Published online Mar 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i12.3404

Peer-review started: September 19, 2015

First decision: October 14, 2015

Revised: November 9, 2015

Accepted: December 30, 2015

Article in press: December 30, 2015

Published online: March 28, 2016

Processing time: 187 Days and 4.2 Hours

AIM: To study the intrahepatic expression of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) in chronic hepatitis B patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma.

METHODS: A total of 33 chronic hepatitis B patients (mean age of 40.3 ± 2.5 years), comprising of 14 HBeAg positive and 19 HBeAg negative patients; and 13 patients with hepatitis B virus related hepatocellular carcinoma (mean age of 49.6 ± 4.7 years), were included in our study. Immunohistochemical staining for HBcAg and HBsAg was done using standard streptavidin-biotin-immunoperoxidase technique on paraffin-embedded liver biopsies. The HBcAg and HBsAg staining distributions and patterns were described according to a modified classification system.

RESULTS: Compared to the HBeAg negative patients, the HBeAg positive patients were younger, had higher mean HBV DNA and alanine transaminases levels. All the HBeAg positive patients had intrahepatic HBcAg staining; predominantly with “diffuse” distribution (79%) and “mixed cytoplasmic/nuclear” pattern (79%). In comparison, only 5% of the HBeAg-negative patients had intrahepatic HBcAg staining. However, the intrahepatic HBsAg staining has wider distribution among the HBeAg negative patients, namely; majority of the HBeAg negative cases had “patchy” HBsAg distribution compared to “rare” distribution among the HBeAg positive cases. All but one patient with HCC were HBeAg negative with either undetectable HBV DNA or very low level of viremia. Intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg were seen in 13 (100%) and 10 (77%) of the HCC patients respectively. Interestingly, among the 9 HCC patients on anti-viral therapy with suppressed HBV DNA, HBcAg and HBsAg were detected in tumor tissues but not the adjacent liver in 4 (44%) and 1 (11%) patient respectively.

CONCLUSION: Isolated intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg can be present in tumors of patients with suppressed HBV DNA on antiviral therapy; that may predispose them to cancer development.

Core tip: This study described the distributions and patterns of intrahepatic hepatitis B core antigen and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in patients with chronic hepatitis B using a novel, modified classification system. The HBeAg negative patients were found to have intense HBsAg in liver tissues despite their lower serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels. For those with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), we observed high rate of HBV antigen detection in tumor tissues, but not in adjacent non-tumor livers, especially among those with optimal serum HBV DNA suppression. These data support that HCC can be derived from clonal expansion of infected hepatocytes with high carcinogenic potentials and selective resistance to antiviral agents.

- Citation: Safaie P, Poongkunran M, Kuang PP, Javaid A, Jacobs C, Pohlmann R, Nasser I, Lau DT. Intrahepatic distribution of hepatitis B virus antigens in patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(12): 3404-3411

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i12/3404.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i12.3404

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has a worldwide distribution affecting more than 240 million individuals[1,2]. It accounts near to 1 million deaths annually through complications such as liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[3,4]. Clinical outcomes of HBV depend on the interaction between viral and host-specific factors.

Hepatitis B viral proteins include a structural nucleocapsid core protein (HBcAg), an envelope protein (HBsAg), and a soluble nucleocapsid protein (HBeAg)[5]. Serum HBeAg is a surrogate marker for active hepatitis B virus replication in hepatocytes[6]. HBcAg is an intracellular antigen that is detectable either in the nucleus or cytoplasm of HBV-infected hepatocytes[7]. There are reports that high nuclear expression of HBcAg reflects high level of circulating HBV DNA and normal alanine transaminases (ALT) level as seen in the “immune tolerance phase” of hepatitis B[8-10]. In contrast, the cytoplasmic expression reflects a lower level of circulating HBV DNA, but increased hepatocellular damage with higher ALT level during the “immune clearance phase”[11-13]. A study also suggested that the membranous expression of HBsAg relates closely to active viral replication[13]. However, immunohistochemical expression of HBcAg, HBsAg and its relationship to virological and histological activities has been inconsistent and limited, especially in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B and HBV related HCC[16,17]. The lack of a standardized system to describe the intrahepatic HBV antigen distribution may contribute to the inconsistent findings[18].

In this study, we developed a modified classification system that allows consistency in the description of both the distributions and patterns of intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg. We applied the classification system to examine the HBcAg and HBsAg distributions in tissues from patients with HBeAg positive (+ve) and HBeAg negative (-ve) chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Since patients with optimal HBV DNA suppression on antiviral therapy are still at risk for HCC, we also examined the patterns of HBcAg and HBsAg in tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues among HCC patients with and without antiviral treatment.

Liver biopsies from a total of 33 patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and 13 patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma were included in the study. Fifty chronic hepatitis B cases were initially identified from our recent pathology database. Patients with HCV, HDV and HIV co-infection and inadequate biopsy size (< 2 cm) were subsequently excluded. Of the 33 HBsAg positive patients, 14 were HBeAg positive and 19 were HBeAg negative. None of the CHB patients received antiviral or immunosuppressive therapy prior to liver biopsy. The 13 HCC patients were selected from our tumor clinic database. Patients with HCV, HDV, and HIV coinfection were excluded. Nine of the 13 (69%) HCC patients were on antiviral therapy prior to the development of liver cancer. Our liver pathologists reviewed histological scoring and invasiveness of HCC on all these 46 cases consistently. All patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from our electronic medical records at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

The histological diagnosis was established using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and masson trichrome stains of formalin fixed paraffin-embedded liver tissue. Hepatic fibrosis was graded by our liver histopathologists according to the Metavir system on a 5-point scale between 0 and 4.

HBeAg, anti-HBe, anti-HCV were tested by enzyme immunoassay and HBV DNA quantification was performed using the Cobas Ampliprep/Cobas Taqman HBV at the Molecular lab. Analysis of sections of paraffin-embedded liver biopsies was performed using a previously reported procedure[7].

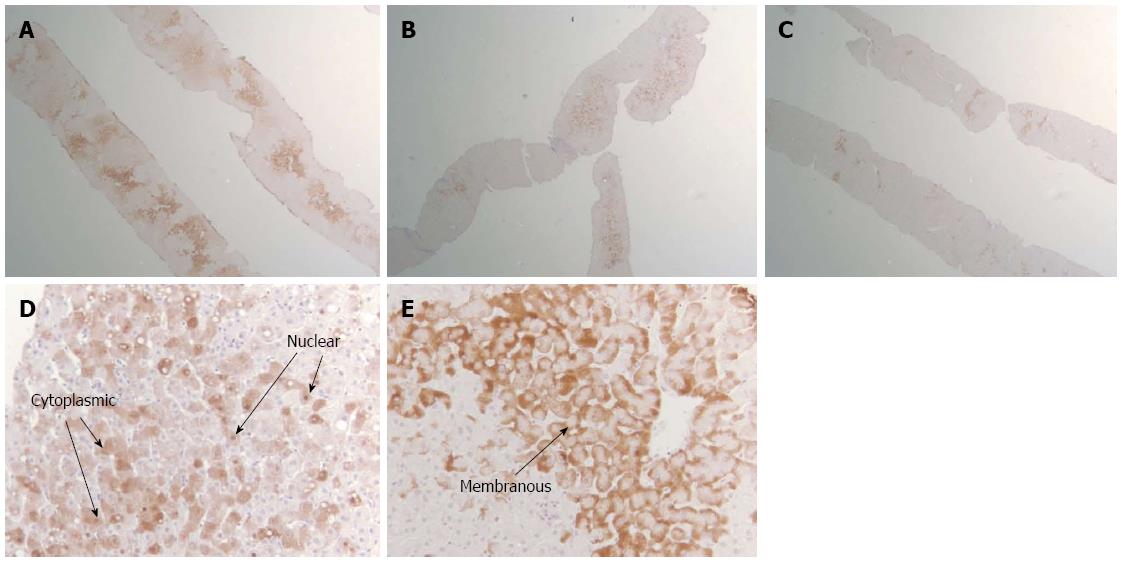

Using standard streptavidin-biotin-immunoperoxidase technique, immunohistochemical staining for HBcAg and HBsAg was done[19] in our laboratory at BIDMC. Briefly, it involves 4 major steps: deparaffinization of tissue, antigen retrieval, tissue permeabilization and immunostaining. The distribution and patterns of intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg was uniformly recorded. We developed a clinically relevant, modified classification system to analyze the HBsAg and HBeAg patterns as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| HBcAg | HBsAg | |

| Distribution | ||

| Diffuse | Contiguous without skip zones | Contiguous without skip zones |

| Either in clusters or single cells | Either in clusters or single cells | |

| Patchy | < 50% area with skip zones | < 50% area with skip zones |

| Either in clusters or single cells | Either in clusters or single cells | |

| Rare | Occasional area of entire field | Occasional area of entire field |

| Either in clustersor single cells | Either in clustersor single cells | |

| Pattern | -Nuclear | -Membranous |

| -Cytoplasmic | -Cytoplasmic |

HBeAg positive patients were younger than the HBeAg negative subjects. The gender distributions were not different between the groups with Asian males accounting for the majority of patients in both groups. Mean HBV DNA and ALT levels were higher in the HBeAg positive than the HBeAg negative patients. However, the histological characteristics were not different between the two groups. Over 90% of the patients in each group had mild to moderate grade 1-2 inflammation. Advanced Stage 3-4 hepatic fibrosis was present in 29% and 10% of the HBeAg positive and negative patients respectively (Table 2).

| Variables | HBeAg-positive (n = 14) | HBeAg-negative (n = 19) |

| Mean age in years | 38.5 | 42 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 13 (93) | 10 (53) |

| White | 1 (7) | 1 (5) |

| African/African American | 0 (0) | 7 (37) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Male: female, n | 11:3 | 13:6 |

| HBV DNA (IU/mL), mean | 28 million | 7.3 million |

| ALT (U/L), mean | 124 | 33 |

| Inflammatory grades | ||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| 1-2 | 13 (93) | 18 (95) |

| 3-4 | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Fibrosis stage | ||

| 0 | 3 (21) | 10 (53) |

| 1-2 | 7 (50) | 7 (37) |

| 3-4 | 4 (29) | 2 (10) |

Intrahepatic staining of HBcAg was seen in all 14 HBeAg positive patients with predominantly ‘diffuse’ distribution (79%) and “mixed cytoplasmic/nuclear” pattern (79%). Among the 19 HBeAg-negative patients, only one (5%) had positive intrahepatic HBcAg. It was ‘rare’ with mixed cytoplasmic/nuclear pattern. Intrahepatic HBsAg was seen in all the patients irrespective of their HBeAg status and was predominantly cytoplasmic (> 70%) in both groups. HBeAg negative patients actually had stronger intrahepatic HBsAg distributions. Majority (85%) of the HBeAg negative cases had either diffuse or patchy HBsAg distribution compared to 50% among the HBeAg positive cases (Table 3).

| Variables | HBeAg-positive (n = 14) | HBeAg-negative (n = 19) | ||

| Distribution, | HBcAg | HBsAg | HBcAg | HBsAg |

| Diffuse | 11 (79) | 5 (36) | 0 (0) | 6 (32) |

| Patchy | 1 (7) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 10 (53) |

| Rare | 2 (14) | 7 (50) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) |

| Pattern | ||||

| Cytoplasmic (+) | 1 (7) | - | 0 (0) | - |

| Nuclear (+) | 2 (14) | - | 0 (0) | - |

| Mixed: Cyto/nuclear | 11 (79) | - | 1 (5) | - |

| Cytoplasmic (+) | - | 11 (79) | - | 14 (74) |

| Membranous (+) | - | 1 (7) | - | 0 (0) |

| Mixed: Cyto/memb | - | 2 (14) | - | 5 (26) |

All 13 patients (9 males and 4 females) were Asian patients with age range between 25 and 69 years. All but one patient were HBeAg negative. Eight of Twelve (67%) HBeAg negative HCC patients had HBcAg in their adjacent non-tumor tissues. This is in distinct contrast to the HBeAg negative CHB patients without cancer, where only 1/19 (5%) had positive HBcAg. However, HBsAg in the adjacent non-tumor tissues was less prevalent among patients with HCC (67%) compared to the HBeAg negative CHB patients without cancer (100%) (Table 4).

| Variables | HCC group on anti-viral therapy (n = 9) | HCC group on no therapy (n = 4) |

| Mean age ± SD, yr | 53.2 ± 8.5 | 46.5 ± 20.5 |

| Male: female | 7:2 | 2:2 |

| HBeAg negative | 8/9 | 4/4 |

| Undetectable HBV DNA | 8/9 | 0/4 |

| Cirrhosis | 4/9 | 0/4 |

| Invasive HCC | 3/9 | 4/4 |

| Tumor: | ||

| Well differentiation | 6/9 | 1/4 |

| Moderate differentiation | 3/9 | 3/4 |

| Intrahepatic HBcAg staining | ||

| (+) Only in tumor tissues | 4/9 | 1/4 |

| (+) Only in non-tumor tissues | 3/9 | 1/4 |

| (+) Both in tumor and non-tumor tissues | 2/9 | 2/4 |

| Intrahepatic HBsAg staining | ||

| (+) Only in tumor tissues | 1/9 | 0/4 |

| (+) Only in non-tumor tissues | 3/9 | 2/4 |

| (+) Both in tumor and non-tumor tissues | 3/9 | 1/4 |

Patients with HCC were further classified into two groups based on whether they were on anti-viral therapy prior to the diagnosis of HCC. All four HCC patients who were not on anti-viral therapy had invasive carcinoma and replicative serum HBV DNA. In contrast, 8 of 9 (89%) patients on anti-viral therapy had undetectable serum HBV DNA, and only 3 developed invasive carcinoma.

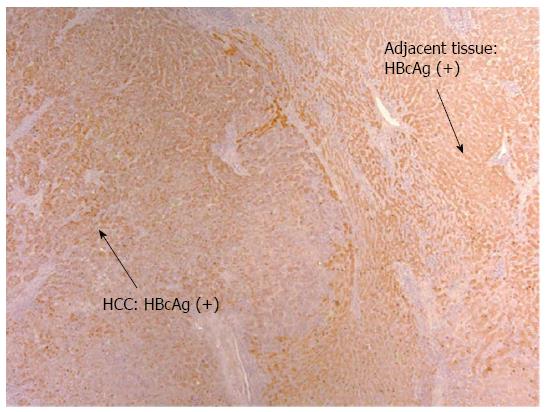

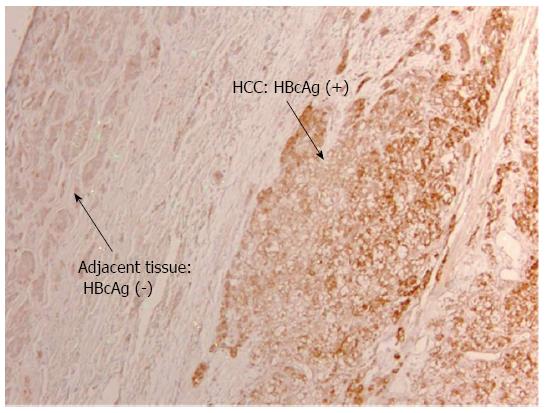

Detection of HBV Antigens in HCC patients on anti-viral therapy: Despite on antiviral therapy, intrahepatic HBcAg was detected in all nine patients in the treatment group. The majority had diffuse distribution. Figure 2 illustrated diffuse HBcAg in both tumor and adjacent tissue of a patient. Interestingly, 4 (44%) patients with suppressed serum HBV DNA were found to have diffuse distribution of HBcAg only in the tumor but not in the adjacent liver (representative case shown in Figure 3). Intrahepatic HBsAg was detected in seven of nine (78%) patients. The majority had patchy distribution. Only one of the nine (11%) patients had HBsAg detected in the tumor tissue alone (Table 4).

Detection of HBV Antigens in HCC patients not on anti-viral therapy: Intrahepatic staining of HBcAg was seen all four patients with only one having patchy HBcAg present in the tumor tissue alone. Intrahepatic HBsAg was detected in three of four patients with none presenting only in the tumor tissue alone. Intrahepatic staining of both HBcAg and HBsAg in tumor tissues was seen only in one patient (Table 4).

In this study, we sought to examine the intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg distribution and patterns using a standardized, modified classification system in patients with chronic hepatitis B and in those with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma.

HBeAg that is considered to be a marker of HBV replication and infectivity; is usually associated with high levels of serum HBV DNA[5,20]. In our study, we found HBeAg positive patients to be younger, had higher serum levels of HBV DNA and ALT when compared to the HBeAg negative patients. These observations are in concordance with previous reports[21-23].

The presence of intrahepatic HBcAg in 100% of our HBeAg positive subjects with high level of viremia confirm the previous studies that the presence of HBcAg in hepatocytes serves as as a marker of viral replication[24,25]. The prevalence of intrahepatic HBcAg expression in HBeAg negative patients has been inconsistent and was reported between 0% and 90%[26-31]. In our current study, we detected HBcAg in only 5% of the HBeAg negative patients. Even though intrahepatic HBcAg expression was infrequent in HBeAg negative CHB, its absence cannot exclude the presence of modest levels of HBV replication[18].

The mixed cytoplasmic/nuclear pattern of HBcAg staining in the majority of our HBeAg-positive patients correlates positively with the diffuse HBcAg distribution and high HBV DNA levels. These results are consistent with previous reports[7,8,13]. Among HBeAg-negative patients, only one had positive but rare distribution intrahepatic HBcAg. These results are consistent with previous reports that higher level of viral replication (or serum HBV DNA) is associated with diffuse distribution and mixed cytoplasmic/nuclear pattern of HBcAg[7,8,11,13,18,24,30].

In contrast to HBcAg, all patients had positive intrahepatic HBsAg regardless of their HBeAg status, and its distribution did not correlate with HBV DNA levels. In fact, HBeAg negative patients had more intense intrahepatic HBsAg distributions. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the increased accumulation of intracellular HBsAg during inactive viral replication is secondary to the diminished synthesis of HBcAg and, therefore, reduced export of HBsAg[32,33]. Both HBeAg positive and negative patients had predominantly cytoplasmic HBsAg pattern regardless of their serum HBV DNA levels. In the literature, either cytoplasmic or membranous expression of HBsAg had been associated with active viral replication[7,28]. We could not comment on the isolated membranous pattern for the majority of our patients had either cytoplasmic or mixed cytoplasmic, membranous HBsAg pattern.

HBcAg expressions have been thought to induce liver necroinflammation through HBV specific and non-specific T cells. Previous studies indicated that patients with predominantly nuclear expression of HBcAg had lower hepatocellular damage compared to those with predominantly cytoplasmic expression[21,22,34]. Studies from European and Asian population, however, reported no significant correlation between the patterns of HBcAg, HBsAg and hepatic injury[35-40]. Similarly, our study did not find a relationship between intrahepatic HBV antigen expression and histological activity in chronic hepatitis B. These inconsistent results may signify the complex interactions between the host and the hepatitis B virus.

Chronic hepatitis B is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) globally. Its risk factors include advanced age, male sex, HBV genotype, longer duration of infection, higher viral load, elevated ALT, presence of cirrhosis and co-infections[41,42]. It is known that the cumulative risk of HCC persists after the clearance of HBV DNA, HBeAg and HBsAg in CHB[43-45]. In this study, HCC patients were older (mean age, 49.6 ± 4.7 years) compared to those with chronic hepatitis B. The majority (92%) of our HCC patients were HBeAg negative, had undetectable HBV DNA on antiviral therapy and only 23% had underlying cirrhosis. These observations provided further evidence that HCC risk persists despite HBeAg seroclearance and optimal serum HBV DNA suppression. Detailed studies on the intrahepatic HBV antigens in HCC patients are limited. We detected intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg in 100% and 77% of our HCC patients respectively in spite of their undetectable serum HBV DNA and HBeAg negative status. These findings strongly suggest that HBV replication in HCC occurs more commonly than previously perceived by other studies[16,46-48]. Suzuki et al[48] reported 11.6/4.2% HBsAg/HBcAg in HCC and the highest reported was from Hsc et al and coworkers around 32/14.7% respectively.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the distribution or patterns of HBV-associated antigens in HCC patients based on treatment status. Perhaps the most significant observation in our study is the high rate of HBV antigen detection in tumor tissue alone, but not in adjacent non-tumor liver, among those with optimal HBV DNA suppression. We identified five of 9 (56%) of HCC patients with either HBcAg or HBsAg present only in tumor tissues despite prolonged nucleoside analogue treatment. These data may imply that these tumors were derived from clonal expansion of infected hepatocytes with high rate of proliferation, carcinogenic potentials and selective resistance to antiviral agents[49,50]. Our findings also support the possible mechanisms of HBV-induced carcinogenesis secondary to HBV DNA integration into host genome leading to potential activation of oncogenes and induction of genetic instability. For instance, protein HBx is reported to be involved in activation of numerous signaling pathways and cellular promoters and to host DNA mutations[51,52].

This study, while providing new observations on the potential mechanisms of HCC development, has a number of limitations. It is a retrospective study with especially patients with HCC referred from other health centers. Hence, details about other potential confounding factors of tumor development such as alcoholism and other environmental exposure were unavailable for the analyses. Lastly, the enrolled subjects are mostly Asians, and hence our findings should be confirmed with other populations.

In conclusion, the presence of intrahepatic HBcAg is associated with HBeAg positive status. Hepatocyte expression of diffuse, mixed (cytoplasmic/nuclear) expression of HBcAg correlates with serum HBV DNA levels, but not with the histological activity. Intrahepatic HBsAg was detected in all chronic hepatitis B patients regardless of their HBeAg status or levels of viremia. While intrahepatic HBcAg is rarely detectable in HBeAg negative chronic HBV patients, majority of the HBeAg negative patients with hepatocellular carcinoma had positive HBcAg even with optimal viral suppression. The presence of either HBcAg or HBsAg within tumor tissues of HCC patients on treatment may indicate that these tumors were derived from clonal expansion of infected hepatocytes with high carcinogenic potentials and drug resistance.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a globally prevalent liver disease that can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The outcome of the chronic HBV infection depends on both viral and host-specific factors. The disease outcomes have been correlated to serum HBV DNA levels and HBeAg status. Intra-hepatic distributions and localization patterns of viral antigens detected by immunohistochemistry could potentially provide additional prognostic values. In this study, the authors developed a modified classification system to characterize the expressions of HBV core antigen (HBcAg) and HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) in liver tissues of patients with chronic hepatitis B with and without HCC.

The authors observed a high rate of HBV antigen detection in tumor tissue alone, but not in adjacent non-tumor liver in HCC patients with optimal HBV DNA suppression. This raised the question of HBV DNA integration into host genome leading to potential activation of oncogenes, induction of genetic instability and antiviral drug resistance.

The authors developed a modified classification system to standardize the reporting of the intrahepatic distributions and patterns of HBcAg and HBsAg. The authors discovered distinct differences in the distributions of these antigens in HBeAg positive and HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B patients. Interestingly, authors observed variable HBV antigen expressions in the tumor tissues. These results provided insights into the potential mechanisms of disease persistence and carcinogenesis.

These findings open up new research study to confirm that these liver cancers were derived from clonal expansion of infected hepatocytes with high rate of proliferation, carcinogenic potentials and selective resistance to antiviral agents.

Immunohistochemical staining of liver tissues: it applies standard streptavidin-biotin-immunoperoxidase technique to identify the various proteins in the liver.

The author of this paper evaluated the distributions and patterns of intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg in patients with chronic hepatitis B using a novel, modified classification system. The HBcAg expression is associated with high levels of serum HBV DNA and HBeAg status. The extensive HBsAg distribution even in HBeAg negative patents with low level of viremia explains the persistence of hepatitis B. The distinct expressions of viral antigens in tumor tissues deserve further evaluations to understand the carcinogenesis of HBV.

| 1. | Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1118-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1700] [Cited by in RCA: 1725] [Article Influence: 78.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1728] [Cited by in RCA: 1714] [Article Influence: 59.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:S13-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 747] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1794] [Cited by in RCA: 1778] [Article Influence: 93.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 693] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen CJ, Yang HI, Iloeje UH. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels and outcomes in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:S72-S84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chu CM, Liaw YF. Intrahepatic expression of HBcAg in chronic HBV hepatitis: lessons from molecular biology. Hepatology. 1990;12:1443-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Serinoz E, Varli M, Erden E, Cinar K, Kansu A, Uzunalimoglu O, Yurdaydin C, Bozkaya H. Nuclear localization of hepatitis B core antigen and its relations to liver injury, hepatocyte proliferation, and viral load. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chu CM, Yeh CT, Chien RN, Sheen IS, Liaw YF. The degrees of hepatocyte nuclear but not cytoplasmic expression of hepatitis B core antigen reflect the level of viral replication in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:102-105. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chu CM, Liaw YF. Intrahepatic distribution of hepatitis B surface and core antigens in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatocyte with cytoplasmic/membranous hepatitis B core antigen as a possible target for immune hepatocytolysis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:220-225. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chu CM, Yeh CT, Sheen IS, Liaw YF. Subcellular localization of hepatitis B core antigen in relation to hepatocyte regeneration in chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1926-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hsu HC, Su IJ, Lai MY, Chen DS, Chang MH, Chuang SM, Sung JL. Biologic and prognostic significance of hepatocyte hepatitis B core antigen expressions in the natural course of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 1987;5:45-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim CW, Yoon SK, Jung ES, Jung CK, Jang JW, Kim MS, Lee SY, Bae SH, Choi JY, Choi SW. Correlation of hepatitis B core antigen and beta-catenin expression on hepatocytes in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: relevance to the severity of liver damage and viral replication. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1534-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hu KQ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implications. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:243-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Omata M, Afroudakis A, Liew CT, Ashcavai M, Peters RL. Comparison of serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and serum anticore with tissue HBsAg and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). Gastroenterology. 1978;75:1003-1009. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hsu HC, Wu TT, Wu MZ, Wu CY, Chiou TJ, Sheu JC, Lee CS, Chen DS. Evolution of expression of hepatitis B surface and core antigens (HBsAg, HBcAg) in resected primary and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in HBsAg carriers in Taiwan. Correlation with local host immune response. Cancer. 1988;62:915-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liaw YF, Chu CM, Lin DY, Sheen IS, Yang CY, Huang MJ. Age-specific prevalence and significance of hepatitis B e antigen and antibody in chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Taiwan: a comparison among asymptomatic carriers, chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol. 1984;13:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chu CM, Liaw YF. Immunohistological study of intrahepatic expression of hepatitis B core and E antigens in chronic type B hepatitis. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:791-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Werner M, Von Wasielewski R, Komminoth P. Antigen retrieval, signal amplification and intensification in immunohistochemistry. Histochem Cell Biol. 1996;105:253-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shi YH, Shi CH. Molecular characteristics and stages of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3099-3105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Manesis EK, Papatheodoridis GV, Sevastianos V, Cholongitas E, Papaioannou C, Hadziyannis SJ. Significance of hepatitis B viremia levels determined by a quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2261-2267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ramakrishna B, Mukhopadhya A, Kurian G. Correlation of hepatocyte expression of hepatitis B viral antigens with histological activity and viral titer in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: an immunohistochemical study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1734-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shao J, Wei L, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang LF, Li J, Dong JQ. Relationship between hepatitis B virus DNA levels and liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2104-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chu CM, Liaw YF. Membrane staining for hepatitis B surface antigen on hepatocytes: a sensitive and specific marker of active viral replication in hepatitis B. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:470-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim TH, Cho EY, Oh HJ, Choi CS, Kim JW, Moon HB, Kim HC. The degrees of hepatocyte cytoplasmic expression of hepatitis B core antigen correlate with histologic activity of liver disease in the young patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:279-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chu CJ, Hussain M, Lok AS. Quantitative serum HBV DNA levels during different stages of chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatology. 2002;36:1408-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hadziyannis SJ, Lieberman HM, Karvountzis GG, Shafritz DA. Analysis of liver disease, nuclear HBcAg, viral replication, and hepatitis B virus DNA in liver and serum of HBeAg Vs. anti-HBe positive carriers of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 1983;3:656-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mukhopadhya A, Ramakrishna B, Richard V, Padankatti R, Eapen CE, Chandy GM. Liver histology and immunohistochemical findings in asymptomatic Indians with incidental detection of hepatitis B virus infection. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:128-131. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Raihan R, Tabassum S, Nessa A, Jahan M, Al Mahtab M, Mohammad C, Kabir S, Kamal M, Aguilar JC. High HBcAg Expression in Hepatocytes of Chronic Hepatitis B Patients in Bangladesh. Age. 2012;25:32-39. |

| 30. | Son MS, Yoo JH, Kwon CI, Ko KH, Hong SP, Hwang SG, Park PW, Park CK, Rim KS. Associations of Expressions of HBcAg and HBsAg with the Histologic Activity of Liver Disease and Viral Replication. Gut Liver. 2008;2:166-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Uzun Y, Bozkaya H, Erden E, Cinar K, Idilman R, Yurdaydin C, Uzunalimoglu O. Hepatitis B core antigen expression pattern reflects the response to anti-viral treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:977-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chu CM, Shyu WC, Liaw YF. Immunopathology on hepatocyte expression of HBV surface, core, and x antigens in chronic hepatitis B: clinical and virological correlation. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:446-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ozaras R, Tabak F, Tahan V, Ozturk R, Akin H, Mert A, Senturk H. Correlation of quantitative assay of HBsAg and HBV DNA levels during chronic HBV treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2995-2998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Maini MK, Boni C, Lee CK, Larrubia JR, Reignat S, Ogg GS, King AS, Herberg J, Gilson R, Alisa A. The role of virus-specific CD8(+) cells in liver damage and viral control during persistent hepatitis B virus infection. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1269-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 651] [Cited by in RCA: 668] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Dusheiko G, Paterson A. Hepatitis B core and surface antigen expression in HBeAg and HBV DNA positive chronic hepatitis B: correlation with clinical and histological parameters. Liver. 1987;7:228-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lindh M, Horal P, Dhillon AP, Norkrans G. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels, precore mutations, genotypes and histological activity in chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Papatheodoridis GV, Manesis EK, Manolakopoulos S, Elefsiniotis IS, Goulis J, Giannousis J, Bilalis A, Kafiri G, Tzourmakliotis D, Archimandritis AJ. Is there a meaningful serum hepatitis B virus DNA cutoff level for therapeutic decisions in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection? Hepatology. 2008;48:1451-1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sari A, Dere Y, Pakoz B, Calli A, Unal B, Tunakan M. Relation of hepatitis B core antigen expression with histological activity, serum HBeAg, and HBV DNA levels. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sharma RR, Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Vasistha RK. Immunohistochemistry for core and surface antigens in chronic hepatitis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:16-19. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Zarski JP, Marcellin P, Cohard M, Lutz JM, Bouche C, Rais A. Comparison of anti-HBe-positive and HBe-antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B in France. French Multicentre Group. J Hepatol. 1994;20:636-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Samonakis DN, Koulentaki M, Coucoutsi C, Augoustaki A, Baritaki C, Digenakis E, Papiamonis N, Fragaki M, Matrella E, Tzardi M. Clinical outcomes of compensated and decompensated cirrhosis: A long term study. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:504-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Taylor BC, Yuan JM, Shamliyan TA, Shaukat A, Kane RL, Wilt TJ. Clinical outcomes in adults with chronic hepatitis B in association with patient and viral characteristics: A systematic review of evidence. Hepatology. 2009;49:S85-S95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Arase Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Someya T, Hosaka T, Sezaki H. Long-term outcome after hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Am J Med. 2006;119:71.e9-71.16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bréchot C, Degos F, Lugassy C, Thiers V, Zafrani S, Franco D, Bismuth H, Trépo C, Benhamou JP, Wands J. Hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with chronic liver disease and negative tests for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:270-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Yuen MF, Wong DK, Fung J, Ip P, But D, Hung I, Lau K, Yuen JC, Lai CL. HBsAg Seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in Asian patients: replicative level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1192-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Craxi A, Pasqua P, Giannuoli G, Di Stefano R, Simonetti RG, Pagliaro L. Tissue markers of hepatitis B virus infection in hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1984;31:55-59. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Hsu HC, Wu TT, Sheu JC, Wu CY, Chiou TJ, Lee CS, Chen DS. Biologic significance of the detection of HBsAg and HBcAg in liver and tumor from 204 HBsAg-positive patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1989;9:747-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Suzuki K, Uchida T, Horiuchi R, Shikata T. Localization of hepatitis B surface and core antigens in human hepatocellular carcinoma by immunoperoxidase methods. Replication of complete virions of carcinoma cells. Cancer. 1985;56:321-327. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Fernández-Rodríguez CM, Gutiérrez-García ML. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2014;5:175-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Gordon SC, Lamerato LE, Rupp LB, Li J, Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Spradling PR, Teshale EH, Vijayadeva V, Boscarino JA. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection and development of hepatocellular carcinoma in a US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:885-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kwon H, Lok AS. Does antiviral therapy prevent hepatocellular carcinoma? Antivir Ther. 2011;16:787-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Yu LH, Li N, Cheng SQ. The Role of Antiviral Therapy for HBV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:416459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Tarazov PG, Zhang Q S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN