Published online Apr 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.4062

Peer-review started: October 16, 2015

First decision: November 5, 2015

Revised: November 30, 2015

Accepted: December 30, 2015

Article in press: December 30, 2015

Published online: April 21, 2016

Processing time: 171 Days and 9.1 Hours

Anti-androgen therapy is the leading treatment for advanced prostate cancer and is commonly used for neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment. Bicalutamide is a non-steroidal anti-androgen, used during the initiation of androgen deprivation therapy along with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist to reduce the symptoms of tumor-related flares in patients with advanced prostate cancer. As side effects, bicalutamide can cause fatigue, gynecomastia, and decreased libido through competitive androgen receptor blockade. Additionally, although not as common, drug-induced liver injury has also been reported. Herein, we report a case of hepatotoxicity secondary to bicalutamide use. Typically, bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity develops after a few days; however, in this case, hepatic injury occurred 5 mo after treatment initiation. Based on this rare case of delayed liver injury, we recommend careful monitoring of liver function throughout bicalutamide treatment for prostate cancer.

Core tip: This case report describes a 62-year-old man with prostate cancer who experienced delayed liver injury after bicalutamide therapy. In previous case reports on bicalutamide-induced liver injury, liver failure occurred shortly after bicalutamide therapy initiation. However, in this case, liver injury occurred 5 mo after bicalutamide treatment initiation. Therefore, our case emphasizes that liver function measurements should be monitored from baseline for at least the first 6 mo of therapy, and then periodically during the entire period of treatment with bicalutamide.

- Citation: Yun GY, Kim SH, Kim SW, Joo JS, Kim JS, Lee ES, Lee BS, Kang SH, Moon HS, Sung JK, Lee HY, Kim KH. Atypical onset of bicalutamide-induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(15): 4062-4065

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i15/4062.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.4062

Prostate neoplasms represent the second most common reason for male cancer-related mortality in the United States[1]. Mean age at diagnosis is 72 years; the condition is therefore called an “old man’s” disease. The 5-year overall survival rates have been estimated to be 92%-95% for localized, 80%-83% for locally advanced, and 29% for metastatic disease. In metastatic prostate cancer, anti-androgen therapy is the chief treatment. More import role of anti-androgen therapy is the neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy in the management of less advanced cancers[2].

Bicalutamide is a non-steroidal anti-androgen agent frequently administered during the initiation of androgen deprivation therapy along with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist; it relieves the flare symptoms in patients with advanced prostate cancer. The frequent drug-induced toxicities caused by bicalutamide are hot flashes, gynecomastia, and breast pain[3]. Liver function test abnormalities, particularly in elevated transaminases, are also seen in bicalutamide use. To our knowledge, there are currently only four previous reports on bicalutamide-induced liver injury worldwide, with no previous case reported in Korea. In these previous cases, the liver function impairments were typically transient and occurred within a few days of bicalutamide use[2,4-6].

In this case report, we present an uncommon case of delayed liver injury after bicalutamide therapy, showing prolonged liver dysfunction maintained for approximately 2 mo. This is the first description of bicalutamide-induced liver injury in a Korean patient.

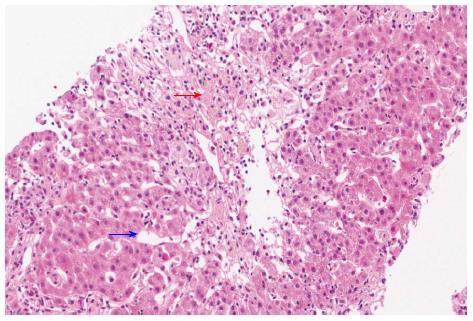

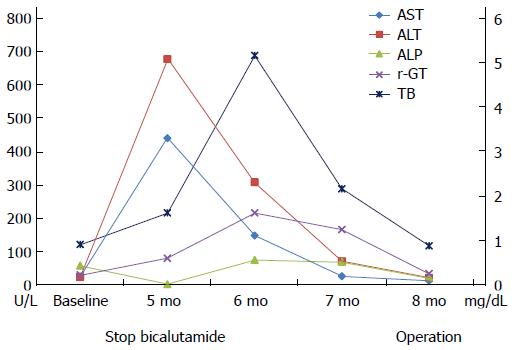

A 62-year-old South Korean man who was diagnosed with prostate cancer (T2N0M0; Gleason score 6; initial prostate-specific antigen, 6.75 ng/mL) presented with jaundice for a few days. He had been orally taking 100 mg bicalutamide daily for 19 wk as neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to presentation. He did not admit to use of illegal drugs or alcohol. Physical examination revealed scleral icterus. Blood work revealed acute liver dysfunction with alanine aminotransferase, 677 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 440 U/L; and international normalized ratio, 1.17. The total bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and alkaline phosphatase levels were 1.62 mg/dL, 80 U/L, and 87 U/L, respectively. The international normalized ratio was in the normal range during the entire period. He had normal baseline laboratory results at the initiation of bicalutamide administration. The result for hepatitis A immunoglobulin M was negative. Hepatitis B surface antigen was negative. Hepatitis C RNA was undetectable. The results for hepatitis E immunoglobulin M and G were also negative. On the other hand, the hepatitis B surface antibody was positive. Other etiologies like autoimmune disease, drugs, common toxins, and copper or iron-induced insult were considered. However, the antibodies for anti-mitochondrial, antinuclear, and anti-smooth muscle were negative, and the serum copper, ceruloplasmin, and 24-h urine copper levels were in the normal ranges. The modified Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method scale score was 8. These findings strongly suggested drug-induced liver injury. Abdominal CT showed non-specific findings, whereas liver biopsy revealed acute intrahepatic cholestasis in zone 3 and sinusoidal dilation with moderate lobular inflammation (Figure 1), suggesting liver injury caused by androgen, estrogen, or glucocorticoid administration.

As a result, bicalutamide was immediately withdrawn, and the patient was started on 75 mg/d biphenyl-dimethyl-dicarboxylate and 300 mg/d ursodeoxycholic acid. Laboratory abnormalities reduced with alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels of 11 U/L and 21 U/L, respectively, after 12 wk. Consequently, the patient underwent radical prostatectomy (Figure 2).

Several patterns of liver injury can occur secondary to many drugs, including cholestasis, hepatitis, and mixed-form injuries. Such drug-induced liver injury is usually divided into idiosyncratic and intrinsic reactions depend on the predictability and dose dependency. Intrinsic hepatotoxicity is dose dependent and can be predicted once a specific threshold amount has been absorbed. Conversely, idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity is dose independent and is subsequently unpredictable[2,7-10].

Liver biopsy is not routinely performed for evaluating drug-induced liver injury. However, it provides the opportunity to determine the form of injury, which may help confirm or exclude drug-induced liver injury, along with characterizing the distribution and severity of injury in the liver[11]. In this case, our patient underwent liver biopsy, which indicated drug-induced liver injury (e.g., erythromycin, estrogen, androgen, diazepam, diphenylhydantoin, glucocorticoid, thioguanine, or azathioprine-induced injury). Owing to the rarity of bicalutamide-induced liver toxicity, no specific pathologic findings have been described, and our findings may hence provide a basis for the diagnosis of bicalutamide-induced liver injury.

Bicalutamide is an orally active non-steroidal anti-androgen. It competitively antagonizes the actions of androgens of both testicular and adrenal origin at the receptor level, thereby preventing the spread of prostate cancer[12]. Unlike steroidal anti-androgens (e.g., cyproterone acetate), non-steroidal anti-androgens (e.g., bicalutamide, nilutamide, and flutamide) do not suppress testosterone production and provides a better quality of life over castration. Among the non-steroidal anti-androgens, flutamide has been established to induce liver injury and cause mild aminotransferase elevation in 42%-62% of patients[13].

However, while an article search for case reports of non-steroidal anti-androgens revealed many cases of flutamide-induced liver injury, cases of bicalutamide toxicity were rare. In four previously reported cases of bicalutamide-induced liver injury, the injury occurred after receiving 50 mg/d orally for 2 d, 50 mg/d orally for 4 d, 50 mg/d orally for 3 mo, and 150 mg/d orally for 3 wk. Of these, two patients died as a result of fulminant hepatic failure while the other two patients showed clinical and serological improvement within days[2,4-6]. These previous reports suggest that the possible mechanism of bicalutamide-induced liver injury comprise direct hepatotoxicity and idiosyncratic reaction. Initially, our patient was first treated in the urology department where he received 100 mg bicalutamide daily. He developed liver injury after daily bicalutamide use for 19 wk, but slowly showed improved liver function 12 wk after ceasing medication use. The higher daily dose (100 mg), compared to that administered to patients described in the previous case reports (50 mg), and may be associated with a dose-response effect. On the other hand, the delayed liver injury may indicate an idiosyncratic reaction, because of the unpredictable latency. Irrespective of the mechanism, potentially life-threatening and clinically significant liver injury can result from the use of bicalutamide.

Therefore, immediate recognition and stopping bicalutamide is vital to avoid severe complications such as fulminant hepatitis. Liver function tests should be regularly conducted during and after bicalutamide administration.

Actually, the patient described herein was referred to our department from the urology department 5 mo after bicalutamide treatment initiation. The exact time at which bicalutamide-induced liver injury occurred may be unclear, because liver enzyme measurements were not followed at the urology department. This case emphasizes that liver function measurements should be checked from the baseline for at least the first 6 mo of treatment, and then regularly during the entire period of treatment with bicalutamide.

A 62-year-old South Korean man with prostate cancer (T2N0M0; Gleason score 6) presented with jaundice for a few days.

Physical examination revealed scleral icterus.

Viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and metastasis of prostate cancer to the liver are differential diagnoses.

The aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, total bilirubin, and international normalized ratio levels were 440 U/L, 677 U/L, 87 U/L, 80 U/L, 1.62 mg/dL, and 1.17, respectively.

Abdominal CT showed non-specific findings.

Liver biopsy suggested liver injury caused by androgen, estrogen, or glucocorticoid administration.

Bicalutamide was immediately discontinued.

There are only four previous case reports on bicalutamide-induced liver injury. In these previous cases, hepatic failure occurred within a few days of bicalutamide use.

There are no unusual terms that require explanation.

Although rare, clinically significant and potentially life-threatening liver injury can result from the use of bicalutamide. Prompt recognition and discontinuation of bicalutamide is necessary to avoid serious complications such as fulminant hepatitis. Liver function measurements should be monitored from baseline for at least the first 6 mo of therapy, and then periodically during the entire period of treatment with bicalutamide.

The authors describe a rare case of bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity, a 62 year-old Korean man with prostate cancer was administered with bicalutamide as a neoadjuvant chemotherapy and he experienced delayed liver injury. This is an interesting case study with valuable insights for the monitoring of liver enzymes in patients being treated with bicalutamide.

| 1. | Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8789] [Cited by in RCA: 9584] [Article Influence: 798.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Castro Beza I, Sánchez Ruiz J, Peracaula Espino FJ, Villanego Beltrán MI. Drug-related hepatotoxicity and hepatic failure following combined androgen blockade. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10:591-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kaisary AV. Current clinical studies with a new nonsteroidal antiandrogen, Casodex. Prostate Suppl. 1994;5:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dawson LA, Chow E, Morton G. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with bicalutamide. Urology. 1997;49:283-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | O’Bryant CL, Flaig TW, Utz KJ. Bicalutamide-associated fulminant hepatotoxicity. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:1071-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hussain S, Haidar A, Bloom RE, Zayouna N, Piper MH, Jafri SM. Bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: A rare adverse effect. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:266-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kackar RR, Desai HG. Hepatic failure with flutamide. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:149-150. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wysowski DK, Freiman JP, Tourtelot JB, Horton ML. Fatal and nonfatal hepatotoxicity associated with flutamide. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:860-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wysowski DK, Fourcroy JL. Flutamide hepatotoxicity. J Urol. 1996;155:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stephens C, Andrade RJ, Lucena MI. Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:286-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kleiner DE. Liver histology in the diagnosis and prognosis of drug-induced liver injury. Clinical Liver Disease. 2014;4:12-16. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kolvenbag GJ, Blackledge GR, Gotting-Smith K. Bicalutamide (Casodex) in the treatment of prostate cancer: history of clinical development. Prostate. 1998;34:61-72. [PubMed] |

| 13. | McLeod DG. Tolerability of Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens in the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Oncologist. 1997;2:18-27. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chiang TA, Jin B, Jaeschke H, Jamall IS, Kim Y, Thomopoulos KC S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM