Published online Oct 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i38.6942

Peer-review started: February 8, 2017

First decision: April 21, 2017

Revised: August 29, 2017

Accepted: September 26, 2017

Article in press: September 26, 2017

Published online: October 14, 2017

Processing time: 258 Days and 19 Hours

Dysphagia is a common symptom that is important to recognise and appropriately manage, given that causes include life threatening oesophageal neoplasia, oropharyngeal dysfunction, the risk of aspiration, as well as chronic disabling gastroesophageal reflux (GORD). The predominant causes of dysphagia varies between cohorts depending on the interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental risk factors, and is changing with time. Currently in white Caucasian societies adopting a western lifestyle, obesity is common and thus associated gastroesophageal reflux disease is increasingly diagnosed. Similarly, food allergies are increasing in the west, and eosinophilic oesophagitis is increasingly found as a cause. Other regions where cigarette smoking is still prevalent, or where access to medical care and antisecretory agents such as proton pump inhibitors are less available, benign oesophageal peptic strictures, Barrett’s oesophagus, adeno- as well as squamous cell carcinoma are endemic. The evaluation should consider the severity of symptoms, as well as the pre-test probability of a given condition. In young white Caucasian males who are atopic or describe heartburn, eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease will predominate and a proton pump inhibitor could be commenced prior to further investigation. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy remains a valid first line investigation for patients with suspected oesophageal dysphagia. Barium swallow is particularly useful for oropharyngeal dysphagia, and oesophageal manometry mandatory to diagnose motility disorders.

Core tip: Dysphagia may represent serious and life-threatening pathology such as oesophageal neoplasia or oropharyngeal dysfunction capable of causing aspiration. In young white Caucasian males, eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease are predominant causes, and a trial of proton pump inhibitor is suggested whilst awaiting endoscopy.

- Citation: Philpott H, Garg M, Tomic D, Balasubramanian S, Sweis R. Dysphagia: Thinking outside the box. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(38): 6942-6951

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i38/6942.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i38.6942

Dysphagia is a common symptom in patients presenting to both generalist and specialist medical practitioners[1,2]. The key initial consideration for clinicians is to rule out life-threatening pathology such as neoplasia, and to identify patients who are at risk of aspiration such that immediate intervention can occur[3]. Dysphagia is most commonly due to chronic benign disorders, although it can be associated with appreciable morbidity and impaired quality of life (QOL)[4]. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is the major cause in younger individuals, whilst oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) secondary to cerebrovascular disease is more frequent in the elderly[1,4]. Dysphagia as a symptom attributable to GORD in younger adults does not automatically mandate investigation, rather a trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and strict follow-up to ensure symptomatic resolution might be sufficient[5]. OD and oesophageal dysphagia can often be reliably differentiated symptomatically and might help reduce the risk of aspiration in OD[6]. A comprehensive awareness of the multitude of potential causes of dysphagia, including common medications and rheumatological conditions, is necessary to allow for efficient and thorough evaluation. Judicious investigation with the appropriate choice of tests in order to consider both common and unusual aetiologies is required; high quality endoscopy with care to take sufficient oesophageal biopsies even if mucosa looks normal [e.g., eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE)], high resolution oesophageal manometry (HRM) in suspected motility disturbance, barium swallow and where appropriate, cross-sectional imaging [e.g., computed tomography (CT) scan]. The escalating frequency of GORD and EoE, and the increase in mean age (and associated conditions such as CVA) will ensure that dysphagia remains a common presentation in the future[7,8]. This review attempts to present a contemporary understanding and approach to patients with dysphagia.

Dysphagia is the subjective awareness of an impairment in swallowing of saliva, liquid or solid food. The prevalence varies by age of cohort, method of data collection, and if the dysphagia is classified as acute or chronic[1,4,9]. A community survey of 1000 individuals in Sydney Australia, demonstrated a prevalence of dysphagia of 16% (defined as ever having the symptom), although few (1%) reported dysphagia as chronic or severe[4]. GORD, hypertension and psychological symptoms (anxiety and depression) were independently associated with dysphagia[4]. Subjectivity in symptom reporting and the contribution of GORD have emerged as important themes in contemporary studies of dysphagia[1]. A study of patients with GORD reported resolution of dysphagia with PPI[10]. General practice cohorts have found a frequency of dysphagia of up to 23%, thus reflecting the significant health care burden taken up by this patient group[2]. Self-reported dysphagia is often variably defined[11]; an isolated globus sensation can erroneously be considered a form of dysphagia.

In a large survey of an adult United States population (n = 7640, 3669 respondents), 17% of respondents reported “infrequent” (< 1 episode per week) and 3% “frequent” (> 1 episode per week) dysphagia[1]. On interrogation of these respondents’ medical files, symptoms of heartburn and endoscopic diagnosis of GORD were significantly associated with both the “frequent” and “infrequent” cohorts[1]. Perhaps due to the limited sample size and old age of the respondents (mean 62 years), other typical conditions were not statistically associated with dysphagia. Primary oesophageal conditions (EoE, achalasia, cancer) and systemic conditions (scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis) were only reported amongst the “frequent” dysphagia group[1]. Therefore, clinically significant (or frequent) dysphagia should alert the clinician to serious underlying pathology, whilst infrequent dysphagia is most likely to represent GORD and a trial of acid suppression may be worthwhile in the first instance provided there are no alarm symptoms. This view is supported by several experts in the field (see below).

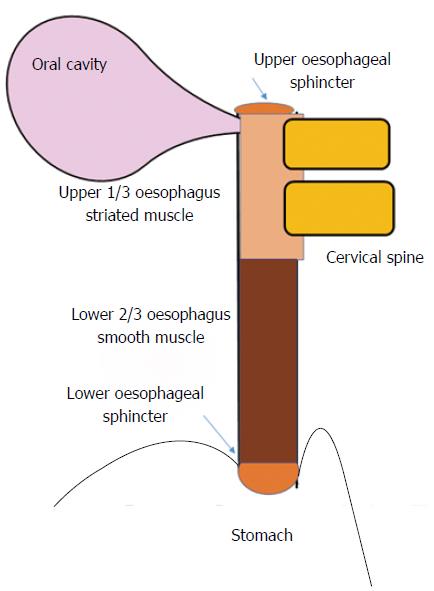

Dysphagia is the subjective awareness of impairment in the passage of food from the oropharynx to the stomach, and therefore may signify an actual delay in bolus transit, or merely the sensation thereof[12]. It is useful to consider the anatomical structures implicated in swallowing (including innervation), and the location of pathology within (Figure 1)[10]. The process of swallowing, whereby food or liquid travels from the mouth to the stomach, involves a complex sequence of muscular contraction and relaxation, involving striated (oropharynx and upper 1/3rd of the oesophagus) and smooth muscle (lower 2/3rd of the oesophagus) that is controlled by motor neurons of the brainstem, and autonomic innervation (of the myenteric plexus) respectively[10,11]. The oropharyngeal component is initially voluntary (including chewing). This is followed by an involuntary phase initiated by food entering the pharynx, whereby the swallowing reflex causes simultaneous relaxation and contraction of the soft palate, upper oesophageal sphincter, oesophagus and lower oesophageal sphincter[6].

Causes of dysphagia vary across the world, and there is evidence of a change in the relative proportion of the various disease states in the last few decades[8]. In the United States, benign oesophageal stricture has become less common, whilst EoE is increasing, along with oesophageal adenocarcinoma[8]. This pattern is mirrored in other Western nations[18]. Oesophageal squamous cell cancer remains a common condition in Asia, whilst Chagas disease still is prevalent is some regions of South America[18].

The oesophageal lumen can become narrowed by inflammation (e.g., erosive reflux disease or EoE), neoplasia or fibrous stricture, or can be compressed externally by lymph nodes or degenerative disease of the cervical spine[8,12-15].

Narrowing of the oesophageal lumen by inflammation, stricture, web or tumour can result in dysphagia[16]. Distal oesophageal inflammation from GORD can result in dysphagia due to transient decrement in peristaltic vigour, and if sustained can lead to fibrous stricture formation[8,15]. Barrett’s oesophagus and/or sliding hiatus hernia (HH) are present in > 80% of those with chronic severe GORD and there is some evidence that both may independently influence oesophageal peristalsis[17,18]. Treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and radiofrequency ablation can lead to fibrosis[19]. The Schatzki ring (a mucosal ring of the distal oesophagus), occurs just proximal to the gastroesophageal sphincter, often within a hiatus hernia, and is relatively common[20,21]. Barium swallow reveals Schatzki ring in 5%-15% of patients with HH[8]. The association with dysphagia and and its cause (congenital, secondary to GERD or even EoE) are debated[22]. Proximal oesophageal webs have been described in individuals with dysphagia. An association with iron deficiency anaemia (the Plummer-Vinson syndrome) was apparently common in the first half of last century, although is rarely reported today[23,24]. EoE is perhaps the most important, benign cause of dysphagia behind GORD. It is increasingly common and may be responsible for some cases previously diagnosed as fibrous strictures or webs[7]. This is an important consideration amongst Caucasian patients in western countries, and is readily treatable (see below)[8,25]. The prevalence of EoE is estimated at between 1 in 500 and 1 in 1000 adult Caucasian males[26]. The importance of EoE is redoubled by the frequent occurrence of food bolus obstruction, a complication that is associated with significant morbidity including the need for hospitalisation, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) and (rarely but catastrophically) oesophageal perforation[27].

Many patients that describe dysphagia will have normal investigations including UGE and high-resolution manometry (HRM), suggesting that a dysfunction of the somatosensory as opposed to neuromuscular apparatus might be present[28,29]. A unifying hypothesis to explain this apparent dichotomy is that a minor disturbance in peristalsis (caused for example by GORD, or non-erosive reflux disease - NERD) may be below the threshold of detection even by sensitive HRM, yet be experienced by the patient as dysphagia. Indeed, many people will describe a resolution of symptoms with proton pump inhibition (PPI). Interventions aimed at modulating the somatosensory system have hence been advocated[28,29].

Achalasia is the prototypical condition classified as a primary (isolated to the oesophagus) disorder of oesophageal motility, yet is quite rare, with an estimated prevalence of 0.17% in individuals undergoing endoscopy[30]. Patients typically present with a chronic history of dysphagia for liquids and/or solids, and often with retrosternal discomfort, heartburn and weight loss[31]. The underlying pathophysiology is of an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons of the myenteric plexus at the distal oesophageal sphincter, with a decrement in inhibitory innervation (nitrous oxide, or vasoactive intestinal peptide) leading to aperistalsis and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter during primary swallowing in classical (Type I) achalasia, pan-oesophageal pressurisation in early (Type II) achalasia or spasm of the oesophageal body (Type III achalasia), but manometry is required to accurately define subtype[32]. Current literature suggests that achalasia is an autoimmune condition associated with antibodies directed at the myenteric plexus and linked to HLA class II DR and DQ alleles[33]. Distal oesophageal spasm and “jackhammer” oesophagus (formerly, nutcracker oesophagus) are disorders of distal oesophageal hypercontractility which can present as dysphagia and/or chest pain and are defined with high resolution manometry as per the recent Chicago classification update (see below)[34-37]. These primary, major disorders of oesophageal motility, may be part of a disease spectrum with shared pathogenesis[38-40]. It is important to always consider secondary achalasia (pseudo-achalasia) that can result from neoplastic infiltration of the distal oesophagus, or be secondary to infection (Chagas disease, primarily occurring in South America)[41,42].

The advent of HRM and subsequent diagnostic algorithms has led to a reconsideration of minor disorders of peristalsis as a cause of dysphagia (defined by the Chicago Classification)[35]. Many patients presenting with dysphagia will have ineffective oesophageal motility in the distal oesophagus or fragmented peristalsis (defined by HRM and the Chicago Classification)[35]. Previously, it had been demonstrated that these abnormalities are frequently found in patients with GORD[43]. The symptom of dysphagia did not correlate with minor disorders or peristalsis on HRM[28,44]. An evolving consensus is arguably emerging that these “abnormalities” may lack clinical application and relevance[44].

To ensure a systematic evaluation occurs and that relevant pathology is not overlooked, an awareness of rheumatological and neurological conditions, medications that may cause oesophageal dysmotility, and causes of extrinsic anatomical compression is required[3,45-48]. Dysphagia is frequently reported by patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) and rheumatoid arthritis, not to mention the more commonly recognised association with systemic sclerosis (as part of the CREST syndrome)[45] (Table 1). More than 1/3 of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome report dysphagia, caused both by xerostomia and thus deficient lubrication of the food bolus, and by abnormal peristalsis demonstrable by oesophageal manometry (particularly in the upper 1/3 of the oesophagus)[45,49]. Similarly, patients with SLE and MCTD frequently describe dysphagia, and proximal oesophageal peristalsis is often weak or fragmented[45]. The cause of the abnormal motility in these conditions is unknown, although an inflammatory myopathy or neuropathy has been postulated[45]. Manometry was unable to correlate these symptoms with dysmotility[45]. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, distal oesophageal peristalsis can be weak or fragmented; although life-threatening subluxation of the cervical spine needs to be considered[50]. Oesophageal dysmotility as a feature of the CREST syndrome is the best known and most studied of the rheumatological conditions, although dysphagia is often overshadowed by heartburn[51,52]. The pathophysiological process of fibrous replacement of the smooth muscle of the mid and lower oesophagus leads to incompetence of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) and the clinical sequalae of GORD and dysphagia[53].

| Medication | Putative mechanism |

| Antipsychotic, e.g., olanzapine[63], clozapine[62] | Block dopamine receptors |

| Tricyclic antidepressant, e.g., amitriptyline[56] | Anticholinergic, decreased saliva and impairment secondary peristalsis |

| Opioids[90] | Increase lower oesophageal contractility, oesophageal spasm |

| Iron supplements | Localised oesophagitis[58,59] |

| Potassium supplements | |

| NSAIDs | |

| Tetracyclines | |

| Macrolides | |

| bisphosphonates | |

| Calcium channel blockers | Smooth muscle relaxation (including lower oesophageal sphincter)[56] |

| Nitrates | |

| Alcohol | |

| Theophylline |

Extrinsic compression of the oesophagus can be a feature of osteoarthritis of the cervical spine, with (particularly) anterior osteophyte formation[13]. This is also occurs in a more florid fashion with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)[54]. Ironically, neurosurgical interventions for degenerative cervical spine disease (such as anterior discectomy) can result in dysphagia both in the short term (with post-operative swelling, or rarely because of damage to the cranial nerves) or long term (compression secondary to a cage implant, if placed)[48]. Other causes of extrinsic compression include mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy (e.g. due to haematological or disseminated solid organ neoplasia) and goitre[14,55].

Medications cause or contribute to dysphagia by influencing oesophageal peristalsis, xerostomia, as a secondary consequence of esophagitis (“pill oesophagitis”), or by causing GORD (Table 2)[47,56-59]. Sedative agents can lead to compromise of airway maintenance and thus aspiration is a risk. Finally, medications that have a local or systemic immunosuppressant effect can predispose to infective oesophagitis[60]. Among individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis, dysphagia may relate, at least in part, to the use of psychotropic medication[61]. The anticholinergic and antidopaminergic effects of antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants have been implicated, not only in causing a dry mouth (anticholinergic) thus limiting lubrication of the food bolus, but also in decreasing the coordination and strength of peristalsis and the timing of lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation[62,63]. It is also possible that serotonergic pathways may be responsible for the dysphagia caused by clozapine, although this hypothesis is perhaps refuted by the absence of case reports relating SSRIs to dysphagia[63]. Individuals with psychiatric diagnoses may also have an increased rate of neurological disorders (such as Parkinson’s disease), particularly among older individuals in residential care, that can cause dysphagia[3,61]. The use of opiates, even if low dose and over the counter, can lead to hypercontractile or hypertensive sequelae of the oesophagus and/or LOS, sometimes even mimicking Type III achalasia.

| Condition | Description |

| Parkinson’s disease[68] | Oropharyngeal and oesophageal dysphagia is possible |

| Multiple sclerosis[64] | Oropharyngeal and oesophageal dysphagia is possible |

| Cerebrovascular disease[3,67] | Oropharyngeal dysphagia typical |

| Motor neuron disease[11,64] | Features of bulbar and pseudobulbar palsy possible |

| Myasthenia gravis[64,91] | |

| Myopathy (various, including inflammatory)[45,64] | Oropharyngeal and proximal oesophageal |

| Cerebellar pathology (various)[64] |

Neurogenic dysphagia, a term loosely applied to cases where the pathology involves the central, autonomic or peripheral nervous system (and not isolated to the oesophagus such as achalasia) is more often characterised by an oropharyngeal component, with neurologists and speech pathologists primarily involved in management[64,65]. Dysphagia is common after cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) involving the cortex often causing hemiplegia[66]. Rapid improvement in swallowing function occurs in the majority[67]. Brainstem infarcts with cranial nerve involvement is another (albeit less common) lesion, but can be severe and sustained[3]. The basal ganglia are the major site of pathology in Parkinson’s disease, and oropharyngeal involvement (with difficulty initiating swallowing and impairment in bolus transit between the pharynx and proximal oesophagus) demonstrable at video fluoroscopy[68]. Awareness of Parkinson’s disease as a cause of dysphagia is of importance to gastroenterologists given the recent finding of neurological pathology beyond the brainstem. Furthermore other gastrointestinal symptoms such as constipation may precede the characteristic clinical syndrome of tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia[68-70]. Other neurogenic causes of dysphagia are outlined in Table 3.

| Condition | Description |

| Scleroderma[52] | Distal oesophageal dysmotility, part of the CREST syndrome |

| Sjogren’s syndrome[49] | Xerostomia limits bolus lubrication and food passage, proximal oesophageal dysmotility |

| Rheumatoid arthritis[45] | Proximal oesophageal dysmotility. Always consider and rule out associated cervical spine disease |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[45] | Proximal oesophageal dysmotility |

| Degenerative cervical spine disease, surgery on the cervical spine and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)[48,54] | Anterior cervical osteophytes cause extrinsic compression of the oropharynx and proximal oesophagus |

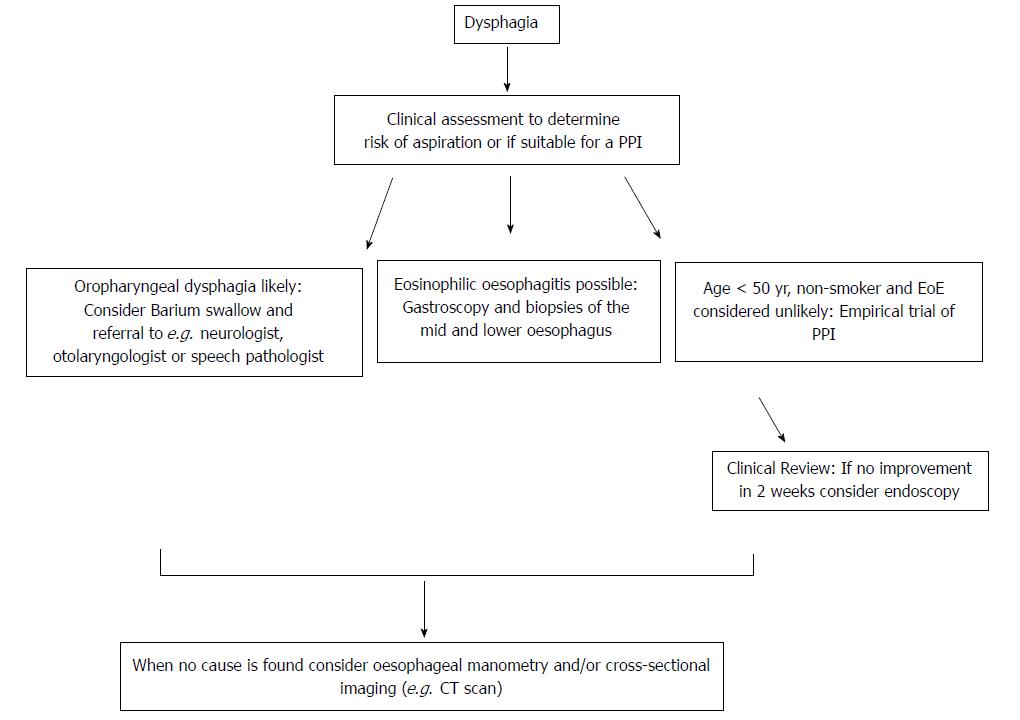

The aetiology of dysphagia can be variably classified, but traditionally oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) and oesophageal dysphagia are defined as distinct groups because the immediate treatment approach to the former is to consider aspiration risk and dietary modification (Figure 2)[6]. It has been estimated that the presence of one or more of a 4-symptom cluster can predict OD accurately: delay in oropharyngeal initiation of swallowing, deglutitive cough, deglutitive nasal aspiration and the need to repetitively swallow to clear nasal secretions[71]. OD is principally managed by neurologists, ENT surgeons and speech pathologists, and is therefore beyond the focus of this review. Further useful sub-classifications of oesophageal disease include dysphagia to solids only (implying an anatomical distortion) or to liquids and solids (implying a physiological or motility disturbance), although the precision of any such clinical “rule of thumb” is not absolute. Longstanding symptoms of mixed dysphagia would normally suggest a motility disturbance[31].

UGE remains a central tool in the investigational algorithm, being essential for the diagnosis of oesophageal malignancy, refractory GORD and EoE[72]. At least middle and lower biopsies of the oesophagus should be taken in patients with dysphagia, even when the macroscopic appearance is normal, primarily with the intention of excluding EoE. The role of UGE as a mandatory primary investigation is debated. Whilst dysphagia can signify life-threatening pathology such as oesophageal or gastric neoplasia, in the majority UGE will be normal or demonstrates only mild erosive disease , leading several experts to advocate a trial of PPI first in otherwise healthy subjects[5]. This is a departure from orthodox teaching where dysphagia is considered an alarm symptom mandating gastroscopy[11]. Thus, a trial of PPI can be considered both diagnostic and therapeutic. The significance of dysphagia however should not be minimised, as the condition is common, and the morbidity in terms of utilisation of healthcare and impairment in quality of life considerable[1,4].

Barium oesophogram (barium swallow) is the next investigation to consider after UGE, particularly when upper oesophageal anatomical or structural pathology is suspected (e.g. a pharyngeal pouch), or to exclude a major motility disorder (e.g. achalasia, spasm) when HRM availability is limited[73,74]. Indeed, experts disagree when it comes to the sequence of the investigations, with some advocating barium swallow as the initial test in all, citing the ability to pre-plan endoscopic inventions such as dilatation, to avoid unnecessary repeated testing and to avoid potential risks including pharyngeal pouch perforation and aspiration in patients with suspected oropharyngeal dysphagia[75]. Barium esophagography can also be considered when extrinsic compression is being considered, or when there is a strong suspicion of para-oesophageal (previously known is “rolling”) HH. Cross-sectional imaging may assist in some cases, with communication between reporting radiologists being imperative in this setting[76,77].

HRM is most useful when a motility disorder is suspected, or if a HH is thought to be contributing to refractory GORD and dysphagia. HRM is more accurate in the diagnosis of sliding HH, and is the gold standard for major disorders of peristalsis (achalasia, distal oesophageal spasm, jackhammer oesophagus and aperistalsis), demonstrating superiority over conventional manometry and barium studies[78-80].

The last decade has seen not only the advent of HRM, but also of intraluminal oesophageal impedance, and intraluminal oesophageal impedance planimetry (commercially known as Endoflip)[81,82]. As well as being a measure of gastric reflux (alkaline and acid), IOI can detect bolus transit abnormalities[83]. Many would argue that whilst this technology has proved of value to researchers, the clinical value is limited or yet unrealised[84]. This assertion is based on data showing that impairment in bolus clearance defined by IOI correlates poorly with both the symptom of dysphagia and with manometric findings[28]. Endoflip has only recently become available and can measure the hitherto unknown parameter of resistance to distension (distensability)[85] .This technology has shown promise in assessing reduced distensiblity in EoE and in post-operative measurement of achalasia response. On the other hand, inclusion of Impedance sensors with HRM has helped provide a visual impression of bolus transport or interruption, which is akin to radiology.

Once a malignant process is excluded, the aims of treatment are to avoid aspiration or food bolus impaction, and minimise the morbidity associated with ongoing symptoms. Effective management of dysphagia obviously starts with early identification of the cause with judicious use of investigations. Requests for endoscopy for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia where the risk of periprocedural aspiration is considerable and the utility questionable should ideally be preceded by an assessment of crico-pharyngeal function and speech pathologist evaluation of oral intake.

Proton pump inhibitors should be used when GORD is suspected as well as in cases of EoE to determine if this might be proton pump Inhibitor responsive oesophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE)[25]. Patients with persistent eosinophilia will require swallowed topical corticosteroids (e.g., budesonide 1 mg orally twice daily administered as an oral viscous solution) or an elimination diet[25]. Specific treatment for oesophageal neoplasia is beyond the scope of this review and will depend on the extent of local invasion or occurrence of metastasis. The treatment of hypercontractile disorders of peristalsis may entail botulinum toxin injection of the distal oesophagus, and of achalasia might include pneumatic dilatation, or myotomy (surgical or per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)][32,38]. Botulinum toxin injection will last only for a few months, and commonly requires repeated therapy[86,87]. Surgical myotomy can result in durable improvement, whilst POEM may offer a less invasive approach, although long-term data is currently unavailable[88,89]. Medications such as oral nitrates or calcium channel blockers lack efficacy but can be used as a holding measure while definitive therapy is being considered[87].

Dysphagia is a common symptom with a diverse range of aetiologies. In young healthy patients that do not describe additional red flag symptoms, a trial of PPI is reasonable and will result in symptomatic resolution in many cases. GORD can cause not only a decrement in peristaltic vigour, but may contribute to hyperalgesia, such that whilst food passes freely into the stomach, the patient experiences dysphagia indicating a somatosensory dysfunction. When further investigation is required, reconsideration of the site and the nature of symptoms (e.g., oropharyngeal vs oesophageal), and early recourse to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is suggested, particularly given the increasing frequency of EoE and thus the need for oesophageal biopsies. HRM is required to exclude major disorders of peristalsis (achalasia, jackhammer oesophagus, distal oesophageal spasm and aperistalsis), although the finding of minor disorders of peristalsis is of unclear significance. Finally, gastroenterologists require a comprehensive knowledge of conditions that may cause or worsen dysphagia so that timely and efficient management occurs.

| 1. | Cho SY, Choung RS, Saito YA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ. Prevalence and risk factors for dysphagia: a USA community study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:212-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Morris H. Dysphagia in a general practice population. Nurs Older People. 2005;17:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Takizawa C, Gemmell E, Kenworthy J, Speyer R. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Stroke, Parkinson's Disease, Alzheimer's Disease, Head Injury, and Pneumonia. Dysphagia. 2016;31:434-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eslick GD, Talley NJ. Dysphagia: epidemiology, risk factors and impact on quality of life--a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:971-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sifrim D, Blondeau K, Mantillla L. Utility of non-endoscopic investigations in the practical management of oesophageal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:369-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ. AGA technical review on management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:455-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Van Rhijn BD, Verheij J, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Rapidly increasing incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in a large cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:47-52.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kidambi T, Toto E, Ho N, Taft T, Hirano I. Temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies from 1999-2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-4341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kuhlemeier KV. Epidemiology and dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1994;9:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vakil NB, Traxler B, Levine D. Dysphagia in patients with erosive esophagitis: prevalence, severity, and response to proton pump inhibitor treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Taft TH, Riehl M, Sodikoff JB, Kahrilas PJ, Keefer L, Doerfler B, Pandolfino JE. Development and validation of the brief esophageal dysphagia questionnaire. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1854-1860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cook IJ. Diagnostic evaluation of dysphagia. Nat Clin Pract. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:393-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Goyal RK, Chaudhury A. Physiology of normal esophageal motility. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:610-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Thien F, Gibson PR, Royce SG. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a clinicopathological review. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;146:12-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Starmer HM, Riley LH 3rd, Hillel AT, Akst LM, Best SR, Gourin CG. Dysphagia, short-term outcomes, and cost of care after anterior cervical disc surgery. Dysphagia. 2014;29:68-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Inayat F, Hussain Q, Shafique K. Dysphagia Caused by Extrinsic Esophageal Compression From Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy in Patients With Sarcoidosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:e119-e120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Oda K, Iwakiri R, Hara M, Watanabe K, Danjo A, Shimoda R, Kikkawa A, Ootani A, Sakata H, Tsunada S. Dysphagia associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease is improved by proton pump inhibitor. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1921-1926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malagelada JR, Bazzoli F, Boeckxstaens G, De Looze D, Fried M, Kahrilas P, Lindberg G, Malfertheiner P, Salis G, Sharma P. World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines: dysphagia--global guidelines and cascades update September 2014. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:370-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Roman S, Kahrilas PJ. The diagnosis and management of hiatus hernia. BMJ. 2014;349:g6154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Savarino E, Gemignani L, Pohl D, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Assandri L, Marabotto E, Bonfanti D, Inferrera S, Fazio V. Oesophageal motility and bolus transit abnormalities increase in parallel with the severity of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:476-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Haidry RJ, Dunn JM, Butt MA, Burnell MG, Gupta A, Green S, Miah H, Smart HL, Bhandari P, Smith LA. Radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic mucosal resection for dysplastic barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma: outcomes of the UK National Halo RFA Registry. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pezzullo JC, Lewicki AM. Schatzki ring, statistically reexamined. Radiology. 2003;228:609-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jamieson J, Hinder RA, DeMeester TR, Litchfield D, Barlow A, Bailey RT Jr. Analysis of thirty-two patients with Schatzki’s ring. Am J Surg. 1989;158:563-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hendrix TR. Schatzki ring, epithelial junction, and hiatal hernia--an unresolved controversy. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:584-585. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Bakari G, Benelbarhdadi I, Bahije L, El Feydi Essaid A. Endoscopic treatment of 135 cases of Plummer-Vinson web: a pilot experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:738-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bakshi SS. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, Thien F, Gibson PR. A prospective open clinical trial of a proton pump inhibitor, elimination diet and/or budesonide for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:985-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, Thien F, Gibson PR. Risk factors for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:1012-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Philpott HL, Nandurkar S, Thien F, Bloom S, Lin E, Goldberg R, Boyapati R, Finch A, Royce SG, Gibson PR. Seasonal recurrence of food bolus obstruction in eosinophilic esophagitis. Intern Med J. 2015;45:939-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xiao Y, Kahrilas PJ, Nicodème F, Lin Z, Roman S, Pandolfino JE. Lack of correlation between HRM metrics and symptoms during the manometric protocol. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:521-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Functional Esophageal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1368–1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Enestvedt BK, Williams JL, Sonnenberg A. Epidemiology and practice patterns of achalasia in a large multi-centre database. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pandolfino JE, Gawron AJ. Achalasia: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:1841-1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Becker J, Haas SL, Mokrowiecka A, Wasielica-Berger J, Ateeb Z, Bister J, Elbe P, Kowalski M, Gawron-Kiszka M, Majewski M. The HLA-DQβ1 insertion is a strong achalasia risk factor and displays a geospatial north-south gradient among Europeans. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1228-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Roman S, Pandolfino JE, Chen J, Boris L, Luger D, Kahrilas PJ. Phenotypes and clinical context of hypercontractility in high-resolution esophageal pressure topography (EPT). Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:37-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Smout AJ, Pandolfino JE; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1373] [Cited by in RCA: 1487] [Article Influence: 135.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gockel I, Lord RV, Bremner CG, Crookes PF, Hamrah P, DeMeester TR. The hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter: a motility disorder with manometric features of outflow obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:692-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kahrilas PJ, Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal motility disorders in terms of pressure topography: the Chicago Classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:627-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249; quiz 1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Huang L, Rezaie A. Progression of Jackhammer Esophagus to Achalasia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:348-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jia Y, McCallum RW. Jackhammer Esophagus Based on the New Chicago Classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hirano T, Miyauchi E, Inoue A, Igusa R, Chiba S, Sakamoto K, Sugiura H, Kikuchi T, Ichinose M. Two cases of pseudo-achalasia with lung cancer: Case report and short literature review. Respir Investig. 2016;54:494-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Freitas EC, Oliveira Mde F, Andrade MC, Vasconcelos AS, Silva Filho JD, Cândido Dda S, Pereira Ldos S, Correia JP, Cruz JN, Cavalcanti LP. PREVALENCE OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN A RURAL AREA IN THE STATE OF CEARA, BRAZIL. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57:431-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bredenoord AJ. Minor Disorders of Esophageal Peristalsis: Highly Prevalent, Minimally Relevant? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1424-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sheehan NJ. Dysphagia and other manifestations of oesophageal involvement in the musculoskeletal diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:746-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Stiefelhagen P. [Dysphagia, constipation, impacted feces: Parkinson disease is also a gastrointestinal disease]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2010;152:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Philpott HL, Nandurkar S, Lubel J, Gibson PR. Drug-induced gastrointestinal disorders. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:411-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Reinard KA, Cook DM, Zakaria HM, Basheer AM, Chang VW, Abdulhak MM. A cohort study of the morbidity of combined anterior-posterior cervical spinal fusions: incidence and predictors of postoperative dysphagia. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:2068-2077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Anselmino M, Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Ostuni P, Ianniello A, Boccú C, Doria A, Todesco S, Ancona E. Esophageal motor function in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: correlation with dysphagia and xerostomia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:113-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Medrano M. Dysphagia in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and iron deficiency anemia. MedGenMed. 2002;4:10. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Tang DM, Pathikonda M, Harrison M, Fisher RS, Friedenberg FK, Parkman HP. Symptoms and esophageal motility based on phenotypic findings of scleroderma. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:197-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Carlson DA, Hinchcliff M, Pandolfino JE. Advances in the evaluation and management of esophageal disease of systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mainie I, Tutuian R, Patel A, Castell DO. Regional esophageal dysfunction in scleroderma and achalasia using multichannel intraluminal impedance and manometry. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | McCafferty RR, Harrison MJ, Tamas LB, Larkins MV. Ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament and Forestier’s disease: an analysis of seven cases. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Bhansali A, Bhadada S, Kochhar R, Muralidharan R, Dash RJ. Multinodular goitre, dysphagia and nodular shadows in the lung. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:627-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Stoschus B, Allescher HD. Drug-induced dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1993;8:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Bashford G, Bradd P. Drug-induced Parkinsonism associated with dysphagia and aspiration: a brief report. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1996;9:133-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Brewer AR, Smyrk TC, Bailey RT Jr, Bonavina L, Eypasch EP, Demeester TR. Drug-induced esophageal injury. Histopathological study in a rabbit model. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1205-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Bonavina L, DeMeester TR, McChesney L, Schwizer W, Albertucci M, Bailey RT. Drug-induced esophageal strictures. Ann Surg. 1987;206:173-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Philpott-Howard JN, Wade JJ, Mufti GJ, Brammer KW, Ehninger G. Randomized comparison of oral fluconazole versus oral polyenes for the prevention of fungal infection in patients at risk of neutropenia. Multicentre Study Group. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:973-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Aldridge KJ, Taylor NF. Dysphagia is a common and serious problem for adults with mental illness: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2012;27:124-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Sagar R, Varghese ST, Balhara YP. Dysphagia due to olanzepine, an antipsychotic medication. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:37-38. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Osman M, Devadas V. Clozapine-induced dysphagia with secondary substantial weight loss. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Bakheit AM. Management of neurogenic dysphagia. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:694-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Malandraki GA, Rajappa A, Kantarcigil C, Wagner E, Ivey C, Youse K. The Intensive Dysphagia Rehabilitation Approach Applied to Patients With Neurogenic Dysphagia: A Case Series Design Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:567-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Cohen DL, Roffe C, Beavan J, Blackett B, Fairfield CA, Hamdy S, Havard D, McFarlane M, McLauglin C, Randall M. Post-stroke dysphagia: A review and design considerations for future trials. Int J Stroke. 2016;11:399-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Perry L, Love CP. Screening for dysphagia and aspiration in acute stroke: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2001;16:7-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Jones CA, Ciucci MR. Multimodal Swallowing Evaluation with High-Resolution Manometry Reveals Subtle Swallowing Changes in Early and Mid-Stage Parkinson Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6:197-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Stokholm MG, Danielsen EH, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Borghammer P. Pathological α-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:940-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Holmqvist S, Chutna O, Bousset L, Aldrin-Kirk P, Li W, Björklund T, Wang ZY, Roybon L, Melki R, Li JY. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:805-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 691] [Article Influence: 57.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 72. | Cook IJ. Investigative techniques in the assessment of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Dig Dis. 1998;16:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679-92; quiz 693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 784] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Cho YK, Choi MG, Oh SN, Baik CN, Park JM, Lee IS, Kim SW, Choi KY, Chung IS. Comparison of bolus transit patterns identified by esophageal impedance to barium esophagram in patients with dysphagia. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Lin Z, Yim B, Gawron A, Imam H, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. The four phases of esophageal bolus transit defined by high-resolution impedance manometry and fluoroscopy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G437-G444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Abdel Jalil AA, Katzka DA, Castell DO. Approach to the patient with dysphagia. Am J Med. 2015;128:1138.e17-1138.e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Kaul BK, DeMeester TR, Oka M, Ball CS, Stein HJ, Kim CB, Cheng SC. The cause of dysphagia in uncomplicated sliding hiatal hernia and its relief by hiatal herniorrhaphy. A roentgenographic, manometric, and clinical study. Ann Surg. 1990;211:406-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Kahrilas PJ, Kim HC, Pandolfino JE. Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:601-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Saleh CM, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. The diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease cannot be made with barium esophagograms. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Weijenborg PW, van Hoeij FB, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Accuracy of hiatal hernia detection with esophageal high-resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Carlson DA, Ravi K, Kahrilas PJ, Gyawali CP, Bredenoord AJ, Castell DO, Spechler SJ, Halland M, Kanuri N, Katzka DA. Diagnosis of Esophageal Motility Disorders: Esophageal Pressure Topography vs. Conventional Line Tracing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:967-77; quiz 978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Bredenoord AJ, Tutuian R, Smout AJ, Castell DO. Technology review: Esophageal impedance monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lin Z, Kahrilas PJ, Xiao Y, Nicodème F, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Pandolfino JE. Functional luminal imaging probe topography: an improved method for characterizing esophageal distensibility in eosinophilic esophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Gao F, Gao Y, Hobson AR, Huang WN, Shang ZM. Normal esophageal high-resolution manometry and impedance values in the supine and sitting positions in the population of Northern China. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Carlson DA, Lin Z, Hirano I, Gonsalves N, Zalewski A, Pandolfino JE. Evaluation of esophageal distensibility in eosinophilic esophagitis: an update and comparison of functional lumen imaging probe analytic methods. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1844-1853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Herbella FA. Critical analysis of esophageal multichannel intraluminal impedance monitoring 20 years later. ISRN. Gastroenterol. 2012;2012:903240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Crespin OM, Liu LWC, Parmar A, Jackson TD, Hamid J, Shlomovitz E, Okrainec A. Safety and efficacy of POEM for treatment of achalasia: a systematic review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2187-2201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | El Khoury R, Teitelbaum EN, Sternbach JM, Soper NJ, Harmath CB, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, Hungness ES. Evaluation of the need for routine esophagram after peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2969-2974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Hungness ES, Teitelbaum EN, Santos BF, Arafat FO, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, Soper NJ. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between peroral esophageal myotomy (POEM) and laparoscopic Heller myotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:228-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Ratuapli SK, Crowell MD, DiBaise JK, Vela MF, Ramirez FC, Burdick GE, Lacy BE, Murray JA. Opioid-Induced Esophageal Dysfunction (OIED) in Patients on Chronic Opioids. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:979-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Cook IJ. Oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:411-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Demirhan E S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A

E- Editor: Ma YJ