Published online Mar 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.2906

Peer-review started: September 26, 2015

First decision: October 14, 2015

Revised: November 6, 2015

Accepted: December 30, 2015

Article in press: December 30, 2015

Published online: March 14, 2016

Processing time: 163 Days and 2.4 Hours

In the two past decades, a number of communications, case-control studies, and retrospective reports have appeared in the literature with concerns about the development of a complex set of clinical, laboratory and histological characteristics of a liver graft dysfunction that is compatible with autoimmune hepatitis. The de novo prefix was added to distinguish this entity from a pre-transplant primary autoimmune hepatitis, but the globally accepted criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis have been adopted in the diagnostic algorithm. Indeed, de novo autoimmune hepatitis is characterized by the typical liver necro-inflammation that is rich in plasma cells, the presence of interface hepatitis and the consequent laboratory findings of elevations in liver enzymes, increases in serum gamma globulin and the appearance of non-organ specific auto-antibodies. Still, the overall features of de novo autoimmune hepatitis appear not to be attributable to a univocal patho-physiological pathway because they can develop in the patients who have undergone liver transplantation due to different etiologies. Specifically, in subjects with hepatitis C virus recurrence, an interferon-containing antiviral treatment has been indicated as a potential inception of immune system derangement. Herein, we attempt to review the currently available knowledge about de novo liver autoimmunity and its clinical management.

Core tip: A post-transplant pathological entity that is characterized by liver enzyme peaks, circulating auto- and alloantibodies and histological findings of interface hepatitis and plasma-cell infiltrates has been described and is considered to be a diagnostic challenge. Although the optimization of the immunosuppressive regimen should be an efficacious tool for both its prevention and treatment, rescue onsets can occur with scenarios that threaten the graft and the patient’s life. Hepatitis C recurrence is not the only pathogenic context of its occurrence in liver transplants, thus the clinical interest in this condition remains high.

- Citation: Vukotic R, Vitale G, D’Errico-Grigioni A, Muratori L, Andreone P. De novo autoimmune hepatitis in liver transplant: State-of-the-art review. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(10): 2906-2914

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i10/2906.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.2906

Liver transplantation (LT) represents the rescue therapy for end-stage liver disease (ESLD). The management of LT recipients is a complex issue because the natural history of the long-term survivors has been observed to depend on the possible development of unpredictable clinical complications such as acute and chronic rejection, de novo autoimmunity, and fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis[1-3]. For nearly two decades, the literature has provided information about series of LT patients, including children and adults, who develop transaminases increases, histological features of plasma-cell infiltrate and typical autoimmune liver serology. This phenomenon has been observed to be particularly challenging when it occurs during treatment with interferon for hepatitis C virus (HCV) recurrence[4]. While the recurrence of genuine autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) after LT should be dreaded in the mid-long-term[5-8], true de novo AIH can develop unpredictably in any period following LT, particularly in the setting of HCV recurrence. The hypotheses regarding the pathogenic pathways are not conclusive, and the examined risk factors have primarily focused on immunosuppression reductions or withdrawals, predisposing graft and/or host haplotypes and the use of immunomodulating agents. A prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment of de novo AIH can prevent disease progression and graft loss.

Autoimmune-based liver graft injury typically characterized by features of AIH, but occurring in transplant recipients for ESLD not caused by a previous autoimmune liver disease, has been described over the years in pediatric and adult LT. Likely because of its incomplete understanding, this disease has not yet been given a universally accepted denomination. The most common name of this condition, i.e., de novo autoimmune hepatitis, was first used in 1998[9] (herein, “de novo” followed by the acronym AIH will be used), but has also been called post-LT AIH-like hepatitis[10], graft dysfunction mimicking AIH[11], posttransplant immune hepatitis[12], plasma-cell hepatitis[4,13], and de novo immune hepatitis[14]. The earliest descriptions of de novo AIH were reported in 1998 in pediatric patients and in 1999 in adult LT recipients who presented laboratory, autoimmune and histological features consistent with classic AIH[9,15]. A series of subsequent reports and studies increased the awareness of this disease in both children[12,16-30] and adults[4,11,13,14,31-53]. The experiences published thus far appear to be very heterogeneous in terms of methodology, patient identification and population size.

The earliest description of autoimmunity-related graft dysfunction in children[9] concerned 7/180 children who were observed for at least 5 years after LT. All seven of the patients presented histological features that were suggestive of de novo AIH: hypergammaglobulinemia, high titers of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and/or smooth muscle antibodies (SMA) and/or liver kidney microsomal (LKM) or even “atypical” LKM (only kidney stained) autoantibodies, and 6/7 exhibited satisfactory responses to steroids and azathioprine[9]. In this cohort, 5/7 patients had donor-HLA-DRB1*03:01 and/or HLA-DRB1*04:01 allele for human leukocyte antigen (HLA)[9], but the frequency was similar to the control group. Shortly after this description, a particularly severe course of de novo AIH in a pediatric population was described by Gupta et al[18] in 2001. These authors reported on 6/115 LT recipients with at least 5 years of post-LT observation who developed de novo AIH. The diagnosis was definitively confirmed by International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAHG)[54,55] score in only one child, and the results from the other children indicated probable de novo AIH[18]. Regardless, severe progression to bridging fibrosis occurred in 80% of the patients, and graft loss occurred in 33% despite steroid and azathioprine treatment[18]. In the past decades, the monitoring of graft dysfunction with possible autoimmune etiology was globally sensitized for adult LT recipients. Particular focus was put on patients with HCV recurrence who developed de novo AIH features during or following an interferon-based antiviral treatment course. At our hospital, 9/44 LT patients who were treated from 2001 to 2004 with pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) and ribarivin (RBV) for HCV recurrence experienced graft dysfunction compatible with de novo AIH[32]. Despite prompt treatment, 2/9 of these patients died, one had graft failure, and one required re-LT. Among the 5 patients for whom remission was obtained, 3 experienced HCV-RNA relapse. In this series, no association was observed between the HLA type and the development of de novo AIH. In contrast, the administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) for the treatment of neutropenia appeared to be a protective factor while the use of anti-lymphocyte antibodies was significantly correlated with the development of de novo AIH in this cohort[32]. Fiel et al[4] reported series of 214 biopsies from 38 LT recipients between 1994 and 2006 that met the criteria for plasma-cell hepatitis. A high rate (55%) of acute graft rejection was reported in this population. The patients received one of the following treatments either alone or in combination: azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, prednisone, methyl-prednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and increased doses of a calcineurin inhibitor. Satisfactory outcomes were observed in 40% of the patients, and among the remaining patients, 10 died, 3 underwent re-LT, and 10 developed disease progression to cirrhosis[4]. More recently, cases of plasma-cell hepatitis during or after triple antiviral therapy with Peg-IFN, RBV and telaprevir have been described. Ikegami et al[38] reported 3 cases of plasma-cell hepatitis development during Peg-IFN and RBV treatment, shortly after the completion of triple regimen with telaprevir. Because significant drug-drug interactions are known to occur between calcineurin inhibitors and telaprevir, the patients received reduced doses of cyclosporine during telaprevir co-administration and were closely monitored for cyclosporine levels[38]. Following the onset of plasma-cell hepatitis, all cases were rescued with immunosuppressive regimen optimization via steroid pulses, increased cyclosporine doses, and/or the addition of MMF. In one case, the antiviral treatment was stopped for safety issues[38].

Although the pathogenesis of de novo AIH in LT has not yet been fully clarified, it is generally accepted that this entity shares similar movens mechanisms with classical AIH. The susceptible genetic milieu given by HLA DRB1*0301 and/or DRB1*0401 alleles has been implicated in AIH pathogensis while its role in de novo AIH is inconclusive. It is thought that the presentation of antigens, either by the recipient or donor-presenting cells, triggers the memory T cells of the host’s immune system, which results in consequent self-directed immune reactions[8,56-58]. The auto-reactivity of the T cells is stimulated by a cause that is independent of chronic inflammatory noxa and possibly leads to the endogenous presentation of self-epitopes[59]. This phenomenon is known as “epitope spreading”[59-61]. The mechanisms that are thought to contribute to the genesis of liver graft autoimmunity are at least in part induced by immunosuppressive agents[8]. Calcineurin inhibitors may cause the impairment of T-reg cells function[8] via the recognition of self-antigens of the type II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) by the T cells in a manner similar to that observed in graft-vs-host disease, by inducing a reduction in the production of interleukin-2 which is normally required for the survival and the proliferation of T-reg cells[62]. Notably, interactions between immunosuppressors and the maturation of the T cells have been hypothesized to exert even greater influence on immature immunity e.g., in child LT recipients[63].

Moreover, viral molecular mimicry is believed to be among the potential causes of de novo autoimmunity[59], particularly the one exhibited by ubiquitous viruses, such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus, which are often found to infect immunosuppressed subjects and have been confirmed to be involved in a series of LT developing autoimmune features[49,64].

With special regard to the recurrence of HCV, the possible mechanisms that characterize de novo AIH in this setting have recently been delineated[2]. Specifically, it is hypothesized that interferon-alpha (acting on specific interferon-stimulated genes and in the context of the up-regulation of class I MHC) stimulates the activation of T-cells which, through the intensification of pro-inflammatory activity, enhance the presentation and release of antigens[2]. Apart from the virtuous effect on viral clearance, the recognition of viral antigens at the same time may lead to the expression of self-antigens, which can result in an alloimmune reaction sustained by memory T-cells[2,42,65].

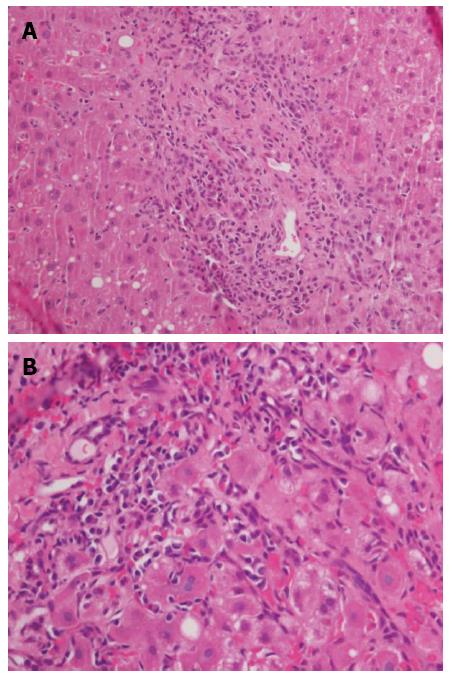

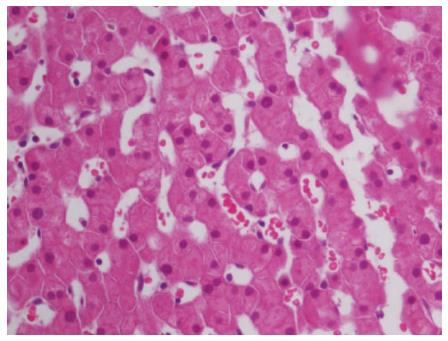

In complex clinical settings in which different parameters (e.g., the presence of autoantibodies without signs of effective liver injury) can mislead diagnosis, if a reasonable clinical suspicion emerges the liver biopsy should be performed. Thus far, the commonly observed histological characteristics of de novo AIH have been assimilated with those already described for classic AIH. Interface hepatitis and portal tract mononuclear infiltrate rich in plasma-cells are typical findings (Figure 1) along with accentuated lobular inflammation and necrosis, hepatocellular rosette (Figure 2) and features of centrolobular perivenulitis[1,66]. The interpretation of the liver histology is more complex for de novo AIH than for primary AIH because the former may be affected by conditions that resemble autoimmune liver injury and that by definition do not affect native livers, such as acute and chronic rejection[1]. A particularly abundant presence of plasma cells in the portal tract and an intense interface inflammation generally address the diagnosis but do not exempt from a careful differential appraisal[67,68]. Moreover, some intrinsic variables may influence the reading of liver allograft biopsy, such as the primary diagnosis that led to LT, the time from LT, the immunosuppressive regimen, the center’s previous experience in and awareness of the field, and the quality of information exchange between the clinician and pathologist[1,69].

The currently available data regarding the incidence of de novo AIH indicate rates of 5%-10% in pediatric LT recipients and 1%-2% in adult LT recipients, suggesting an infrequent post-LT complication in adults. Nonetheless, this disease should be considered when liver necrosis enzymes increase occurs in LT recipient, regardless of the post-LT epoch of development. Beginning with this laboratory finding, a differential algorithm is crucial for a correct diagnostic conclusion. Contextually, the elevation of gamma-globulin levels should be observed and graded, and the non-organ specific autoantibodies should be characterized[7,8] by an expert laboratory. In this sense, smooth-muscle antibodies positivity appears to be the most pathognomonic finding. With these concerns, the liver biopsy is performed and the histological features of de novo AIH should be observed to predominate over other etiologies of liver damage[66]. It is of note that in some cases, the diagnosis of de novo AIH arises from a standard one-year post-LT biopsy in the absence of prior major clinical or laboratory findings. Recently, an evaluation of the significance of non-organ specific autoantibodies was performed in a large transplanted population and revealed that the presence of serological autoimmunity seldom occurs in parallel with concrete clinical manifestations of autoimmune hepatitis[36]. This finding suggests, and it is indeed also our real-life experience, that liver biopsy is the most reliable diagnostic tool. The exclusion of possible distinct causes of graft dysfunction should comprise acute and chronic rejection, HCV recurrence focusing on its autoimmune-like presentation, biliary obstruction/stenosis, vascular complications, recurrent disease in recipients who received LT for primary biliary cirrhosis or primary sclerosing cholangitis and ex novo viral infections. Alternative biliary complications should be carefully excluded, particularly in patients who present with rapid laboratory deterioration including hyperbilirubinemia, which could reflect either a mechanical obstruction or the progression of underlying misrecognized de novo AIH to the deterioration of liver functionality. The application of the internationally agreed scoring systems for the diagnosis of AIH[54,70] to clinical, laboratory and histological parameters should definitely (or with high likelihood) confirm a suspected diagnosis of de novo AIH in subjects with consistent scores for whom the abovementioned alternative diseases can be excluded. However, in LT setting the immunosuppressive therapy could interfere with some of the parameters of the diagnostic criteria for the genuine AIH (e.g., autoantibody profile). A complete response to the standard immunosuppressive regimen for AIH (i.e., generous steroids doses in association with azathioprine) further supports the diagnosis. Notably, the steroids introduction for de novo AIH should be based on a meticulous diagnostic evaluation, particularly in patients with HCV recurrence, to prevent the exacerbation of viral replication[4].

The typical features that are common to each potential etiology of late graft dysfunction may be purposely reassumed to aid the differential diagnosis (Table 1). Nevertheless, despite apparently well-delineated diagnostic proceedings, a sharp distinction of de novo autoimmunity, particularly from forms of graft rejection, continues to be frequently question of nuance[4,34,65,66,71].

| de novo AIH | HCV recurrence | Acute rejection | Chronic rejection | |

| Laboratory onset | HBV/HCV/HIV/CMV/EBV negative | HCV-RNA positive | Transaminases elevation | Transaminases normal/slightly increased |

| Moderate liver enzymes increase | Low-moderate liver enzymes increase | Immunosuppressants levels under protective limits | Immunosuppressants levels under protective limits | |

| High IgG concentrations | ANA frequently positive | Autoantibodies negative or mild positive | Autoantibodies negative/mild positive | |

| Positivity for ANA, SMA, LKM, atypical LKM (anti-GSTT1), and/or AMA | SMA, AMA, LKM rarely positive | |||

| Clinical presentation | Onset variable from indolent to overt, may follow an antiviral treatment for HCV recurrence, especially when viral clearance is obtained | Gradual progression to cirrhosis except severe forms | Rapidly progressive deterioration of liver function scores | Silent onset |

| Slow progression to deterioration of liver function scores | ||||

| IAHG probable/definite diagnosis | ||||

| Histology | Portal tract infiltrate rich in plasma-cells | Chronic logistic infiltrate | Central perivenulitis | Biliary inflammatory and ischemic pattern: bile ductopenia and inflammation, artheriolar/capillary obliterative features or loss |

| Interface hepatitis | Possible interface hepatitis | Hepatic venous endothelitis | ||

| Rosette | Confluent/bridging necrosis | Mononuclear/mixed portal infiltrate | ||

| Lobular inflammation ± bridging/confluent necrotic foci | Progression to cirrhosis | |||

| Possible fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis | Bile ducts inflammation | |||

| Treatment | Prednis(ol)one ± MMF/azathioprine | Antiviral treatment | Steroids bolus | Steroids bolus |

| Immunosuppression levels monitoring | Adjustment of immunosuppressive regimen | Switch to/addition of a new immunosuppressant and/or optimization of current regimen) |

The current knowledge of de novo AIH suggests that whether and when a patient who has undergone LT for autoimmunity-unrelated liver disease will develop de novo AIH are not predictable. The relatively recent increase in the awareness of this clinical entity has effectively resulted in numerous reports in literature, but their heterogeneity continues to preclude the identification of clear predictive and risk factors of de novo AIH. Nevertheless, some studies have been conducted with this purpose. A large case-control study was conducted in the United States by Venick et al[17] with data from 788 grafts received by 619 children in a single center during an approximately twenty-year period. Among patients, 41 children who developed a de novo AIH (6.6%) were successively compared with control subjects who were matched in terms of the year of LT, age at LT and initial diagnosis[17]. None among the variables that were compared (age, gender, race, initial diagnosis, ischemia time, graft type, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections, HLA haplotype and immunosuppressive regimen) was found to be different between the two groups[17]. In contrast, the authors found that the number of patients in mono-immunosuppression, the number of patients to whom steroids were discontinued and the number of those who presented an allograft rejection were all higher in the group of de novo AIH[17]. Notably, in nearly all of the patients, prednisone with or without MMF was found to be a successful treatment choice[17].

In 2008[33], a study examined the potential role in the pathogenesis of de novo AIH of immunoglobulin subtype 4 (IgG4), which has been implicated in different autoimmune diseases[72]. Four of 72 (5.6%) adult living donor LT recipients who underwent transplantation within a 10-year period at a single center were diagnosed with de novo AIH[33]. The serum and liver tissue levels of IgG4 of these patients were adequately measured and found to be normal with the exception of one patient who exhibited only a mild positivity and thus suggesting that IgG4 is not a plausible co-factor in the development of de novo AIH[33].

Lodato et al[73] compared LT recipients treated with GCSF to those who did not receive GCSF in terms of the incidence of de novo AIH. A significantly lower incidence was observed in the GCSF group, which supports the protective immunomodulatory effect of GCSF against liver autoimmunity in the post-LT setting[73].

Several studies[14,74-76] were conducted that focused on the role of the glutathione S-transferase T1 (GSTT1) gene as a risk factor for de novo AIH development. Aguilera et al[77] identified in patients who present with de novo AIH, specific antibodies produced against donor GSTT1 gene due to a mismatch between the wild-type carried by the donor and recipient’s null genotype. Moreover, a retrospective analysis of liver biopsies from patients with de novo AIH who expressed GSTT1-Ab was conducted by the same authors to explore the presence of complement component 4d (C4d)[77]. C4d-positivity was observed to localize in the portal tracts of nearly all of the de novo AIH specimens, while in two control groups, sinusoidal C4d-positive pattern was present in 4/7 biopsies from patients who experienced rejection[77]. Finally, this question was further explored in successive studies that identified the influence of the type of immunosuppression on the definite clinical manifestations of GSTT1 genetic mismatch[78]. In the latter data, among 35 LT recipients a significantly greater proportion of those who did not produce anti-GSTT1 antibodies and did not manifest de novo AIH was observed among the patients who received tacrolimus (± MMF) than among those who received cyclosporine[78]. In a study of a GSTT1-mismatch positive LT population, the male gender of the donor and non-alcohol related pre-LT disease were found to be predictive of de novo AIH[79].

In another study[80] an enhanced immunosuppressive regimen that included steroids in addition to tacrolimus and MMF, has been shown to be protective against late graft rejection. In turn, as reported in the abovementioned studies, the occurrence of rejection was implied to be a predisposing factor for the appearance of de novo AIH[17]. Indeed, a study of a large series of adult LT recipients with features compatible with acute rejection observed that more than half of the patients were effectively diagnosed with de novo AIH[4].

Finally, it is worth noting that in LT recipients for HCV-related end-stage liver disease, HCV per se can be associated with serum autoimmunity profile positivity and the systemic manifestations of this condition[81,82]. Indeed, HCV infection is thought to incite autoimmune injury in genetically predisposed subjects[83].

Corticosteroids remain the milestone of the treatment of de novo AIH but should be accompanied by the optimization of calcineurin inhibitors posology[84]. Azathioprine or MMF should be added, whereas calcineurin inhibitors and steroids do not provide prompt benefit[84].

De novo autoimmunity in LT is a complex clinico-pathological issue due to both the incomplete understanding of its pathogenesis and its challenging diagnostic interpretation. Fortunately, growing experience and sensitivity to this post-LT complication have been elicited by numerous reports in the literature, in-depth pathophysiological studies and the sharing of real-life experiences of therapeutic approaches. Steroids seem to be successful in most cases, but there is no universally accepted therapeutic scheme, and the most adequate treatment needs to be tailored according to each patient’s clinical history and situation.

In the near future antiviral treatments for post-LT HCV recurrence will hopefully be fully based on potent new direct-acting antiviral agents in all-oral, interferon-free regimens. However, de novo AIH has been widely observed to develop in LT recipients with etiologies other than HCV. Therefore, given the complexity of the follow-up of liver allografts, strict awareness is needed in this setting for the detection and correct interpretation of liver enzymes increase, particularly during but not limited to long-term post-LT follow-up.

| 1. | Hübscher SG. What is the long-term outcome of the liver allograft? J Hepatol. 2011;55:702-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Selzner N, Guindi M, Renner EL, Berenguer M. Immune-mediated complications of the graft in interferon-treated hepatitis C positive liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2011;55:207-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Lucey MR, Terrault N, Ojo L, Hay JE, Neuberger J, Blumberg E, Teperman LW. Long-term management of the successful adult liver transplant: 2012 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:3-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fiel MI, Agarwal K, Stanca C, Elhajj N, Kontorinis N, Thung SN, Schiano TD. Posttransplant plasma cell hepatitis (de novo autoimmune hepatitis) is a variant of rejection and may lead to a negative outcome in patients with hepatitis C virus. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:861-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gautam M, Cheruvattath R, Balan V. Recurrence of autoimmune liver disease after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1813-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mendes F, Couto CA, Levy C. Recurrent and de novo autoimmune liver diseases. Clin Liver Dis. 2011;15:859-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Czaja AJ. Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2248-2266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liberal R, Longhi MS, Grant CR, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:346-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kerkar N, Hadzić N, Davies ET, Portmann B, Donaldson PT, Rela M, Heaton ND, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. De-novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Lancet. 1998;351:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khettry U, Huang WY, Simpson MA, Pomfret EA, Pomposelli JJ, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL, Gordon FD. Patterns of recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation in a recent cohort of patients. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:443-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heneghan MA, Portmann BC, Norris SM, Williams R, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton ND, O’Grady JG. Graft dysfunction mimicking autoimmune hepatitis following liver transplantation in adults. Hepatology. 2001;34:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Andries S, Casamayou L, Sempoux C, Burlet M, Reding R, Bernard Otte J, Buts JP, Sokal E. Posttransplant immune hepatitis in pediatric liver transplant recipients: incidence and maintenance therapy with azathioprine. Transplantation. 2001;72:267-272. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ward SC, Schiano TD, Thung SN, Fiel MI. Plasma cell hepatitis in hepatitis C virus patients post-liver transplantation: case-control study showing poor outcome and predictive features in the liver explant. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1826-1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aguilera I, Wichmann I, Sousa JM, Bernardos A, Franco E, García-Lozano JR, Núñez-Roldán A. Antibodies against glutathione S-transferase T1 (GSTT1) in patients with de novo immune hepatitis following liver transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:535-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jones DE, James OF, Portmann B, Burt AD, Williams R, Hudson M. Development of autoimmune hepatitis following liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kerkar N, Dugan C, Rumbo C, Morotti RA, Gondolesi G, Shneider BL, Emre S. Rapamycin successfully treats post-transplant autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1085-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Venick RS, McDiarmid SV, Farmer DG, Gornbein J, Martin MG, Vargas JH, Ament ME, Busuttil RW. Rejection and steroid dependence: unique risk factors in the development of pediatric posttransplant de novo autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:955-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gupta P, Hart J, Millis JM, Cronin D, Brady L. De novo hepatitis with autoimmune antibodies and atypical histology: a rare cause of late graft dysfunction after pediatric liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:664-668. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hernandez HM, Kovarik P, Whitington PF, Alonso EM. Autoimmune hepatitis as a late complication of liver transplantation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:131-136. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tamaro G, Sonzogni A, Torre G. Monitoring “de novo” autoimmune hepatitis (LKM positive) by serum type-IV collagen after liver transplant: a paediatric case. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;310:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gibelli NE, Tannuri U, Mello ES, Cançado ER, Santos MM, Ayoub AA, Maksoud-Filho JG, Velhote MC, Silva MM, Pinho-Apezzato ML. Successful treatment of de novo autoimmune hepatitis and cirrhosis after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Evans HM, Kelly DA, McKiernan PJ, Hübscher S. Progressive histological damage in liver allografts following pediatric liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2006;43:1109-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Herzog D, Soglio DB, Fournet JC, Martin S, Marleau D, Alvarez F. Interface hepatitis is associated with a high incidence of late graft fibrosis in a group of tightly monitored pediatric orthotopic liver transplantation patients. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:946-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Oya H, Sato Y, Yamamoto S, Kobayashi T, Watanabe T, Kokai H, Hatakeyama K. De novo autoimmune hepatitis after living donor liver transplantation in a 25-day-old newborn baby: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:433-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Spada M, Bertani A, Sonzogni A, Petz W, Riva S, Torre G, Melzi ML, Alberti D, Colledan M, Segalin A. A cause of late graft dysfunction after liver transplantation in children: de-novo autoimmune hepatitis. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1747-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Petz W, Sonzogni A, Bertani A, Spada M, Lucianetti A, Colledan M, Gridelli B. A cause of late graft dysfunction after pediatric liver transplantation: de novo autoimmune hepatitis. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1958-1959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Riva S, Sonzogni A, Bravi M, Bertani A, Alessio MG, Candusso M, Stroppa P, Melzi ML, Spada M, Gridelli B. Late graft dysfunction and autoantibodies after liver transplantation in children: preliminary results of an Italian experience. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cho JM, Kim KM, Oh SH, Lee YJ, Rhee KW, Yu E. De novo autoimmune hepatitis in Korean children after liver transplantation: a single institution’s experience. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2394-2396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hadžić N, Quaglia A, Cotoi C, Hussain MJ, Brown N, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Immunohistochemical phenotyping of the inflammatory infiltrate in de novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation in children. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:501-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wozniak LJ, Hickey MJ, Venick RS, Vargas JH, Farmer DG, Busuttil RW, McDiarmid SV, Reed EF. Donor-specific HLA Antibodies Are Associated With Late Allograft Dysfunction After Pediatric Liver Transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99:1416-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Keaveny AP, Gordon FD, Khettry U. Post-liver transplantation de novo hepatitis with overlap features. Pathol Int. 2005;55:660-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Berardi S, Lodato F, Gramenzi A, D’Errico A, Lenzi M, Bontadini A, Morelli MC, Tamè MR, Piscaglia F, Biselli M. High incidence of allograft dysfunction in liver transplanted patients treated with pegylated-interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin for hepatitis C recurrence: possible de novo autoimmune hepatitis? Gut. 2007;56:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Eguchi S, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, Tajima Y, Zen Y, Nakanuma Y, Kanematsu T. De novo autoimmune hepatitis after living donor liver transplantation is unlikely to be related to immunoglobulin subtype 4-related immune disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e165-e169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Merli M, Gentili F, Giusto M, Attili AF, Corradini SG, Mennini G, Rossi M, Corsi A, Bianco P. Immune-mediated liver dysfunction after antiviral treatment in liver transplanted patients with hepatitis C: allo or autoimmune de novo hepatitis? Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhao XY, Rakhda MI, Wang TI, Jia JD. Immunoglobulin G4-associated de novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B- and C-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report with literature review. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:824-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Foschi A, Zavaglia CA, Fanti D, Mazzarelli C, Perricone G, Vangeli M, Viganò R, Belli LS. Autoimmunity after liver transplantation: a frequent event but a rare clinical problem. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Castillo-Rama M, Sebagh M, Sasatomi E, Randhawa P, Isse K, Salgarkar AD, Ruppert K, Humar A, Demetris AJ. “Plasma cell hepatitis” in liver allografts: identification and characterization of an IgG4-rich cohort. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2966-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Shirabe K, Maehara Y. Frequent plasma cell hepatitis during telaprevir-based triple therapy for hepatitis C after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2014;60:894-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rodríguez-Diaz Y, Reyes-Rodriguez R, Dorta-Francisco MC, Aguilera I, Perera-Molinero A, Moneva-Arce E, Aviles-Ruiz JF. De novo autoimmune hepatitis following liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:1467-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cholongitas E, Samonakis D, Patch D, Senzolo M, Burroughs AK, Quaglia A, Dhillon A. Induction of autoimmune hepatitis by pegylated interferon in a liver transplant patient with recurrent hepatitis C virus. Transplantation. 2006;81:488-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kontorinis N, Agarwal K, Elhajj N, Fiel MI, Schiano TD. Pegylated interferon-induced immune-mediated hepatitis post-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:827-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Takeishi K, Shirabe K, Toshima T, Ikegami T, Morita K, Fukuhara T, Motomura T, Mano Y, Uchiyama H, Soejima Y. De novo autoimmune hepatitis subsequent to switching from type 2b to type 2a alpha-pegylated interferon treatment for recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011;41:1016-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Levitsky J, Fiel MI, Norvell JP, Wang E, Watt KD, Curry MP, Tewani S, McCashland TM, Hoteit MA, Shaked A. Risk for immune-mediated graft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients with recurrent HCV infection treated with pegylated interferon. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1132-1139.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Salcedo M, Vaquero J, Bañares R, Rodríguez-Mahou M, Alvarez E, Vicario JL, Hernández-Albújar A, Tíscar JL, Rincón D, Alonso S. Response to steroids in de novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2002;35:349-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tan CK, Sian Ho JM. Concurrent de novo autoimmune hepatitis and recurrence of primary biliary cirrhosis post-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:461-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Yoshizawa K, Shirakawa H, Ichijo T, Umemura T, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Imagawa E, Matsuda K, Hidaka E, Sano K. De novo autoimmune hepatitis following living-donor liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:385-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Inui A, Sogo T, Komatsu H, Miyakawa H, Fujisawa T. Antibodies against cytokeratin 8/18 in a patient with de novo autoimmune hepatitis after living-donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:504-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zhang Y, Wang B, Wang T. De novo autoimmune hepatitis with centrilobular necrosis following liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3854-3857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Sakamoto T, Sato Y, Yamamoto S, Oya H, Hatakeyama K. De novo ulcerative colitis and autoimmune hepatitis after living related liver transplantation from cytomegalovirus-positive donor to cytomegalovirus-negative recipient: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:570-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Haga H, Egawa H, Hayashino Y, Sakurai T, Minamiguchi S, Tanaka K, Manabe T. Outcome and risk factors of de novo autoimmune hepatitis in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:128-135. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Haga H, Sakurai T, Shirase T, Manabe T, Egawa H. De novo autoimmune hepatitis affecting allograft but not the native liver in auxiliary partial orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76:271-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Casanovas T, Argudo A, Peña-Cala MC. Effectiveness and safety of everolimus in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis related to anti-hepatitis C virus therapy after liver transplant: three case reports. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2233-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sebagh M, Castillo-Rama M, Azoulay D, Coilly A, Delvart V, Allard MA, Dos Santos A, Johanet C, Roque-Afonso AM, Saliba F. Histologic findings predictive of a diagnosis of de novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation in adults. Transplantation. 2013;96:670-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 2017] [Article Influence: 74.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG. Meeting report: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology. 1993;18:998-1005. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Guido M, Burra P. De novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:71-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sanchez-Fueyo A. Tolerance profiles and immunosuppression. Liver Transpl. 2013;19 Suppl 2:S44-S48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. De novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2004;40:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Getts DR, Chastain EM, Terry RL, Miller SD. Virus infection, antiviral immunity, and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2013;255:197-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Vanderlugt CJ, Miller SD. Epitope spreading. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:831-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Vanderlugt CL, Miller SD. Epitope spreading in immune-mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:85-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 62. | Kang HG, Zhang D, Degauque N, Mariat C, Alexopoulos S, Zheng XX. Effects of cyclosporine on transplant tolerance: the role of IL-2. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1907-1916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Schreuder TC, Hübscher SG, Neuberger J. Autoimmune liver diseases and recurrence after orthotopic liver transplantation: what have we learned so far? Transpl Int. 2009;22:144-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Varani S, Muratori L, De Ruvo N, Vivarelli M, Lazzarotto T, Gabrielli L, Bianchi FB, Bellusci R, Landini MP. Autoantibody appearance in cytomegalovirus-infected liver transplant recipients: correlation with antigenemia. J Med Virol. 2002;66:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Fiel MI, Schiano TD. Plasma cell hepatitis (de-novo autoimmune hepatitis) developing post liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:287-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Demetris AJ, Adeyi O, Bellamy CO, Clouston A, Charlotte F, Czaja A, Daskal I, El-Monayeri MS, Fontes P, Fung J. Liver biopsy interpretation for causes of late liver allograft dysfunction. Hepatology. 2006;44:489-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Kallwitz ER. Recurrent hepatitis C virus after transplant and the importance of plasma cells on biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:158-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Carbone M, Neuberger JM. Autoimmune liver disease, autoimmunity and liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2014;60:210-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 69. | Pappo O, Ramos H, Starzl TE, Fung JJ, Demetris AJ. Structural integrity and identification of causes of liver allograft dysfunction occurring more than 5 years after transplantation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:192-206. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, Cançado EL, Mackay IR, Manns MP, Nishioka M, Penner E. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41:677-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Vasuri F, Malvi D, Gruppioni E, Grigioni WF, D’Errico-Grigioni A. Histopathological evaluation of recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2810-2824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Zen Y, Fujii T, Harada K, Kawano M, Yamada K, Takahira M, Nakanuma Y. Th2 and regulatory immune reactions are increased in immunoglobin G4-related sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1538-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Lodato F, Azzaroli F, Tamè MR, Di Girolamo M, Buonfiglioli F, Mazzella N, Cecinato P, Roda E, Mazzella G. G-CSF in Peg-IFN induced neutropenia in liver transplanted patients with HCV recurrence. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5449-5454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Aguilera I, Wichmann I, Sousa JM, Bernardos A, Franco E, Garcia-Lozano R, Gonzalez-Escribano MF, Núñez-Roldán A. Antibodies against glutathione S-transferase T1 in patients with immune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Aguilera I, Sousa JM, Gavilán F, Bernardos A, Wichmann I, Nuñez-Roldán A. Glutathione S-transferase T1 mismatch constitutes a risk factor for de novo immune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1166-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Aguilera I, Sousa JM, Gavilan F, Bernardos A, Wichmann I, Nuñez-Roldan A. Glutathione S-transferase T1 genetic mismatch is a risk factor for de novo immune hepatitis in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3968-3969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Aguilera I, Sousa JM, Gavilan F, Gomez L, Alvarez-Márquez A, Núñez-Roldán A. Complement component 4d immunostaining in liver allografts of patients with de novo immune hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:779-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Aguilera I, Sousa JM, Praena JM, Gómez-Bravo MA, Núñez-Roldan A. Choice of calcineurin inhibitor may influence the development of de novo immune hepatitis associated with anti-GSTT1 antibodies after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:207-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Salcedo M, Rodríguez-Mahou M, Rodríguez-Sainz C, Rincón D, Alvarez E, Vicario JL, Catalina MV, Matilla A, Ripoll C, Clemente G. Risk factors for developing de novo autoimmune hepatitis associated with anti-glutathione S-transferase T1 antibodies after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:530-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Wiesner RH, Steffen BJ, David KM, Chu AH, Gordon RD, Lake JR. Mycophenolate mofetil use is associated with decreased risk of late acute rejection in adult liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1609-1616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | McCaughan GW, Zekry A. Effects of immunosuppression and organ transplantation on the natural history and immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Transpl Infect Dis. 2000;2:166-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Zignego AL, Giannini C, Gragnani L, Piluso A, Fognani E. Hepatitis C virus infection in the immunocompromised host: a complex scenario with variable clinical impact. J Transl Med. 2012;10:158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Zignego AL, Wojcik GL, Cacoub P, Visentini M, Casato M, Mangia A, Latanich R, Charles ED, Gragnani L, Terrier B. Genome-wide association study of hepatitis C virus- and cryoglobulin-related vasculitis. Genes Immun. 2014;15:500-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193-2213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1039] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 64.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Aguilera I S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S