Published online Aug 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i29.5386

Peer-review started: March 23, 2017

First decision: April 21, 2017

Revised: May 3, 2017

Accepted: June 19, 2017

Article in press: June 19, 2017

Published online: August 7, 2017

Processing time: 139 Days and 12.5 Hours

To compare the outcomes of preoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD).

Data from 153 consecutive patients who underwent preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage prior to PD between January 2009 and July 2016 were analyzed. We compared the clinical data, procedure-related complications of endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD) and postoperative complications of PD between the ENBD and ERBD groups. Univariate and multivariate analyses with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were used to identify the risk factors for deep abdominal infection after PD.

One hundred and two (66.7%) patients underwent ENBD, and 51 (33.3%) patients underwent ERBD. Endoscopic sphincterotomy was less frequently performed in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group (P = 0.039); the EBD duration in the ENBD group was shorter than that in the ERBD group (P = 0.036). After EBD, the levels of total bilirubin (TB) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were obviously decreased in both groups, and the decreases of TB and ALT in the ERBD group were greater than those in the ENBD group (P = 0.004 and P = 0.000, respectively). However, the rate of EBD procedure-related cholangitis was significantly higher in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group (P = 0.007). The postoperative complications of PD as graded by the Clavien-Dindo classification system were not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.864). However, the incidence of deep abdominal infection after PD was significantly lower in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group (P = 0.019). Male gender (OR = 3.92; 95%CI: 1.63-9.47; P = 0.002), soft pancreas texture (OR = 3.60; 95%CI: 1.37-9.49; P = 0.009), length of biliary stricture (≥ 1.5 cm) (OR = 5.20; 95%CI: 2.23-12.16; P = 0.000) and ERBD method (OR = 4.08; 95%CI: 1.69-9.87; P = 0.002) were independent risk factors for deep abdominal infection after PD.

ENBD is an optimal method for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD. ERBD is superior to ENBD in terms of patient tolerance and the effect of biliary drainage but is associated with an increased risk of EBD procedure-related cholangitis and deep abdominal infection after PD.

Core tip: To compare the outcomes of preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage via endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), we studied 153 patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction who underwent ENBD or ERBD prior to PD. ERBD was superior to ENBD in terms of patient tolerance and the effect of biliary drainage, but the incidence rates of endoscopic biliary drainage procedure-related complications and deep abdominal infection after PD were higher than those associated with ENBD. Multivariate analysis showed that ERBD was an independent risk factor for deep abdominal infection after PD. ENBD is the optimal method for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD.

- Citation: Zhang GQ, Li Y, Ren YP, Fu NT, Chen HB, Yang JW, Xiao WD. Outcomes of preoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage and endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage for malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(29): 5386-5394

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i29/5386.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i29.5386

Malignant distal biliary obstruction, which is caused by periampullary carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma and other malignant diseases, can lead to obstructive jaundice. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is the curative treatment for malignant distal biliary obstruction. Hyperbilirubinemia causes organ dysfunction, including liver and cardiac dysfunction, as well as coagulation dysfunction, bacterial translocation and cholangitis. Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) can reduce serum bilirubin levels, which may improve the outcomes of surgical treatment[1]. However, controversy regarding the use of PBD for malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD has existed for decades. Some studies found that PBD did not improve the outcomes of surgery but did increase postoperative complications (infectious complication, postoperative pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, etc.) and hospitalization, and PBD was considered a negative prognostic factor for the long-term survival of patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction after PD. Therefore, some researchers suggested that PBD should be avoided or should not be performed routinely in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction after PD[2-6]. No consensus regarding whether to perform PBD for malignant obstructive jaundice has been established. However, PBD is still used at many centers for patients presenting with hyperbilirubinemia or cholangitis to improve their preoperative state. PBD can be performed via endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD) or via percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD). EBD has been shown to be superior to PTBD for the treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD because PTBD is more invasive and is associated with a higher rate of complications and higher incidence of catheter tract metastasis[7,8]. Several recent reports have shown that EBD is the preferred method because patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction who undergo PTBD prior to PD have poorer long-term survival than those who undergo EBD[9-12]. EBD can be performed via endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) with a nasobiliary catheter or via endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) with a plastic stent. There is debate regarding which is the more beneficial method for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction, and several papers have suggested that ENBD is superior to ERBD when considering the incidence of stent dysfunction, perioperative complication rate and mortality[13,14].

In the present study, we retrospectively investigated the outcomes of EBD via ENBD with a nasobiliary catheter and ERBD with a plastic stent in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD.

Between January 2009 and July 2016, a prospectively collected database of patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction who had undergone EBD prior to PD (Whipple) at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University was retrospectively reviewed. EBD was performed for patients with hyperbilirubinemia and poor liver function prior to PD. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. A total of 153 patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction (total bilirubin ≥ 100 μmol/L) underwent EBD (ENBD or ERBD). The ENBD group was matched in a 2:1 ratio to the ERBD group with respect to patient clinical characteristics, data of EBD and PD. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was performed in patients with severe stenosis when balloon dilatation was not possible. We used a 7.5-Fr tube in the ENBD group and an 8.5-Fr plastic stent in the ERBD group. After the drainage procedure, the surgeon evaluated the patients regarding bilirubin to determine whether the surgical goals were achieved or whether the drainage was dysfunctional, after which PD was performed.

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data, including age, gender, concomitant diseases (hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, acute pancreatitis and cholangitis), biochemical indicators [total bilirubin (TB) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)], EBD-related data (the type and diameter of the nasobiliary catheter and plastic stent and the length of the biliary stricture), PD-related data (pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct diameter, common bile duct diameter, operative time, bleeding volume, and blood transfusion), the complications of EBD and the postoperative complications of PD.

The complications of EBD included stent/tube dysfunction, pancreatitis, cholangitis and others (hemorrhage, perforation, etc.). Stent/tube dysfunction included occlusion or migration that prevented the serum bilirubin and transaminase from decreasing or increasing. Pancreatitis was characterized by upper abdominal pain, abdominal distension, vomiting and other clinical symptoms, including serum amylase concentration that was three or more times higher than the upper limit of normal. Cholangitis was characterized by fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain with an increase in white blood cell count.

The postoperative complications of PD included pancreatic fistula (PF), delayed gastric emptying (DGE), postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH), bile leakage, deep abdominal infection, wound infection and pneumonia. According to the guidelines of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula, PF was confirmed when the concentration of amylase in the peritoneal drainage fluid or abdominal puncture fluid was three or more times higher than the upper limit of the normal serum concentration after postoperative day 3, and PF was divided into three grades (A, B and C) based on clinic symptoms and treatment[15]. DGE and PPH were also diagnosed according to the ISGPS guidelines and were also divided into three grades (A, B and C)[16,17]. Bile leakage was diagnosed when bile was present in the drainage fluid or abdominal puncture fluid. Deep abdominal infections, including peritoneal infection and intra-abdominal abscess, were diagnosed when there were signs of peritonitis, increased white blood cell count, and positive drainage-fluid culture or were confirmed by CT scan and puncture drainage. Wound infection was diagnosed according to the guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[18]. Pneumonia diagnosis required clinical symptoms and radiographic evidence, such as X-ray or CT. In accordance with the Clavien-Dindo classification system, the complications were classified into five grades, and we further stratified the patients into the mild (I-II), moderate (III) and severe groups (IV-V) according to the severity of the symptoms[19]. Mortality was defined as death during the perioperative period or death from surgery-related complications within 1 mo after discharge.

SPSS 18.0 software (Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD or median values and percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t-tests for numerical variables. The risk factors were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In the study, 153 consecutive patients underwent EBD (ENBD or ERBD) prior to PD, of whom 102 (67.7%) underwent ENBD and 51 (33.3%) underwent ERBD. All patients were diagnosed by postoperative pathology, including 111 (72.6%) cases of papilla adenocarcinoma, 25 (16.3%) cases of distal cholangiocarcinoma and 17 (11.1%) cases of pancreatic head cancer. All patients presented with severe jaundice, and the levels of TB and ALT at admission were not significantly different between the ENBD and ERBD groups (P = 0.667 and P = 0.241, respectively). There were no differences in age, gender or concomitant diseases (hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, acute pancreatitis and cholangitis) between the two groups (Table 1). The data regarding the EBD procedure showed that the EST and EBD durations were significantly different between the two groups (Table 1). EST was less frequently performed in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group (P = 0.039), and the mean EBD duration in the ENBD group was shorter than that in ERBD group (P = 0.036). The mean length of biliary stricture was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.849). There were no differences in the procedure of PD between the two groups, such as operative time, intraoperative bleeding, blood transfusion, pancreatic texture, and the diameter of the pancreatic duct and common bile duct (Table 1). Finally, the total expenditure, total hospital stay and postoperative hospital stay were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1).

| Variable | ENBD (n = 102) | ERBD (n = 51) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 55.26 ± 9.07 | 56.24 ± 9.65 | 0.542 |

| Gender (Male) | 58 (56.9) | 29 (56.9) | 1.000 |

| Concomitant diseases | |||

| Hypertension | 9 (8.8) | 5 (9.8) | 0.843 |

| Cardiac disease | 16 (15.7) | 6 (11.8) | 0.515 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (21.6) | 13 (25.5) | 0.586 |

| Anemia | 39 (38.2) | 24 (47.1) | 0.296 |

| Hypoproteinemia | 31 (30.4) | 20 (39.2) | 0.275 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 6 (5.9) | 4 (7.8) | 0.732 |

| Acute cholangitis | 7 (6.9) | 7 (13.7) | 0.233 |

| Malignant disease | 0.307 | ||

| Papilla adenocarcinoma | 70 (68.7) | 41(80.4) | |

| Distal cholangiocarcinoma | 19 (18.6) | 6 (11.8) | |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 13 (12.7) | 4 (7.8) | |

| ALT at admission (IU/L) | 189.16 ± 161.52 | 158.41 ± 132.25 | 0.241 |

| TB at admission (µmol/L) | 198.92 ± 85.57 | 205.45 ± 93.69 | 0.667 |

| Data of EBD | |||

| EST | 48 (47.1) | 33 (64.7) | 0.039 |

| Length of biliary stricture (cm) | 1.55 ± 0.84 | 1.58 ± 0.83 | 0.849 |

| EBD duration (d) | 11.05 ± 4.87 | 13.55 ± 7.60 | 0.036 |

| Data of PD | |||

| Operative time (min) | 358.97 ± 84.21 | 375.49 ± 105.66 | 0.334 |

| Intraoperative bleeding (mL) | 475.49 ± 274.47 | 488.04 ± 306.31 | 0.798 |

| Blood transfusion | 45 (44.1) | 21 (41.2) | 0.729 |

| Pancreas texture (soft) | 56 (54.9) | 22 (43.1) | 0.170 |

| Diameter of pancreatic duct (mm) | 3.35 ± 1.29 | 3.48 ± 1.29 | 0.567 |

| Diameter of common bile duct (cm) | 1.73 ± 0.45 | 1.78 ± 0.52 | 0.540 |

| Total hospital stay (d) | 31.85 ± 10.35 | 29.84 ± 10.03 | 0.254 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 18.50 ± 9.50 | 16.80 ± 8.21 | 0.278 |

| Total expenditure (USD) | 10093 ± 3229 | 10100 ± 2779 | 0.988 |

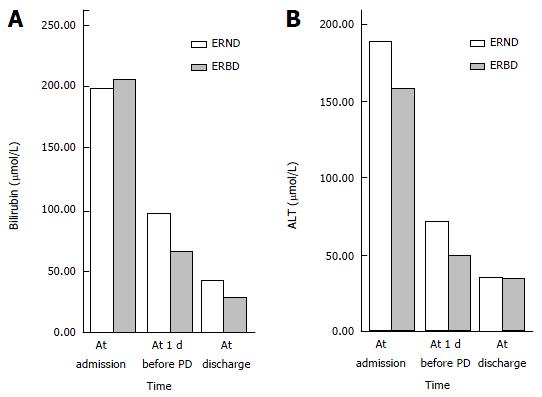

The level of TB at admission was not significantly different between the ENBD and ERBD groups (198.92 ± 85.57 μmol/L and 205.45 ± 93.69 μmol/L, respectively; P = 0.667). After EBD, the level of TB at 1 d before PD was obviously lower in all patients in the two groups, and the extent of the TB decrease in the ENBD group was less than that in the ERBD group (96.45 ± 74.90 μmol/L and 66.01 ± 52.85 μmol/L, respectively; P = 0.004). Similarly, the level of TB decreased more slowly in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group after PD (42.16 ± 42.57 μmol/L and 28.45 ± 25.25 μmol/L, respectively; P = 0.014) (Table 2, Figure 1A).

| Variable | ENBD | ERBD | P value |

| TB at admission (μmol/L) | 198.92 ± 85.57 | 205.45 ± 93.69 | 0.667 |

| ALT at admission (IU/L) | 189.16 ± 161.52 | 158.41 ± 132.25 | 0.241 |

| TB at 1 d before PD (µmol/L) | 96.45 ± 74.90 | 66.01 ± 52.85 | 0.004 |

| ALT at 1 d before PD (IU/L) | 72.63 ± 50.66 | 49.73 ± 28.11 | 0.000 |

| TB at discharge (μmol/L) | 42.16 ± 42.57 | 28.45 ± 25.25 | 0.014 |

| ALT at discharge (IU/L) | 35.49 ± 22.65 | 34.74 ± 34.29 | 0.872 |

The level of ALT at admission was not significantly different between the ENBD and ERBD groups (189.16 ± 161.52 IU/L and 158.41 ± 132.25 IU/L, respectively; P = 0.241). After EBD, the level of ALT at 1 d before PD decreased more slowly in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group (72.63 ± 50.66 IU/L and 49.73 ± 28.11 IU/L, respectively; P = 0.000). However, the level of ALT in the ENBD group decreased as rapidly as that in the ERBD group after PD (35.49 ± 22.65 IU/L and 34.74 ± 34.29 IU/L, respectively; P = 0.872) (Table 2, Figure 1B).

After EBD, the rate of EBD procedure-related cholangitis was significantly lower in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group (7.8% vs 23.5%, P = 0.007); however, there was no difference in EBD dysfunction, EBD procedure-related pancreatitis or other adverse events between the two groups (Table 3).

| Variable | ENBD (n = 102) | ERBD (n = 51) | P value |

| Complications of EBD | |||

| EBD dysfunction | 16 (15.7) | 5 (9.8) | 0.319 |

| Adverse events after EBD | |||

| Pancreatitis | 12 (11.8) | 12 (23.5) | 0.059 |

| Cholangitis | 8 (7.8) | 12 (23.5) | 0.007 |

| Others | 3 (2.9) | 2 (3.9) | 1.000 |

| Complications of PD | |||

| Pancreatic fistula | 34 (33.3) | 21 (41.2) | 0.350 |

| Grade A | 14 (13.7) | 13 (25.5) | |

| Grade B | 16 (15.7) | 7 (13.7) | |

| Grade C | 4 (3.9) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 25 (23.6) | 12 (23.5) | 0.893 |

| Grade A + B | 14(12.8) | 7 (13.7) | |

| Grade C | 11 (10.8) | 5 (9.8) | |

| PPH | 7 (6.9) | 5 (9.8) | 0.523 |

| Grade A + B | 6 (5.9) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Grade C | 1 (1.0) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Biliary fistula | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Deep abdominal infection | 25 (24.5) | 22 (43.1) | 0.019 |

| Wound infection | 17 (16.7) | 10 (19.6) | 0.653 |

| Pulmonary infection | 11 (10.8) | 8 (15.7) | 0.386 |

| Reoperation | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Perioperative death | 5 (4.9) | 3 (5.9) | 1.000 |

| Complication | 60 (58.8) | 34 (66.7) | 0.864 |

| Grade I-II | 39 (38.2) | 21 (41.2) | |

| Grade III | 13 (12.8) | 9 (17.6) | |

| Grade IV-V | 8 (7.8) | 4 (7.9) |

The postoperative complications of PD between the two groups are shown in Table 3. The incidence of deep abdominal infection after PD was significantly lower in the ENBD group than in the ERBD group (24.5% vs 43.1%, P = 0.019), but there was no difference in the incidence of wound infection or pulmonary infection (P = 0.653 and P = 0.386, respectively). The Clavien-Dindo classification of complications was not significantly different between the two groups (58.8% vs 66.7%, P = 0.864). The rate of pancreatic fistula was not significantly different between the ENBD group and the ERBD group (33.3% vs 41.2%, P = 0.350), nor was the difference in the rate of biliary fistula (P = 1.000). The incidence of DGE and PPH as graded by the ISGPS between the two groups was not significantly different (P = 0.893 and P = 0.523, respectively). The rate of reoperation in the ENBD group was not significantly different from that in the ERBD group (P = 1.000). Five (4.9%) patients in the ENBD group and three (5.9%) patients in the ERBD group died during the perioperative period, and there was no significant difference in the perioperative mortality rate (P = 1.000).

The preceding data revealed a significant difference in the incidence of deep abdominal infection between the ENBD and ERBD groups. We performed a univariate analysis to assess the 22 clinical factors of deep abdominal infection between the deep abdominal infection group and the no-deep abdominal infection group. The results showed that gender (male), length of biliary stricture (≥ 1.5 cm), diameter of pancreatic duct (≤ 3 mm), pancreas texture (soft) and EBD method (ERBD) were significant factors. Then, the independent risk factors for deep abdominal infection were identified by multivariate logistic regression analysis. Male gender (OR = 3.92; 95%CI: 1.63-9.47; P = 0.002), soft pancreas texture (OR = 3.60; 95%CI: 1.37-9.49; P = 0.009), length of biliary stricture (≥1.5 cm) (OR = 5.20; 95%CI: 2.23-12.16; P = 0.000) and ERBD method (OR = 4.08; 95%CI: 1.69-9.87; P = 0.002) were independent risk factors for deep abdominal infection after PD (Table 4).

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (≥ 57 yr) | 0.99 (0.48-2.02) | 0.970 | ||

| Gender (Male) | 2.27 (1.09-4.72) | 0.028 | 3.92 (1.63-9.47) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 0.89 (0.27-3.01) | 0.855 | ||

| Cardiac disease | 1.06 (0.40-2.80) | 0.904 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.72 (0.78-3.77) | 0.178 | ||

| Anemia | 0.65 (0.32-1.32) | 0.234 | ||

| Hypoproteinemia | 1.05 (0.51-2.17) | 0.901 | ||

| Acute pancreatitis | 1.55 (0.42-5.77) | 0.513 | ||

| Acute cholangitis | 1.28 (0.41-4.06) | 0.671 | ||

| Malignant disease (pancreatic carcinoma) | 0.60 (0.21-1.67) | 0.325 | ||

| TB at admission (≥ 200 µmol/L) | 0.85 (0.43-1.71) | 0.652 | ||

| ALT at admission (≥ 200 IU/L) | 1.91 (0.87-4.17) | 0.106 | ||

| ERBD method | 2.34 (1.14-4.77) | 0.020 | 4.08 (1.69-9.87) | 0.002 |

| EST | 0.90 (0.45-1.78) | 0.757 | ||

| Length of biliary stricture (≥ 1.5 cm) | 3.89 (1.86-8.14) | 0.000 | 5.20 (2.23-12.16) | 0.000 |

| EBD duration (≥ 12 d) | 0.91 (0.45-1.80) | 0.777 | ||

| Operative time (≥ 380 min) | 0.72 (0.36-1.43) | 0.347 | ||

| Intraoperative bleeding (≥ 600 mL) | 0.66 (0.31-1.40) | 0.278 | ||

| Blood transfusion | 0.85 (0.42-1.71) | 0.652 | ||

| Pancreas texture (soft) | 3.20 (1.53-6.66) | 0.002 | 3.60 (1.37-9.49) | 0.009 |

| Diameter of pancreatic duct (≤ 3 mm) | 2.11 (1.01-4.38) | 0.046 | 1.60 (0.59-4.31) | 0.354 |

| Diameter of common bile duct (> 1.5 cm) | 1.52 (0.76-3.04) | 0.237 | ||

Preoperative EBD was performed in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction with severe jaundice and poor physical condition who were waiting for surgery and preoperative chemotherapy. There is no consensus on whether ENBD or ERBD is preferable prior to PD. In the clinic, surgeons perform ENBD or ERBD primarily based on personal opinion, the degree of bile duct stenosis, equipment conditions, hospital stay duration and economic costs. In the present study, we compared the effects of EBD, the procedure-related complications of EBD, and the postoperative complications of PD between the two groups.

ENBD and ERBD are both effective methods for decreasing the levels of TB and ALT, but ERBD had a better effect on biliary drainage and EBD duration compared to ENBD in the present study due to better tolerance by the patients. However, some studies have shown that the rate of ERBD dysfunction was higher than that of ENBD dysfunction[13,14]. Others have suggested that there was no difference in the rate of EBD dysfunction and the duration from PBD to the time of EBD dysfunction between the two groups[20]. The incidence of EBD dysfunction was associated with pancreatic cancer and the small diameter of the stent[20,21]. In the present study, we found no difference in EBD dysfunction between the ENBD and ERBD groups. This result may be explained by the fact that most of the patients who underwent EBD prior to PD had papilla adenocarcinoma (72.6%), and we typically used the large-diameter plastic stent (> 8 Fr) at our center. In the current study, the self-expandable metal stent seemed to be superior to a plastic stent due to the lower rate of dysfunction[22], but it is not often used because of the high price and lack of compelling evidence.

Procedure-related cholangitis is the most common complication after EBD. Some studies have suggested that because ENBD is an external drainage procedure, it has a lower incidence of preoperative cholangitis than ERBD[14]. However, some researchers have not found significant differences between ENBD and ERBD in the incidence of EBD procedure-related cholangitis, pancreatitis and other complications[20]. In the present study, we showed that the rate of procedure-related cholangitis in the ERBD group was higher than that in the ENBD group. There are several possible explanations for this result. First, EST is more frequently performed in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group. Second, the intestinal contents, including gastrointestinal or external bacteria, run countercurrent to the pancreatic or bile duct past the Odyssey sphincter in ERBD, while the ENBD involves external drainage with less gastrointestinal or bile reflux.

Although PBD has been widely performed at many centers, it was very difficult to identify the optimal EBD duration due to different PBD methods and the different sites of bile duct obstruction. ERBD is more comfortable than ENBD due to the absence of irritation from the nasobiliary catheter to the pharynx and larynx, and it is more easily tolerated by patients. Some studies have shown that the EBD duration in ERBD is longer than that in ENBD[23,24]. Many centers adhere to the 4-6 wk minimum PBD duration, but this protocol may not be universally appropriate because the long PBD duration may increase infectious morbidity and may not be adaptable to all cancers. We showed that a PBD duration < 2 wk was more beneficial for severely jaundiced patients with periampullary cancer than a long duration (> 2 wk); there were fewer drainage-related complications and a shorter hospital stay observed in the cohort that experienced the short PBD duration[25]. In this study, the mean PBD duration was less than 2 wk between the ENBD and ERBD groups, and the PBD duration in the ENBD group was significantly shorter than that in the ERBD group. The reason for this is not clear, but it may be related to the higher incidence of procedure-related complications and the better tolerance by patients in the ERBD group, which might have contributed to a longer PBD duration in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group. Prospective randomized studies are required to identify the optimal drainage duration.

Pancreatic fistula, DGE, biliary fistula, and deep abdominal infection are the most common postoperative complications of PD, especially pancreatic fistula. There are various factors that contribute to the formation of postoperative complications after PD. Some studies have reported that PBD can increase the complications of PD, including pancreatic fistula and infectious complications. Most have shown that the incidence of wound infection was significantly higher in patients with PBD prior to PD than in the patients without PBD treatment before PD due to procedure-related cholangitis and biliary bacterial translocation after PBD[26,27]. Gavazzi et al[27] reported that the overall incidence of the postoperative complications of PD was not significantly different between patients with stented and non-stented treatments. However, the rate of deep incisional surgical site infections was higher in the PBD group than the no-PBD group, and a difference in wound infection was not observed between the two groups; the most common bacterium in the bile or drain fluid was Enterococcus spp. Fujii et al[4] also reported that the cultures of bile or drainage fluid were more often positive in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group, and the incidence of abdominal abscess formation was significantly higher in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group. In the present study, we did not find that the overall complications of PD as graded by the Clavien-Dindo classification were different between the ENBD group and the ERBD group; there was a significant difference in the incidence of deep abdominal infection but not wound infection or pulmonary infection. The evidence shows that the infection complications of PD are important factors affecting the treatment of EBD.

We also found that gender (male), pancreas texture (soft), the length of the biliary stricture (≥ 1.5 cm), and ERBD method were independent risk factors for deep abdominal infection according to univariate and multivariate analyses in the present study. We have several possible explanations for these results. Some researchers have found that male gender is a risk factor for pancreatic fistula[28], and the higher rate of pancreatic fistula may increase infectious complications. Similarly, some studies have suggested that the soft pancreas texture is the most important independent risk for pancreatic fistula after PD[29,30]. The length of the biliary stricture may increase the difficulty of the endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) and prolong the operative time, which can cause procedure-related cholangitis or bacterial translocation. Finally, ERBD was identified as a risk factor for deep abdominal infection; however, prospective randomized studies are required to identify the ERBD as a risk factor for deep abdominal infection. Meanwhile, the results suggest that preoperative EBD via ERBD should be selectively performed in jaundiced patients with high risk factors for infection. Additionally, the ERBD procedure and stent materials should be improved.

There are several limitations to this study. First, due to the retrospective design, the data may not be fully convincing. Second, the study should have included bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity tests. Third, a prospective randomized trial will be required to identify ERBD method and length of the biliary stricture as risk factors for infectious complications after PD.

In conclusion, ENBD and ERBD are both effective biliary drainage methods for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction. ERBD is superior to ENBD in terms of patient tolerance and the effect of biliary drainage, but it increases the risk of EBD procedure-related cholangitis and deep abdominal infection after PD. Therefore, ENBD is the optimal method for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD.

Malignant distal biliary obstruction can lead to obstructive jaundice, and it is caused by periampullary carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, and other malignant diseases. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is recognized as the curative treatment for malignant distal biliary obstruction. Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) can reduce serum bilirubin levels, which may improve the outcomes of surgical treatment. PBD is used at many centers to improve the preoperative state of patients with hyperbilirubinemia or cholangitis. EBD is superior to PTBD for the treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD because PTBD is more invasive and has a higher rate of complication, a higher incidence of catheter tract metastasis, and poorer long-term survival. It remains unknown whether endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) or endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) is more beneficial for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction prior to PD.

The curative treatment for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction is PD. However, despite considerable improvements in surgery and perioperative management, the incidence of complications and postoperative mortality after PD remains high due to severe jaundice and poor preoperative state. This study evaluated the outcomes of preoperative EBD via ENBD and ERBD and the risk factors for deep abdominal infection after PD.

Both ENBD and ERBD are effective methods for biliary drainage in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction and severe jaundice. However, the rate of EBD procedure-related cholangitis was significantly higher in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group, and the incidence of deep abdominal infection after PD was significantly higher in the ERBD group than in the ENBD group. Male gender, soft pancreas texture, the length of the biliary stricture and ERBD method were independent risk factors for deep abdominal infection after PD.

Although ERBD is superior to ENBD in terms of patient tolerance and the effect of biliary drainage, the ERBD method has a high rate of EBD procedure-related complications and is an independent risk factor for deep abdominal infection after PD. Therefore, preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage via ERBD should be selectively performed in jaundiced patients with high risk factors for infection. Additionally, the ERBD procedure and stent materials should be improved.

PD is recognized as the curative treatment for malignant distal biliary obstruction that is caused by periampullary carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma and other malignant diseases. EBD can be performed by ENBD with a nasobiliary catheter or ERBD with a plastic stent.

This study is well written and worthy of publication.

| 1. | Sauvanet A, Boher JM, Paye F, Bachellier P, Sa Cuhna A, Le Treut YP, Adham M, Mabrut JY, Chiche L, Delpero JR; French Association of Surgery. Severe Jaundice Increases Early Severe Morbidity and Decreases Long-Term Survival after Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:380-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Povoski SP, Karpeh MS Jr, Conlon KC, Blumgart LH, Brennan MF. Association of preoperative biliary drainage with postoperative outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:131-142. [PubMed] |

| 3. | van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, Bruno MJ, van der Harst E, Kubben FJ, Gerritsen JJ, Greve JW, Gerhards MF, de Hingh IH. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 717] [Cited by in RCA: 713] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fujii T, Yamada S, Suenaga M, Kanda M, Takami H, Sugimoto H, Nomoto S, Nakao A, Kodera Y. Preoperative internal biliary drainage increases the risk of bile juice infection and pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: a prospective observational study. Pancreas. 2015;44:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barauskas G, Urbonas K, Smailyte G, Pranys D, Pundzius J, Gulbinas A. Preoperative Endoscopic Biliary Drainage May Negatively Impact Survival Following Pancreatoduodenectomy for Ampullary Cancer. Dig Surg. 2016;33:462-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Macías N, Sayagués JM, Esteban C, Iglesias M, González LM, Quiñones-Sampedro J, Gutiérrez ML, Corchete LA, Abad MM, Bengoechea O. Histologic Tumor Grade and Preoperative Bilary Drainage are the Unique Independent Prognostic Factors of Survival in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takahashi Y, Nagino M, Nishio H, Ebata T, Igami T, Nimura Y. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheter tract recurrence in cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1860-1866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Inamdar S, Slattery E, Bhalla R, Sejpal DV, Trindade AJ. Comparison of Adverse Events for Endoscopic vs Percutaneous Biliary Drainage in the Treatment of Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction in an Inpatient National Cohort. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:112-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strom TJ, Klapman JB, Springett GM, Meredith KL, Hoffe SE, Choi J, Hodul P, Malafa MP, Shridhar R. Comparative long-term outcomes of upfront resected pancreatic cancer after preoperative biliary drainage. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3273-3281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Komaya K, Ebata T, Fukami Y, Sakamoto E, Miyake H, Takara D, Wakai K, Nagino M; Nagoya Surgical Oncology Group. Percutaneous biliary drainage is oncologically inferior to endoscopic drainage: a propensity score matching analysis in resectable distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:608-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miura F, Sano K, Wada K, Shibuya M, Ikeda Y, Takahashi K, Kainuma M, Kawamura S, Hayano K, Takada T. Prognostic impact of type of preoperative biliary drainage in patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Uemura K, Murakami Y, Satoi S, Sho M, Motoi F, Kawai M, Matsumoto I, Honda G, Kurata M, Yanagimoto H. Impact of Preoperative Biliary Drainage on Long-Term Survival in Resected Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Multicenter Observational Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S1238-S1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sasahira N, Hamada T, Togawa O, Yamamoto R, Iwai T, Tamada K, Kawaguchi Y, Shimura K, Koike T, Yoshida Y. Multicenter study of endoscopic preoperative biliary drainage for malignant distal biliary obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3793-3802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lin H, Li S, Liu X. The safety and efficacy of nasobiliary drainage versus biliary stenting in malignant biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3553] [Article Influence: 169.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 16. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2451] [Article Influence: 129.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 2065] [Article Influence: 108.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97-132; quiz 133-134; discussion 96. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Sugiyama H, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Nisikawa T, Miyazaki M, Yokosuka O. Preoperative drainage for distal biliary obstruction: endoscopic stenting or nasobiliary drainage? Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hashimoto S, Ito K, Koshida S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Masu K, Iwashita Y, Horaguchi J, Kobayashi G, Noda Y. Risk Factors for Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) Pancreatitis and Stent Dysfunction after Preoperative Biliary Drainage in Patients with Malignant Biliary Stricture. Intern Med. 2016;55:2529-2536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moole H, Jaeger A, Cashman M, Volmar FH, Dhillon S, Bechtold ML, Puli SR. Are self-expandable metal stents superior to plastic stents in palliating malignant distal biliary strictures? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Med J Armed Forces India. 2017;73:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hong SK, Jang JY, Kang MJ, Han IW, Kim SW. Comparison of clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness after various preoperative biliary drainage methods in periampullary cancer with obstructive jaundice. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang X, Liang B, Zhao XQ, Zhang FB, Wang XT, Dong JH. The effects of different preoperative biliary drainage methods on complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Son JH, Kim J, Lee SH, Hwang JH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB, Jang JY, Kim SW, Cho JY. The optimal duration of preoperative biliary drainage for periampullary tumors that cause severe obstructive jaundice. Am J Surg. 2013;206:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ngu W, Jones M, Neal CP, Dennison AR, Metcalfe MS, Garcea G. Preoperative biliary drainage for distal biliary obstruction and post-operative infectious complications. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gavazzi F, Ridolfi C, Capretti G, Angiolini MR, Morelli P, Casari E, Montorsi M, Zerbi A. Role of preoperative biliary stents, bile contamination and antibiotic prophylaxis in surgical site infections after pancreaticoduodenectomy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yamamoto Y, Sakamoto Y, Nara S, Esaki M, Shimada K, Kosuge T. A preoperative predictive scoring system for postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2011;35:2747-2755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gaujoux S, Cortes A, Couvelard A, Noullet S, Clavel L, Rebours V, Lévy P, Sauvanet A, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J. Fatty pancreas and increased body mass index are risk factors of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2010;148:15-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM Jr. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 977] [Article Influence: 69.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Altonbary A, Espinel J, Shih SC S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Li D