Published online Jun 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i24.5598

Peer-review started: March 16, 2016

First decision: March 31, 2016

Revised: April 5, 2016

Accepted: May 4, 2016

Article in press: May 4, 2016

Published online: June 28, 2016

Processing time: 100 Days and 9.4 Hours

AIM: To assess the efficacy and safety of diverting colostomy in treating severe hemorrhagic chronic radiation proctitis (CRP).

METHODS: Patients with severe hemorrhagic CRP who were admitted from 2008 to 2014 were enrolled into this study. All CRP patients were diagnosed by a combination of pelvic radiation history, clinical rectal bleeding, and endoscopic findings. Inclusion criteria were CRP patients with refractory bleeding with moderate to severe anemia with a hemoglobin level < 90 g/L. The study group included patients who were treated by diverting colostomy, while the control group included patients who received conservative treatment. The remission of bleeding was defined as complete cessation or only occasional bleeding that needed no further treatment. The primary outcome was bleeding remission at 6 mo after treatment. Quality of life before treatment and at follow-up was evaluated according to EORTC QLQ C30. Severe CRP complications were recorded during follow-up.

RESULTS: Forty-seven consecutive patients were enrolled, including 22 in the colostomy group and 27 in the conservative treatment group. When compared to conservative treatment, colostomy obtained a higher rate of bleeding remission (94% vs 12%), especially in control of transfusion-dependent bleeding (100% vs 0%), and offered a better control of refractory perianal pain (100% vs 0%), and a lower score of bleeding (P < 0.001) at 6 mo after treatment. At 1 year after treatment, colostomy achieved better remission of both moderate bleeding (100% vs 21.5%, P = 0.002) and severe bleeding (100% vs 0%, P < 0.001), obtained a lower score of bleeding (0.8 vs 2.0, P < 0.001), and achieved obvious elevated hemoglobin levels (P = 0.003), when compared to the conservative treatment group. The quality of life dramatically improved after colostomy, which included global health, function, and symptoms, but it was not improved in the control group. Pathological evaluation after colostomy found diffused chronic inflammation cells, and massive fibrosis collagen depositions under the rectal wall, which revealed potential fibrosis formation.

CONCLUSION: Diverting colostomy is a simple, effective and safe procedure for severe hemorrhagic CRP. Colostomy can improve quality of life and reduce serious complications secondary to radiotherapy.

Core tip: The study describes the efficacy and safety of diverting colostomy in treating severe hemorrhagic chronic radiation proctitis. The procedure focuses on improving the severe refractory bleeding and reducing severe complications. The advantages of diverting colostomy are as follows: it acts effectively and rapidly in controlling severe bleeding that does not respond to conservative treatment; it is a simple procedure that can be conducted in many medical centers; and it can improve quality of life dramatically and reduce serious complications that occur secondary to radiotherapy.

- Citation: Yuan ZX, Ma TH, Wang HM, Zhong QH, Yu XH, Qin QY, Wang JP, Wang L. Colostomy is a simple and effective procedure for severe chronic radiation proctitis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(24): 5598-5608

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i24/5598.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i24.5598

Chronic radiation proctitis (CRP) is a common complication after radiotherapy of pelvic malignancies, accounting for 5%-20% of cases[1]. The onset of RP can be delayed for several months to years after radiotherapy. CRP develops as a result of ischemic lesions due to obliterative endarteritis and progressive fibrosis[2,3]. Rectal bleeding is the most common symptom, which accounts for > 80% of CRP patients[4]. Acute and mild CRP is usually self-limiting and easy to manage, but moderate to severe CRP is difficult to treat; especially those cases requiring blood transfusions and that are life threatening[1,5].

Various treatment modalities have been tried. Medical agents include topical sucralfate, steroids[6], sulfasalazine[7], metronidazole[8], rebamipide[9] and short-chain fatty acid[10]. Other treatment options include topical formalin[11,12], endoscopic argon plasma coagulation (APC)[13], laser therapy[14], and hyperbaric oxygen therapy[15]. However, most of these treatments are only useful for mild to moderate bleeding, and severe and refractory bleeding is still problematic[16]. Furthermore, endoscopic treatments can bring severe side effects and multiple treatment sessions are needed for severe CRP[17]. In addition, accompanying symptoms such as intractable perianal pain, urgency and tenesmus in CRP are usually hard to manage.

Diverting colostomy has been reported previously, mainly for severe CRP complications[18,19]. Colostomy can reduce the irritation injury of fecal stream to the irradiated tissues and thus decrease rectal bleeding. However, unlike formalin or APC, colostomy is now not widely used. The issue of colostomy is not well studied to date. To the best of our knowledge, no study has compared diverting colostomy to conservative treatment. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of diverting colostomy in severe CRP. The indications, quality of life, severe CRP complications, and stoma reversals after colostomy were also investigated, when compared to conservative treatment.

Hemorrhagic CRP patients who were treated at the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (SYSU) from March 2008 to October 2014 were retrospectively enrolled in this study. Electronic files and medical records were both carefully collected to extract clinicopathological data. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of SYSU and the study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki in 1995 (revised in Tokyo, 2004). Due to the nature of the retrospective study, informed consent was waived.

Inclusion criteria were CRP patients with refractory bleeding with moderate to severe anemia with a hemoglobin level < 90 g/L. Refractory bleeding was defined as no response to conservative treatment. Patients who were treated with diverting stomas were enrolled in the study group, while those who continued to non-surgical treatment were enrolled in the control group. Patients with tumor relapses, loss to follow-up, or who underwent rectal resection with preventive colostomy were excluded.

All patients were diagnosed by combination of pelvic radiation history, clinical rectal bleeding, and endoscopic findings of injured rectal mucosa. Flexible colonoscopy was performed in all patients to rule out other causes of bleeding, such as recurrent tumors, inflammatory bowel disease and anal benign hemorrhagic diseases. The Vienna Rectoscopy Score[20] system was used to assess endoscopic severity.

Current scores to evaluate the severity of bleeding included Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events[21], Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) score[22]. However, most of them are based on subjective complaints of patients, instead of accurate laboratory tests. Because the severity of bleeding was mainly reflected by a decrease in hemoglobin level, we designed a modified Subjective Objective Management Analysis (SOMA) system reported in a previous study[23], to assess the severity of bleeding, included both subjective complaints of bleeding and objective hemoglobin level. All patients were scored by the system (Table 1). The remission of bleeding was defined as complete cessation of bleeding or only occasional bleeding that needed no further treatment. Failure in the conservative treatment group was defined as no improvement or even worse bleeding and decreased hemoglobin level 6 mo after treatment.

| Grade | Bleeding | Severity | Anemia (Hb, g/L) |

| 1 | Mild bleeding | Occasionally or occult | Mild anemia (Hb: ≥ 90 g/L) |

| 2 | Moderate bleeding | Persistent | Moderate anemia (Hb: 70-90 g/L) |

| 3 | Severe bleeding | Gross | Severe anemia, transfusion needed (Hb: < 70 g/L) |

All patients, except those with fistulas, were initially treated with medical agent enemas including almagate (one mucosa-protector like sucralfate), corticosteroids, and metronidazole. Topical formalin (details listed in our previous study)[24] or endoscopic APC were suggested when they experienced recurrent bleeding. As for refractory and transfusion-dependent CRP after these conservative measures, physicians suggested a diverting stoma. If patients refused a colostomy and demanded to continue conservative treatment, they were enrolled in the control group. Other indications of diverting colostomy were as follow: (1) fistula, perforation or stricture; and (2) deep ulcer with refractory perianal pain.

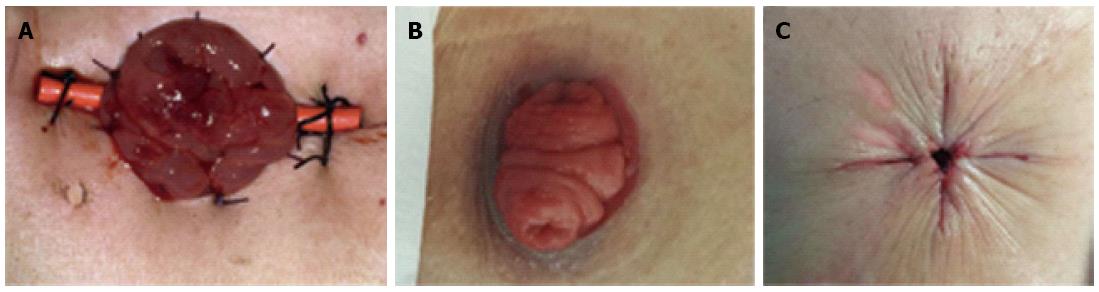

Diverting loop colostomies were conducted under general anesthesia in the operating room. The transverse colon was pulled out through a small incision, then a soft catheter of a stent was inserted to prevent stoma retraction, and a double-cavity stoma of the transverse colon was then created. The catheter was removed postoperatively. Classical images of a double-cavity colostomy and a “gunsight” of stoma closure were shown (Figure 1). This technique of stoma closure can simplify wound care, decrease surgical site infection, and give a neat cosmetic result[25,26].

Follow-up was scheduled through outpatient visits or telephone questionnaires at 6 mo and 1 year after treatment. The quality of life before treatment and at follow-up was evaluated according to EORTC QLQ C30[27]. The primary outcome was the remission rate of bleeding at 6 mo after treatment. The secondary outcomes included hemoglobin level, remission rate of bleeding at 1 year after treatment, quality of life, stoma-related complications, severe CRP complications, and stoma reversal rate.

Comparisons of characteristics were made by Student’s t test analysis for continuous variables. For categorical variables, the χ2 test was used. Fisher’s exact test was adopted when appropriate. For non-parameter variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS version 17.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). P < 0.05 (two-tails) was considered to be statistically significant.

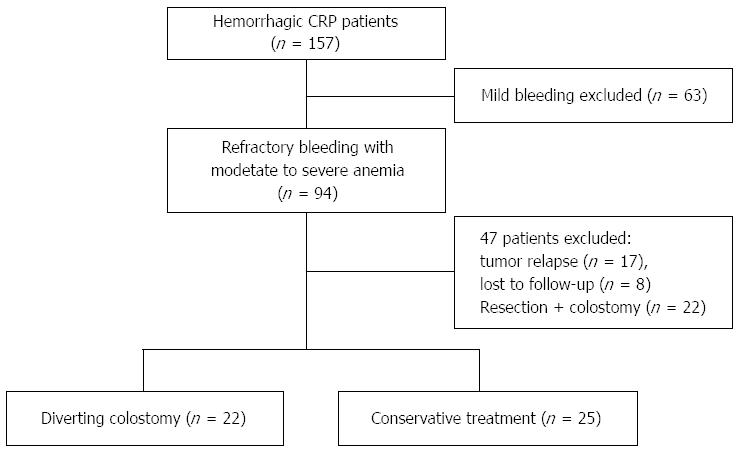

A total of 47 patients were analyzed. Twenty-two (46.8%) were treated by diverting colostomy, and 27 (53.2%) were managed by conservative treatment (Figure 2). Forty-three (91.5%) were women, and 40 (85.1%) primary malignancies were cervical cancer. Cumulative radiation dosage of one patient was about 80 Gy, which included the radiation for both sites of primary malignancy and invasive lymph nodes. The detailed radiotherapy for those patients with gynecological cancers, especially cervical cancer, was 25 rounds (2 Gy/round) of external beam radiation and five or six episodes (6 Gy/episode) of intra-cavity brachytherapy. Patients with prostate or rectal cancers received only external beam radiation. When comparing demographics prior to treatment between the two groups, there were no significant differences in age, gender, type of primary malignancy, cumulative radiation dosage, latency period, duration from treatment to end of radiotherapy, duration of bleeding, albumin level, body mass index (BMI), concomitant radiation uropathy, radiation enteritis, and associated risk factors of CRP such as previous history of abdominal surgery, diabetes mellitus and hypertension (Table 2). Thus, these above characteristics were comparable between the two groups. However, the colostomy group had a higher score of bleeding (2.7 vs 2.0, P < 0.001) and a lower hemoglobin level (60.8 g/L vs 88.2 g/L, P < 0.001), when compared to the conservative treatment group, respectively. These results indicated that the colostomy group had more serious bleeding before treatment (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Diverting colostomy (n = 22) | Conservative treatment (n = 25) | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 60.1 ± 2.2 | 60.2 ± 2.4 | 0.964 |

| Gender (female/male) | 20/2 | 23/2 | 1.0001 |

| Primary malignancy | 0.8222 | ||

| Cervical cancer | 19 (86.4) | 21 (84) | |

| Endometrial cancer | 2 (9.1) | 2 (8) | |

| Rectal cancer | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4) | |

| Prostate cancer | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| Cumulative radiation dosage (Gy), mean ± SD | 80.5 ± 17.3 | 83.6 ± 20.5 | 0.8423 |

| Latency period (mo), mean ± SD | 8.3 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 0.2523 |

| Duration from treatment to end of radiotherapy (mo), mean ± SD | 16.3 ± 1.3 | 14.8 ± 1.6 | 0.2773 |

| Duration of bleeding (month), mean ± SD | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 8.0 ± 1.8 | 0.4661 |

| Score of bleeding, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | < 0.0013 |

| Mean hemoglobin (g/L), mean ± SD | 60.8 ± 18.1 | 88.2 ± 19.3 | < 0.001 |

| Alb (g/L), ( ≤ 35/> 35) | 6/16 | 3/22 | 0.3391 |

| BMI (kg/m2), ( ≤ 17.5/> 17.5) | 3/19 | 2/23 | 0.8801 |

| Concomitant radiation uropathy | 8 (36.4) | 6 (24) | 0.355 |

| Radiation enteritis | 5 (22.7) | 2 (8) | 0.3151 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 6 (27.3) | 11 (44) | 0.234 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (9.1) | 3 (12) | 1.0001 |

| Hypertension | 6 (27.3) | 7 (28) | 0.956 |

The indications for colostomy were as follows: (1) severe bleeding in eight (36.4%) cases; (2) fistulas in 11 (50%), including nine (40.9%) rectovaginal fistulas and two (9.1%) sigmoid-vesical-vaginal fistulas; (3) deep ulcer + refractory perianal pain in two (9.1%) cases; and (4) severe bleeding + deep ulcer + anal stricture in one (4.5%) case. Among these 11 patients with fistulas, five also had concomitant severe bleeding. Among these nine recto-vaginal fistulas, one had concomitant recto-urethral fistula, and another had concomitant recto-vesical fistula and small bowel fistula.

In the conservative treatment group, seven patients received topical formalin irrigation and one received APC treatment after enrollment. All eight (32%) cases transiently obtained bleeding remission, but only two (25%) obtained long-term remission of bleeding. The other six patients experienced recurrent bleeding and developed severe anemia. Repeat topical formalin achieved only limited efficacy in these patients with severe anemia (average 2 sessions of formalin at 2-4-wk intervals). The remaining 17 patients refused formalin treatment, and thus continued retention enemas and transfusions when needed.

During a mean 22 (range: 6-77) mo of follow-up, eight (17%) patients died. The cause of death was recurrent malignancy in seven cases. The other one died of bladder perforation and sepsis that occurred secondary to radiation recto-vesical-vaginal perforation. At 6 mo after treatment, colostomy offered higher remission of bleeding (94% vs 12%, P < 0.001), higher remission of refractory perianal pain (100% vs 0%, P < 0.001), decreased scores of bleeding (1.1 vs 2.2, P < 0.001), and obvious increased hemoglobin levels (34.1 g/dL vs -12.3 g/dL, P < 0.001), compared to the conservative treatment group. At 1 year after treatment, colostomy achieved still higher remission of both moderate bleeding (100% vs 21.5%, P = 0.002) and severe bleeding (100% vs 0%, P < 0.001), acquired lower score of bleeding (0.8 vs 2.0, P < 0.001), and obviously elevated hemoglobin levels (40.3 g/dL vs -1.9 g/dL, P = 0.003), than those cases in the conservative treatment group. In addition, three recto-vaginal fistulas were found in the conservative treatment group during follow-up, but no new fistula occurred after the operation in the colostomy group. Patients who did not have bleeding remission continued conservative treatment at home (Table 3).

| Variables | Diverting Colostomy (n = 22) | Conservative treatment (n = 25) | P value |

| 6 mo after treatment | |||

| Remission of bleeding | 17/18 (94%) | 3/25 (12%) | < 0.0011 |

| Remission of refractory perianal pain | 8/8 (100%) | 0/6 (0%) | < 0.0012 |

| Score of bleeding, mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | < 0.0013 |

| Elevated Hb, mean ± SD | 34.1 ± 18.2 | -12.3 ± 9.14 | < 0.001 |

| Remission of moderate bleeding | 8/8 (100%) | 6/19 (21.5%) | 0.0022 |

| Remission of severe bleeding | 11/11 (100%) | 0/5 (0) | < 0.0012 |

| Score of bleeding, mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | < 0.0013 |

| Post-treatment recto-vaginal fistula | 0/22 | 3/25 (12%) | 0.2372 |

| Elevated Hb, mean ± SD | 40.3 ± 19.3 | -1.9 ± 32.54 | 0.003 |

Of the eight patients who received colostomy to control severe bleeding, three (37.5%) underwent stoma closure (2 cases at 9 mo and 1 at 10 mo after colostomy). All three had no bleeding and remained well after stoma reversal. Of the remaining five, all obtained bleeding remission and improved hemoglobin levels. However, among these five, one had grade IV New York Heart Association heart failure and could not risk stoma closure. Four were unsuitable for closure because of erythema and telangiectasia at 6 mo after colostomy, and two of these four had not yet reached 1 year follow-up to assess the lesion by colonoscopy.

Stoma complications were found in seven (31.8%) cases, which contained six stoma prolapses and one stoma stricture. Of these six stoma prolapses, four were managed with conservative measures by manual repositions (Grade II by Clavien-Dindo classification[28]), and two required stoma rebuilding (Grade III). One stoma stricture occurred in a stoma of the descending colon, instead of the transverse colon, and stoma stricture was managed by finger dilatation (Grade II).

The quality of life was evaluated in 41 (87.2%) patients by the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires. Because there were no similar reports in the Chinese population, the values were referred to the normal German population. Osoba et al[29] suggested that a difference of ≥ 20 points in global health was considered to be clinically relevant. In this study, when compared to pre-treatment, diverting colostomy improved quality of life, including improved global health (difference = 42, P < 0.001), improved functions like physical function (P < 0.001), role function (P < 0.001), emotional function (P < 0.001), social function (P < 0.001), and improved symptoms like fatigue (P < 0.001), pain (P = 0.001), dyspnea (P = 0.003), insomnia (P = 0.026), and diarrhea (P = 0.018). However, conservative treatment did not significantly improve quality of life at follow-up compared with before treatment (Table 4).

| QLQ-C30 scale | Ref. (Normal German population) | Diverting colostomy group (n = 18), mean (SD) | Conservative treatment group (n = 23), mean (SD) | ||||||

| Pre-treatment | Follow-up | Δ(FU)-Pre1 | Significance2 | Pre-treatment | Follow-up | Δ(FU)-Pre | Significance2 | ||

| Global health | 63.2 | 23.1 (15.1) | 64.8 (13.8) | 41.7 | < 0.001 | 47.1 (21.5) | 62.3 (25.0) | 15.2 | 0.033 |

| Physical function | 82.6 | 50.7 (17.8) | 77.8 (16.6) | 27.1 | < 0.001 | 78.0 (22.7) | 78.6 (26.1) | 0.6 | 0.856 |

| Role function | 75.0 | 34.3 (23.9) | 75.9 (27.3) | 41.6 | < 0.001 | 77.5 (24.9) | 77.5 (29.1) | 0.0 | 0.775 |

| Emotional function | 62.2 | 46.3 (27.4) | 73.6 (27.0) | 27.3 | 0.001 | 75.7 (17.6) | 80.8 (23.8) | 5.1 | 0.384 |

| Cognition function | 81.3 | 92.6 (12.7) | 93.5 (9.8) | 0.9 | 0.581 | 94.2 (15.6) | 95.7 (9.0) | 1.5 | 0.798 |

| Social function | 78.4 | 43.5 (28.9) | 65.7 (31.7) | 22.2 | 0.004 | 91.3 (20.6) | 89.1 (21.1) | -2.2 | 0.916 |

| Fatigue | 34.1 | 72.8 (12.9) | 36.4 (25.9) | -36.4 | < 0.001 | 26.6 (24.1) | 23.2 (27.2) | -3.4 | 0.695 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5.7 | 4.6 (15.5) | 1.9 (7.6) | -2.7 | 0.109 | 5.1 (15.4) | 6.5 (16.5) | 1.4 | 0.655 |

| Pain | 33.1 | 44.4 (28.3) | 14.8 (22.8) | -29.6 | 0.001 | 14.5 (21.5) | 11.6 (18.4) | -2.9 | 0.481 |

| Dyspnea | 18.8 | 42.6 (31.0) | 18.5 (22.8) | -24.1 | 0.003 | 14.5 (19.7) | 8.7 (18.0) | -5.8 | 0.210 |

| Insomnia | 38.5 | 48.1 (35.5) | 29.6 (31.2) | -18.5 | 0.026 | 21.7 (21.6) | 26.1 (31.7) | 4.4 | 0.287 |

| Appetite loss | 9.4 | 22.2 (27.2) | 13.0 (19.7) | -9.2 | 0.125 | 10.1 (25.5) | 8.7 (18.0) | -1.4 | 0.785 |

| Constipation | 9.1 | 9.3 (14.9) | 3.7 (10.5) | -5.6 | 0.066 | 8.7 (20.6) | 7.2 (22.4) | -1.5 | 0.414 |

| Diarrhea | 9.2 | 33.3 (33.3) | 22.2 (24.8) | -11.1 | 0.018 | 11.6 (23.8) | 2.9 (9.6) | -8.7 | 0.078 |

| Financial difficulties | 17.1 | 59.3 (26.2) | 50.0 (31.9) | -9.3 | 0.211 | 26.1 (31.7) | 24.6 (30.5) | -1.5 | 0.595 |

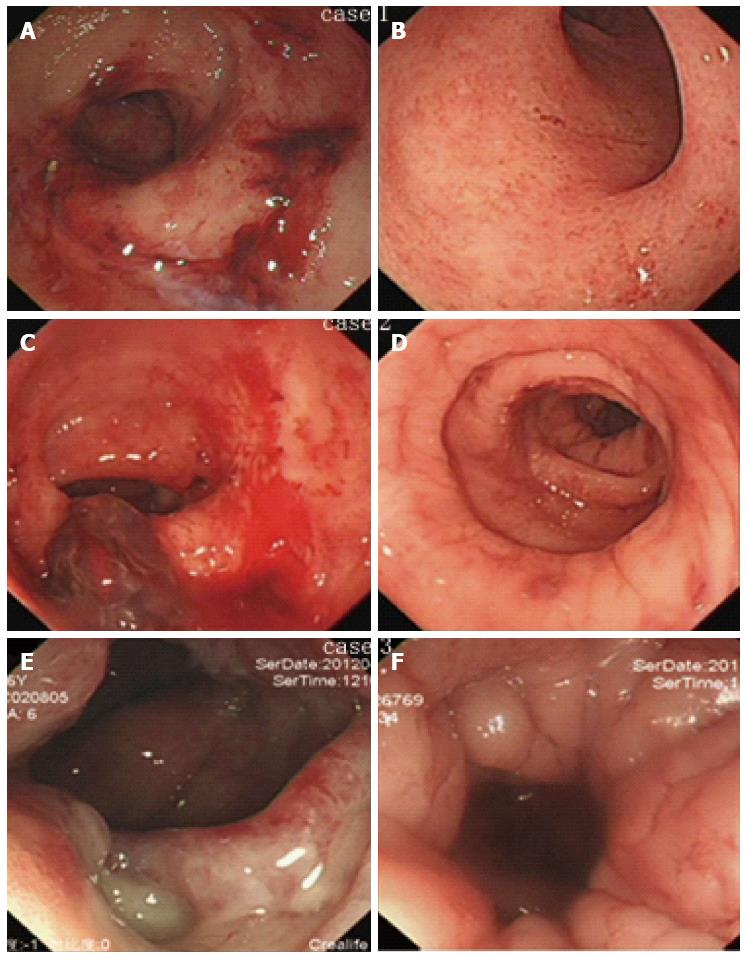

Classical endoscopic images prior to colostomy and at stoma closure from three patients with stoma closures were collected (Figure 3). After a mean 9.3 (range: 9-10) mo after colostomy, endoscopic lesions of active bleeding, multiple confluent telangiectasia, congested mucosa, or even ulcer were greatly improved and reached the criteria of stoma closure.

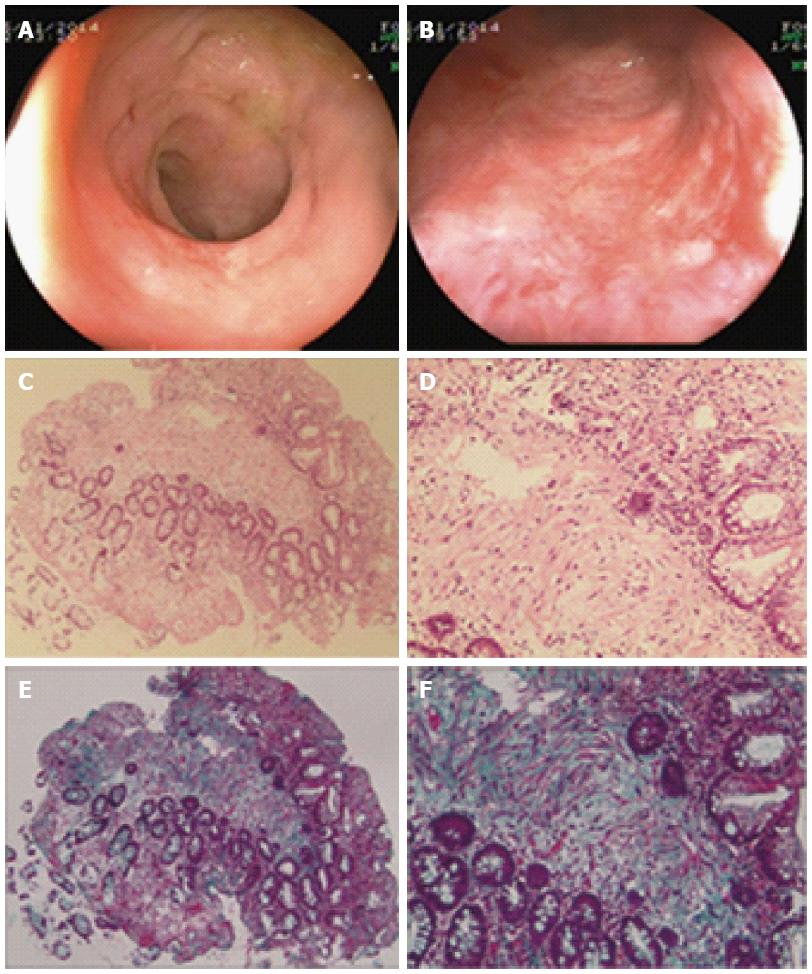

Pathological evaluation of endoscopic biopsy from rectal lesions was conducted at 31 mo after colostomy in Case 3. This patient obtained complete remission of bleeding and the biopsy sites were fully healed according to endoscopic observation at follow-up. Pathologically, diffuse chronic inflammatory cells were observed in the mucosa and sub-mucosa layers. In addition, massive fibrotic collagen depositions were found in the sub-mucosa layer, which revealed fibrosis formation (Figure 4).

Endoscopic treatments, such as topical formalin or APC, are extensively used for mild to moderate hemorrhagic CRP worldwide[14,16]. However, these treatments show only limited long-term efficacy for severe CRP[17]. It is also unclear how many patients have received these treatments for serious transfusion-dependent bleeding in previous studies[17]. Meanwhile, serious complications can be caused by these endoscopic treatments[5,17]. Our previous study also suggested that topical formalin should not be applied in CRP with ulcer because of the risk of fistula[24]. In the present study, patients in the conservative treatment group received more topical formalin or APC treatment and developed more fistulas later, than patients in the colostomy group. Therefore, we suggest topical formalin or APC should be selected cautiously for patients with severe CRP. Recently, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in treating CRP has been introduced, with improvement in hemoglobin level and decrease in clinical symptoms[30,31]. Most RFA studies are based on retrospective case series without controls and current data are scare, therefore, prospective trials of RFA should be conducted in the future to validate its efficacy and application in severe CRP.

Surgical intervention is often the last resort for severe CRP[3,19]. Rectal resection is controversial, because it is difficult to perform a safe anastomosis in the radiation-injured tissue, and high risks of anastomotic leak and death from postoperative peritonitis are reported[19]. Therefore, a simple and safe procedure to save life and relive symptoms is mandatory. Theoretically, diverting colostomy can reduce bacterial contamination and decrease irritation injury by fecal stream, and colostomy can gain time to subside any radiation reaction to protect injured tissue[32]. Thus, severe bleeding and refractory perianal pain can be controlled. Colostomy can also accelerate the course of fibrosis and relieve severe proctitis rapidly, which may prevent deep ulcers progressing to fistulas. In our recent study[33], we reported typical histopathological features of CRP: telangiectasia, abnormal hyaline-like wall vessels and sporadic radiation fibrocytes in the submucosal layer. In this study, consistently, massive fibrotic collagen depositions were observed in irradiated tissue after colostomy. Collectively, the nature of CRP is a progressive fibrosis course[7]. The efficacy and safety of colostomy have been reported in previous studies[18,19,34]. However, most previous studies did not contain controls, which could not discriminate the efficacy of interventions from the self-remission course. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has reported quality of life after colostomy. It is also not clear whether colostomy can reduce serious CRP complications.

In this study, diverting colostomy resolved most cases of severe bleeding. No recurrent bleeding and no colostomy-related death were observed. Colostomy can also decrease serious complications, including remission of long-term perianal pain, transfusion-dependent bleeding and fistula. Deep ulcer with severe bleeding is a contraindication to endoscopic treatment, because it is easy to progress to fistula, due to the poor-healing capacity and impaired blood supply of friable intestinal wall[17,19]. We have previously tried topical revision and skin flap transplantation for some CRP fistulas. However, the efficacy was limited and new fistulas can occur rapidly, due to poor healing capacity of irradiated mucosa and bacterial infection from the fecal stream, which leads to treatment failure. In this study, two patients with deep ulcer and severe bleeding were successfully controlled by colostomy, and no fistula was found at follow-up.

Transverse colostomy is preferred because it provides a greater blood supply by preserving superior rectal and left marginal vessels, and provides more options for later possible recto-sigmoid resection than sigmoid colostomy does, and transverse colostomy is easier to be closed and is more effective[32,34]. In addition, the recto-sigmoid colon is expected to receive a higher radiation dose for pelvic malignancy, while the transverse colon receives the least radiation and damage, because it is located far from pelvic tumors, and thus causes the fewest complications[19,32,35]. Loop ileostomy is not widely used because of the risk of high-volume fluid discharge. Colostomy-related complications were reported, ranging from 21.8% to 40%[19,35]. Consistent with previous studies, colostomy-related complications in this study were 31.8%, including six (85%) cases of Grade II and one (15%) case of Grade III complications. Among them, stoma prolapse was a common complication.

Colostomy for recto-vaginal fistula and rectal stricture is permanent. However, colostomy for patients unresponsive to medical treatment can be closed when severe proctitis improves sufficiently. Anseline et al[19] reported six (43%) colostomy reversals in 14 CRP patients, who were unresponsive to medical treatment. A similar result was observed in the present study. Three (38%) of eight patients with severe bleeding were closed successfully in a mean 9 mo after colostomy. Because the duration of follow-up after fecal diversion was short, many patients who obtained long-term remission of bleeding after colostomy had great potential to reverse the stoma.

In this study, we used a modified SOMA system, which coordinates subjective bleeding symptoms and objective accurate hemoglobin level. According to the system, we suggest that mild to moderate hemorrhagic CRP can be managed by medical or endoscopic treatment. However, for severe refractory bleeding colostomy should be considered to prevent development of serious complications. The scoring system will guide physicians in primary care to evaluate patient condition according to hemoglobin level, and then choose the appropriate treatment. Having a routine and easy protocol can reduce treatment-related delays and avoid unnecessary morbidity[7].

In this study, 44 (94%) CRP patients enrolled had gynecological cancers, so most fistulas were documented in women. In western countries, patients with prostate cancer are the dominant population receiving pelvic radiation, and CRP is mainly reported in prostate cancer[4,12]. However, prostate cancer receives only external beam radiation such as 3D conformal radiotherapy or intensity-modulated radiotherapy, and it does not receive intra-cavity brachytherapy, thus, fewer fistulas are observed. According to our clinical practice, intra-cavity radiation can result in more fistulas and other severe adverse radiation-related symptoms than external beam radiation can.

Although the colostomy group had more severe bleeding than the conservative treatment group, which could have resulted in selection bias, it achieved dramatically better control of bleeding, higher increased hemoglobin level, and improved quality of life compared with the conservative treatment group. These results have shown the advantages of diverting colostomy in treating severe CRP bleeding. Topical formalin or APC was not used in all the patients in the conservative treatment group, because some patients in China have not sufficient knowledge of CRP, poor compliance with physicians’ advice, and poor economic status. Thus, they choose to continue self-enemas at home, when recurrent bleeding occurs. In addition, this study was limited by its non-randomized, retrospective design and small sample size. Additional randomized prospective studies of diverting colostomy are needed to confirm our findings.

The authors thank Jie Zhao, Li-Li Chu for the contributions in the collection of stoma pictures and providing stoma cares. We also thank Yan-Qi Liu for the contribution in patient follow-up.

Chronic radiation proctitis (CRP) occurs in 5%-20% of patients receiving radiotherapy for pelvic malignant tumors. Mild to moderate CRP is usually self-limiting and easy to manage, but severe and refractory bleeding is still problematic, especially in cases requiring blood transfusions and that are life threatening. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment can cause severe side effects and only limited efficacy can be obtained for severe CRP. Thus, a simple and safe treatment with fewer complications to save life and relive symptoms is mandatory.

Diverting colostomy has been reported previously, mainly for severe CRP complications. However, unlike formalin or argon plasma coagulation, colostomy is now not widely used for severe bleeding in CRP patients. The issue of colostomy is not well studied to date. To the best of our knowledge, no study has compared diverting colostomy to conservative measures in treating severe hemorrhagic CRP.

In this series, the authors reported their experience that diverting colostomy was a simple, effective and safe procedure for severe hemorrhagic CRP. Furthermore, they found that colostomy improved quality of life and reduced serious complications secondary to radiotherapy, while conservative medical and endoscopic treatments did not show efficacy in severe CRP patients.

Diverting colostomy is a simple and safe procedure that can be performed in most medical centers. The authors also developed a modified Subjective Objective Management Analysis system, which coordinates subjective bleeding symptoms and objective accurate hemoglobin level, to guide physicians in primary care to evaluate patient condition according to hemoglobin level, and then choose the appropriate treatment. Having a routine and easy protocol can reduce treatment-related delays and avoid unnecessary morbidity.

The underlying causes of CRP are endarteritis obliterans and progressive submucosal fibrosis due to radiotherapy. Diverting colostomy can reduce bacterial contamination and decrease irritation injury by the fecal stream, and can gain time to reduce any radiation reaction to protect injured tissue. Colostomy can also accelerate the course of fibrosis and relieve severe proctitis rapidly, which may prevent deep ulcers progressing to fistulas.

This is a single center, controlled, and retrospective case series of severe CRP patients who received diverting colostomy. Colostomy can relieve most of severe bleeding rapidly and unexpected, colostomy can also reduce serious CRP complications, including remission of long-term perianal pain, transfusion-dependent bleeding and fistula.

P- Reviewer: Francois A, Pigo F S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Leiper K, Morris AI. Treatment of radiation proctitis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2007;19:724-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hasleton PS, Carr N, Schofield PF. Vascular changes in radiation bowel disease. Histopathology. 1985;9:517-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sahakitrungruang C, Thum-Umnuaysuk S, Patiwongpaisarn A, Atittharnsakul P, Rojanasakul A. A novel treatment for haemorrhagic radiation proctitis using colonic irrigation and oral antibiotic administration. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e79-e82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Placer C, Lizarazu A, Borda N, Elósegui JL, Enriquez Navascués JM. [Radiation proctitis and chronic and refractory bleeding. Experience with 4% formaldehyde]. Cir Esp. 2013;91:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Haas EM, Bailey HR, Farragher I. Application of 10 percent formalin for the treatment of radiation-induced hemorrhagic proctitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:213-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kochhar R, Patel F, Dhar A, Sharma SC, Ayyagari S, Aggarwal R, Goenka MK, Gupta BD, Mehta SK. Radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis. Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of oral sulfasalazine plus rectal steroids versus rectal sucralfate. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:103-107. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gul YA, Prasannan S, Jabar FM, Shaker AR, Moissinac K. Pharmacotherapy for chronic hemorrhagic radiation proctitis. World J Surg. 2002;26:1499-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cavcić J, Turcić J, Martinac P, Jelincić Z, Zupancić B, Panijan-Pezerović R, Unusić J. Metronidazole in the treatment of chronic radiation proctitis: clinical trial. Croat Med J. 2000;41:314-318. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kim TO, Song GA, Lee SM, Kim GH, Heo J, Kang DH, Cho M. Rebampide enema therapy as a treatment for patients with chronic radiation proctitis: initial treatment or when other methods of conservative management have failed. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:629-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Talley NA, Chen F, King D, Jones M, Talley NJ. Short-chain fatty acids in the treatment of radiation proctitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1046-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nelamangala Ramakrishnaiah VP, Javali TD, Dharanipragada K, Reddy KS, Krishnamachari S. Formalin dab, the effective way of treating haemorrhagic radiation proctitis: a randomized trial from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:876-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Patel P, Subhas G, Gupta A, Chang YJ, Mittal VK, McKendrick A. Oral vitamin A enhances the effectiveness of formalin 8% in treating chronic hemorrhagic radiation proctopathy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1605-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yeoh E, Tam W, Schoeman M, Moore J, Thomas M, Botten R, Di Matteo A. Argon plasma coagulation therapy versus topical formalin for intractable rectal bleeding and anorectal dysfunction after radiation therapy for prostate carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:954-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hanson B, MacDonald R, Shaukat A. Endoscopic and medical therapy for chronic radiation proctopathy: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1081-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Charneau J, Bouachour G, Person B, Burtin P, Ronceray J, Boyer J. Severe hemorrhagic radiation proctitis advancing to gradual cessation with hyperbaric oxygen. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:373-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Karamanolis G, Psatha P, Triantafyllou K. Endoscopic treatments for chronic radiation proctitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:308-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Andreyev J. Gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy: a new understanding to improve management of symptomatic patients. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1007-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Photopulos GJ, Jones RW, Walton LA, Fowler WC. A simplified method of complete diversionary colostomy for patients with radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis. Gynecol Oncol. 1977;5:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Anseline PF, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Radiation injury of the rectum: evaluation of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1981;194:716-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wachter S, Gerstner N, Goldner G, Pötzi R, Wambersie A, Pötter R. Endoscopic scoring of late rectal mucosal damage after conformal radiotherapy for prostatic carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2000;54:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 (CTCAE). Available from: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf. |

| 22. | Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1341-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3186] [Cited by in RCA: 3581] [Article Influence: 115.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Coia LR, Myerson RJ, Tepper JE. Late effects of radiation therapy on the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1213-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ma TH, Yuan ZX, Zhong QH, Wang HM, Qin QY, Chen XX, Wang JP, Wang L. Formalin irrigation for hemorrhagic chronic radiation proctitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3593-3598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Lim JT, Shedda SM, Hayes IP. “Gunsight” skin incision and closure technique for stoma reversal. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1569-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hsieh MC, Kuo LT, Chi CC, Huang WS, Chin CC. Pursestring Closure versus Conventional Primary Closure Following Stoma Reversal to Reduce Surgical Site Infection Rate: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:808-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11876] [Article Influence: 359.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9160] [Article Influence: 538.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139-144. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Dray X, Battaglia G, Wengrower D, Gonzalez P, Carlino A, Camus M, Adar T, Pérez-Roldán F, Marteau P, Repici A. Radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of radiation proctitis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:970-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rustagi T, Corbett FS, Mashimo H. Treatment of chronic radiation proctopathy with radiofrequency ablation (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:428-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pricolo VE, Shellito PC. Surgery for radiation injury to the large intestine. Variables influencing outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:675-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yuan ZX, Ma TH, Zhong QH, Wang HM, Yu XH, Qin QY, Chu LL, Wang L, Wang JP. Novel and Effective Almagate Enema for Hemorrhagic Chronic Radiation Proctitis and Risk Factors for Fistula Development. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:631-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ayerdi J, Moinuddeen K, Loving A, Wiseman J, Deshmukh N. Diverting loop colostomy for the treatment of refractory gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis. Mil Med. 2001;166:1091-1093. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Mäkelä J, Nevasaari K, Kairaluoma MI. Surgical treatment of intestinal radiation injury. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36:93-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |