Published online Nov 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i43.9631

Peer-review started: August 21, 2016

First decision: September 5, 2016

Revised: September 19, 2016

Accepted: October 10, 2016

Article in press: October 10, 2016

Published online: November 21, 2016

Processing time: 92 Days and 12.6 Hours

To investigate the possible long-term psychological harm of participating in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in Norway.

In a prospective, randomized trial, 14294 participants (aged 50-74 years) were invited to either flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) screening, or a faecal immunochemical test (FIT) (1:1). In total, 4422 screening participants (32%) completed the questionnaire, which consisted of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the SF-12, a generic health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measurement, when invited to screening and one year after the invitation. A control group of 7650 individuals was invited to complete the questionnaire only, at baseline and one year after, and 1911 (25%) completed the questionnaires.

Receiving a positive or negative screening result and participating in the two different screening modalities did not cause clinically relevant mean changes in anxiety, depression or HRQOL after one year. FS screening, but not FIT, was associated with an increased probability of being an anxiety case (score ≥ 8) at the one-year follow-up (5.6% of FS participants transitioned from being not anxious to anxious, while 3.0% experienced the reverse). This increase was moderately significantly different from the changes in the control group (in which the corresponding numbers were 4.8% and 4.5%, respectively), P = 0.06.

Most individuals do not experience psychological effects of CRC screening participation after one year, while FS participation is associated with increased anxiety for a smaller group.

Core tip: Participation in cancer screening programmes might cause worries in the population outweighing the benefits of screening. However, the results from studies of psychological harm of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening remain inconsistent. This is the first randomized study to investigate long-term changes in anxiety from before CRC screening, and compare these changes to individuals not invited to screening. Based on sound methodology, our study show that most individuals have no psychological effect of receiving a positive screening result, or participating in CRC screening after one year. However, flexible sigmoidoscopy participation is associated with increased anxiety for a smaller, possibly anxious group.

- Citation: Kirkøen B, Berstad P, Botteri E, Bernklev L, El-Safadi B, Hoff G, de Lange T, Bernklev T. Psychological effects of colorectal cancer screening: Participants vs individuals not invited. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(43): 9631-9641

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i43/9631.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i43.9631

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most frequent causes of cancer-related deaths in both men and women in developed countries[1]. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that screening for CRC can reduce CRC incidence and mortality[2-4]. However, the total benefits and harm of national cancer screening programs are under debate. To save relatively few lives, a large number of people need to be screened[4]. The majority of participants will never develop cancer, but they may experience psychological stress from participation in the screening program.

Many studies report that receipt of a positive faecal occult blood test (FOBT) result is associated with anxiety in screening participants[5-9]. However, few studies have measured the long-term psychological consequences of CRC screening[6,8,10-12], and the results of these studies are inconsistent. Only one study measured within-group changes[11], and no studies have investigated the long-term changes in anxiety from before screening and compared these changes to those of individuals not invited to screening. Thus, knowledge of the long-term psychological effects of participating in CRC screening is limited.

The incidence of CRC in Norway, has increased rapidly since the 1950s[13], and the lifetime risk of developing CRC for the average population is approximately 6%[14]. Accordingly, a randomized management trial, Bowel Cancer Screening in Norway (the BCSN pilot), was started in 2012 to compare the possible benefit of the two different screening modalities faecal immunochemical test (FIT) and flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS), on reductions in CRC incidence and mortality[15]. To evaluate the possible psychological harm of participation in the BCSN pilot, a sub-study was initiated. A random sample of the original cohort was invited to participate in the sub-study. The results of the short-term effects showed that receiving a positive CRC screening result or participating in CRC screening did not cause short-term anxiety, depression or decreased health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in participants[16].

The primary aim of the current sub-study was to measure the long-term changes in anxiety, depression and HRQOL in participants receiving different primary screening results and in participants completing two different screening modalities during a one-year follow-up study. The secondary aim was to investigate whether the potential psychological changes observed were different or similar to changes in a control group.

In the BCSN pilot, 140000 men and women aged 50-74 years in two defined geographical areas in South-East Norway are invited. From 2012-2018, they are randomized to receive an invitation to either a FS examination or screening with FIT (1:1). Individuals randomized to FIT receive a kit for taking a stool sample. Participants with a positive FS or FIT are invited to a work-up colonoscopy examination. In the present study, we invited a sub-sample of those invited to the main trial. A control group of sex- and age-matched individuals living in neighboring counties was randomly drawn from the Norwegian National Registry and invited to participate in the questionnaire study only.

Participants were invited to screening between September 2013 and July 2014 (FS group) and from October until December 2013 (FIT group). All participants received a questionnaire with the invitation together with a letter asking them to complete and return the questionnaire by a pre-paid return envelope or to complete the questionnaire online. One reminder was sent to participants who did not attend screening, but no reminders were sent to non-responders of the questionnaire. One year after the first invitation, participants who had completed the baseline questionnaire were invited to complete the questionnaire again.

The participant questionnaire consisted of two outcome measurements: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) and the generic HRQOL questionnaire Short-Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12). Both measurements have been translated into Norwegian and validated in Norwegian background populations[17-19].

The HADS consists of 14 questions, seven measuring anxiety and seven measuring depression[20]. Each question has four response options, ranging from 0-3, with a maximum total score of 21 for each scale. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety or depression. For participants who lacked a response to one or two items on one subscale, missing values were substituted by the mean of the completed item scores. The subscale score of participants who lacked more than two items was set to missing.

The SF-12 consists of 12 questions; each question has response choices varying from two to six alternatives[21]. The 12 questions can be transformed into eight dimensional scores covering the physical and mental aspects of HRQOL. These dimensions are physical functioning (PF), role-physical (limitation associated with physical problems, RP), role-emotional (limitations associated with emotional problems, RE), mental health (MH), general health (GH), bodily pain (BP), vitality (energy and happiness, VT), and social functioning (SF). The dimension scores range from 0-100, with higher scores indicating better HRQOL. Missing values were imputed following the recommendations of Ware and Kosinski[22]. If it was impossible to compute the value for one dimension, that dimensional score was deemed missing.

A positive FS is defined as the detection of advanced neoplasia (CRC, adenoma ≥ 10 mm, 3 or more adenomas, any polyp ≥ 10 mm, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia or villous components), and a positive FIT screening result is defined as the detection of human blood in the stool sample (cut-off > 75 µg/L). Participants with a positive FS or FIT are referred for a colonoscopy. The main objective of this study was to investigate the potential anxiety caused by participation in a screening program among healthy participants who did not have screening-detected CRC. Thus, participants diagnosed with CRC from screening were excluded from the analyses.

For the HADS scale, cut-off levels are defined as a score of ≥ 8 for the possible presence of and ≥ 11 for the probable presence of “clinically meaningful degrees of mood disorder”[20]. In the current study, a score of ≥ 8 was defined as the cut-off for caseness for HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression, based on the results of a study of Norwegian patients visiting primary care physicians[23].

Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The criterion for a clinically relevant mean change was defined as a change of ½ SD[24], indicating the smallest change perceived by individuals as an actual change in condition. Cohen classified different effect sizes and defined a Cohen’s d effect size above 0.5 as a medium effect size, or a clinically relevant change[25]. Therefore, our second criteria for a clinically relevant change was a value of Cohen’s d above 0.5.

Participants first received the questionnaire with an invitation to CRC screening (baseline). They received the questionnaire for the second time with the results of their primary screening test (result), but before undergoing a potential colonoscopy. Six and 12 mo after receiving the invitation to screening, when participants had learned of their final screening results, participants who had completed the questionnaire at baseline received the questionnaire again. Control participants were invited to complete the questionnaire at baseline and at 6 and 12 mo following the first questionnaire.

The date of completion of the questionnaire was used to determine whether it had been completed before or after participation in screening. Consequently, questionnaires lacking a completion date were excluded. We were interested in the short-term reactions to the primary screening test results in the second questionnaire. Therefore, result-questionnaires completed more than 60 d after the primary screening result or after work-up colonoscopy were excluded from the analyses of 4 time points. We accepted questionnaires that were completed within 5-8 mo following the invitation date as the 6-mo questionnaire, and questionnaires completed 11-15 mo after invitation were included as 1-year questionnaires.

Information regarding participants’ nationality, marital status, education and occupation was obtained through the questionnaire. Education level was classified as low (primary school/high school) or high (minimum two years of college/university). Information regarding age and gender was obtained from the Norwegian National Registry.

The number of individuals invited to participate in the psychological questionnaire study was 7270 for the FS group, 7024 for the FIT group, and 7650 for the control group. Participants who completed the questionnaire at baseline and after 1 year, as well as the screening examination for FS and FIT participants, were included in the main analyses. Additional analyses investigated changes over 4 time points, including all completed questionnaires.

Participants were ineligible for inclusion in the analyses if they had a previous CRC diagnosis or were deceased. Unattainable participants (invitation returned to sender) and participants who had moved out of the county were excluded. This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of South-East Norway (REK approval no 2011/1272).

To investigate the demographic differences between the three groups prior to screening, χ2 tests were applied for categorical outcomes and ANOVA for continuous outcomes. Significant differences in the ANOVA analysis were further examined by contrast analysis to determine which groups differed from each other. The internal consistency of the two HADS subscales was tested by Cronbach’s alpha.

To test for two- and three-way interaction effects between time (baseline and 1-year follow-up), primary screening results (positive and negative) and screening group (FIT and FS) on the outcome variables, ANOVAs analyses were applied. Next, we compared the mean change scores (from baseline to one-year follow-up) of the groups with positive and negative screening results, as well as of the two screening groups, with the change score in the control group. These analyses were completed with and without adjustment for participants’ baseline values for the outcome. To investigate whether there were significant changes in outcome variables during the four time points, mixed models were applied, including all completed questionnaires at each time point. Two sensitivity analyses, using repeated measures ANOVA, were performed with the same aim for participants with complete data only (including only participants who had completed the questionnaire at all four time points) and for all participants who completed the baseline questionnaire, with participants’ last completed questionnaire score carried forward when missing. Repeated measures analyses for binary outcomes were applied to test whether there were significant changes in the prevalence of participants with a score above the cut-off levels of anxiety and depression from baseline to one-year follow-up. Furthermore, we tested whether this change differed from the changes observed in the control group. These analyses were conducted with and without participants referred for surveillance colonoscopies. Age, sex, education, nationality, marital status and employment (and other HADS-score for HADS analyses) were included in all models to adjust for the effects of these variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v19 software. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by statistician Edoardo Botteri from Cancer Registry of Norway.

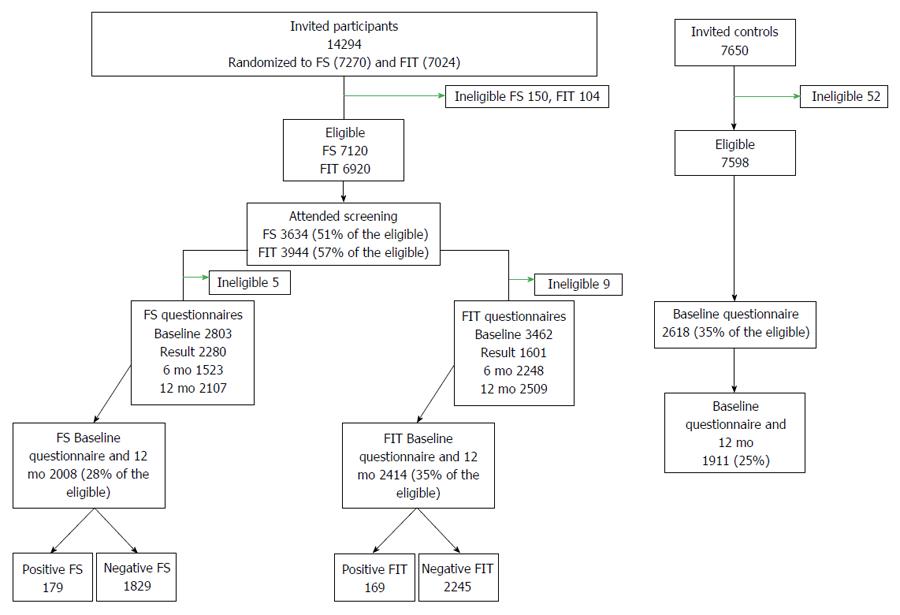

Of the 14294 individuals invited to screening, 7578 (53%) completed screening, of whom 4434 (32% of invited) completed the questionnaire both at invitation and at one-year follow-up: 2017 in the FS group and 2417 in the FIT group, respectively (Figure 1). Participants who received a CRC diagnosis during screening (13 in the FS and 12 in the FIT group) were excluded from all analyses. The 12-mo follow-up questionnaires were completed on an average of 340 d (range 88-426 FS) and 366 d (range 89-438 FIT) after screening participation, and 330 d (range 83-416) after colonoscopy for the screening positive. Among the individuals invited to the control group, 1911 (25%) completed the baseline and one-year follow-up questionnaires. Furthermore, 895 FS participants (13%) and 885 FIT participants (13%) completed the questionnaire at the four predefined time points.

The demographic data for each randomized group is shown in Table 1. The FS group displayed a higher mean age (M = 63.5 years, SD = 7.0) compared to the FIT group (M = 62.5 years, SD = 6.6), P < 0.01, as well as the control group (M = 62.7 years, SD = 6.8), P < 0.01. The HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression subscales had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.86 and 0.84, indicating good internal consistency.

| FS (Std residual) | FIT (Std residual) | Control (Std residual) | P comparing 3 groups | |

| Norwegian nationality, % | 95.9% (0.4) | 94.6% (-0.2) | 94.5% (-0.2) | 0.08 |

| Not married/cohabitant, % | 18.0% (-2.0)1 | 20.0% (0.0) | 22.0% (2.0)1 | < 0.01 |

| Higher education, % | 45.3% (-0.8) | 43.6% (-2.1)1 | 51.7% (3.2)1 | < 0.01 |

| Employed, % | 48.9% (-0.9) | 49.6% (-0.6) | 52.9% (1.6)1 | 0.03 |

| Women, % | 50.1% (-1.0) | 52.4% (0.6) | 52.2% (0.4) | 0.25 |

| Mean age, yr | 63.5 | 62.5 | 62.7 | < 0.012 |

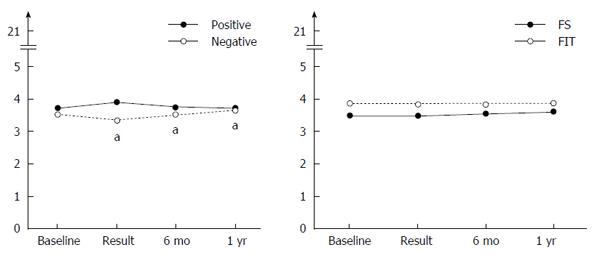

Figure 2 shows participants’ scores at baseline, after receiving screening results, after 6 mo and after 1 year, including all completed questionnaires (for n, see Figure 1). Participants’ level of anxiety depended on both the screening results (positive versus negative) and time, P = 0.04. Anxiety increased immediately after a positive result and decreased afterwards, while anxiety decreased after a negative result and increased afterwards. Participants with negative results reported statistically significantly less anxiety when receiving their results compared to baseline, which was also observed in the analyses of complete cases only and analyses with the last value carried forward (though the interaction effect was not significant). Some temporary improvements in HRQOL were observed (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

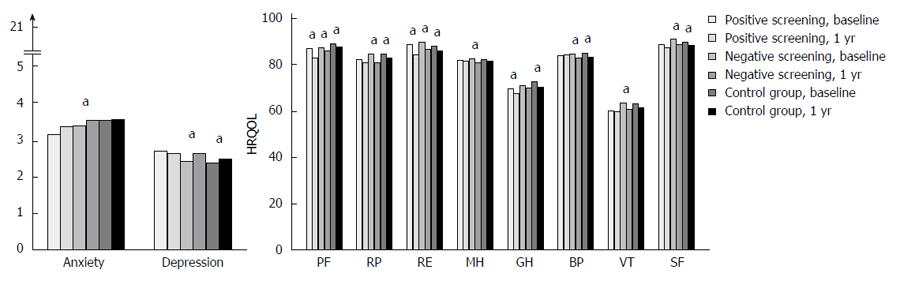

Participants’ scores for anxiety, depression and HRQOL at baseline and at 1 year follow up are shown in Figure 3. No statistically significant changes in anxiety were observed in participants with positive screening results from baseline to one-year follow-up. Table 2 shows the change in scores within each screening group compared to the changes in the control group. The only significant difference in change scores between participants with positive results and the control group was that participants with positive results had a greater worsening in the HRQOL dimension PF (M = -3.83 vs M = -1.16, P = 0.01, respectively).

| Control group | Positive | Negative | FS | FIT | Screening group | |

| (Cohen’s d) | (Cohen’s d) | (Cohen’s d) | (Cohen’s d) | (Cohen’s d) | ||

| Anxiety | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| (-0.03) | (-0.04) | (-0.05) | (-0.02) | (-0.04) | ||

| Depression | 0.15 | -0.06 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| (0.10) | (-0.02) | (-0.02) | (-0.01) | (-0.02) | ||

| SF-12 | ||||||

| PF | -1.16 | -3.831 | -1.50 | -1.13 | -2.12 | -1.71 |

| (0.14) | (0.02) | (-0.01) | (0.05) | (0.03) | ||

| RP | -1.86 | -0.97 | -3.54 | -4.051 | -2.77 | -3.39 |

| (-0.03) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.04) | ||

| RE | -2.03 | -3.37 | -2.89 | -2.04 | -3.67 | -2.99 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.05) | (0.03) | ||

| MH | -0.41 | -0.58 | -1.28 | -1.23 | -1.20 | -1.23 |

| (0.01) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | ||

| GH | -1.81 | -2.09 | -0.451 | 0.061 | -1.08 | -0.571 |

| (0.02) | (-0.09) | (-0.12) | (-0.05) | (-0.08) | ||

| BP | -1.57 | 0.57 | -1.11 | -0.73 | -1.18 | -1.01 |

| (-0.11) | (-0.02) | (-0.04) | (-0.02) | (-0.03) | ||

| VT | -1.44 | -0.19 | -1.93 | -1.24 | -2.20 | -1.8 |

| (-0.06) | (0.02) | (-0.01) | (0.04) | (0.02) | ||

| SF | -1.10 | -1.35 | -1.47 | -1.50 | -1.38 | -1.46 |

| (0.01) | (0.02) | (-0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) |

At the 1-year follow-up, participants with negative results reported significantly more anxiety and a decreased HRQOL score compared to baseline (Figure 3). However, only the change in GH significantly differed from the control group, with the negative results group showing a smaller worsening in GH (Table 2).

The change scores observed in the FIT screening group were not statistically different from the changes in the control group (Table 2). FS participants showed a statistically significantly smaller worsening in GH and a greater worsening in RP compared to the changes in the control group.

Additionally, a significant increase in cases of anxiety (score ≥ 8) was observed among screening participants and FS participants from baseline to one year after screening (Table 3). However, the observed change in the screening group did not significantly differ from the change in the control group, P = 0.11. The increase in cases of anxiety within the FS group was marginally significantly different from the change observed in the control group, P = 0.06. The FS participants who changed from being non-cases to cases of anxiety had both a higher mean anxiety score (M = 5.2, SD = 1.9 vs M = 3.4, SD = 3.3) prior to screening and a higher mean change score (M = 4.4, SD = 2.7 vs M = 0.13, SD = 2.3) compared to the other screening participants. However, they did not differ from the other screening participants in terms of screening results or demographic variables.

| Group | Anxiety at 1 yr follow up | P value1 | P value2 | |||

| Non anxiety | Anxiety case | |||||

| Control group | Before screening | Non anxiety | 1574 (82.5) | 91 (4.8) | ||

| Anxiety case | 87 (4.5) | 57 (8.2) | 0.82 | Ref. | ||

| Screening | Before screening | Non anxiety | 3660 (82.9) | 250 (5.7) | ||

| Anxiety case | 164 (3.6) | 343 (7.8) | < 0.01 | 0.11 | ||

| FS screening | Before screening | Non anxiety | 1683 (84.0) | 112 (5.6) | ||

| Anxiety case | 61 (3.0) | 149 (7.4) | < 0.01 | 0.06 | ||

| FIT screening | Before screening | Non anxiety | 1977 (82.0) | 138 (5.7) | ||

| Anxiety case | 103 (4.3) | 194 (8.0) | 0.08 | 0.32 | ||

| Positive screening result | Before screening | Non anxiety | 292 (84.0) | 16 (4.6) | ||

| Anxiety case | 11 (3.2) | 28 (8.2) | 0.49 | 0.58 | ||

| Negative screening result | Before screening | Non anxiety | 3368 (82.8) | 234 (5.7) | ||

| Anxiety case | 153 (3.8) | 315 (7.7) | < 0.01 | 0.11 | ||

None of the statistically significant mean changes observed fulfilled the criteria of a clinically relevant change (= change of ½ SD or Cohen’s d of 0.5).

This is the first randomized study to measure the long-term changes in anxiety from before CRC screening to one year after screening and to compare these changes with those of a control group. No clinically relevant change in anxiety, depression or HRQOL was documented in individuals receiving a positive CRC screening result one year after invitation to participate. Participants who received negative screening results reported decreased anxiety and improved HRQOL, but this effect was temporary and not clinically relevant. No clinically relevant psychological effects were observed in relation to FIT participation. In contrast, FS screening participants showed a marginally significant higher probability of being an anxiety case one year after screening compared to controls. The FS participants who progressed from not having anxiety to being considered an anxiety case showed a high anxiety level at baseline. Overall, for the vast majority, there were no clinically relevant psychological effects of participation in CRC screening, while for a small group of people, FS screening caused anxiety.

The results of the few previous studies on the psychological effects of CRC screening are inconsistent. Some studies find no effects of positive screening results on long-term general anxiety[6,10,12] or on HRQOL[11], consistent with our results. Another study by Bobridge et al[8] documents higher anxiety in participants with positive compared to negative FIT results. However, due to comorbidities, these groups may differ prior to screening. For example, individuals experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms, such as anal fistula, are more likely both to have a false-positive FOBT and to be anxious[26,27]. Consequently, the sample of participants receiving positive screening results is not necessarily comparable to those with a negative test, making within-participant measurements necessary. Furthermore, neither the effects documented in Bobridge’s study[8], or the mean changes observed in our study, fulfill the criteria for a clinically relevant change (of ½ SD[24]). Thus, there is little evidence for the concern that receiving a positive primary CRC screening result causes clinically relevant long-term anxiety.

In the present study, we observed a greater increase in the number of cases of anxiety in the FS screening group compared to the changes in the control group. Only one previous study has compared the psychosocial changes in CRC screening participants with a group not offered screening[12]. That study reported no increased anxiety in screening participants. The colonoscopy participants in that study were informed that their whole bowel had been visualized and that their risk of CRC was low, while our FS participants were informed that their whole bowel had not been visualized, which might have caused more insecurity. Importantly, the study mentioned above did not document within-group changes from before to after screening.

It would be interesting to compare psychological effects of colonoscopy screening with changes observed in the two screening modalities in the current study. However, because this is a pilot for a national CRC screening programme in Norway, it was decided to only include modalities with proven effect on CRC mortality in randomized controlled trials (RCT). Both FS and FIT meets this requirement[2], while there are no results from RCT on colonoscopy screening available yet. As a consequence, no participants were invited to colonoscopy screening as a primary screening test in the BCSN pilot study.

In this study, FS screening was associated with an increase in cases of anxiety. One explanation of this finding could be that the participants who were referred to surveillance colonoscopies were the ones who become anxious, as they were awaiting further examinations. However, the results remained the same when we excluded these participants, and previous research shows no negative psychological effects of being offered surveillance colonoscopies[28,29]. While an increase in anxiety was observed among FS participants, there was no significant psychological effect of FIT screening. Invasive procedures are known to be associated with more anxiety[30]. Furthermore, FS differs from other screening procedures in that participants can follow the examination and observe any polyps. How participants interpret the presence of a polyp remains unclear, but this process can cause worries[28]. There are individual differences in how individuals process information about own health, and these differences influence the impact of the information received[31,32]. In our study, participants who progressed from being classified as a non-anxiety case to a case of anxiety in the year following FS participation had a higher anxiety level prior to screening compared to the other screening participants. People with high self-rated anxiety can have cognitive biases, causing them to devote more attention to dangerous stimuli (such as cancers and an invitation to participate in a screening program due to being in a high-risk group) and to interpret mild threats as highly threatening[33]. This bias has been found to increase anxiety levels[34]. Further, anxious participants have a greater fear of cancer[35] and a higher perceived risk of developing CRC[36], both of which are associated with higher anxiety in screening[37,38]. Future research should replicate our findings and investigate how anxious people might perceive screening as less distressing.

We observe no effect of FIT screening participation on anxiety, short- or long term. However, for FS screening we observe increased long-term anxiety in a sub-group, but there was no short-term effect[16]. One possible explanation is that the depth of peoples information processing depend on their emotional states[39]. Most people will have a negative screening result, and people experience positive emotions and relief after FS examination[12,31]. Positive emotion cause simple information processing, meaning that individuals think in terms of cancer or no cancer, and are relieved as they have not received a diagnosis of cancer. However, once the positive emotions disappear, individuals may process their screening experience deliberately. Individuals anxious about own health are especially likely to do so, because they are not reassured by CRC screening[31]. For example, they may process the presence and removal of polyps. Participants with negative screening results may focus on the fact that the whole bowel has not been visualized in the sigmoidoscopy examination, and consequently they did not receive the “all clear” result they may have expected. Some individuals who had all visible polyps removed during colonoscopy may be afraid that new polyps can develop. To individuals with high anxiety levels these health threats may be perceived as very threatening.

Previous research has reported decreased anxiety and improvements in HRQOL after receiving a negative CRC screening result[12,16,40-42], in congruence with our results. The decreased anxiety might result from a decreased perceived risk of CRC, which could reduce motivation to maintain a healthy lifestyle. However, our results show that the decreased anxiety is temporary, disappearing within 1 year. This is reassuring, as short-term relief is less likely to create lasting health behavioral changes.

We used the HADS, a generic measure of anxiety, to identify psychiatric morbidity. However, a large meta-analysis of breast cancer screening showed that false-positive mammograms have negative effects on participants when measured by screening-specific measures, but not by generic measures[43]. In order to investigate the potential harms of screening programs, it is important to document whether screening causes psychiatric morbidity, as well as screening-specific anxiety. Therefore, future research should replicate our study, using a cancer-specific anxiety measure, in order to get a complete understanding of the psychological effects of CRC screening.

Due to the prospective design of the current study, the number of participants who received a positive screening result was low, limiting our ability to detect statistically significant effects. The low response rate might limit the generalizability of our results. CRC screening attenders are more often married[44], have a higher socioeconomic status[45] and better mental health[46] compared to non-attendees. Consequently, individuals who differ on these characteristics might respond differently towards screening attendance compared to our participants.

Participation in screening might be perceived as a benefit to the invited individuals. Selection bias in screening attendance might therefore differ from the determinants of compliance in the control group, which presented no immediate benefit to participants. However, the FS group and control group were similar in demographic variables, anxiety, depression and HRQOL prior to screening. Furthermore, the screening group and control group showed a similar change in depression and HRQOL over 1 year. We therefore believe that the greater increase in cases of anxiety in the FS compared to the control group was due to screening participation.

In conclusion, this study found no clinically relevant psychological harm of receiving a positive CRC screening result one year after invitation to undergo screening. FS screening participants, but not FIT participants, showed a marginally significant higher probability of having clinically meaningful anxiety one year after screening compared to controls. Thus, most participants who attend CRC screening do not experience clinically relevant long-term effects on anxiety, depression and HRQOL over one year. However, for a smaller, possibly anxious group, participation in FS screening may cause anxiety.

We would like to thank Anita Jørgensen, Benedicte Sofie Eilertsen, Jan Inge Nordby, Jakob Katkjær and the devoted doctors and nurses at Bærum Hospital and Østfold Hospital: Anna Lisa Schult, Helge Evensen, Tone Lise Åvitsland, Øystein Rose, Senaria Matapour, Jens Aksel Nilsen, Silje Hugin, Ole Darre-Næss, Svein-Oskar Frigstad, Marius Vinje, Kristine Wiencke, Jonas Koch, Hanne Margit Mårdalen, Charlotte Noordhof, Joakim Magnussen, Hege Marie Svendsen, Elin Rogn Andersen, Maria Rusten Ringstad, Torun Dyrkorn, Trine Horn, Isa Lind, Monica Korsmo Sand, Isobel O’Gorman Arntzen, Kristine Melbye Kolbjørnsen, Ida Jeanette Lauritsen, Nina Stø Skukkestad, Heidi Lillian Solberg, Ann Kristin Aarum, Nina Fladeby, Bjørg Jankila, Nina Sivertsen Larsen, Stine Langbråten, Katrine Romstad, Kristin Ranheim Randel, Dung Hong Nguyen, Alvilde Ossum, Elisabeth Haagensen Gulichsen, Marie Ek Olsen, Eirin Dalén, Mobina Nawaz, Øyvind Glåmseter, Per Kristian Sandvei, Taran Søberg, Frode Lerang, Magne Henriksen, Tanja Owen, Robin Holt Paulsen, Erik Christensen and Rogelio Barreto.

Screening invites initially healthy people to be screened for cancer. The majority of participants will never develop cancer but might experience psychological stress from participation in the screening programme. It is important to determine the benefits and harms of screening.

The present study aimed to investigate possible long-term psychological harm of participation in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in Norway. Participants are invited to flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) screening or fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

The results from previous research on psychological effects of CRC screening are inconsistent. While recommendations for psychosocial studies of screening recommend use of baseline and follow-up measures, and comparison to control groups, no study have investigated changes in anxiety from before CRC screening to after screening, and compared these changes to changes in a group not offered screening. This study is the first to do that, and the results show that participating in screening have no psychological effect on most participants, while FS screening cause increased anxiety in some participants. Participants with high levels of anxiety before screening might be vulnerable to get anxious from FS screening.

It is important to understand benefit and harms of a screening programme, as more countries are considering implementation of CRC screening. Further research should focus on how to reduce anxiety in participants vulnerable to experience increased anxiety in FS screening.

The paper is about the long-term psychological harm of participation in CRC screening in Norway. An interesting paper on the attitudes towards CRC screening that can help in designing future screening programs. Further research is still needed to find a definitive answer.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Norway

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lakatos PL, Riss S, Verma M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21450] [Article Influence: 1950.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Holme Ø, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Hoff G. Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD009259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Holme Ø, Løberg M, Kalager M, Bretthauer M, Hernán MA, Aas E, Eide TJ, Skovlund E, Schneede J, Tveit KM, Hoff G. Effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:606-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1624-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1242] [Cited by in RCA: 1155] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Laing SS, Bogart A, Chubak J, Fuller S, Green BB. Psychological distress after a positive fecal occult blood test result among members of an integrated healthcare delivery system. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brasso K, Ladelund S, Frederiksen BL, Jørgensen T. Psychological distress following fecal occult blood test in colorectal cancer screening--a population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1211-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Denters MJ, Deutekom M, Essink-Bot ML, Bossuyt PM, Fockens P, Dekker E. FIT false-positives in colorectal cancer screening experience psychological distress up to 6 weeks after colonoscopy. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2809-2815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bobridge A, Bampton P, Cole S, Lewis H, Young G. The psychological impact of participating in colorectal cancer screening by faecal immuno-chemical testing--the Australian experience. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:970-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Parker MA, Robinson MH, Scholefield JH, Hardcastle JD. Psychiatric morbidity and screening for colorectal cancer. J Med Screen. 2002;9:7-10. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kapidzic A, Korfage IJ, van Dam L, van Roon AH, Reijerink JC, Zauber AG, van Ballegooijen M, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME. Quality of life in participants of a CRC screening program. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1295-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Taylor KL, Shelby R, Gelmann E, McGuire C. Quality of life and trial adherence among participants in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1083-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thiis-Evensen E, Wilhelmsen I, Hoff GS, Blomhoff S, Sauar J. The psychologic effect of attending a screening program for colorectal polyps. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:103-109. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bray F, Wibe A, Dørum LM, Møller B. [Epidemiology of colorectal cancer in Norway]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2007;127:2682-2687. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bretthauer M, Ekbom A, Malila N, Stefansson T, Fischer A, Hoff G, Weiderpass E, Tretli S, Trygvadottir L, Storm H. [Politics and science in colorectal cancer screening]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2006;126:1766-1767. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bretthauer M, Hoff G. Comparative effectiveness research in cancer screening programmes. BMJ. 2012;344:e2864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kirkøen B, Berstad P, Botteri E, Åvitsland TL, Ossum AM, de Lange T, Hoff G, Bernklev T. Do no harm: no psychological harm from colorectal cancer screening. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:497-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl AA. Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:540-544. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Loge JH, Kaasa S, Hjermstad MJ, Kvien TK. Translation and performance of the Norwegian SF-36 Health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. I. Data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1069-1076. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Loge JH, Kaasa S. Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey: normative data from the general Norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med. 1998;26:250-258. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220-233. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ware J, Kosinski M. Physical and mental health summary scales: A manual for users of Version 1. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric. Inc 2001; . |

| 23. | Olssøn I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale: a cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2181] [Cited by in RCA: 3455] [Article Influence: 150.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press 1969; . |

| 26. | Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Are anxiety and depression related to gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:294-298. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Cioli VM, Gagliardi G, Pescatori M. Psychological stress in patients with anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Miles A, Atkin WS, Kralj-Hans I, Wardle J. The psychological impact of being offered surveillance colonoscopy following attendance at colorectal screening using flexible sigmoidoscopy. J Med Screen. 2009;16:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liljegren A, Lindgren G, Brandberg Y, Rotstein S, Nilsson B, Hatschek T, Jaramillo E, Lindblom A. Individuals with an increased risk of colorectal cancer: perceived benefits and psychological aspects of surveillance by means of regular colonoscopies. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1736-1742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Weller A, Hener T. Invasiveness of medical procedures and state anxiety in women. Behav Med. 1993;19:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Miles A, Wardle J. Adverse psychological outcomes in colorectal cancer screening: does health anxiety play a role? Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1117-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Williams-Piehota P, Schneider TR, Pizarro J, Mowad L, Salovey P. Matching health messages to information-processing styles: need for cognition and mammography utilization. Health Commun. 2003;15:375-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:1-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2300] [Cited by in RCA: 2453] [Article Influence: 129.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mathews A, MacLeod C. Induced processing biases have causal effects on anxiety. Cogn Emot. 2002;16:331-354. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vrinten C, van Jaarsveld CH, Waller J, von Wagner C, Wardle J. The structure and demographic correlates of cancer fear. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Robb KA, Miles A, Wardle J. Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with perceived risk for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:366-372. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Drossaert CH, Boer H, Seydel ER. Monitoring women’s experiences during three rounds of breast cancer screening: results from a longitudinal study. J Med Screen. 2002;9:168-175. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Absetz P, Aro AR, Sutton SR. Experience with breast cancer, pre-screening perceived susceptibility and the psychological impact of screening. Psychooncology. 2003;12:305-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bless H, Bohner G, Schwarz N, Strack F. Mood and Persuasion: A Cognitive Response Analysis. Person Soc Psychol Bull. 1990;16:331-345. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wardle J, Williamson S, Sutton S, Biran A, McCaffery K, Cuzick J, Atkin W. Psychological impact of colorectal cancer screening. Health Psychol. 2003;22:54-59. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Taupin D, Chambers SL, Corbett M, Shadbolt B. Colonoscopic screening for colorectal cancer improves quality of life measures: a population-based screening study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Pizzo E, Pezzoli A, Stockbrugger R, Bracci E, Vagnoni E, Gullini S. Screenee perception and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer screening: a review. Value Health. 2011;14:152-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Salz T, Richman AR, Brewer NT. Meta-analyses of the effect of false-positive mammograms on generic and specific psychosocial outcomes. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1026-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | van Jaarsveld CH, Miles A, Edwards R, Wardle J. Marriage and cancer prevention: does marital status and inviting both spouses together influence colorectal cancer screening participation? J Med Screen. 2006;13:172-176. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Pornet C, Dejardin O, Morlais F, Bouvier V, Launoy G. Socioeconomic determinants for compliance to colorectal cancer screening. A multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Kodl MM, Powell AA, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Bangerter AK, Partin MR. Mental health, frequency of healthcare visits, and colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2010;48:934-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |