Published online Aug 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5823

Peer-review started: February 22, 2017

First decision: June 5, 2017

Revised: June 22, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: August 21, 2017

Processing time: 178 Days and 21.8 Hours

Tegafur-uracil has been reported to have only minor adverse effects and is associated with liver injury in 1.79% of Japanese patients. The development of tegafur-uracil-induced hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension is rare. Here, we report a case of a 74-year-old woman with rapidly developing tegafur-uracil-induced hepatic fibrosis. The patient had no history of liver disease and had been treated with tegafur-uracil for 8 mo after breast cancer surgery. The patient was admitted to our hospital for abdominal distension and leg edema associated with liver dysfunction. Computed tomography imaging revealed massive ascites and splenomegaly, and a non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis indicated advanced fibrosis. The histopathological findings revealed periportal fibrosis and bridging fibrosis with septation. The massive ascites resolved after discontinuing tegafur-uracil. These findings suggest that advanced hepatic fibrosis can develop from a relatively short-term administration of tegafur-uracil and that non-invasive assessment is useful for predicting hepatic fibrosis.

Core tip: This case report presents a rapid development of hepatic fibrosis induced by tegafur-uracil and the usefulness of a non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Tegafur-uracil is often administered in patients with various cancers; therefore, when liver dysfunction progresses in patients treated with tegafur-uracil, the development of hepatic fibrosis should be considered, even for short-term administration.

- Citation: Honda S, Sawada K, Hasebe T, Nakajima S, Fujiya M, Okumura T. Tegafur-uracil-induced rapid development of advanced hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(31): 5823-5828

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i31/5823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5823

Tegafur-uracil is used worldwide as a treatment for various cancers, such as those of the lung, colon, liver, and breast. The oral administration of tegafur-uracil has been reported to have only minor adverse effects and, as such, is considered suitable for long-term administration[1,2]. Studies with a special focus on drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and drug safety have reported that tegafur-uracil is associated with liver injury in 1.79% of Japanese patients. The development of associated advanced hepatic fibrosis is unusual. In fact, studies have shown that advanced hepatic fibrosis develops only after the long-term administration of tegafur-uracil[1,3]. Here, we report a case that rapidly progressed to advanced hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension. The patient had been treated with short-term tegafur-uracil chemotherapy, and a non-invasive assessment was useful for the diagnosis and prediction of hepatic fibrosis.

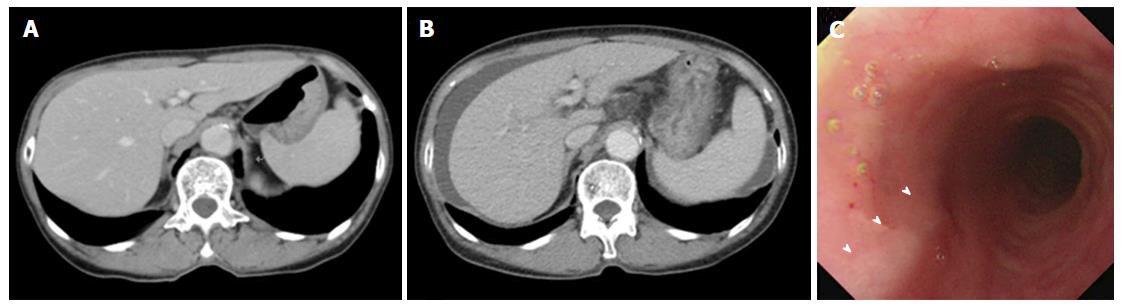

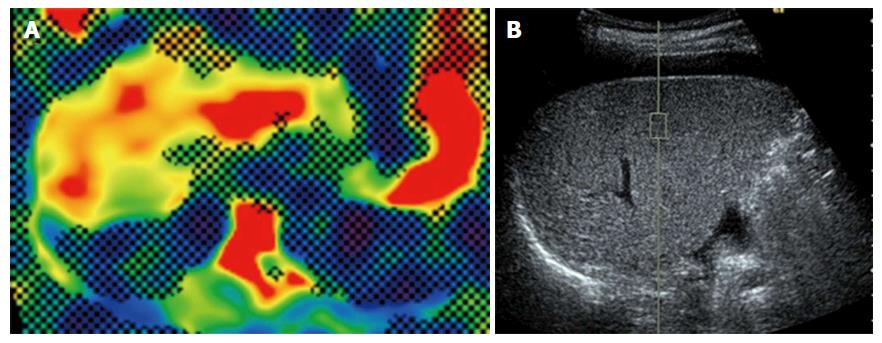

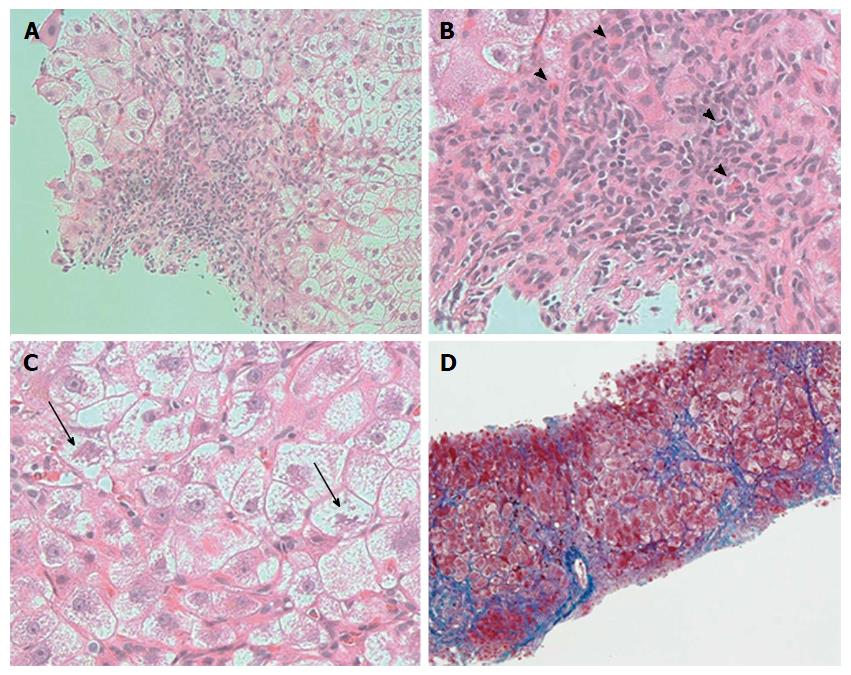

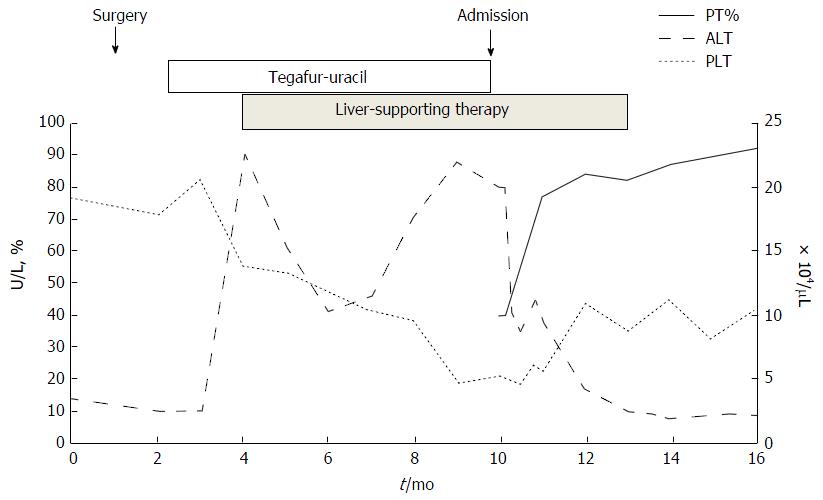

A 74-year-old woman who was treated with amlodipine for hypertension for more than 10 years was admitted to our hospital for abdominal distension and leg edema. The patient had undergone a muscle-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer in the left breast 9 mo prior. The histopathological examination showed stage I estrogen receptor- and progesterone receptor-negative apocrine carcinoma. The patient was therefore put on a regimen of tegafur-uracil (400 mg daily) for 8 mo. There was no history of liver disease or alcohol abuse, and there was no family history of liver disease. Before breast cancer surgery, computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated neither chronic liver disease nor splenomegaly (Figure 1A), and a blood examination showed normal platelet counts (19.2 × 104/μL), no coagulopathy (prothrombin time activity 104%), and no liver dysfunction (total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 22 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 14 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 320 mg/dL, gamma-glutamyl transferase 24 U/L). Two months after the administration of tegafur-uracil, her blood examination revealed increased serum transaminase levels. She was therefore prescribed ursodeoxycholic acid as a supportive liver therapy because of a suspicion of DILI. However, upon admission, her blood examination showed low platelet counts, persistent liver dysfunction, and increased levels of fibrosis markers such as type 4 collagen 7S and hyaluronic acid. The anti-hepatitis-B core (HBc) test was weakly positive; however, the HBV-DNA test was negative, suggesting a past infection (Table 1). CT imaging revealed the presence of massive ascites and splenomegaly (Figure 1B), and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed grade 1 esophageal varices without red spots (Figure 1C). The magnetic resonance (MR) elastography and Virtual Touch Quantification (VTQ) values were 7.0 kPa and 2.54 m/s, respectively (Figure 2A and B). These findings suggested that the patient had hepatic failure accompanied by portal hypertension and advanced hepatic fibrosis. Although her serum immunoglobulin levels were normal, she was positive for anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) (anti-centromere type) (Table 1). A liver biopsy was performed because primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) was suspected. Histopathological examination revealed spotty necrosis in zone 3 and interface hepatitis, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, all in zone 1 (Figure 3A and B). A Marked ballooning of hepatocytes with Mallory bodies was noted (Figure 3C). Periportal fibrosis and bridging fibrosis with partial septation were observed (Figure 3D). The intralobular bile ducts had partially degenerated, but neither chronic non-suppurative destructive cholangitis nor cholestasis were detected. There was no pathological copper or iron accumulation. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with tegafur-uracil-induced liver injury with a rapid development of advanced hepatic fibrosis. Discontinuation of tegafur-uracil combined with conservative treatment, including a diuretic, immediately improved the patient’s serum transaminase levels and prothrombin activity. The massive ascites was improved after 1 mo (Figure 4). Thirteen months after drug discontinuation, the patient’s type IV collagen 7S and hyaluronic acid levels were improved from 16 ng/mL to 6.5 ng/mL and from 653.4 ng/mL to 112.2 ng/mL, respectively, suggesting an alleviation of hepatic fibrosis.

| WBC | 5750/μL | ALP | 670 mg/dL | Type 4 collagen 7S | 16 ng/mL |

| RBC | 2.99 × 106/μL | LDH | 386 mg/dL | Hyaluronic acid | 653.4 ng/mL |

| Hb | 11.7 g/dL | γGTP | 97 U/L | ||

| PLT | 5.3 × 106/μL | ChE | 68 U/L | ANA | × 1280 |

| T. Cho | 120 g/dL | (anti-centromere type) | |||

| PT% | 40% | BUN | 18.6 mg/dL | AMA | (-) |

| PT-INR | 1.63 | Cre | 0.65 mg/dL | ASMA | (-) |

| Na | 140 mEq/L | ||||

| T.P. | 6.1 g/dL | K | 3.9 mEq/L | HBs Ag | (-) |

| Alb | 2.9 g/dL | Cl | 105 mEq/L | HBc Ab | 9.36 S/CO |

| T. Bil | 1.7 mg/dL | NH3 | 44 µg/dL | HBV DNA | (-) |

| D. Bil | 0.8 mg/dL | IgG | 1591.2 mg/dL | HCV Ab | (-) |

| AST | 130 U/L | IgA | 636.4 mg/dL | ||

| ALT | 80 U/L | IgM | 107.4 mg/dL |

Only five cases of tegafur-uracil-induced hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension have been described in the literature[1,3,4] (Table 2). These patients were treated with tegafur-uracil over a long period (23-54 mo; mean 39.6 mo), and their pathological findings showed periportal fibrosis and bridging fibrosis following liver biopsy. In our case, massive ascites, esophageal varices, and splenomegaly appeared 8 mo after drug administration. Hepatic fibrosis has been previously described in patients treated with tegafur-uracil over 23-54 mo, but the present case developed liver fibrosis only 8 mo after the administration of this medication, which suggested that a relatively short-term treatment with tegafur-uracil induced advanced hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension. We initially suspected tegafur-uracil-induced liver dysfunction on the basis of previous chronic liver disease. In particular, because anti-centromere type ANA is a significant risk factor for the development of portal hypertension in patients with PBC[5,6], we suspected PBC in this patient, and a liver biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination revealed the marked ballooning of hepatocytes and infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils. However, contrary to our expectations, features consistent with PBC were not observed. In addition, the patient did not have a history of chronic liver disease or alcohol abuse, and a previous CT imaging did not show chronic liver disease or splenomegaly. It is difficult to diagnose atypical PBC, even if historical analysis is performed; however, PBC usually develops slowly without an acute onset or acute exacerbation[7,8]. The clinical course necessitated the discontinuation of tegafur-uracil therapy. This treatment plan improved the patient’s liver dysfunction. Therefore, it appeared that advanced hepatic fibrosis was induced by the short-term administration of tegafur-uracil.

| Cases | Age (yr) | Sex | Daily dose (mg) | Duration (mo) | Type 4 collagen 7S (ng/mL) | Hepatic fibrosis | Portal hypertension |

| 1[1] | 81 | M | 400 | 48 | 12 | Bridging fibrosis | Esophageal varices |

| Ascites | |||||||

| 2[3] | 76 | F | NA | 24 | NA | Bridging fibrosis | Ascites |

| 3[4] | 82 | M | 300 | 48 | 12 | Bridging fibrosis | NA |

| 4[4] | 73 | M | 300 | 23 | 11 | Bridging fibrosis | NA |

| 5[4] | 68 | F | 400 | 55 | 12 | Bridging fibrosis | NA |

| Our case | 74 | F | 400 | 8 | 16 | Bridging fibrosis | Esophageal varices |

| With septation | Ascites | ||||||

| Splenomegaly |

Autoimmunity is related to liver injury induced by some drugs, such as herbal products, minocycline, diclofenac, statins, and other biological agents[9,10]. In our case, the mechanism underlying the rapid development of hepatic fibrosis was unclear. However, certain mechanisms that underlie autoimmune reactions may have been associated with the rapid progression of fibrosis.

Recent studies have suggested that non-invasive assessments of liver fibrosis, including approaches that use MR elastography[11,12] and VTQ[13-15], are useful for predicting hepatic fibrosis in patients with liver disease, particularly in those with chronic hepatitis C. Suou et al[1,4] reported that hepatic fibrosis without elevated transaminase levels could be induced by the long-term oral administration of tegafur-uracil and that certain serum fibrosis markers, such as type IV collagen 7S, were useful for the diagnosis of tegafur-uracil-induced hepatic fibrosis[1,4]. In our case, serum fibrosis markers, MR elastography, and VTQ indicated the presence of advanced hepatic fibrosis. Histopathological findings from liver biopsy specimens supported the findings obtained using the abovementioned techniques. These data suggest that non-invasive approaches may be useful in diagnosing hepatic fibrosis in patients with DILI.

In conclusion, our case suggests that short-term treatment with tegafur-uracil may lead to the rapid development of hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension. Tegafur-uracil can occasionally induce liver injury, which may develop into advanced hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension. However, hepatic fibrosis is not evaluated in many cases. Thus, when liver dysfunction progresses in patients who are treated with tegafur-uracil even for short periods, oncologists should consider hepatic fibrosis and perform a non-invasive assessment to rule out this possibility.

A 74-year-old Japanese woman who was treated with tegafur-uracil for 8 mo after breast cancer surgery presented with abdominal distension and leg edema.

Massive ascites and leg edema.

Primary biliary cholangitis.

Laboratory examination revealed low platelet counts, liver dysfunction, and high hepatic fibrosis markers such as type 4 collagen 7S and hyaluronic acid.

CT imaging revealed massive ascites and splenomegaly, and both of MR elastography and VTQ indicated advanced hepatic fibrosis.

Pathological examination revealed bridging fibrosis with septation, suggesting advanced hepatic fibrosis.

Discontinuation of tegafur-uracil combined with conservative treatment.

Some studies have shown the development of hepatic fibrosis induced by tegafur-uracil. However, all of the previously described patients had been treated with tegafur-uracil for a long period of time.

Tegafur-uracil has minor adverse effects and is associated with liver injury in only 1.79% of Japanese patients. Tegafur-uracil-induced hepatic fibrosis is rare.

The present case suggests that tegafur-uracil may lead to the rapid development of hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension, even when administered for a short period of time.

This is a well written case report. The case is rare and unusual in view of the rapid progression of the fibrosis.

| 1. | Suou T, Tanaka K, Okano J, Shiota G, Horie Y, Horie Y, Kawasaki H. A case with hepatic fibrosis showing ascites and esophageal varices induced by oral UFT(R) administration. Hepatol Res. 2002;22:161-165. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Palmeri S, Gebbia V, Russo A, Armata MG, Gebbia N, Rausa L. Oral tegafur in the treatment of gastrointestinal tract cancers: a phase II study. Br J Cancer. 1990;61:475-478. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kobayashi F, Ikeda T, Sakamoto N, Kurosaki M, Tozuka S, Sakamoto S, Fukuma T, Marumo F, Sato C. Severe chronic active hepatitis induced by UFTR containing tegafur and uracil. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2434-2437. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Suou T, Maruyama S, Nakamura H, Kishimoto Y, Abe J, Tanida O, Yamada S, Kawasaki H. Increase in serum 7S domain of type IV collagen and N-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen levels with normal serum transaminase levels after long-term oral administration of Tegaful-Uracil. Hepatol Res. 2002;24:184. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Nakamura M, Kondo H, Mori T, Komori A, Matsuyama M, Ito M, Takii Y, Koyabu M, Yokoyama T, Migita K. Anti-gp210 and anti-centromere antibodies are different risk factors for the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:118-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ishibashi H, Komori A, Shimoda S, Ambrosini YM, Gershwin ME, Nakamura M. Risk factors and prediction of long-term outcome in primary biliary cirrhosis. Intern Med. 2011;50:1-10. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kaplan MM. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1570-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Neuberger J. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 1997;350:875-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ortega-Alonso A, Stephens C, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Case Characterization, Clinical Features and Risk Factors in Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:pii: E714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | deLemos AS, Foureau DM, Jacobs C, Ahrens W, Russo MW, Bonkovsky HL. Drug-induced liver injury with autoimmune features. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:194-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shire NJ, Yin M, Chen J, Railkar RA, Fox-Bosetti S, Johnson SM, Beals CR, Dardzinski BJ, Sanderson SO, Talwalkar JA. Test-retest repeatability of MR elastography for noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment in hepatitis C. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:947-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Motosugi U, Ichikawa T, Sano K, Sou H, Muhi A, Koshiishi T, Ehman RL, Araki T. Magnetic resonance elastography of the liver: preliminary results and estimation of inter-rater reliability. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:623-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Friedrich-Rust M, Nierhoff J, Lupsor M, Sporea I, Fierbinteanu-Braticevici C, Strobel D, Takahashi H, Yoneda M, Suda T, Zeuzem S. Performance of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse imaging for the staging of liver fibrosis: a pooled meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:e212-e219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kircheis G, Sagir A, Vogt C, Vom Dahl S, Kubitz R, Häussinger D. Evaluation of acoustic radiation force impulse imaging for determination of liver stiffness using transient elastography as a reference. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1077-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Nightingale K. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) Imaging: a Review. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2011;7:328-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Buechler C, Snyder N S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D