Published online Jan 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.127

Peer-review started: August 5, 2016

First decision: September 5, 2016

Revised: September 18, 2016

Accepted: October 19, 2016

Article in press: October 19, 2016

Published online: January 7, 2017

Processing time: 154 Days and 23 Hours

To investigate the effects of depression and anxiety on health-related quality of life (QoL) in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients and those suffering from cardiac (CCP) and noncardiac (NCCP) chest pain in Wuhan, China.

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 358 consecutive patients with GERD were enrolled in Wuhan, China, of which 176 subjects had complaints of chest pain. Those with chest pain underwent coronary angiography and were divided into a CCP group (52 cases) and NCCP group (124 cases). Validated GERD questionnaires were completed, and the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey and Hospital Anxiety/Depression Scale were used for evaluation of QoL and psychological symptoms, respectively.

There were similar ratios and levels of depression and anxiety in GERD with NCCP and CCP. However, the QoL was obviously lower in GERD with CCP than NCCP (48.34 ± 17.68 vs 60.21 ± 20.27, P < 0.01). In the GERD-NCCP group, rather than the GERD-CCP group, the physical and mental QoL were much poorer in subjects with depression and/or anxiety than those without anxiety or depression. Anxiety and depression had strong negative correlations with both physical and mental health in GERD-NCCP (all P < 0.01), but only a weak relationship with mental components of QoL in GERD-CCP.

High levels of anxiety and depression may be more related to the poorer QoL in GERD patients with NCCP than those with CCP. This highlights the importance of evaluation and management of psychological impact for improving QoL in GERD-NCCP patients.

Core tip: Comorbid anxiety and depression and reduced QoL are common problems in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and those suffering from cardiac (CCP) and noncardiac (NCCP) chest pain. In this study, the effects of depression and anxiety on QoL in Chinese GERD subjects with chest pain were assessed. These data demonstrated that high levels of anxiety and depression may have greater negative impact on poorer QoL in GERD patients with NCCP relative to those with CCP. Evaluation and management of the psychological impact could be of great benefit for improving QoL in GERD-NCCP patients.

- Citation: Zhang L, Tu L, Chen J, Song J, Bai T, Xiang XL, Wang RY, Hou XH. Health-related quality of life in gastroesophageal reflux patients with noncardiac chest pain: Emphasis on the role of psychological distress. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(1): 127-134

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i1/127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.127

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common health problem consisting of typical symptoms such as acid regurgitation and heartburn at least once weekly, with a range of prevalence estimates of 2.5%-7.8% in East Asia, 8.8%-25.9% in Europe, and 18.1%-27.8% in North America[1]. GERD is frequently accompanied by chest pain[2], which is the most common atypical symptom of GERD[3]. In fact, gastroesophageal reflux is considered the primary mechanism responsible for chest pain without cardiac origin[4], commonly known as noncardiac chest pain (NCCP). As many as 50% of NCCP patients display abnormal esophageal acid exposure[5]. Typical GERD symptoms, such as heartburn and acid regurgitation, are independently associated with NCCP[6], and antacid therapy is usually effective for patients with NCCP[7,8]. Notably, a considerable portion (31%) of patients with cardiac chest pain (CCP) have comorbid reflux disease, according to GERD questionnaires[9,10]. It is speculated that the high prevalence of reflux symptoms may partly be due to the use of nitrates and Ca2+ antagonists in CCP patients[11,12].

Comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are prevalent in patients with GERD, as well as GERD-related chest pain[13]. Approximately 60% of GERD patients reported worsening of the symptoms during stress[14]. Additionally, there were no significant correlations between the severity of GERD symptoms and the pathophysiological abnormalities detected by 24-h pH monitoring and esophageal manometry, further suggesting the influence of psychiatric factors in symptom perception[14]. It has already been documented that stress and psychological comorbidities may predispose individuals to be more vigilant for physiological sensations, which may result in enhanced response to a painful stimulus or a painful response to an innocuous stimulus and, in some instances, trigger or worsen chest pain of cardiac or esophageal origin[5,11,15].

NCCP patients have also been reported to experience a reduced quality of life (QoL) equal to that experienced by those with CCP[15,16]. Many patients who seek emergency services for chest pain are driven by a fear of myocardial infarction, even if they have been diagnosed as free of heart disease[11]. Psychiatric disorder and fear of pain were independently associated with mental and physical QoL, respectively[15]. However, the impact of depression and anxiety on QoL in GERD patients with NCCP and CCP is far from clear because research in this area is limited, especially in Chinese populations. Furthermore, in many cases, a greater emphasis is placed on the treatment of physical symptoms, and invisible psychological disorders in these subjects is often ignored.

In this observational study, we aimed to assess the differences in the roles of psychological distress on QoL in GERD patients with NCCP (predominantly of esophageal origin) and GERD patients with CCP (predominantly of cardiac origin). These data may provide useful indications for the management of GERD patients with chest pain, as an individualized biopsychosocial model has been proposed[17].

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 358 consecutive patients with GERD from the Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Wuhan, China, were enrolled, of whom 176 had complaints of chest pain. Those with chest pain underwent coronary angiography, and accordingly divided into a CCP group (52 cases) and NCCP group (124 cases). NCCP was defined as patients without stenoses or with stenoses less than 30% in the epicardial coronary artery, and those with obvious stenosis were diagnosed as CCP[18]. All patients provided informed verbal consent and were invited to complete a standardized questionnaire as detailed below. This investigation was approved by the Local Ethical Committee for Clinical Studies in Human, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China.

Demographic characteristics: The self-reported questionnaire containing general characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), education and occupation, as well as living habits, including smoking and alcohol, tea and coffee consumption, was used to collect baseline information.

Rose angina questionnaire: A translated Rose angina questionnaire[16], which had a specificity of 95%, sensitivity of 68%, and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.91, was used to estimate the duration, frequency, severity and characteristics of chest pain[16,19].

Gastroesophageal reflux symptom questionnaire: Clinical presentations and comorbid disorders were evaluated by a previously validated gastro-esophageal reflux symptom questionnaire[5]. On this questionnaire, esophageal and extraesophageal symptoms related to GERD were assessed. The frequency and severity of symptoms were graded on a 5-point Likert scale as previously described[11,16,20]. GERD was diagnosed on the basis of characteristic symptoms, such as heartburn and regurgitation, according to the Montreal standard[21]. A 7-item locally validated GERD questionnaire was used for the diagnosis of GERD, and a cut-off of 12 was recommended for a specificity of 84% and a sensitivity of 82%[18,22].

Hospital anxiety/depression scale: Depressive and anxious symptoms were assessed using a Chinese version of Hospital Anxiety/Depression Scale, which has robust psychometric properties and is brief and easy to administer[23]. The hospital anxiety/depression scale (HADS) consists of 14 items divided into two 21-point subscales for anxiety and depression, and a score of ≥ 8 was considered to be abnormal for either anxiety or depression[5,16].

36-item Short-Form Health Survey: The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is an extensively used generic questionnaire for assessing health related QoL[24], which contained 8 dimensions [bodily pain (BP), physical function (PF), general health (GH), role-physical (RP), role-emotional (RE), mental health (MH), social functioning (SF) and vitality (VT)] and divides into two dimensions, the first four representing a physical component score (PCS) while the last four constituting a mental component score (MCS)[24]. It has good reliability and validity in the assessment of physical and mental QoL[25]. The score ranges from 0 to 100, and the higher score indicating a better health-related QoL[5,24].

Data entry was performed using EpiData 3.1, and SPSS 18.0 was used for statistical analysis. Comparisons of continuous variables were conducted by one-way analysis of variance or non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, followed by the least significant difference test or Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons, when required. Frequency variables were analyzed using chi-square tests. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Spearman correlation analysis was used to identify correlations between psychological disorders and QoL in this study. Multiple regression analysis was further performed to investigate the independent factors impact on the QoL.

Subjects with GERD-NCCP and GERD-CCP were significantly, but not substantially, older than those with GERD without chest pain (51.6 ± 11.4 and 61.13 ± 13.66 vs 46.2 ± 11.5, P = 0.001). Compared with GERD-NCCP patients, GERD-CCP were significantly older (61.13 ± 13.66 vs 51.59 ± 11.44, P = 0.000). However, there was no apparent difference in gender, BMI, and living habits, including smoking and alcohol intake, between these two groups (Table 1).

| GERD without CP | GERD with NCCP | GERD with CCP | |

| (n = 182) | (n = 124) | (n = 52) | |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 46.16 ± 11.51 | 51.59 ± 11.44b | 61.13 ± 13.66bd |

| Sex (male/female) | 104/78 (1.33:1) | 78/46 (1.70:1) | 36/16 (2.25:1) |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 23.44 ± 4.23 | 22.97 ± 3.19 | 23.26 ± 3.57 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 39 (21.2) | 37 (29.8) | 14 (26.9) |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 48 (26.4) | 26 (21.0) | 12 (23.1) |

GERD scores in patients with GERD, GERD-NCCP and GERD-CCP were similar (15.26 ± 3.79, 15.73 ± 3.54 and 15.00 ± 3.44, respectively, P = 0.428) (Table 2). Compared with GERD-NCCP patients, patients with GERD-CCP reported greater chest pain severity, with a significantly higher proportion having moderate to severe chest pain (78.9% vs 69.2%, P = 0.038). Chest pain was also more frequent in GERD-CCP patients than GERD-NCCP patients, with a higher proportion having chest pain attacks one or more times per week (42.3% vs 23.4%, P = 0.046) (Table 2).

| GERD without CP (n = 182) | GERD with NCCP (n = 124) | GERD with CCP (n = 52) | P value | |

| GERD score (mean ± SD) | 15.26 ± 3.79 | 15.73 ± 3.54 | 15.00 ± 3.44 | 0.428 |

| Chest pain severity, n (%) | - | 120 | 52 | 0.038 |

| Mild | 37 (30.8) | 6 (11.5) | ||

| Moderate | 39 (32.5) | 19 (36.5) | ||

| Severe | 37 (30.8) | 22 (42.4) | ||

| Incapacitating | 7 (5.9) | 5 (9.6) | ||

| Chest pain frequency, n (%) | - | 120 | 52 | 0.046 |

| < once per month | 43 (35.8) | 14 (26.9) | ||

| ≥ once per month | 49 (40.8) | 16 (30.8) | ||

| ≥ once per week | 28 (23.4) | 22 (42.3) |

There was a relatively higher proportion (43.5% and 46.2% vs 26.2%, P = 0.022 and 0.027, respectively) and level (6.86 ± 4.64 and 6.46 ± 4.09 vs 4.72 ± 4.13, P = 0.002 and 0.037, respectively) of anxiety in GERD patients with NCCP and CCP than those without chest pain; however, there was no significant difference in anxiety levels between the NCCP and CCP groups (6.86 ± 4.64 vs 6.46 ± 4.09, P = 0.584). (Table 3) For depression, both proportion and level were higher in GERD-NCCP patients than those with GERD and GERD-CCP, but the differences did not reach statistically significant (Table 3). These data suggested that patients with GERD-NCCP and GERD-CCP had equivalent levels of anxiety and depression.

| GERD without CP (n = 182) | GERD with NCCP (n = 124) | GERD with CCP (n = 52) | |

| HADS Depression, n (%) | 72 (39.6) | 61 (49.2) | 19 (36.5) |

| (mean ± SD) | 6.41 ± 4.76 | 7.00 ± 4.49 | 6.17 ± 4.05 |

| HADS Anxiety, n (%) | 48 (26.4) | 54 (43.5)a | 24 (46.2)a |

| (mean ± SD) | 4.72 ± 4.13 | 6.86 ± 4.64b | 6.35 ± 4.06b |

| HADS Depression and Anxiety, n (%) | 45 (24.7%) | 49 (39.5%)a | 23 (44.3%)a |

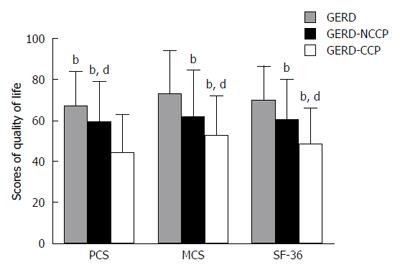

GERD patients with NCCP had lower BP, PF, RE and SF scores compared with those without chest pain; however, patients with GERD-CCP had poorer QoL in the broader aspects, including PF, BP, VT, RP, RE and SF. Particularly, GERD-CCP patients had lower PF, RP, VT and SF scores than those with GERD-NCCP (all P < 0.01) (Table 4). In general, the levels of QoL were, in decreasing order, GERD, GERD-NCCP and then GERD-CCP. Compared with GERD-NCCP subjects, the GERD-CCP group had a significantly lower physical component (44.18 ± 19.11 vs 59.13 ± 20.16, P = 0.000), mental component (52.49 ± 19.92 vs 61.29 ± 23.14, P = 0.018) and total scores (48.34 ± 17.68 vs 60.21 ± 20.27, P = 0.000) (Figure 1).

| GERD without CP | GERD with NCCP | GERD with CCP | |

| (n = 182) | (n = 124) | (n = 52) | |

| Physical function | 97.33 ± 5.33 | 84.55 ± 20.98b | 55.87 ± 26.66bd |

| Role-physical | 54.92 ± 49.75 | 51.23 ± 46.67 | 25.48 ± 36.55bd |

| Bodily pain | 76.52 ± 19.71 | 60.83 ± 22.99b | 54.46 ± 24.66b |

| General health | 38.77 ± 17.69 | 39.92 ± 20.64 | 40.92 ± 21.88 |

| Vitality | 60.62 ± 24.75 | 61.33 ± 22.98 | 49.46 ± 22.66ad |

| Social functioning | 79.30 ± 26.06 | 67.25 ± 25.77a | 53.41 ± 19.55bd |

| Role-emotional | 82.51 ± 37.81 | 53.82 ± 47.42b | 41.89 ± 44.37b |

| Mental health | 68.90 ± 24.46 | 62.77 ± 21.68 | 65.19 ± 19.73 |

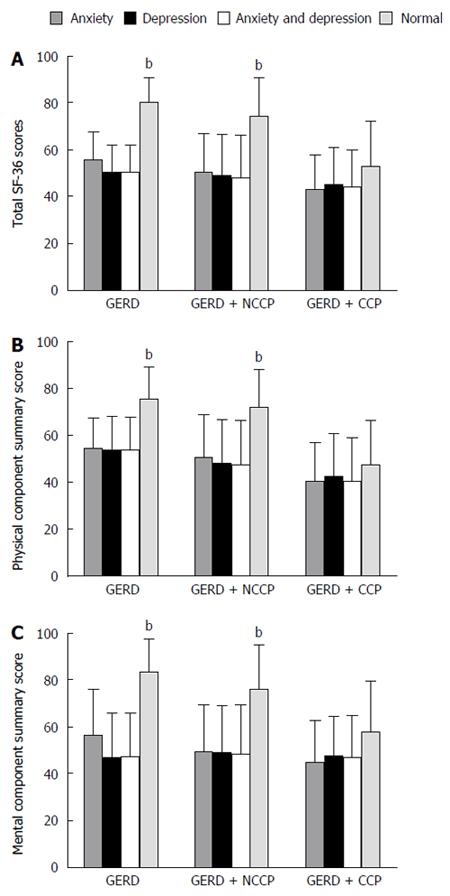

In the GERD and GERD-NCCP groups, the total SF-36 scores (Figure 2A), as well as PCS (Figure 2B) and MCS (Figure 2C), were significantly lower in subjects with depression, anxiety, and both depression and anxiety than those without depression or anxiety (all P< 0.05). However, this difference was not present in the GERD-CCP group (Figure 2).

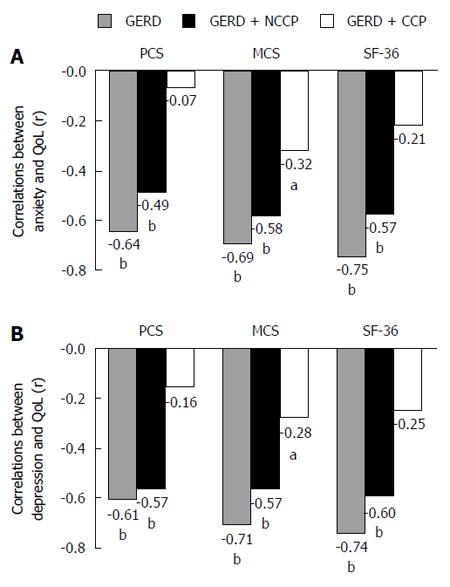

Anxiety had a negative correlation with PCS, MCS and total SF-36 score in GERD (r = -0.64, -0.69 and -0.75, respectively; all P < 0.01) and GERD-NCCP (r = -0.49, -0.58 and -0.57, respectively; all P < 0.01) patients (Figure 3A). Similarly, depression was also negatively correlated with PCS, MCS and total QoL score in GERD (r = -0.61, -0.71 and -0.74, respectively; all P < 0.01) and GERD-NCCP (r = -0.57, -0.57 and -0.60, respectively; all P < 0.01) patients. (Figure 3B) However, anxiety had only a weak negative relation with MCS (r = -0.32, P < 0.05) in GERD-CCP patients, as did depression (r = -0.28, P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

The results of multiple analysis showed that anxiety, depression, GERD and chest pain were independent factors influencing the QoL of GERD patients with CCP and NCCP (the coefficient of determination reaches 0.675 and 0.682, respectively) (Table 5). In GERD patients with NCCP, the influence of anxiety (β = -0.313, P = 0.003) and depression (β = -0.299, P = 0.005) on the QoL were higher than chest pain (β = -0.170, P = 0.017) and GERD (β = -0.153, P = 0.023). On the contrary, the effects of chest pain (β = -0.422, P = 0.001) and GERD (β = -0.236, P = 0.043) on the QoL were dominant factors in GERD patients with CCP.

In this study, the influences of anxiety and depression on health-related QoL of GERD patients with CCP and NCCP were assessed. These data demonstrated that high levels of depression and anxiety, and impaired QoL were prevalent in GERD patients with CCP and NCCP. Importantly, anxiety and depression may contribute differently to the QoL status in GERD patients with NCCP and with CCP.

Impairments of health-related QoL in patients with GERD, as well as those with NCCP and CCP, have been reported previously[18,26-28]. We demonstrated that GERD patients with chest pain had much poorer mental and physical QoL scores than those without chest pain. This difference may be partly because chest pain may be an alarm signal for fatal illness, which may contribute to high levels of psychological burden[3,5], and exacerbate the problem; however, it has been reported that the decreased QoL in patients with NCCP was equivalent to that in those suffering from CCP[29]. In this study, GERD-CCP patients displayed a much poorer QoL (both mental and physical) in comparison with GERD-NCCP ones. This suggests that the functional activity of GERD patients with CCP, which is usually accompanied by a more serious and potentially fatal chest pain, was more likely to be influenced by true heart trouble.

Physical symptoms, particularly chest pain, may also have a negative influence on mental status. There was a relatively higher proportion and level of psychiatric distress, and particularly anxiety symptoms, in GERD patients with NCCP or CCP relative to those without chest pain. In fact, depression and anxiety are two of the most common psychological symptoms related to GERD[26]. The effect of psychosocial factors on the pathogenesis of NCCP is also widely accepted[5,9,13]. These psychological and emotional factors may affect how patients perceive their symptoms[14]. This may partially explain why even slight physiologic stimuli can be interpreted as major symptoms by patients and significantly affect QoL, resulting in dissatisfaction with conventional treatment[14,30]. However, there was no difference in the levels of depression and anxiety between GERD-CCP and GERD-NCCP patients. Despite their lack of cardiac complications, NCCP patients had equivalent psychiatric morbidity, functional impairment, and medical utilization when compared to patients with CCP[31].

This study focused on the role of psychological distress on lower QoL in GERD patients with NCCP and CCP. This action may be different between two groups: (1) in the GERD-NCCP group, but not the GERD-CCP group, physical and mental QoL were much lower in subjects with depression and/or anxiety than those with normal mental status; (2) anxiety and depression exhibited strong negative correlations with QoL in GERD-NCCP patients, while both demonstrated a weak correlation only with the mental components of QoL in GERD-CCP patients; and (3) the independent influence of anxiety and depression on the QoL were stronger than chest pain in GERD-NCCP patients, while chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux were dominant factors in those with CCP. This further suggests that psychological distress plays a more important role in the determination of QoL in GERD patients with NCCP than those with CCP.

Physiological symptoms and psychological distress are two important factors with the potential to substantially affect QoL. As described above, there was a much poorer QoL in GERD-CCP than GERD-NCCP patients, but the levels of anxiety and depression between these two groups were analogous. This may be due to the fact that chest pain and associated symptoms of cardiac origin, rather than anxiety and depression, were stronger factors determining the QoL in CCP patients. On the contrary, relative to subjects with actual cardiac disorders, NCCP patients may experience more cardiac sensations, behavior restriction and illness vigilance[31-33]. In GERD-NCCP subjects, psychiatric distress, which is idiopathic or due to a long-term mental burden of disease, may play a greater important role in determining QoL. Thus, psychological and cognitive intervention may be of great benefit for QoL improvement in the condition of GERD with NCCP.

In conclusion, anxiety and depression, relative to physical illness, may play significant roles in determining the QoL of GERD patients with NCCP. However, in those with GERD-CCP, cardiac chest pain may play a more dominant role in QoL, even with high levels of comorbid depression and anxiety. Therefore, in addition to excluding the cardiac lesion and dealing with the organic illness, we should highlight the importance of the identification and management of psychological impact in improving QoL in GERD-NCCP patients. Moreover, because patients in this study were predominately treated in a comprehensive medical center in Central China, conditions may be different to those visiting a primary physician. It should be more reasonable if a multi-center and widely covered survey could be conducted.

Noncardiac chest pain (NCCP) is the most common atypical symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Notably, a considerable portion of patients with cardiac chest pain (CCP) also have comorbid reflux disease. Comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression, and impaired quality of life (QoL) are prevalent in GERD patients, as well as GERD-related chest pain. However, the impact of psychological factors on QoL in GERD patients with NCCP and CCP is far from clear because research in this area is limited, especially in Chinese populations. In this observational study, we aimed to assess the differences in the roles of psychological distress on QoL in GERD patients with NCCP and those with CCP.

The cause of impaired QoL in GERD and NCCP patients is complicated and multifactorial; besides the physiological dysfunction, psychological factors may not be ignored. Although proton pump inhibitors are now the dominant treatment for GERD and GERD with NCCP, it is not always effective. Interventions pointed at psychological disorders may be of great benefit on improving the QoL of these subjects. So, it is necessary to evaluate the roles of psychological factors on QoL.

This study demonstrated that high levels of depression/anxiety and impaired QoL were prevalent in GERD patients with CCP and NCCP. Importantly, anxiety and depression, relative to physical illness, may play a more significant role in determining the QoL in GERD patients with NCCP. However, in those with GERD-CCP, cardiac chest pain may play a more dominant role in QoL, even with high levels of comorbid anxiety and depression. It further confirmed the important role of psychological factors in QoL decreasing in NCCP patients.

In many cases, a greater emphasis is placed on the treatment of physical symptoms, and invisible psychological disorders in these subjects are often ignored. This study may help clinicians to pay more attention to the importance of identification and management of psychological impact in improving QoL in GERD-NCCP patients.

NCCP: Recurrent episodes of angina-like retrosternal chest pain in patients without cardiac origin. CCP: Retrosternal angina precipitated by exertion and relieved by rest which due to ischaemic heart disease.

The authors report a study on 358 consecutive patients with gastroesophageal reflux with and without chest pain. The data suggest that depression and anxiety is the dominant factor for quality of life while presence or absence of cardiac disease has smaller effects.

| 1. | El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1057] [Cited by in RCA: 1322] [Article Influence: 110.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Wong WM, Fass R. Extraesophageal and atypical manifestations of GERD. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19 Suppl 3:S33-S43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Heidelbaugh JJ, Gill AS, Van Harrison R, Nostrant TT. Atypical presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:483-488. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Oranu AC, Vaezi MF. Noncardiac chest pain: gastroesophageal reflux disease. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Eslick GD, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Non-cardiac chest pain: prevalence, risk factors, impact and consulting--a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1115-1124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Tan VP, Wong BC, Wong WM, Leung WK, Tong D, Yuen MF, Fass R. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Cross-Sectional Study Demonstrating Rising Prevalence in a Chinese Population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:e1-e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Karlaftis A, Karamanolis G, Triantafyllou K, Polymeros D, Gaglia A, Triantafyllou M, Papanikolaou IS, Ladas SD. Clinical characteristics in patients with non-cardiac chest pain could favor gastroesophageal reflux disease diagnosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:314-318. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Coss-Adame E, Erdogan A, Rao SS. Treatment of esophageal (noncardiac) chest pain: an expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1224-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | García-Campayo J, Rosel F, Serrano P, Santed MA, Andrés E, Roca M, Serrano-Blanco A, León Latre M. Different psychological profiles in non-cardiac chest pain and coronary artery disease: a controlled study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:357-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu Y, He S, Chen Y, Xu J, Tang C, Tang Y, Luo G. Acid reflux in patients with coronary artery disease and refractory chest pain. Intern Med. 2013;52:1165-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wong WM, Lai KC, Lau CP, Hu WH, Chen WH, Wong BC, Hui WM, Wong YH, Xia HH, Lam SK. Upper gastrointestinal evaluation of Chinese patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:465-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hughes J, Lockhart J, Joyce A. Do calcium antagonists contribute to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and concomitant noncardiac chest pain? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shapiro M, Simantov R, Yair M, Leitman M, Blatt A, Scapa E, Broide E. Comparison of central and intraesophageal factors between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients and those with GERD-related noncardiac chest pain. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kamolz T, Velanovich V. Psychological and emotional aspects of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:199-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Eslick GD, Talley NJ. Natural history and predictors of outcome for non-cardiac chest pain: a prospective 4-year cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:989-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wong WM, Lam KF, Cheng C, Hui WM, Xia HH, Lai KC, Hu WH, Huang JQ, Lam CL, Chan CK. Population based study of noncardiac chest pain in southern Chinese: prevalence, psychosocial factors and health care utilization. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:707-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Chambers JB, Marks EM, Russell V, Hunter MS. A multidisciplinary, biopsychosocial treatment for non-cardiac chest pain. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:922-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cheung TK, Hou X, Lam KF, Chen J, Wong WM, Cha H, Xia HH, Chan AO, Tong TS, Leung GY. Quality of life and psychological impact in patients with noncardiac chest pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Williams JF, Sontag SJ, Schnell T, Leya J. Non-cardiac chest pain: the long-term natural history and comparison with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2145-2152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mousavi S, Tosi J, Eskandarian R, Zahmatkesh M. Role of clinical presentation in diagnosing reflux-related non-cardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:218-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2520] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Wong WM, Lam KF, Lai KC, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lam CL, Wong NY, Xia HH, Huang JQ, Chan AO. A validated symptoms questionnaire (Chinese GERDQ) for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in the Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1407-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yang Y, Ding R, Hu D, Zhang F, Sheng L. Reliability and validity of a Chinese version of the HADS for screening depression and anxiety in psycho-cardiological outpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hadlandsmyth K, White KS, Krone RJ. Quality of life in patients with non-CAD chest pain: associations to fear of pain and psychiatric disorder severity. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:284-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Thumboo J, Wu Y, Tai ES, Gandek B, Lee J, Ma S, Heng D, Wee HL. Reliability and validity of the English (Singapore) and Chinese (Singapore) versions of the Short-Form 36 version 2 in a multi-ethnic urban Asian population in Singapore. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2501-2508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang XJ, Jiang HM, Hou XH, Song J. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and their effect on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4302-4309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Lee SW, Lien HC, Lee TY, Yang SS, Yeh HJ, Chang CS. Heartburn and regurgitation have different impacts on life quality of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12277-12282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ortiz-Garrido O, Ortiz-Olvera NX, González-Martínez M, Morán-Villota S, Vargas-López G, Dehesa-Violante M, Ruiz-de León A. Clinical assessment and health-related quality of life in patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2015;80:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Remes-Troche JM. The hypersensitive esophagus: pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment options. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:417-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nguyen TM, Eslick GD. Systematic review: the treatment of noncardiac chest pain with antidepressants. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:493-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mourad G, Jaarsma T, Hallert C, Strömberg A. Depressive symptoms and healthcare utilization in patients with noncardiac chest pain compared to patients with ischemic heart disease. Heart Lung. 2012;41:446-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | White KS, Craft JM, Gervino EV. Anxiety and hypervigilance to cardiopulmonary sensations in non-cardiac chest pain patients with and without psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:394-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shelby RA, Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Silva SG, McKee DC, She L, Waters SJ, Varia I, Riordan YB, Knowles VM. Pain catastrophizing in patients with noncardiac chest pain: relationships with pain, anxiety, and disability. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:861-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Moraes JP, Schweiger U S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Wang CH