Published online Sep 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7841

Peer-review started: March 29, 2016

First decision: May 27, 2016

Revised: July 2, 2016

Accepted: August 1, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: September 14, 2016

Processing time: 165 Days and 1 Hours

To investigate the efficacy of double-layered covered stent in the treatment of malignant oesophageal obstructions.

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed following the PRISMA process. PubMed (Medline), EMBASE (Excerpta Medical Database), AMED (Allied and Complementary medicine Database), Scopus and online content, were searched for studies reporting on the NiTi-S polyurethane-covered double oesophageal stent for the treatment of malignant dysphagia. Weighted pooled outcomes were synthesized with a random effects model to account for clinical heterogeneity. All studies reporting the outcome of palliative management of dysphagia due to histologically confirmed malignant oesophageal obstruction using double-layered covered nitinol stent were included. The level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Six clinical studies comprising 250 patients in total were identified. Pooled technical success of stent insertion was 97.2% (95%CI: 94.8%-98.9%; I2 = 5.8%). Pooled complication rate was 27.6% (95%CI: 20.7%-35.2%; I2 = 41.9%). Weighted improvement of dysphagia on a scale of 0-5 scoring system was -2.00 [95%CI: -2.29%-(-1.72%); I2 = 87%]. Distal stent migration was documented in 10 out of the 250 cases examined. Pooled stent migration rate was 4.7% (95%CI: 2.5%-7.7%; I2 = 0%). Finally, tumour overgrowth was reported in 34 out of the 250 cases with pooled rate of tumour overgrowth of 11.2% (95%CI: 3.7%-22.1%; I2 = 82.2%). No funnel plot asymmetry to suggest publication bias (bias = 0.39, P = 0.78). In the sensitivity analysis all results were largely similar between the fixed and random effects models.

The double-layered nitinol stent provides immediate relief of malignant dysphagia with low rates of stent migration and tumour overgrowth

Core tip: The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to investigate the efficacy of double-layered nitinol covered stent in the treatment of malignant oesophageal obstructions. The literature was searched following the PRISMA selection process as recommended by Cochrane. Weighted pooled outcomes were synthesized with a random effects model to account for clinical heterogeneity. This meta-analysis highlights the promising outcomes of the double-layered covered stent and demonstrates significant immediate relief of dysphagia with low rates of stent migration and tumour overgrowth. The unique design of this stent seems to combines the merits of both plain covered and uncovered metal esophageal stent designs.

- Citation: Hussain Z, Diamantopoulos A, Krokidis M, Katsanos K. Double-layered covered stent for the treatment of malignant oesophageal obstructions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(34): 7841-7850

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i34/7841.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7841

Oesophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Despite the significant advances in diagnostic and therapeutic options, the 5-year survival rate remains remarkably low[1]. More than 50% of patients present late and are deemed unsuitable for surgical resection[2,3]. The lack of early warning signs and symptoms means that patients usually become symptomatic in an advanced stage of the disease. In addition, esophageal cancer usually affects elderly patients who suffer from multiple co-morbidities. Both these factors render affected patients poor surgical candidates[1,2,4]. The most important complaint of these patients is the tumour related dysphagia resulting in poor oral intake and malnutrition.

Palliative treatment options of malignant dysphagia include balloon dilatation, laser ablation, sclerotherapy, thermal coagulation, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and endoscopically and/or fluoroscopically guided stent placement across the obstruction. Nowadays, the placement of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is considered the treatment of choice for malignant dysphasia, given the quick and effective symptomatic relief and its ease of use and relative safety[2,3,5]. Stents used in for the treatment of malignant esophageal obstruction can be either covered or uncovered[6-9].

One of the more widely used SEMS today is the double-layered covered nitinol stent (NiTi-S, Taewoong Medical, South Korea) which was designed to combine the advantageous characteristics of covered stents that prevent tissue ingrowth and re-obstruction, and uncovered stents that have demonstrated lower rates of migration. The authors performed a systematic review of the literature in order to assess the clinical outcomes of this double-layered covered nitinol stent in the treatment of malignant esophageal obstruction with a focus on stent insertion success, peri-procedural complications, relief of dysphagia, and stent failure because of migration or tumour overgrowth.

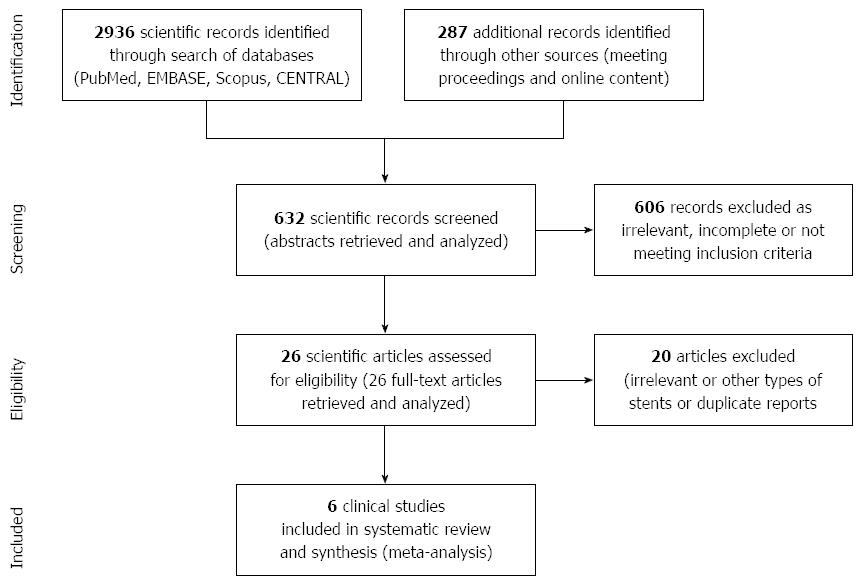

The literature was searched following the PRISMA selection process as recommended by Cochrane. PubMed (Medline, 1950 to present), EMBASE (Excerpta Medical Database, 1980 to present), AMED (Allied and Complementary Database, 1985 to present), Scopus (1970 to present) and the CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) were searched. The search terms used were “oesophageal” or “stent” or “double-covered” or “NiTi-S” and “trial” or “study” or “controlled trial”, as well as the relevant terms and corresponding Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH). The search was last updated on 31 January 2016. There were no language restrictions. Papers of all relevant published studies identified from the above search strategy were obtained and assessed for potential eligibility independently by two of the senior authors (AD and KK).

All studies reporting the outcome of palliative management of dysphasia due to histologically confirmed malignant oesophageal stricture/obstruction in adult patients, by insertion of a double-layered covered nitinol stent were included in the present meta-analysis. There was no intention of future resection or surgery in all included patients due to locally advanced disease, distant metastasis or serious co-morbidities precluding surgical management. Stent placement was performed either under fluoroscopy or endoscopic guidance.

Papers reporting the management of oesophageal strictures due to benign disease, anastomotic strictures and stents inserted as a bridge to surgery or prior to radical radiotherapy were excluded from this study. Studies reporting the outcomes of stents other than the double-layered covered NiTi-S stent were also excluded.

Data were extracted by the same two authors independently. Descriptive data including baseline demographics, follow-up periods and primary and secondary outcome measures were collected. Outcome measures were defined according to the previously published International guidelines. These included immediate technical success of stent insertion, peri-procedure complication rates, reported dysphagia improvement, and rates of stent migration and tumour overgrowth during follow-up. The same dysphagia scoring system was used in all papers as follows: score 0, normal diet; score 1, able to eat some solid food; score 2, able to eat some semi-solids only; score 3, liquids only; and score 4, complete inability to swallow[10]. Data were extracted from the main text and tables of the published papers. In case of missing data, relevant abstracts and presentations from annual meetings proceedings were analysed and/or the corresponding authors were contacted. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus between the investigators.

The double-layered covered nitinol stent (NiTi-S, Taewoong Medical, Seoul, South Korea) has a double-layer configuration, consisting of an inner “dog-bone” nitinol stent (nickel-titanium thermal memory allow) that is fully covered with polyurethane layer and an outer uncovered nitinol wire mesh designed to prevent or reduce stent migration by allowing tumour in-growth and anchorage at the tumour site[11]. When delivered, the stent flares at its proximal and distal ends. A thread is attached inside the proximal flange of the stent, when being pulled; the thread reduces the diameter of the stent, enabling stent repositioning or removal. The Niti-S stent shortens approximately 35% after placement, therefore, a stent measuring 2 to 4 cm longer than the stricture is usually used to allow for a 1- to 2-cm extension above and below the proximal and distal components of the tumour. The stent is delivered in a compressed form inside an introducer sheath under fluoroscopic or endoscopic guidance.

Quantitative data synthesis of all included studies was created/performed using Statsdirect software (Version 2.7.9, Statsdirect Ltd, Chechire, United Kingdom). Categorical variables were expressed in percentages and continuous variables in mean ± SD if normally distributed. Summary statistics of the primary and secondary endpoint measures were expressed as weighted proportional outcomes and the associated 95%CIs. The random DerSimonian and Laird (D-L) effects model was applied to calculate the pooled proportional outcomes. We also performed a sensitivity analysis with the inverse variance fixed effects model. Cochran’s Q (χ2) test and I2 statistic were used to test for statistical evidence of heterogeneity (non-combinability of studies) across the included studies. An I2 value of less than 25% indicates low heterogeneity, while values between 25% and 50% and values of more than 50% indicate moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. Potential publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of inverted funnel plot asymmetry as recommended for systematic reviews and meta-analyses including a small number of studies. The Horbold-Egger test was also used to indicate publication bias in case of subjective funnel plot evaluation. The level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

A total of 6 articles meeting the inclusions criteria of this study were identified with the PRISMA selection process (Figure 1) including 5 single-arm cohort studies and 1 randomized controlled trial[11-16]. Clinical details of a total of 250 patients (206 male), median age is 68 (range: 42-84), who underwent palliative stent insertion for malignant oesophageal obstruction over a period of 10 years (January 2006-January 2016) were obtained and pooled for the purposes of this analysis. The median follow-up period ranged between 2 mo (62 d) and 6 mo[11-16]. Two studies reported comparisons between different stents (single and double-layered stents)[12,13], but we extracted and pooled only the double-layered ones for the purposes of the meta-analysis. Histology of treated tumours was balanced between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma and nearly half of the cases involved the distal oesophagus. A summary of characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis is shown in Table 1.

| Publication | Study design | Sample (n) | Age (yr) | Male gender | Adenocarcinoma | Distal esophagus | Tumour length (cm) |

| Verschuur et al[16], 2006 | Prospective | 42 | 65 ± 14 | 60% | 76% | 21% | 7.8 ± 2.4 |

| cohort | |||||||

| Kim et al[13], 2009 | Prospective | 17 | 68 ± 8 | 94% | 33% | 39% | 6.1 ± 2.6 |

| randomized | |||||||

| Park et al[15], 2010 | Prospective | 32 | 67 ± 9 | 75% | N/A | 53% | N/A |

| cohort | |||||||

| Battersby et al[12], 2012 | Prospective | 55 | 72 | 67% | 56% | 93% | 11.7 ± 2.5 |

| cohort | (stent length) | ||||||

| Kim et al[14], 2012 | Prospective | 48 | 68 ± 11 | 81% | 33% | 37% | N/A |

| cohort | |||||||

| Mezes et al[11], 2014 | Retrospective | 56 | N/A | 61% | 38% | 55% | N/A |

| cohort |

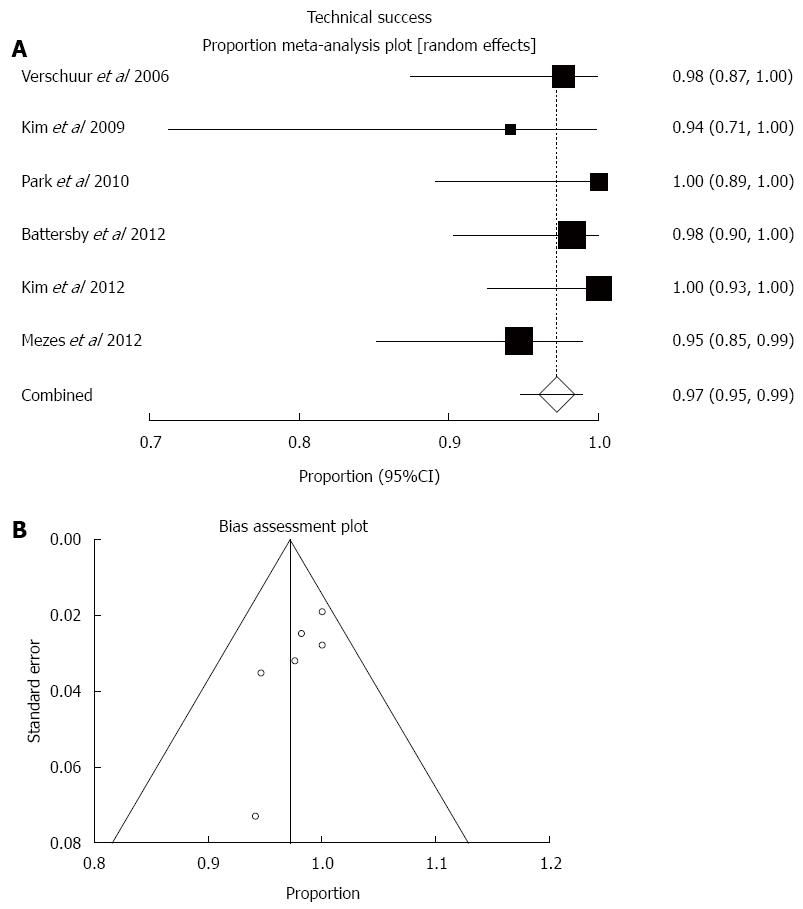

Predefined outcome measures were reported in all 6 included studies. Successful stent insertion was reported in 244 out of the 250 cases. The pooled technical success rate (weighted proportion) was 97.2% (95%CI: 94.8%-98.9%; Figure 2). There was low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 5.8%, P = 0.38) and no visual asymmetry of the respective funnel plot to suggest publication bias (bias = -1.48, P = 0.08).

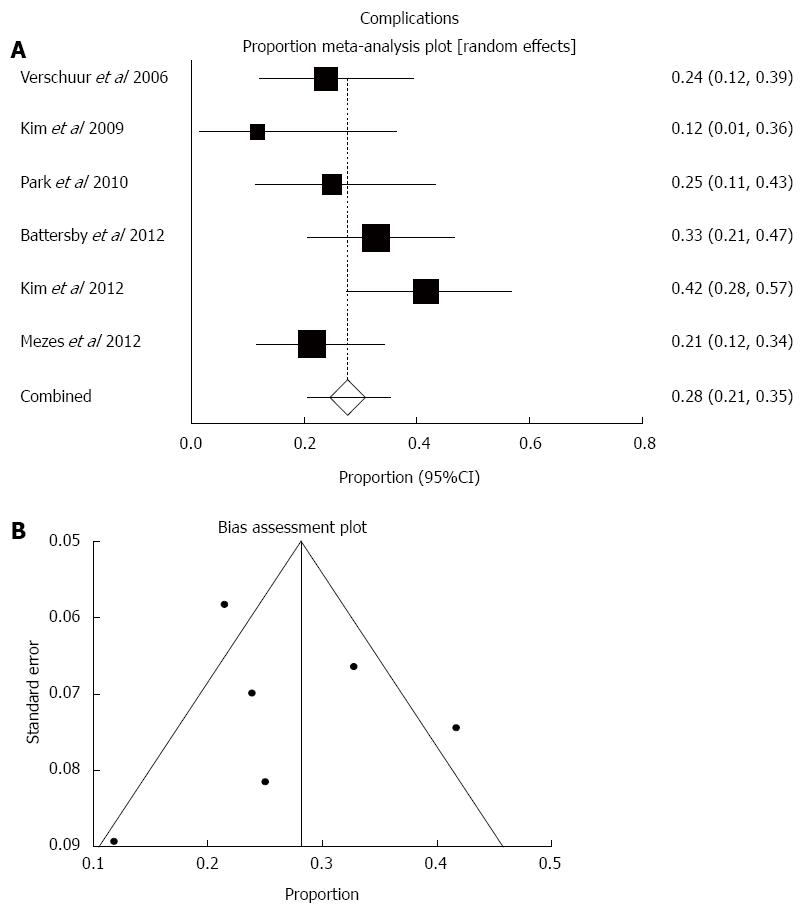

Complications were reported in 70 out of the 250 cases. Most often encountered complications were reflux esophagitis and aspiration pneumonia, whereas oesophageal fistula was rarely noted (Table 2). Pooled complication rate was 27.6% (95%CI: 20.7%-35.2%; Figure 3). There was moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 41.9%, P = 0.13) and no funnel plot asymmetry to suggest publication bias (bias = -1.21, P = 0.79).

| Publication | Tumour overgrowth | Stent migration | Food impaction | Reflux esophagitis | Aspiration pneumonia | Esophageal fistula | Perforation | Hemorrhage |

| Verschuur et al[16], 2006 | n = 2 | n = 3 | - | n = 2 | n = 2 | - | n = 1 | n = 1 |

| Kim et al[13], 2009 | - | - | n = 1 | - | - | n = 1 | - | - |

| Park et al[15], 2010 | n = 5 | n = 1 | - | n = 4 | n = 1 | n = 1 | - | - |

| Battersby et al[12], 2012 | n = 1 | n = 3 | 6% | 8% | 3% | 0.8% | 0.4% | - |

| Kim et al[14], 2012 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 2 | n = 13 | n = 5 | n = 2 | - | - |

| Mezes et al[11], 2014 | n = 19 | n = 4 | - | - | - | n = 1 | - | - |

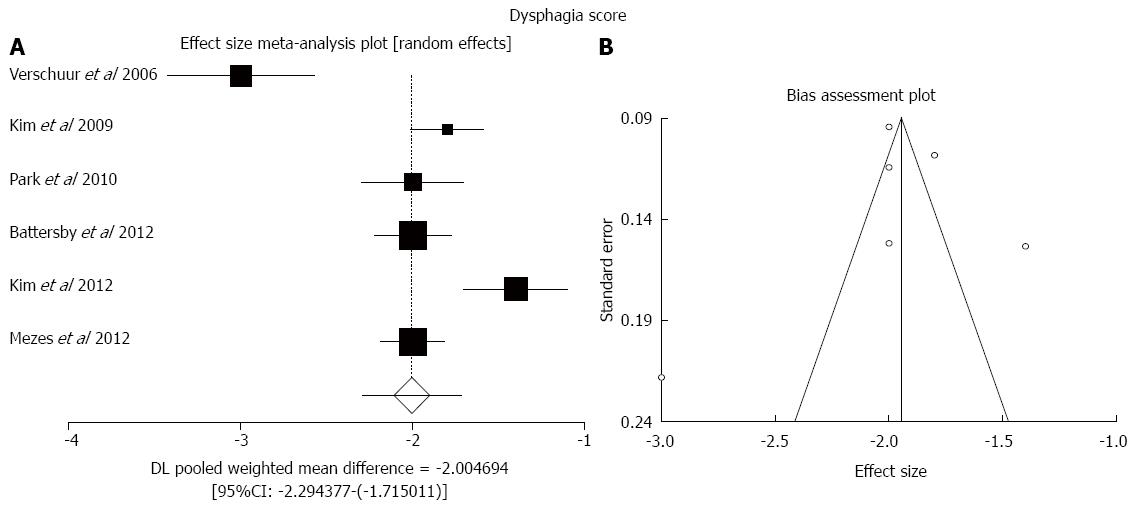

Pooled improvement in dysphagia score (weighted score reduction compared to baseline) was -2.00 [95%CI: -2.29-(-1.72); Figure 4]. There was high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 87%, P < 0.0001) and no evidence of publication bias (bias = -3.79, P = 0.46).

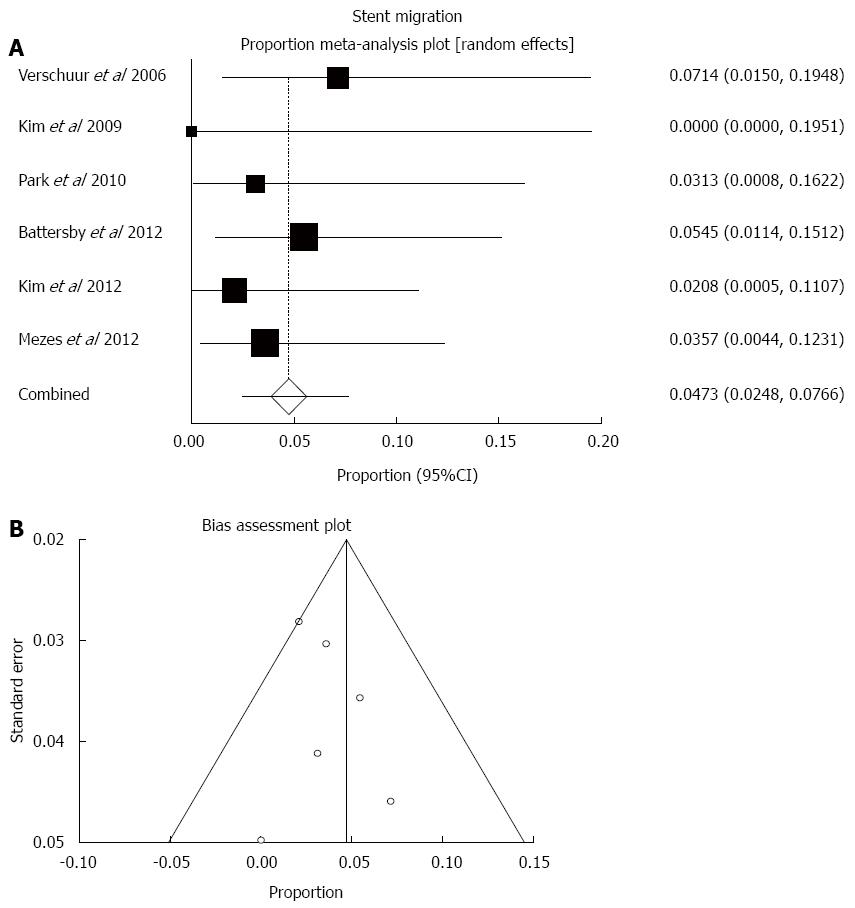

Distal stent migration was documented in 10 out of the 250 cases examined. Pooled stent migration rate was 4.7% (95%CI: 2.5%-7.7%; Figure 5). There was very low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.82) and no funnel plot asymmetry to suggest publication bias (bias = 0.39, P = 0.78).

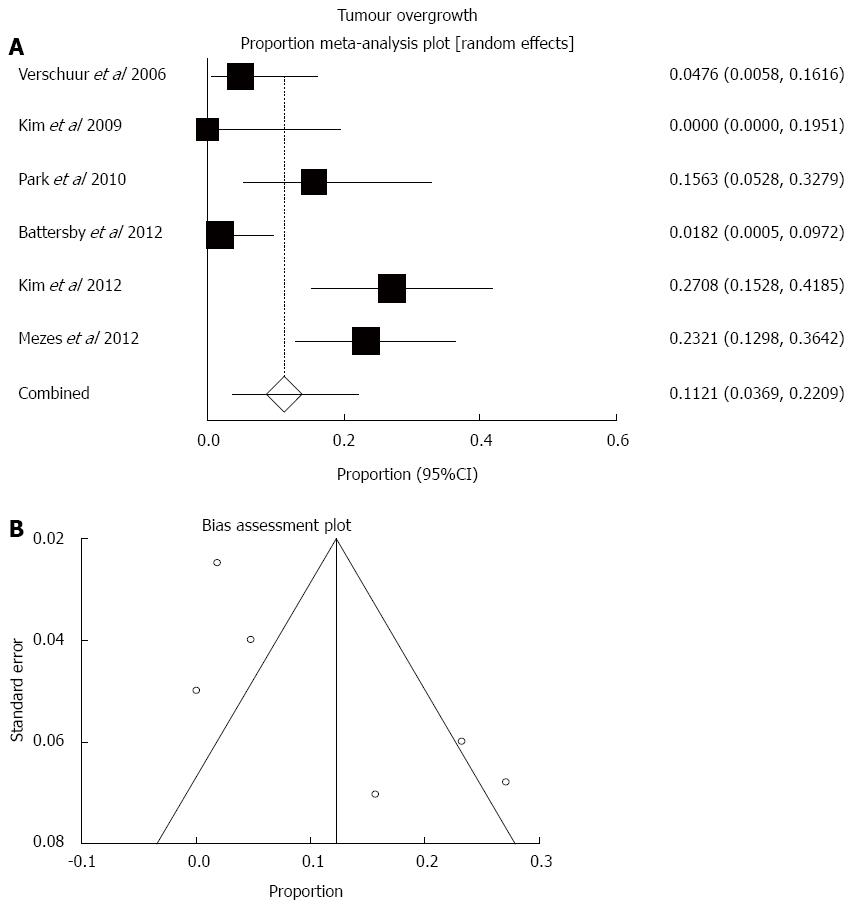

Finally, tumour overgrowth was reported in 34 out of the 250 cases in total. Pooled overgrowth rate was 11.2% (95%CI: 3.7%-22.1%; Figure 6). There was high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 82.2%, P < 0.0001) and some funnel plot asymmetry suggestive of potential publication bias (bias = 4.13, P = 0.06).

In the sensitivity analysis all results were largely similar between the fixed and random effects models as summarised in Table 3.

| Parameters | Pooled estimates Random (95%CI) | Pooled estimates Fixed (95%CI) | I² heterogeneity |

| Technical success (%) | 97.2 (94.8-98.9) | 97.2 (94.9-98.9) | Low (5.8%) |

| Overall complications (%) | 27.6 (20.7-35.2) | 28.1 (22.8-33.8) | Moderate (41.9%) |

| Dysphagia score improvement (0-4) | -2.00 [-2.29-(-1.72)] | -1.94 [-2.04-(-1.84)] | High (87.0%) |

| Migration (%) | 4.7 (2.5–7.7) | 4.7 (2.5–7.7) | Low (0.0%) |

| Overgrowth (%) | 11.2 (3.7–22.1) | 12.3 (8.5–16.6) | High (82.2%) |

The use of SEMS is a well-established palliative management of the dysphagia associated with advanced oesophageal malignancy, but the optimal stent design is still debated[2,7,17]. Stents used in the treatment of oesophageal obstruction are made of stainless steel, nitinol or plastic stents and they can be either covered or uncovered[2-5]. Previous covered plastic stents have now been largely replaced with metal stent which provide safe, rapid and effective symptomatic relief with fewer complications. Covering of metal struts with polyethylene, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), silicone or polyurethane coating is believed to reduce the rate of re-obstruction due to tissue ingrowth/overgrowth compared to the uncovered ones[6-9], however, they are implicated in higher rates of migration[2]. Newer commercially available stent options include biodegradable oesophageal stents and intraluminal radioactive stents[18,19].

Newer stents are constructed from nitinol, which has the advantage of thermal memory and can conform to a more predicable self-expanding shape after deployment compared to older metal stents made from stainless steel[2,8,19]. The new type of double-layered nitinol stent is believed to combine the merits of both covered and uncovered stents. Its inner layer is covered with polyurethane material to prevent tumour encroachment, while the outer layer consists of an uncovered metal mesh to prevent or reduce migration by being implanted into tumour tissue or oesophageal wall[11-16]. The present meta-analysis has demonstrated a high pooled success of stent insertion (> 97%) with acceptable rates of procedure-related complications. The latter were encountered in a quarter of the cases (27.6%) and seem to be in line with the usually encountered complications during oesophageal stent insertion for palliation of cancer-related dysphagia[2,4,12]. Most importantly, significant relief of dysphagia was found that was 2 points on average out of the 0-4 dysphagia scale. This is very important to help restore oral intake and treat poor nutrition that has been found to be associated with poorer long-term survival outcomes[11]. Furthermore, the double-layered covered Niti-S stent was found to be related to quite low incidence of stent migration and late tumour overgrowth compared to historical outcomes of uncovered or single-covered stents[2,3].

The most frequent early and late complication of oesophageal SEMS is stent malfunction or failure, either due to migration (i.e., slipping distally into the stomach or small bowel), or tissue ingrowth/overgrowth or less frequently food impaction that leads to recurrent dysphagia. The pooled estimate of migration rate in this analysis was 4.7%, which on one hand is significantly lower than the so far reported migration rates of covered stents that range between 25%-32%, and on the other hand appears to be very similar to the reported migration rates of uncovered stents[2]. Stent migration will present with early recurrent dysphagia and may be easily treated with endoscopic retrieval of the migrated stent followed by repeat insertion of another one, or may develop to more serious small bowel obstruction mandating open laparotomy that entails a risk of death in the setting of advanced oesophageal cancer[12]. Symptomatic tumour overgrowth at the stent edge was found to affect nearly 1 in 10 of the analysed cases and can be easily treated with repeat co-axial insertion of another covered stent. Stent failure/blockage because of food impaction was rarely reported and is a more benign complication that may be treated with endoscopic clearance of the clogged debris and encouragement of fizzy drinks[2,3].

Other frequently reported complications of the double-layered PTFE-covered Nitinol stent include reflux esophagitis, most commonly associated with lower oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) tumours and the infrequent but life threatening aspiration pneumonia and tracheo-oesophageal fistula. Hence, prescription of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) is recommended in all cases of covered stent placement across the GOJ. The proposed mechanism of fistula formation after stent placement is pressure necrosis of the tumour and oesophageal wall or trauma from the sharp stent ends on the oesophageal mucosa[12]. This complication has been treated successfully with a second overlapping covered stent into the first stent[20]. Other rarely reported complications may include haemorrhage and oesophageal perforation because of poor operative technique and/or local tumour infiltration.

The main limitation of this meta-analysis is the small number of studies identified, and subsequently, the relatively small number of total patients included in the analysis. There was some between-trials heterogeneity that may compromise internal validity, but there was good agreement between the random and fixed effects models that underlines the external validity of our results. In addition, with the exception of 1 randomized design, no comparative studies were available to allow comparison of different stent designs. The number of trials and sample size were too small to support further subgroup comparisons or other regression analyses.

The data compiled in this meta-analysis highlight the promising outcomes of the double-layered polyurethane covered NiTi-S stent in the treatment of esophageal obstruction secondary to malignancy with significant immediate relief of dysphagia and low rates of stent migration and tumour overgrowth. Despite the inherent limitations of this study, the present data suggests that patients are likely to benefit from the unique design of this stent which seems to have low migration rate, comparable to that of uncovered stent, while maintaining the lower rate of re-obstruction due to tissue ingrowth/overgrowth seen in plain covered stents[12]. The authors of this study therefore believe that the double-layered covered nitinol stent combines the merits of both plain covered and uncovered metal esophageal stent designs.

Esophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. More than 50% of patients present late and are deemed unsuitable for surgical resection. The most important complaint of these patients is the tumour related dysphagia resulting in poor oral intake and malnutrition. Nowadays, the placement of self-expanding metal stents is considered the treatment of choice for malignant dysphasia given the quick and effective symptomatic relief and its ease of use and relative safety.

Stents used in the treatment of oesophageal obstruction are made of stainless steel, nitinol or plastic stents and they can be either covered or uncovered. Previous covered plastic stents have now been largely replaced with metal stents which provide safe, rapid and effective symptomatic relief with fewer complications. Covering of metal struts is believed to reduce the rate of re-obstruction compared to the uncovered ones, however, they are implicated in higher rates of migration. Newer stents are constructed from nitinol, which has the advantage of thermal memory and can conform to a more predicable self-expanding shape after deployment. The new type of double-layered nitinol stent is believed to combine the merits of both covered and uncovered stents.

This is the first systematic review of the literature in order to assess the clinical outcomes of this double-layered covered nitinol stent in the treatment of malignant esophageal obstruction with a focus on stent insertion success, peri-procedural complications, relief of dysphagia, and stent failure because of migration or tumour overgrowth.

The data compiled in this meta-analysis highlight the promising outcomes of the double-layered polyurethane covered NiTi-S stent in the treatment of esophageal obstruction secondary to malignancy with significant immediate relief of dysphagia and low rates of stent migration and tumour overgrowth.

This study showed that patients are likely to benefit more from the unique design of this double-layered covered nitinol stent. It is very nicely presented and convincingly shows the very satisfactory outcome following the use of the double covered stent.

| 1. | Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241-2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2115] [Cited by in RCA: 2232] [Article Influence: 97.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Katsanos K, Sabharwal T, Adam A. Stenting of the upper gastrointestinal tract: current status. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:690-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sabharwal T, Morales JP, Irani FG, Adam A; CIRSE: Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. Quality improvement guidelines for placement of esophageal stents. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Katsanos K, Ahmad F, Dourado R, Sabharwal T, Adam A. Interventional radiology in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:1-15. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sabharwal T, Morales JP, Salter R, Adam A. Esophageal cancer: self-expanding metallic stents. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:456-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baerlocher MO, Asch MR, Dixon P, Kortan P, Myers A, Law C. Interdisciplinary Canadian guidelines on the use of metal stents in the gastrointestinal tract for oncological indications. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2008;59:107-122. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Baron TH. Expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1681-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Siersema PD. Treatment options for esophageal strictures. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:142-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Simmons DT, Baron TH. Technology insight: Enteral stenting and new technology. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:365-374; quiz 1 p following 374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ogilvie AL, Dronfield MW, Ferguson R, Atkinson M. Palliative intubation of oesophagogastric neoplasms at fibreoptic endoscopy. Gut. 1982;23:1060-1067. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mezes P, Krokidis ME, Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Sabharwal T, Adam A. Palliation of esophageal cancer with a double-layered covered nitinol stent: long-term outcomes and predictors of stent migration and patient survival. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:1444-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Battersby NJ, Bonney GK, Subar D, Talbot L, Decadt B, Lynch N. Outcomes following oesophageal stent insertion for palliation of malignant strictures: A large single centre series. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim ES, Jeon SW, Park SY, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH. Comparison of double-layered and covered Niti-S stents for palliation of malignant dysphagia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:114-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim MD, Park SB, Kang DH, Lee JH, Choi CW, Kim HW, Chung CU, Jeong YI. Double layered self-expanding metal stents for malignant esophageal obstruction, especially across the gastroesophageal junction. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3732-3737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park JG, Jung GS, Oh KS, Park SJ. Double-layered PTFE-covered nitinol stents: experience in 32 patients with malignant esophageal strictures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:772-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Verschuur EM, Homs MY, Steyerberg EW, Haringsma J, Wahab PJ, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. A new esophageal stent design (Niti-S stent) for the prevention of migration: a prospective study in 42 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:134-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dormann A, Meisner S, Verin N, Wenk Lang A. Self-expanding metal stents for gastroduodenal malignancies: systematic review of their clinical effectiveness. Endoscopy. 2004;36:543-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Zhongmin W, Xunbo H, Jun C, Gang H, Kemin C, Yu L, Fenju L. Intraluminal radioactive stent compared with covered stent alone for the treatment of malignant esophageal stricture. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Parthipun A, Diamantopoulos A, Shaw A, Dourado R, Sabharwal T. Self-expanding metal stents in palliative malignant oesophageal dysplasia. Ann Palliat Med. 2014;3:92-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jung GS, Park SD, Cho YD. Stent-induced esophageal perforation: treatment by means of placing a second stent after removal of the original stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Annese V, Luo HS, Smith RC, Teramoto-Matsubara OT S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S