Published online Aug 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5634

Peer-review started: May 28, 2017

First decision: June 23, 2017

Revised: June 29, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: August 14, 2017

Processing time: 80 Days and 1 Hours

To critically review the literature addressing the definition, epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO).

A systematic search was performed to identify articles investigating the aetiology and pathophysiology of ACPO. A narrative synthesis of the evidence was undertaken.

No consistent approach to the definition or reporting of ACPO has been developed, which has led to overlapping investigation with other conditions. A vast array of risk factors has been identified, supporting a multifactorial aetiology. The pathophysiological mechanisms remain unclear, but are likely related to altered autonomic regulation of colonic motility, in the setting of other predisposing factors.

Future research should aim to establish a clear and consistent definition of ACPO, and elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to altered colonic function. An improved understanding of the aetiology of ACPO may facilitate the development of targeted strategies for its prevention and treatment.

Core tip: Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, though the underlying pathophysiology remains poorly understood. An abundance of risk factors and associated conditions have been identified, strongly suggesting a multifactorial origin, and likely culminating in an imbalance in autonomic nervous supply to the colon. Future areas for research are identified and may allow for the development of novel therapeutic or preventative strategies.

- Citation: Wells CI, O’Grady G, Bissett IP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A systematic review of aetiology and mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(30): 5634-5644

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i30/5634.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5634

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO) is a rare condition characterised by acute colonic dilatation in the absence of mechanical obstruction. It was first described by Sir William Ogilvie in 1948, in two patients with malignant infiltration of the pre-vertebral ganglia[1].

ACPO usually occurs in hospitalised patients with severe illness or trauma, or following general, orthopaedic, neurosurgical, gynaecological or other surgical procedures, with an estimated incidence of 100 cases per 100000 admissions and a mortality rate of 8%[2,3]. Colonic ischaemia or perforation occurs in up to 15%, and is associated with an estimated 40% mortality[4-6]. Therefore, early recognition and appropriate therapy are important determinants of prognosis[2].

The pathophysiology underlying ACPO is poorly understood, with the prevailing hypothesis being an imbalance in colonic autonomic innervation[2,4]. Progress has been limited by a rudimentary understanding of the complex processes regulating colonic motility patterns, the lack of specific animal models for ACPO, and the poor quality of evidence arising from case reports and uncontrolled case series.

An improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying ACPO may aid the development of novel management strategies for this condition. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to critically review the literature addressing the definition, epidemiology, risk factors, aetiology and pathophysiology of ACPO with a view to informing knowledge gaps and identifying priority areas for future research.

A systematic search of the Ovid MEDLINE and Embase databases was performed from inception to 25 May 2017, using the search terms “Ogilvie’s syndrome”, “pseudoobstruction”, and “pseudo obstruction”. Google Scholar was also searched using free text entries. Identified articles were screened by title and abstract for inclusion, with subsequent acquisition of full texts. The reference lists of included papers were manually searched, and a hand search of the scientific literature was performed to identify additional relevant publications.

Non-English articles were excluded. There were no exclusion limits by study design; both primary research and review articles were eligible. Full-text articles were evaluated for evidence addressing the definition, epidemiology, risk factors, aetiology and pathogenesis of ACPO. Clinical management has recently been reviewed in depth[7-9], and was beyond the scope of this study, though pathophysiological hypotheses drawn from this evidence were evaluated. A narrative synthesis of the identified evidence was undertaken.

ACPO is characterised by acute colonic dilatation in the absence of intrinsic mechanical obstruction or extrinsic inflammatory process[10]. ACPO should be distinguished from other acute conditions, such as toxic megacolon, which may have inflammatory or infective causes, as well as chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) and other causes of megacolon.

Many overlapping terms have been used in the literature to describe ACPO since its original description, reflecting the uncertainly regarding its precise aetiology (Table 1). The term “intestinal pseudo-obstruction” was first proposed by Dudley in 1958[11], with “ACPO” not appearing for another twenty years[4]. Use of “Ogilvie’s syndrome” has been discouraged due to ambiguity regarding its meaning[12], though considerable heterogeneity in terminology still exists in recent literature[3,13,14].

| Term | Ref. |

| Large intestine colic | [1] |

| Ogilvie’s syndrome | [4, 153, 155-157] |

| Pseudo-megacolon | [158] |

| Adynamic ileus | [159, 160] |

| Paralytic ileus | [14, 142] |

| Functional obstruction of the intestinal tract | [161] |

| Idiopathic large bowel obstruction | [154] |

| Colonic ileus | [160, 162-164] |

| Intestinal pseudo-obstruction | [11, 111, 146, 165, 166] |

| Non-mechanical large bowel obstruction | [167] |

| Pseudo-obstruction of the large bowel, pseudo-obstruction of the colon | [23, 86, 140, 141, 168, 169] |

| Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction | [4] |

| Non-obstructive colonic dilatation | [170, 171] |

| Malignant ileus | [144] |

| Cecal ileus | [164] |

| Acute megacolon | [81, 172] |

Inconsistent terminology has contributed to inconsistency in research and reporting. No standardised clinical definition or diagnostic criteria for ACPO were identified[15], preventing reliable synthesis of data on risk factors or therapeutic strategies[7,8]. Some studies failed to distinguish ACPO from CIPO and other forms of megacolon[10,16], despite these being distinct entities with different mechanisms and therapies[17,18].

ACPO is uncommon, with an identified incidence of approximately 100 cases per 100000 inpatient admissions[3]. A recent US study reported a declining mortality rate associated with ACPO from 9.4% in 1998 to 6.4% in 2011, although over-diagnosis may have contributed[3]; historically mortality rates were as high as 30%[4]. Colonic perforation and ischemia occur in 10%-20%, with an associated mortality of up to 45%[2,4]. Rates of surgical and endoscopic intervention have declined in recent decades, due to an increasing focus on conservative management and pharmacological therapy with neostigmine[3].

ACPO disproportionately affects elderly and comorbid patients; often those with an acute illness on a background of chronic cardiac, respiratory or neurological disease. ACPO also occurs following general, orthopaedic, neurosurgical, cardiothoracic and gynaecological procedures[19]. Vanek et al[2] reported 400 cases of ACPO, with approximately 50% resulting from acute medical illness and 50% from post-surgical patients. Incidence rates have been described in spinal or orthopaedic surgery (1%-2%)[13,20], cardiac bypass (up to 5%)[21], and following burn injuries (0.3%)[22]. An abundance of other conditions associated with ACPO were found to have been reported in the literature, the most common of which are summarised (Table 2).

| Category | Risk factors |

| Surgical | Cardiac surgery, solid organ transplantation, major orthopaedic surgery, spine surgery |

| Cardiorespiratory | Shock, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Neurological | Dementia, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, spinal cord injury |

| Metabolic | Electrolyte imbalance, diabetes, renal failure, hepatic failure |

| Medications | Opiates, anti-Parkinson agents, anticholinergics, antipsychotics, cytotoxic chemotherapy, clonidine |

| Obstetric/gynaecological | Caesarean section, normal vaginal delivery, instrumental delivery, preeclampsia, normal pregnancy, pelvic surgery |

| Infectious | Varicella-zoster virus, herpes virus, cytomegalovirus |

| Miscellaneous | Major burns/trauma, severe sepsis, idiopathic |

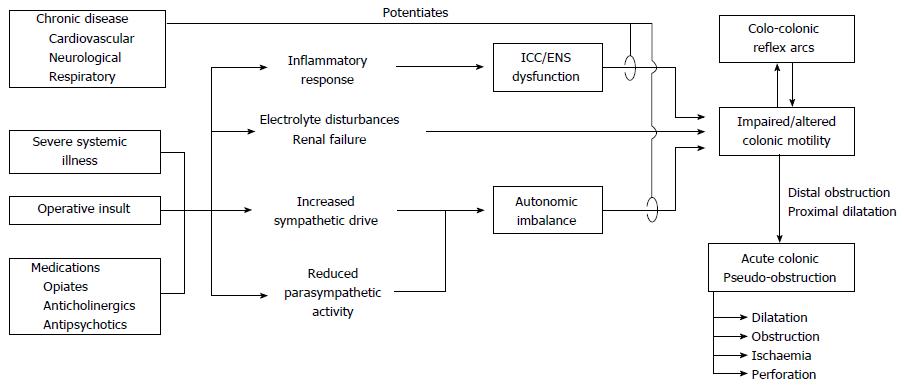

Review of the literature revealed a vast array of risk factors for ACPO, supporting a multifactorial aetiology with several pathways leading to a common effect on colonic motor function[23] (Figure 1). However, few published studies were found directly investigating the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ACPO, with the majority of evidence inferred from basic physiology and other disease states such as post-operative ileus (POI). No animal models of ACPO were identified.

Normal colonic motor activity is regulated at several levels; (1) colonic smooth muscle; (2) pacemaker activity generated by interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC); (3) intrinsic control via the enteric nervous system (ENS); (4) prevertebral and spinal reflex arcs; and (5) extrinsic modulation by the autonomic nervous system and hormonal systems. Being a “functional obstruction”, ACPO is presumed to result from aberrations in colonic motor activity, though physiological data specifically characterising these abnormalities was not identified.

Altered extrinsic regulation of colonic function by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems is the most commonly suggested mechanism for ACPO[10,24-29]. This mechanism was first postulated by Ogilvie, who proposed a “sympathetic deprivation” of the colon[1]. Current theory favours a relative excess of sympathetic over parasympathetic tone, though it is unclear whether this is due to increased sympathetic activity, reduced parasympathetic signalling, both, or either. The prevailing hypothesis remains that ACPO is the result of reduced parasympathetic innervation to the distal colon, leading to an atonic segment and functional obstruction[2,10,27,28,30-32]; however no published physiological data was found to directly support or refute this claim[28,29].

The colon receives sympathetic innervation from the prevertebral ganglia (proximally via the superior mesenteric ganglion; distally via the inferior mesenteric ganglion). Nerve fibres follow the respective arterial routes[33], and the proximal colon appears to have a richer sympathetic innervation[23]. The parasympathetic supply to the mid-gut is via the vagus nerve while the hind-gut is innervated by sacral parasympathetic outflow (S2-4)[33], although animal studies have demonstrated some overlap between these distributions[34]. The transition point from distended to normal colon in ACPO usually occurs near the splenic flexure[2,10,35], where there is a transition in the innervation for both sympathetic and parasympathetic supply to the colon, supporting autonomic imbalance as a key step in pathogenesis.

Most patients with ACPO are unwell with major illness, therefore having increased systemic sympathetic drive[23,36,37], potentially contributing to autonomic imbalance at the level of the colon. Other reported cases have involved pathology potentially disrupting the autonomic supply to the colon, such as retroperitoneal tumours or haemorrhage[38,39]. Interestingly, ACPO cannot be reproduced in humans or animals by splanchnic or pelvic nerve transection[40,41], thus the pathogenesis appears more complex than excess or deficiency of sympathetic or parasympathetic activity alone.

Neostigmine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and parasympathomimetic commonly used in management of ACPO, further supporting autonomic imbalance as a key pathophysiological mechanism. Early studies investigated use of guanethidine, a sympatholytic, followed by neostigmine[42]. Guanethidine was later shown ineffective[43], while neostigmine has been proven efficacious in several randomised trials[7,44-46]. Prior studies have shown that parasympathetic stimulation with neostigmine triggers colonic high amplitude propagating sequences (HAPS) in both dogs and humans[47,48], which has been proposed as a possible mechanism for its decompressive effect in the functionally obstructed colon[49]. However, HAPS primarily arise in the proximal colon, and it is unknown what effect neostigmine has on other prominent colonic motor activity such as cyclic events, or the role of these events in ACPO[50].

Several spinal and ganglionic reflex arcs are involved in regulating intestinal motor function. The colo-colonic inhibitory reflex refers to inhibition of proximal colonic motor activity in response to distal colonic distention[51,52]. Conversely, proximal distension also causes a reduction in basal intraluminal pressure in the distal colon[51]. Evidence from animal models suggests these reflex arcs are mediated via afferent mechanoreceptors synapsing with adrenergic efferent neurons in the prevertebral ganglia and spinal cord[18,51,52].

These reflexes provide a possible mechanism to explain how disordered motility and distension of one colonic region may potentiate dilatation of other regions, contributing to ACPO[18,26,28,30]. Some authors have pointed to the therapeutic success of epidural anaesthesia and splanchnic nerve block in case reports as evidence for this mechanism[10,53], though it is difficult to ascertain whether this is due to disruption of the efferent limb of these reflex arcs, or simply reduction in the extrinsic sympathetic supply to the colon. Furthermore, epidural anaesthesia has been implicated as both a cause of and a therapy for ACPO[18,53,54]. The lack of high-quality evidence identified in this area makes it difficult to determine the effects of spinal or ganglionic blockade in ACPO and the precise role of the colo-colonic inhibitory reflex.

ICC are the pacemaker responsible for generating electrical slow waves, which are modulated by the ENS, resulting in the rhythmic contractile activity of the intestine[55,56]. Despite their recognised importance in the control of gastrointestinal motility, few studies were identified that specifically investigated the roles of enteric neurons or ICC in ACPO.

Permanent impairment of the ENS, ICC, and/or myopathy characterises many forms of CIPO[24,57-59]. However, the acute onset, reversibility, and different epidemiology of ACPO implies a distinct pathophysiological process from CIPO, hence these findings should not be extrapolated to the acute form of pseudo-obstruction.

Jain et al[57] investigated ICC using immunohistochemistry in patients with pseudo-obstruction syndromes, showing two patients with ACPO had a normal number and distribution of ICC. However, whether ICC function is affected in ACPO remains unknown. Choi et al[35] reported a reduction and degeneration of enteric ganglionic cells in the resected colonic specimens of four patients with pseudo-obstruction, but it is unclear whether these patients had ACPO or CIPO, and whether these histological abnormalities represent cause or effect of the colonic dilatation and pseudo-obstruction. Without further pathophysiological studies, the role of the ENS and ICC in the development of ACPO remains unknown.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important inhibitory neurotransmitter released by colonic enteric neurons, and has been implicated in colonic dilatation and dysfunction in toxic megacolon[37,60,61] and colitis[62]. Several authors have speculated whether NO may also have a role in ACPO, however no physiological evidence was found to support this claim. However, polyethylene glycol (PEG), an osmotic laxative that may also reduce NO production[63,64], has been shown to reduce relapse rates after decompression in ACPO[65]. This finding could be explained by either the laxative effects of PEG or its effect on nitrinergic signalling. A number of novel pharmacological treatments targeting NO regulation have recently been discovered, though no studies were identified that applied these therapies in patients with ACPO[66].

Notably, many ACPO patients are elderly and have chronic cardiac, respiratory or neurological disease, with onset often occurring in the context of a further acute physiological insult[2,3]. Chronic stress conditioning, similar to the effects of chronic disease, potentiates excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission[67], potentially explaining these associations. The ENS and its extrinsic regulation are affected in several conditions commonly associated with ACPO, including diabetes mellitus[68,69], Parkinson’s[70,71] and Alzheimer’s disease[70,72,73]. Furthermore, both the ENS and ICC have been shown to degenerate with age[74-76], which may partly account for the elderly preponderance of this disorder[2,3,29,77].

Patients with chronic conditions are also more likely to be on multiple medications affecting colonic motility[78,79], and may therefore be predisposed to the development of ACPO. Numerous medications have been associated with ACPO, including anticholinergics, opiates, calcium channel blockers, and psychotropic drugs[80-82]. Furthermore, use of anti-motility agents is predictive of poor response to neostigmine[83], while methylnaltrexone has been successfully used in a patient with ACPO who failed to respond to two doses of neostigmine[84].

Many medications associated with ACPO modulate the autonomic nervous system, supporting disruption of these pathways as a key pathophysiological mechanism. Clonidine[18,85-87] and amitraz[88] are α2-adrenergic agonists that have been associated with ACPO. At the level of the colon, α2-adrenergic signalling reduces release of acetylcholine from enteric neurons, resulting in a relative imbalance of sympathetic over parasympathetic supply[89,90], consistent with current theory regarding the pathophysiology of ACPO.

The operation most commonly resulting in ACPO is caesarean section[2,26,91-99], but ACPO also occurs after normal and instrumental vaginal delivery[100-102]. A recent systematic review identified that preeclampsia, multiple pregnancy, and antepartum haemorrhage/placenta praevia appear to be more common in women who develop ACPO following caesarean section[103]. However, it remains unclear how these events result in acutely perturbed colonic function. Some authors have proposed that compression of parasympathetic plexuses by the gravid uterus may contribute[26,27,104], while others have hypothesised that the uterus may fall back into the pelvis following delivery, causing a mechanical obstruction at the rectosigmoid colon[36,105].

Pregnancy is also associated with high levels of progesterone and glucagon, both of which have been shown to diminish the tone of the large bowel[92], and may predispose to ACPO when combined with acute physiological disturbances such as caesarean section, preeclampsia, peripartum sepsis, or haemorrhage. Resting sympathetic vasomotor outflow is increased during the third trimester, even in women with normal blood pressure[106,107], while autonomic dysfunction and sympathetic overactivity are a feature of severe preeclampsia[108,109]. It is unknown whether sympathetic supply to the colon is also affected in these states, but this could plausibly contribute to autonomic imbalance and ACPO. Finally, prostaglandins are intimately involved in parturition[110], and have also been suggested as a possible contributor to ACPO in obstetric patients[92] (discussed in next section).

A disrupted “milieu interieur” is common in ACPO, which may precipitate or exacerbate the effects of altered autonomic function or other mechanisms. A host of metabolic factors have been shown to influence colonic motility, though few studies have investigated these specifically in ACPO. However, the isolated colonic dysfunction characterising ACPO makes it unlikely that metabolic abnormalities are the sole pathophysiological explanation.

Renal failure and electrolyte disturbances often accompany ACPO, although it has been disputed whether this is a cause or effect of the pseudo-obstruction[4,16,32,39,83,111]. Alterations in potassium and other electrolyte concentrations affect ion channel function and may alter ICC pacemaker or smooth muscle activity[112,113]. Furthermore, electrolyte imbalance has been identified as a predictor of a poor clinical response to neostigmine[83].

Prostaglandins and cytokines are both well-established inflammatory mediators of gastrointestinal motility[114,115]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β have implicated in POI[114,115], but have not yet been investigated in ACPO. Prostaglandins have been implicated in POI[115,116], CIPO[117,118], acute small intestinal dysmotility[119], and also affect ICC function and slow wave frequency[120]. However, no studies were identified investigating the role of prostaglandins in the development of ACPO. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression is increased in the distended colon of mice with experimentally-induced mechanical obstruction, and it has been suggested that this is responsible for reduced motility via the effects of prostaglandin E2[121]. However, caution must be taken when extrapolating these results to humans and to ACPO[122].

ACPO has also been associated with several viral infections, most commonly herpes zoster reactivation in low thoracic or lumbar distributions[123-130], but also disseminated varicella zoster[131-134], acute cytomegalovirus[135], and severe dengue[136].

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain these associations, all involving autonomic dysfunction. Reactivation of herpes virus in enteric ganglia may result in a sympathetic autonomic neuritis[123,124,137,138], presumably diminishing colonic sympathetic supply. Local segmental colonic inflammation with afferent stimuli to the sacral nerve roots and blockage of colonic parasympathetic supply has also been suggested[138], while other authors have hypothesised that viral spread from the dorsal root ganglia to the thoracolumbar or sacral lateral columns may interrupt sacral parasympathetic pathways[137]. Involvement and inflammation of the intrinsic enteric nervous system, and post-viral dysautonomia have also been suggested[136,137,139].

Several alternate hypotheses regarding the pathophysiology of ACPO were identified. Compromised vascular supply to the colon was suggested in many early reports[11,140,141], but now thought to represent an exacerbating complication rather than a cause. “Hinge-kinking” of the colon at the transition from retro- to intra-peritoneal structures has also been proposed[142], however, intra-operative and radiological findings generally suggest a “gradual” transition in colonic calibre[23]. Other identified hypotheses lacking supporting evidence included the “air-fluid lock syndrome”[143-145], and colonic distension due to aerophagy in chronic respiratory disease[146,147].

Despite considerable speculation, this comprehensive and systematic review of the literature finds that the mechanisms underpinning ACPO still remain uncertain. Limited physiological evidence from patients with ACPO was found to exist, and the lack of an animal model has required extrapolation of data from other disease states. The abundance of identified risk factors and associated conditions supports a multifactorial hypothesis, with aberrations in function at any of several levels seemingly able to lead to common or similar effects on the colon.

Overall, autonomic imbalance is the most strongly supported pathophysiological contributor, and likely plays a key role in the development of ACPO. Evidence supporting a major role for autonomic imbalance includes the observation that most patients with ACPO are systemically unwell, or have other pathology disrupting the autonomic supply to the colon. Furthermore, the transition point from distended to normal colon in ACPO usually occurs at the splenic flexure, corresponding to the change in autonomic innervation of the mid-gut and hind-gut. However, the precise aberrations in autonomic function leading to ACPO remain unclear.

ACPO is difficult to rigorously investigate due to its acute and sporadic nature and heterogeneity. The plethora of case reports identified in the literature is testament to the large number of illnesses associated with this condition. It is also clear that a categorical clinical definition of ACPO is needed to standardise research, and improve the quality of published evidence. Distinct subtypes of ACPO have recently been proposed according to gut wall thickness on cross-sectional imaging[148], and further work should investigate the aetiology and prognostic significance of this phenomenon.

Importantly, the precise aberrations in colonic motor activity underlying ACPO have not been characterised. Despite the common assumption that the distal colon is atonic, direct physiological evidence supporting this claim could not be identified, and it remains unknown whether ACPO is fundamentally due to atony, dysmotility, or spasm in part or all of the colon, or is due to heterogeneous motility states. Furthermore, although many authors have argued that the sympathetic system decreases colonic motility and the parasympathetic increases contractility[10,18,28,30,43], this is now recognised as overly simplistic, with further layers of modulation within the ENS, ICC and smooth muscle[27,33]. It is also important to note that the therapeutic success of neostigmine also does not specifically prove interrupted parasympathetic supply to the colon as the sole pathophysiological mechanism underlying ACPO[29], despite this being suggested by many authors[2,42,43,149,150]. Indeed, provocation of HAPS and colonic emptying by neostigmine may be sufficient to overcome an alternative pathophysiological mechanism and result in decompression of the functionally obstructed colon.

High-resolution colonic manometry has recently been used to characterise the abnormalities underlying colonic dysmotility in the early post-operative period, demonstrating increased cyclic motor activity in the left colon, rather than atony, and an absence of HAPS[151,152]. Applying similar research methods to ACPO would be a particularly interesting research avenue, with potential to rigorously define the altered motility patterns underlying the disorder. It is interesting to note that transient “ring[s] of spasm” were noted intra-operatively in the distal colon of several of the original descriptions of this syndrome[1,153,154], though the pathophysiological significance of these remains unclear. Other areas for future pathophysiological investigation include the development of an animal model of ACPO, histological examination of resected specimens, and rigorous investigation of the impact of preventative or therapeutic strategies on colonic function.

This systematic review and appraisal of the literature surrounding ACPO has identified limited evidence investigating the mechanisms underlying this condition. A number of areas for further study have been identified. It is hoped that an improved understanding of the pathophysiology of ACPO will lead to the development of targeted strategies for its prevention and treatment.

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO) is an uncommon condition, characterised by acute colonic dilatation in the absence of a mechanical obstruction. Colonic ischaemia or perforation may occur in up to 15% of patients, and is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.

The pathophysiology underlying ACPO is poorly understood, with a plethora of associated conditions reported in the literature. The prevailing hypothesis is an imbalance in colonic autonomic innervation, though few articles have thoroughly examined the evidence supporting this claim.

This systematic review finds that the mechanisms underpinning ACPO still remain uncertain. Autonomic imbalance is the most strongly supported pathophysiological factor, though the precise aberrations leading to ACPO are unclear. A number of other factors may contribute to ACPO, including colonic reflex arcs, intrinsic colonic dysfunction, chronic disease, and pharmacological or metabolic disturbances.

A number of areas for future investigation have been identified, including the use of high-resolution colonic manometry to rigorously define the altered motility patterns underlying ACPO, the development of an animal model, and histological examination of resected specimens. An improved understanding of the pathophysiology of ACPO may lead to the development of novel preventative or therapeutic strategies.

Pseudo-obstruction is characterised by a clinical presentation suggestive of intestinal obstruction, in the absence of a mechanically obstructing lesion. ACPO is the acute form of colonic pseudo-obstruction, while chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction is a distinct entity with different mechanisms and therapies. “Ogilvie’s syndrome” has also been used to refer to ACPO, though this term is now discouraged due to ambiguity regarding its meaning.

This is a very interesting review regarding the etiology of acute colonic pseudo obstruction. The author introduced a number of articles regarding this issue.

| 1. | Ogilvie H. Large-intestine colic due to sympathetic deprivation; a new clinical syndrome. Br Med J. 1948;2:671-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:203-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ross SW, Oommen B, Wormer BA, Walters AL, Augenstein VA, Heniford BT, Sing RF, Christmas AB. Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction: Defining the Epidemiology, Treatment, and Adverse Outcomes of Ogilvie’s Syndrome. Am Surg. 2016;82:102-111. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Nanni G, Garbini A, Luchetti P, Nanni G, Ronconi P, Castagneto M. Ogilvie’s syndrome (acute colonic pseudo-obstruction): review of the literature (October 1948 to March 1980) and report of four additional cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:157-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M. Pseudo-obstruction in the critically ill. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:427-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Colonic pseudo-obstruction: the dilated colon in the ICU. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003;14:20-27. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Valle RG, Godoy FL. Neostigmine for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2014;3:60-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kayani B, Spalding DR, Jiao LR, Habib NA, Zacharakis E. Does neostigmine improve time to resolution of symptoms in acute colonic pseudo-obstruction? Int J Surg. 2012;10:453-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Elsner JL, Smith JM, Ensor CR. Intravenous neostigmine for postoperative acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:430-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pereira P, Djeudji F, Leduc P, Fanget F, Barth X. Ogilvie’s syndrome-acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dudley HA, Sinclair IS, Mclaren IF, Mcnair TJ, Newsam JE. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1958;3:206-217. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Vavilala MS, Lam AM. Neostigmine for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1622; author reply 1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Januszewski J, Keem SK, Smith W, Beckman JM, Kanter AS, Oskuian RJ, Taylor W, Uribe JS. The Potentially Fatal Ogilvie’s Syndrome in Lateral Transpsoas Access Surgery: A Multi-Institutional Experience with 2930 Patients. World Neurosurg. 2017;99:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Khan MW, Ghauri SK, Shamim S. Ogilvie’s Syndrome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26:989-991. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sloyer AF, Panella VS, Demas BE, Shike M, Lightdale CJ, Winawer SJ, Kurtz RC. Ogilvie’s syndrome. Successful management without colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1391-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Durai R. Colonic pseudo-obstruction. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:237-244. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Stanghellini V. Neuro-immune interactions in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Auton Res. 2010;20:123. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Romeo DP, Solomon GD, Hover AR. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: a possible role for the colocolonic reflex. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tenofsky PL, Beamer L, Smith RS. Ogilvie syndrome as a postoperative complication. Arch Surg. 2000;135:682-686; discussion 686-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Norwood MG, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:496-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Simić O, Strathausen S, Hess W, Ostermeyer J. Incidence and prognosis of abdominal complications after cardiopulmonary bypass. Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7:419-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kadesky K, Purdue GF, Hunt JL. Acute pseudo-obstruction in critically ill patients with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995;16:132-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bardsley D. Pseudo-obstruction of the large bowel. Br J Surg. 1974;61:963-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bernardi MP, Warrier S, Lynch AC, Heriot AG. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85:709-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chudzinski AP, Thompson EV, Ayscue JM. Acute colonic pseudoobstruction. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2015;28:112-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reeves M, Frizelle F, Wakeman C, Parker C. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction in pregnancy. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85:728-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jain A, Vargas HD. Advances and challenges in the management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ogilvie syndrome). Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:37-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chapple K. Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction. In: Brown SR, Hartley JE, Hill J, Scott N, Williams JG. Contemporary Coloproctology: Springer, 2012: 439-449. . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | De Giorgio R, Knowles CH. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Br J Surg. 2009;96:229-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Saunders MD. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:671-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tack J. Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction (Ogilvie’s Syndrome). Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:361-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Systematic review: acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:917-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mathias CJ, Bannister R. Autonomic failure: a textbook of clinical disorders of the autonomic nervous system. 5th ed. OUP Oxford, 2013. . |

| 34. | Tong WD, Ridolfi TJ, Kosinski L, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Effects of autonomic nerve stimulation on colorectal motility in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Choi JS, Lim JS, Kim H, Choi JY, Kim MJ, Kim NK, Kim KW. Colonic pseudoobstruction: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1521-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dorudi S, Berry AR, Kettlewell MG. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Br J Surg. 1992;79:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | De Giorgio R, Barbara G, Stanghellini V, Tonini M, Vasina V, Cola B, Corinaldesi R, Biagi G, De Ponti F. Review article: the pharmacological treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1717-1727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Saunders MD. Acute colonic pseudoobstruction. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:410-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Jetmore AB, Timmcke AE, Gathright JB Jr, Hicks TC, Ray JE, Baker JW. Ogilvie’s syndrome: colonoscopic decompression and analysis of predisposing factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1135-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gribovskaja-Rupp I, Takahashi T, Ridolfi T, Kosinski L, Ludwig K. Upregulation of mucosal 5-HT3 receptors is involved in restoration of colonic transit after pelvic nerve transection. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:472-478, e218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Furness JB, Callaghan BP, Rivera LR, Cho H-J. The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: integrated local and central control. In: Lyte M, Cryan JF. Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease. Springer, 2014: 39-71. . [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Hutchinson R, Griffiths C. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: a pharmacological approach. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:364-367. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Stephenson BM, Morgan AR, Salaman JR, Wheeler MH. Ogilvie’s syndrome: a new approach to an old problem. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ponec RJ, Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Amaro R, Rogers AI. Neostigmine infusion: new standard of care for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:304-305. [PubMed] |

| 46. | van der Spoel JI, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Stoutenbeek CP, Bosman RJ, Zandstra DF. Neostigmine resolves critical illness-related colonic ileus in intensive care patients with multiple organ failure--a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:822-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Leelakusolvong S, Bharucha AE, Sarr MG, Hammond PI, Brimijoin S, Phillips SF. Effect of extrinsic denervation on muscarinic neurotransmission in the canine ileocolonic region. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:173-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Law NM, Bharucha AE, Undale AS, Zinsmeister AR. Cholinergic stimulation enhances colonic motor activity, transit, and sensation in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1228-G1237. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Bharucha AE. High amplitude propagated contractions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:977-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Dinning PG, Wiklendt L, Maslen L, Gibbins I, Patton V, Arkwright JW, Lubowski DZ, O’Grady G, Bampton PA, Brookes SJ. Quantification of in vivo colonic motor patterns in healthy humans before and after a meal revealed by high-resolution fiber-optic manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1443-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kreulen DL, Szurszewski JH. Reflex pathways in the abdominal prevertebral ganglia: evidence for a colo-colonic inhibitory reflex. J Physiol. 1979;295:21-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hughes SF, Scott SM, Pilot MA, Williams NS. Adrenoceptors and colocolonic inhibitory reflex. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2462-2468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lee JT, Taylor BM, Singleton BC. Epidural anesthesia for acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:686-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mashour GA, Peterfreund RA. Spinal anesthesia and Ogilvie’s syndrome. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:122-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Mostafa RM, Moustafa YM, Hamdy H. Interstitial cells of Cajal, the Maestro in health and disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3239-3248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 56. | Al-Shboul OA. The importance of interstitial cells of cajal in the gastrointestinal tract. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Jain D, Moussa K, Tandon M, Culpepper-Morgan J, Proctor DD. Role of interstitial cells of Cajal in motility disorders of the bowel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:618-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Coulie B, Camilleri M. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:37-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Farrugia G. Interstitial cells of Cajal in health and disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20 Suppl 1:54-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Mourelle M, Casellas F, Guarner F, Salas A, Riveros-Moreno V, Moncada S, Malagelada JR. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in colonic smooth muscle from patients with toxic megacolon. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1497-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Mourelle M, Vilaseca J, Guarner F, Salas A, Malagelada JR. Toxic dilatation of colon in a rat model of colitis is linked to an inducible form of nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:G425-G430. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Onori L, Aggio A, D’Alo’ S, Muzi P, Cifone MG, Mellillo G, Ciccocioppo R, Taddei G, Frieri G, Latella G. Role of nitric oxide in the impairment of circular muscle contractility of distended, uninflamed mid-colon in TNBS-induced acute distal colitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5677-5684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | de Winter BY, van Nassauw L, de Man JG, de Jonge F, Bredenoord AJ, Seerden TC, Herman AG, Timmermans JP, Pelckmans PA. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of septic ileus in mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:251-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Shishido SM, de Oliveira MG. Polyethylene glycol matrix reduces the rates of photochemical and thermal release of nitric oxide from S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;71:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sgouros SN, Vlachogiannakos J, Vassiliadis K, Bergele C, Stefanidis G, Nastos H, Avgerinos A, Mantides A. Effect of polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution on patients with acute colonic pseudo obstruction after resolution of colonic dilation: a prospective, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:638-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Savidge TC. Importance of NO and its related compounds in enteric nervous system regulation of gut homeostasis and disease susceptibility. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;19:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Kimoto M, Zeredo JL, Ota MS, Nihei Z, Toda K. Comparison of stress-induced modulation of smooth-muscle activity between ileum and colon in male rats. Auton Neurosci. 2014;183:8-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Horváth VJ, Putz Z, Izbéki F, Körei AE, Gerő L, Lengyel C, Kempler P, Várkonyi T. Diabetes-related dysfunction of the small intestine and the colon: focus on motility. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Yarandi SS, Srinivasan S. Diabetic gastrointestinal motility disorders and the role of enteric nervous system: current status and future directions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:611-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Rao M, Gershon MD. The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:517-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Lebouvier T, Chaumette T, Paillusson S, Duyckaerts C, Bruley des Varannes S, Neunlist M, Derkinderen P. The second brain and Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:735-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Puig KL, Lutz BM, Urquhart SA, Rebel AA, Zhou X, Manocha GD, Sens M, Tuteja AK, Foster NL, Combs CK. Overexpression of mutant amyloid-β protein precursor and presenilin 1 modulates enteric nervous system. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:1263-1278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Semar S, Klotz M, Letiembre M, Van Ginneken C, Braun A, Jost V, Bischof M, Lammers WJ, Liu Y, Fassbender K. Changes of the enteric nervous system in amyloid-β protein precursor transgenic mice correlate with disease progression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:7-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Camilleri M, Cowen T, Koch TR. Enteric neurodegeneration in ageing. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:418-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Wade PR, Cowen T. Neurodegeneration: a key factor in the ageing gut. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16 Suppl 1:19-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Gibbons SJ, Sarr MG, Kendrick ML, Shen KR, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, Larson DW, Ordog T, Pozo MJ. Changes in interstitial cells of cajal with age in the human stomach and colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:36-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Wegener M, Börsch G. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Presentation of 14 of our own cases and analysis of 1027 cases reported in the literature. Surg Endosc. 1987;1:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Jain V, Pitchumoni CS. Gastrointestinal side effects of prescription medications in the older adult. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Triantafyllou K, Vlachogiannakos J, Ladas SD. Gastrointestinal and liver side effects of drugs in elderly patients. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:203-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Catchpole BN. Pseudo-obstruction. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292:1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Alam HB, Fricchione GL, Guimaraes AS, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 31-2009. A 26-year-old man with abdominal distention and shock. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1487-1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Fahy BG. Pseudoobstruction of the colon: early recognition and therapy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1996;8:133-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Mehta R, John A, Nair P, Raj VV, Mustafa CP, Suvarna D, Balakrishnan V. Factors predicting successful outcome following neostigmine therapy in acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:459-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Weinstock LB, Chang AC. Methylnaltrexone for treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:883-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Bauer GE, Hellestrand KJ. Letter: Pseudo-obstruction due to clonidine. Br Med J. 1976;1:769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Bear R, Steer K. Pseudo-obstruction due to clonidine. Br Med J. 1976;1:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Stieger DS, Cantieni R, Frutiger A. Acute colonic pseudoobstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) in two patients receiving high dose clonidine for delirium tremens. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:780-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Aslan S, Bilge F, Aydinli B, Ocak T, Uzkeser M, Erdem AF, Katirci Y. Amitraz: an unusual aetiology of Ogilvie’s syndrome. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:481-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Doherty NS, Hancock AA. Role of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors in the control of diarrhea and intestinal motility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;225:269-274. [PubMed] |

| 90. | Nagao M, Shibata C, Funayama Y, Fukushima K, Takahashi KI, Jin XL, Kudoh K, Sasaki I. Role of alpha-2 adrenoceptors in regulation of giant migrating contractions and defecation in conscious dogs. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2204-2210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Paraskevaides EC, Sodipo JA. Atypical Ogilvie syndrome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;28:148-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Dickson MA, McClure JH. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction after caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1994;3:234-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Busch FW, Hamdorf JM, Carroll CS Sr, Magann EF, Morrison JC. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following cesarean delivery. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2004;45:323-326. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Saha AK, Newman E, Giles M, Horgan K. Ogilvie’s syndrome with caecal perforation after Caesarean section: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:6177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Shakir AJ, Sajid MS, Kianifard B, Baig MK. Ogilvie’s syndrome-related right colon perforation after cesarean section: a case series. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:234-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Latunde-Dada AO, Alleemudder DI, Webster DP. Ogilvie’s syndrome following caesarean section. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Suraweera P, Davis L, Gulfraz F, Lahiri S. Ogilvie’s syndrome after caesarean section-case report and review of the literature. BJOG. 2013;120:39. |

| 98. | Yulia A, Guirguis M. Ogilvie syndrome - An acute pseudo-colonic obstruction 1 week following caesarean section: A case report. BJOG. 2012;119:32-33. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Srivastava G, Pilkington A, Nallala D, Polson DW, Holt E. Ogilvie’s syndrome: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276:555-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Bhatti AB, Khan F, Ahmed A. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO) after normal vaginal delivery. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:138-139. [PubMed] |

| 101. | Cartlidge D, Seenath M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the large bowel with caecal perforation following normal vaginal delivery: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Kakarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, Ash A. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome) following instrumental vaginal delivery. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:1303-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Jayaram P, Mohan M, Lindow S, Konje J. Postpartum Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction (Ogilvie’s Syndrome): A systematic review of case reports and case series. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;214:145-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Ravo B, Pollane M, Ger R. Pseudo-obstruction of the colon following cesarean section. A review. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:440-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Munro A, Jones PF. Abdominal surgical emergencies in the puerperium. Br Med J. 1975;4:691-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Fu Q, Levine BD. Autonomic circulatory control during pregnancy in humans. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:330-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Greenwood JP, Stoker JB, Walker JJ, Mary DA. Sympathetic nerve discharge in normal pregnancy and pregnancy-induced hypertension. J Hypertens. 1998;16:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Schobel HP, Fischer T, Heuszer K, Geiger H, Schmieder RE. Preeclampsia -- a state of sympathetic overactivity. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1480-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Airaksinen KE, Kirkinen P, Takkunen JT. Autonomic nervous dysfunction in severe pre-eclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985;19:269-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Chang SW, Ohara N. Pulmonary intravascular phagocytosis in liver disease. Clin Chest Med. 1996;17:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Lowman RM. The potassium depletion states and postoperative ileus. The role of the potassium ion. Radiology. 1971;98:691-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Quigley EM. Acute Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2000;3:273-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Akiho H, Ihara E, Motomura Y, Nakamura K. Cytokine-induced alterations of gastrointestinal motility in gastrointestinal disorders. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2011;2:72-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Vather R, O’Grady G, Bissett IP, Dinning PG. Postoperative ileus: mechanisms and future directions for research. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41:358-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Bauer AJ, Schwarz NT, Moore BA, Türler A, Kalff JC. Ileus in critical illness: mechanisms and management. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Luderer JR, Demers LM, Bonnem EM, Saleem A, Jeffries GH. Elevated prostaglandin e in idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Book LS, Johnson DG, Jubiz W. Elevated prostaglandin E in children with chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction syndrome (CIIPS): Effects of prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors on gastrointestinal motility. Clin Res. 1979;27:100A. |

| 119. | Chousterman M, Petite JP, Housset E, Hornych A. Prostaglandins and acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Lancet. 1977;2:138-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Xue S, Valdez DT, Tremblay L, Collman PI, Diamant NE. Electrical slow wave activity of the cat stomach: its frequency gradient and the effect of indomethacin. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1995;7:157-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Shi XZ, Lin YM, Powell DW, Sarna SK. Pathophysiology of motility dysfunction in bowel obstruction: role of stretch-induced COX-2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G99-G108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Lee E, Lee J, Do YS, Myung SJ, Yu CS, Lee HK. Distribution of COX-2 and collagen accumulation in the dilated colons obtained from patients with chronic colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastroenterology. 2016;1:S537. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Kesner KM, Bar-Maor JA. Herpes zoster causing apparent low colonic obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:503-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Johnson JN, Sells RA. Herpes zoster and paralytic ileus: a case report. Br J Surg. 1977;64:143-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Caccese WJ, Bronzo RL, Wadler G, McKinley MJ. Ogilvie’s syndrome associated with herpes zoster infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 126. | Alpay K, Yandt M. Herpes zoster and Ogilvie’s syndrome. Dermatology. 1994;189:312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Pai NB, Murthy RS, Kumar HT, Gerst PH. Association of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) with herpes zoster. Am Surg. 1990;56:691-694. [PubMed] |

| 128. | Jucgla A, Badell A, Ballesta C, Arbizu T. Colonic pseudo-obstruction: a complication of herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:788-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | Rodrigues G, Kannaiyan L, Gopasetty M, Rao S, Shenoy R. Colonic pseudo-obstruction due to herpes zoster. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2002;21:203-204. [PubMed] |

| 130. | Masood I, Majid Z, Rind W, Zia A, Riaz H, Raza S. Herpes Zoster-Induced Ogilvie’s Syndrome. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:563659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 131. | Walsh TN, Lane D. Pseudo obstruction of the colon associated with varicella-zoster infection. Ir J Med Sci. 1982;151:318-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 132. | Nomdedéu JF, Nomdedéu J, Martino R, Bordes R, Portorreal R, Sureda A, Domingo-Albós A, Rutllant M, Soler J. Ogilvie’s syndrome from disseminated varicella-zoster infection and infarcted celiac ganglia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:157-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 133. | Carrascosa MF, Salcines-Caviedes JR, Román JG, Cano-Hoz M, Fernández-Ayala M, Casuso-Sáenz E, Abascal-Carrera I, Campo-Ruiz A, Martín MC, Díaz-Pérez A. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection as a possible cause of Ogilvie’s syndrome in an immunocompromised host. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2718-2721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 134. | Braude MR, Trubiano JA, Heriot A, Dickinson M, Carney D, Seymour JF, Tam CS. Disseminated visceral varicella zoster virus presenting with the constellation of colonic pseudo-obstruction, acalculous cholecystitis and syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion. Intern Med J. 2016;46:238-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 135. | Shapiro AM, Bain VG, Preiksaitis JK, Ma MM, Issa S, Kneteman NM. Ogilvie’s syndrome associated with acute cytomegaloviral infection after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2000;13:41-45. [PubMed] |

| 136. | Anam AM, Rabbani R. Ogilvie’s syndrome in severe dengue. Lancet. 2013;381:698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 137. | Edelman DA, Antaki F, Basson MD, Salwen WA, Gruber SA, Losanoff JE. Ogilvie syndrome and herpes zoster: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:696-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 138. | Tribble DR, Church P, Frame JN. Gastrointestinal visceral motor complications of dermatomal herpes zoster: report of two cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 139. | Pui JC, Furth EE, Minda J, Montone KT. Demonstration of varicella-zoster virus infection in the muscularis propria and myenteric plexi of the colon in an HIV-positive patient with herpes zoster and small bowel pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1627-1630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 140. | Vedin A, Wilhelmson C, Werko L. Pseudo-obstruction of the Large Bowel. Br Med J. 1975;2: 105. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 141. | Addison NV. Pseudo-obstruction of the large bowel. J R Soc Med. 1983;76:252-255. [PubMed] |

| 142. | Byrne JJ. Unusual aspects of large bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 1962;103:62-65. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 143. | Singleton AO Jr, Wilson M. Air-fluid obstruction of the colon. South Med J. 1967;60:909-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 144. | Hubbard CN, Richardson EG. Pseudo-obstruction of the colon. A postoperative complication in orthopaedic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:226-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 145. | Gammill SL. Air-fluid lock syndrome. Radiology. 1974;111:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 147. | Ferguson JH, Cameron A. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Br Med J. 1973;1:614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 148. | Zhao C, Xie T, Li J, Cheng M, Shi J, Gao T, Xi F, Shen J, Cao C, Yu W. Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction with Feeding Intolerance in Critically Ill Patients: A Study according to Gut Wall Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:9574592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 149. | Batke M, Cappell MS. Adynamic ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:649-670, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 150. | Stephenson BM, Morgan AR, Wheeler MH. Parasympathomimetics in Ogilvie’s syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:289-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 151. | Lin AY, Dinning PG, Milne T, Bissett IP, O’Grady G. The “rectosigmoid brake”: review of an emerging neuromodulation target for colorectal functional disorders. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44:719-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 152. | Vather R, Lin A, O’Grady G, Dinning P, Rowbotham D, Bissett I. Perioperative Colonic Motility defined by High-Resolution Manometry After Intestinal Surgery. Proceedings of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Annual Meeting;2016 Apr 30-May 4; Los Angeles, CA, USA. Wolters Kluwer, 2016: e167. . |

| 153. | Macfarlane JA, Kay SK. Ogilvie’s syndrome of false colonic obstruction; is it a new clinical entity? Br Med J. 1949;2:1267-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 154. | Rothwell-jackson RL. Idiopathic large-bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 1963;50:797-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 155. | Dunlop JA. Ogilvie’s syndrome of false colonic obstruction; a case with post-mortem findings. Br Med J. 1949;1:890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 156. | Gerlis LM. Ogilvie’s syndrome. Br Med J. 1949;1:1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 157. | Abrahams AM. Ogilvie’s syndrome. Br Med J. 1950;4653:606. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 158. | Creech B. Megacolon; a review of the literature and report of a case in the aged. N C Med J. 1950;11:241-246. [PubMed] |

| 159. | Moore CE, Koman GM. Impending cecal perforation secondary to a crushing injury of the pelvis. Arch Surg. 1959;79:1044-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 160. | Adams JT. Adynamic ileus of the colon. An indication for cecostomy. Arch Surg. 1974;109:503-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 161. | Melamed M, KUBIAN E. Relationship of the autonomic nervous system to “functional” obstruction of the intestinal tract. Report of four cases, one with perforation. Radiology. 1963;80:22-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 163. | Bryk D, Soong KY. Colonic ileus and its differential roentgen diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1967;101:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 164. | Johnson CD, Rice RP, Kelvin FM, Foster WL, Williford ME. The radiologic evaluation of gross cecal distension: emphasis on cecal ileus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:1211-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 165. | Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction. Br Med J. 1973;1:64-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 166. | Romeo DP, Solomon GD, Hover AR. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 167. | Gillett DJ. Non-mechanical large-bowel obstruction. Aust N Z J Surg. 1971;41:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 168. | Soreide O, Bjerkeset T, Fossdal JE. Pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilve’s syndrome), a genuine clinical conditions? Review of the literature (1948-1975) and report of five cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;20:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 169. | Bachulis BL, Smith PE. Pseudoobstruction of the colon. Am J Surg. 1978;136:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 170. | Strodel WE, Nostrant TT, Eckhauser FE, Dent TL. Therapeutic and diagnostic colonoscopy in nonobstructive colonic dilatation. Ann Surg. 1983;197:416-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 171. | Koneru B, Selby R, O’Hair DP, Tzakis AG, Hakala TR, Starzl TE. Nonobstructing colonic dilatation and colon perforations following renal transplantation. Arch Surg. 1990;125:610-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 172. | Adeyanju MA, Bello AO. Acute megacolon (acute colonic pseudo-obstruction)- a case report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2013;2:485-488. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: New Zealand

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0