Published online May 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i19.4776

Peer-review started: December 16, 2015

First decision: December 30, 2015

Revised: February 2, 2016

Accepted: March 1, 2016

Article in press: March 1, 2016

Published online: May 21, 2016

Processing time: 154 Days and 15.2 Hours

Human sparganosis is a rare parasitic disease caused by infection with the tapeworm Sparganum, the migrating plerocercoid (second stage) larva of Spirometra species. Sparganosis usually involves subcutaneous tissues and/or muscles of various parts of the body, but involvement of other sites such as the brain, eye, peritoneopleural cavity, urinary track, scrotum, and abdominal viscera has also been documented. Infections caused by sparganum have a worldwide distribution but are most common in Southeast Asia such as China, Japan, and South Korea. Rectal sparganosis is an uncommon disease but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unusual and suspicious rectal submucosal tumors. We report a case of rectal sparganosis presenting as rectal submucosal tumor. We performed endoscopic submucosal dissection of the rectal submucosal tumor. The sparganosis was confirmed based on the presence of calcospherules in the submucosal layer on histological examination. Moreover, the result of the immunoglobulin G antibody test for sparganosis was positive but became negative after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Though rare, rectal sparganosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of rectal submucosal tumor-like lesions. This case suggests that physicians should make effort to exclude sparganosis through careful diagnostic approaches, including detailed history taking and serological tests for parasites. In this report, we aimed to highlight the clinical presentation of Sparganum infection as a rectal submucosal tumor.

Core tip: This rare case exhibited the rectal sparganosis presenting as rectal submucosal tumor. This is the first case of rectal sparganosis presenting as submucosal tumor that are treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Though rare, this case suggests that sparganosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of submucosal tumor-like lesions in gastrointestinal track.

- Citation: Kim JK, Baek DH, Lee BE, Kim GH, Song GA, Park DY. Endoscopic resection of sparganosis presenting as colon submucosal tumor: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(19): 4776-4780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i19/4776.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i19.4776

Human sparganosis is a rare infectious disease caused by Sparganum, a plerocercoid tape worm larva of the genus Spirometra, as first described by Manson in 1882[1]. Infections caused by sparganum have a worldwide distribution but are most common in Southeast Asia such as China, Japan, and South Korea[2-4]. In humans, it is accidentally acquired by ingestion of larva-containing water or by eating raw snakes and frogs. Sparganosis usually involves subcutaneous tissues and/or muscles of various parts of the body, but involvement of other sites such as the brain, eye, peritoneopleural cavity, urinary track, scrotum, and abdominal viscera has also been documented[5,6]. The larvae are commonly found in the chest, abdomen, urogenital organs, extremities, central nervous system, and orbital region[5]. The rectum is a distinctly rare site of the infection. The rectum is a distinctly rare site of the infection. Clinical manifestations of sparganosis are diverse, including headache, non-specific discomfort, vague pain, palpable mass, or even no symptoms[7]. The most common clinical manifestation is a migrating subcutaneous mass. Clinically and radiologically, the mass may mimic a neoplasm. Thus, it is difficult to diagnose preoperatively in most cases[2]. We report an interesting rare case of rectal sparganosis presenting as a submucosal tumor (SMT) treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). This report aimed to highlight the existence and clinical presentation of Sparganum infection, which is considered to be rare in South Korea. Moreover, this case report reveals an atypical picture where the larval form was not identified on gross examination of a resected specimen and the diagnosis was confirmed based on histological examination and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results.

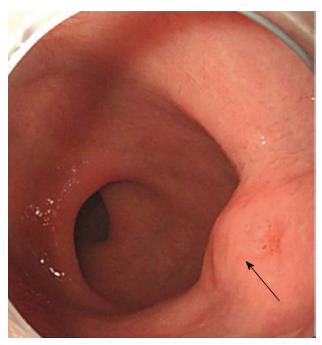

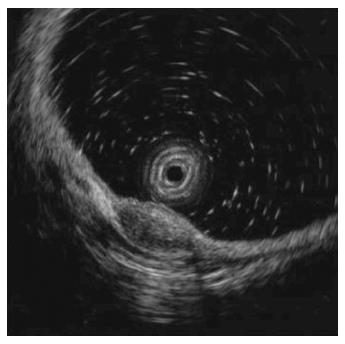

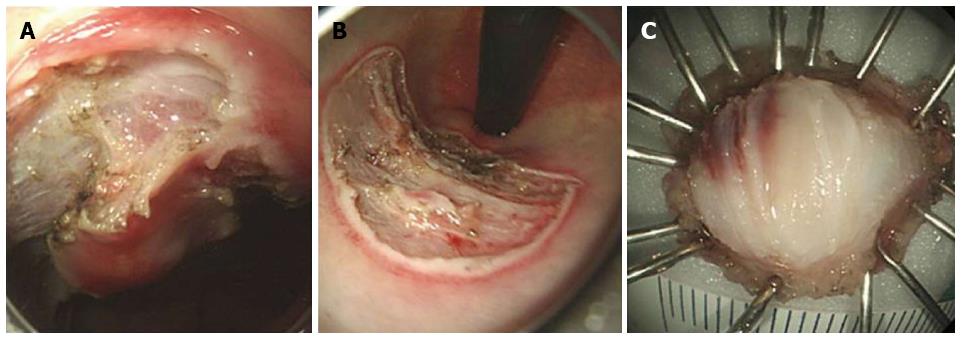

In October 2013, a 38-year-old Korean male was referred to gastroenterology team for evaluation of rectal SMT. His medical history was uneventful. His family history was unremarkable. In addition, review of system and physical examination results were unremarkable. The results of the laboratory tests, including complete blood count, liver function test, renal function test, and coagulation factor assay, were normal. Moreover, no eosinophilia was observed, and tumor markers and anti-HIV antibody levels were normal. Colonoscopy revealed a round SMT covered with normal mucosa, located 5 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealed a well-demarcated hypoechoic mass 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm in size chiefly located in the deep mucosa and submucosal layer (Figure 2). For complete and total resection of the lesion and accurate histological diagnosis, we performed an ESD (Figure 3A and B). Histological examination of the resected specimen revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation with foreign bodies associated with acute suppurative inflammation (Figure 4A). A high-resolution image showed some calcospherules in the submucosal layer (Figure 4B and C). The calcospherules are characteristic structures that reveal previous parasitic infection. Subsequently, immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody tests for cysticercosis, paragonimiasis, clonorchiasis, and sparganosis were performed, and the results were positive only for sparganosis. Although the gross examination of the excised tissue did not reveal any larval forms, the diagnosis was confirmed based on histological examination and ELISA results. We reevaluated the patient’s medical history. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that he had enjoyed eating organic vegetables. We suggest that his dietary habit was the route of the infection. No additional therapy such as antiparasitic medication or surgery was administered. Thirteen months after the ESD, follow-up colonoscopy revealed only the presence of a scar at the site of the ESD, and chest radiography and abdominal computed tomography did not reveal any additional abnormal findings. Moreover, the result of the IgG antibody test for sparganosis became negative after the ESD. He was doing well at 24 mo of follow-up.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of sparganosis presenting as rectal SMT. Human sparganosis is a rare infectious disease caused by Sparganum, a plerocercoid tapeworm larva of the genus Spirometra. Spargana larvae can be found in any part of the human body and have a preference for subcutaneous involvement and migration. In the extramammary organs, sparganosis most frequently manifests as a migrating subcutaneous nodule and presents clinically with vague or indeterminate symptoms.

Infections caused by sparganum have a worldwide distribution but are most common in Southeast Asia such as China, Japan, and South Korea. The most common route of infection is via ingestion of contaminated water containing procercoids, which can penetrate into the intestine and migrate to the muscle or subcutaneous tissue. The second route is from ingestion of raw or partially cooked frogs, snakes, fish, and chickens. The third route of infection may be from poultice applications infested with cyclops containing procercoids and are utilized for open wounds or the eyes[8]. Economic development and advancement in sanitation have influenced the routes, sites, and latent period of the infection. In our case, the patient denied eating raw meat or fish, including snakes and frogs. In addition, he had never traveled in Southeast Asia such as China, and Japan. Instead, he had enjoyed eating organic vegetables during his lifetime. We assume that the route of his infection was larvae from organic vegetables.

Sparganosis as a usual practice is diagnosed after the surgical removal of the worm from the site of inflammation. Although the larvae are decimated, the characteristic pathological findings of the chronic granulomatous inflammation with central necrosis and calcospherules can be helpful for diagnosis. However, in cases for which the feasibility of surgery is limited, surrogate diagnostic methods such as ELISA for sparganum in relation to a relevant history of exposure can be used[9]. ELISA performed for sparganum-specific IgG is highly sensitive and specific. Serum ELISA has 85.7% sensitivity and 95.7% specificity[6]. Negative ELISA results after surgical removal predict successful treatment of human sparganosis, but persistent positive reaction strongly suggests incomplete removal of the worm[8]. In our case where the gross examination of the excised tissue did not reveal any larval forms, the diagnosis was confirmed based on the histological examination and ELISA results. The negative ELISA result for sparganosis after ESD also strongly supported our diagnosis.

The definitive treatment of sparganosis is the surgical removal of larvae. However, when it cannot be removed surgically such as in multiorgan infection, drug therapy with praziquantel can be administered. However, many case reports showed that drug therapy with praziquantel did not have a favorable outcome and had high recurrence rates[10]. In our case, we did not administer praziquantel after ESD, the patient was doing well without recurrence for 24 mo after the ESD.

In conclusion, this is the first case of rectal sparganosis presenting as SMT. Furthermore, ESD performed to remove this parasite lesion is the first case. Though rare, rectal sparganosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of rectal SMT-like lesions. This case suggests that physicians should make effort to exclude sparganosis through careful diagnostic approaches, including detailed history taking and serological tests for parasites. Although the ESD is a rather uncommon way in order to treat sparganosis, ESD can be considered for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes like our case. In cases in which the rectal sparganosis is confined to the deep mucosa and/or submucosa on EUS and other sites are free of the disease, endoscopic resection with close follow-up should be considered as an alternative treatment modality.

38-year-old man with no significant medical history underwent colonoscopy for screening of the lower digestive tract. A rectal submucosal tumor was detected on 5 cm from the anal verge.

The patient had no symptom.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealed a hypoechoic mass chiefly located in the deep mucosa and submucosal layer, which could be seen in the context of rectal neuroendocrine tumor, rectal tonsil, lymphoma, or chronic granulomatous inflammation.

Laboratory data were within normal range with the exception of positive immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody tests for sparganosis.

Colonoscopy revealed a round submucosal tumor covered with normal mucosa, located 5 cm from the anal verge. Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a well-demarcated hypoechoic mass 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm in size chiefly located in the deep mucosa and submucosal layer.

The pathologic features of the resected specimen revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation with foreign bodies associated with acute suppurative inflammation and some calcospherules in high-resolution image.

The patient underwent rectal endoscopic submucosal dissection for both diagnostic and therapeutic purpose.

Human sparganosis is a rare infectious disease caused by Sparganum, a plerocercoid tapeworm larva of the genus Spirometra. Sparganosis usually involves subcutaneous tissues and/or muscles of various parts of the body, but rectal involvement presenting as submucosal tumor has not been documented.

A submucosal tumor is defined as any intramural growth under the mucosa, where etiology cannot readily be determined by endoscopy. EUS can be of help to make a diagnosis.

Physicians should consider sparganosis in the differential diagnosis of rectal submucosal tumor-like lesions. And detailed history taking and serological tests for parasites can also be helpful in diagnosis.

This article is very interesting from the point of the parasitic disease because rectal sparganosis is an uncommon and rare. Furthermore, endoscopic submucosal dissection performed to remove this parasite lesion was probably the first case.

| 1. | Cook GC, Zumla AI. Manson’s tropical diseases. 22nd ed. London: Saunders 2008; . |

| 2. | Cho SY, Bae JH, Seo BS. Some Aspects Of Human Sparganosis In Korea. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1975;13:60-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sparks AK, Neatie RC, Cannor DH. Sparganosis. Pathology of tropical and extraordinary disease, 1st ed. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1976; 534-538. |

| 4. | Cummings TJ, Madden JF, Gray L, Friedman AH, McLendon RE. Parasitic lesion of the insula suggesting cerebral sparganosis: case report. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:206-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mineura K, Mori T. Sparganosis of the brain. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:588-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim H, Kim SI, Cho SY. Serological Diagnosis Of Human Sparganosis By Means Of Micro-ELISA. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1984;22:222-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mueller JF. The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol. 1974;60:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chiba T, Yasukochi Y, Moroi Y, Furue M. A Case of Sparganosis mansoni in the Thigh: Serological Validation of Cure Following Surgery. Iran J Parasitol. 2012;7:103-106. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Walker MD, Zunt JR. Neuroparasitic infections: cestodes, trematodes, and protozoans. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:262-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chai JY, Yu JR, Lee SH, Kim SI, Cho SY. Ineffectiveness of praziquantel treatment for human sparganosis (A case report). Seoul J Med. 1988;29:397-399. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Huang CT, Lee HW, Mori H, Reinehr R, Wang BM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S