Published online Jan 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.178

Peer-review started: August 9, 2016

First decision: September 6, 2016

Revised: September 21, 2016

Accepted: October 19, 2016

Article in press: October 19, 2016

Published online: January 7, 2017

Processing time: 149 Days and 11.4 Hours

Biliary stenosis is a common complication after liver transplantation, and has an incidence rate ranging from 4.7% to 12.5% based on our previous study. Three types of biliary stenosis (anastomotic stenosis, non-anastomotic peripheral stenosis and non-anastomotic central hilar stenosis) have been identified. We report the outcome of two patients with anastomotic stricture after liver transplantation who underwent successful cutting balloon treatment. Case 1 was a 40-year-old male transplanted due to subacute fulminant hepatitis C. Case 2 was a 57-year-old male transplanted due to hepatitis B virus-related end-stage cirrhosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Both patients had similar clinical scenarios: refractory anastomotic stenosis after orthotopic liver transplantation and failure of balloon dilation of the common bile duct to alleviate biliary stricture.

Core tip: Biliary stenosis is the relatively common complication after liver transplantation. Our case report represents one of few documenting evidence of the cutting balloon treatment as a safe and effective procedure in refractory anastomotic stenosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. The cutting balloon treatment could be an alternative therapy to the endoscopic application or the surgical application.

- Citation: Ding F, Tang H, Xu C, Jiang ZB, Yi SH, Li H, Jiang N, Chen WJ, Yang Q, Yang Y, Chen GH. Cutting balloon treatment of anastomotic biliary stenosis after liver transplantation: Report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(1): 178-184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i1/178.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.178

Cutting balloon is an angioplasty device, which appropriately combines microsurgical incision with mechanical dilation. The system was invented by Barath et al[1] and was initially used in percutaneous coronary interventions. Compared with traditional balloon dilation technology, cutting balloon can effectively incise the vascular wall with concentrated and low-dilated pressure.

Cutting balloon technology plays an important role in complex coronary artery lesions[2], but is rarely reported in the field of biliary stenosis after orthotopic liver transplantation[3,4]. This report summarizes the application of cutting balloon treatment in two cases with anastomotic biliary stenosis after liver transplantation.

Case 1 was a 40-year-old male with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related end-stage cirrhosis associated with portal hypertension. The patient, who weighed 71.5 kg, had undergone splenectomy 5 years previously and had no clinical history of other systemic diseases. Laboratory examinations revealed high levels of hepatobiliary enzymes, coagulation factors and quantitative HCV RNA: aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 123.0 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 64 U/L, albumin (ALB) was 34.1 g/L, total bilirubin (TBILI) was 91.62 μmol/L, direct bilirubin (DBILI) was 36.87 μmol/L, prothrombin time (PT) was 15.1 s, the international normalized ratio of prothrombin time (PT-INR) was 1.25, and HCV RNA was 1.21 × 106 IU/mL. Case 2 was a 57-year-old male with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related end-stage cirrhosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient, who weighed 69.0 kg, was diagnosed with type II diabetes 12 years previously and had not undergone abdominal surgery. Blood examination results were as follows: AST 41.0 U/L, ALT 33 U/L, ALB 39.6 g/L, TBILI 73.7 μmol/L, DBILI 49 μmol/L, PT 19.0 s, PT-INR 1.59, and HBV DNA 270 IU/mL. The clinical characteristics of these two patients are described in Table 1.

| Case No. | Age, yr | Sex | Diagnosis | Child-Pugh scores | MELD scores |

| Case 1 | 40 | Male | Subacute fulminant hepatitis C | 9 | 15 |

| Case 2 | 57 | Male | Hepatitis B virus-related end-stage cirrhosis associated with HCC | 6 | 17 |

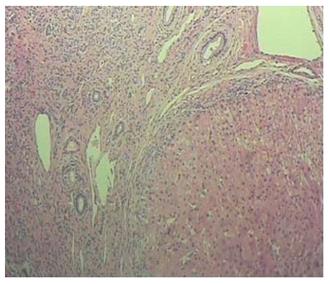

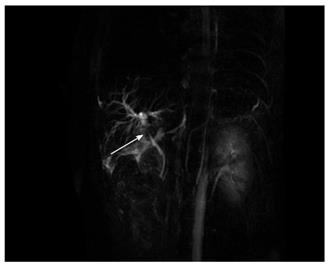

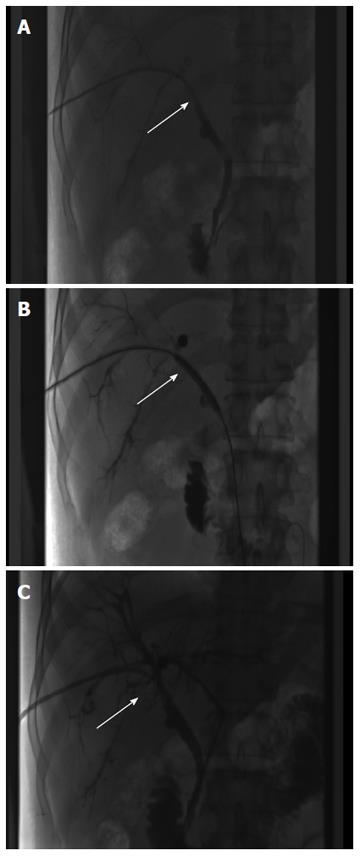

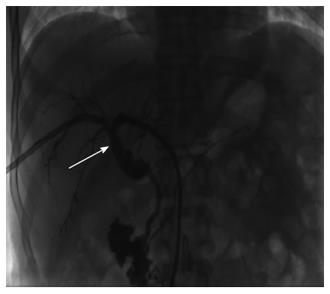

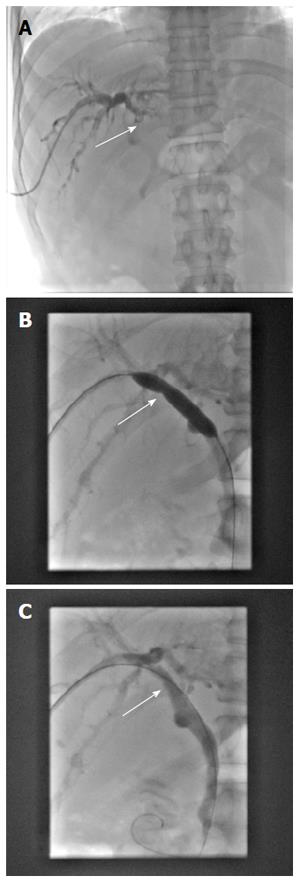

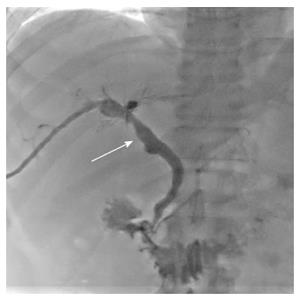

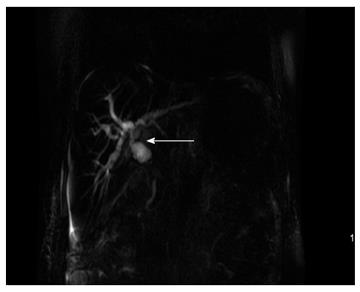

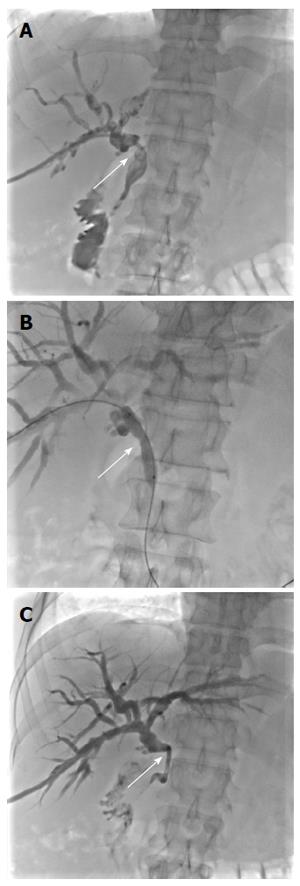

Due to the failure of medical therapy, Case 1 underwent orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) on June 6, 2012 (the liver graft warm ischemia time was 6 min and cold ischemia time was 7 h). Biliary anastomoses were performed by continuous anastomosis with absorbable suture (6-0 PDS suture). Postoperative pathology revealed nodular cirrhosis associated with cholestasis in hepatocytes and capillaries (Figure 1). Immunosuppressive therapy consisting of cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil was administered. Five months later, the patient was readmitted due to xanthochromia and pruritus. Re-examination of hepatic function showed the following results: AST 76 U/L, ALT 52 U/L, TBILI 90.8 μmol/L, DBILI 66.7 μmol/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 179.0 μmol/L and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 315 μmol/L. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed post-OLT anastomotic stenosis of the choledochal duct, intra-hepatic bile duct dilation, and biliary sludge in the common hepatic duct and bilateral hepatic ducts; the patient was diagnosed with transplantation-related ischemic injury involving the biliary tract (Figure 2). On November 16, 2012, percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD) was performed (Figure 3). Minor complications occurred during and after surgery, all of which were resolved following appropriate treatment and nursing. On January 15, 2013, re-examination by cholangiography showed that the anastomotic stenosis was reduced by nearly 20% (Figure 4); thus, we decided to remove the biliary drainage. One year later, the patient was referred to the Clinical Center again because of xanthochromia and pruritus. Clinical laboratory examination results were as follows: AST 129.0 U/L, ALT 42 U/L, TBILI 47.2 μmol/L, DBILI 35 μmol/L, GGT 755 μmol/L, and ALP 4895 μmol/L. On November 22, 2013, based on the clinical history and out-patient examinations, we performed cutting balloon treatment (Figure 5). The key surgical procedures were: the patient was placed in the left position and his abdominal skin was sterilized. The guidewire was then successfully placed in the correct position and the surgeon implanted the cutting balloon into the stenosis site and inflated the balloon (diameter 6 mm, length 4 cm; inflated pressure 6 atm, dilatation time 3 min). The surgeon subsequently consolidated the cutting site with conventional balloon dilatation (diameter 8 mm, length 4 cm). The operation was successful. Complications included abdominal pain, nausea and emesis, which were minor and tolerable. On January 7, 2014, cholangiography indicated that the anastomotic stenosis was resolved (Figure 6). Liver function gradually recovered to physiological level within the 3-year follow-up period.

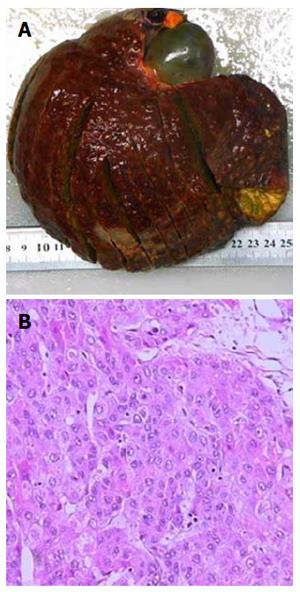

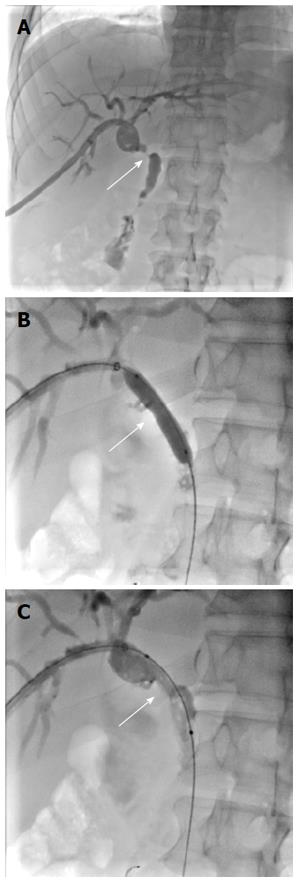

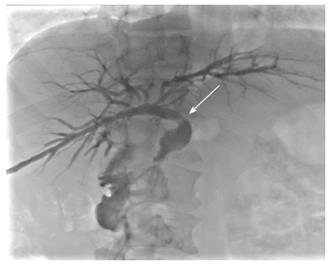

Having met the standard of the “Milan criteria”, OLT was performed in Case 2 on September 14, 2014 (the liver graft warm ischemia time was 0 min and cold ischemia time was 6 h). Biliary anastomosis was performed by continuous anastomosis with absorbable suture (7-0 PDS suture). Postoperative pathology indicated moderately differentiated HCC and nodular cirrhosis pathological changes in peripheral hepatic tissues (Figure 7). Immunosuppressive therapy consisting of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil was administered. Fifteen days after surgery, the patient developed cutaneous or sclera icterus, and emergency examination results were: AST 33 U/L, ALT 41 U/L, TBILI 74.50 μmol/L, DBILI 47.1 μmol/L, GGT 470.0 μmol/L, ALP 537 μmol/L; MRCP revealed severe anastomotic stenosis of the choledochal duct, and severe choledochectasia involving the intrahepatic bile ducts and left-right hepatic bile ducts above the anastomotic stomas. The patient was diagnosed with biliary anastomotic stenosis (Figure 8). On October 4, 2014, PTCD was performed without severe complications (Figure 9). Five months later, cholangiography revealed the presence of anastomotic stenosis, hence cutting balloon treatment was carried out (Figure 10). The surgical procedures were as follows. The patient was placed in the left position and his abdominal skin was sterilized. The guidewire was successfully placed in the correct position. The surgeon implanted the cutting balloon into the stenosis site and inflated the balloon (diameter 5 mm, length 2 cm; inflated pressure 6 atm, dilatation time 3 min). The surgeon subsequently consolidated the cutting site with conventional balloon dilatation (diameter 8 mm, length 4 cm). The surgery was successful. The patient had transient hemorrhage on the first night after surgery. Emergency blood examinations showed no change. Under the standardized management of styptic measures, the prognosis was favorable. On March 10, 2015, cholangiography revealed that the anastomotic stenosis was reduced by 30% (Figure 11), and therefore biliary drainage was immediately removed. The clinical indicators gradually recovered and were maintained within the physiological range during the 10-mo follow-up period.

Postoperative anastomotic biliary stenosis can occur after surgery in the bile ducts of transplanted or non-transplanted liver. The majority of postoperative anastomotic stenosis encountered by the organ transplantation team are most often seen in liver transplant recipients. Three types of biliary stenosis (anastomotic, peripheral, and central) have been reported[5,6]. The causes of biliary stenosis are shown in Table 2. In addition to ischemia and fibrosis, immunological processes and ABO blood type incompatibility are suspected to contribute to biliary stenosis after liver transplantation[7-9].

| Procedure-related factors | Non-procedure-related factors |

| Biliary anastomosis | Chronic pancreatitis |

| Cholecystectomy | Inflammation and infections |

| Ischemic injury | Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| Choledocholithiasis | Radiation therapy |

| Post-endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy | Autoimmune cholangiopathy |

| Trauma | Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction |

Over the past two decades, with the development of technology and endoscopic treatment, the surgical management of biliary stenosis has undergone a rapid decline. Endoscopic treatment has the obvious advantage of high efficiency and a low incidence of procedure-related complications[10]. ERCP was first reported in 1968, and has been used for endoscopic visualization of the ampulla of Vater and minimally invasive cannulation of the pancreatic duct or biliary duct[11]. In 1974, Kawai et al[12] reported their clinical experience of endoscopic electrosurgical sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater to remove gallstones in the common bile duct. This new application in the field of surgical endoscopy was soon accepted as a safe, direct technique for evaluating biliary and pancreatic disease. ERCP has evolved from a diagnostic tool to an almost exclusively therapeutic technique[13]. While ERCP combined with balloon dilation or stent placement is generally effective for biliary stenosis after liver transplantation, uncertainties regarding the optimal therapy remain and can be seen in the variable outcomes described in previous reports of endoscopic treatment[14-17].

The cutting balloon system, which incorporates three or four radially-directed microsurgical blades on the surface of the balloon, is an alternative device that has been used in calcified or rigid lesions[18]. Compared with conventional angioplasty, by creating endovascular micro-incisions during dilatation, the cutting balloon reduces vascular tone, yielding a greater luminal diameter and lower incidence of residual stenosis, which is conducive for lower inflation pressure and a reduced incidence of postoperative complications[19]. This device is particularly suitable for biliary stenosis, which is characterized by a high concentration of elastic and muscle fibers that can generate substantial recoil following balloon inflation[20,21]. We have used cutting balloon treatment in patients who have a high risk of refractory anastomotic stenosis and this treatment has yielded satisfactory results, with no severe postoperative complications, such as bile leakage or catheter-related complications.

In conclusion, cutting balloon treatment for biliary anastomotic stenosis after liver transplantation may be an alternative therapy to endoscopic or surgical treatment, and avoids unnecessary routine stents, directly incising stenosis scars, and has a favorable long-term prognosis.

Two patients were diagnosed with biliary stricture after liver transplantation. Both patients were treated immediately by percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage combined with balloon dilatation. However, cholangiography revealed postoperative restenosis (Case 1 approximately 2 mo later, Case 2 approximately 5 mo later). Both patients underwent cutting balloon treatment with a good prognosis.

Case 1: Initial diagnosis was subacute fulminant hepatitis C complicated by post-orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) anastomotic stenosis of the choledochal duct. Case 2: Initial diagnosis was hepatitis B virus-related end-stage cirrhosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma, complicated by severe anastomotic stenosis of the choledochal duct.

Biliary infection; hepatic insufficiency; ischemic cholangitis.

Hyperbilirubinemia.

Case 1: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed post-OLT anastomotic stenosis of the choledochal duct (Figure 2). Case 2: MRCP revealed severe anastomotic stenosis of the choledochal duct (Figure 8).

Case 1: Nodular cirrhosis associated with hepatocyte and capillary bile cholestasis (Figure 1). Case 2: Moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma and peripheral hepatic tissues revealed nodular cirrhosis pathologic changes (Figure 7).

Cutting balloon treatment with the aim of resolving anastomotic biliary stenosis.

The safety and efficacy of cutting balloon treatment in vascular surgery has been widely reported. Hence, this technology has gradually been used to treat biliary or ureteral stenosis. In the few reports on post-OLT biliary stenosis, although the efficacy requires further clinical evidence, this technology shows huge potential according to the findings in the two cases reported.

Cutting balloon treatment and refractory anastomotic stenosis after OLT.

Cutting balloon treatment may be an alternative therapy to endoscopic or surgical treatment.

The report provides clinical support for the safety and efficacy of cutting balloon treatment used in post-OLT refractory anastomotic stenosis.

| 1. | Barath P, Fishbein MC, Vari S, Forrester JS. Cutting balloon: a novel approach to percutaneous angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1249-1252. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Baber U, Kini AS, Sharma SK. Stenting of complex lesions: an overview. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:485-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Saad WE, Davies MG, Saad NE, Waldman DL, Sahler LG, Lee DE, Kitanosono T, Sasson T, Patel NC. Transhepatic dilation of anastomotic biliary strictures in liver transplant recipients with use of a combined cutting and conventional balloon protocol: technical safety and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:837-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fonio P, Calandri M, Faletti R, Righi D, Cerrina A, Brunati A, Salizzoni M, Gandini G. The role of interventional radiology in the treatment of biliary strictures after paediatric liver transplantation. Radiol Med. 2015;120:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zajko AB, Campbell WL, Bron KM, Schade RR, Koneru B, Van Thiel DH. Diagnostic and interventional radiology in liver transplantation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1988;17:105-143. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ward EM, Kiely MJ, Maus TP, Wiesner RH, Krom RA. Hilar biliary strictures after liver transplantation: cholangiography and percutaneous treatment. Radiology. 1990;177:259-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Friedrich K, Smit M, Brune M, Giese T, Rupp C, Wannhoff A, Kloeters P, Leopold Y, Denk GU, Weiss KH. CD14 is associated with biliary stricture formation. Hepatology. 2016;64:843-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Weeder PD, van Rijn R, Porte RJ. Machine perfusion in liver transplantation as a tool to prevent non-anastomotic biliary strictures: Rationale, current evidence and future directions. J Hepatol. 2015;63:265-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Song GW, Lee SG, Hwang S, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Ha TY, Jung DH, Park GC, Kang SH. Biliary stricture is the only concern in ABO-incompatible adult living donor liver transplantation in the rituximab era. J Hepatol. 2014;61:575-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang JH, Lee I, Choi MG, Han SW. Current diagnosis and treatment of benign biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1593-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | William S McCune, Paul E Shorb, Herbert Moscovitz. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of Vater: a preliminary report. By William S. McCune, Paul E. Shorb, and Herbert Moscovitz, 1968. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:278-280. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Classen M, Demling L. [Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author’s transl)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99:496-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Adler DG, Baron TH, Davila RE, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Qureshi W, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R. ASGE guideline: the role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gürakar A, Wright H, Camci C, Jaboour N. The application of SpyScope® technology in evaluation of pre and post liver transplant biliary problems. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:428-432. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Dawson SL, Mueller PR. Nonoperative management of biliary obstruction. Annu Rev Med. 1985;36:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cotton PB. Critical appraisal of therapeutic endoscopy in biliary tract diseases. Annu Rev Med. 1990;41:211-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee MS, Singh V, Nero TJ, Wilentz JR. Cutting balloon angioplasty. J Invasive Cardiol. 2002;14:552-556. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Okura H, Hayase M, Shimodozono S, Kobayashi T, Sano K, Matsushita T, Kondo T, Kijima M, Nishikawa H, Kurogane H. Mechanisms of acute lumen gain following cutting balloon angioplasty in calcified and noncalcified lesions: an intravascular ultrasound study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;57:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kakani NK, Puckett M, Cooper M, Watkinson A. Percutaneous transhepatic use of a cutting balloon in the treatment of a benign common bile duct stricture. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:462-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Atar E, Bachar GN, Eitan M, Graif F, Neyman H, Belenky A. Peripheral cutting balloon in the management of resistant benign ureteral and biliary strictures: long-term results. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2007;13:39-41. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Hosny K S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Liu WX