Published online Nov 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9860

Peer-review started: July 5, 2016

First decision: August 8, 2016

Revised: September 7, 2016

Accepted: September 14, 2016

Article in press: September 14, 2016

Published online: November 28, 2016

Processing time: 148 Days and 21.5 Hours

Bleeding resulting from spontaneous rupture of the liver is an infrequent but potentially life threatening complication that may be associated with an underlying liver disease. A hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatic adenoma is frequently reported is such cases. However, hemoperitoneum resulting from a hepatic metastatic thymoma is extremely rare. Here, we present a case of a 62-year-old man with hypovolemic shock induced by ruptured hepatic metastasis from a thymoma. At the first hospital admission, the patient had a 45-mm anterior mediastinal mass that was eventually diagnosed as a type A thymoma. The mass was excised, and the patient was disease-free for 6 years. He experienced sudden-onset right upper quadrant pain and was again admitted to our hospital. We noted large hemoperitoneum with a 10-cm encapsulated mass in S5/8 and a 2.3-cm nodular lesion in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. He was diagnosed with hepatic metastasis from the thymoma, and he underwent chemotherapy and surgical excision.

Core tip: Spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from a thymoma is extremely rare. This case report presents a rare case of spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from a thymoma and describes its management. To our knowledge, no such case of rupture of a metastatic liver tumor associated with a thymoma has been reported previously.

- Citation: Kim HJ, Park YE, Ki MS, Lee SJ, Beom SH, Han DH, Park YN, Park JY. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from a thymoma: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(44): 9860-9864

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i44/9860.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9860

The most common cause of a tumor in the anterior mediastinum is a thymic tumor. They have the ability to invade local structures and the capacity to metastasize to distant organs. The sites of metastasis include the lymph nodes, lungs, bones, liver, spleen, brain, and adrenal glands. However, hepatic metastasis is uncommon, and it is extremely rare for a metastatic liver tumor to rupture and cause hemoperitoneum. Recently, we experienced a patient who underwent transarterial chemoembolization for spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from a thymoma. Here, we present this extremely rare case. To our knowledge, no such case of rupture of a metastatic liver tumor associated with a thymoma has been reported previously.

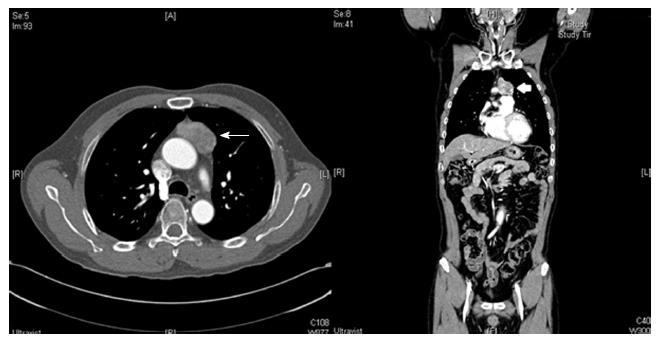

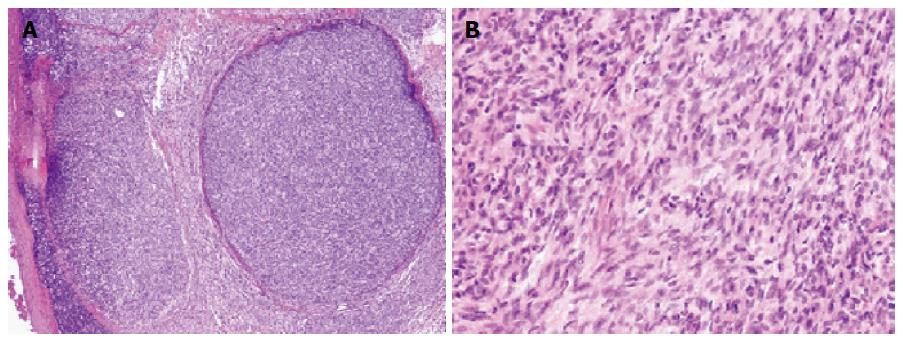

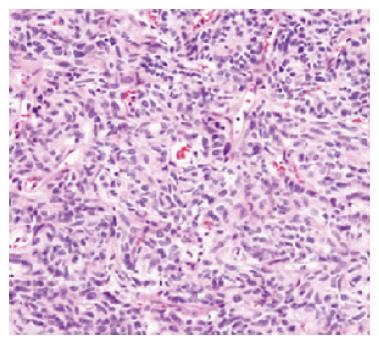

A 62-year-old man underwent an annual health checkup. A chest radiogram obtained during the checkup showed widening of the mediastinum. Chest computed tomography showed a 45-mm anterior mediastinal mass (Figure 1), and he underwent excision of the mass. A biopsy specimen from the mass demonstrated that the tumor was a type A thymoma according to the World Health Organization classification system, with fat tissue invasion. The tumor included bland spindle cells and few lymphocytes (Figure 2). According to the Masaoka classification system, the tumor stage was IIA, and he received radiotherapy (total 50 Gy in 25 fractions).

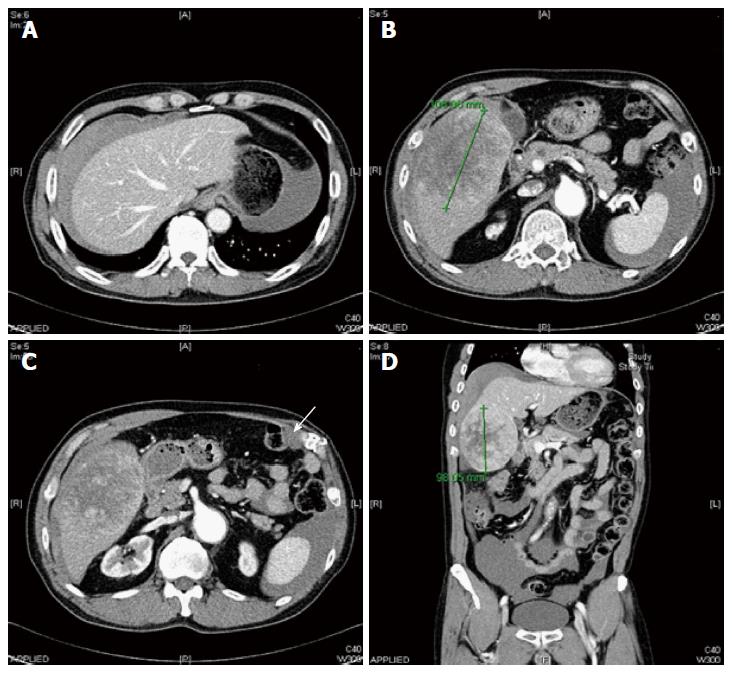

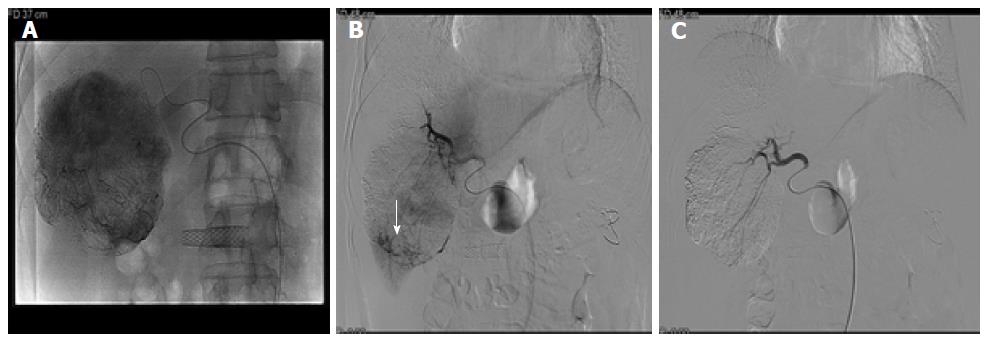

He was disease-free for 6 years; however, he experienced sudden-onset right upper quadrant pain and was referred to our hospital. He did not have a history of abdominal trauma and did not experience fever, vomiting, or diarrhea. On examination, his blood pressure was 77/50 mmHg and pulse rate was 70 beats/min. Blood analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 15370/mm3 (reference range, 4000-10800/mm3), hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 13-17.4 g/dL), platelet count of 154000/mm3 (reference range, 150000-400000/mm3), C-reactive protein level of 6 mg/L (reference range, 0-8 mg/L), aspartate aminotransferase level of 19 IU/L (reference range, 13-34 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase level of 17 IU/L (reference range, 5-46 IU/L), and alkaline phosphatase level of 40 IU/L (reference range, 47-143 IU/L). Abdominal computed tomography revealed large hemoperitoneum with a 10-cm encapsulated mass in S5/8 and a 2.3-cm nodular lesion in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (Figure 3). The tumor marker (α-fetoprotein and prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II) levels were within the reference limits (2.3 ng/mL and 10 mAU/mL, respectively). Based on these findings, he underwent emergency angiography, and an interventional radiologist embolized the vessel supplying the tumor (Figure 4). Five days after embolization, when the patient was stable, abdominal wall biopsy was performed under general anesthesia. Histopathological analysis indicated a metastatic type A thymoma (Figure 5). He was transferred to the oncology department and underwent chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2 day 1), doxorubicin (50 mg/m2 day 1), and cisplatin (50 mg/m2 day 1). After 4 cycles of chemotherapy, segmentectomy of the hepatic metastasis was performed and liver biopsy showed histopathology similar to a thymoma.

Spontaneous rupture of hepatic tumors usually occurs without warning in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and it is regarded as one of the most serious conditions associated with HCC[1]. However, hemoperitoneum induced by rupture of a metastatic liver tumor is extremely. Ruptured metastatic liver tumors originating from various cancers, such as cancers of the lung, breast, testicle, gallbladder, stomach, kidney, skin, and nasopharynx; choriocarcinoma; and hepatic lymphoma, have been reported[2]; however, to our knowledge, this is the first report to describe a ruptured metastatic liver tumor that originated from a thymoma.

Thymic tumors are derived from thymic epithelial cells, and are located mainly in the anterior mediastinum. About 90% of thymic tumors are located in the anterior mediastinum and some are found in other mediastinal areas. However, the incidence of thymoma is very low, and has been shown to be 0.15 cases per 100000 population. The disease progression is very slow, the condition remains silent for many years, and the tumor is generally incidentally identified[3]. A multidisciplinary approach is essential in the management of a thymoma. If complete resection of the primary cancer appears possible, surgery is an important treatment approach for thymic tumors. Adjuvant radiotherapy has been widely used to improve survival or reduce the tumor in cases of late-stage cancer, especially when the tumor penetrates adjacent tissues or when the tumor is incompletely resected. Systemic chemotherapy is currently considered as the standard treatment approach for metastatic or inoperable tumors[4].

A thymoma is capable of both local invasion and intrathoracic recurrence, and local recurrence is common. The sites of metastasis include the brain, spleen, adrenal glands, bones, lymph nodes, liver, and lungs. The lung is considered the most frequent location of distant metastasis, while the liver has a relatively lower incidence of metastasis, and hepatic metastasis represents 12.5%-33.5% of all metastatic cases[3]. Hemoperitoneum originating from a metastatic thymoma is extremely rare.

Treatment of hemoperitoneum secondary to hepatic metastasis depends on tumor location, tumor size, and bleeding severity. The primary goal should be complete hemostasis[5]. There are different treatment options for patients presenting with hepatic rupture. These treatment options vary from conservative management to more invasive procedures, such as hepatectomy and transarterial embolization (TAE). A previous study compared different treatment options for hepatic rupture and concluded that the survival rate is better with hepatectomy than with TAE[6]. Although hepatic resection may be a definitive treatment for bleeding, most patients have impaired liver function and an unstable hemodynamic status, and therefore, cannot tolerate surgery. In such cases, TAE and conservative management have been used to control bleeding after hepatic rupture[7]. With regard to HCC rupture, the risk of mortality is higher with conservative management than with TAE. Thus, in emergencies, TAE is frequently performed as initial therapy. Hemoperitoneum secondary to hepatic metastasis from a choriocarcinoma and a gastrointestinal stromal tumor has been successfully treated with TAE[2,8]. However, care should be taken, as artery embolization is associated with complications, such as re-bleeding and peritoneal seeding. Massive peritoneal washing with saline solution has been shown to reduce the chance of peritoneal implantation[9]. Additionally, to reduce the chance of recurrent bleeding, TAE can be used as a bridge to hepatectomy. A previous report showed the favorable outcomes of delayed hepatectomy after emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for hepatic rupture[10]. Additionally, in a previous study, patients treated with staged hepatectomy had the highest survival rate[1]. In our case, we managed the ruptured hepatic tumor with arterial embolization owing to hypovolemic shock. Complete hemostasis was achieved, and delayed hepatectomy was performed for the hepatic metastasis.

In conclusion, we presented a rare case of spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from a thymoma and described its management.

A 62-year-old Asian man with a thymoma visited the emergency room after experiencing whole abdominal pain.

Hemoperitoneum.

Septic shock due to pan-peritonitis.

The hemoglobin level was 10.5 g/dL, and tumor markers (α-fetoprotein and prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II) were negative.

Abdominal computed tomography revealed large hemoperitoneum with a 10-cm encapsulated mass in S5/8 and a 2.3-cm nodular lesion in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

The thymoma and metastatic liver tumor were composed of fibroblast-like spindle cells.

Transarterial embolization (TAE) and delayed hepatectomy were performed.

TAE is an excellent treatment option for hemoperitoneum secondary to hepatic metastasis from a thymoma.

No such case of rupture of a metastatic liver tumor associated with a thymoma has been reported previously.

| 1. | Rijckborst V, Ter Borg MJ, Tjwa ET, Sprengers D, Verhoef K, Moelker A, Ijzermans JN, de Man RA. Short article: Management of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma in a European tertiary care center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:963-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Duan YF, Tan Y, Yuan B, Zhu F. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic metastasis from small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of maxillary sinus. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scorsetti M, Leo F, Trama A, D’Angelillo R, Serpico D, Macerelli M, Zucali P, Gatta G, Garassino MC. Thymoma and thymic carcinomas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;99:332-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Gubens MA. Treatment updates in advanced thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:527-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Casillas VJ, Amendola MA, Gascue A, Pinnar N, Levi JU, Perez JM. Imaging of nontraumatic hemorrhagic hepatic lesions. Radiographics. 2000;20:367-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhong F, Cheng XS, He K, Sun SB, Zhou J, Chen HM. Treatment outcomes of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma with hemorrhagic shock: a multicenter study. Springerplus. 2016;5:1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sada H, Ohira M, Kobayashi T, Tashiro H, Chayama K, Ohdan H. An Analysis of Surgical Treatment for the Spontaneous Rupture of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2016;33:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu YH, Ma HX, Ji B, Cao DB. Spontaneous hemoperitoneum from hepatic metastatic trophoblastic tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4237-4240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bassi N, Caratozzolo E, Bonariol L, Ruffolo C, Bridda A, Padoan L, Antoniutti M, Massani M. Management of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1221-1225. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Takebayashi T, Kondo S, Ambo Y, Hirano S, Omi M, Morikawa T, Okushiba S, Katoh H. Staged hepatectomy following arterial embolization for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1074-1076. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Anis S, Teng Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF