Published online Dec 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10673

Peer-review started: October 14, 2016

First decision: November 14, 2016

Revised: November 22, 2016

Accepted: November 23, 2016

Article in press: November 28, 2016

Published online: December 28, 2016

Processing time: 74 Days and 1.5 Hours

To analyze the effects of premedication with Pronase for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) examination of the stomach.

This was a prospective, randomized and controlled clinical study. All patients were randomly assigned to either the Pronase group or placebo group. The pretreatment solution was a mixed solution of 20000 U of Pronase and 60 mL sodium bicarbonate solution in the Pronase group, while an equal amount of sodium bicarbonate solution was administered to the placebo group. All operators, image evaluators and experimental recorders in EUS did not participate in the preparation and allocation of pretreatment solution. Two blinded investigators assessed the obscurity scores for the EUS images according to the size of artifacts (including ultrasound images of the gastric cavity and the gastric wall). Differences in imaging quality, the duration of examination and the usage of physiological saline during the examination process between the Pronase group and the control group were compared.

No differences existed in patient demographics between the two groups. For the gastric cavity, the Pronase group had significantly lower mean obscurity scores than the placebo group (1.0476 ± 0.77 vs 1.6129 ± 0.96, respectively, P = 0.000). The mean obscurity scores for the gastric mucosal surface were significantly lower in the Pronase group than the placebo group (1.2063 ± 0.90 vs 1.7581 ± 0.84, respectively, P = 0.001). The average EUS procedure duration for the Pronase group was 11.60 ± 3.32 min, which was significantly shorter than that of the placebo group (13.13 ± 3.81 min, P = 0.007). Less saline was used in the Pronase group than the placebo group, and the difference was significant (417.94 ± 121.38 mL vs 467.42 ± 104.52 mL, respectively, P = 0.016).

The group that had Pronase premedication prior to the EUS examination had clearer images than the placebo group. With Pronase premedication, the examination time was shorter, and the amount of saline used during the EUS examination was less.

Core tip: Previous studies have confirmed that Pronase can improve the quality of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) images. Based on previous findings, this study hypothesized that Pronase could further shorten the duration of examination and reduce the usage of physiological saline during EUS examination through improving the quality of EUS images. Moreover, this study verified this hypothesis. This study found that for EUS examination, preoperative application of Pronase could provide clearer ultrasound images, shorten the duration of EUS examination, and reduce the intraoperative usage of physiological saline.

- Citation: Wang GX, Liu X, Wang S, Ge N, Guo JT, Sun SY. Effects of premedication with Pronase for endoscopic ultrasound of the stomach: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(48): 10673-10679

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i48/10673.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10673

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an important tool to diagnosis benign and malignant diseases of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreaticobiliary system[1-4]. Previous studies demonstrated its superiority in evaluating the staging of early gastric carcinoma and gastric submucosal tumors, as compared with standard diagnostic modalities such as computed tomography, conventional ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging[5-14]. Gastric mucus is one of the most frequent sources of artifacts during an EUS[15,16]. The vague image will influence the EUS procedure and increase the inspection time. Low-quality EUS images could lead to the misdiagnosis of small lesions and misinterpretation of the invasion depth in early gastric cancer[17,18]. To flush the mucosa and eliminate artifacts, more saline would need to be injected into the stomach, which is associated with a more uncomfortable examination and an increased risk of aspiration.

Pronase, separated and extracted from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces griseus[19-21], is a kind of proteolytic enzyme that can disrupt the mucous gel layer on the surface of the stomach[22], and it has been used to prepare digestive and anti-inflammatory enzymes. Fujii et al[23] first found that during chromoendoscopy and conventional endoscopy procedures, premedication with Pronase could improve endoscopic visualization. Over the last 10 years, it has become common practice to provide patients a pretreatment solution containing dimethylpolysiloxane and Pronase before endoscopy. Sakai et al[15] found that pretreatment with Pronase could reduce artifacts during an EUS examination. Han et al[24] also found that premedication with a mixture containing bicarbonate and Pronase seemed to reduce hyperechoic artifacts secondary to the gastric wall and lumen.

Herein, we presumed that decreasing the number of artifacts would shorten the EUS examination, leading to a decrease in the amount of saline solution irrigated during the procedure. To further address this hypothesis, we conducted this study to analyze the effects of Pronase on EUS imaging and EUS duration time, as well as the saline volume irrigated during EUS.

This prospective, randomized and controlled single-center study was conducted at the Endoscopic Center of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University. The eligibility and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. At least 102 patients were needed to acquire 90% statistical power based on a previous study performed by Han et al[24] in 2011. All patients provided written informed consent before the procedure. The Institutional Review Board of China Medical University approved this study based on the Helsinki Declaration. The trial was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-DPD-15006240).

| Eligibility criteria | |

| 1 | Patients who required an EUS examination because of gastric diseases |

| 2 | Patients aged 18-70 yr |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| 1 | Patients with contraindications to endoscopy |

| 2 | Patients allergic to the pharmaceutical ingredients |

| 3 | Patients with gastric bleeding or suspected gastric bleeding |

| 4 | Patients with blood coagulation dysfunction |

| 5 | Patients with severe psychological diseases such as depression, anxiety, hypochondria and hysteria |

| 6 | Patients with severe cardiac dysfunction (NYHA cardiac function classification ≥ class III) |

| 7 | Patients with abnormal hepatic function (serum ALT and AST levels of ≥ 4 times the upper normal limit) |

| 8 | Patients with renal dysfunction (serum Cr level of ≥ 2 times the upper normal limit) |

| 9 | Patients with moderate to severe ventilatory dysfunction |

| 10 | Diabetic patients with unsatisfactory glycemic control |

| 11 | Hypertensive patients with unsatisfactory blood pressure control |

| 12 | Pregnant women or women who are breastfeeding |

The local clinical trials unit performed computerized individual randomization. Included patients were randomly assigned to either the Pronase or placebo group with a computer-generated random allocation sequence. In the placebo group, the premedication solution contained a 1 g sodium bicarbonate solution; in the Pronase group, the premedication solution contained a 1 g sodium bicarbonate solution and 20000 U of Pronase. All the solutions were placed in a paper cup of the same color. In both groups, 60 mL of the premedication solution was administrated about 10-30 min before the EUS examination, as a previous report recommended[25]. The study investigators were not involved in the preparation of the premedication solution. All patients underwent EUS examinations using both radial and linear-array systems. All procedures were carried out by one endosonography.

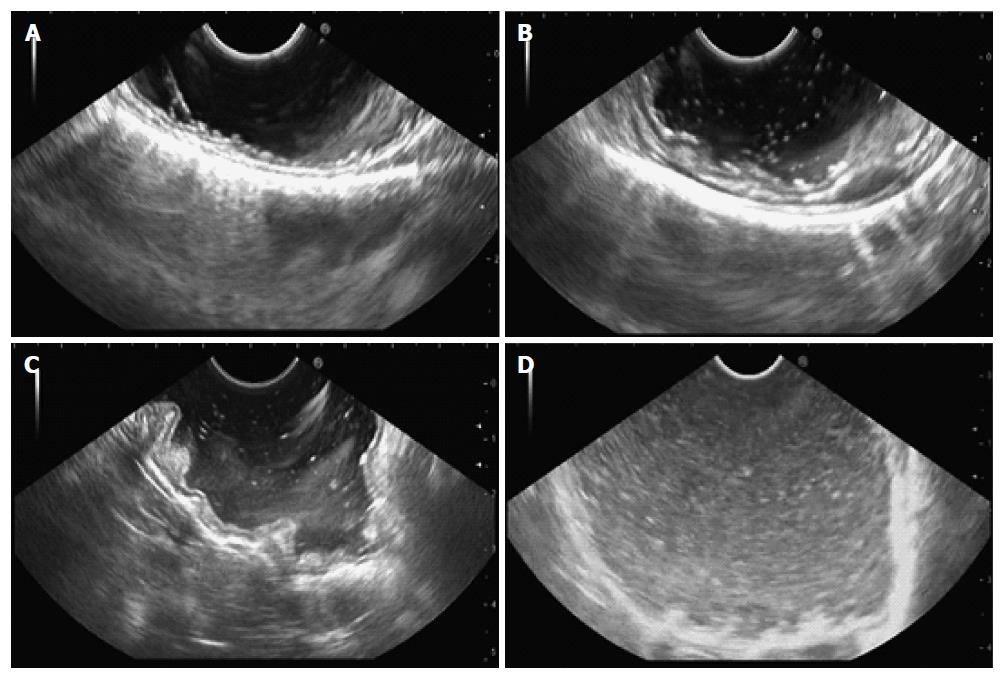

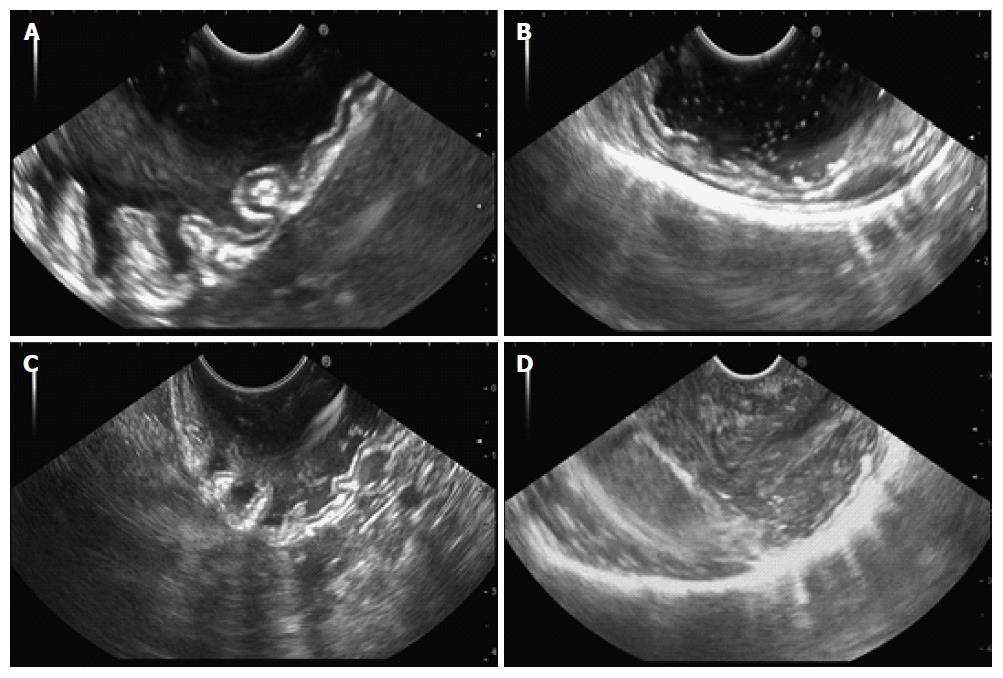

As previously reported[15,24], for EUS imaging, the gastric cavity obscurity grade is scored from 0 to 3 (Figure 1), according to the number of high-echo spots, as shown in Table 2. EUS imaging of the gastric wall surface was similarly scored (Figure 2), as shown in Table 3. All EUS images were assigned to two experienced endoscopists, who scored the images and were blind to the procedure at the time of scoring. We recorded the duration of the EUS procedure for all patients. EUS duration was measured from the time the endoscope was inserted into the mouth to the time the endoscope was withdrawn from the mouth. One investigator recorded the volume of saline solution irrigated during the EUS procedure to determine whether premedication with Pronase decreased the amount of saline used.

| Score | Number of high-echo spots |

| 0 | No or few |

| 1 | Low |

| 2 | Moderate |

| 3 | High |

| Score | Artifacts |

| 0 | Notable, affecting the diagnosis |

| 1 | Moderate |

| 2 | Negligible |

| 3 | None, clear wall interface |

The demographic characteristics were assessed using a Pearson χ2 test or one-way analysis of variance. The obscurity scores for the two groups were assessed using a rank sum test with Mann-Whitney U comparisons and the Student’s t-test. The mean obscurity scores for the gastric cavity and gastric mucosal surface, the EUS procedure duration and the volume of saline were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using the Student’s t-test. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

From May 2015 to July 2015, 125 patients were enrolled in the study and allocated equally to either the Pronase group (63 patients) or placebo group (62 patients). There were no differences in age (P = 0.319), sex (P = 0.611), location (P = 0.532), or EUS methods (P = 0.391) between groups, as shown in Table 4.

| Pronase group | Placebo group | Value | P value | |

| Number of patients | 63 | 62 | ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 55.78 ± 12.37 | 53.47 ± 13.41 | t = 1.001 | 0.319 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 22 | 19 | χ2 = 0.259 | 0.611 |

| Female | 41 | 43 | ||

| Location | ||||

| Fundus | 14 | 9 | χ2 = 1.264 | 0.532 |

| Corpus | 26 | 29 | ||

| Antrum | 23 | 24 | ||

| Methods | ||||

| Radial EUS | 48 | 43 | χ2 = 0.737 | 0.391 |

| Linear-array EUS | 15 | 19 | ||

The obscurity scores for the gastric cavity and gastric mucosal surface were compared between the two groups (Table 5). The Pronase group had significantly lower obscurity scores for the gastric cavity and gastric mucosal surface than the placebo group (P < 0.05).

| Pronase group | Placebo group | Value | P value | |

| Gastric cavity obscurity scores during EUS | ||||

| 3 | 14 | 8 | Z = -3.428 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 35 | 21 | ||

| 1 | 11 | 20 | ||

| 0 | 3 | 13 | ||

| Gastric mucosal surface obscurity scores during EUS | ||||

| 3 | 11 | 7 | Z = -3.861 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 37 | 10 | ||

| 1 | 6 | 36 | ||

| 0 | 9 | 9 | ||

Table 6 compares the mean obscurity scores for the gastric cavity and gastric mucosal surface, and EUS procedure means, as well as the mean volume of saline irrigated during the EUS procedure. As for the gastric cavity, the mean obscurity scores in the Pronase and placebo groups were 1.0476 ± 0.77 and 1.6129 ± 0.96, respectively. Additionally, for the gastric cavity, the Pronase group had significantly lower mean obscurity scores than the placebo group (P = 0.000). As for the gastric mucosal surface, the mean obscurity scores in the Pronase and placebo groups were 1.2063 ± 0.90 and 1.7581 ± 0.84, respectively. Further, for the gastric cavity, the Pronase group had significantly higher mean obscurity scores than the placebo group (P = 0.001).

| Pronase group | Placebo group | Value | P value | |

| Mean gastric cavity obscurity scores | 1.0476 ± 0.77 | 1.6129 ± 0.96 | t = -3.617 | 0.000 |

| Mean gastric mucosal surface obscurity scores | 1.2063 ± 0.90 | 1.7581 ± 0.84 | t = -3.534 | 0.001 |

| Duration of EUS, mean ± SD | 11.60 ± 3.32 | 13.13 ± 3.81 | t = -2.387 | 0.018 |

| Volume of saline, mean ± SD | 417.94 ± 121.38 | 467.42 ± 104.52 | t = -2.441 | 0.016 |

The average EUS procedure time for the Pronase group was 11.60 ± 3.32 min, which was significantly shorter than the placebo group (13.13 ± 3.81 min, P = 0.007). The mean saline volumes were 417.94 ± 121.38 mL and 467.42 ± 104.52 mL in the Pronase group and placebo group, respectively. The amount of saline used for the Pronase group was less than that of the placebo group, and the difference was significant (P = 0.016).

EUS is now increasingly available and plays a significant role in the diagnosis and intervention of gastrointestinal and pancreaticobiliary diseases[1,26-29]. Artifacts secondary to gastric mucus can potentially interfere with visibility during EUS scanning of the stomach. Bubbles and foams may lead to blurred layers and borders and the possible diagnosis of a lesion that does not exist[16,30-32]. Before EUS, premedication played a major role in ensuring satisfactory visualization of the gastric cavity and wall[22,23,33].

Pronase, which can eliminate gastric mucus as a mucolytic enzyme, can further improve diagnosis of gastric diseases using radiographic imaging techniques[34]. A randomized study conducted by Fujii et al[23] demonstrated that premedication with Pronase not only substantially enhanced visibility before and after methylene blue spraying, but also reduced the duration of chromoendoscopy examination. In 2002, Kuo et al[22] also found that premedication with Pronase provided the clearest endoscopic visibility. In 2003, Sakai et al[15] reported the first Pronase trial and suggested that premedication with Pronase reduced artifacts during endoscopic ultrasonography. In 2011, Han et al[24] found that premedication with bicarbonate mixed with Pronase decreased the number of hyperechoic artifacts secondary to the stomach wall and lumen during EUS.

As for the gastric mucosal surface and gastric cavity, we found that the Pronase group had significantly lower obscurity scores than the placebo group. The average time for the EUS examination was significantly shorter for the Pronase group than the placebo group. The amount of saline irrigated was significantly less for the Pronase group than the placebo group. The Pronase premedication solution provided clearer images of the patients according to the endosonographer, which may facilitate EUS examination and shorten the procedure duration. Meanwhile, a clearer image may lead to less saline usage during the EUS examination.

Woo et al[25] found that the administration of Pronase, sodium bicarbonate, and dimethylpolysiloxane 30 min before gastroduodenoscopy helped improve endoscopic visualization remarkably, and the best visibility was achieved with the Pronase administration 10 min to 30 min before the gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure. In this study, we recommended that patients take the premedication solution 10 min to 30 min before the EUS procedure.

In conclusion, for EUS, the group that was administered Pronase premedication had clearer images than the placebo group. With Pronase premedication, the examination time was shorter, and the amount of saline used during the EUS procedure was less.

Previous studies have confirmed that Pronase can improve the quality of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) images. Based on previous findings, this study hypothesized that Pronase could further shorten the duration of examination and reduce the usage of physiological saline during EUS examination through improving the quality of EUS images.

A few human studies have suggested that premedication with Pronase could improve endoscopic visualization. This study found that for EUS examination, preoperative application of Pronase could provide clearer ultrasound images, shorten the duration of EUS examination, and reduce the intraoperative usage of physiological saline.

This study aimed to analyze and evaluate the effect of pretreatment with Pronase on imaging quality, the duration of examination and the usage of physiological saline during the examination process in gastric endoscopic ultrasound.

With Pronase premedication, the EUS examination time was shorter and the amount of saline used during the EUS procedure was less.

This is an interesting study on the use of Pronase premedication during EUS examination. The authors analyzed the effects of premedication with Pronase for EUS examination of the stomach. Two blinded investigators assessed the obscurity scores for the EUS images.

| 1. | Byrne MF, Jowell PS. Gastrointestinal imaging: endoscopic ultrasound. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1631-1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Levy MJ, Heimbach JK, Gores GJ. Endoscopic ultrasound staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:244-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yoshinaga S, Hilmi IN, Kwek BE, Hara K, Goda K. Current status of endoscopic ultrasound for the upper gastrointestinal tract in Asia. Dig Endosc. 2015;27 Suppl 1:2-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lennon AM, Penman ID. Endoscopic ultrasound in cancer staging. Br Med Bull. 2007;84:81-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rösch T, Braig C, Gain T, Feuerbach S, Siewert JR, Schusdziarra V, Classen M. Staging of pancreatic and ampullary carcinoma by endoscopic ultrasonography. Comparison with conventional sonography, computed tomography, and angiography. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:188-199. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Snady H, Cooperman A, Siegel J. Endoscopic ultrasonography compared with computed tomography with ERCP in patients with obstructive jaundice or small peri-pancreatic mass. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boyce GA, Sivak MV, Rösch T, Classen M, Fleischer DE, Boyce HW, Lightdale CJ, Botet JF, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. Evaluation of submucosal upper gastrointestinal tract lesions by endoscopic ultrasound. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:449-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Adler DG, Diehl DL. Missed lesions in endoscopic ultrasound. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:165-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Altonbary AY, Deiab AG, Negm EH, El Sorogy MM, Elkashef WF. Endoscopic ultrasound of isolated gastric corrosive stricture mimicking linitis plastica. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bhutani MS, Arora A. New developments in endoscopic ultrasound-guided therapies. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:304-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Razavi SM, Khodadost M, Sohrabi M, Keshavarzi A, Zamani F, Rakhshani N, Ameli M, Sadeghi R, Hatami K, Ajdarkosh H. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography for determination of tumor invasion depth in gastric cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:3141-3145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alkaade S, Chahla E, Levy M. Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology, viscosity, and carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cyst fluid. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hata S, Arai M, Suzuki T, Maruoka D, Matsumura T, Nakagawa T, Katsuno T, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O. Clinical significance of endoscopic ultrasound for gastric submucosal tumors. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:207-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sakai N, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Nakaizumi A. Pre-medication with pronase reduces artefacts during endoscopic ultrasonography. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yiengpruksawan A, Lightdale CJ, Gerdes H, Botet JF. Mucolytic-antifoam solution for reduction of artifacts during endoscopic ultrasonography: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:543-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamamoto S, Nishida T, Kato M, Inoue T, Hayashi Y, Kondo J, Akasaka T, Yamada T, Shinzaki S, Iijima H. Evaluation of endoscopic ultrasound image quality is necessary in endosonographic assessment of early gastric cancer invasion depth. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:194530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rana SS, Sharma V, Sharma R, Gunjan D, Dhalaria L, Gupta R, Bhasin DK. Gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor mimicking cystic tumor of the pancreas: Diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-fine-needle aspiration. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:351-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tarentino AL, Maley F. Purification and properties of an endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Streptomyces griseus. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:811-817. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ambler RP. The purification and amino acid composition of pseudomonas cytochrome C-551. Biochem J. 1963;89:341-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Narahashi Y, Shibuya K, Yanagita M. Studies on proteolytic enzymes (pronase) of Streptomyces griseus K-1. II. Separation of exo- and endopeptidases of pronase. J Biochem. 1968;64:427-437. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kuo CH, Sheu BS, Kao AW, Wu CH, Chuang CH. A defoaming agent should be used with pronase premedication to improve visibility in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2002;34:531-534. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Fujii T, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Hirasawa R, Uedo N, Hifumi K, Omori M. Effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during gastroendoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:382-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Han JP, Hong SJ, Moon JH, Lee GH, Byun JM, Kim HJ, Choi HJ, Ko BM, Lee MS. Benefit of pronase in image quality during EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1230-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Woo JG, Kim TO, Kim HJ, Shin BC, Seo EH, Heo NY, Park J, Park SH, Yang SY, Moon YS. Determination of the optimal time for premedication with pronase, dimethylpolysiloxane, and sodium bicarbonate for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:389-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bhutani MS. Role of endoscopic ultrasound for pancreatic cystic lesions: Past, present, and future! Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:273-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lu X, Zhang S, Ma C, Peng C, Lv Y, Zou X. The diagnostic value of EUS in pancreatic cystic neoplasms compared with CT and MRI. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:324-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. The safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic cystic lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:289-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wilcox CM, Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi M. Role of endoscopic evaluation in idiopathic pancreatitis: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:1037-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hussain N, Hawes RH. Principles of endosonography and imaging. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2005;15:1-12, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Imaging in local staging of gastric cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2107-2116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Polkowski M, Larghi A, Weynand B, Boustière C, Giovannini M, Pujol B, Dumonceau JM. Learning, techniques, and complications of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44:190-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Everett SM, White KL, Schorah CJ, Calvert RJ, Skinner C, Miller D, Axon AT. In vivo DNA damage in gastric epithelial cells. Mutat Res. 2000;468:73-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chang CC, Chen SH, Lin CP, Hsieh CR, Lou HY, Suk FM, Pan S, Wu MS, Chen JN, Chen YF. Premedication with pronase or N-acetylcysteine improves visibility during gastroendoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:444-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chamberlain MC, Faloppi L, Jones G S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang FF