Published online Dec 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10471

Peer-review started: July 28, 2016

First decision: October 11, 2016

Revised: October 17, 2016

Accepted: October 27, 2016

Article in press: October 27, 2016

Published online: December 21, 2016

Processing time: 146 Days and 8.7 Hours

Gastric sarcoidosis with noncaseating granuloma is rare. Although corticosteroid produces a dramatic clinical response, it is unknown whether azathioprine show efficacy in prednisolone-dependent cases. Here, we report a case of gastric sarcoidosis in a 25-year-old man with severe epigastlargia. Gastroendoscopy revealed multiple map-like ulcerations. Histological examination showed multiple noncaseating granulomatous lesions in gastric mucosa, which were incompatible with diagnoses of Crohn’s disease or tuberculosis. He was started on prednisolone at 30 mg/d, and his symptoms improved within 7-d. The prednisolone was gradually tapered by 5 mg every 2-wk, but oral azathioprine at 50 mg was added after symptoms recurred at tapered dose of 10 mg. Endoscopy 4-wk later showed healing ulcers, and, lymphocytic infiltration was absent. The efficacy of additional azathioprine in gastric sarcoidosis is not well defined. Here, we report a case of prednisolone-dependent gastric sarcoidosis that improved after additional azathioprine, and also review the literature concerning the treatment, especially for prednisolone-dependent cases.

Core tip: Gastric sarcoidosis is often difficult to detect because of the relative lack of symptoms. Although the abdominal symptoms and endoscopic findings improve in most gastric sarcoidosis cases after corticosteroids, additional therapy, azathioprine, may be required to improve symptoms and to decrease the dosage of prednisolone.

- Citation: Murata M, Sugimoto M, Yokota Y, Ban H, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Kushima R, Andoh A. Efficacy of additional treatment with azathioprine in a patient with prednisolone-dependent gastric sarcoidosis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(47): 10471-10476

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i47/10471.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10471

Compared with the lung, heart, skin, eye and nervous system, it is rare for the gastrointestinal tract to be the primary organ affected by sarcoidosis. In a recent epidemiologic report, the prevalence of gastrointestinal sarcoidosis was only 1.6% among Japanese patients with sarcoidosis[1]. The stomach is the most commonly affected organ in gastrointestinal sarcoidosis[2]. Characteristically, most cases are asymptomatic and gastrointestinal symptoms are observed in only 0.1%-0.9% of patients[3]. The gastric lesions of sarcoidosis usually manifest as multiple erosions, stricture or stenosis on gastrointestinal X-ray fluoroscopy and endoscopy. The definitive diagnosis of gastric sarcoidosis requires histopathological evaluation of these lesions, which show noncaseating epithelioid granulomas. Gastric ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome need to be excluded. In addition, other causes of granulomatous gastritis, including Crohn’s disease, Whipple’s disease, reaction to malignancy or foreign body, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis and syphilis also need to be excluded[4]. With regard to pharmacological treatment, corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for gastric sarcoidosis with severe symptoms or any complication, and 66% of patients treated with a corticosteroid obtained relief of epigastralgia[4]. However, it is controversial whether administration of immunosuppressive agents, including azathioprine, is effective in patients who are corticosteroid-dependent or in refractory cases.

Here, we report a case of corticosteroid-dependent gastric sarcoidosis in which the dose of corticosteroid could be tapered by adding azathioprine. We also reviewed the literature concerning the treatment of gastric sarcoidosis, particularly for prednisolone-dependent or -refractory cases.

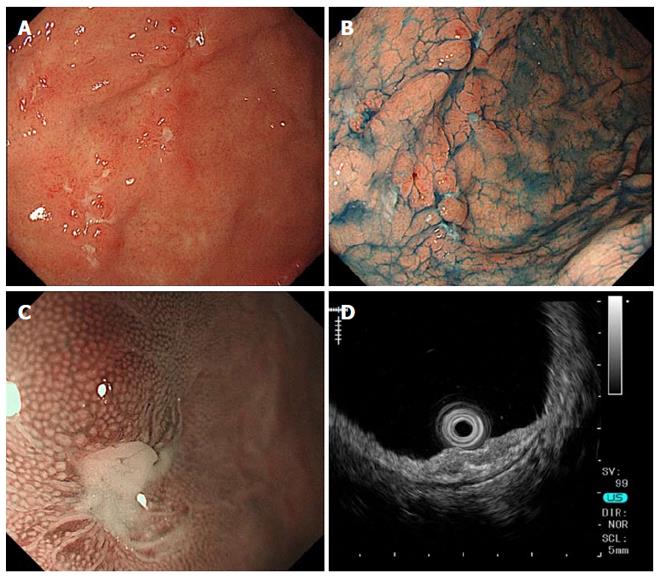

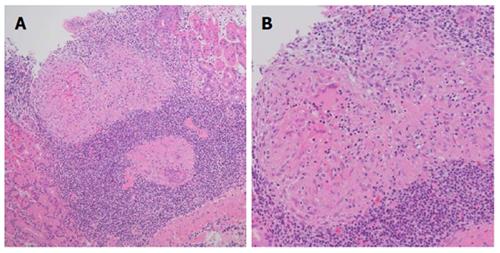

A 25-year-old Japanese man presented with hematemesis from a Dieulafoy’s lesion on the lesser curvature of the gastric body, accompanied by nausea, epigastric discomfort and severe epigastralgia. Gastric endoscopy showed multiple map-like ulcerative lesions and scars on the greater curvature of the body to fornix and atrophic gastritis with H. pylori infection (Figure 1A and B), while magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging showed no specific abnormal microsurface pattern and a microvascular pattern suggestive of a gastric cancerous lesion (Figure 1C). Endoscopic ultrasonography showed an irregular thickness of the second layer of the gastric wall without evidence of invasion into the third layer (Figure 1D). Histopathological findings of biopsy specimens from the ulcer edge revealed multiple noncaseating granulomatous lesions in the mucosal layer of the gastric wall (Figure 2A and B). In addition, there were no significant or specific histopathological findings suggestive of Crohn’s disease, Whipple’s disease, reaction to malignancy or foreign body, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis or syphilis. Chest computed tomography showed an infiltrative shadow and a pulmonary nodule, but no involvement of the heart, skin, eyes or nervous system. Despite administration of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and H. pylori eradication therapy with lansoprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin, his gastrointestinal symptoms and endoscopic findings did not improve in the three to six months after the initiation of therapy.

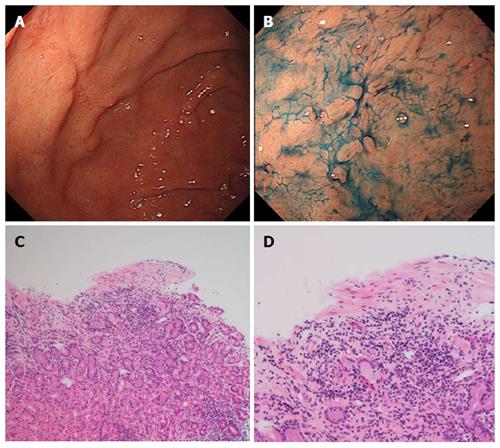

Gastric sarcoidosis was diagnosed based on the above results and a prednisolone was started orally at 30 mg per day. His gastrointestinal symptoms improved within 7 d. After improvement of symptoms, the dose of the prednisolone was gradually tapered by 5 mg every fortnight. However, similar symptoms recurred when the dose reached 10 mg, which was suggestive of corticosteroid-dependent gastric sarcoidosis. As an additional treatment, oral azathioprine at 50 mg was given, and alleviation of symptoms was achieved with 30 mg of prednisolone and 50 mg of azathioprine. Four weeks after combined treatment, endoscopy revealed healing ulcers (Figure 3A and 3B) and histopathologically, granuloma and infiltration of inflammatory cells were absent in the gastric mucosal tissue (Figure 3C and D). Although the prednisolone was gradually tapered, he has had no return of abdominal symptoms.

We reported a rare case of prednisolone-dependent gastric sarcoidosis that improved after additional azathioprine therapy. This case had multiple map-like ulcerative lesions and scars on endoscopy and severe abdominal symptoms caused by diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells and mucosal fibrosis that narrowed the gastric lumen. This case also showed upper gastrointestinal bleeding from Dieulafoy’s lesion in the lesser curvature of the gastric body; it has been reported that about 25% of gastric sarcoidosis patients present with upper gastrointestinal bleeding[5]. In most cases of systemic sarcoidosis and also gastric sarcoidosis, administration of corticosteroid is effective in improving symptoms and decreasing the activity of sarcoidosis. Although there is limited evidence for the efficacy of immunosuppressive agents in sarcoidosis, azathioprine may be an option in the treatment of prednisolone-depending gastric sarcoidosis.

The proportion of Japanese sarcoidosis patients with gastrointestinal sarcoidosis is only a few percent[1]. However, because gastric noncaseating granuloma formation has coincidentally been reported in up to 10% of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis[6,7], gastric sarcoidosis should be considered as a potential diagnosis even in patients who are under long-term observation for systemic sarcoidosis. In general, gastrointestinal screening by endoscopy is required for patients with sarcoidosis who have persistent or severe epigastric symptoms or upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Because a large number of gastric sarcoidosis cases are clinically asymptomatic, it is hard to clarify the incidence of gastric sarcoidosis.

Although infiltration of inflammatory cells and noncaseating granuloma formation in gastrointestinal sarcoidosis can be observed histopathologically in all layers from the mucosa to the subserosa, the diagnosis of gastric sarcoidosis is difficult to reach without evidence of sarcoidosis-related lesions in other organs. Histological evaluation is required to diagnose gastric sarcoidosis and to establish a definitive diagnosis of gastric sarcoidosis based on three components, as follows. First, there is histopathological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in the “symptomatic or incident organ”. Second, other granulomatous diseases, especially mycobacterial, fungal and parasitic infections, should be excluded. Third, clinical and radiographic evidence, and optimally, histopathologic evidence, of sarcoidosis in at least one other organ should be obtained[8]. This case was histopathologically proven to have noncaseating granulomas in the stomach without evidence of other granulomatous disease.

The treatment for gastric sarcoidosis depends on the status of symptoms, and asymptomatic patients do not require any specific therapy. Although anti-acid therapy, including PPIs, may have efficacy in gastric sarcoidosis as well as peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease, improvement with PPIs alone is limited[9]. Therefore, prednisone at 30 to 40 mg a day is the first-line treatment for symptomatic patients[4,5]. If symptoms and granulomas disappear histologically, prednisone is gradually tapered to a maintenance dose of 10 to 15 mg daily, guided by clinical response, over a period of approximately six months. In a case series, two-thirds of symptomatic gastric sarcoidosis patients on oral corticosteroids improved, while the remaining patients were refractory to corticosteroid therapy and required gastrectomy[5]. Additional treatment is required in prednisolone-dependent cases, refractory cases or cases with severe side effects, and azathioprine and methotrexate are second-line drugs for systemic sarcoidosis[10,11]. Studies have described the efficacy of azathioprine treatment in patients with systemic sarcoidosis affecting the lungs, skin, musculoskeletal system and nerves was reported[10-15]. At present, few cases of sarcoidosis are treated with azathioprine, and no randomized comparison trials or large case series have been reported. However, efficacy has been reported in small case series and case reports[10-15]; in these studies, azathioprine was generally used as a supplement to corticosteroid rather than as a single drug[14,16-19], and 50%-73% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis exhibited clinical improvement. Azathioprine affects the synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid, thereby inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation. Cellular immunity is suppressed to a greater degree than humoral immunity, but the exact mechanism is not clear. Although the role of immunosuppressive therapy in gastric sarcoidosis is not well defined, in 2008, Leeds et al[20] reported the case of a patient with gastric sarcoidosis who presented with irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms but who subsequently responded to azathioprine. In our patient with prednisolone-dependent gastric sarcoidosis, additional azathioprine therapy dramatically improved the severe gastric symptoms, suggesting that azathioprine may be an option in refractory cases.

There is no evidence for the optimal duration of azathioprine treatment for sarcoidosis patients. Azathioprine treatment often results in gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting and diarrhea), pancytopenia, hepatotoxicity and infection[21]. Particularly in patients with rheumatism and inflammatory bowel disease, chronic immunosuppression with azathioprine increases the risk of malignancy, including post-transplant lymphoma and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma[22,23]. The development of complications and adverse effects should therefore be considered.

Gastric sarcoidosis is often difficult to detect because of the relative lack of symptoms, and its diagnosis requires evidence of the involvement of other organs. We experienced a rare case of prednisolone-dependent gastric sarcoidosis that improved after additional azathioprine therapy. Although the abdominal symptoms and endoscopic findings improve in most gastric sarcoidosis cases after corticosteroids, additional therapy may be required to improve symptoms and to decrease the dosage of prednisolone. Although the accumulation of additional cases is needed to determine the optimal treatment of gastric sarcoidosis, our present case indicates that azathioprine is effective for steroid-dependent gastric sarcoidosis.

A 25-year-old Japanese man presented with hematemesis, accompanied by nausea, epigastric discomfort and severe epigastralgia.

Strong epigastric tenderness.

Multiple gastric ulcers in fornix to body caused by Helicobacter pylori infection, intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, Crohn’s disease, Whipple’s disease, reaction to malignancy or foreign body, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis or syphilis.

All lab orateries including liver function, renal function were within normal limits.

Gastroendoscopy revealed multiple map-like gastric ulcerations in for fix to body.

Pathological examination showed multiple noncaseating granulomatous lesions in gastric mucosa, which were incompatible with diagnoses of Crohn’s disease or tuberculosis.

In corticosteroid-dependent gastric sarcoidosis, an additional treatment with azathioprine was performed and the dose of corticosteroid could be tapered after improvement of abdominal symptoms.

Additional treatment of azathioprine and methotrexate as second-line drugs is required for prednisolone-dependent gastric sarcoidosis cases, refractory cases or cases with severe side effects.

Although the abdominal symptoms and endoscopic findings improve in most of gastric sarcoidosis cases after oral administration of corticosteroids, additional therapy may be required to improve symptoms and to decrease the dosage of prednisolone in prednisolone-dependent cases, refractory cases or cases with severe side effects.

The paper is well written.

| 1. | Morimoto T, Azuma A, Abe S, Usuki J, Kudoh S, Sugisaki K, Oritsu M, Nukiwa T. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Japan. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:372-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schaumann J. Lymphogranulomatosis benigna in the light of prolonged clinical observations and autopsy findings. Br J Dermatol Syphilis. 1936;48:399-446. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharma AM, Kadakia J, Sharma OP. Gastrointestinal sarcoidosi. In: Seminars in Respiratory Medicine. Thieme Medical Publishers 1992; 442-449. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ebert EC, Kierson M, Hagspiel KD. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3184-3192; quiz 3193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chinitz MA, Brandt LJ, Frank MS, Frager D, Sablay L. Symptomatic sarcoidosis of the stomach. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30:682-688. [PubMed] |

| 6. | PALMER ED. Note on silent sarcoidosis of the gastric mucosa. J Lab Clin Med. 1958;52:231-234. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bratkovskiĭ MV, Magalif NI. [Sarcoidosis of the stomach]. Probl Tuberk. 1990;28-30. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Govender P, Berman JS. The Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:585-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Inomata M, Ikushima S, Awano N, Kondoh K, Satake K, Masuo M, Moriya A, Kamiya H, Ando T, Azuma A. Upper gastrointestinal sarcoidosis: report of three cases. Intern Med. 2012;51:1689-1694. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Schutt AC, Bullington WM, Judson MA. Pharmacotherapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a Delphi consensus study. Respir Med. 2010;104:717-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baughman RP, Nunes H. Therapy for sarcoidosis: evidence-based recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:95-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pacheco Y, Marechal C, Marechal F, Biot N, Perrin Fayolle M. Azathioprine treatment of chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1985;2:107-113. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lewis SJ, Ainslie GM, Bateman ED. Efficacy of azathioprine as second-line treatment in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:87-92. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Müller-Quernheim J, Kienast K, Held M, Pfeifer S, Costabel U. Treatment of chronic sarcoidosis with an azathioprine/prednisolone regimen. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1117-1122. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Baughman RP, Lower EE. Alternatives to corticosteroids in the treatment of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1997;14:121-130. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, Greaves MS, Hansell DM, Harrison NK, Hirani N, Hubbard R, Lake F, Millar AB. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63 Suppl 5:v1-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Baughman RP. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:521-530, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Agbogu BN, Stern BJ, Sewell C, Yang G. Therapeutic considerations in patients with refractory neurosarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:875-879. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Gelwan MJ, Kellen RI, Burde RM, Kupersmith MJ. Sarcoidosis of the anterior visual pathway: successes and failures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:1473-1480. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Leeds JS, McAlindon ME, Lorenz E, Dube AK, Sanders DS. Gastric sarcoidosis mimicking irritable bowel syndrome--cause not association? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4754-4756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dubinsky MC, Lamothe S, Yang HY, Targan SR, Sinnett D, Théorêt Y, Seidman EG. Pharmacogenomics and metabolite measurement for 6-mercaptopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:705-713. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Asten P, Barrett J, Symmons D. Risk of developing certain malignancies is related to duration of immunosuppressive drug exposure in patients with rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1705-1714. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Hamzeh NY, Matsubara T S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX