Published online Sep 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6172

Peer-review started: February 8, 2017

First decision: February 23, 2017

Revised: March 28, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: September 7, 2017

Processing time: 215 Days and 17.5 Hours

To determine the level of consensus on the definition of colorectal anastomotic leakage (CAL) among Dutch and Chinese colorectal surgeons.

Dutch and Chinese colorectal surgeons were asked to partake in an online questionnaire. Consensus in the online questionnaire was defined as > 80% agreement between respondents on various statements regarding a general definition of CAL, and regarding clinical and radiological diagnosis of the complication.

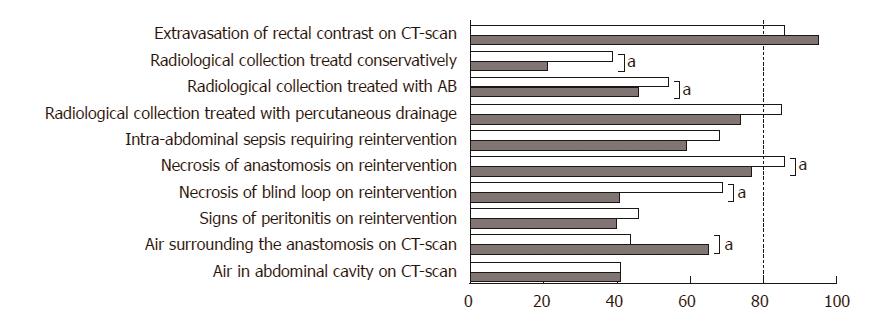

Fifty-nine Dutch and 202 Chinese dedicated colorectal surgeons participated in the online survey. Consensus was found on only one of the proposed elements of a general definition of CAL in both countries: ‘extravasation of contrast medium after rectal enema on a CT scan’. Another two were found relevant according to Dutch surgeons: ‘necrosis of the anastomosis found during reoperation’, and ‘a radiological collection treated with percutaneous drainage’. No consensus was found for all other proposed elements that may be included in a general definition.

There is no universally accepted definition of CAL in the Netherlands and China. Diagnosis of CAL based on clinical manifestations remains a point of discussion in both countries. Dutch surgeons are more likely to report ‘subclinical’ leaks as CAL, which partly explains the higher reported Dutch CAL rates.

Core tip: The present international online survey proves the inconsistent views as to what is considered colorectal anastomotic leakage among surgeons in the Netherlands and China, and shows large differences between the countries. This is in line with the current literature, since there is no uniformly accepted definition worldwide. We therefore propose to perform a systematic literature review to identify the available definitions. The final stage would be to perform a Delphi analysis within a representative panel of colorectal surgeons to develop a widely accepted definition of colorectal anastomotic leakage.

- Citation: van Rooijen SJ, Jongen AC, Wu ZQ, Ji JF, Slooter GD, Roumen RM, Bouvy ND. Definition of colorectal anastomotic leakage: A consensus survey among Dutch and Chinese colorectal surgeons. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(33): 6172-6180

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i33/6172.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6172

Colorectal anastomotic leakage (CAL) remains gastrointestinal surgeons’ most feared complication, despite important improvements in perioperative care and the development of novel surgical techniques. It is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality[1,2], poor quality of life[3], and increased healthcare costs[4,5]. Since CAL influences the direct postoperative course and has recently been proven to impact oncological outcome as well[6-8], it is frequently used as an outcome measure in clinical studies. However, the CAL rates vary considerably in the international literature from 1.5% to 23%[9,10]. Large variations in leakage rates have been reported between studies published by Western and Asian research groups, in which the reported incidence of CAL in Asian publications is substantially lower[5,11-14]. Such differences can be partly explained by the variations of operation technique, tumor location, and patient characteristics[15,16]. However, little attention has been paid to potential differences in the CAL definition and the available methods of diagnosis.

Although CAL is sometimes defined as “a defect in the bowel wall at the anastomotic site, leading to communication of intra- and extraluminal compartments”[17], this definition translates rather difficult to the clinical situation. Therefore, many authors formulate new definitions or diagnostic criteria in their studies, which usually include clinical and radiological features[18], and the impact of a leak on the treatment plan. However, since the pathophysiology of anastomotic leakage is multifactorial, the manifestation of a clinical leak can be rather variable[15]. Furthermore, due to the increased use of (routine) diagnostics such as CT or contrast enema, ”radiological” leaks that do not eventually influence patient management are diagnosed more often. These factors complicate comparison of study results, and weaken the reliability of further analyses. This in turn hampers the construction of evidence-based guidelines on patient management and surgical technique.

Clearly, there is a need for a generally accepted and practical definition for CAL and its diagnostic criteria to serve as a template for future research on CAL and the clinical decision-making process[19]. Several surveys have been performed to reach consensus regarding the definition of CAL, however, most of them were restricted to a single country[19]. We hypothesized that the aforementioned reported differences in incidence rates between Asian and Western countries can partly be explained by differences in the definitions and diagnostic methods used. The aim of this study was therefore to determine the level of consensus regarding different aspects of a general definition of CAL within and between populations of Chinese and Dutch colorectal surgeons, that can be considered good representatives of the East and West, respectively.

An online survey was performed among colorectal surgeons from the Netherlands and China. In the Netherlands, the survey was constructed and run through an online database using SurveyMonkey TM (Palo Alto, CA, United States). Colorectal surgeons in the Netherlands were identified from the contacts section of the colorectal subdivision of the Dutch Society of Gastro Intestinal Surgery (NVGIC): the Taskforce Coloproctology (WCP). Within this subdivision, 141 senior and junior colorectal surgeons were identified. Respondents were invited to partake in the online survey by email. Dutch surgeons completed the questionnaire between May and June 2015.

In China, the survey was conducted on the platform provided by DXY (http://www.dxy.cn), which is the largest medical website in China with more than one million registered medical users. An invitation was sent to all the registered colorectal surgeons to invite them to participate in a five-minute survey. Due to a relatively large number of registered users, the survey was designed to be terminated when 200 replies were received. Surgeons from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan were not invited in this survey, because of the application of different medical systems in those areas. A demographic chart of the regions represented by the respondents can be observed in Figure 1.

The survey was divided into three major categories with questions addressing the general definition, and the clinical and radiological diagnosis of CAL. It was partly adapted from a previous study of Adams et al[20] and was initially constructed in English, and then translated to Dutch and Chinese by surgeons fluent in both English and Dutch and English and Chinese for the Dutch and Chinese versions, respectively, and checked for interpretation bias. Details of the English questionnaire are shown in Table 1 (See supplementary data for Dutch and Chinese versions).

| General definition | ||||

| Do we have to consider the following findings as anastomotic leakage? | Yes | No | ||

| 1 | Extravasation of contrast after rectal enema on a CT scan | |||

| 2 | Radiological collection around the anastomosis and no treatment | |||

| 3 | Radiological collection around the anastomosis treated with antibiotics | |||

| 4 | Radiological collection around the anastomosis treated with percutaneous drainage | |||

| 5 | Abdominal sepsis and reoperation needed | |||

| 6 | Necrosis of the anastomosis seen at reoperation | |||

| 7 | Necrosis of the blind loop seen at reoperation | |||

| 8 | Signs of peritonitis during reoperation | |||

| 9 | Air bubbles around the anastomosis seen on a CT scan | |||

| 10 | Free intra-abdominal air seen on a CT scan | |||

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||

| In what extent do the following clinical parameters contribute to the suspicion of colorectal anastomotic leakage? Please note the relevance on a numeric scale of 0-10: | ||||

| 1 | Increased C-reactive protein | |||

| 2 | Increased leukocytes | |||

| 3 | Tachycardia | |||

| 4 | Increased respiratory rate | |||

| 5 | (Sub-) febrile temperature | |||

| 6 | Postoperative ileus (> 4 d) | |||

| 7 | Deterioration in clinical condition | |||

| 8 | Abdominal pain, other than wound pain | |||

| Radiological diagnosis | ||||

| Answer the following questions using percentages (0% = never, 100% = always) | ||||

| 1 | In how many percent of patients with clinical suspicion of anastomotic leakage do you perform radiodiagnostics? | |||

| 2 | In how many percent of patients with clinical suspicion of anastomotic leakage do radiodiagnostics change your treatment policy? | |||

| 3 | In how many cases did the CT scan report no anastomotic leakage while there finally was an anastomotic leakage. | |||

| 4 | In how many percent of cases do you consider a reoperation without previous radiodiagnostics? | |||

| Early anastomotic leakage | ||||

| In your opinion, is ‘very early (< 3 d) anastomotic leakage the result of technical failure? | ||||

| 1 | Yes | |||

| 2 | No | |||

Category I mainly focused on the agreement of general definitions used in the international literature[20]. Surgeons were asked to state whether ten different clinical situations should or should not be included in a general definition. Category II focused on clinical manifestations and their predictive value for CAL. A 10-point grading scale ranging from 1 (not predictive at all) to 10 (very predictive) was used to assess the agreement of the respondents’ views on the clinical parameters. The parameters used were partially adapted from the Dutch Leakage Score (DULK)[11]. Category III consisted of four questions regarding the use of radiological examination and the influence of this diagnostic method on patient care. This third category was also partially adapted from Adams et al[20]. The last general question focused on surgeons’ views regarding the cause of very early anastomotic leakage.

Very early anastomotic leakage was defined as leakage occurring within the first three days post-surgery.

Postoperative ileus was defined as an interval of more than 4 d from surgery until passage of flatus or stool and the tolerance of an oral diet[21].

Blind loop was defined as a bypassed loop of bowel after the construction of an end-to-end or end-to-side bowel anastomosis.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to summarize data for the online survey. Consensus was defined as > 80% agreement between respondents on various statements, as described by Duncan et al[22]. If less than 80% of respondents deemed the statements important, it was stated that no consensus was reached. Graphical depictions of information were used where appropriate to facilitate data interpretation. Chi square test or Mann-Whitney test were applied with proper indications. A P-value smaller than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Of the 141 colorectal Dutch surgeons who were invited to partake in the online survey, 62 respondents accepted the invitation, and 59 completed the survey, resulting in a 42% response rate and 95% survey completion. In total, 100% of 201 questionnaires received from Chinese surgeons were completed. A demographic chart of the regions represented by the respondents can be observed in Figure 1, as it shows that this survey covers 96.8% (30/31, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan not included) of provinces and areas of China.

Consensus was found on only one clinical situation proposed as an element of a general definition in both countries: ‘extravasation of contrast on enema’ (Figure 2), and in the Netherlands on two additional elements: radiological collection for which percutaneous drainage was needed (50/59 respondents, 85%) and necrosis of the anastomosis visible upon reintervention (51/59 respondents, 86%). For all other items on the available general definitions, clinical and radiological diagnosis of CAL, no consensus was found. Scores were significantly different between China and the Netherlands for the following elements: radiological collection treated conservatively (21% vs 39%, respectively, P = 0.010), necrosis of the blind loop on reintervention (41% vs 69%, respectively, P ≤ 0.001), and air surrounding the anastomosis on a CT scan (65% vs 44%, respectively, P = 0.004).

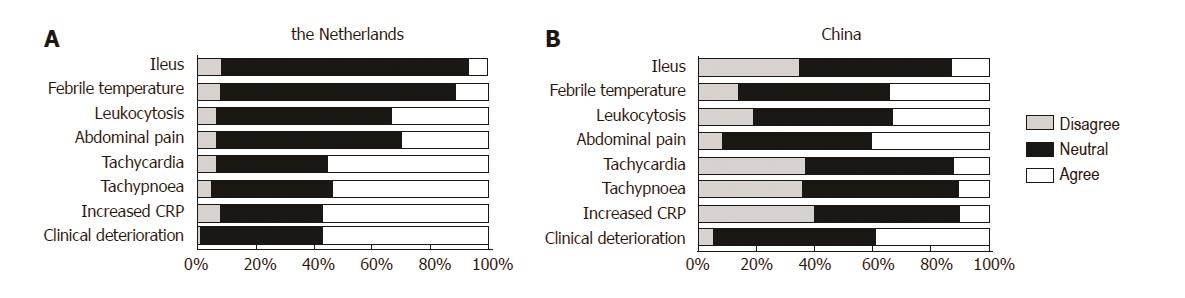

Grades given for the clinical parameters are shown in Figure 3 for both China and the Netherlands. Clinical deterioration, increased C-reactive protein (CRP), tachypnea, and tachycardia were seen as being most contributory for the clinical suspicion of CAL in the Netherlands, and were given a weighed score of 7.83, 7.45 7.13 and 7.13, respectively (Table 2). In China, clinical deterioration and abdominal pain other than wound pain were deemed most attributable for the suspicion of anastomotic leakage in the direct postoperative period, with scores of 6.67 and 6.61, respectively. Increased plasma concentration of CRP received the lowest score of all parameters in China (4.35), while in the Netherlands this was deemed more sensitive (7.45, P < 0.001). Upon categorization of the grades for the value of clinical parameters into different categories of the numeric scale: disagree (0-3), neutral (4-6) and agree (7-10), most surgeons from both countries (45%-59% of surgeons for each parameter) remained neutral towards the added value of specific clinical parameters during the postoperative course.

| Clinical parameter | China | The Netherlands | P-value |

| Score ± SD | Score ± SD | ||

| Increased CRP | 4.35 ± 2.466 | 7.45 ± 1.871 | < 0.001 |

| Leukocytosis | 5.96 ± 2.596 | 6.53 ± 1.824 | 0.095 |

| Tachycardia | 4.55 ± 2.411 | 7.13 ± 1.937 | < 0.001 |

| Tachypnea | 4.46 ± 2.244 | 7.13 ± 1.937 | < 0.001 |

| Febrile temperature | 6.23 ± 2.281 | 5.86 ± 1.963 | 0.207 |

| Postoperative ileus | 4.47 ± 2.363 | 5.76 ± 1.679 | < 0.001 |

| Clinical deterioration | 6.67 ± 2.033 | 7.83 ± 1.205 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 6.61 ± 2.247 | 6.74 ± 1.835 | 0.659 |

The data on radiodiagnostics are shown in Table 3. The majority of Chinese and Dutch surgeons perform radiodiagnostics upon clinical suspicion of a leak. The distribution of the answers over the different classifications, however, was significantly different between the two nationalities (Chi square test, P = 0.020). Expected false-negative rates for CT scans were equal for surgeons in both countries. A significantly larger portion of the Chinese colorectal surgeons (25.4% vs 13.6%, P ≤ 0.001) would consider performing a reoperation for the suspicion of CAL without performing radiological diagnostics. The distribution of the scores differed significantly between countries as to in how many cases a reoperation is considered without previous radiodiagnostics (Chi square test, P = 0.002).

| Responders, n (%) | China (%) | The Netherlands (%) | P-value |

| In how many percent of patients with clinical suspicion of anastomotic leakage do you perform radiodiagnostics? | |||

| 202 (100) | 55 (93) | ||

| 0%-20% | 3.0 | 0 | |

| 21%-40% | 6.4 | 0 | |

| 41%-60% | 6.9 | 1.8 | |

| 61%-80% | 24.3 | 16.4 | |

| 81%-100% | 59.4 | 81.8 | |

| Average | 83.3 | 91.5 | 0.285 |

| In how many percent of patients with clinical suspicion of anastomotic leakage do radiodiagnostics change your treatment policy? | |||

| 202 (100) | 54 (91.5) | ||

| 0%-20% | 10.9 | 13.0 | |

| 21%-40% | 9.9 | 5.6 | |

| 41%-60% | 27.7 | 44.4 | |

| 61%-80% | 30.2 | 25.9 | |

| 81%-100% | 26.7 | 11.1 | |

| Average | 63.6 | 55.9 | 0.028 |

| In how many cases did the CT scan report no anastomotic leakage while there finally was an anastomotic leakage? | |||

| 202 (100) | 52 (88.1) | ||

| 0%-20% | 40.6 | 51.9 | |

| 21%-40% | 29.2 | 28.8 | |

| 41%-60% | 25.2 | 15.4 | |

| 61%-80% | 4.0 | 1.9 | |

| 81%-100% | 1.0 | 1.9 | |

| Average | 31.8 | 28.7 | 0.221 |

| In how many percent of cases do you consider a reoperation without previous radiodiagnostics? | |||

| 202 (100) | 53 (89.8) | ||

| 0%-20% | 58.4 | 84.9 | |

| 21%-40% | 18.8 | 13.2 | |

| 41%-60% | 17.3 | 0 | |

| 61%-80% | 4.5 | 0 | |

| 81%-100% | 1.0 | 1.9 | |

| Average | 25.4 | 13.6 | < 0.001 |

Concerning the question about early CAL, 90.6% of the Chinese surgeons agreed that the cause of such should be considered a technical failure, whilst only 70.4% of the Dutch colorectal surgeons agreed to this statement (P ≤ 0.001).

Despite extensive research in the field of CAL, no international consensus regarding a practical definition exists, which limits the transparency and comparison of study outcomes. Several definitions of CAL have been proposed during the last decade[18,23], but review of the literature shows that newly published papers fail to adopt these definitions[24]. Instead, authors seem to prefer to use their own definitions or no definition at all[24]. It could be postulated that these previously proposed definitions were not yet implemented in clinical practice and (retrospective) research because of limited awareness of the existence of such a definition and/or lack of support from a large expert group.

Reports from Asian studies show CAL rates that are substantially lower than those reported by Western research groups[25]. This could partially be explained by demographic differences that exist in patient population, availability and use of diagnostic tools, or how perioperative care is structured. Another explanation could be that Chinese surgeons only report a leak as such when reintervention is required.

On the other hand, despite the lower prevalence of obesity in Asian countries, rates of type II diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome are relatively high due to ethnic and genetic factors. Indeed, Asians account for 60% of diabetes mellitus cases worldwide[26], which is considered an important risk factor for CAL[27,28]. Furthermore, the most common location of colorectal tumors in the Asian population is the left hemicolon[16,29], compared to the Western population, in which the predominant side is the right[29,30]. The literature shows a significantly higher CAL risk for surgeries on colorectal tumors located in the left hemicolon[31]. These regional differences therefore fail to completely explain the variation in reported CAL rates. It is very likely that important regional differences exist as to what is considered an anastomotic leak, i.e., Asian surgeons may report a leak mostly when a reintervention is required, while the Western surgeons may report latent leaks. In order to gain more insight into these differences in views, the present survey was conducted both in China and in the Netherlands, countries that are considered to be representative for their continent.

In the first part of the survey, surgeons were asked whether different statements including clinical and radiological signs and interventions regarding CAL should be considered anastomotic leakage. Of ten statements, only one was deemed as CAL by more than 80% of respondents in both countries: ‘Extravasation of contrast after rectal enema visible on a CT scan’. This is generally considered a radiological hallmark sign for anastomotic leakage after left-sided colorectal surgery and should naturally be included in a general definition. Moreover, other important and evident CAL signs including “Radiological collection around the anastomosis treated with percutaneous drainage” and “Necrosis of the anastomosis seen at reoperation” received more than 80% positive responses in the Netherlands, however, not in China, and thus were not considered as consent according to the predetermined criteria. Despite this, the majority of the Chinese surgeons also agreed on these items and their answers did not differ significantly from those of their Dutch colleagues. In conclusion, it seems that for the evident signs of CAL, the majority of surgeons from both countries have quite similar views.

“Radiological collection treated conservatively” was only considered to be CAL in 21% of the Chinese surgeons (versus 39% in the Netherlands), which is almost a consensus of NOT including this statement in a general definition of CAL. On the contrary, it is at least remarkable that in current grading systems, a radiological collection can be considered anastomotic leakage. As such this is reported as a grade A CAL according to the International Study group of Rectal Cancer (ISREC)[18] and gradeI-II CAL according the Clavien-Dindo Scale.

Despite the fact that only a minority of Dutch surgeons consider conservatively treated radiological collections as CAL, these numbers are higher than those among the Chinese. These differences in views regarding the subclinical signs of CAL may eventually lead to a significantly higher reported CAL rate in the Dutch studies than the Chinese ones. However, considering the fact that more than 30%[32] of the CAL do not require invasive intervention, the treatment provided by surgeons from both countries may eventually be similar, i.e., leading to a similar intervention rate for the complication. To rule out the reporting difference in this regard, one solution is to report complications with a Clavien-Dindo score higher than IIIa, which actually is also commonly accepted and applied in recent studies.

The second part of the survey focused mainly on clinical markers and parameters for CAL. Early clinical diagnosis of CAL remains a challenge for surgeons worldwide. Many clinical symptoms and biomarkers have been suggested as early signs of CAL[33-36]. However, previous studies of these parameters have shown that almost none of these parameters yield sufficient diagnostic accuracy to allow for a confirmative diagnosis[37]. This explains our findings that most surgeons do not base their diagnosis of CAL on these parameters, which results in a relatively low score of their contribution to the suspicion of CAL. Surgeons from both countries deemed “deterioration of clinical condition” as an important symptom of CAL, which further accentuates the complexity of CAL diagnosis based on its clinical manifestations. We believe the surgeons’ opinions indeed reflect the unsatisfactory status of CAL diagnosis, which stresses the need for further research in this field[38]. However, important differences exist between the two countries. Although surgeons from both countries agreed about the predictive value of higher temperature, abdominal pain other than wound pain, and increased leukocyte count, more than half of the clinical parameters scored significantly lower in China than in the Netherlands. Although these abnormal clinical manifestations are indeed very common after gastrointestinal surgery[39], it seems that they are considered less suggestive by the Chinese surgeons.

The third part of the survey focused on radiological tools used in the diagnosis of CAL. Based on the present data, the majority of the surgeons in both countries would perform radiological examination on patients in whom CAL was suspected (these numbers are slightly higher in the Netherlands), and more than half of the treatment plans would be changed after the imaging. In this regard, although differences have been found in the views of Chinese and Dutch surgeons regarding the definition of CAL, the treatment they provide is similar. However, our data also show that surgeons from both countries do not blindly rely on the results from radiodiagnostics. Instead, they state that in approximately 30% of the cases in which CAL is suspected, CAL is eventually diagnosed in spite of a negative radiological report. This correlates with previously reported false negative rates of CT scans[40]. Experience with inaccurate CT scan reports may be a reason for surgeons to consider reoperation without affirmative CT results, which according to the data, occurs in about 25% of cases.

Further research and education may facilitate the achievement of international consensus. However, definition without considerations of the practical issues in different regions is unlikely to gain sufficient popularity. In 2010, the ISREC proposed a graded system for the diagnosis and treatment of CAL[18]. Grade A CAL refers to anastomotic leakage for which no active therapeutic intervention is required. It seems that this grade correlates with the second statement “Radiological collection surrounding the anastomosis treated conservatively” that is not classified as CAL according to the majority of both Dutch and Chinese surgeons. This discrepancy between an established definition and the views of colorectal surgeons could partly explain why the ISREC definition has not been adopted in practice and science. In accordance with that, our survey clearly demonstrates how different practices may influence surgeons’ opinion.

For example, in the Netherlands the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program has been widely adopted for years, and recommends no abdominal drainage after surgery. In China, on the contrary, ERAS is less commonly implemented, and an intra-abdominal drain is often left in situ for longer periods after surgery. Moreover, CT imaging is less commonly used as radiodiagnostic for CAL, and laboratory analysis by means of CRP is not yet implemented in routine practice in many rural areas. This could explain why increased CRP was deemed least contributory in the diagnostic process in the present survey. These points, though small, significantly influenced the results, and would certainly impact the applicability of a proposed CAL definition.

To successfully embed a definition in clinical practice, research on CAL would greatly benefit from establishing a uniform definition and recording in national databases. We will therefore continue to perform an extensive and systematic literature review. The results from that review and the consensus assessment described in this paper will lead to an international Delphi analysis that will allow us to reach consensus on a new definition proposal that will be supported by a large panel of experts. We sincerely welcome others to participate in this further research, in order to formulate a new definition based on joint experience and opinions.

The most important limitations of the study are the following. The content of questionnaires is always susceptible to researcher imposition and there may be a level of subjectivity in the answers given. Furthermore, the relatively low numbers of respondents from both countries would have a negative influence of the generalizability of study results. Finally, the original questionnaire was constructed in English and translated into Dutch and Chinese, which could introduce bias and weaken the validity of comparisons between the countries. Finally, as some of the clinical parameters used in the questionnaire were derived from the DULK-score, which was constructed and validated in the Netherlands, it is plausible that the Dutch participants scored similarly on these items because they were familiar with the content of the DULK-score, because they have been (in)directly involved in the construction of the scoring system. However, the use of the DULK-score has not remained limited to the Netherlands, and it is unknown whether the subset of Dutch surgeons familiar with the DULK-score is higher than the number of Chinese surgeons who use this score routinely, and whether this difference is large enough to alter the data significantly.

In conclusion, no international consensus of a practical definition of CAL is yet available, which limits the transparency and comparison of published results. The present international online survey proves the inconsistent views as to what is considered CAL among surgeons in the Netherlands and China, and shows large differences between countries. Dutch surgeons are more likely to report ‘subclinical’ leaks as CAL, which partly explains the higher reported Dutch CAL rates. Surgeons from both countries rely on radiological diagnostics and laboratory parameters in the decision-making process, but are well aware of the limitations of these diagnostic aids. A Delphi analysis within a representative panel of colorectal surgeons is desired to develop a widely accepted definition of CAL.

The authors thank the Dutch Society of Gastro Intestinal Surgery and their subdivision, the Taskforce Coloproctology, and Taskforce Anastomotic Leakage, for their support during the survey.

Colorectal anastomotic leakage (CAL) is the most feared complication after colorectal surgery. No international consensus exists regarding a general definition of CAL.

Over the past decades, thousands of articles on CAL have been published. Unfortunately, a uniform and accepted worldwide definition of CAL is not available. This limits the transparency and comparison of study results and usefulness in clinical practice.

An international survey has been performed to identify the differences in reported definitions of CAL and to evaluate the opinions of expert leaders in both a Western and Eastern country.

The present international online survey proves the inconsistent views as to what is considered CAL among surgeons in the Netherlands and China, and shows large differences between the countries. This is in line with the current literature, since there is no uniform accepted definition worldwide. We therefore propose to perform a systematic literature review to identify the available definitions. The final stage is to perform a Delphi analysis within a representative panel of colorectal surgeons to develop a widely accepted definition of CAL.

CAL is the major complication after colorectal surgery with a stable incidence (1.5%-23%). It is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality, poor quality of life, and increased health expenditure. Since CAL influences the direct postoperative course and has recently been proven to impact oncological outcome as well, it is frequently used as an outcome measure in clinical studies.

In this study, the authors have presented a thorough and critical analysis of the availability of a definition of CAL and the opinions of both Dutch and Chinese surgeons regarding this definition.

| 1. | Kirchhoff P, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D. Complications in colorectal surgery: risk factors and preventive strategies. Patient Saf Surg. 2010;4:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bertelsen CA, Andreasen AH, Jørgensen T, Harling H; Danish Colorectal Cancer Group. Anastomotic leakage after curative anterior resection for rectal cancer: short and long-term outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:e76-e81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1150-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Govaert JA, Fiocco M, van Dijk WA, Scheffer AC, de Graaf EJ, Tollenaar RA, Wouters MW; Dutch Value Based Healthcare Study Group. Costs of complications after colorectal cancer surgery in the Netherlands: Building the business case for hospitals. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1059-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Hammond J, Lim S, Wan Y, Gao X, Patkar A. The burden of gastrointestinal anastomotic leaks: an evaluation of clinical and economic outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1176-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, Ho JW, Seto CL. Anastomotic leakage is associated with poor long-term outcome in patients after curative colorectal resection for malignancy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kulu Y, Tarantio I, Warschkow R, Kny S, Schneider M, Schmied BM, Büchler MW, Ulrich A. Anastomotic leakage is associated with impaired overall and disease-free survival after curative rectal cancer resection: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2059-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Mirnezami A, Mirnezami R, Chandrakumaran K, Sasapu K, Sagar P, Finan P. Increased local recurrence and reduced survival from colorectal cancer following anastomotic leak: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;253:890-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 747] [Cited by in RCA: 699] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bakker IS, Grossmann I, Henneman D, Havenga K, Wiggers T. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage and leak-related mortality after colonic cancer surgery in a nationwide audit. Br J Surg. 2014;101:424-432; discussion 432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, Steele RJ, Carlson GL, Winter DC. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg. 2015;102:462-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | den Dulk M, Witvliet MJ, Kortram K, Neijenhuis PA, de Hingh IH, Engel AF, van de Velde CJ, de Brauw LM, Putter H, Brouwers MA. The DULK (Dutch leakage) and modified DULK score compared: actively seek the leak. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e528-e533. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Buchs NC, Gervaz P, Secic M, Bucher P, Mugnier-Konrad B, Morel P. Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:265-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Law WL, Chu KW. Anterior resection for rectal cancer with mesorectal excision: a prospective evaluation of 622 patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:260-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Nagawa H. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after surgery for colorectal cancer: results of prospective surveillance. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sparreboom CL, Wu ZQ, Ji JF, Lange JF. Integrated approach to colorectal anastomotic leakage: Communication, infection and healing disturbances. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7226-7235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Goh KL, Quek KF, Yeo GT, Hilmi IN, Lee CK, Hasnida N, Aznan M, Kwan KL, Ong KT. Colorectal cancer in Asians: a demographic and anatomic survey in Malaysian patients undergoing colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:859-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Buscail E, Blondeau V, Adam JP, Pontallier A, Laurent C, Rullier E, Denost Q. Surgery for rectal cancer after high-dose radiotherapy for prostate cancer: is sphincter preservation relevant? Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:973-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, Holm T, Wong WD, Tiret E, Moriya Y. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 1101] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 19. | Reinke CE, Showalter S, Mahmoud NN, Kelz RR. Comparison of anastomotic leak rate after colorectal surgery using different databases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:638-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Adams K, Papagrigoriadis S. Little consensus in either definition or diagnosis of a lower gastro-intestinal anastomotic leak amongst colorectal surgeons. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:967-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vather R, Trivedi S, Bissett I. Defining postoperative ileus: results of a systematic review and global survey. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:962-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Duncan EA, Colver K, Dougall N, Swingler K, Stephenson J, Abhyankar P. Consensus on items and quantities of clinical equipment required to deal with a mass casualties big bang incident: a national Delphi study. BMC Emerg Med. 2014;14:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Peel AL, Taylor EW. Proposed definitions for the audit of postoperative infection: a discussion paper. Surgical Infection Study Group. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73:385-388. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bruce J, Krukowski ZH, Al-Khairy G, Russell EM, Park KG. Systematic review of the definition and measurement of anastomotic leak after gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1157-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Cong ZJ, Hu LH, Bian ZQ, Ye GY, Yu MH, Gao YH, Li ZS, Yu ED, Zhong M. Systematic review of anastomotic leakage rate according to an international grading system following anterior resection for rectal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Shetty AS, Nanditha A. Trends in prevalence of diabetes in Asian countries. World J Diabetes. 2012;3:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 27. | Lin X, Li J, Chen W, Wei F, Ying M, Wei W, Xie X. Diabetes and risk of anastomotic leakage after gastrointestinal surgery. J Surg Res. 2015;196:294-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Iancu C, Mocan LC, Todea-Iancu D, Mocan T, Acalovschi I, Ionescu D, Zaharie FV, Osian G, Puia CI, Muntean V. Host-related predictive factors for anastomotic leakage following large bowel resections for colorectal cancer. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17:299-303. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Qing SH, Rao KY, Jiang HY, Wexner SD. Racial differences in the anatomical distribution of colorectal cancer: a study of differences between American and Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:721-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 30. | Rabeneck L, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. Is there a true “shift” to the right colon in the incidence of colorectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1400-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sultan R, Chawla T, Zaidi M. Factors affecting anastomotic leak after colorectal anastomosis in patients without protective stoma in tertiary care hospital. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:166-170. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Joh YG, Kim SH, Hahn KY, Stulberg J, Chung CS, Lee DK. Anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic protectomy can be managed by a minimally invasive approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bellows CF, Webber LS, Albo D, Awad S, Berger DH. Early predictors of anastomotic leaks after colectomy. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Reisinger KW, Poeze M, Hulsewé KW, van Acker BA, van Bijnen AA, Hoofwijk AG, Stoot JH, Derikx JP. Accurate prediction of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery using plasma markers for intestinal damage and inflammation. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:744-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cini C, Wolthuis A, D’Hoore A. Peritoneal fluid cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases as early markers of anastomotic leakage in colorectal anastomosis: a literature review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1070-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Agilli M, Aydin FN. Methodologic approach to accurate prediction of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery using plasma markers for intestinal damage and inflammation. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pedersen T, Roikjær O, Jess P. Increased levels of C-reactive protein and leukocyte count are poor predictors of anastomotic leakage following laparoscopic colorectal resection. Dan Med J. 2012;59:A4552. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Daams F, Wu Z, Lahaye MJ, Jeekel J, Lange JF. Prediction and diagnosis of colorectal anastomotic leakage: A systematic review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;6:14-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Erb L, Hyman NH, Osler T. Abnormal vital signs are common after bowel resection and do not predict anastomotic leak. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:1195-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Doeksen A, Tanis PJ, Wüst AF, Vrouenraets BC, van Lanschot JJ, van Tets WF. Radiological evaluation of colorectal anastomoses. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:863-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Netherlands

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Giglio MV, Milone M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Huang Y