Published online Jan 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1179

Peer-review started: May 7, 2015

First decision: August 25, 2015

Revised: September 8, 2015

Accepted: November 13, 2015

Article in press: November 13, 2015

Published online: January 21, 2016

Processing time: 262 Days and 0.9 Hours

In spite of a worldwide decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer, this malignancy still remains one of the leading causes of cancer mortality. Great efforts have been made to improve treatment outcomes in patients with metastatic gastric cancer, and the introduction of trastuzumab has greatly improved the overall survival. The trastuzumab treatment took its first step in opening the era of molecular targeted therapy, however several issues still need to be resolved to increase the efficacy of targeted therapy. Firstly, many patients with metastatic gastric cancer who receive trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapeutic agents develop resistance to the targeted therapy. Secondly, many clinical trials testing novel molecular targeted agents with demonstrated efficacy in other malignancies have failed to show benefit in patients with metastatic gastric cancer, suggesting the importance of the selection of appropriate indications according to molecular characteristics in application of targeted agents. Herein, we review the molecular targeted agents currently approved and in use, and clinical trials in patients with metastatic gastric cancer, and demonstrate the limitations and future direction in treatment of advanced gastric cancer.

Core tip: This review summarizes the development of molecular targeted therapeutic agents in advanced gastric cancer. Agents targeting angiogenesis as well as ERBB receptors and their downstream signaling pathways are introduced. Current efforts to overcome resistance to the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeted agents are also presented from the ongoing clinical trials. Future direction of target therapy should be guided according to further clarification of the molecular mechanisms of gastric cancer and by exploring appropriate indications for application of molecular targeted therapy to improve its efficacy.

- Citation: Lee SY, Oh SC. Changing strategies for target therapy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(3): 1179-1189

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i3/1179.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1179

Although the incidence of gastric cancer has been declining worldwide, it is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality[1]. Gastric cancer is frequently diagnosed at an advanced, incurable stage due to its asymptomatic feature at its early stages. Systemic chemotherapy is usually offered as treatment for patients with advanced incurable gastric cancer, but treatment outcomes are dismal, with a range of median survival of 6-11 mo[2]. Recent advances in molecular targeted therapies have led to an improved prognosis in patients with advanced, unresectable gastric cancer. A monoclonal antibody interfering with the activation of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) was the first targeted agent to demonstrate significant survival benefit in the treatment of gastric cancer. Despite the proven survival advantage of the HER2-directed monoclonal antibody in patients with HER2-overexpressing advanced gastric cancer (AGC), several problems still remain to be solved[3]. One of them is the emergence of gastric tumor cells resistant to treatment with the HER2 monoclonal antibody. In order to overcome resistance, a variety of investigational molecular targeted agents have been developed and some have shown encouraging results in clinical trials[4,5].

On the other hand, several targeted therapies have been studied in patients with AGC, but few agents have been proven to be beneficial. This is, in part, thought to be attributed to the biological heterogeneity of gastric cancer, and, therefore, careful selection of patients may be a key factor in the successful target therapies in patients with AGC.

This article reviews the molecular targeted agents in clinical use, their limitations and potential strategies to overcome them, and introduces ongoing clinical trials as well as the future direction of target therapy in unresectable AGC.

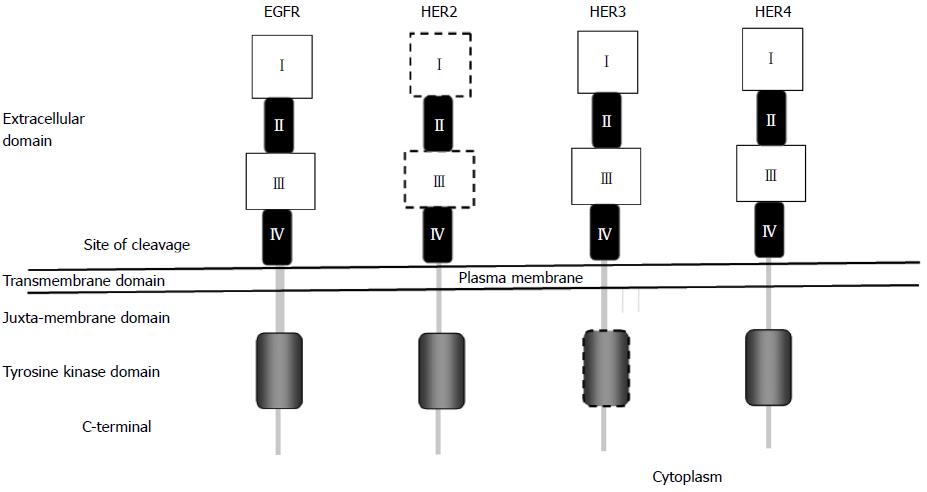

The ERBB family of receptors, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), consists of four members, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the EGFR-related receptors - HER2, HER3, and HER4. This family of receptors is transmembrane receptors consisting of an extracellular domain, a single hydrophobic transmembrane segment and an intracellular domain containing a preserved tyrosine kinase residue (Figure 1).

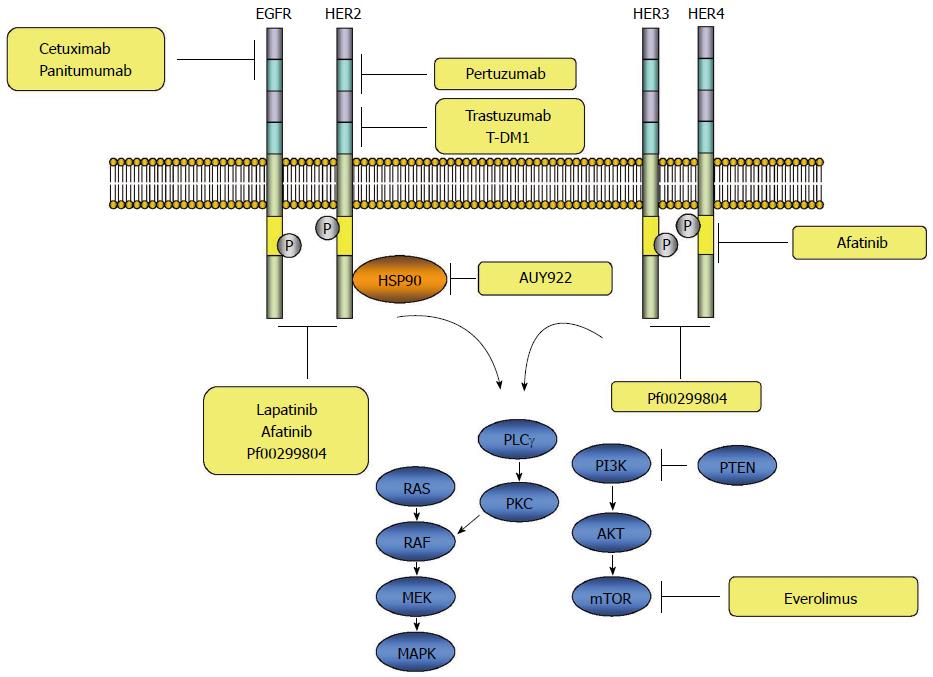

EGFR is ubiquitously expressed in epithelial, mesenchymal and neuronal cells, and plays a role in development, proliferation and differentiation[6]. The signaling through the EGFR is initiated with binding of the ligands to domain I and III of the extracellular domain, which subsequently induces formation of a heterodimer or homodimer between the receptor family members leading to autophosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase residues in the carboxy-terminus of the receptor protein. The autophosphorylated receptor subsequently activates a downstream signaling cascade through the RAS-RAF-mitogen activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs) pathway. In addition to the RAS-RAF-MAPKs, several other pathways, such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3Ks)-AKT or RAS-PLCγ-PKC are known to be activated by ERBB receptor signaling[7-10] (Figure 2).

The activation process of ERBB signaling pathway ranges from the tumorigenesis such as cell division and migration to differentiation and apoptosis, depending on cellular context[11]. ERBB receptors are associated with development and alteration of various types of cancer with several mechanisms. The best known example of the alteration is amplification of ERBB2 in a subset of breast cancers as well as in gastric, ovarian, and salivary cancers[12-14]. In non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), mutations in the tyrosine-kinase domain of EGFR have been found in a subset of patients[15-17]. With regard to tumorigenesis, ERBB receptors have been the candidates as targets for anti-cancer therapy. The ERBB receptors-targeted agents are summarized in Table 1.

| Study | n | Design | Line | Treatment | Primary end point | Results | P value |

| EXPAND[19] | 904 | Phase 3, RCT | First | Cetuximab + XP vs Placebo + XP | PFS | HR = 1.09; 95%CI: 0.92-1.29 | 0.320 |

| REAL3[22] | 553 | Phase 3, RCT | First | Anitumumab + mEOC vs EOC | OS | HR = 1.37; 95%CI: 1.07-1.76 | 0.013 |

| TOGA[3] | 594 | Phase 3, RCT | First | Trastuzumab + XP vs XP | OS | HR = 0.74; 95%CI: 0.60-0.91 | 0.005 |

| HERBIS-1[29] | 56 | Phase 2, non-RCT | First | Trastuzumab + S-1 + Cisplatin | RR | RR = 68%; 95%CI: 0.54-0.80 | |

| TyTAN[38] | 261 | Phase 3, RCT | Salvage | Lapatinib + Paclitaxel vs Paclitaxel | OS | HR = 0.84; 95%CI: 0.64-1.11 | 0.350 |

| LOGiC[39] | 545 | Phase 3, RCT | First | Lapatinib + CapeOx vs Placebo + CapeOx | OS | HR = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.73-1.12 | 0.104 |

Cetuximab: Cetuximab is a mouse/human chimeric monoclonal antibody that targets the EGFR. Treatment with cetuximab monotherapy in patients with AGC who had received prior chemotherapy showed minimal clinical activity in a phase 2 clinical trial[18]. Another study in patients with AGC treated with cetuximab in combination with irinotecan as a second-line chemotherapy, revealed that combination therapy was effective in a subset of patients [median overall survival (OS) 5.5 mo, 95%CI: 3.6-7.3][19]. The controversy was terminated by a randomized, open-label phase 3 trial (EXPAND), which showed no benefit with the addition of cetuximab to combination chemotherapy. Patients diagnosed with advanced gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer were randomized to receive capecitabine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy with or without cetuximab as a first-line chemotherapy. No significant difference in progression-free survival (PFS), the primary endpoint of the study, was shown in this study [4.4 mo vs 5.6 mo, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.09, 95%CI: 0.92-1.29, P = 0.32][20].

Panitumumab: Panitumumab is a fully human immunoglobulin (Ig) G2 monoclonal antibody directed against the EGFR. After determination of the optimal dosage of panitumumab as 9 mg/kg when used in combination with epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine in a dose-finding study[21], a randomized, open-label phase 3 trial was performed. Patients with previously untreated advanced esophagogastric adenocarcinoma were randomized to receive either epirubicin, oxaliplatin and capecitabine (EOC) or modified EOC plus panitumumab. The primary endpoint was OS, however, the addition of panitumumab did not increase OS with significantly better survival in the chemotherapy only group [11.3 mo vs 8.8 mo (panitumumab plus mEOC group), HR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.07-1.76, P = 0.013][22].

HER2 is a transmembrane RTK, which belongs to the ERBB family of receptors. Like other HER family receptors, the HER2-neu receptor consists of an ectodomain, transmembrane domain, and endodomain. The ectodomain of the receptor has four domains, including two insulin-like growth factor-like ligand binding domains (I-III) and two cysteine-rich domains (II-IV) (Figure 1). Unlike the other family members of the ERBB, no ligands for HER2 have been identified. The ligand-independent transactivation of HER2 receptors through homo- or hetero-dimerization with other ERBB family members leads to activation of a downstream signaling cascade through the RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPKs or PI3Ks-AKT-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway[23,24] (Figure 2).

Trastuzumab: Trastuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the HER2 receptor and exerts activity by binding to the domain IV of the extracellular domain[25]. Several mechanisms by which trastuzumab inhibits activation of HER2 receptors include antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)[26], inhibition of intracellular signal transduction, blocking proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular domain, reduction of tumor angiogenesis, and inhibition of recovery from DNA damage[27]. Because HER2 was reported to be amplified in 13%-23% of all gastric cancers[28], the agent targeting the HER2 receptor was introduced for the treatment of gastric cancer. Trastuzumab was the first molecule-targeted agent approved for the treatment of gastric cancer after the randomized, prospective, multicenter, phase 3 (ToGA) study. The significant survival benefit in patients overexpressing HER2 was demonstrated in ToGA study, in which patients with AGC were randomized to receive cytotoxic chemotherapy comprising fluoropyrimidine and cisplatin with or without trastuzumab (13.8 mo vs 11.1 mo, HR = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.60-0.91, P = 0.0046)[3].

Another study with truastuzumab in combination with S-1 and cisplatin reported favorable efficacy in a multicenter phase 2 trial. The HERBIS-1 study was designed for patients with HER2-positive AGC to receive S-1 and cisplatin in addition to trastuzumab, and reported a 68% response rate, 16 mo of OS, and 7.8 mo of PFS[29].

Pertuzumab: Pertuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that interferes with dimerization by binding the domain II of the HER2 ectodomain[30]. Based on a pre-clinical study, in which the anti-tumor activity of combination immunotherapy with pertuzumab and trastuzumab was proved to be superior to a monotherapy with either antibody in a HER2-positive human gastric cancer xenograft model[31], and the CLEOPATRA study that demonstrated the superior OS as well as PFS in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated with the combined pertuzumab and trastuzumab in addition to docetaxel compared with patients treated with placebo, trastuzumab and docetaxel[32,33], a phase 2a trial was designed with combination of pertuzumab, trastuzumab and chemotherapy. The dose of pertuzumab used in a phase 3 study was determined in the phase 2a trial, and a pertuzumab dose of 840 mg every three weeks for six cycles in addition to trastuzumab, capecitabine and cisplatin, showed a 55% partial response rate in patients with HER2-positive AGC without prior chemotherapy[34].

Lapatinib: Lapatinib is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that simultaneously inhibits phosphorylation of both EGFR and HER and prevents activation of the downstream signaling cascade. A pre-clinical study demonstrated effectiveness of lapatinib against p96HER-2 expressing cells which were resistant to trastuzumab because p95HER2 is an amino terminally truncated receptor with preserved kinase activity that results in interruption of trastuzumab to bind the HER2 receptor[35]. Lapatinib was proven to have clinical benefit in treatment of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in terms of OS (HR = 0.76, 95%CI: 0.60-0.96) and PFS (HR = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.50-0.74) in a meta-analysis[36].

In contrary to the proven benefit of lapatinib in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, the outcome of patients with gastric cancer is poor in clinical trials. In a phase 2 study of lapatinib used as first-line treatment, the response rate was only 9% and median OS was 4.8 mo (95%CI: 3.2-7.4)[37]. Two phase 3 trials on lapatinib also showed unsatisfactory results. In the TyTAN study, a combination of lapatinib and weekly paclitaxel was compared to weekly paclitaxel monotherapy as the second-line treatment in HER2-positive gastric cancer. No significant advantage in terms of OS (11 mo vs 8.9 mo, P = 0.1044) and PFS (5.4 mo vs 4.4 mo, P = 0.2441) was shown[38]. The efficacy of lapatinib was also studied as a first–line treatment in the LOGiC phase 3 trial. Combination chemotherapy of capecitabine and oxaliplatin with lapatinib was compared to that without lapatinib in HER2-positive gastric cancer, and no significant benefit in survival was demonstrated (HR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.73-1.12, P = 0.35) or PFS (HR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.71-1.04, P = 0.10)[39].

Despite the proven efficacy of trastuzumab in the treatment of HER2-overexpressing gastric cancer, 12% of patients treated with chemotherapy plus trastuzumab were refractory to the therapy, and disease progression eventually documented in 7 mo from the initiation of the therapy[3], suggested presence of primary resistance and development of acquired resistance against the antibody. A variety of mechanisms of acquired resistance to trastuzumab in gastric cancer has been proposed. These include: (1) dimerization or crosstalk of HER2 with other molecules such as HER3 and MET leading to subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K pathway[40]; (2) genetic alteration and subsequent aberrant activation of HER2 downstream signaling pathways[40]; (3) epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling[41]; and (4) intra-tumoral heterogeneity of gastric cancer[42,43]. To overcome these resistance-mediating mechanisms, a paradigm shift of concept for gastric cancer treatment is needed. Good candidate drugs used for cancers originating from other organs are not always good for gastric cancer due to the concept of cancer addiction difference, which means that different cancer cells use different mechanisms for carcinogenesis.

c-Met is a RTK that stimulates cell proliferation, survival and invasion/metastasis. Binding of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) to its receptor, MET, initiates activation of downstream signal transduction pathways including MAPK cascades and the PI3K-Akt axis[44]. It has been known that the Met/EGFR family receptors’ crosstalk plays a role in the development of drug resistance, such as resistance to gefitinib and erlotinib in NSCLC[45]. Furthermore, Met transcript and protein levels have also been reported to be elevated in breast cancer cells overexpresssing HER2 in response to treatment with HER2 inhibitor, suggesting that Met signaling compensates for HER2 inhibition[46]. In gastric cancer, MET gene amplification and MET protein overexpression have been reported with a frequency of 10%-20% and 50%, respectively[47,48]. Based on these findings, an open-label dose de-escalation phase 1b and double-blind randomized phase 2 trial were performed using rilotumumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG2 antibody against HGF. Patients received epirubicin, capecitabine and cisplain with or without rilotumumab. Significantly improved PFS was reported in the rilotumumab group compared to the placebo group with metastatic AGC who had not received previous systemic therapy (5.7 mo vs 4.2 mo, HR = 0.60, 80%CI: 0.45-0.79, P = 0.016)[4].

Aberrant activation of the HER2 signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, is known to be one of the mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance. As loss of function mutations in PTEN or activating mutations in PIK3CA is known to cause constitutive activation of the PI3K, use of PI3K inhibitors or mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus could overcome trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer. The efficacy of everolimus was studied in a phase 2 trial, and the results showed that disease control rate, the median OS and the median PFS were 26%, 10.1 mo (96%CI: 6.5-12.1), 2.7 mo (95%CI: 1.6-3.0), respectively, in previously treated metastatic gastric cancer patients[49]. Based on these results, a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, phase 3 trial was performed in previously treated AGC patients. Patients were assigned to receive either everolimus or placebo. The primary endpoint was OS. Although significant improvement in PFS (1.7 mo vs 1.4 mo, HR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.56-0.78, P < 0.0001) was observed, this clinical trial failed to meet the primary objective, as there was no significant difference in OS (5.4 mo vs 4.3 mo, HR = 0.9, 95%CI: 0.75-1.08, P = 0.124)[50].

Although afatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor directed to multi-ERRB family receptors, inhibits multiple tyrosine kinase receptors of ERRB family, activation of HER3 is not blocked. HER3 is regarded as an important, intimate signaling partner in HER2-mediated tumorigenesis through the PI3K/Akt pathway and is one of the molecules responsible for resistance to HER2 targeted therapies[40]. Indeed, it was reported that overexpression of HER3 was observed in trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast carcinoma cell lines after long-term trastuzumab exposure[51]. It was also reported that PI3K/Akt dependent up-regulation of HER3 mRNA and protein was observed after inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase with lapatinib, suggesting incomplete block of the PI3K pathway by HER2 inhibitors because of HER3-mediated compensation[52]. These findings indicate that the combined targeting of HER2 and HER3 may be more effective in blocking HER2 downstream signaling activation. Indeed, a preclinical study with gastric cancer cell lines demonstrated the synergistic effects of a combination of the pan-HER inhibitor (PF00299804) and trastuzumab or chemotherapeutic agents[53].

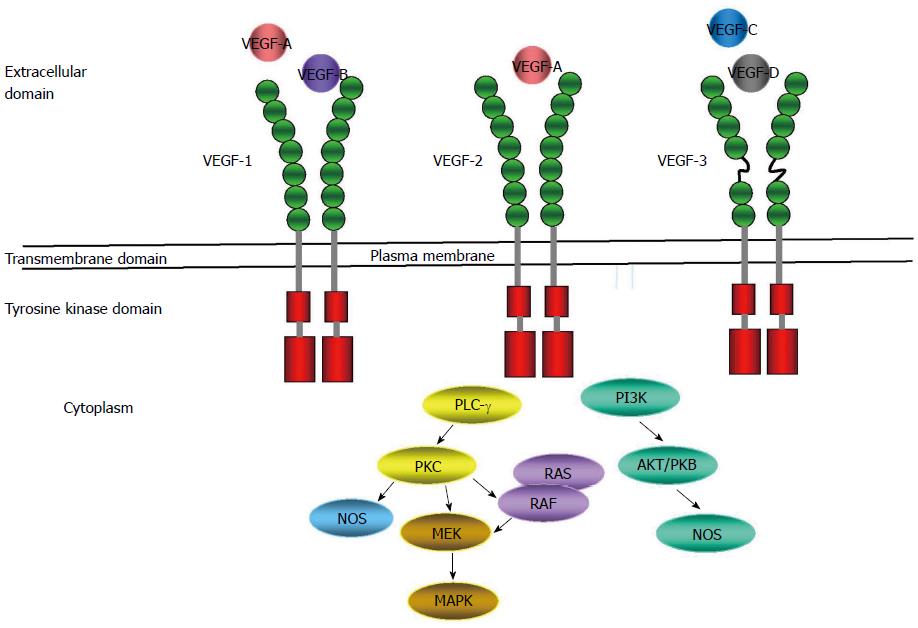

Angiogenesis is a multistep process of new vasculature formation from the pre-existing blood vessel. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated signaling is known to play an essential role in the angiogenesis and vascular permeability. In addition to these roles, it also contributes to the tumorigenesis, tumor migration and metastasis[54,55]. VEGF consists of a large family of growth factors that include VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC, VEGFD, and placental growth factor. The classical VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) that mediate signaling are RTKs VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3 expressed by vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells[54]. VEGFR2 is the predominant RTK that mediates VEGF signaling to induce angiogenesis. Despite higher affinity of VEGFR1 for binding to VEGF, the tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor is weaker than VEGFR2. The downstream signaling by activation of VEGFR2 is mediated by several pathways, including the phospholipase C-γ, protein kinase C, extracellular signal-related kinase, PI3Ks, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathways[54,56,57] (Figure 3).

In patients with gastric cancer, high expression of VEGF is known to be associated with poor prognosis[58]. Several clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of anti-angiogenic agents have been carried out in patients with gastric cancer (Table 2).

| Study | n | Design | Line | Treatment | Primary end point | Results | P value |

| AVAGAST[59] | 774 | Phase 3, RCT | First | Bevacizumab + XP vs Placebo + XP | OS | HR = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.73-1.03 | 0.1002 |

| REGARD[61] | 355 | Phase 3, RCT | Second | RAM vs Placeb | OS | HR = 0.81; 95%CI: 0.68-0.96 | 0.0470 |

| RAINBOW[62] | 665 | Phase 3, RCT | Second | RAM + paclitaxel vs Placebo + paclitaxel | OS | HR = 0.81; 95%CI: 0.68-0.96 | 0.0170 |

| Qin et al[63] | 270 | Phase 3, RCT | Third | Apatinib vs placebo | OS | HR = 0.71; 95%CI: 0.54-0.94 | 0.0160 |

Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG1 directing against VEGF-A. A large randomized phase 3 trial, Avastin in Gastric Cancer Trial, evaluated the clinical benefit of the addition of bevacizumab to combination chemotherapy. Patients with previously untreated AGC were randomized to receive bevacizumab or placebo in combination with capecitabine and cisplatin. The median overall survival (OS) between two groups was not significantly different (12.1 mo vs 10.1 mo, HR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.73-1.03, P = 0.1002) and this study failed to reach its primary objective[59].

Ramucirumab is a fully humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed to the extracellular VEGF-binding domain of VEGFR-2[60]. An international, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial was conducted in patients with AGC who had been previously treated with platinum or fluoropyrimidine-containing chemotherapy. Patients were randomly assigned to receive ramucirumab monotherapy or placebo. The significant benefit in terms of prolonged survival was demonstrated in this study (5.2 mo vs 3.8 mo, HR = 0.776, 95%CI: 0.603-0.998, P = 0.047), meeting its primary endpoint[61]. Another more recent international phase 3 trial also evaluated the clinical advantage of ramucirumab in combination with chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic AGC which progressed despite first-line chemotherapy were randomized to receive ramucirumab plus paclitaxel or placebo plus paclitaxel. Significantly longer OS was observed in the ramucirumab plus paclitaxel group (9.6 mo vs 7.4 mo, HR = 0.807, 95%CI: 0.678-0.962, P = 0.017), satisfying the primary endpoint[62]. The efficacy of ramucirumab as a first-line treatment in patients with AGC was also examined in a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter, phase 2 trial. Patients with previously untreated metastatic AGC were randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 plus ramucirumab or mFOLFOX6 plus placebo, and the primary endpoint was PFS. However, no significant improvement of PFS was observed by adding ramucirumab to mFOLFOX6 (6.4 mo vs 6.7 mo, HR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.69-1.37, P = 0.89), and the study failed to meet its primary endpoint (NCT 01246960, Clinicaltrial.gov).

Apatinib is an oral small molecular inhibitor of VEGFR-2 tyrosine kinase. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial to evaluate the survival benefit of apatinib in AGC patients with prior failure on second-line chemotherapy has been completed. Patients were randomly assigned to receive apatinib or placebo. Significantly improved OS was observed in patients treated with apatinib (6.5 mo vs 4.7 mo, HR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.54-0.94, P < 0.016), meeting the primary objective[63] (NCT01512745, ClincalTrials.gov).

Trastuzumab-emtansine (T-DM1, Genetech/Roche, South San Francisco, CA, United States) is an antibody-drug conjugate comprising trastuzumab and DM1, a microtubule inhibitor (maytansine). After binding of T-DM1 to the HER2 receptor in HER2 expressing cells, internalization occurs, and the cytotoxic DM1 moiety is released inside cells. T-DM1 also retains all the mechanisms of action of trastuzumab such as ADCC and inhibition of the downstream signaling pathway[64]. The clinical benefit of T-DM1 was demonstrated in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in phase 1 to 3 studies[65-67]. T-DM1 was also demonstrated to be more effective than trastuzumab in xenograft gastric cancer models[68]. The phase 2/3 clinical trial of T-DM1 is ongoing currently in patients with HER2-positive AGC who failed in the first- line therapy (MCT01641939; ClinicalTrials.gov).

Afatinib (GilotrifTM, Boehringer Ingelheim) is an irreversible inhibitor of the tyrosine kinases of ERBB1-2 and ERBB4 receptors. It is also reported to inhibit transphosphorylation of HER3[69]. This oral treatment agent has antitumor activity against acquired mutations resistant to first-generation inhibitors in NSCLC[70]. Clinical trials to examine the efficacy of this agent in NSCLC, breast cancer, and head and neck cancer are now underway[69]. In gastric cancer, a phase 2 trial is ongoing in patients with metastatic HER2-positive gastric cancer resistant to trastuzumab (NCT01522768; ClinicalTrials.gov).

Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is a ubiquitously expressed chaperone involved in post-translational structural folding and protein stability. The structure of HSP90 consists of an NH2-terminal region, middle region, and a COOH-terminal region, and inhibition at the NH2-terminal ATP-binding site results in degradation of the client proteins through the ubiquitin proteasome pathway[71]. NVP-AUY922 is part of the isoxazole HSP90-inhibitor family and inhibits ATPase activity. Using the gastric and breast cancer cell lines or xenograft models, AUY922 was demonstrated to have anti-proliferative activity in HER2-amplified cell lines and showed a synergistic effect with trastuzumab in trastuzumab-resistant models[72,73]. Based on these preclinical studies, a clinical trial in gastric cancer is in progress (NCT01402421, ClinicalTrials.gov).

Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG4 directed against programmed death-1 (PD-1), mainly expressed on the cell surface of regulatory T cells. PD-1 receptor is an immune-checkpoint receptor engaged by two known ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. Engagement of one of these ligands to the receptor inhibits T cell activation and eventually leads to apoptosis, which results in a blunted immune response in the tumor microenvironment[74-76]. Interruption of the engagement of the ligands to their receptors using the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody can reverse the inhibition of the immune response, and this approach has been successful in the treatment of many cancers. Evaluation of the efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with AGC is now underway in an international, multicenter, open-label phase 2 trial with treatment naïve patients or patients who received at least two prior chemotherapies (NCT02335411, Clinicaltrial.gov).

Clinical trials in molecular targeted agents for patients with AGC are reviewed in this article. The introduction of trastuzumab for a combination immune-chemotherapy in patients with AGC has taken a step forward in improving treatment outcomes. However, several limitations have been suggested in application of molecular targeted therapy.

Although abundant data from clinical trials with immune-chemotherapy in AGC has been reported, the efficacy according to the combination of target agents and chemotherapeutic agents has been different. Monotherapy with ramucirumab or a combination therapy with paclitaxel showed encouraging results in the second-line treatment. However the application of the same agent in combination with mFOLOX in the front-line treatment failed to show significant benefit[61,62]. On the other hand, lapatinib showed clinical advantage in combination with capecitabine or paclitaxel at the second-line or first-line treatment, respectively, in patients with breast cancer[77-79]. In contrast to the results in breast cancer, no benefit was shown in AGC in combination with paclitaxel or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin[38,39]. These different responses suggest the presence of different mechanisms of action by which the combination therapies exert their effects. Because signaling pathways activated by the ligand binding may be altered by different combinations of immune-chemotherapeutic agents, the possible molecular mechanisms responsible for resistance should be clarified for the right combination of therapeutic agents. Drug interaction is another possible reason. Lordick et al[20] described that one of the reasons for failure of the EXPAND trial may be related to the negative pharmacokinetic interaction between capecitabine and cetuximab, and suggested the importance of choice and schedule of fluoropyrimidine in combination with cetuximab.

The tumor component, such as molecular heterogeneity, is also an important factor to be considered. A recent study divided gastric cancer into four molecular classifications, Ebstein-Barr virus positive tumor, microsatellite unstable tumor, genomically stable tumors, and tumors with chromosomal instability[80]. Each classification has distinct molecular features, and future clinical trials should be performed in homogeneously defined subtypes of patients to raise the quality and achieve improved outcomes.

Appropriate selection of patients is also thought to be crucial before planning the clinical trials. The importance of selecting patients is highlighted in the ToGA study, in which clinical benefit was proven in selected patients overexpressing HER2[3]. In addition, expression of MET was reported to be a prognostic marker in AGC patients treated with rilotumumab, suggesting the importance of indication selection for molecular targeted therapy[4].

Despite several limitations, molecular targeted therapy is now regarded as an essential component in the treatment of cancers. In gastric cancer, numerous targeting agents have been examined in clinical trials since the introduction of trastuzumab. However, few targeted agents have been successful in establishment as a standardized therapy[3]. Resistance to trastuzumab is an emerging issue to be solved and a considerable number of preclinical studies and clinical studies are now underway to overcome this limitation. Selection of patients should always be taken into consideration when designing clinical trials given that the molecular characteristic of gastric cancer is heterogeneous. By selecting targeted agents on the basis of known molecular mechanisms, a more potent activity of the molecular target agents would be expected.

| 1. | Pullen AM, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Tolerance to self antigens shapes the T-cell repertoire. Immunol Rev. 1989;107:125-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20721] [Article Influence: 1883.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 2. | Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD004064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5823] [Cited by in RCA: 5532] [Article Influence: 345.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Iveson T, Donehower RC, Davidenko I, Tjulandin S, Deptala A, Harrison M, Nirni S, Lakshmaiah K, Thomas A, Jiang Y. Rilotumumab in combination with epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine as first-line treatment for gastric or oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: an open-label, dose de-escalation phase 1b study and a double-blind, randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1007-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Satoh T, Lee KH, Rha SY, Sasaki Y, Park SH, Komatsu Y, Yasui H, Kim TY, Yamaguchi K, Fuse N. Randomized phase II trial of nimotuzumab plus irinotecan versus irinotecan alone as second-line therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:824-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Prenzel N, Fischer OM, Streit S, Hart S, Ullrich A. The epidermal growth factor receptor family as a central element for cellular signal transduction and diversification. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:11-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne PH, Dhand R, Vanhaesebroeck B, Gout I, Fry MJ, Waterfield MD, Downward J. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase as a direct target of Ras. Nature. 1994;370:527-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1506] [Cited by in RCA: 1547] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905-2927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3190] [Cited by in RCA: 3260] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Kelley GG, Reks SE, Ondrako JM, Smrcka AV. Phospholipase C(epsilon): a novel Ras effector. EMBO J. 2001;20:743-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2345] [Cited by in RCA: 2421] [Article Influence: 105.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4920] [Cited by in RCA: 5197] [Article Influence: 207.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Holbro T, Hynes NE. ErbB receptors: directing key signaling networks throughout life. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:195-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8336] [Cited by in RCA: 8626] [Article Influence: 221.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hynes NE, Stern DF. The biology of erbB-2/neu/HER-2 and its role in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1198:165-184. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129-2139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8739] [Cited by in RCA: 8883] [Article Influence: 403.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7278] [Cited by in RCA: 7565] [Article Influence: 343.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, Singh B, Heelan R, Rusch V, Fulton L. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13306-13311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3303] [Cited by in RCA: 3468] [Article Influence: 157.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chan JA, Blaszkowsky LS, Enzinger PC, Ryan DP, Abrams TA, Zhu AX, Temel JS, Schrag D, Bhargava P, Meyerhardt JA. A multicenter phase II trial of single-agent cetuximab in advanced esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1367-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schoennemann KR, Bjerregaard JK, Hansen TP, De Stricker K, Gjerstorff MF, Jensen HA, Vestermark LW, Pfeiffer P. Biweekly cetuximab and irinotecan as second-line therapy in patients with gastro-esophageal cancer previously treated with platinum. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lordick F, Kang YK, Chung HC, Salman P, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Kurteva G, Volovat C, Moiseyenko VM, Gorbunova V. Capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:490-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in RCA: 695] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Okines AF, Ashley SE, Cunningham D, Oates J, Turner A, Webb J, Saffery C, Chua YJ, Chau I. Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine with or without panitumumab for advanced esophagogastric cancer: dose-finding study for the prospective multicenter, randomized, phase II/III REAL-3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3945-3950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Waddell T, Chau I, Cunningham D, Gonzalez D, Okines AF, Okines C, Wotherspoon A, Saffery C, Middleton G, Wadsley J. Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine with or without panitumumab for patients with previously untreated advanced oesophagogastric cancer (REAL3): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:481-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. EMBO J. 2000;19:3159-3167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1802] [Cited by in RCA: 1860] [Article Influence: 71.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Okines A, Cunningham D, Chau I. Targeting the human EGFR family in esophagogastric cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:492-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, Stanley AM, Gabelli SB, Denney DW, Leahy DJ. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature. 2003;421:756-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1185] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Barok M, Isola J, Pályi-Krekk Z, Nagy P, Juhász I, Vereb G, Kauraniemi P, Kapanen A, Tanner M, Vereb G. Trastuzumab causes antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity-mediated growth inhibition of submacroscopic JIMT-1 breast cancer xenografts despite intrinsic drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2065-2072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Spector NL, Blackwell KL. Understanding the mechanisms behind trastuzumab therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5838-5847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gravalos C, Jimeno A. HER2 in gastric cancer: a new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1523-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 737] [Cited by in RCA: 904] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Kurokawa Y, Sugimoto N, Miwa H, Tsuda M, Nishina S, Okuda H, Imamura H, Gamoh M, Sakai D, Shimokawa T. Phase II study of trastuzumab in combination with S-1 plus cisplatin in HER2-positive gastric cancer (HERBIS-1). Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1163-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Agus DB, Akita RW, Fox WD, Lewis GD, Higgins B, Pisacane PI, Lofgren JA, Tindell C, Evans DP, Maiese K. Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:127-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yamashita-Kashima Y, Iijima S, Yorozu K, Furugaki K, Kurasawa M, Ohta M, Fujimoto-Ouchi K. Pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab shows significantly enhanced antitumor activity in HER2-positive human gastric cancer xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5060-5070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Swain SM, Kim SB, Cortés J, Ro J, Semiglazov V, Campone M, Ciruelos E, Ferrero JM, Schneeweiss A, Knott A. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA study): overall survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:461-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in RCA: 754] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, Roman L, Pedrini JL, Pienkowski T, Knott A. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1741] [Cited by in RCA: 1892] [Article Influence: 135.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kang YK, Rha SY, Tassone P, Barriuso J, Yu R, Szado T, Garg A, Bang YJ. A phase IIa dose-finding and safety study of first-line pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab, capecitabine and cisplatin in patients with HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:660-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Scaltriti M, Rojo F, Ocaña A, Anido J, Guzman M, Cortes J, Di Cosimo S, Matias-Guiu X, Ramon y Cajal S, Arribas J. Expression of p95HER2, a truncated form of the HER2 receptor, and response to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:628-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 663] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Amir E, Ocaña A, Seruga B, Freedman O, Clemons M. Lapatinib and HER2 status: results of a meta-analysis of randomized phase III trials in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:410-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Iqbal S, Goldman B, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Lenz HJ, Zhang W, Danenberg KD, Shibata SI, Blanke CD. Southwest Oncology Group study S0413: a phase II trial of lapatinib (GW572016) as first-line therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2610-2615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 38. | Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, Sun GP, Doi T, Xu JM, Tsuji A, Omuro Y, Li J, Wang JW. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second-line treatment of HER2-amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN--a randomized, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2039-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hecht JR, Bang YJ, Qin S, Chung HC, Xu JM, Park JO, Jeziorski K, Shparyk Y, Hoff PM, Sobrero AF. Lapatinib in combination with capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CapeOx) in HER2-positive advanced or metastatic gastric, esophageal, or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (AC): The TRIO-013/LOGiC Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:LBA4001. |

| 40. | Shimoyama S. Unraveling trastuzumab and lapatinib inefficiency in gastric cancer: Future steps (Review). Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kim HP, Han SW, Song SH, Jeong EG, Lee MY, Hwang D, Im SA, Bang YJ, Kim TY. Testican-1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling confers acquired resistance to lapatinib in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:3334-3341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Barros-Silva JD, Leitão D, Afonso L, Vieira J, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Fragoso M, Bento MJ, Santos L, Ferreira P, Rêgo S. Association of ERBB2 gene status with histopathological parameters and disease-specific survival in gastric carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gong SJ, Jin CJ, Rha SY, Chung HC. Growth inhibitory effects of trastuzumab and chemotherapeutic drugs in gastric cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2004;214:215-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. MET signalling: principles and functions in development, organ regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:834-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 989] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Lai AZ, Abella JV, Park M. Crosstalk in Met receptor oncogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:542-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Shattuck DL, Miller JK, Carraway KL, Sweeney C. Met receptor contributes to trastuzumab resistance of Her2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1471-1477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Carneiro F, Sobrinho-Simoes M. The prognostic significance of amplification and overexpression of c-met and c-erb B-2 in human gastric carcinomas. Cancer. 2000;88:238-240. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Janjigian YY, Tang LH, Coit DG, Kelsen DP, Francone TD, Weiser MR, Jhanwar SC, Shah MA. MET expression and amplification in patients with localized gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1021-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Doi T, Muro K, Boku N, Yamada Y, Nishina T, Takiuchi H, Komatsu Y, Hamamoto Y, Ohno N, Fujita Y. Multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with previously treated metastatic gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1904-1910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Ohtsu A, Ajani JA, Bai YX, Bang YJ, Chung HC, Pan HM, Sahmoud T, Shen L, Yeh KH, Chin K. Everolimus for previously treated advanced gastric cancer: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III GRANITE-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3935-3943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Narayan M, Wilken JA, Harris LN, Baron AT, Kimbler KD, Maihle NJ. Trastuzumab-induced HER reprogramming in “resistant” breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2191-2194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Garrett JT, Olivares MG, Rinehart C, Granja-Ingram ND, Sánchez V, Chakrabarty A, Dave B, Cook RS, Pao W, McKinely E. Transcriptional and posttranslational up-regulation of HER3 (ErbB3) compensates for inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5021-5026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Nam HJ, Ching KA, Kan J, Kim HP, Han SW, Im SA, Kim TY, Christensen JG, Oh DY, Bang YJ. Evaluation of the antitumor effects and mechanisms of PF00299804, a pan-HER inhibitor, alone or in combination with chemotherapy or targeted agents in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:439-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Goel HL, Mercurio AM. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:871-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 799] [Cited by in RCA: 994] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2613] [Cited by in RCA: 2445] [Article Influence: 116.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Okines AF, Reynolds AR, Cunningham D. Targeting angiogenesis in esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2011;16:844-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2194] [Cited by in RCA: 2422] [Article Influence: 121.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Chen J, Zhou SJ, Zhang Y, Zhang GQ, Zha TZ, Feng YZ, Zhang K. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of galectin-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2073-2079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, Rha SY, Sawaki A, Park SR, Lim HY, Yamada Y, Wu J, Langer B. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968-3976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 913] [Cited by in RCA: 907] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Youssoufian H, Hicklin DJ, Rowinsky EK. Review: monoclonal antibodies to the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5544s-5548s. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, Dumitru F, Passalacqua R, Goswami C, Safran H, dos Santos LV, Aprile G, Ferry DR. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1541] [Cited by in RCA: 1625] [Article Influence: 135.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, Hironaka S, Sugimoto N, Lipatov O, Kim TY. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1613] [Cited by in RCA: 1842] [Article Influence: 153.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 63. | Geng R, Li J. Apatinib for the treatment of gastric cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:117-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Junttila TT, Li G, Parsons K, Phillips GL, Sliwkowski MX. Trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1) retains all the mechanisms of action of trastuzumab and efficiently inhibits growth of lapatinib insensitive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:347-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Krop IE, Beeram M, Modi S, Jones SF, Holden SN, Yu W, Girish S, Tibbitts J, Yi JH, Sliwkowski MX. Phase I study of trastuzumab-DM1, an HER2 antibody-drug conjugate, given every 3 weeks to patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2698-2704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Burris HA, Rugo HS, Vukelja SJ, Vogel CL, Borson RA, Limentani S, Tan-Chiu E, Krop IE, Michaelson RA, Girish S. Phase II study of the antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab-DM1 for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer after prior HER2-directed therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:398-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, Krop IE, Welslau M, Baselga J, Pegram M, Oh DY, Diéras V, Guardino E. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1783-1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2411] [Cited by in RCA: 2870] [Article Influence: 205.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Barok M, Tanner M, Köninki K, Isola J. Trastuzumab-DM1 is highly effective in preclinical models of HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2011;306:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Dungo RT, Keating GM. Afatinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2013;73:1503-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Hirsh V. Afatinib (BIBW 2992) development in non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2011;7:817-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Banerji U. Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target: some like it hot. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Eccles SA, Massey A, Raynaud FI, Sharp SY, Box G, Valenti M, Patterson L, de Haven Brandon A, Gowan S, Boxall F. NVP-AUY922: a novel heat shock protein 90 inhibitor active against xenograft tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2850-2860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Wainberg ZA, Anghel A, Rogers AM, Desai AJ, Kalous O, Conklin D, Ayala R, O’Brien NA, Quadt C, Akimov M. Inhibition of HSP90 with AUY922 induces synergy in HER2-amplified trastuzumab-resistant breast and gastric cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:509-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517-2519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9936] [Cited by in RCA: 10726] [Article Influence: 766.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 76. | Matsueda S, Graham DY. Immunotherapy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1657-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Crown J, Chan A, Kaufman B. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733-2743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2515] [Cited by in RCA: 2489] [Article Influence: 124.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Di Leo A, Gomez HL, Aziz Z, Zvirbule Z, Bines J, Arbushites MC, Guerrera SF, Koehler M, Oliva C, Stein SH. Phase III, double-blind, randomized study comparing lapatinib plus paclitaxel with placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5544-5552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Guan Z, Xu B, DeSilvio ML, Shen Z, Arpornwirat W, Tong Z, Lorvidhaya V, Jiang Z, Yang J, Makhson A. Randomized trial of lapatinib versus placebo added to paclitaxel in the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1947-1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5015] [Cited by in RCA: 5094] [Article Influence: 424.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Zhu YL S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Ma S