Published online Sep 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i36.6741

Peer-review started: May 4, 2017

First decision: June 6, 2017

Revised: July 22, 2017

Accepted: August 25, 2017

Article in press: August 25, 2017

Published online: September 28, 2017

Processing time: 144 Days and 6.5 Hours

Iatrogenic bile duct injuries during cholecystectomy can present as fulminant intra-abdominal sepsis which precludes immediate repair or biliary reconstruction. We report the case of a 29-year-old female patient who sustained a bile duct injury after an open cholecystectomy in a neighboring country. She presented to our institution 22 d after initial surgery with septic shock and multiple intra-abdominal collections. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography revealed a large common hepatic duct defect corresponding to a Strasberg type D bile duct injury. Definitive reconstruction such as a hepaticojejunostomy cannot be performed due to the presence of dense adhesions with infected and friable tissues. She underwent a combination of endoscopic biliary stenting and pedicled omental patch repair of the bile duct to control bile leak and sepsis as a bridging procedure to definite hepaticojejunostomy three months later.

Core tip: Iatrogenic bile duct injury is a challenging condition to treat. This case report describes a novel and innovative surgical technique, whereby a pedicled omental patch repair was performed as a bridging procedure to definitive repair such as a hepaticojejunostomy, in a patient who presented in a delayed fashion with severe intra-abdominal sepsis.

- Citation: Ng JJ, Kow AWC. Pedicled omental patch as a bridging procedure for iatrogenic bile duct injury. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(36): 6741-6746

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i36/6741.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i36.6741

Iatrogenic bile duct injuries (BDIs) are uncommon but can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in patients who had undergone cholecystectomy. Although the incidence of BDIs in LC was reported to be almost tenfold that of OC during the 1990s, LC has now become the gold standard in the treatment of gallstone disease, with a low and declining incidence of BDIs[1,2]. Several studies have reported the rate of BDIs during LC to be between 0.4% to 0.7%, but a more recent retrospective review of more than 10000 patients who had undergone LC showed that the incidence of BDIs was 0.2%, which was comparable to that of OC[3-5]. Approximately one-third of BDIs is diagnosed intra-operatively and are amenable to immediate repair or reconstruction. However, the majority of BDIs are recognized only in the post-operative period with varying clinical presentations such as abdominal pain, jaundice, bile peritonitis or shock[6-8]. BDIs can be classified using the Strasberg classification, with most BDIs manifesting as biliary leaks (Strasberg type A) that can be managed using endoscopic techniques[6]. The other large group of BDIs are common bile duct or common hepatic duct transections (Strasberg type E1 to E3) which usually warrants surgical repair[9]. A tension-free Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is the preferred surgical procedure for reconstitution of bilio-enteric continuity in major common bile duct or common hepatic duct transections, but rarely, in some patients, the presence of severe intra-abdominal sepsis precludes immediate biliary reconstruction[8]. We report a novel method of using a pedicled omental patch, combined with endoscopic biliary stenting, as a bridging procedure to control bile leak, in a patient with severe intra-abdominal sepsis from a large common hepatic duct transection after OC, before attempting definitive hepaticojejunostomy.

A 29-year-old female underwent an open cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis in a hospital from a neighbouring country. Exact intra-operative findings and details of her post-operative recovery were not made available to us. She developed obstructive jaundice on post-operative day three with bilious effluent from her abdominal drain on post-operative day seven. She was initially treated expectantly but due to persistent high bilious output from her abdominal drain, she underwent an exploratory laparotomy on post-operative day 16. The surgeons noted a collapsed common bile duct, but were not able to locate the exact site of bile leak. She was subsequently transferred to our institution on post-operative day 22 for further management for further management of her bile leak.

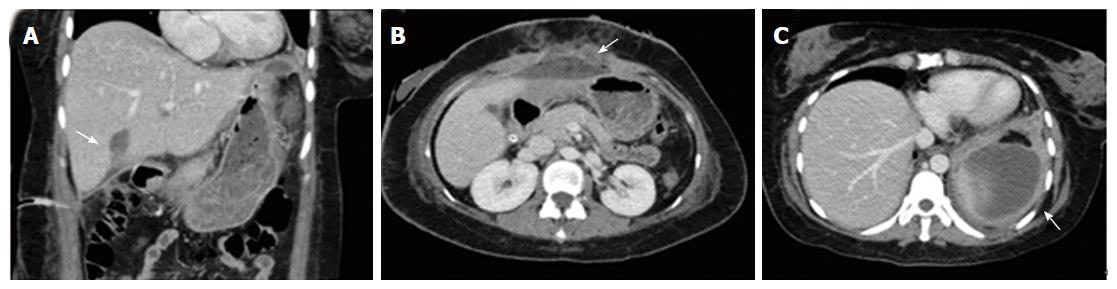

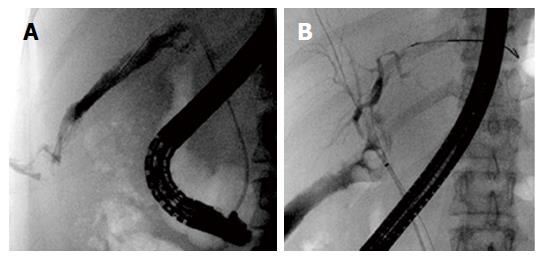

Upon presentation to our institution, the patient was in septic shock. There was active leakage of bilious fluid from her a right subcostal incision. Her abdomen was distended with generalized tenderness. She was resuscitated and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Laboratory investigations revealed elevated infective markers with a white cell count of 19 × 109/L and a C-reactive protein level of 48 mg/L. Serum bilirubin was normal. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a 3 cm biloma at the gallbladder fossa (Figure 1A) with multiple rim-enhancing abdominal collections around the upper abdomen (Figure 1B) - the largest being a 9.3 cm × 8.5 cm perisplenic collection (Figure 1C). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography performed on post-operative day 23 revealed a large common hepatic duct defect just below the bifurcation, corresponding to a Strasberg type D BDI with contrast seen extravasating into the sub-hepatic recess (Figure 2A). After much difficulty, guide-wires were placed across the bile duct defect and plastic biliary stents were deployed into the left and right hepatic ducts respectively (Figure 2B).

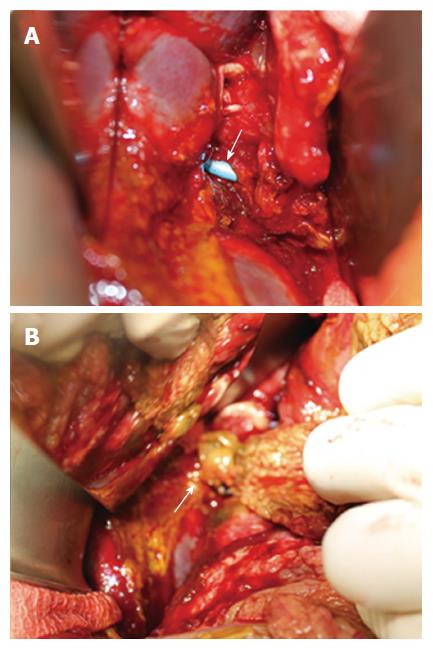

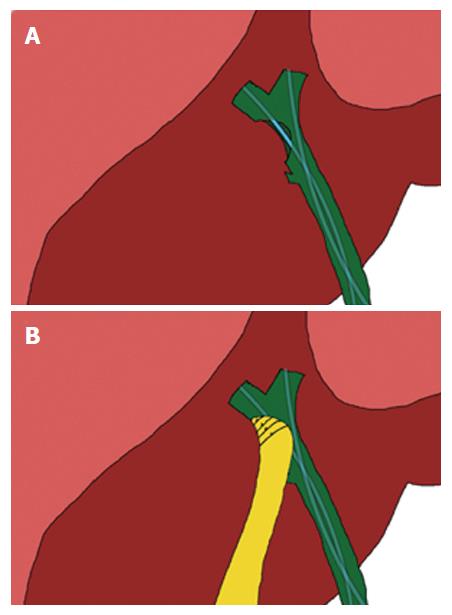

In view of persistent sepsis with the presence of multiple intra-abdominal collections, a decision to perform damage control surgery was taken. At the exploratory laparotomy performed on post-operative day 24, a large 2 cm defect at the anterolateral aspect of the common hepatic duct with biliary stents visible from within was found (Figure 3A). There was a large perisplenic abscess with presence of turbid bile and debris in the sub-hepatic recess which was drained and washed out thoroughly. Neither primary repair of the biliary defect nor biliary reconstruction with a hepaticojejunostomy were suitable options due to dense adhesions around the hepatic hilum with infected and friable surrounding tissues. The biliary drains were unable to completely exclude the biliary system entirely due to the size of the biliary defect. Hence, a well-vascularized and healthy pedicled omental patch was harvested and tagged down circumferentially to the biliary defect using absorbable sutures (Figure 3B). An illustration of the pedicled omental patch is as demonstrated (Figure 4). Drains were placed and the abdomen was closed primarily. The patient improved after surgery with resolution of pyrexia and sepsis. Abdominal drains were removed within eight days of surgery. Laboratory infective markers normalized and serum bilirubin levels remained normal. Intra-abdominal cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae and the patient was sent home to complete four weeks of intravenous antibiotics.

A repeat computed tomography scan of the abdomen three months later revealed complete resolution of the intra-abdominal collections. Although the biliary stents were in-situ, there was mild intrahepatic biliary dilatation suggesting the possibility of a common hepatic duct stricture. The patient subsequently underwent creation of a hepaticojejunostomy one week later. Intra-operatively, there were dense adhesions around the porta hepatis with evidence of early stricture formation at the previous site of BDI. The patient had an uneventful recovery after surgery and was discharged on post-operative day five.

BDIs rarely present in such a delayed fashion with fulminant intra-abdominal sepsis. The initial management of BDIs especially for patients that present late in the post-operative period is directed at delineating the type and extent of BDI, controlling sepsis and ongoing bile leak[8]. We describe a technique that can be utilized as a bridge to definitive bilioenteric reconstruction such as a hepaticojejunostomy when prevailing conditions such as severe intra-abdominal sepsis renders immediate or early reconstruction unfavourable and not ideal. Our technique fulfils the above-mentioned principles of BDI management - first by using endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram to characterize the BDI with placement of biliary stents endoscopically to help control the bile leak. The stents will negate the function of the sphincter of Oddi as well as direct bile into the duodenum. Subsequent laparotomy will allow source control of sepsis via drainage of intra-abdominal abscesses whilst the placement of a pedicled omental patch will ensure proper sealing of the biliary defect and exclusion of the biliary system from the peritoneal cavity. This restores continuity of bile flow, allows for resolution of intra-abdominal sepsis, inflammation and fibrosis, after which definitive bilioenteric reconstruction can be performed at an elective setting as the presence of peritonitis has been reported to confer a poorer outcome in patients undergoing biliary reconstruction[10].

The use of omentum as an autologous graft to seal, patch or reinforce tissues during surgery is widely practiced, and its ability to support and adhere to local tissue is due to its abundant blood supply, angiogenic activity, innate immune function and high concentration of tissue factor[11,12]. Moreover, animal studies have shown that the use of a pedicled omental flap in tissue reconstruction confers an anti-inflammatory effect, which can lead to an improved healing response[13].

Omentum has been commonly used as a patch to close perforations in the gastro-intestinal tract such as a perforated duodenal ulcer. There have been several reports describing the use of omentum in biliary reconstruction. Meissner described his technique of “T-tube stented omentoplasty” used to successfully treat a common hepatic duct stricture. After incising the strictured segment of bile duct resulting in a 4 cm non-circumferential biliary defect, a large bore T-tube was placed within and a pedicled omental flap was then sutured down over the horizontal limb of the T-tube to bridge any remnant biliary defect as well as to envelop the vertical limb. The T-tube was removed after 6 mo with no sequelae and repeat ERC 19 years later showed normal biliary anatomy[14]. Ebata et al[15] also described a similar technique of “hilar cholangioplasty” where he used a pedicled omental flap with a 16F T-tube to seal a 2 cm × 3 cm ductal defect due to a biliobiliary fistula. T-tube cholangioscopy 1 mo after surgery revealed a yellowish polypoid mass at the previous ductal defect and a biopsy taken revealed normal biliary epithelium lining the surface of the grafted omentum. The patient was followed up for 3 years without evidence of cholangitis or abnormal liver function. Another similar technique was described by Chang but he used the falciform ligament instead of the omentum to patch a large bile duct defect due clip necrosis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy[16]. Some authors have also used pedicled omental flaps to reinforce high risk biliary anastomoses in liver transplantation with good results[17].These examples, although limited to individual case reports reaffirms the ideal properties of omentum that make it a suitable autologous graft to aid in biliary reconstruction.

We postulate that our technique could also have been used as a stand-alone procedure without the need of a subsequent hepaticojejunostomy. The biliary stents could then be retrieved endoscopically after 10 to 12 wk. The above-mentioned case reports have shown good long-term patency of the reconstructed bile duct but established data is lacking. A hepaticojejunostomy would still confer the best long-term outcomes, especially in our patient who is young[18]. Using our technique as a stand-alone procedure remains experimental and may be suitable in patients who cannot tolerate longer periods of general anaesthesia needed in a hepaticojejunostomy. Intensive follow-up would be necessary for such patients due to the risk of biliary strictures. We performed a definitive hepaticojejunostomy for our patient as she was due to return to a rural area with no access to regular follow-up for the development of biliary strictures.

Alternative management strategies that could be deployed in our patient would be the placement of percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage tubes or endoscopic biliary stents, combined with either percutaneous or surgically inserted intra-abdominal drains. This might be feasible if the ductal defect was small. However, if the ductal defect is large, the bile leak not be controlled leading to persistent biliary peritonitis and the development of intra-abdominal collections. Moreover, the drains would have to be placed on active suction for a significant period of time to be able to successfully divert and control the bile leak. More often than not, these drains would have to be kept for weeks to months until the patient undergoes definitive bilioenteric reconstruction. In a patient like ours who present with uncontrolled bile leak, intra-abdominal collections and sepsis, the utilization of our technique would allow for control of bile leak without any other additional percutaneous procedures or prolonged drain placement. Another management strategy that could be considered would be use of a T-tube in combination with an omental pedicled flap similar to techniques described above. We were, however, with the assistance of an experienced operator, able to cannulate the left and right hepatic ducts individually and place biliary stents across the biliary defect obviating the need of a T-tube.

Lastly, and most importantly, our case highlights the need for early referral to an institution with experienced hepatobiliary surgeons, endoscopists, or interventional radiologists once a BDI is diagnosed. It is irrefutable evidence that best outcomes are obtained when first repair is performed in experienced tertiary centres[18,19].

This case highlights the need for early referral of BDIs to specialist tertiary centres for further management once detected. Immediate repair or biliary reconstruction is contraindicated in patients with BDIs who present in a delayed fashion with severe intra-abdominal sepsis. We describe an alternative technique which combines endoscopic biliary stenting with a pedicled omental patch as a bridging procedure to definitive hepaticojejunostomy in this group of patients.

A 29-year-old female presented with septic shock and generalized abdominal pain following an open cholecystectomy performed three weeks ago in another hospital.

Physical examination revealed generalized abdominal tenderness and leakage of bile stained fluid from a right subcostal incision.

Bile duct injury, duodenal injury, small bowel injury.

Initial laboratory investigations revealed an elevated total white cell count and C-reactive protein levels.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed multiple large intra-abdominal collections. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography revealed a large common hepatic duct defect (Strasberg type D bile duct injury).

An exploratory laparotomy with a pedicled omental patch repair of the common hepatic duct was performed initially, followed by a definitive hepaticojejunostomy three months later.

This is the first report describing the use of a pedicled omental patch combined with biliary stenting for treatment of a large bile duct injury. Two other case reports have described the use of a pedicled omental patch in conjunction with a T tube for similar bile duct injuries.

In patients who present with severe intra-abdominal sepsis after bile duct injury, up-front creation of a definitive hepaticojejunostomy may not be possible. Instead, a pedicled omental patch repair of the biliary defect may be performed as a bridging procedure to a hepaticojejunostomy, or even as a stand-alone procedure.

The authors presented a novel and alternative technique by using a pedicled omental patch repair as a bridge to a definitive procedure in bile duct injuries.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiu CC, García-Flórez LJ, Tarnawski AS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Dolan JP, Diggs BS, Sheppard BC, Hunter JG. Ten-year trend in the national volume of bile duct injuries requiring operative repair. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:967-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McPartland KJ, Pomposelli JJ. Iatrogenic biliary injuries: classification, identification, and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1329-1343; ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adamsen S, Hansen OH, Funch-Jensen P, Schulze S, Stage JG, Wara P. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective nationwide series. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:571-578. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168-2173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pekolj J, Alvarez FA, Palavecino M, Sánchez Clariá R, Mazza O, de Santibañes E. Intraoperative management and repair of bile duct injuries sustained during 10,123 laparoscopic cholecystectomies in a high-volume referral center. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:894-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101-125. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Sauter PA. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:786-792; discussion 793-795. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lau WY, Lai EC, Lau SH. Management of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a review. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pitt HA, Sherman S, Johnson MS, Hollenbeck AN, Lee J, Daum MR, Lillemoe KD, Lehman GA. Improved outcomes of bile duct injuries in the 21st century. Ann Surg. 2013;258:490-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goykhman Y, Kory I, Small R, Kessler A, Klausner JM, Nakache R, Ben-Haim M. Long-term outcome and risk factors of failure after bile duct injury repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1412-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldsmith HS. The omentum: Research and clinical applications. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990. . |

| 12. | Logmans A, Schoenmakers CH, Haensel SM, Koolhoven I, Trimbos JB, van Lent M, van Ingen HE. High tissue factor concentration in the omentum, a possible cause of its hemostatic properties. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26:82-83. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Uchibori T, Takanari K, Hashizume R, Amoroso NJ, Kamei Y, Wagner WR. Use of a pedicled omental flap to reduce inflammation and vascularize an abdominal wall patch. J Surg Res. 2017;212:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Meissner K. Successful repair of Bismuth type 2 bile duct stricture by T-tube stented omentoplasty: 19 years follow-up. HPB (Oxford). 2001;3:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ebata T, Takagi K, Nagino M. Hilar cholangioplasty using omentum for ductal defect in biliobiliary fistula. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:458-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chang EG. Repair of common bile duct injury with the round and falciform ligament after clip necrosis: case report. JSLS. 2000;4:163-165. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ye QF, Niu Y, She XG, Ming YZ, Cheng K, Ma Y, Ren ZH. Pedicled greater omentum flap for preventing bile leak in liver transplantation patients with poor biliary tract conditions. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:470-473. [PubMed] |