Published online May 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3099

Peer-review started: November 21, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Revised: January 12, 2017

Accepted: March 20, 2017

Article in press: March 20, 2017

Published online: May 7, 2017

Processing time: 183 Days and 3.4 Hours

To analyse the impact of octogenarian donors in liver transplantation.

We present a retrospective single-center study, performed between November 1996 and March 2015, that comprises a sample of 153 liver transplants. Recipients were divided into two groups according to liver donor age: recipients of donors ≤ 65 years (group A; n = 102), and recipients of donors ≥ 80 years (group B; n = 51). A comparative analysis between the groups was performed. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean values and SD, and qualitative variables as percentages. Differences in properties between qualitative variables were assessed by χ2 test. Comparison of quantitative variables was made by t-test. Graft and patient survivals were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

One, 3 and 5-year overall patient survival was 87.3%, 84% and 75.2%, respectively, in recipients of younger grafts vs 88.2%, 84.1% and 66.4%, respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.748). One, 3 and 5-year overall graft survival was 84.3%, 83.1% and 74.2%, respectively, in recipients of younger grafts vs 84.3%, 79.4% and 64.2%, respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.524). After excluding the patients with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis (16 in group A and 10 in group B), the 1, 3 and 5-year patient (P = 0.657) and graft (P = 0.419) survivals were practically the same in both groups. Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that overall patient survival was adversely affected by cerebrovascular donor death, hepatocarcinoma, and recipient preoperative bilirubin, and overall graft survival was adversely influenced by cerebrovascular donor death, and recipient preoperative bilirubin.

The standard criteria for utilization of octogenarian liver grafts are: normal gross appearance and consistency, normal or almost normal liver tests, hemodynamic stability with use of < 10 μg/kg per minute of vasopressors before procurement, intensive care unit stay < 3 d, CIT < 9 h, absence of atherosclerosis in the hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries, and no relevant histological alterations in the pre-transplant biopsy, such as fibrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis or macrosteatosis > 30%.

Core tip: An important solution for increasing the donor pool is the use of octogenarian livers after careful selection. We present a comparative study between a group of 102 recipients of donors ≤ 65 years, and 51 recipients of donors ≥ 80 years. One, 3 and 5-year overall patient survival was 87.3%, 84% and 75.2%, respectively, in recipients of younger grafts vs 88.2%, 84.1% and 66.4%, respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.748). One, 3 and 5-year overall graft survival was 84.3%, 83.1% and 74.2%, respectively, in recipients of younger grafts vs 84.3%, 79.4% and 64.2%, respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.524). With good selection octogenarian livers can be safely used.

- Citation: Jiménez-Romero C, Cambra F, Caso O, Manrique A, Calvo J, Marcacuzco A, Rioja P, Lora D, Justo I. Octogenarian liver grafts: Is their use for transplant currently justified? World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(17): 3099-3110

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i17/3099.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3099

Liver transplantation (LT) is the universally accepted procedure for patients who suffer life-threatening chronic and acute liver disease, hepatocarcinoma and several metabolic diseases. The good results obtained over the years with LT have led to an increasing number of candidates on the waiting list, while the number of liver grafts is not enough to attend all patients who need an LT. Consequently, the shortage of liver grafts is associated with waiting list mortality and the main limitation of candidates for LT is having access to a liver graft.

To resolve the graft liver shortage, LT teams have proposed to expand the donor pool using marginal donors or extended-criteria donors, including in this group donors > 60 years, donors with a history of malignancies, with hypernatremia, prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stay, vasoactive drug requirements, steatosis, positive serology for hepatitis C or B virus, livers with a cold ischemia time > 12 h, donation after circulatory death, and grafts from split-liver and living-related donations[1-8]. The donor population in Spain has progressively aged in the last 15 years (12.3% of donors were older than 70 years in 2000 vs 32.3% in 2015). At the same time, cerebrovascular accident as the main cause of liver donor death has also increased from 56.9% in 2000 to 69.6% in 2015[9].

In this situation the best practical measure to increase the number of liver grafts is to increase the donor age[10-19]. However, there is controversy regarding the use of older grafts for LT because several transplant teams reported significantly worse patient and graft survival when they utilized older livers[20-22]. On the other hand, other transplant teams have obtained excellent results in terms of patient and graft survival using liver grafts from donors older than 60[13,17,23], from donors older than 70[10,17,24-29], and even from donors older than 80 years for selected non-hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients[18,19,28,30]. After the first published case of LT using an octogenarian graft[31], we reported a small series of 4 cases with short-term follow-up[32].

Almost nineteen years after our initial experience using octogenarian liver grafts, we present a retrospective case-controlled single-center study comparing the early and long-term results of LT in recipients of livers younger than 65 years old vs recipients of octogenarian livers.

From April 1986 to March 2015, we performed a total of 1778 LTs at our institution (“Doce de Octubre” Complutense University Hospital), including adult and pediatric patients. The first LT using an octogenarian donor was performed in November 1996. From that date to March 2015 we performed 51 LTs with octogenarian liver grafts (case group B). Control group A comprised a sample of 102 adult patients who received a liver graft younger than 65 years at the same period of time. We designed a retrospective case-controlled study comparing a case group B of 51 patients (33.3%) vs a control group A of 102 patients (66.6%). There was a chronological correlation between cases and controls (control LT anterior and posterior to each case; ratio 2:1). For the present study we excluded patients with acute liver failure, HIV+ patients, pediatric, hepato-renal, split liver and living donor transplants, retransplants, and transplants from cardiac-death donor grafts. This study was closed for follow-up at the end of March 2016 with a minimal period of 1 year after LT. All transplant recipients, independently of liver graft age, were periodically followed (every two weeks during first two months, every month during the first year after LT, and thereafter every six months) by the surgeons of the Abdominal Organ Transplantation Unit.

Our general criteria for acceptance of octogenarian liver grafts for LT were good pre-procurement hemodynamic stability (no use or use of low doses of vasopressors), normal or almost normal liver function tests (bilirubin < 2.5 mg/dL, and transaminases < 150 IU/L), short ICU stay (< 4 d), soft consistency, normal histology (absence of hepatitis or fibrosis in liver biopsy), cold ischemia time as short as possible (< 9 h), and preferably no macrosteatosis although levels up to 30% were accepted in the absence of any other additional risk factors. Evidence of microsteatosis was not considered a contraindication. However, the presence of atheromatosis at the bifurcation of the common hepatic artery or the gastroduodenal artery was considered a contraindication for using the octogenarian liver graft. Liver graft preservation injury was classified according to the severity of pericentral or centrilobular necrosis, cytoaggregation and hepatocyte swelling in three categories: mild, moderate and severe. Procurements of all octogenarian and younger liver grafts were performed by aortic and portal vein flush using Celsior or Belzer preservation solutions. All octogenarian liver grafts were procured by our liver transplant team according to Starzl standard technique. When donors showed hemodynamic instability rapid procurement technique was carried out.

We evaluated the following donor variables: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), cause of death, ICU stay, vasopressor use, cardiac arrest, values of liver function tests, such as glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, prothrombin rate, serum levels of sodium, type and rate of steatosis, graft preservation injury, and cold and warm graft ischemia times.

The following pretransplant recipient variables were also recorded: age, sex, BMI, etiology of liver disease, Child-Pugh distribution, D-MELD (Donor Model for End Stage Liver Disease) score, MELD score UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) status, antecedents of diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiopathy or renal disease, pre-LT hematology (hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelets, prothrombin rate), liver function parameter values (total bilirubin, GOT, GPT, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, prothrombin rate), and serum levels of albumin, creatinine and glucose. In the process of organ procurement, pre-transplant liver biopsy was performed on all octogenarian liver grafts and on younger liver grafts when liver abnormalities (steatosis, color, hard consistency, edema, fibrosis, hepatitis) were evident or suspected by macroscopic or biochemical evaluation. All liver biopsies were examined by our pathologist team.

Liver grafts were preserved with Belzer or Celsior solution, and recipient hepatectomy was performed using the vena cava-sparing technique (piggy-back). In these transplant phases we evaluated the following variables: biliary reconstruction techniques, intraoperative transfusions (packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma and platelets), ICU and hospital stays, and base immunosuppression regimens (cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or a combination of tacrolimus and mycophenolate). Serum albumin and liver graft function parameters (total bilirubin, GOT, GPT, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, and prothrombin rate) were evaluated during the first month after LT (serum levels at 1, 3, 7, and 30 d after LT).

We analyzed in both groups post-transplant complications, such as primary graft nonfunction (PNF), rejection (acute, chronic, and steroid-resistant), renal dysfunction (creatinine > 2 mg/dL), biliary, vascular, and infectious complications, reoperations, and retransplantation rate and causes. PNF was defined as GOT > 1500 IU/L and prothrombin rate < 60%, and if the recipient died or required urgent retransplantation within the first 14 d, having excluded extrahepatic causes. Acute rejection episodes were confirmed by histological examination. Causes and rate of mortality and 1, 3, and 5-year patient and graft survival of the groups were analyzed during the follow-up. Patient and graft survival were also comparatively analyzed in a subgroup of patients without HCV cirrhosis who received livers from donors younger than 65 years vs octogenarian donors.

One immunosuppressive regimen comprised cyclosporine, prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and the other consisted of tacrolimus and prednisone. In the presence of renal dysfunction MMF was introduced and calcineurin inhibitors (CNI: cyclosporine or tacrolimus) were reduced. Steroids were usually discontinued between 3 and 12 mo after LT in the cyclosporine regimen, and at 3 mo after LT in the tacrolimus regimen. At the present time we use a tacrolimus-based regimen with decreased doses that includes MMF or mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus or everolimus) in the presence of renal dysfunction, hypertension or diabetes. In the presence of hepatocarcinoma or de novo tumor we reduce the dose of CNI and we add an mTOR inhibitor. Conversion from CNI to MMF monotherapy is performed on long-term follow-up recipients who show severe adverse CNI-related effects but stable liver function.

Acute rejection was initially treated with 1 g of methylprednisolone intravenously for 3 d, and steroid recycling. Steroid-resistant rejection was also treated with antibodies, but currently we usually applied other therapy options such as increasing the dose of tacrolimus and/or adding MMF or mTOR inhibitors.

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean values and SD, and qualitative variables as percentages. Differences in properties between qualitative variables were assessed by χ2 test. Comparison of quantitative variables was made by t-test. Graft and patient survivals were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Comparison of survival curves was performed using the log-rank test. Pre-LT and perioperative variables showing almost or statistically significant differences in the univariate analysis were subsequently investigated in a multivariate analysis using Cox regression procedure to assess the effect of donor age by multiple factors on patient and graft survival. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95%CI were determined by adjusting the donor age. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis of these data was performed with the SAS System for Windows version 9.4.

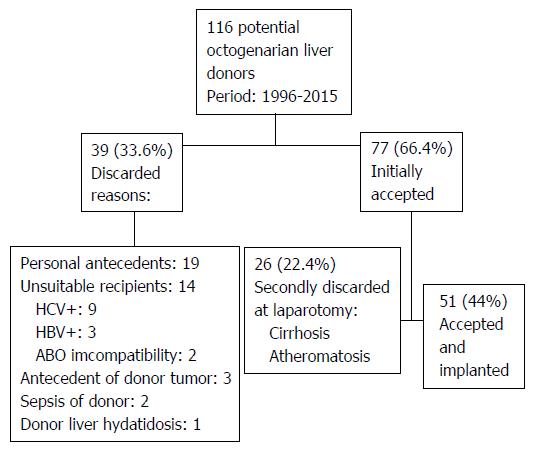

From November 1996 to March 2015 we evaluated 116 potential octogenarian donors for LT, 39 (33.6%) were initially discarded because of donor diseases, absence of suitable recipients, antecedents of donor tumors, donor sepsis, or donor hydatidosis. The remaining 77 (66.4%) donors underwent surgical exploration for liver procurement and 51 (44%) donors were finally accepted for LT, whereas 26 (22.4%) liver grafts were discarded because of the presence of cirrhosis or atheromatosis (Figure 1). In 3 (5.9%) donors the procurement was performed in our center and in 48 (94.1%) donors the procurement was performed by our LT team from other hospitals. Thirty-four (66.6%) octogenarian livers were used between 2010 and 2015.

In comparative analyses between groups A and B, mean donor age was significantly higher in group B (P < 0.001), and females were also significantly more frequent in group B (P < 0.001). BMI was similar in both groups. The octogenarian group showed a significantly higher frequency of cerebrovascular causes of death, but absence of anoxia as cause of death (P = 0.006). In younger donors the ICU stay was significantly longer (P = 0.007) and cardiac arrest was also more frequent (P < 0.001). Younger donors showed significantly higher values of total bilirubin (P = 0.049), GOT (P < 0.001), GPT (P < 0.001), and serum sodium (P = 0.001). The rate and type of graft steatosis (micro and macro) were higher in younger donors, although these differences were not significant. The rate and grade of preservation injury were similar in both donor groups. There were no significant differences in CIT and WIT times between the groups, although in the octogenarian group the mean CIT was one hour longer (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Donors ≤ 65 yr | Donors ≥ 80 yr | P value |

| Group A (n = 102) | Group B (n = 51) | ||

| Donor age (yr) | 46.9 ± 15.0 | 83.5 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male/female) | 62/40 | 13/38 | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index | 26.9 ± 4.5 | 27.2 ± 5.4 | 0.670 |

| > 30 | 26 (25.7) | 15 (29.4) | 0.800 |

| Cause of donor death | 0.006 | ||

| Cerebrovascular | 64 (62.7) | 39 (76.5) | |

| Head trauma | 24 (23.5) | 12 (23.5) | |

| Anoxia | 11 (10.8) | 0 | |

| Other causes | 3 (3.0) | 0 | |

| ICU stay (h) | 67.6 ± 79.6 | 49.9 ± 47.6 | 0.007 |

| Vasopressor use | 78 (76.5) | 33 (64.7) | 0.120 |

| Cardiac arrest | 26 (25.5) | 1 (2.0) | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.77 ± 0.74 | 1.05 ± 1.25 | 0.049 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 63 ± 76 | 30 ± 19 | < 0.001 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 55 ± 69 | 22 ± 18 | < 0.001 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 54 ± 61 | 38 ± 44 | 0.058 |

| Prothrombin rate (%) | 80 ± 20 | 77 ± 23 | 0.460 |

| Sodium (meq/L) | 147 ± 10 | 143 ± 5 | 0.001 |

| Type of steatosis | |||

| Microsteatosis | 26 (25.5) | 11 (21.5) | 0.590 |

| Macrosteatosis | 53 (52.0) | 19 (37.3) | 0.086 |

| Grade of macrosteatosis | |||

| Mild (< 30%) | 45 (44.1) | 19 (37.3) | 0.290 |

| Moderate (30%-60%) | 6 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.077 |

| Severe (> 60%) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Preservation injury | 0.140 | ||

| Mild | 39 (30.4) | 14 (27.5) | |

| Moderate | 30 (26.5) | 13 (25.5) | |

| Severe | 6 (5.9) | 3 (5.8) | |

| CIT (min) | 406 ± 181 | 476 ± 132 | 0.091 |

| WIT (min) | 65 ± 15 | 59 ± 12 | 0.170 |

Mean recipient age was significantly higher in the octogenarian donor group (52.6 ± 11.5 years in group A vs 58.0 ± 8.7 years in group B; P = 0.044). Other recipient variables such as sex distribution, BMI, etiology or indication of LT, Child-Pugh distribution, MELD and D-MELD scores, UNOS status, antecedents of diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiopathy and renal disease, and preoperative laboratory parameter values were similar in both groups, with the exception of a significantly higher value of mean serum glucose in recipients of octogenarian liver grafts (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Donors ≤ 65 years | Donors ≥ 80 years | P value |

| Group A (n = 102) | Group B (n = 51) | ||

| Mean recipient age (yr) | 52.6 ± 11.5 | 58.0 ± 8.7 | 0.044 |

| Sex (male/female) | 71/31 | 42/9 | 0.091 |

| BMI | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 27.3 ± 4.7 | 0.400 |

| Etiology | |||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 47 (46.1) | 29 (56.9) | 0.200 |

| Viral C cirrhosis | 16 (15.7) | 10 (19.6) | 0.540 |

| Viral B cirrhosis | 9 (8.8) | 5 (9.8) | 0.840 |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 24 (23.5) | 18 (36.0) | 0.100 |

| Other | 29 (28.4) | 9 (17.6) | 0.140 |

| Child-Pugh distribution: | 0.310 | ||

| Grade A | 19 (18.7) | 13 (25.5) | |

| Grade B | 40 (39.2) | 24 (47.0) | |

| Grade C | 43 (42.1) | 14 (27.5) | |

| MELD score | 14.9 ± 5.5 | 14.5 ± 6.5 | 0.570 |

| D-MELD score | 706 ± 400 | 1205 ± 526 | 0.220 |

| UNOS status: | 0.160 | ||

| Home | 91 (89.2) | 50 (98.1) | |

| Hospital | 9 (8.8) | 1 (1.9) | |

| ICU | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Antecedents: | |||

| Diabetes | 16 (15.7) | 13 (25.5) | 0.140 |

| High blood pressure | 19 (18.6) | 13 (25.5) | 0.320 |

| Cardiopathy | 20 (19.6) | 12 (23.5) | 0.570 |

| Renal disease | 8 (7.8) | 3 (5.9) | 0.650 |

| Pre-LT laboratory values | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/100 mL) | 11.5 ± 2.120 | 11.8 ± 2.3 | 0.300 |

| Leukocytes/mm3 | 5264 ± 2060 | 5249 ± 2757 | 0.330 |

| Platelets/mm3 | 97376 ± 55284 | 95568 ± 51651 | 0.910 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.5 ± 7.5 | 2.7 ± 3.9 | 0.130 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 70 ± 59 | 74 ± 89 | 0.220 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 45 ± 36 | 51 ± 71 | 0.100 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 129 ± 159 | 100 ± 123 | 0.220 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 233 ± 240 | 169 ± 129 | 0.067 |

| Prothrombin rate (%) | 63 ± 19 | 67 ± 21 | 0.650 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 3.36 ± 0.63 | 3.38 ± 0.64 | 0.570 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.97 ± 0.42 | 1.07 ± 0.58 | 0.660 |

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 115 ± 47 | 143 ± 80 | < 0.001 |

Choledocho-choledochostomy without T-tube was the most common technique used for biliary reconstruction, and was more frequently utilized in recipients of octogenarian donors, although the difference was not statistically significant. Intraoperative transfusions of PRBC, fresh frozen plasma and platelets were not significantly different between the groups. The ICU stay was significantly longer in recipients of octogenarian donors, but the overall hospital stay was not significantly different between the groups. The immunosuppressive regimens (tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or tacrolimus and MMF) were similar in both groups (Table 3).

| Characteristics | Donors ≤ 65 yr | Donors ≥ 80 yr | P value |

| Group A (n = 102) | Group B (n = 51) | ||

| Biliary reconstruction: | 0.090 | ||

| Chol-Chol-without T-tube | 86 (84.3) | 49 (96.1) | |

| Chol-Chol-with T-tube | 12 (11.8) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Hepatico-jejunostomy | 4 (3.9) | 0 | |

| Transfusion | |||

| PRBC (mL) | 3600 ± 4000 | 3320 ± 3748 | 0.390 |

| Plasma (mL) | 2520 ± 1842 | 2288 ± 1706 | 0.960 |

| Platelets (units) | 2.8 ± 3.1 | 2.2 ± 3.0 | 0.510 |

| ICU stay (d) | 5.1 ± 5.1 | 7.3 ± 8.5 | 0.015 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 21.9 ± 17.6 | 24.3 ± 17.6 | 0.520 |

| Immunosuppression: | 0.490 | ||

| Cyclosporine | 15 (14.7) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Tacrolimus | 71 (69.6) | 37 (72.6) | |

| Tacrolimus + MMF | 16 (15.7) | 10 (19.6) |

In recipients of octogenarian donors the mean serum albumin values on the 3rd d (P = 0.009) and the 7th d (P < 0.001) after LT, and the prothrombin rate on the 1st d (P = 0.009), 3rd d (P < 0.001) and 7th d (P = 0.001) after LT were significantly lower in comparison with the recipients of younger donors, but at the 30th d after LT there was not any significant difference of liver function between the groups. The other liver function parameters did not show any significant differences between the groups from the first day to the 30th post-LT day (Table 4).

| Parameters | Donors ≤ 65 yr | Donors ≥ 80 yr | P value |

| Group A (n = 102) | Group B (n = 51) | ||

| GOT (IU/L) | |||

| 1st d | 763 ± 842 | 799 ± 1175 | 0.830 |

| 3rd d | 183 ± 213 | 262 ± 254 | 0.076 |

| 7th d | 67 ± 95 | 78 ± 74 | 0.470 |

| 30th d | 31 ± 27 | 38 ± 43 | 0.260 |

| GPT (IU/L) | |||

| 1st d | 697 ± 682 | 595 ± 525 | 0.370 |

| 3rd d | 537 ± 650 | 484 ± 422 | 0.620 |

| 7th d | 232 ± 198 | 217 ± 180 | 0.650 |

| 30th d | 73 ± 104 | 51 ± 60 | 0.170 |

| GGT (IU/L) | |||

| 1st d | 70 ± 71 | 61 ± 54 | 0.430 |

| 3rd d | 167 ± 149 | 132 ± 102 | 0.100 |

| 7th d | 272 ± 202 | 237 ± 157 | 0.310 |

| 30th d | 226 ± 319 | 182 ± 205 | 0.390 |

| A.Phosphatase (IU/L) | |||

| 1st d | 101 ± 82 | 120 ± 137 | 0.300 |

| 3rd d | 148 ± 102 | 141 ± 101 | 0.690 |

| 7th d | 172 ± 102 | 162 ± 155 | 0.640 |

| 30th d | 262 ± 515 | 201 ± 236 | 0.440 |

| Albumin (g/L) | |||

| 1st d | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 0.280 |

| 3rd d | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 0.009 |

| 7th d | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| 30th d | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 0.550 |

| Prothrombin rate (%) | |||

| 1st d | 64 ± 18 | 56 ± 17 | 0.009 |

| 3rd d | 86 ± 18 | 74 ± 17 | < 0.001 |

| 7th d | 91 ± 16 | 81 ± 18 | 0.001 |

| 30th d | 90 ± 16 | 85 ± 18 | 0.990 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | |||

| 1st d | 3.2 ± 3.3 | 4.0 ± 3.0 | 0.140 |

| 3rd d | 2.4 ± 2.6 | 3.0 ± 2.9 | 0.260 |

| 7th d | 2.7 ± 3.6 | 3.1 ± 38 | 0.450 |

| 30th d | 1.7 ± 4.3 | 1.9 ± 4.4 | 0.780 |

We did not find any significant differences between the groups regarding the rates of post-LT complications and the necessity of a retransplantation procedure. However, although no significant, we observed a higher incidence of acute rejection, and biliary and vascular complications in the group of recipients of younger donors. On the other hand, renal dysfunction was more frequent, but not statistically significant, in recipients of octogenarian livers. Five of these patients needed renal filtration (1 in group A and 4 in group B), but all recovered renal function. The incidence and period of HCV recurrence were similar in both groups. The most frequent causes of retransplantation were technical complications (5 out of 7 cases) (Table 5).

| Complications and mortality | Donors ≤ 65 yr | Donors ≥ 80 yr | P value |

| Group A (n = 102) | Group B (n = 51) | ||

| Primary graft non-function | 1 (0.98) | 1 (1.96) | 0.520 |

| Acute rejection | 33 (32.4) | 10 (19.6) | 0.110 |

| Steroid-resistant rejection | 6 (5.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0.200 |

| Chronic rejection | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0.980 |

| Renal dysfunction | 17 (16.7) | 14 (27.5) | 0.150 |

| Renal filtration | 1 (0.98) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Biliary | 16 (15.7) | 4 (7.8) | 0.380 |

| Vascular | 4 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0.350 |

| Infections | 24 (23.5) | 12 (23.5) | 0.940 |

| Reoperations | 8 (7.8) | 4 (7.8) | 0.970 |

| HCV recurrence rate | 64 (62.7) | 34 (66.6) | 0.530 |

| Mean period (days from LT) | 219 ± 119 | 251 ± 313 | 0.830 |

| Retransplant cases | 5 (4.9) | 2 (3.9) | 0.380 |

| Primary non-function | 1 (0.98) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Chronic rejection | 1 (0.98) | 0 | |

| Biliary complications | 2 (1.96) | 0 | |

| Hepatic artery thrombosis | 1 (0.98) | 0 | |

| HCV recurrence | 0 | 1 (1.9) | |

| Overall mortality | 31 (30.4) | 15 (29.4) | 0.900 |

| Causes of mortality | |||

| Cardiovascular | 6 (5.9) | 7 (13.7) | |

| De novo tumors | 8 (7.8) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Viral C recurrence | 3 (2.9) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Infection | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.9) | |

| HCC recurrence | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Chronic rejection | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Primary non-function | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 4 (3.9) | 2 (3.9) |

During the follow-up period we observed the same rate of mortality in both groups (30.4% in recipients of younger donors, and 29.4% in recipients of octogenarian donors; P = 0.90), and the most frequent causes of death were cardiovascular events, de novo tumors, viral C recurrence, infection, HCC recurrence and chronic rejection (Table 5).

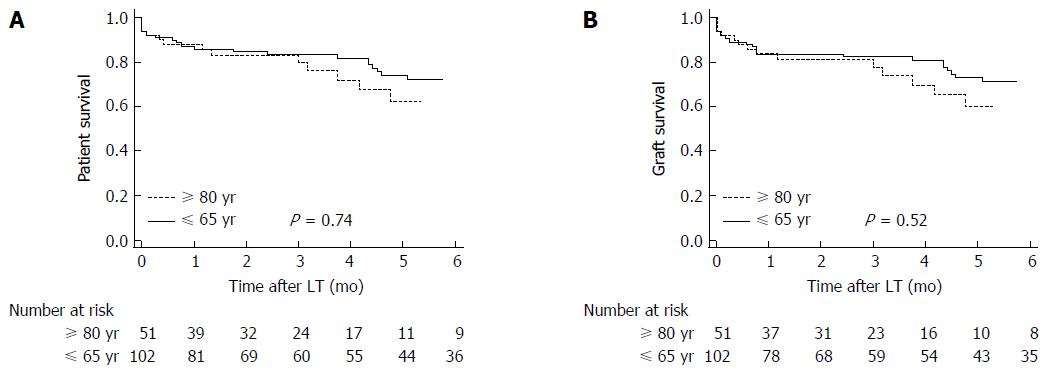

Patient and graft survival were higher, but not statistically significant so, in recipients of donors younger than 65 years. Thus 1, 3 and 5-year overall patient survival was 87.3% (95%CI: 78.7%-92.3%), 84% (95%CI: 74.3%-89.5%) and 75.2% (95%CI: 62.8%-82.3%), respectively, in recipients of younger donors vs 88.2% (95%CI: 75.6%-94.5%), 84.1% (95%CI: 69.4%-91.4%) and 66.4% (95%CI: 42.1%- 77.6%), respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.74) (Figure 2A).

Likewise, 1, 3 and 5-year overall graft survival was 84.3% (95%CI: 75.2%-89.9%), 83.1% (95%CI: 73.5%-88.9%) and 74.2% (95%CI: 63.9%-82.9%), respectively, in recipients of younger donors vs 84.3% (95%CI: 70.6%-71.7%), 79.4% (95%CI: 62.4%-87.8%) and 64.2% (95%CI: 46.3%-79.4%), respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.52) (Figure 2B).

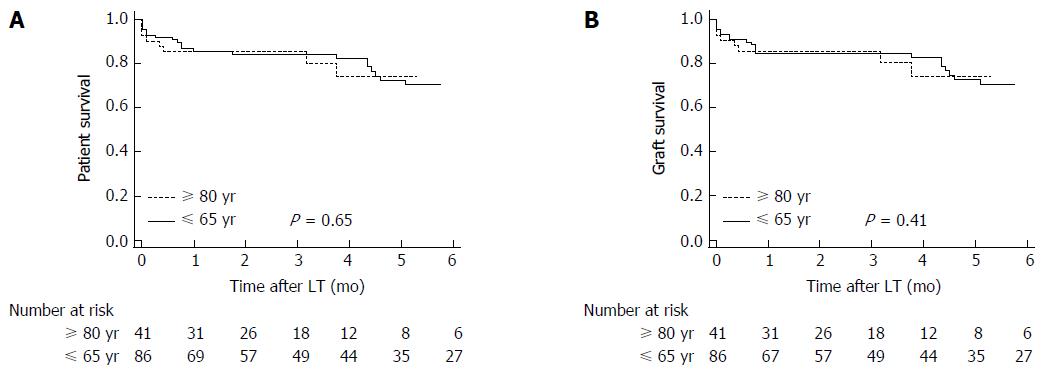

When we excluded the patients with HCV cirrhosis (10 among recipients of octogenarian grafts, and 16 among recipients of donors < 65 years), the 1, 3 and 5-year patient survival was 87.2% (95%CI: 77.7%-92.6%), 84.9% (95%CI: 74.5%-90.6%), and 73.8% (95%CI: 59.7%-81.9%), respectively, in recipients of younger donors vs 85.4% (95%CI: 70.3%-93.1%), 85.4% (95%CI: 70.3%-93.1%) and 76.5% (95%CI: 51.9%-87.2%), respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.65) (Figure 3A). Likewise, the 1, 3 and 5-year graft survival was 84.9% (95%CI: 74.9%-90.8%), 84.9% (95%CI: 74.9%-90.8%), and 73.8% (95%CI: 60.0%-82.1%), respectively, in recipients of younger donors vs 85.4% (95%CI: 70.3%-93.1%), 85.4% (95%CI: 70.3%-93.1%), and 76.5% (95%CI: 60.0%-87.2%), respectively, in recipients of octogenarian grafts (P = 0.41 ) (Figure 3B).

Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that overall patient survival was adversely affected by cerebrovascular donor death, hepatocarcinoma, and recipient preoperative bilirubin. Likewise, overall graft survival was adversely influenced by cerebrovascular donor death, and recipient preoperative bilirubin (Table 6).

| Predictors of patient survival | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Donors ≤ 65 yr vs donors ≥ 80 yr | 0.95 | 0.50-1.79 | 0.872 |

| Cerebrovascular donor death | 2.32 | 1.16-4.65 | 0.017 |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 2.28 | 1.21-4.29 | 0.011 |

| Recipient preoperative bilirubin | 1.05 | 1.02-1.09 | 0.004 |

| Predictors of graft survival | |||

| Donors ≤ 65 yr vs donors ≥ 80 yr | 0.84 | 0.43-1.62 | 0.596 |

| Cerebrovascular donor death | 2.22 | 1.08-4.58 | 0.030 |

| Recipient preoperative bilirubin | 1.04 | 1.01-1.08 | 0.008 |

In the aging process there is an approximately 30% loss of liver volume and hepatic blood flow between the ages of 30 and 100[33,34] that contributes to decreasing the clearance of many drugs[33], and also 37% less protein synthesis in the 69-91 than in the 20-23 year old population[35]. During normal aging there is also a decrease in functional liver mass but liver cells suffer little changes[36]. However, it has been reported that aging has a limited effect on liver functions but more on its response to extrahepatic factors[37], diseases or increased metabolic demands to which the older population may have a reduced capacity of response[35,36].

Since the first reported case of Wall et al[31], several series of octogenarian donors with different periods of follow-up and results have been published[11,12,19,30,32,38,39]. Only two of these seven series report patient and graft survival at 5-years[11,19], an essential time period to demonstrate if the octogenarian grafts can be safely used. The use of liver grafts without age limit is the most important source of grafts to reduce waiting list mortality, especially at the present time in Spain where the number of ideal donors, usually with traffic accidents as the cause of death, has significantly declined.

In this study we used 51 (44%) grafts for LT from 116 potential octogenarian donors, similar to the rate of 45.7% published by other authors[19]. The main reasons for not accepting liver grafts were personal antecedents and disease of donors, unsuitable recipients, or the presence of hepatic artery atheroma or cirrhosis at donor laparotomy. Cerebrovascular diseases range between 73% and 81.7% as the causes of death in several series of octogenarian donors[11,12,19,30], which is similar to 76.5% of our present series.

As was reflected in our first short series[32] liver biopsy during procurement is now widely recommended before accepting the octogenarian liver[19,28,30,39]. Donor age > 65 years has been put forward as the strongest predictor of graft failure[40,41]. It has been published that ICU stays longer than 72 h are also been associated with initial poor graft function or primary nonfunction[42]. In studies comparing octogenarian and younger donors, no significant differences were found regarding ICU stay, BMI > 35 kg/m2, use of epinephrine, prevalence of steatosis, total bilirubin, liver function tests, serum sodium, hypotensive episodes or vasopressor use[12,28]. In the present study we find a significantly longer ICU stay in donors ≤ 65 years, but the mean ICU stay was below 72 h in both groups. The rate of cardiac arrest, mean values of GOT, GPT and serum sodium were significantly higher in donors < 65 years. On the other hand, the mean total bilirubin value was significantly higher in octogenarian donors.

Octogenarian livers with levels of macrosteatosis up to 25%-30% can be accepted for LT[12,19,29,30,32,39], not excluding livers with severe microsteatosis[3,32]. In our series the rate of macrosteatosis was higher, but not statistically significant so in younger donors. CIT has been directly correlated with the development of liver preservation injury with a higher incidence in donors > 60 years[43], but the mean CIT of our octogenarian livers was 70 min longer than that of younger donors and the incidence of preservation injury has been similar in both groups. The reason for the higher CIT in our octogenarian donors is that 94.1% of these donors were procured from other hospitals.

Currently, like in our experience, the most important series of octogenarian livers[12,19,30] agree to implant these grafts in older recipients who show stable clinical conditions but frequently suffer hepatocarcinoma. Our recipients of livers from octogenarian donors were 5.4 years older than recipients of grafts from donors ≤ 65 years (P = 0.044). Likewise, indications with a higher tendency to recurrence, such as alcoholic cirrhosis, viral hepatitis C and B cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma were more frequent in the recipients of octogenarian livers, although not significantly so. The remaining recipient variables were not significantly different between the groups except for a higher value of mean serum glucose in recipients of octogenarian donors. In order to get an acceptable recovery of octogenarian liver function and prevent post-LT complications it is also very important to avoid other recipient risk factors mainly reflected by a high MELD score; in a recent series a MELD score of 24 was considered the limit value[19].

Older livers and especially octogenarian livers are very sensitive to ischemia as has been demonstrated by post-LT cholestatic parameters, but usually these parameters tend to normalize within the first post-LT month[11,12,17]. In our series only serum albumin and prothrombin rates were significantly lower during the first post-LT week in octogenarian liver recipients, but at the end of the first month we did not observe any significant differences between the groups in relation with all liver function tests.

Ghinolfi et al[19] found a higher incidence of biliary complications but a similar rate of vascular complications in recipients of octogenarian livers. As other authors[12], we did not observe a significant difference between the groups regarding the rates of posttransplant complications and retransplants, and rates of acute and chronic rejection, renal dysfunction, biliary and vascular complications, infections and reoperations. According to several series[12,19,28,38] the use of octogenarian livers is not associated with primary graft non-function. In our experience, the most frequent causes of early and late mortality were cardiovascular complications (13.7%) and recurrence of HCV (5.9%). The significantly higher risk for HCV recurrence using older livers has been widely reported, and especially in the octogenarian group where the recurrence rate is logically the highest[11,12,19,30]. Because of the worse outcome associated with the utilization of older donors in recipients with HCV cirrhosis, as was previously reported[28,30,39,44], in the last years we have shifted to implant octogenarian livers more frequently in recipients with hepatocarcinoma and alcoholic cirrhosis, avoiding their use in recipients with HCV cirrhosis. However, the recent introduction of new antiviral drugs for treatment of patients with HCV cirrhosis will probably allow a generalized use of octogenarian donors for this type of recipients.

Among several octogenarian series, 1-year patient survival ranges between 75% and 100%, 3-year patient survival between 40% and 86%[11,12,30,32,38,39], and 5-year patient survival between 78.2% and 86%[11,19]. One-year graft survival varies between 75% and 100%, 3-year graft survival between 61.2% and 81%[11,12,30,32,38,39], and 5-year graft survival between 77.1% and 81%[11,19]. In our study we observed better patient and graft survivals in recipients of livers younger than 65 years, but this was not significant. When we excluded the recipients with HCV cirrhosis from the statistical analysis the results into recipients of octogenarian liver grafts improved, and we found practically the same 1-, 3-, and 5-year patient and graft survival rates in both groups.

In the multivariate analysis, we detected that the independent risk factors for patient and graft survival were cerebrovascular donor death, and pretransplant bilirubin. Moreover, hepatocarcinoma also constitutes an independent risk factor for patient survival. The post-transplant ICU stay was longer in our recipients of octogenarian livers, and this can be attributed to the higher comorbidity (diabetes and cardiovascular disease) and the older age (5.4 years more) of these recipients in comparison with the recipients of younger livers.

In conclusion, careful selection of octogenarian livers is the secret for obtaining results similar to those obtained with younger donors. Thus, the standard criteria for utilization of octogenarian liver grafts are: normal gross appearance and consistency, normal or almost normal liver tests, hemodynamic stability with use of < 10 μg/kg per minute of vasopressors before procurement, ICU stay < 3 d, CIT < 9 h, absence of atherosclerosis in the hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries, and no relevant histological alterations in the pre-transplant biopsy, such as fibrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis or macrosteatosis > 30%. Currently, with the introduction of new anti-HCV drugs the scenario has favourably changed and octogenarian livers could be implanted into HCV positive recipients and thus contribute to increasing the donor pool and improving LT results.

Liver transplantation is the universally accepted procedure for patients who suffer life-threatening chronic and acute liver disease, hepatocarcinoma and several metabolic diseases. The scarcity of liver grafts contributes to increasing waiting mortality, and the main limitation of candidates for liver transplantation is having access to a liver graft. In order to decrease the waiting list mortality, the authors have used liver grafts without age limit, including donors older than 80 years, after a very careful selection.

Authors initiated the use of octogenarian liver grafts in 1996. From that year, several reports have been published, mainly from Mediterranean countries where there is an important necessity of liver grafts. However, at present there is controversy regarding the use of older liver grafts because several transplant teams reported worse patient survival when they utilized older livers. On the other hand, other transplant teams have obtained excellent results in terms of patient survival.

The authors present an almost nineteen year experience using octogenarian liver grafts for transplantation. They are pioneers using octogenarian liver grafts, and this series represent the second most important from a single center. To demonstrate the safely use of these older grafts they have compared octogenarian donors (group B) with donors younger than 65 years (group A). Donor, recipient, intraoperative, and posttransplant variables, and patient and graft survival were compared between the groups. After analysis of these data we summarize several criteria for using octogenarian grafts: normal gross appearance and consistency, normal or almost normal liver tests, hemodynamic stability, ICU stay < 3 d, CIT < 9 h, absence of atherosclerosis in the hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries, and no relevant histological alterations in the pre-transplant biopsy, such as fibrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis or macrosteatosis > 30%.

This study concludes that careful selection of octogenarian livers is the secret for obtaining results similar to those obtained with younger donors. The end benefit will be to decrease the waiting list mortality of patients that suffer hepatocarcinoma and other liver diseases.

Liver transplantation is a replacement of a diseased liver by a healthy liver graft. The native liver is firstly removed and substituted by the liver donor in the same place (orthotopic location). Donor liver grafts < 70 years are more frequently used.

This is a retrospective case-controlled study comparing recipients of donors ≤ 65 years (n = 102) and recipients of donors ≥ 80 years (n = 51). A comparative analysis showed that 1, 3, and 5-year overall patient and graft survivals were not significantly different between the groups. With careful selection the octogenarian liver grafts can be safely used.

| 1. | Strasberg SM, Howard TK, Molmenti EP, Hertl M. Selecting the donor liver: risk factors for poor function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adam R, Sanchez C, Astarcioglu I, Bismuth H. Deleterious effect of extended cold ischemia time on the posttransplant outcome of aged livers. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:1181-1183. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ureña MA, Ruiz-Delgado FC, González EM, Segurola CL, Romero CJ, García IG, González-Pinto I, Gómez Sanz R. Assessing risk of the use of livers with macro and microsteatosis in a liver transplant program. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:3288-3291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Busuttil RW, Tanaka K. The utility of marginal donors in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:651-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | López-Navidad A, Caballero F. Extended criteria for organ acceptance. Strategies for achieving organ safety and for increasing organ pool. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:308-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 6. | Yersiz H, Renz JF, Farmer DG, Hisatake GM, McDiarmid SV, Busuttil RW. One hundred in situ split-liver transplantations: a single-center experience. Ann Surg. 2003;238:496-505; discussion 506-507. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Renz JF, Kin C, Kinkhabwala M, Jan D, Varadarajan R, Goldstein M, Brown R, Emond JC. Utilization of extended donor criteria liver allografts maximizes donor use and patient access to liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2005;242:556-563; discussion 563-565. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bernat JL, D’Alessandro AM, Port FK, Bleck TP, Heard SO, Medina J, Rosenbaum SH, Devita MA, Gaston RS, Merion RM. Report of a National Conference on Donation after cardiac death. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:281-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spanish National Transplant Organization (ONT). Dossier de Actividad en Trasplante Hepático (Dossier in Liver Transplantation Activity). 2015. . |

| 10. | Emre S, Schwartz ME, Altaca G, Sethi P, Fiel MI, Guy SR, Kelly DM, Sebastian A, Fisher A, Eickmeyer D. Safe use of hepatic allografts from donors older than 70 years. Transplantation. 1996;62:62-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cescon M, Grazi GL, Ercolani G, Nardo B, Ravaioli M, Gardini A, Cavallari A. Long-term survival of recipients of liver grafts from donors older than 80 years: is it achievable? Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1174-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nardo B, Masetti M, Urbani L, Caraceni P, Montalti R, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Martinelli G, Bernardi M, Daniele Pinna A. Liver transplantation from donors aged 80 years and over: pushing the limit. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1139-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Anderson CD, Vachharajani N, Doyle M, Lowell JA, Wellen JR, Shenoy S, Lisker-Melman M, Korenblat K, Crippin J, Chapman WC. Advanced donor age alone does not affect patient or graft survival after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:847-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Cescon M, Cucchetti A, Ercolani G, Fiorentino M, Panzini I, Vivarelli M, Ramacciato G, Del Gaudio M. Liver transplantations with donors aged 60 years and above: the low liver damage strategy. Transpl Int. 2009;22:423-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rauchfuss F, Voigt R, Dittmar Y, Heise M, Settmacher U. Liver transplantation utilizing old donor organs: a German single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:175-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Martins PN, Chang S, Mahadevapa B, Martins AB, Sheiner P. Liver grafts from selected older donors do not have significantly more ischaemia reperfusion injury. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:212-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jiménez-Romero C, Clemares-Lama M, Manrique-Municio A, García-Sesma A, Calvo-Pulido J, Moreno-González E. Long-term results using old liver grafts for transplantation: sexagenerian versus liver donors older than 70 years. World J Surg. 2013;37:2211-2221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chedid MF, Rosen CB, Nyberg SL, Heimbach JK. Excellent long-term patient and graft survival are possible with appropriate use of livers from deceased septuagenarian and octogenarian donors. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:852-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ghinolfi D, Marti J, De Simone P, Lai Q, Pezzati D, Coletti L, Tartaglia D, Catalano G, Tincani G, Carrai P. Use of octogenarian donors for liver transplantation: a survival analysis. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2062-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marino IR, Doyle HR, Aldrighetti L, Doria C, McMichael J, Gayowski T, Fung JJ, Tzakis AG, Starzl TE. Effect of donor age and sex on the outcome of liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1995;22:1754-1762. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Busquets J, Xiol X, Figueras J, Jaurrieta E, Torras J, Ramos E, Rafecas A, Fabregat J, Lama C, Ibañez L. The impact of donor age on liver transplantation: influence of donor age on early liver function and on subsequent patient and graft survival. Transplantation. 2001;71:1765-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moore DE, Feurer ID, Speroff T, Gorden DL, Wright JK, Chari RS, Pinson CW. Impact of donor, technical, and recipient risk factors on survival and quality of life after liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2005;140:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rodríguez González F, Jiménez Romero C, Rodríguez Romano D, Loinaz Segurola C, Marqués Medina E, Pérez Saborido B, García García I, Rodríguez Cañete A, Moreno González E. Orthotopic liver transplantation with 100 hepatic allografts from donors over 60 years old. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:233-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Kim DY, Cauduro SP, Bohorquez HE, Ishitani MB, Nyberg SL, Rosen CB. Routine use of livers from deceased donors older than 70: is it justified? Transpl Int. 2005;18:73-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Borchert DH, Glanemann M, Mogl M, Langrehr J, Neuhaus P. Adult liver transplantation using liver grafts from donors over 70 years of age. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1186-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gastaca M, Valdivieso A, Pijoan J, Errazti G, Hernandez M, Gonzalez J, Fernandez J, Matarranz A, Montejo M, Ventoso A. Donors older than 70 years in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3851-3854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Segev DL, Maley WR, Simpkins CE, Locke JE, Nguyen GC, Montgomery RA, Thuluvath PJ. Minimizing risk associated with elderly liver donors by matching to preferred recipients. Hepatology. 2007;46:1907-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cescon M, Grazi GL, Cucchetti A, Ravaioli M, Ercolani G, Vivarelli M, D’Errico A, Del Gaudio M, Pinna AD. Improving the outcome of liver transplantation with very old donors with updated selection and management criteria. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:672-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Darius T, Monbaliu D, Jochmans I, Meurisse N, Desschans B, Coosemans W, Komuta M, Roskams T, Cassiman D, van der Merwe S. Septuagenarian and octogenarian donors provide excellent liver grafts for transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2861-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Singhal A, Sezginsoy B, Ghuloom AE, Hutchinson IV, Cho YW, Jabbour N. Orthotopic liver transplant using allografts from geriatric population in the United States: is there any age limit? Exp Clin Transplant. 2010;8:196-201. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Wall W, Grant D, Roy A, Asfar S, Block M. Elderly liver donor. Lancet. 1993;341:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jiménez Romero C, Moreno González E, Colina Ruíz F, Palma Carazo F, Loinaz Segurola C, Rodríguez González F, González Pinto I, García García I, Rodríguez Romano D, Moreno Sanz C. Use of octogenarian livers safely expands the donor pool. Transplantation. 1999;68:572-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wynne HA, Cope LH, Mutch E, Rawlins MD, Woodhouse KW, James OF. The effect of age upon liver volume and apparent liver blood flow in healthy man. Hepatology. 1989;9:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Regev A, Schiff ER. Liver disease in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:547-563, x-xi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | James OF. Gastrointestinal and liver function of old age. Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;12:671-691. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Wynne HA, James OF. The ageing liver. Age Ageing. 1990;19:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Popper H. Coming of age. Hepatology. 1985;5:1224-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zapletal Ch, Faust D, Wullstein C, Woeste G, Caspary WF, Golling M, Bechstein WO. Does the liver ever age? Results of liver transplantation with donors above 80 years of age. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1182-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Petridis I, Gruttadauria S, Nadalin S, Viganò J, di Francesco F, Pietrosi G, Fili’ D, Montalbano M, D’Antoni A, Volpes R. Liver transplantation using donors older than 80 years: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1976-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Markmann JF, Markmann JW, Markmann DA, Bacquerizo A, Singer J, Holt CD, Gornbein J, Yersiz H, Morrissey M, Lerner SM. Preoperative factors associated with outcome and their impact on resource use in 1148 consecutive primary liver transplants. Transplantation. 2001;72:1113-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, DebRoy MA, Greenstein SM, Merion RM. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:783-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1435] [Cited by in RCA: 1526] [Article Influence: 76.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Greig PD, Forster J, Superina RA, Strasberg SM, Mohamed M, Blendis LM, Taylor BR, Levy GA, Langer B. Donor-specific factors predict graft function following liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:2072-2073. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Briceño J, Marchal T, Padillo J, Solórzano G, Pera C. Influence of marginal donors on liver preservation injury. Transplantation. 2002;74:522-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Jiménez-Romero C, Caso Maestro O, Cambra Molero F, Justo Alonso I, Alegre Torrado C, Manrique Municio A, Calvo Pulido J, Loinaz Segurola C, Moreno González E. Using old liver grafts for liver transplantation: where are the limits? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10691-10702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: De Carlis R, Diaz G, Zhang SJ S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF