, Davila J, Goodwin J. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hispanics in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1983-1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Field C, Caetano R. The role of ethnic matching between patient and provider on the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions with Hispanics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:262-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | May FP, Rolston VS, Tapper EB, Lakshmanan A, Saab S, Sundaram V. The impact of race and ethnicity on mortality and healthcare utilization in alcoholic hepatitis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2464-2468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kamimura K, Skrypnyk IN, Xu CF S- Editor: Wei LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ