Published online Jun 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i22.5267

Peer-review started: February 21, 2016

First decision: March 21, 2016

Revised: April 9, 2016

Accepted: May 4, 2016

Article in press: May 4, 2016

Published online: June 14, 2016

Processing time: 104 Days and 17 Hours

AIM: To demographically and clinically characterize inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from the local registry and update data previously published by our group.

METHODS: A descriptive study of a cohort based on a registry of patients aged 15 years or older who were diagnosed with IBD and attended the IBD program at Clínica Las Condes in Santiago, Chile. The registry was created in April 2012 and includes patients registered up to October 2015. The information was anonymously downloaded in a monthly report, and the information on patients with more than one visit was updated. The registry includes demographic, clinical and disease characteristics, including the Montreal Classification, medical treatment, surgeries and hospitalizations for crisis. Data regarding infection with Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) were incorporated in the registry in 2014. Data for patients who received consultations as second opinions and continued treatment at this institution were also analyzed.

RESULTS: The study included 716 patients with IBD: 508 patients (71%) were diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), 196 patients (27%) were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (CD) and 12 patients (2%) were diagnosed with unclassifiable IBD. The UC/CD ratio was 2.6/1. The median age was 36 years (range 16-88), and 58% of the patients were female, with a median age at diagnosis of 29 years (range 5-76). In the past 15 years, a sustained increase in the number of patients diagnosed with IBD was observed, where 87% of the patients were diagnosed between the years 2001 and 2015. In the cohort examined in the present study, extensive colitis (50%) and colonic involvement (44%) predominated in the patients with UC and CD, respectively. In CD patients, non-stricturing/non-penetrating behavior was more frequent (80%), and perianal disease was observed in 28% of the patients. There were significant differences in treatment between UC and CD, with a higher use of corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive and biological therapies was observed in the patients with CD (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01). Significant surgical differences were also observed: 5% of the UC patients underwent surgery, whereas 38% of the CD patients required at least one surgery (P < 0.01). The patients with CD were hospitalized more often during their disease course than the patients with UC (55% and 35% of the patients, respectively; P < 0.01). C. difficile infection was acquired by 5% of the patients in each group at some point during the disease course. Nearly half of the patients consulted at the institution for a second opinion, and 32% of these individuals continued treatment at the institution.

CONCLUSION: IBD has continued to increase in the study cohort, slowly approaching the level reported in developed countries.

Core tip: Several studies have found that the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has increased over the past several decades, even in countries where the frequency was extremely low. Industrialization, increased physician awareness, advancements in diagnostic methods and better access to medical services are factors that might explain this increase. Although few epidemiological studies have been conducted in Latin America, these analyses have described an increased incidence of IBD. In the present study, we analyzed single-center data of 716 patients with IBD. We collected data from a considerable number of patients diagnosed with IBD, enabling the demographic and clinical characterization of these individuals.

- Citation: Simian D, Fluxá D, Flores L, Lubascher J, Ibáñez P, Figueroa C, Kronberg U, Acuña R, Moreno M, Quera R. Inflammatory bowel disease: A descriptive study of 716 local Chilean patients. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(22): 5267-5275

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i22/5267.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i22.5267

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes a spectrum of typically progressive chronic diseases, including Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and unclassified colitis. Unclassified colitis occurs in patients who have clinical and endoscopic evidence of chronic IBD affecting the colon without small bowel involvement and no definitive histological or other evidence suggesting either CD or UC[1]. Although IBD mortality is low, the onset of this disease during early adulthood and its chronicity as a lifelong disease result in a significant decline in the quality of life of the patients and a heavy burden on the healthcare system due to high treatment costs[2]. Natural history studies have helped identify subsets of patients whose disease prognosis can be stratified according to clinical features. These data might improve the management of patients with IBD by defining changes in disease phenotype and risks of relapse, hospitalization and surgery[3].

Several studies have reported that the incidence of IBD has markedly increased over the latter part of the 20th century, whereas other studies have suggested a plateau or even a decline in IBD incidence in certain geographical areas[4,5]. However, an increase in these diseases has been described in countries where their frequency was very low[6-9]. IBD has been associated with the industrialization of nations[10,11], and thus, the increasing incidence of these diseases in developing countries might reflect this phenomenon. However, other factors, such as increased physician awareness, advancements in diagnostic methods and better access to medical services, such as colonoscopies, should be considered[12]. Although few epidemiological studies have been conducted in developing Latin American countries, these analyses have also described an increased incidence of IBD[13-19]. As we previously published, the incidence and prevalence of IBD in Chile are unknown; however, consistently with two other studies, our data suggest increases in the numbers of local cases of CD and UC[16,18,20]. The objective of this study was to demographically and clinically characterize IBD from a local registry and thereby update previously published data.

This was a descriptive study of a cohort based on a registry of patients aged 15 years and older, diagnosed with IBD according to clinical, endoscopic, histological and radiologic findings and attending the IBD program at Clínica Las Condes in Santiago, Chile. The registry was created in April 2012 and includes patients who attended the program until October 2015. Retrospective data were obtained from those patients diagnosed prior to the indicated date. The registry is composed of online forms available in the electronic medical record of each patient that were completed by gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons during clinic visits. On each subsequent visit, the information was prospectively updated as deemed necessary. The information was anonymously downloaded in a monthly report, and the information for patients with more than one total visit was updated. The registry includes demographic, clinical and disease characteristics, such as extension, location and behavior, changes in diagnosis from UC to CD, phenotype changes in CD, medical treatment, surgeries and hospitalizations for crisis. Data concerning Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection were incorporated into the registry in 2014. A polymerase-chain reaction assay for C. difficile detection was requested for patients presenting with moderate-to-severe activity. In CD, the Montreal Classification was used to define the phenotype as follows: B1, non-stricturing/non-penetrating; B2, stricturing; and B3, penetrating. A “p” was added to any of these classifications in case of perianal disease. The same classification was used to define the location of the disease: L1, ileum; L2, colon; L3, ileocolonic; and L4, concomitant upper gastrointestinal involvement. The extension of UC was defined according to the Montreal Classification: E1, ulcerative proctitis; E2, left-sided UC (distal UC); and E3, extensive UC (pancolitis)[1]. However, because Clínica Las Condes is a tertiary center that receives patients from locations throughout the country, the data for patients who received consultations as a second opinion and continued treatment at this institution were also analyzed. Patients with two or more visits over the next year were considered patients who were continuing treatment with the IBD program at this institution. This study was approved through the Institutional Ethics Committee.

The data were analyzed using the R Commander program. Continuous variables did not have a normal distribution and were described based on medians and ranges and compared using the Mann Whitney rank test for independent groups. Qualitative categorical variables were described with absolute frequency and percentage, and we used the χ2 test for comparative statistical analysis. When the sample was less than 20, Fisher’s exact test was used. Differences with a P value less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. A biomedical statistician conducted a statistical review of the present study.

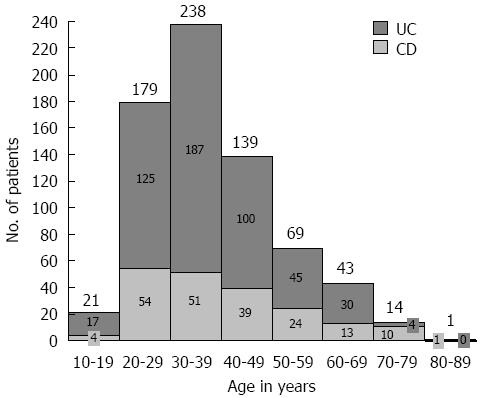

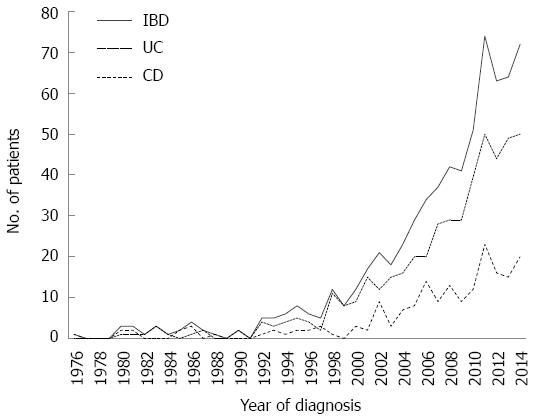

The study included 716 patients with IBD: 508 patients (71%) were diagnosed with UC, 196 patients (27%) were diagnosed with CD, and 12 patients (2%) were diagnosed with unclassifiable IBD. The UC/CD ratio was 2.6/1. The median age was 36 years (range 16-88), and 58% of the patients were female, with a median age at diagnosis of 29 years (range 5-76). Most patients with UC and CD were diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 29 years (Figure 1), without differences in gender. However, 22 patients (3%) were diagnosed when over 60 years of age. In the past 15 years, a sustained increase in the number of patients diagnosed with IBD has been observed, and significant increases were obtained from the comparison of the periods 1971-1985, 1986-2000 and 2001-2015, with 87% of patients diagnosed in the last period. The frequency of patients with IBD distributed according to the year of diagnosis is shown in Figure 2, illustrating an increase in the diagnosis of new cases of UC and CD over time. The demographic and disease characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. In both UC and CD patients, articular symptoms were the most frequent extraintestinal manifestations. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) was diagnosed in eight patients (2%) with UC and two patients (1%) with CD.

| UC (n = 508) | CD (n = 196) | |

| Smoking habit | ||

| Active | 47 (9) | 31 (16) |

| Discontinued | 75 (15) | 34 (17) |

| Family history of IBD | 59 (12) | 19 (10) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | ||

| Articular | 156 (31) | 87 (44) |

| Dermatological | 11 (2) | 10 (5) |

| Ocular | 8 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Other | 31 (6) | 15 (8) |

Regarding the extent of UC, 50% of patients had extensive colitis. In CD, 44% of patients had colonic involvement, and only 3% of patients presented with concomitant upper disease. One patient in the registry presented with isolated perianal disease, and CD was confirmed through biopsies of the fistula, which demonstrated granulomas. Non-stricturing/non-penetrating behavior was predominant in CD (80%). Stricturing and penetrating behavior was observed in 10% and 9% of patients, respectively. Perianal disease was observed in 28% of the patients with CD (Table 2). During the course of IBD, the diagnosis of 19 patients changed: one patient with unclassifiable IBD was newly diagnosed with CD, and 18 UC patients were newly diagnosed with CD. In six patients, CD was posteriorly diagnosed because these individuals developed perianal fistulas. In addition, 16 patients with CD showed modified behavior, nine of these patients showed changes from non-stricturing/non-penetrating to stricturing disease and seven of them showed changes from non-stricturing/non-penetrating to penetrating disease. In addition, two patients who are included in the 16 patients mentioned above developed perianal disease. Changes in disease extension were observed in 36 UC patients. Specifically, 12 of these 36 patients presented disease extension from proctitis to left colitis, and the remaining 24 patients exhibited disease extension from proctitis or left colitis to extensive colitis.

| UC (n = 508) | CD (n = 196) | |

| UC Extent | ||

| E1: Ulcerative proctitis | 142 (28) | |

| E2: Left sided UC | 112 (22) | |

| E3: Extensive UC (pancolitis) | 254 (50) | |

| CD Location | ||

| L1: Ileal | 53 (27) | |

| L2: Colonic | 87 (44) | |

| L3: Ileocolonic | 55 (28) | |

| L4: Upper gastrointestinal | 5 (3) | |

| CD Behavior | ||

| B1: Non-stricturing/non-penetrating | 157 (80) | |

| B2: Stricturing | 20 (10) | |

| B3: Penetrating | 18 (9) | |

| p: Perianal disease | 55 (28) |

Significant differences in treatment were found between UC patients and CD patients (Table 3). Mesalamine was used to treat 98% of UC patients and 68% of CD patients. Patients with CD received corticosteroids, mesalamine and immunosuppressive agents at equal frequency. A comparison of both groups revealed that the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive and biological therapies was significantly higher in patients with CD. A total of 102 patients (14%) were treated with biological therapy; specifically, 83 patients received infliximab, 13 patients received adalimumab, one patient received certolizumab pegol, one patient received golimumab and four patients received natalizumab. Biological therapy was initiated one year (median) after diagnosis for patients diagnosed since 2010 (39 patients) because biological therapy has become more accessible since then.

| UC (n = 508) | CD (n = 196) | P value | |

| Corticosteroids | 297 (58) | 133 (68) | < 0.05 |

| Mesalazine (oral, local or both) | 497 (98) | 133 (68) | < 0.01 |

| Immunosupressive agents | 166 (33) | 132 (67) | < 0.01 |

| Ciclosporine | 7 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Biologic therapy | 34 (7) | 67 (34) | < 0.01 |

| Surgery | 27 (5) | 75 (38) | < 0.01 |

| Intestinal resection | 27 (5) | 50 (25) | < 0.01 |

| Hospitalizations | 176 (35) | 108 (55) | < 0.01 |

| 1 | 113 (64) | 50 (46.3) | < 0.01 |

| 2-3 | 45 (26) | 35 (32.3) | |

| ≥ 4 | 18 (10) | 23 (21.3) | < 0.011 |

A comparison revealed that more CD than UC patients required surgery. Specifically, only 27 UC patients (5%) underwent surgery, whereas 75 CD patients (38%) underwent surgery (P < 0.01) (Table 3). Fifty of the patients diagnosed with CD (25%) underwent intestinal resection, and six of these patients (3%) required surgery for posteriorly based perianal disease. In addition, 24 CD patients (12%) underwent surgery due only to perianal disease, and one patient underwent a loop ileostomy.

CD patients were hospitalized more often during the disease course than UC patients (55% and 35% of patients, respectively; P < 0.01). In addition, 21.3% of the CD patients had more than four hospitalizations compared with 10% of the UC patients (P < 0.01). The median number of hospitalizations for both was 2, with ranges from 1 to 24 for UC and 1 to 40 for CD (Table 3).

As previously described, data concerning C. difficile infection were incorporated into the registry in 2014, and a total of 490 patients (344 UC patients and 141 CD patients) were analyzed. No differences in the prevalence of infection was found between the groups, and 5% of the patients in each group acquired C. difficile infection at some point during the disease course.

The data obtained from the registry showed that 328 patients (46%) received consultations at the institution for a second opinion. Most of these patients (72%) were diagnosed with UC, and 107 of the 328 patients (32%) continued treatment at this center. However, 130 patients were not analyzed because these individuals received consultations late in 2015 and had therefore not completed more than one year of treatment since the first consultation at this institution. In addition, many patients live in other cities and receive consultations only for complex situations.

The number of patients in the registry more than doubled compared with the number detailed in our previous publication[20]. This increase not only allowed us to better characterize these patients but also facilitated a comparison with studies conducted worldwide. This population increase reflects not only the recognition of this institute as a referral center but also the increased rate of IBD diagnoses in recent years.

The cohort UC/CD ratio in 2014 was 2.9/1, and the current ratio has increased 2.6/1, showing a slow approaching to the ratio reported in developed countries (1/1)[6,13,21,22]. However, genetic, environmental and geographic factors may influence this difference. A gender-based analysis showed that the percentages of UC and CD were slightly higher in women, which is consistent with the results obtained by other series[13,14,17]. The median age at diagnosis was 29 years, and 64% of patients were diagnosed between 20 and 39 years of age. No second peak was observed at an older age, which is consistent with the results from recent studies[6,7,23-25].

An active smoking habit was almost twice as frequent in patients with CD (16%) compared with patients with UC (9%), regardless of whether the patients with CD received counseling and were told of the particular deleterious effect of smoking. This finding demonstrates that smoking education is important and that smoking cessation should be emphasized on every visit. Nonetheless, the frequencies of patients with active smoking habits observed in the present study were low compared with the frequency of active smokers in the general population. The last National Health Survey has demonstrated that 40.6% of the adult population smokes regularly, indicating that cigarette smoking is an important health problem in Chile and that other factors, such as environmental factors, may be influencing the increase in the diagnosis of CD[26].

A family history was obtained for 12% and 10% of the patients diagnosed with UC and CD, respectively, similarly to the results reported by Moller et al[27], who published a much larger study. The analysis of the clinical characteristics revealed that the most frequent extra-intestinal manifestation was articular symptoms, with frequencies of 31% and 44% in UC and CD patients, respectively. In previous studies, musculoskeletal manifestations were described as the most common extra-intestinal manifestation, and UC patients are more affected than CD patients. However, the percentage of affected patients was lower than that observed in the present study (20%-30%)[28]. It has been suggested that the risk of developing peripheral arthritis increases with an increase in the extent of IBD activity[29,30], and 70% of patients diagnosed with CD who showed musculoskeletal manifestations had either colonic or ileocolonic involvement, whereas 55% of the patients diagnosed with UC who showed musculoskeletal manifestations had pancolitis. This observation reflects the recognition of this institution as a tertiary referral center that receives complex patients. In addition, the etiology of peripheral arthritis in IBD might reflect a combination of genetic predisposition and exposition to the luminal bacterial bowel contents[30].

The analysis of the extent of UC showed that half of the patients had extensive colitis, different from the frequency described in previous studies, which reported that distal location predominates[9] and that extensive colitis varies between 20 and 40%[7,9,19,22,24,31]. Even a previous study published in Chile, which involved two different institutions, reported 38% and 15% extensive colitis; notably, the frequency of 15% was previously reported at our institution 10 years ago[18], before this institution was recognized as a referral center and before its association with an IBD program. The higher percentage of extensive colitis observed in the population examined in the present study might reflect the fact that it was conducted at a tertiary referral center and included refractory cases that were difficult to treat.

Colonic involvement was more frequent in the CD patients examined in the present cohort, with a frequency of 44%. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Brazil, which found that colonic involvement predominates, although at a lower frequency (36%)[19]. Non-structuring/non-penetrating behavior was more frequently observed in the cohort examined in the present study, with a frequency of 80%. This value is consistent with the frequency described in previous studies, which showed that inflammatory phenotypes predominate during the first years of the disease[24]. During the disease course, approximately 10% of patients with non-stricturing/non-penetrating behavior exhibited a modification of this characteristic to a more aggressive behavior. However, other studies have reported that 31% to 60% of patients exhibit a disease progression to a more severe behavior[32-34]. Indeed, after 40 years, most patients experience complications and are classified as having a penetrating, or less often, a stricturing disease[16]. These differences might reflect the short follow-up period used in the present study. Additionally, it has been reported that colonic disease remains uncomplicated or inflammatory for many years[24], so predominant colonic involvement found in our study might play a role in this progression. Another factor potentially explaining this difference is that the patients at this institution were aggressively treated upon diagnosis with an “accelerated step-up approach”, involving the initiation of biological therapy a median of one year after diagnosis for patients diagnosed since 2010; thus, patients might have a lower probability to exhibit a change in behavior[35,36].

During the IBD course, 12 patients (2.3%) with an initial diagnosis of UC developed perianal fistulas or showed ileal involvement, changing their diagnosis to CD, as confirmed through histological and image analyses. Previous studies have described a 5%-10% change in diagnosis after 25 years of the disease course[37]. This finding might reflect the short follow-up period in the present study.

The analysis of IBD treatment revealed that mesalamine was the most used drug in UC treatment (98%), whereas corticosteroids, mesalamine and immunosuppressive agents were used at equal frequencies (67%-68%) in CD treatment. In the present study, despite the frequent use of mesalamine for patients with CD, the use of this agent in CD is controversial. Indeed, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization Consensus recently stated that oral aminosalicylates are not recommended for the treatment of mild to moderate CD[38]. However, both the American and British National Gastroenterology Associations recommend the use of high-dose 5-aminosalicylic acid as the first-line treatment of mild ileal, ileocolonic or colonic CD[38]. Because we had a high percentage of patients with colonic involvement, treatment with mesalamine could have had some implications because the action of mesalamine is predominantly topical at the site of inflammation, particularly within the colon[38]. However, many of these patients received mesalamine, regardless of the severity of the disease, prior to evaluation at this institution, possibly resulting from misinformation regarding the role of mesalamine in CD. On the other hand, according to the latest clinical guidelines, the use of immunosuppressive and biological therapies is significantly higher in CD patients compared with UC patients, as observed in the present study. In the series examined in the present study, the use of infliximab in UC treatment (7%) was similar to that reported in other countries[31,39,40]; however, the use of this drug in CD treatment (34%) was considerably higher than that detailed in Saudi Arabia, Israel and some European countries, which report frequencies between 2% and 10%[31,40]. Similarly, the use of immunomodulators was considerably higher in both groups compared with that observed in some European countries[31]. This discrepancy reflects the type of center where the present study was conducted, i.e., a tertiary center that treats patients with more complex diseases. Unfortunately, the use of adalimumab and certolizumab pegol was extremely low in the cohort examined in the present study, reflecting the low coverage of these therapies by insurance companies. In addition, vedolizumab is still not available for use in Chile.

The investigation of the use of surgery for IBD treatment revealed that 38% of the CD patients required surgery for either intestinal resection or perianal disease. The frequency of intestinal resection was significantly higher in CD patients (25%) compared with that of colectomy in UC patients (5%), a result consistent with the findings reported by Niewiadomski et al[41], who showed that the risk of intestinal resection in CD was 13% after one year and 26% after five years. However, the colectomy rates in UC obtained in this study were 2% and 13% after one and five years, respectively. Notably, the early use of immunomodulators and biological therapies during the disease course could reduce the risk of surgery[24,42], particularly for those patients who achieve mucosal healing[43].

Relatively few data are available regarding the hospitalization rates in population-based cohorts[44,45]. The CD patients in the cohort examined in the present study had significantly more hospitalizations than the UC patients; however, higher percentages of patients belonging to both groups in this cohort were affected compared with the frequencies obtained in previous studies[41,46]. Nevertheless, it has previously been reported that more than one-third of UC patients require hospitalization within one year after diagnosis in the biological era[44]. Among the UC patients examined in the present study, 35% required hospitalization at some point during the disease course. The disease extent at diagnosis and the need for steroids and anti-TNF therapy were associated with the risk of UC-related hospitalization[44]. For CD, a 52.7% cumulative risk of hospitalization within ten years of diagnosis has previously been described[45]. Among the CD patients in the present study, 55% required hospitalization at some point during the disease course.

The analysis of our data concerning IBD and C. difficile infection demonstrated that this bacterium was equally prevalent in patients with UC and patients with CD (5%). Notably, it is difficult to clinically distinguish between C. difficile infections and IBD flare-ups because both pathologies have similar presentations, i.e., diarrhea and abdominal pain. Indeed, C. difficile might mimic or even trigger an IBD flare-up, and screening is therefore recommended at every flare-up experienced by these patients[47]. Because IBD patients with concomitant C. difficile infections have been associated with longer hospital stays, colectomy and even higher mortality, the diagnosis of this bacterial infection is important[48]. The data obtained in the present study differ from those detailed in previous publications, which reported that UC patients exhibit increased susceptibility to C. difficile compared with CD patients[48-50]; however, previous studies have reported that one of the major risk factors for C. difficile infection in patients with IBD is colonic IBD[51], and 44% of the patients with CD in the present study showed colonic involvement. Importantly, only patients with moderate-to-severe activity were examined for C. difficile infections, and hence, these data might be underestimated because patients with mild activity were not examined.

In conclusion, IBD has continued to increase in the present cohort, slowly approaching the levels reported in developed countries. The association of this institution with a multidisciplinary IBD program has improved the characterization of these patients and had therefore improved management options.

The present study was conducted in a private single tertiary center, which may have resulted in bias because many of the patients received consultations for second opinions. Some of these individuals were inadequately treated, whereas others are refractory to therapy; therefore, these patients could represent more complex cases. In addition, more drugs are available for treatment in our center compared with those available at the public hospitals in Chile. In addition, the presented findings were obtained retrospectively, implying a selection bias. Nevertheless, we collected data from a considerable number of patients diagnosed with IBD, enabling a demographic and clinical characterization of these individuals. Unfortunately, in the present study, we were unable to determine incidence or prevalence rates because we did not receive patients from a determinate geographic area.

We wanted to thank Magdalena Castro biomedical statistician and member of the Academic Research Unit from Clínica Las Condes who conducted the statistical review of this study.

Several studies have reported that the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has increased over the past several decades, even in countries where the frequency of this disease is low. Industrialization, increased physician awareness, advancements in diagnostic methods and greater access to medical services are factors that might explain this rise.

Although few epidemiological studies have been conducted in Latin America, these studies have also described an increased incidence of IBD. The incidence and prevalence of IBD in Chile are unknown; however, increases in the numbers of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) cases have been suggested. The research goal of this study was to actualize previously published data to better demographically and clinically characterize IBD in patients from Chile.

The present study represents the largest series of IBD patients reported in Chile and even in South America. These data demonstrated an increase in the number of IBD cases.

The data used in this study not only enable the characterization of patients locally but also facilitate the comparison of these individuals with those included in other studies conducted worldwide. The characterization of these patients enabled treatment optimization, thereby improving patient quality of life.

IBD includes a spectrum of typically progressive chronic diseases, including CD, UC and unclassified colitis. Although IBD mortality is low, the onset of this disease during early adulthood and its chronicity as a lifelong disease lead to a significant decline in the quality of life of IBD patients and an increase in the burden on the healthcare system due to high treatment costs.

The paper is good written, an intersting paper regarding IBD in developing country with different results about disease distrubution, severity and treatment.

| 1. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in RCA: 2445] [Article Influence: 122.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Malekzadeh MM, Vahedi H, Gohari K, Mehdipour P, Sepanlou SG, Ebrahimi Daryani N, Zali MR, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Safaripour A, Aghazadeh R. Emerging Epidemic of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Middle Income Country: A Nation-wide Study from Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:2-15. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ng SC, Zeng Z, Niewiadomski O, Tang W, Bell S, Kamm MA, Hu P, de Silva HJ, Niriella MA, Udara WS. Early Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Population-Based Inception Cohort Study From 8 Countries in Asia and Australia. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:86-95.e3; quiz e13-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Logan RF. Inflammatory bowel disease incidence: up, down or unchanged? Gut. 1998;42:309-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Loftus EV. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2085] [Cited by in RCA: 2174] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, Wong TC, Leung VK, Tsang SW, Yu HH. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158-165.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Petritsch W, Fuchs S, Berghold A, Bachmaier G, Högenauer C, Hauer AC, Weiglhofer U, Wenzl HH. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in the province of Styria, Austria, from 1997 to 2007: a population-based study. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:58-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Burisch J, Munkholm P. Inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Ouakaa-Kchaou A, Gargouri D, Bibani N, Elloumi H, Kochlef A, Kharrat J. Epidemiological evolution of epidemiology of the inflammatory bowel diseases in a hospital of Tunis. Tunis Med. 2013;91:70-73. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Zheng JJ, Zhu XS, Huangfu Z, Gao ZX, Guo ZR, Wang Z. Crohn’s disease in mainland China: a systematic analysis of 50 years of research. Chin J Dig Dis. 2005;6:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Desai HG, Gupte PA. Increasing incidence of Crohn’s disease in India: is it related to improved sanitation? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:23-24. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3789] [Cited by in RCA: 3599] [Article Influence: 257.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 13. | Victoria CR, Sassak LY, Nunes HR. Incidence and prevalence rates of inflammatory bowel diseases, in midwestern of São Paulo State, Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Yepes I, Carmona R, Díaz F, Marín-Jiménez I. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease in Cartagena, Colombia. Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2010;25:106-109. |

| 15. | Appleyard CB, Hernández G, Rios-Bedoya CF. Basic epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Puerto Rico. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:106-111. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Quintana C, Galleguillos L, Benavides E, Quintana JC, Zúñiga A, Duarte I, Klaassen J, Kolbach M, Soto RM, Iacobelli S. Clinical diagnostic clues in Crohn’s disease: a 41-year experience. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2012;2012:285475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Linares de la Cal JA, Cantón C, Hermida C, Pérez-Miranda M, Maté-Jiménez J. Estimated incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Argentina and Panama (1987-1993). Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1999;91:277-286. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Figueroa C C, Quera P R, Valenzuela E J, Jensen B C. [Inflammatory bowel disease: experience of two Chilean centers]. Rev Med Chil. 2005;133:1295-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Parente JM, Coy CS, Campelo V, Parente MP, Costa LA, da Silva RM, Stephan C, Zeitune JM. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1197-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Simian D, Estay C, Lubascher J, Acuña R, Kronberg U, Figueroa C, Brahm J, Silva G, López-Köstner F, Wainstein C. [Inflammatory bowel disease. Experience in 316 patients]. Rev Med Chil. 2014;142:1006-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Arin Letamendia A, Borda Celaya F, Burusco Paternain MJ, Prieto Martínez C, Martínez Echeverría A, Elizalde Apestegui I, Laiglesia Izquierdo M, Macias Mendizábal E, Tamburri Moso P, Sánchez Valverde F. [High incidence rates of inflammatory bowel disease in Navarra (Spain). Results of a prospective, population-based study]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:111-116. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Zeng Z, Zhu Z, Yang Y, Ruan W, Peng X, Su Y, Peng L, Chen J, Yin Q, Zhao C. Incidence and clinical characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease in a developed region of Guangdong Province, China: a prospective population-based study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1148-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 23. | Bernstein CN, Shanahan F. Disorders of a modern lifestyle: reconciling the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2008;57:1185-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 24. | Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1390] [Cited by in RCA: 1601] [Article Influence: 106.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 25. | Gower-Rousseau C, Vasseur F, Fumery M, Savoye G, Salleron J, Dauchet L, Turck D, Cortot A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: new insights from a French population-based registry (EPIMAD). Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Repetto P, Bernales M. [Perception of smoking rates and its relationship with cigarette use among Chilean adolescents]. Rev Med Chil. 2012;140:740-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Moller FT, Andersen V, Wohlfahrt J, Jess T. Familial risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study 1977-2011. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:564-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Blanchard JF. The clustering of other chronic inflammatory diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:827-836. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Brown SR, Coviello LC. Extraintestinal Manifestations Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:1245-159, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rothfuss KS, Stange EF, Herrlinger KR. Extraintestinal manifestations and complications in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4819-4831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Shonová O, Vind I, Avnstrøm S, Thorsgaard N. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lakatos PL, Czegledi Z, Szamosi T, Banai J, David G, Zsigmond F, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Gemela O, Papp J. Perianal disease, small bowel disease, smoking, prior steroid or early azathioprine/biological therapy are predictors of disease behavior change in patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3504-3510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Lovasz BD, Lakatos L, Horvath A, Szita I, Pandur T, Mandel M, Vegh Z, Golovics PA, Mester G, Balogh M. Evolution of disease phenotype in adult and pediatric onset Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2217-2226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, Gendre JP. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244-250. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Ordás I, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Early use of immunosuppressives or TNF antagonists for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: time for a change. Gut. 2011;60:1754-1763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 36. | Ghazi LJ, Patil SA, Rustgi A, Flasar MH, Razeghi S, Cross RK. Step up versus early biologic therapy for Crohn’s disease in clinical practice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1397-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Iacucci M, de Silva S, Ghosh S. Mesalazine in inflammatory bowel disease: a trendy topic once again? Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:127-133. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Fadda MA, Peedikayil MC, Kagevi I, Kahtani KA, Ben AA, Al HI, Sohaibani FA, Quaiz MA, Abdulla M, Khan MQ. Inflammatory bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: a hospital-based clinical study of 312 patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 40. | Zvidi I, Fraser GM, Niv Y, Birkenfeld S. The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in an Israeli Arab population. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e159-e163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Hair C, Wilson J, Ding NS, Heerasing N, Ting A, McNeill J, Knight R, Santamaria J. Prospective population-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease in the biologics era: Disease course and predictors of severity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1346-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, Fedorak DK, Kroeker KI, Dieleman LA, Halloran BP, Fedorak RN. Anti-TNF Therapy Within 2 Years of Crohn’s Disease Diagnosis Improves Patient Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:870-879. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Mucosal Healing Is Associated With Improved Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Golovics PA, Lakatos L, Mandel MD, Lovasz BD, Vegh Z, Kurti Z, Szita I, Kiss LS, Balogh M, Pandur T. Does Hospitalization Predict the Disease Course in Ulcerative Colitis? Prevalence and Predictors of Hospitalization and Re-Hospitalization in Ulcerative Colitis in a Population-based Inception Cohort (2000-2012). J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:287-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Golovics PA, Lakatos L, Mandel MD, Lovasz BD, Vegh Z, Kurti Z, Szita I, Kiss LS, Pandur T, Lakatos PL. Prevalence and predictors of hospitalization in Crohn’s disease in a prospective population-based inception cohort from 2000-2012. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7272-7280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Burisch J, Pedersen N, Cukovic-Cavka S, Turk N, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Shonová O, Vind I, Avnstrøm S, Thorsgaard N. Initial disease course and treatment in an inflammatory bowel disease inception cohort in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:36-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Cojocariu C, Stanciu C, Stoica O, Singeap AM, Sfarti C, Girleanu I, Trifan A. Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:603-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG. Excess hospitalisation burden associated with Clostridium difficile in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2008;57:205-210. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Nguyen GC, Kaplan GG, Harris ML, Brant SR. A national survey of the prevalence and impact of Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1443-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Rodemann JF, Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Seo DH, Stone CD. Incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 51. | Nitzan O, Elias M, Chazan B, Raz R, Saliba W. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease: role in pathogenesis and implications in treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7577-7585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Abu Freha N, Korelitz BI, Tandon RK S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN