Published online Sep 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6281

Peer-review started: April 17, 2017

First decision: June 7, 2017

Revised: June 9, 2017

Accepted: July 12, 2017

Article in press: July 12, 2017

Published online: September 14, 2017

Processing time: 154 Days and 12.9 Hours

To determine the inter-observer variability for colon polyp morphology and to identify whether education can improve agreement among observers.

For purposes of the tests, we recorded colonoscopy video clips that included scenes visualizing the polyps. A total of 15 endoscopists and 15 nurses participated in the study. Participants watched 60 video clips of the polyp morphology scenes and then estimated polyp morphology (pre-test). After education for 20 min, participants performed a second test in which the order of 60 video clips was changed (post-test). To determine if the effectiveness of education was sustained, four months later, a third, follow-up test was performed with the same participants.

The overall Fleiss’ kappa value of the inter-observer agreement was 0.510 in the pre-test, 0.618 in the post-test, and 0.580 in the follow-up test. The overall diagnostic accuracy of the estimation for polyp morphology in the pre-, post-, and follow-up tests was 0.662, 0.797, and 0.761, respectively. After education, the inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy of all participants improved. However, after four months, the inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy of expert groups were markedly decreased, and those of beginner and nurse groups remained similar to pre-test levels.

The education program used in this study can improve inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy in assessing the morphology of colon polyps; it is especially effective when first learning endoscopy.

Core tip: Paris classification is used worldwide in clinical practice to categorize the morphology of gastrointestinal polyps. However, few studies regarding the inter-observer variability associated with this classification have been reported. In this study, we identified that an education program could be helpful in improving inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy when determining the morphology of colon polyps, and that the educational program was especially effective when first learning endoscopy. We suggest that daily practice of morphology assessment of colon polyps and the proper education of the Paris classification are essential in maintaining the quality of colonoscopic examination.

- Citation: Kim JH, Nam KS, Kwon HJ, Choi YJ, Jung K, Kim SE, Moon W, Park MI, Park SJ. Assessment of colon polyp morphology: Is education effective? World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(34): 6281-6286

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i34/6281.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6281

Adenomatous polyps are the most common neoplasm detected during colonoscopic examination, and patients with this type of polyp have a greater risk of developing advanced neoplasia[1-5]. According to the National Polyp Study[6,7], colonoscopy is a useful tool in detecting colorectal polyps, and colonoscopic removal of adenomatous polyps prevents death from colorectal cancer (CRC). The size, location, and grade of polyp dysplasia are correlated with potential risks of malignant evolution[8-10], and the endoscopic appearance of polyps can predict invasion into the submucosa[11-13]. The invasive growth rates of depressed lesions, sessile lesions, and pedunculated lesions are 61%, 34% and 5%, respectively[14,15]. Therefore, polyp morphology is an important factor in determining the therapeutic method of endoscopic treatment or surgery.

When a colon polyp is confined to the mucosa or upper part of the submucosa, it can be safely removed by endoscopic procedure. However, insufficient recognition of lesions, particularly flat lesions including sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSA/P), can result in incomplete endoscopic resection, which is strongly associated with interval cancer[16,17]. In 2002, Western and Japanese endoscopists, surgeons, and pathologists gathered and presented the Paris classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract[14]. The Paris classification is now utilized worldwide to classify the morphology of polyps in clinical practice. However, few studies regarding inter-observer variability associated with this classification have been reported. Recently, Van Doorn et al[18] assessed the inter-observer agreement for the Paris classification among seven Western expert endoscopists and found that agreement was moderate and did not change after training. They suggested that the usefulness and the educational impact of this classification in clinical practice are questionable, and that the introduction of a simplified classification system is needed. However, additional studies that include Eastern expert endoscopists are necessary in order to generalize these results.

In the current study, we aimed to evaluate inter-observer variability for colon polyp morphology and to determine the effectiveness and persistence of an education program for both Korean experts and beginners.

For purposes of this study, colon polyps detected by colonoscopy were recorded as photographic images. Two experienced gastroenterologists (Kwon HJ and Choi YJ) performed colonoscopic examinations and recorded several pictures of polyps at various alignments. From these, a study investigator (Nam KS) selected five to seven for each polyp and created a video clip by connecting the pictures using Windows Movie Maker (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, United States). A total of 80 video clips were created and edited to 10-15 s in length. Sixty video clips were used for the exam and 20 video clips for the learning sets. To minimize any bias in assessing polyp morphology, all video clips were reviewed by two experienced gastroenterologists (Jung K and Kim SE).

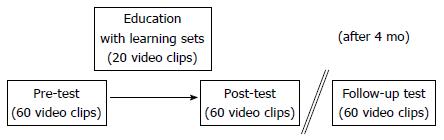

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kosin University Gospel Hospital. All study participants were provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment. Fifteen endoscopists and 15 nurses participated in the study. Nine of the endoscopists were experienced (expert group) and had performed more than 1000 colonoscopies, six were endoscopic training fellows (beginner group) who had performed fewer than 300 colonoscopies, and 15 were nurses working in endoscopic practice (nurse group). The study included a pre-test, an educational program, a post-test, and a follow-up test, as shown in Figure 1.

On the day of the exam, participants received an explanation about the aim of the study and were asked to assess 60 polyps according to the Paris classification. They watched 60 video clips and recorded (in writing) the polyp morphology (Ip, Isp, Is, IIa, IIb, IIc, or III) (“pre-test”). After the first exam, a study investigator presented a 20-min educational program that included a detailed explanation of the Paris classification and 20 learning video clips that consisted of standard pictures illustrating the Paris classification (“education”). Following this, participants completed the second exam, in which the order of 60 video clips (“post-test”) was changed. Four months later, we randomly administered the third exam (“follow-up” test) to the same participants to determine if the effectiveness of education was sustained. When analyzing exam results, we assessed inter-observer agreement and the diagnostic accuracy of each exam and compared the results.

Inter-observer agreement was evaluated by calculating the Fleiss’ kappa value between participants. We assessed inter-observer agreement for all participants and compared expert, beginner, and nurse groups. Kappa values below 0.40 and of 0.41-0.60, 0.61-0.80, and greater than 0.80 were defined as fair agreement, moderate agreement, substantial agreement, and almost perfect agreement, respectively. We also evaluated the assessed category of polyp morphology for each polyp. For example, if the participants all chose Ip for a polyp, it was assessed as one category per one question. If the participants chose Is or IIa for a polyp, it was assessed as two categories per one question. We also estimated and compared the diagnostic accuracy of the three groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM®, Armonk, NY, United States).

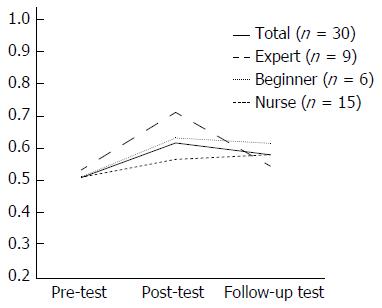

The colon polyp characteristics used in the exam are summarized in Table 1. Figure 2 illustrates the inter-observer agreement of the estimated polyp morphology. The overall Fleiss’ kappa value of the inter-observer agreement was 0.510 in the pre-test, 0.618 in the post-test, and 0.580 in the follow-up test. In the expert group, the inter-observer agreement improved after education (0.533 in pre-test → 0.713 in post-test); however, after four months, the agreement decreased to a level similar to that of the pre-test (0.544 in the follow-up test). In the beginner group, the inter-observer agreement improved after education (0.514 in pre-test → 0.631 in post-test); after four months, the agreement slightly decreased to a value similar to that at the post-test (0.616 in the follow-up test). In the nurse group, the inter-observer agreement improved after education (0.508 in pre-test → 0.566 in post-test); after four months, the agreement was slightly improved to a value similar to that at the post-test (0.576 in follow-up test).

| Number | |

| Size | |

| ≤ 5 mm | 14 (23.3) |

| 5 < and ≤ 10 mm | 32 (53.4) |

| ≥ 10 mm | 14 (23.3) |

| Type | |

| Ip | 14 (23.3) |

| Isp | 9 (15.0) |

| Is | 19 (31.7) |

| IIa | 16 (26.6) |

| IIb | 0 (0.0) |

| IIc | 1 (1.7) |

| III | 1 (1.7) |

| Location | |

| Rectum | 5 (8.3) |

| Sigmoid colon | 24 (40.0) |

| Descending colon | 5 (8.3) |

| Transverse colon | 13 (21.7) |

| Ascending colon | 11 (18.4) |

| Cecum | 2 (3.3) |

| Histology | |

| TA with LGD | 32 (53.3) |

| TA with HGD | 3 (5.0) |

| VTA with LGD | 2 (3.3) |

| VTA with HGD | 1 (1.7) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 4 (6.7) |

| Chronic colitis | 13 (21.7) |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 3 (5.0) |

| Inflammatory polyp | 2 (3.3) |

In Table 2, the difference in assessment of polyp morphology was shown for each test. The proportion of one category per one question was 25.0% in the pre-test, 46.7% in the post-test, and 35.0% in the follow-up test. The proportion of two categories per one question was 63.3% in the pre-test, 48.3% in the post-test, and 58.3% in the follow-up test. The proportion of three categories per one question was similar in each test.

| Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up test | |

| Number of polyps | |||

| One category per one question | |||

| Ip | 9 (15.0) | 8 (13.3) | 12 (20.0) |

| Isp | 6 (10.0) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Is | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.0) | 3 (5.0) |

| IIa | 0 (0.0) | 11 (18.3) | 6 (10.0) |

| Total | 15 (25.0) | 28 (46.7) | 21 (35.0) |

| Two categories per one question | |||

| Ip-Isp | 6 (10.0) | 8 (13.3) | 5 (8.3) |

| Isp-Is | 7 (11.7) | 7 (11.7) | 8 (13.3) |

| Is-IIa | 24 (40.0) | 12 (20.0) | 20 (33.3) |

| IIa-IIc | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) |

| IIc-III | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) |

| Total | 38 (63.3) | 29 (48.3) | 35 (58.3) |

| Three categories per one question | |||

| Ip-Isp-Is | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 4 (6.7) |

| Isp-Is-IIa | 5 (8.3) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Is-IIa-IIc | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| IIa-IIb-IIc | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 7 (11.7) | 3 (5.0) | 4 (6.7) |

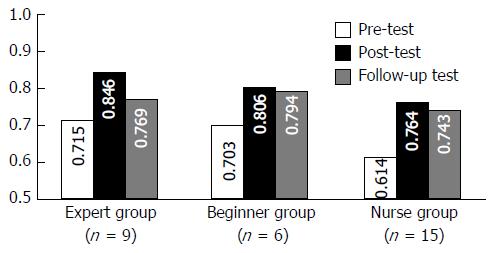

The overall diagnostic accuracy of the estimation for polyp morphology in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up tests was 0.662, 0.797, and 0.761, respectively (data not shown). Figure 3 shows the diagnostic accuracy of the estimation for polyp morphology of each group. In the expert group, the diagnostic accuracy was improved after education (0.715 in pre-test → 0.846 in post-test); however, after four months, the diagnostic accuracy decreased (0.769 in the follow-up test). In the beginner and nurse groups, diagnostic accuracy improved after education (beginner group, 0.703 in pre-test → 0.806 in post-test; nurse group, 0.614 in pre-test → 0.764 in post-test); after four months, the diagnostic accuracy was similar to the value at the post-test (beginner group, 0.794 in follow-up test; nurse group, 0.743 in follow-up test).

In this study, 15 endoscopists and 15 nurses participated in a total of three exams to evaluate the validity of the Paris classification in assessing colon polyp morphology. When analyzing exam results, we found that the education improved inter-observer agreement and the diagnostic accuracy of estimated polyp morphology. In addition, the effectiveness of education was sustained over time in the beginner and nurse groups, especially.

The Paris classification is a system that classifies the endoscopic appearance of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract and distinguishes polypoid and non-polypoid lesions[14]. Polypoid lesions are divided into pedunculated (Ip) or sessile (Is) types, and non-polypoid lesions are divided into superficial slightly elevated (IIa), flat (IIb), superficial depressed (IIc), and excavated (III) types[14]. The awareness of non-polypoid lesions and technical advances including chromoendoscopy, high-resolution endoscopy, and magnifying endoscopy have contributed to a higher detection rate of early colorectal carcinoma[19,20]. The detection rate of adenoma has been shown to be closely associated with the risk of interval CRC[21]. In a systematic review, the miss rate for adenomatous polyps was 13% for sizes of 5-10 mm and 26% for sizes of 1-5 mm, and the miss rate for non-adenomatous polyps was 22% with a size < 10 mm[22]. Also importantly, it holds true that we can see only what we already know[23]. Before the endoscopic findings of SSA/P were reported, the detection of SSA/P was rare, and even detected SSA/Ps were considered to be hyperplastic polyps[16,24]. Therefore, proper awareness of the Paris classification in assessing colon polyp morphology could be helpful in increasing polyp detection rates.

We assessed inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy for colon polyp morphology in three exams, pre-, post-, and follow-up tests. After education for 20 min, inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy improved. These results demonstrated that a short, didactic education program was effective in correcting individuals’ misunderstandings when assessing the morphology of colon polyps according to the Paris classification. However, after four months, the inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy of expert groups were markedly decreased, whereas those of beginner and nurse groups were similar to the level of the post-test. Van Doorn et al[18] identified that the inter-observer agreement of seven Western experts was moderate and unchanged at three months post-training. In our study, test results for nine experts were similar to those of the Western experts; however, the test results of beginner and nurse groups were different from those of the experts. These results indicate that the effectiveness of education for polyp morphology is lasting for beginner and nurse groups, but not for the expert group. Members of the expert group had performed more than 1000 colonoscopies over an extended time and assessed the morphology of colon polyps according to their own understanding of the Paris classification. This might explain why the educational effect in this group did not last more than a few months. The beginner and nurse groups had little to no experience with colonoscopic examination and had utilized the Paris classification for a short time. For this reason, the education for polyp morphology in the beginner and nurse groups could more easily alter their existing knowledge, and the educational effect could last for several months. These findings suggest that appropriate education at the onset of learning endoscopy is effective in improving inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy when assessing the morphology of colon polyps.

This study has some limitations. First, it was performed in a single medical center in Korea. Although we included a total of 30 participants, our results might not represent the practice of Eastern endoscopists as a whole. However, because data are limited regarding Eastern endoscopists’ assessments of colon polyp morphology according to the Paris classification, our results could be helpful in assessing the validity and usefulness of the Paris classification in clinical practice. Second, we did not evaluate inter-observer agreement or diagnostic accuracy according to polyp size. Polyps used in the exam were collected in various sizes (Table 1), in order to minimize selection bias. Third, our study included a small number of type IIb, type IIc, and type III polyps (3.4%). According to the results of Kudo et al[25] who classified the morphology of 9533 colon polyps, 57% were type I s, 39% were type IIa or IIb, 4% were type IIc, and 0% were type III. Therefore, it is difficult to fully assess the inter-observer variability for type IIb, type IIc, and type III polyps due to their rarity.

In conclusion, this study is the first to evaluate the validity of the Paris classification system in Eastern countries for evaluating the morphology of colon polyps. Our results indicate that an education program could be helpful in improving inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy when determining colon polyp morphology, and such an educational program is expected to be especially effective upon first learning endoscopy. Based on these study results, we suggest that daily practice of morphology assessment of colon polyps and proper education in the Paris classification are essential in maintaining the quality of colonoscopic examination.

The Paris classification is an international classification system for describing gastrointestinal tract polyp morphology based on endoscopic appearances. However, there is little data regarding inter-observer variability and the impact of education about this classification on clinical practice. In this study, they aimed to determine the inter-observer variability for colon polyp morphology and to identify whether education can improve agreement among observers.

This study presents that the education program used in this study can improve inter-observer agreement and diagnostic accuracy in assessing the morphology of colon polyps; it is especially effective when first learning endoscopy.

In this study, a total of 30 Korean endoscopists and nurses participated. This study included a pre-test, an educational program, a post-test, and a follow-up test. The authors assessed inter-observer agreement for all participants and compared expert, beginner, and nurse groups. The authors also estimated and compared the diagnostic accuracy of the three groups.

Daily practice of morphology assessment of colon polyps and the proper education of the Paris classification are essential in maintaining the quality of colonoscopic examination.

Pre-test: a test without any education. Post-test: a test after a 20-min educational program. Follow-up test: a test after four months without an educational program

Based on these study results,a proper education in the Paris classification are important to maintaining the quality of colonoscopicexamination, especially in new learner in endoscopy.

| 1. | Cottet V, Jooste V, Fournel I, Bouvier AM, Faivre J, Bonithon-Kopp C. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after adenoma removal: a population-based cohort study. Gut. 2012;61:1180-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loeve F, van Ballegooijen M, Boer R, Kuipers EJ, Habbema JD. Colorectal cancer risk in adenoma patients: a nation-wide study. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:147-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975;36:2251-2270. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Robertson DJ, Greenberg ER, Beach M, Sandler RS, Ahnen D, Haile RW, Burke CA, Snover DC, Bresalier RS, McKeown-Eyssen G. Colorectal cancer in patients under close colonoscopic surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:34-41. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, Watabe H, Okamoto M, Kawabe T, Wada R, Doi H, Omata M. Incidence and recurrence rates of colorectal adenomas estimated by annually repeated colonoscopies on asymptomatic Japanese. Gut. 2004;53:568-572. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3107] [Cited by in RCA: 3182] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2397] [Article Influence: 171.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Fung CH, Goldman H. The incidence and significance of villous change in adenomatous polyps. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;53:21-25. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lotfi AM, Spencer RJ, Ilstrup DM, Melton LJ 3rd. Colorectal polyps and the risk of subsequent carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:337-343. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Shinya H, Wolff WI. Morphology, anatomic distribution and cancer potential of colonic polyps. Ann Surg. 1979;190:679-683. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Boenicke L, Fein M, Sailer M, Isbert C, Germer CT, Thalheimer A. The concurrence of histologically positive resection margins and sessile morphology is an important risk factor for lymph node metastasis after complete endoscopic removal of malignant colorectal polyps. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haggitt RC, Glotzbach RE, Soffer EE, Wruble LD. Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in adenomas: implications for lesions removed by endoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:328-336. [PubMed] |

| 13. | van Heijningen EM, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuipers EJ, Dekker E, Lesterhuis W, Ter Borg F, Vecht J, De Jonge V, Spoelstra P, Engels L. Features of adenoma and colonoscopy associated with recurrent colorectal neoplasia based on a large community-based study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1410-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T, Rouse RV, Park W, Maheshwari A, Sato T, Matsui S, Friedland S. Prevalence of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic and symptomatic adults. JAMA. 2008;299:1027-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pohl H, Srivastava A, Bensen SP, Anderson P, Rothstein RI, Gordon SR, Levy LC, Toor A, Mackenzie TA, Rosch T. Incomplete polyp resection during colonoscopy-results of the complete adenoma resection (CARE) study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:74-80.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Doorn SC, Hazewinkel Y, East JE, van Leerdam ME, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Sanduleanu-Dascalescu S, Bastiaansen BA, Fockens P, Dekker E. Polyp morphology: an interobserver evaluation for the Paris classification among international experts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Galloro G, Ruggiero S, Russo T, Saunders B. Recent advances to improve the endoscopic detection and differentiation of early colorectal neoplasia. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17 Suppl 1:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bruno MJ. Magnification endoscopy, high resolution endoscopy, and chromoscopy; towards a better optical diagnosis. Gut. 2003;52 Suppl 4:iv7-iv11. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1674] [Article Influence: 139.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 878] [Cited by in RCA: 933] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sonnenberg A. We see only what we already know [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:AB353. |

| 24. | Yamada A, Notohara K, Aoyama I, Miyoshi M, Miyamoto S, Fujii S, Yamamoto H. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenoma and other serrated colorectal polyps. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:45-51. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kudo S, Kashida H, Tamura S, Nakajima T. The problem of “flat” colonic adenoma. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:87-98. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Lakatos PL, Zhang QS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF