Published online Dec 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12896

Peer-review started: April 19, 2015

First decision: July 14, 2015

Revised: August 5, 2015

Accepted: October 13, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: December 7, 2015

Processing time: 232 Days and 15.9 Hours

AIM: To summarize the current knowledge about the potential relationship between hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and the risk of several extra-liver cancers.

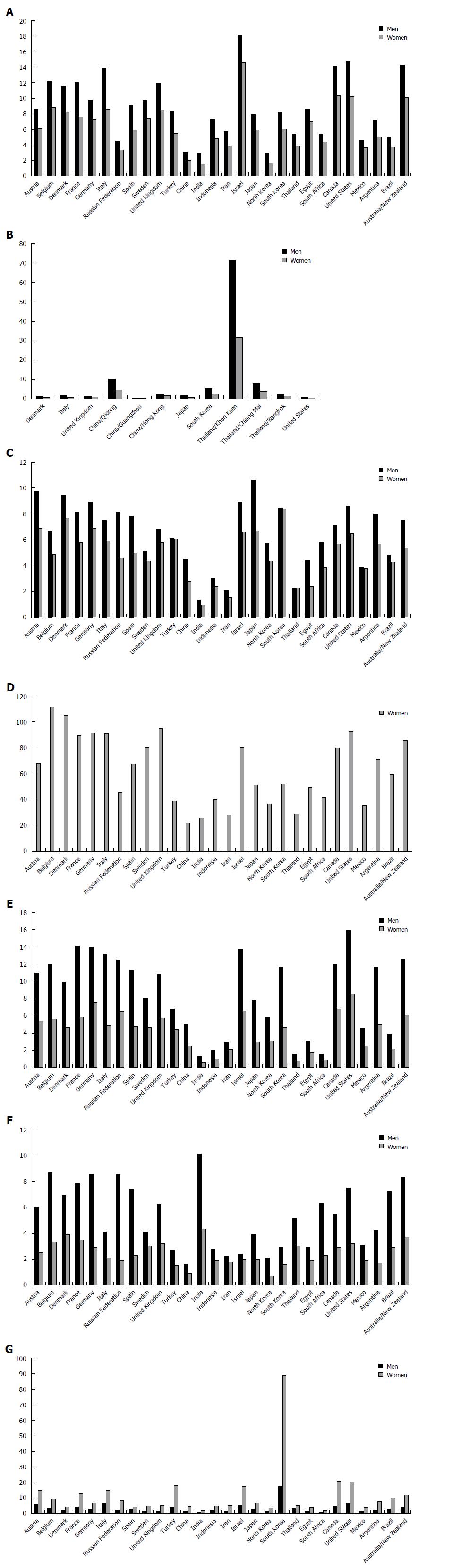

METHODS: We performed a systematic review of the literature, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement. We extracted the pertinent articles, published in MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library, using the following search terms: neoplasm/cancer/malignancy/tumor/carcinoma/adeno-carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, kidney/renal-, cholangio-, pancreatic-, thyroid-, breast-,oral-, skin-, prostate-, lung-, colon-, stomach-, haematologic. Case series, case-series with control-group, case-control, cohort-studies as well as meta-analyses, written in English were collected. Some of the main characteristics of retrieved trials, which were designed to investigate the prevalence of HCV infection in each type of the above-mentioned human malignancies were summarised. A main table was defined and included a short description in the text for each of these tumours, whether at least five studies about a specific neoplasm, meeting inclusion criteria, were available in literature. According to these criteria, we created the following sections and the corresponding tables and we indicated the number of included or excluded articles, as well as of meta-analyses and reviews: (1) HCV and haematopoietic malignancies; (2) HCV and cholangiocarcinoma; (3) HCV and pancreatic cancer; (4) HCV and breast cancer; (5) HCV and kidney cancer; (6) HCV and skin or oral cancer; and (7) HCV and thyroid cancer.

RESULTS: According to available data, a clear correlation between regions of HCV prevalence and risk of extra-liver cancers has emerged only for a very small group of types and histological subtypes of malignancies. In particular, HCV infection has been associated with: (1) a higher incidence of some B-cell Non-Hodgkin-Lymphoma types, in countries, where an elevated prevalence of this pathogen is detectable, accounting to a percentage of about 10%; (2) an increased risk of intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma; and (3) a correlation between HCV prevalence and pancreatic cancer (PAC) incidence.

CONCLUSION: To date no definitive conclusions may be obtained from the analysis of relationship between HCV and extra-hepatic cancers. Further studies, recruiting an adequate number of patients are required to confirm or deny this association.

Core tip: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an oncogenic virus and a well-known risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Some reports suggested that its infection is associated with development of cholangiocarcinoma and some types of lymphomas, but a comprehensive assessment of the possible role of HCV in extrahepatic carcinogenesis has not been yet performed. Aim of this review is to focus on HCV infection association with extra-liver neoplasms, as lymphomas, pancreatic cancer and breast-, renal-, oral- and thyroid-cancers. Our results strongly support the need of additional studies to ensure a precise estimate of the effect of HCV on these different types of extra-hepatic cancers.

- Citation: Fiorino S, Bacchi-Reggiani L, de Biase D, Fornelli A, Masetti M, Tura A, Grizzi F, Zanello M, Mastrangelo L, Lombardi R, Acquaviva G, di Tommaso L, Bondi A, Visani M, Sabbatani S, Pontoriero L, Fabbri C, Cuppini A, Pession A, Jovine E. Possible association between hepatitis C virus and malignancies different from hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(45): 12896-12953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i45/12896.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12896

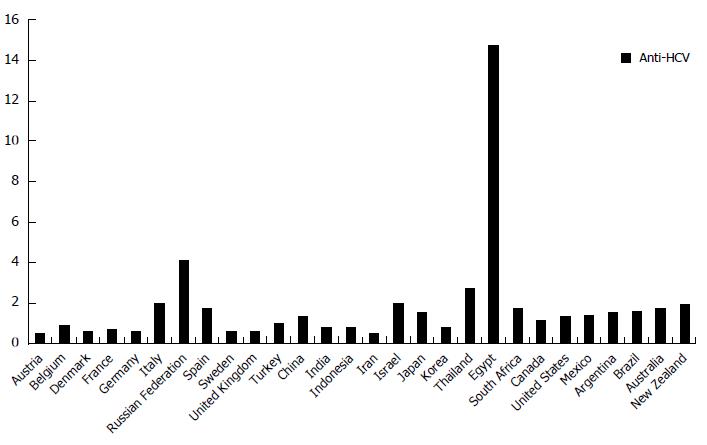

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major global health problem, because it represents a very important cause of mortality, morbidity and resource utilization. Although remarkable differences are detectable in the world, depending on geographical areas and ethnicity, it is estimated that the prevalence of HCV infection is about 2% worldwide (Figure 1)[1]. Approximately 180 million people carriers this pathogen persistently[2]. HCV chronic infection can lead to a necro-inflammatory liver disease, with different pattern of severity and course. This condition is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma[3]. Although liver is the main target for HCV, it is now well-known that this pathogen may induce extra-hepatic pathological conditions, including mixed cryoglobulinemia, porphyria cutanea tarda, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, thyroiditis, a high prevalence of autoantibodies[4] as well as Central and Peripheral Nervous System demyelinating disorders[5]. Several of these manifestations are thought to be caused by the host immune response to this micro-organism and not by a direct viral cytopathic effect. In particular, chronic antigenic stimulation by HCV promotes B-lymphocyte clonal expansion, with the production and release of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies and generation of immune complexes[6]. Their deposition in small vessels and glomerular capillary walls induces complement activation and, as consequence, tissue injury[7]. In addition, several studies have shown that HCV may infect organs and tissues other than the liver. In particular, presence of antigens, genome and/or replicative sequences of HCV have been detected in several extra-hepatic localizations, such as peripheral blood cells (i.e., neutrophils, T- and B-lymphocytes)[8,9] or kidney[10], skin[11,12], oral mucosa[13], salivary glands[14] and pancreas tissues as well as, in a small number of cases, from heart, gallbladder, intestine and adrenal glands tissues[15,16].

Although HCV antigens and replicative forms have been detected in various extra-hepatic sites, the possible role on the onset of malignancies in these organs is still under investigation. Some evidences have recently suggested the possibility that this pathogen may be associated with the development of a wide spectrum of hematologic or solid cancers, such as non-Hodgkin lymphomas, biliary duct-, bladder-, renal-, pancreatic-, thyroid-, breast- and prostate-carcinomas. Here we summarize the current knowledge about the potential link between HCV infection and risk of these malignancies and we performed a systematic review of the literature that reports the prevalence of HCV infection in patients, suffering from above mentioned malignancies.

See supplementary Material and Methods for further information.

A systematic computer-based search of published articles, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement, issued in 2009, was conducted through Ovid interface, in order to identify relevant studies on the potential association between HCV infection and malignancies other than hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The literature review was performed in February 2015. The following electronic databases were used: MEDLINE (1950 to February, 2015) and the Cochrane Library (until the fourth quarter of 2014) for all relevant articles. The search strategy and the search terms were developed with the support of a professional research librarian. The search text words were identified by means of controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MESH (Medical Subject Headings) and Keywords. In our review, assessing the possible association between HCV infection and risk of malignancies other than HCC, we focused on the following malignancies: (1) lymphomas and, in particular, non-Hodgkin lymphomas; (2) biliary ducts-/gallbladder-; (3) renal-/kidney-; (4) pancreatic-; (5) thyroid-; (6) breast-; (7) lung-; (8) stomach-; (9) colon-; (10) skin-/oral-; (11) bladder-; and (12) prostate-carcinomas. The inclusion criteria for our analysis were: (1) study designs by considering data from all published case series, case-control-, hospital-based case-control-, population-based case-control- as well as cohort-studies; (2) articles which were reported in English, as peer-reviewed, full-text publications, whereas papers that were not published as full reports, such as conference abstracts, case reports, and editorials were excluded; (3) clinical series or studies evaluating histological specimens, that included at least 15 patients, therefore reports with fewer than 15 subjects were not considered; and (4) papers describing the type of tests used to assess HCV presence; in particular, in all studies virus search was performed by means of second- or third-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA) for confirmation as well as in a large part of available trials HCV-RNA presence was also tested.

Data extraction: Two authors (Masetti M and Bacchi-Reggiani L), independently and in a parallel manner, performed the literature search, identified and screened relevant articles, based on title or title and abstract. If a study was considered potentially eligible by either of the 2 reviewers, the full article of this research was collected for further assessment. Other two authors (Zanello M and Mastrangelo L) independently extracted and tabulated all relevant data from included studies by means of a standardized flow path, according to the Cochrane handbook section 7.3a checklist of domains. The following information was obtained from each study, by means of a predefined data extraction form, including: first author’s name, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, matching criteria, number of cases and controls, diagnostic methods to detect each malignancy, HCV detection assays. The accuracy of data collection was checked by Tura A and any disagreements concerning the results were settled by consensus between all authors. With the purpose to prevent multiple inclusions of the same data, we searched the presence of possible duplicates, examining the first author’s name as well as the place and the period of subjects’ enrolment. When different versions of the same study were detected, only the most recent one was considered.

The search of MEDLINE and Cochrane Library produced the following citations: (1) haematopoietic malignancies: 1424; (2) biliary ducts-/cholangio-: 616; (3) renal-/kidney-: 891; (4) pancreatic-: 244; (5) thyroid-: 126; (6) breast-: 180; (7) lung-: 247; (8) stomach-: 141; (9) colon-: 115; (10) skin-/oral-: 598; (11) bladder-: 150; and (12) prostate-carcinomas: 43.

After a preliminary review of the titles and/or abstracts with the exclusion of non-pertinent articles, we obtained these results: (1) haematopoietic malignancies, including lymphomas/non-Hodgkin lymphomas: 126; (2) biliary ducts-/cholangio-: 48; (3) renal-/kidney-: 10; (4) pancreatic-: 15; (5) thyroid-: 11; (6) breast-: 8; (7) lung-: 3; (8) stomach-: 2; (9) colon-: 5; (10) skin-/oral-: 11; (11) bladder-: 3; and (12) prostate-carcinomas: 5.

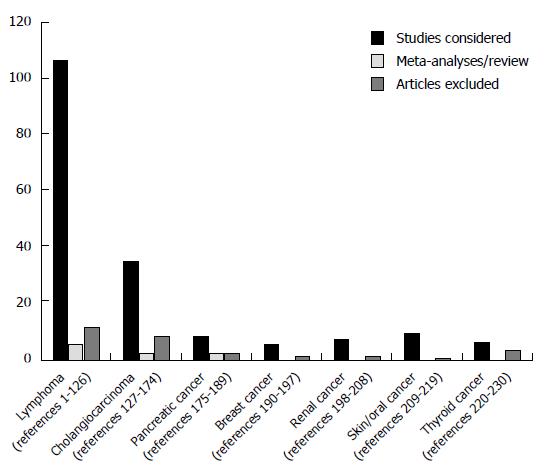

We screened the potentially relevant studies and, in accordance with predefined criteria, we identified and considered in our systematic review the following number of studies: (1) haematopoietic malignancies: 108 articles considered, 6 reviews/meta-analyses, 12 papers excluded[17-146]; (2) biliary ducts/cholangiocarcinoma: 36 articles considered, 3 reviews/meta-analyses, 9 papers excluded[147-195]; (3) renal/kidney: 8 articles considered, 2 papers excluded[118,146,196-203]; (4) pancreatic: 9 articles considered, 3 reviews/meta-analyses, 3 papers excluded[118,146,170,197,204-214]; (5) thyroid: 7 articles considered, 4 papers excluded[52,73,118,146,196,197,215-217]; (6) breast: 6 articles considered, 2 papers excluded[117,118,146,196,197,202,218,219]; (7) lung: 2 articles meeting inclusion criteria, 1 not[146,196,197]; (8) stomach: 2 articles meeting inclusion criteria[146,220]; (9) colon: 3 articles meeting inclusion criteria, 2 not[118,146,196,197,202]; (10) skin/oral: 10 articles considered, 1 paper excluded[118,146,197,221-228]; (11) bladder: 3 articles meeting inclusion criteria[118,146,197]; and (12) prostate-carcinomas: 4 articles meeting inclusion criteria, 1 not[118,146,196,197,202] (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7). A limited number of identified studies were formally designed as “cohort-“ or “case-control” trials, adequately reporting inclusion criteria for the control group, such as “odds ratios” after adjustment for the most important confounding factors, or showing that cases and controls were matched by sex and age. Whether these data were not indicated, but an acceptable series of healthy subjects or patients with different diseases were recruited for comparison and were described, we defined the considered study, as: “case series with control group”.

| Author/Journal/Publication year | Study design | Diagnosis | HCV positive HM/total HM | Control source | HCV positive controls/total controls | Percentage of HCV-positive cases with 95%CI | Main conclusions |

| Akdogan M Turk J Gastroenterol 1998 | Case series study with control group Period: NR | All lymphomas: NHLs: 30 HL: 18 NHLs NHL classification: Working Formulation | (1) NHL: 4/30 (13.3%) (2) Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma | (2) Healthy blood donors | (1) 17/9488 (0.8%) | 13.3 (3.8-30.7) | Increased prevalence of HCV persistent infection in patients with NHL, but not in patients with HL, in comparison with general population |

| Amin J J Hepatol 2006 | Community-based cohort-study Period: 1990-2002 | NHLs Cohort of HCV positive patients: 75834, Cohort of HBV/HCV positive patients: 2604 Incidence of LNHs observed in the study cohort was compared to expected incidence derived from New South Wales population cancer rates by calculating standardised incidence ratios | Individuals with HCV infection: 75834 LNH cases detected: 33 | Incidence observed in the study cohort was compared to expected incidence derived from NSW population cancer rates by calculating standardised incidence ratios (SIR) | SIR: 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 0.04 (0.03-0.05) | In HCV infection group no increased overall risk of NHL-cell lymphoma, but, a number of B-cell NHLs (diffuse NHL, immunoproliferative malignancies and chronic lymphocytic leukaemias) had SIRs greater than one |

| Anderson LA Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008 | Population-based nested case-control study of hematopoietic malignancies Period: 1993 and 2002 | Subjects with hematopoietic malignancies identified, using SEER-Medicare data. SEER program: a cancer surveillance program supported by the National Cancer Institute and covering about 25% of United States population NHL classification: World Health Organization classification Myeloproliferative malignancies classification: acute- and chronic myeloid leukaemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myeloproliferative disease | 195/61464 (0.3%) cases with Hemato-poietic malignancies identified NHLs: 103/33940 (0.3%) DLBCL: 34/10144 (0.3%) BL: 2/197 (1.5%) MZL: 12/1908 (0.6%) FL: 19/4491 (0.4%) CLL: 23/10170 (0.2%) LL: 2/1148 HL: 3/1155 (0.3%) PCM: 31/9995 (0.3%) Myeloid neoplasm: 47/11945 (0.4%) AML: 23/6068 (0.4%) CML: 1/1528 (0.1%) MS: 18/3084 (0.6%) CMD: 1/1346 (0.1%) | Controls were identified by means of Medicare, a federally funded program administered by the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services, For each included case, two controls were selected at random from the 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries | 264/122531 (0.2%) population-based controls identified | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | Association between HCV and elevated risk of NHLs and acute myeloid leukemia. HCV may induce lymphoproliferative malignancies through chronic immune stimulation |

| Arcaini L Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia 2011 | Case series study with control group Period: NR | Splenic MZLs NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | 25/92 Splenic MZL patients (27.2%) | Patients (122) with WMc 66/122 subjects with HCV markers | 6/66 WMc patients (9%) | 27.2 (18.1-36.2) | Despite similar outcomes among SMZL and WM, SMZL appears as a disease with distinct clinical and histologic characteristics, and a peculiar association with HCV infection |

| Arican A Med Oncol 2000 | Case series Period: February-October 1997 | NHLs Low-grade: 12 (27%) Intermediate grade: 24 (55%) High-grade: 8 (18%) NHL classification: Working Formulation | 2/44 (4.5%) | NR | NR | 4.5 (0-10.7) | No association between HCV chronic infection and NHL development in this study. The prevalence of HCV infection reported to be 0.3%-1.5% in healthy Turkish-blood donors in previous studies be 1.5% in healthy Turkish-blood donors in previous |

| Aviles A Med Oncol 2003 | Case-control study Period: January 1997-December 1999 | B-cell NHLs: 416 Diffuse large cell: 236 Follicular: 97 Marginal B-cell zone: 83 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | B-cell NHLs 2/416 (0.5%) | Group 1: 682 first-degree relatives (spouses, children, fathers, and brothers of the patient) living in the neighboring area of the patient. Group 2: 832 healthy blood donors, donating during the same period of time at the central blood bank. Group 3: Neoplastic disease group, with 408 patients with solid tumors, breast cancer:127 colon cancer: 94 gastric cancer; 79 lung cancer: 98 Group 4: 353 patients with HCV-positive related chronic liver disease | Prevalence of HCV equal to: (1) 0 among first-degree relatives of patients (2) 0.12 (0.02-0.88) among healthy blood donors (3) 0.56, (0.28-0.75). among patients with solid tumors (4) No patients with HCV chronic liver disease developed malignant lymphoma in a median follow-up of 7.9 yr | 0.5 (0-1.1) | Association between HCV infection and development of malignant lymphoma represents an hazardous observation, the close association reported in areas with a higher prevalence of HCV infection has to be considered with caution, because other epidemiological factors have not been considered, such as a high prevalence of HCV infection compared to other areas |

| Bauduer F Hematol Cell Ther 1999 | Case series Period: January 1995-June 1998 | NHLs: 136 subjects B-cell-NHLs: 110 patients NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) histological scheme | 2/136 (1.5%) | NR | NR | 1.5 (0-3.4) | No evidence of relationship between HCV and NHLs |

| Besson C J Clin Oncol 2006 | Case control Period: March 1993-June 2002 | B-NHL (DLBCL) NHL classification: Working Formulation | 26/5586 (0.5%) | (1) HCV negative patients with DLCL enrolled in the present study (2) individuals with DLCL randomly chosen among HCV-negative patients included in the GELA program | (1) 5586 (2) 35 | 0.5 (0.29-0.64) | HCV-positive patients with DLBCL differ from other patients both at presentation and during chemotherapy. Specific protocols evaluating antiviral therapy should be designed for these patients |

| Bianco E Haematologica 2004 | Italian multi-center case-control study Period: January 1998 -February 2001 | All lymphomas: 637 HD: 157 CLL: 100 ALL: 54 MM: 107 AML: 140 CML: 49 T-NHL: 30 NHL classification for T-NHLs: REAL/WHO classification | 44/637 (6.9%) HD: 5/157 (3.2%) CLL: 9/100 (9%) ALL: 4/54 (7.6%) MM: 5/107 (4.7%) AML: 11/140 (7.9%) CML: 6/49 (12.2%) T-NHL 4/30 (13.8%) | Patients from other departments of the same hospitals: the departments of dentistry, dermatology, general surgery, gynecology, internal medicine, ophthalmology, orthopedics, otorhinolaryngology, and traumatology | 22/396 (5.6%) | 6.9 (4.9-8.8) | Possible association of HCV infection not only with B-NHL but also with some other lymphoid and myeloid malignancies, however no definitive significant results, due to the absence of large groups of patients to confirm this assumption |

| Bronowicki JP Hepatology 2003 | Case records Data obtained from the hepatology gastroenterology, hematology, internal medicine and pathology departments of 64 French hospitals Period: 1992-1999 | All PLL: 31 cases, 27/31 patients with a B-cell lymphoma: -DLBCL: 22, -BL: 1, -EMZBL of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: 3, unclassified, small B-cell lymphoma:1, T-cell lymphomas: 4 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | HCV-test available for 28 subjects, HCV test available in 23 patients with B-cell PLL 1 HCV positive patient with peripheral T-cell lymphoma 5/23 (21.7%) | NR | NR | 21.7 (7.5- 43.7) | This study confirms the rarity of PLL and demonstrates an increased prevalence of HCV infection |

| Cavanna L Haematologica 1995 | Case- control study Period: 1985-1990 | All LPDs: 300 patients Anti-HCV positive patients 57/300 (19.7%) NHLs: 150; HL: 20 CLL: 40 Plasma cell discrasias: 90 | NHL: 38/150 (25.3%) HL: 2/20 (10%) CLL: 2/40 (5%) Plasma cell discrasias: 15/90(16%) | Blood donors | 53/3108 (1.7%) | 25.3 (18.3-32.3) | High prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies among patients with lymphoprolipherative disorders as compared with the control group of healthy blood donors |

| Caviglia GP J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014 | Cohort study Period: January 2006 -December 2013 | 1313 patients with chronic HCV hepatitis 121 patients with extra-hepatic manifestations: B-NHL: 41/1323 (3.1%) MCS: 25/1323 (1.9%) MGUS: 55/1323 (4.2%) NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | B-cell NHL: 41 MZL: 15 (36.6%), had DLBCL: 10 (24.4%), FL: 4 (9.8%) LPL; 1 (2.4%), MM: 1 (2.4%), CLL: 1 (2.4%) and B-NHL not otherwise specified: 9 (22%) | Controls selected on the basis of the absence of extra-hepatic manifestation of HCV infection | 130 HCV positive subjects without extrahepatic manifestation | 3.1 (2.2-4) | Cirrhosis is an additional risk factor for the development of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with chronic HCV infection |

| Chindamo MC Oncol Rep 2002 | Case series with control group Period: May 1995 -September 1998 | All lymphomas: 207 -HL: 67 -B-NHL: 87 -T-NHL: 22 -CLL: 31 NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) histological scheme | B-cell NHL: 8/87 (9.2%) | (1) Blood donors (2) Other haematological malignancies (Hodgkin’s disease and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia) | (1) 472/39371 (1.2%) (2) 2/98 (2%) | 9.2 (3.1-15.2) | Association between HCV infection and NHLs |

| Chuang SS J Clin Pathol 2010 | Case-control study Period: January 2004 -December 2008 | All malignancies: 346 -HL: 25 (3HCV+) -B-NHL: 321 (DLBCL, FC CLL, MZL, BL, others) -T- or NK/T-cell NHL: 55 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | All NHL: 35/321 (11%) B-cell NHL: 34/266 (12.8%) (3/38 with HBV coinfection) | Healthy Taiwanese subjects | 15/824 (1.8%) | 12.8 (8.7-16.8) | The incidence of HCV infection among lymphoma patients in Taiwan was significantly higher than that for healthy controls Non-MALT (nodal and splenic) MZL was the only group significantly associated with HCV |

| Cocco P Int J Hematol 2008 | Case-control study Period: -February 1999 - October 2002 - January 2002 - July 2003 | All malignancies (277): -HL: 13 -NHL: 264 (DLBCL, FC CLL, MZL, MM, T-cell NHL, others) NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | (1) All B cell- NHL: 20/237 (8.4%) (2) NHLs (excluding CLL and MM): 15/177 (8.5%) | Randomly selected controls from population registrars | 9/217 (4.1%) | (1) 8.4 (4.9-11.9) (2) 8.5 (4.3-12.5) | Acute or chronic hepatitis C is associated with a consistent risk increase in all lymphoma subtypes, but follicular lymphoma |

| Collier JD Hepatology 1999 | Case series with control group Period: February 1997 and May 1997 | B-cell NHLs: 100 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 1/100 (1%) | In-Hospital patients with nonhematologic malignancies, treated at the Princess Margaret Hospital | 1/100 (1%) | 1 (0-3) | No association between hepatitis C and B-cell lymphoma |

| Cowgill KD Int J Epidemiol 2004 | Case-control study Period: October 1999- and January 2003 | B-cell NHL: 220 NHL classification: NR | Total: 106/220 (48.1%) (1) anti-HCV+/RNA- 12/220 (5.4%) (2) anti-HCV+/RNA+ 94/220 (42.7%) | In-Hospital patients with fractures, treated at the Kasr El-Aini Orthopaedic Hospital, | Total: 80/222 (36%) (1) anti-HCV+/RNA-28/222 (12.6%) (2) anti-HCV+/RNA+ 52/222 (23.4%) | 48.2 (41.5-54.7) | Strong association between chronic HCV infection and risk of developing NHL, persisting after adjustment in multivariate models and after several sensitivity analyses |

| Cucuianu A Br J Haematol 1999 | Case series with control group Period: December 1997 and March 1999 | All B-cell NHL: 68 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 20/68 (29.5%) | Non-hospitalized Romanian individuals | 46/943 (4.9%) | 9.1 (5.3-12.9) | Detection of high prevalence (29.5%) of anti-HCV in patients with NHL, especially in low-grade types |

| De Renzo A Haematologica 2002 | Case-control Period: NR | All LPDs: 227 -B-cell LPds: 127 -HL 100 NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) histological scheme | B-cell LPds: 22/127 (17.3%) B-NHL 12/61(19.7%) MM 4/48 (8.3%) WM 4/9 44.4%) CLL 2/9 (22.2%) | A group of occasional blood donors from the same geographical area, studied as healthy controls | -HL 2/100 (2%) -Controls: 2/110 (1.8%) | 19.7 (9.7-29.6) | Detection, in Southern Italy, of a higher prevalence of HCV infection in patients suffering from B-LPD in comparison with healthy subjects, particularly in patients with B-cell-NHL, CLL and WMc |

| De Renzo A Euro J Haematology 2008 | Case series Period: 1990-2005 | All NHLs patients observed: 550 Primary hepatic lymphomas (PHL): 6 Primary splenic Lymphomas (PSL): 19 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | PHL: 4/6 PSL: 13/19 | NR | NR | PHL 66.7 (22.3-95.7) PSL 68.4 (43.5-87.4) | High prevalence of HCV infection among patients with rare haematologic malignancies (PHL and PSL ), favourable outcome of these subjects |

| De Rosa G Am J Hematol 1997 | Case series with control group Period: November 1994 -November 1995 | All Lympho-prolipherative Disorders (315): (1) No-B LPD: 52 HD: 43 (1 HCV+) T-NHL: 9 (2) B LPD: 272, including; NHL- B-cell lymphoma, CLL, HCL, MGUS, WMc, MM, ( 59 HCV+) NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-cell NHL: 21/91 (23.1%) | (1) Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (2) Healthy blood donors | (1) 1/43 (2.3%) 0/9 (2) 30/1568 (1.9%) | 23.1 (14.4-33.7) | Detection of a higher prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies patients with B-Lymphoprolipherative disorders, as compared to the normal population and to patients with a non-B-lymphoprolipherative disorders |

| De Vita S Br J Cancer 1998 | Case-control study Period: January 1994-June 1997 | All malignancies 84 NHLs NHL classification: Working Formulation | 20/84 (23.8%) | Controls recruited at Aviano, with cancers in: ovary: 13 uterus:14, colon-rectum:13, pancreas:10, lung: 8, stomach: 6, oesophagus: 4 other sites: 5 HCC: 27 | Controls: 3/73 (4.1%) HCC: 11/27 (40.7%) | 23.8 (15.2-34.3) | Detection of a higher than expected prevalence of HCV infection in B-cell NHL patients |

| Duberg AS Hepatology 2005 | Nationwide cohort of HCV-infected persons Cancer Registry used to identify all incident cancers diagnosed in the cohort malignant NHL Period: 1990-2000 | All malignancies: Patients with B-Cell NHLs, after exclusion of patients with HIV coinfection: 16 CLL: 4 MM:7 ALL: 1 HL: 1 NHL classification: NR | B-Cell NHLs: 16 in 27150 HCV positive patients included in the cohort, HCV infection diagnosis made to the Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control (SMI) | NR | NR | 0.06 (0.04-0.1) | A significantly increased risk of NHL and MM observed in this study, although an underestimation of the risk may have been caused by the delayed diagnosis of HCV |

| Ellenrieder VJ Hepatol 1998 | Case series Period: 1991- 1995 | B-cell NHLs: Low-grade B-cell NHL: 55 High- low-grade B-cell: 14 NHL classification: Kiel Classification | 3/69 (4.3%) CLL: 1/14 CC: 0/4 CB: 1/14 CCBC: 1/19 IC = 0/18 | NR | NR | 4.3 (0.9-12.2) | No aetiological role of HCV in the development of NHL in German |

| El-Serag HB Hepatology 2002 | Cohort study Period: 1992- 1999 | Identification of LNHs cases by means of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes NHL classification: NR | 421/34204 (1.23%) | 34204 HCV positive patients and 136816 randomly selected patients without HCV (controls) | 1669/136816 (1.22%) | 1.23 (1.1-1.3) | Significant high association between HCV infection and NHL, after adjustment for age |

| Engels EA Int J Cancer 2004 | Case-control study Period: July 1998-June 2000 | All NHL subtypes: (1) 32/813 (3.9%) (2) Low-grade B-cell NHL 18/411 (4.4%) (3) Intermediate-and high-grade B-cell NHL 8/275 (2.9%) (4) T-cell NHL 2/50 (4.0%) (5) other/unknown 4/77 (5.2%) NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) histological scheme | 26/686 (3.8%) | Eligible cases and controls sampled from individuals 20-74 yr old, prospectively identified by using Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) | 14/684 (2.1%) | 3.8 (2.3-5.2) | Detection of an association between HCV infection and NHL in the United States. HCV infection may be a cause of NHL |

| Ferri C Br J Haematol 1994 | Case series with control group Period: NR | B-cell NHL: 50 NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-cell NHL: 17/50 (34%) | (1) Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (2) Healthy subjects (3) anti-HCV negative patients with type B or delta chronic active hepatitis | 1/30 (3%) 30 15 HCV prevalence in in the healthy Italian population: 1.3% | 34 (20.8-47.1) | Presence of HCV infection in a substantial number of unselected NHL patients, particularly in comparison with HCV prevalence in control groups and in healthy Italian population |

| Franceschi S Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011 | Nested case-control study Period: standardized lifestyle and personal history questionnaires collected between 1991 and 2000. Vital status followed up to 2004 and 2006 | All lymphomas: 1023 cases NHL: 739 MM: 238 HL: 46 HCV positive: 12/1023 (1.17%) NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | B-cell NHLs: 628/1023 (61.4%) Number of HCV positive patients in B-NHLs not reported 9/730 HCV positive patients in all NHLs 14/1454 HCV positive in controls HL: 2/46 (4.3%) MM: 1/238 (0.4%) | Lymphoid tissue Malignancies classified according to the second revision of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-2) and to the WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Third Edition | 18/2028 controls (0.9%) | 61.4 (58.4-64.3) | The present study neither weakened nor strengthened the evidence of an association between HCV and NHL or other lymphoid tissue malignancies |

| Gentile G Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996 | Hospital-based case-control study of risk factors for acute leukemias Period: 1 November 1986 - 31 March 1990 | All acute leukemias: 430 Diagnosis performed by means of: French-American-British classification of bone marrow aspirates for acute leukemias and RAEB, whereas diagnosis for CML was based on typical dinical and cytogenetic laboratory features | All acute leukemias: 27/430 (6.3%): AML: 15/172 (8.7%) ALL: 5/67 (7.5%) CML: 2/125 (1.6%) RAEB: 5/66 (7.6%) | Controls recruited in the region of the three hospitals (Rome, Bologna, Pavia) during the study period among outpatients without hematobogical malignancies who were seen in the same hospitals at which cases had been identified | 44/857 (5.1%) | 6.3 (3.9-8.5) | Association between acute leukemias, RAEB, and CML Possible association between hepatitis B virus, AML, RAEB, and CML, but further confirmation required |

| Genvresse I Ann Hematol 2000 | Case series Period: 1995-2000 | All lymphomas: 119 (1) B-NHLs: 105 (2) T-NHLs: 14 NHL classification: REAL histological scheme | (1) 2/105 (1.9%) (2) 0/14 | NR | NR | 1.9 (0-4.5) | Possible HCV involvement in NHLs development via a continuous antigenic stimulation, leading to a B-cell clonal expansion |

| Germanidis G Blood 1999 | Case series with control group Period: January 1994 -July 1997 | B-NHL: 201 HD: 94 NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) histological scheme | B-NHL: 4/201 (2%) | Hematologic malignancies different from B-cell NHL (HD) | 1/94 (1.1%) | 2 (0-3.9) | No existence of a significant relationship between HCV infection and B-NHL in France |

| Giordano TP JAMA 2007 | Cohort study Period: 1997-2004 | Identification of LNH cases by means of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes NHL classification: NHL (200, 202.0-202.2, 202.8), WMc (273.0, 273.3), HL (201), MM (203.0-203.1, 238.6), ALL (204.0), CLL (204.1) AnLLs 205.0, 206.0), CML (205.1), other leukemia (204.2, 204.8-204.9, 205.2, 205.8-205.9, 206.1-206.2, 206.8-206.9, 207.8, 208.0-208.2, 208.88.9), MGUS (273.1, 273.2) | HCV- positive cohort: 146394 patients During follow-up, 813 patients in HCV-infected cohort (0.5%) had a HIV diagnosis NHL: 319 HL: 65 MM: 95 CCL:69 ALL: 27 WMc: 67 CML: 30 | Inpatients records from more than 150 United States Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in the Patients’ treatment file and outpatients records from any VA facility in the Output Clinic File | HCV- negative cohort: 572293 patients. During follow-up, 35696 uninfected HCV patients (6.2%) had a recorded HCV diagnosis and 1539 patients (0.3%) a HIV diagnosis NHL: 1040 HL: 295 MM: 431 CCL:343 ALL; 184 WMc: 98 CML: 163 | 0.2 (0.19-0.25) | An increased risk of: (1) non-Hodgkin lymphoma overall (20%-30%), (2) Waldenström macroglobulinemia, a low-grade lymphoma (3-fold higher risk), (3) cryoglobulinemia, in subjects with HCV infection. An etiological role for HCV, in causing lymphoproliferation and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, supported by these results |

| Goldman L Cancer Causes Control 2009 | Case-control study Period: October 1999 -March 2004 | All lymphomas: 139/296 (47% ) -T-NHL: 8/24 (34.8%) -DLBCL:79/146 (54.9%) -MZL: 14/24 (58.3%) -CLL: 24/58 (41.4%) -FC: 9/23 (40.9%) -MCL: 5/16 (31.3%) NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | B-NHL: 131/272 (48.2%) | Cancer-free subjects, sampled from the Kasr El Aini Faculty of Medicine Orthopaedic Hospital in Cairo | 283/786 (37.4%) | 48.2 (42.2-54.1) | HCV is a risk factor for diffuse large B cell, marginal zone, and follicular lymphomas in Egypt |

| Guida M Leukemia 2002 | Case-control study Period: September 1999-October 2001 | All Lymphomas: 12/60 (20%) MM: 5/60 B-NHL: 55/60 NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-NHL: 12/55 (21.8%) | Control patients with non-hematological malignancies recruited from the Surgery Department the Oncology Institute of Bari (Italy) | 9/63 (14.2%) | 21.8 (10.9-32.7) | Moderate increase of prevalence of HCV infection among patients with B cell lymphoproliferative disorders in a very homogeneous population of southern Italy |

| Hanley J Lancet 1996 | Case series Period: NR | All LPDs: 72. B-cell NHLs: 38 MM: 24 MGUS: 10 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 0/72 | NR | NR | 0 (0-4.9) | No association between chronic HCV infection and risk of NHLs development |

| Harakati MS Saudi Med J 2000 | Case series with control group Period | B-cell NHLs: 56 patients NHL classification | B-NHL: 12/56 (21.4%) | (1) Blood donors and general medical patients) (2) Other hematologic malignancies other than B-cell NHL | (1) 3/104 (3%), (2) 2/41 (5%) | 21.4 (10.6-32.7) | Higher prevalence of Hepatitis C virus infection in Saudi Arab patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma than in the control groups |

| Hausfater P Am J Hematol 2001 | Prospective controlled study Period: June to September 1998 | All LPD: 394 B-NHL: 164 HD: 34 CLL: 107 MM: 54 WMc:12 NHL classification: NR | B-NHL: 3/164 (1.8%) | (1) In-Hospital patients without cancers (2) Nonmalignant hematological diseases (3) Hematological malignancies other than B-cell NHL | (1) 3/694 (0.43%) (2) 8/224 (3.6%) (3) 9/425 (2.1%) | 1.8 (0-3.8) | No increased prevalence of HCV infection in patients admitted to the Hematology department for B-NHL. No major pathophysiologic role of HCV in lymphoproliferative disorders in Paris |

| Hwang JP J Oncol Pract 2014 | Cohort-study Period: January 2004 -April 2011 | Patients’data, obtained from four institutional sources: Tumor registry: to assess patients’ demographic characteristics Pharmacy informatics: to evaluate chemotherapy drugs and dates administered. Patient accounts: to identify study patients’ International Classification of Diseases (ninth edition; ICD-9) codes Laboratory informatics: to determine HCV antibody (anti-HCV) and ALT test dates and results | 141877 patients with cancer, who were newly registered at MD Anderson Cancer during the study period. Patients considered in the study: 16, 773. HCV screened subjects: 1628/16773 (9.7%) with NHLs, 1400 patients with anti-HCV test 42 NHLs antiHCV-positive (3%) | NR | NR | 3 (2.1-3.9) | HCV screening rates were low, even among patients with risk factors, and the groups with the highest rates of screening did not match the groups with the highest rates of a positive test result |

| Imai Y Hepatology 2002 | Cohort study Period: February 1992 -July 1992 | NHLs: 187 B-cell NHLs: 156 T-cell NHL:31 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | 21/156 (13.5%) | Use of screening data of 197600 first-time voluntary blood donors to the Osaka Red Cross Blood Center | Expected numbers of anti- HCV-positive patients with NHL categorized by gender and phenotype in general population: 4.64 | 13.5 (8.1-18.8) | A significantly higher frequency of HCV infection in B cell NHL in comparison with that in birth cohort- and sex-matched blood donors; chronic HCV infection may be associated with B-cell NHL in Japan |

| Isikdogan A Leuk Lymphoma 2003 | Case series with control group Period: December 1997-September 2001 | NHLs: 119 High-grade NHLs: 10 Intermediate-grade: 64 Low-grade: 45 NHL classification: Working formulation | 0/119 | Subjects admitted as outpatients at Internal Medicine of Dicle Univeristy, Diyarbakir, without history of haematological disordres, during the same period | 117 | 0 (0-3) | No relationship between HCV and NHLs in the Southeastern Anatolia of Turkey |

| Iwata H Haematologica 2004 | Hospital-based case control Study Period: 1995-2001 | All NHLs: 145, 140 with anti-HCV test NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | 16/140 (11.4%) | Randomly selected controls from patients admitted to the (1) orthopedics (290 patients, 286 with anti-HCV markers) or (2) ear, nose and throat (284 patients, 282 with anti-HCV markers) departments of the hospital | (1) 9//286 (3.1%) (2) 20/282 (7%) | 11.4 (6.1-16.7) | Significant association between HCV infection, and malignant lymphoma by multivariate analysis |

| Izumi T Blood 1996 | Case series Period: 1992-1997 | All lymphomas: 83 patients, B-cell NHLs: 54 Non-B-cell NHLs: 20 HLs: 9 NHL classification: NR | B-cell NHLs: 12/54 (22.2%) Non-B-cell NHLs: 0/20 HLs: 0/9 | NR | NR | 22.2 (11.2-33.3) | Direct causal relationship between the occurrence of PHSL and chronic HCV infection |

| Izumi T Leukemia 1997 | Case series Period: NR | B-cell LPDs: 50 patients B-cell NHLs: 25 MM: 21 WMc: 4 NHL classification: NR | 4/25 (16%) | NR | NR | 16 (4.5-36.1) | Association between HCv infection and B-cell NHLs |

| Karavattathayyil SJ Am J Clin Pathol 2000 | Case series Period: January 1993-December 1996 | Patients with B-cell NHLs: 31 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification | Positive HCV-RNA strands: 8/31 (25.8%) Negative HCV-RNA strands: 6/31 (19.4%) | (1) T-cell NHLs: 2 cases (2) HL: 2 cases (3) Patients with lymph nodes removed for reasons other than lymphoma: 28 | 0/32 | Positive HCV-RNA strands: 25.8 (10.4-41.2) Negative HCV-RNA strands 19.4 (5.4-33.2) | Presence of HCV infection in a significant percentage of paraffin-embedded tissue from B-cell NHLs patients, compared with control subjects; detection of negative-strand RNA suggests HCV replication in these tissues, excluding the possibility of contamination with viral RNA or blood |

| Kashyap A Ann Intern Med 1998 | Case series with control group Period: February 1992-December 1995 | All NHLs: 312 36 HCV positive patients NHL classification: NR | NHLs: 36/312 (11.5%) | (1) Healthy United States blood donors (2) Black and Hispanic patient population at City of Hope National Medical Center | (1) (0.4%) (2) approximately 25% | 11.5 (8-15.1) | Prevalence of HCV positivity is still much higher than expected, even after adjustment for differences in patient demographic characteristics |

| Kaya H Clin Lab Haematol 2002 | Case-control study Period: NR | All NHLs: 70 patients Low-grade NHLs: 22, Intermediate- grade NHLs: 17 high-grade NHLs: 31 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 1/70 (1.4%) | Healthy-subjects admitted at Departments of Haematology, Ataturk University, Erzurum | 1/70 (1.4%) | 1.4 (0-4.2) | No aetiologic role of HCV in NHL development |

| Kim JH Jpn J Cancer Res 2002 | Case-control study Period: January 1997 -December 1998 | NHLs: 233 patients 214 patients with anti-HCV positivity NHL classification: Working Formulation | 7/214 (3.3%) | Control groups comprised patients with (1) non-hematological malignancy (control group 1) and subjects with (2) non-malignant conditions (control group 2) diagnosed at Seoul National University Hospital during the same period. For each case, four controls selected | (1) 7/426 (1.6%) (2) 12/439 (2.7%) | 3.3 (0.8-5.6) | No association between NHL and HCV infection |

| King PD Clin Lab Haematol 1998 | Case series series with control group Period: June 1995-May 1997 | All lymphomas: 93 patients. NHLs: 73 patients HL: 20 patients 438 HCV positive patients NHL classification: Working Formulation | 1/73 (1.4%) | Patients with HL admitted at Department of Gastroenterology, University of Missouri Hospital | 0/20 1/438 (0.22%) patients developed NHL | 1.4 (0-4) | No association between NHL and HCV infection |

| Kocabaş E Eur J Epidemiol 1997 | Case series with control group Period: October 1993-March1994 | 137 Children with malignancies: Acute leukemia: 48 Lymphoma: 51 Solid tumours: 38 NHL classification: | 8/137 children were anti HCV positive, 129 patients were anti- HCV negative, but 7/129 were HCV-RNA positive | Children admitted, at Balcah Hospital, Adana, during the same period with diseases other than malignancies | 1/45 | 5.8 (1.9-9.7) | HCV infection is common among Turkish children with different types of cancer |

| Kuniyoshi M J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001 | Case-control Study Period:January 1990-March 1998 | NHLs 348 patients 20/348 (8.1%) HCV positive patients with NHLs NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-cell NHLs: 15/348 (4.3%) | 1658234 blood donors, representing general population in the area (Fukuoka, Japan) | 11922/1658234 (0.72%) | 4.3 (2.1-6.4) | Involvement of HCV infection in the development of a subgroup of NHL, in males |

| Luppi M Ann Oncol 1998 | Case series Period: January 1989-August 1993 | B-cell NHLs: 157 patients NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) histological scheme | 35/157 (22.3%) HCV positive B-cell NHLs: LDBCL 8/35 (23%) FC: 14/35 (40%) LPL: 2/35 (6%) 122/157 (67.7%) HCV negative B-cell NHLs | NR | NR | 22.3 (15.8-28.8) | Association of HCV infection with the malignant proliferation of defined B-cell subsets other than the immunoglobulin Mk B-cell subset involved in the pathogenesis of mixed cryoglobulinemia type II and associated lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma type |

| Markovic Hepato-Gastroenterology 1999 | Case-series Period: January 1991-April 1996 | All lymphomas: 305 patients NHLs: 300 patients HL: 5 patients 181 patients with anti-HCV test NHL classification: NR | 3/181 (1.6%) | NR | NR | 1.7 (0-3.5) | No association between HCV infection and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, because of low HCV prevalence in Slovenia |

| Mazzaro C Br J Haematol 1996 | Case-series with control group Period: NR | All lymphomas: 199 patients Low-grade NHLs: 105 (52.7%) Intermediate grade NHLs: 48 (24.1%) High-grade: 39 (19.6%) MALT: 5 (2.5%) T-cell NHLs: 2 (1%) NHL classification: Working Formulation | 57/199 (28.6%) Low-grade NHLs: 40/110 (36.47%) Intermediate grade NHLs: 6/48 (12.5%) High-grade: 9/39 (23.1%) | (1) Patients with other haematological malignancies, including HL (21 patients), CLL (41), myelodysplastic syndrome (72), plasma cell myeloma (19); (2) general population of two towns in the same geographical area (Cormons and Campogalliano) in the cohort study called Dyonisos project | (1) 5/153 (3.1%) (2) 199/6917 (2.9%) | 28.6 (22.4-34.9) | Important role of HCV in the development of low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas |

| McColl MD Leuk Lymphoma 1997 | Case series Period: NR | B-Cell NHL: 72 patients Low-grade: 41 Intermediate-grade: 23 High grade: 8 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 0/72 | Patients with CLL, recruited at two Hospital in the West of Scotland | 0/38 | 0 (0-9.2) | Possible role of HCV infection in the aetiology of certain subgroups of NHLs, although this effect may be regional |

| Mele A Blood 2003 | Multicenter case- study with control group Period: 1998-2001 | B-Cell NHL: 400 patients NHL classification: REAL/World Health Organization classifications | 70/400 (17.5%) Aggressive B-NHL: 43/230 (18.7%) Indolent NHL:27/170 (15.9%) | Patients recruited n other departments of the same Hospitals: the departments of dentistry, dermatology, general surgery, gynecology, internal medicine, ophthalmology, orthopedics, otorhinolaryngology and traumatology | 22/396 (5.6%) | 17.5 (13.8-21.2) | Detection of an association between HCV and B-NHL |

| Mizorogi F Intern Med 2000 | Case series with control group Period: January 1993-December 1998 | Patients with LPDs: 161, subdivided into 2 groups: (1) patients with B-cell LPDs, including B-cell-NHLs: 100 MM: 17 CLL: 4 (2) patients with non B-cell LPDs: 38 NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-cell NHLs: 17/100 (17%) | Subjects with miscellaneous diseases other than liver diseases or LPDs, used as controls | nonB-cell LPDs: 0/25 34/516 (6.6%) | 17 (9.6-24.3) | Higher prevalence of HCV infection in patients with B-cell NHL than in those with non-B-cell NHL and the control group, frequent primary liver involvement and liver-related causes of death in HCV-positive patients with B-cell NHL |

| Montella M Leuk Res 2001 | Case-control study Period: January 1997 and December 1999 | -B-cell-NHLs: 101 -HL: 63 -T-cell NHLs: 10 -MM: 41 NHL classification: Working Formulation/REAL | 25/101 (24.8%) | Controls: patients with no history of malignant tumor, admitted to the National Cancer Institute and Cardarelli Hospital of Naples, in the same period | -Controls: 17/226 (8%) -HL: 6/63 (10%) -T-cell NHLs: 3/10 (30%) -MM: 13/41 (32%) | 24.8 (16.3-33.1) | Detection of a significant association between HCV infection and B-cell NHLs in the extranodal localization, and also indicate an association for the nodal seat |

| Morton LM Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004 | Population-based case-control study of women in Connecticut The Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Rapid Case Ascertainment Shared Resource (RCA), a part of the Connecticut Tumor Registry (CTR), a population-based tumor registry Period: 1995-2001 | All lymphomas: B cell 362 T cell 34 Others: 60 NHL classification: World Health Organization classification Incident cases of NHL identified by means of (ICD)-O: M-9590-9595, 9670-9687, 9690-9698, 9700-9723 | B cell 7/362 (1.9%) T cell 0/4 Others 1/60 (1.6%) Total: 8/464 (2%) | A population-based control group of female residents of Connecticut, aged 21-84, assembled using two methods:-Random digit dialing used to contact women less than 65 yr of age,-random selection from the files of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for women aged 65 yr and older | 5/534 (1%) | 1.9 (0.5-3.3) | Indirect HCV involvement in the development of B-NHL, this risk varying by B-NHL subtype among women |

| Musolino C Haematologica 1996 | Case series Period: NR | All-NHLs:24 HCV positive: 2 patients HCV-RNA positive: 5 patients NHL classification: Working Formulation | 5/24 HCV-RNA positive/NHLs | NR | NR | 20.8 (7.1-42.2) | Possible HCV involvement in NHL development |

| Musto P Blood 1996 | Case series with control group Period: NR | B-LPDs B-NHL: 150 HCL: 9 CLL: 41 MM: 90 WMc:13 MGUS: 47 NHL classification: NR | B-NHLs: 40/150 (26.7%) HCL:1/9 (11.1%) CLL: 8/41 (19.5%) MM: 10/90 (11.1%) WMc: 3/13 (23%) MGUS: 6/47 (12.8%) | Patients hospitalized for acute trauma | 25/466 (5.4%) | 26.7 (19.6-33.7) | A significantly higher prevalence of anti-HCV in patients with B-NHLs than in controls and independent of age |

| Nicolosi Guidicelli S Hematol Oncol 2012 | Case-control study Period: July 2001 to March 2002 | All lymphomas: 137 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 6/137 (4.4%) | Patients observed in Hospital Clinic, Barcelona and San Giovanni Hospital, Bellinzona, (ideally in traumatology and orthopaedic divisions | 7/125 (5.6%) | 4.4 ( 0.9-7.8) | Existence of marked geographic differences in the prevalence of HCV in NHL but no significant evidence for an association between HCV and B-cell NHLs |

| Nieters A Gastroenterology 2006 | European Multicenter Case-Control Study Period: 1998-2004 | Total Lymphomas: 1807 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 53/1807 (2.9%) | Controls drawn randomly from population registers of the study regions in Germany and Italy. In the remaining countries, controls recruited from the same hospital as cases | 41/1788 (2.3%) | 2.9 (2.1-3.7) | Positive association between HCV infection and B-cell lymphoma and a role of viral replication in lymphomagenesis |

| Ogino H Hepatol Res 1999 | Case-control sudy Period: 1991-1997 | All LPDs: 43 patients NHLs: 33 ALL: 10 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 4/33 (12.1%) | (1) 45 patients, undergoing colonscopy from July 1995 to June 1996 (2) 10599 healthy subjects, receiving a general medical check-up in Toyama prefecture from April 1996 to March 1997 | 2/45 (4.4%) | 12.1 (3.4-28.2) | High prevalence of HCV infection in patients with NHL in Toyama prefecture in Japan |

| Ohsawa M Int J Cancer 1999 | Cohort-study Period: 1957-1997 | Patients with HCV chronic infection, included in the present study: 2162 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | Patients developing B-cell NHLs: 4/2162 During follow-up | Expected number of cases of NHLs in the sex-, age- and calendar year-matched general population: 1.90 | NR | 0.2 (0-0.3) | Chronic HCV infection moderately associated with increased risk of NHL |

| Okan V Int J Hematol 2008 | Case series with control group Period: NR | All Lymphomas: 334 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 9/334 (2.7%) MM: 1/67 (3.1%) CLL: 2/78 (2.5%) DLBCL: 4/67(6%) Follicular 0/9 Mantle: 1/11 (9%) Other: 0/26 T-cell lymphoid tumors: 1/16 (6.2%) HL: 0/60 | Controls recruited, using records from the University blood center in Gaziantep | 9/802 (1.1%) | 2.7 (0.9-4.4) 6 (0.3-11.6) | Higher HCV- seropositivity rate in patients with DLBCL in comparison with controls. No significant differences in the prevalence of HCV seroposity between patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and controls |

| Omland LH Int J Cancer 2012 | Cohort-study Period:1991-2006 Patients and subjects with HCV infection identified by means of: -Danish HCV cohort (DANVIR). -Civil registration system (CRS)-Danish cancer registry (DCR). -Danish national patient registry (DNPR) | 10 digit civil registration number assigned to all individuals in Denmark Analysis of the association between HCV and risk of NHL (ICD-10 codes: C82.0-85.9 and C96) NHL classification: Cancers classified according to the "International Classification of Diseases" 7th revision (ICD-7) for the period 1943-1977 and the 10th revision (ICD-10) for the period 1978-2006 | -11975 anti- HCV-positive patients LNH cases detected: 12 12/11975: 0.1% | Comparison cohort, which consisted of 6 age- and gender-matched individuals (without a HCV diagnosis) from the general population randomly selected from the CRS, on the day HCV-infection was diagnosed in the corresponding DANVIR cohort member | -71850 anti- HCV-positive patients LNH cases detected: 24 | 0.1 (0.04-0.15) | Possible increased risk of NHLs in patients with chronic HCV infection |

| Panovska I Br J Haematol 2000 | Case-series with control group Period: NR | B-cell-NHLs: 112 NHL classification: REAL histological scheme | 1/112 (0.9%) | Patients with other B-cell malignancies HL: 38 CLL: 43, ALL: 9 MM: 26 WMc: 1 Prevalence of HCV carriers in Republic of Macedonia within the general population is equal to 2.0% | 1/137 (0.72%) | 0.9 (0-2.6) | Low prevalence of HCV infection in patients with B-cell NHL from Macedonia and a lack of association between the two disorders |

| Park SC J Med Virol 2008 | Case-control study Period: January 1998- December 2001 | 235 patients with NHLs, B-cell subtypes: 168 T-cell subtypes: 57 not identified subtypes: 10 NHL classification: NR | 5/235 (2.1%) No information about number of patients with HCV infection and B-NHL cases | Patients with advanced gastric cancer diagnosed at the Korea Cancer Center Hospital | 7/235 (3%) | 2.1 (0.3-3.9) | No association between HCV infection and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Paydas S Br J Cancer 1999 | Case series Period: NR | LPDs: 228 patients NHL: 98 CLL: 38 MM: 47 HD: 36 ALL: 9 NHL classification: NR | NHL: 9/98 (9.2%) CLL: 4/38 (10.5%) MM: 5/47 (10.6%) HD: 7/36 (19.4%) ALL: 1/9 (11.1%) | NR | NR | 9.2 (3.4-14.9) | HCV infection as a causative and/or contributing factor in lymphoproliferation in this study |

| Pellicelli World J Gastroenterology 2011 | Case-series Period: January 2008 -January 2009 | 125 patients with B-cell NHLs NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 24/125 (19.2%) | NR | NR | 19.2 (12.3-26.1) | HCV genotypes and duration of HCV infection differed between B-NHL subtypes. Indolent lymphomas can be managed with antiviral treatment, while DLBCL is not affected by the HCV infection |

| Pioltelli P Lancet 1996 | Case-series with control groups Period: January-June 1995 | All Lymphomas: 204 NHLs: 126 HL: 78 28HCV positive lymphomas NHL classification: Working Formulation | 26/126 (20.6%) | (1) HL (2) candidated blood donors (3) elderly people | (1) 2/78 (2) 9/832 (3) 9/94 | 20.6 (13.5-27.7) | High prevalence of HCV infection in NHLs, in the absence of an increased risk for HCV infection and of a clinical history of MC |

| Pioltelli P Am J Hematol 2000 | Case-control study Period: 01/01/96-30/06/97 | Patients with B-cell NHLs: 300 NHL classification: Working Formulation (WF) and REAL histological scheme | 48/300 (16%) | Individuals consecutively recruited during routine visits at medicine, surgery, or traumatology departments during the recruitment period of the study population (1) Patients with internal and surgical diseases (2) Patients with solid neoplasm (3) Patients with autoimmune disorders | (1) 51/600 (2) 15/247 (3) 6/122 | 16 (11.8-20.1) | The prevalence of HCV infection is higher in patients with NHLs than in non-neoplastic people and in patients with non-lymphoproliferative malignancies or receiving immunosuppressive treatment, but the small difference among these groups, the identical genotype pattern between NHL and controls do not support the hypothesis that HCV plays a role in lymphomagenesis |

| Pivetti S Br J Haematol 1996 | Case-series with control group Period: NR | Patients with LPDs: 167 patients (30 HCV positive) HL: 30 NHLs: 47 CLL: 29 MM: 18 MGUS: 31 WMc: 12 NHL classification: NR | 7/47 (14.9%) | (1) Patients with connective tissue diseases (2) Patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | (1) 26/100 (26%) (2) 12/33 (36.4%) | 14.9 (4.7-25) | HCV may link lymphoid malignancies and autoimmune diseases by skewing the activity of the immune system toward the production of autoAbs |

| Pozzato G Blood 1994 | Case series Period: NR | 31 patients with MC. 12 patients/31 with low-grade NHLs 26/31 HCV positive NHL classification: Working Formulation | 10/12 patients with low-grade NHLs were anti-HCV positive | NR | NR | 83.3 (51.6-97.9) | HCV associated with a high prevalence of low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas |

| Prati D Br J Haematol 1999 | Case series Period: January 1989 -August 1998 | Primary cutaneous B-cell NHL. NHL classification: European Organisation for Research and Therapy of Cancer (EORTC) | 1/34 (2.9%) | NR | NR | 2.9 (0-8.6) | Primary cutaneous B-cell NHL might represent a distinctive group among B-cell NHLs |

| Rabkin CS Blood 2002 | Cohort study Period: June 1959 and September 1966 | All LPDs: 95 B-cell NHL: 57 MM: 24 HL: 14. NHL classification: Tumors classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, second edition, as NHL (histologic classifications 9590 through 9642 and 9670 through 9698), multiple myeloma (9730 through 9732), or Hodgkin disease (9650 through 9667) | 4/95 (4.2%) 0/95 at RIBA 0/95 at HCV-RNA | Study subjects (48 420 individuals) recruited from the Child Health and Development Study (CHDS) cohort established in 1959 at the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Oakland, CA | 1/48.420 at ELISA 0/48420 at RIBA | 4.2 (0.1-8.2) | Not substantial role of chronic HCV infection in the etiology of B-cell neoplasia |

| Ramos-Casals M J Rheumatol 2004 | Case series Period: 1994-2000 | NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 6/98 | NR | NR | 6.1 (1.3-10.8) | Description concerning a triple association of HCV infection, autoimmune diseases and NHLs |

| Salem AK Gulf J Oncol 2009 | Case series with control-group Period: January 2005-January 2007 | All NHLs: 192 patients NHL classification: NR | 29/192 (15.1%) | Patients checked for HCV infection with several acute medical conditions and coming from different parts of the country | 814/20329 (4%) | 15.1 (10-20.1) | Higher prevalence of HCV infection among Yemeni patients with NHL than among persons in the control group |

| Salem Z Eur J Epidemiol 2003 | Case-series with control group Period: NR | B-cell NHL: 35 patients. NHL classification: NR | 0/35 | (1) Patients with different malignancies (malignant myeloproliferative disorders: 12, malignant lymphoproliferative disorders: 28, non haematological cancers: 23 patients) (2) Healthy blood donors and patients without malignant conditions, attending General Medicine of American university, Beirut | (1) 0/63 (2) 0/220 | 0 (0 -10) | No association between HCV infection and B-cell NHLs development in Lebanese patients |

| Sansonno D Blood 1996 | Case series Period: January 1991 to December 1995 | 12 HCV-positive patients with MC and 2 HCV-positive patients with reactive lympho-adenopaties NHL classification: Working Formulation | 3/12 (25%) | NR | NR | 25 (0.5-49.5) | These data emphasize that lymphoid organs may be a site of HCV infection. The demonstration of HCV-related proteins in a nonmalignant condition, namely HRL, indicates that HCV infection precedes the neoplastic transformation and possibly plays a major role in lymphomagenesis in MC |

| Schöllkopf C Int J Cancer 2008 | Nation-wide Danish-Swedish case-control study (Scandinavian Lymphoma Etiology study, SCALE) Period: The SCALE study population includes the entire Danish population between June 1, 2000 - August 30, 2002, and the Swedish population between October 1, 1999-April 15, 2002 | All lymphomas: 2819 NHLs: 2353 HL: 466 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | HCV positive NHLs: 57 (2.4%) HL: 6 (1%) at III G ELISA test,only NHLs: 7/2353 (0.7%) HL: 0 positive at ELISA test and positive or intermediate at RIBA test for anti-HCV antibodies | Controls randomly sampled from the entire Danish and Swedish populations using continuously updated, computerized population registers | 21/1856 (1%) | 2.4 (1.8-3) | Positive association between HCV and risk of NHL, in particular of B-cell origin |

| Seve P Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004 | Cross-sectional study Period: January 1997-December 1998 | B-NHL:212 patients BL 6 DLBCL 109 FC 31 LL 7 LPL 5 MALT 17 MCL 21 MZL16 NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification | (1) 6/212 (2.8%) (2) MALT 3/17 | Transfusion patients from surgical emergency, internal medicine pneumology, endocrinology, gastroeterology, nephrology, oncology, general surgery, orthopaedics, rheumatology, obstetrics and gynaecology, and intensive care wards | 20/974 (2.05%) | (1) 2.8 (0.6-5) (2) 17.6 (3.8-43.4) | Possible association between HCV and MALT lymphoma |

| Shariff S Ann Oncol 1999 | Case series with control group Period: 1996 and part of 1997 | patients with B-cell NHL NHL classification: Working Formulation/Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification | 2/88 (2.3) | (1) patients with a T-cell NHL (2) second control group, including health-care workers, recruited between 1995 and 1997 | 0/37 11/1085 (1%) | 2.3 (0-5.3) | Chronic HCV infection as a risk factor for B-cell NHL in certain populations or with certain genotypes of the virus, no significant association in British Columbia |

| Shirin H Isr Med Assoc J 2002 | Case control group Period: May 1997 -September 1999 | B-NHL (DLCL FC CLL) NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification | Total: 212 patients Lymphoproliferative disorders: 10/128 (7.8%) | (1) Patients with Myeloprolipherative and myelodisplastic disorders: (2) Israeli blood donors | (1) 1/84 (1.1%) (2) HCV prevalence equal to 0.64% | 7.8 (3.1-12.4) | Significant association between HCV infection and diffuse large B cell lymphoma |

| Silvestri F Bood 1996 | Case series with control group Period: NR | 537 unsekected patients with LPDs B-cell NHLs: 311 T-cell NHLs: 57 MM: 78 HL:88 ALL: 23 NHL classification: Kiel classification/Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification | 29/311 (9%) | NR | T-cell NHLs: 2/57 (4%) MM: 3/78 (4%) HL:0/88 ALL: 1/23 (4%) | 9 (6-12.5) | High prevalence of HCV infection in patients with B-cell NHL |

| Silvestri F Haematologica 1997 | Case series Period: NR | B-cell NHLs NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification | 42/470 (8.9%) 21/22 (95.4%) B cell-NHLs patients with cryo-globulinemia 21/448 (4.6%) B cell-NHLs patients without cryo-globulinemia | NR | NR | 8.9 (6.3-11.5) | Close association between HCV infection and B-cell NHLs |

| Singer IO Leuk Lymphoma 1997 | Case-series with control group Period: NR | All Lymphomas: 50 unselected patients B-cell NHLs: 31 T-cell NHLs: 6 HL: 13 NHL classification: Working Formulation | 0/31 | No information about control groups | 0/19 | 0 (0-11.2) | No evidence supporting an association between HCV infection and LNH development |

| Sonmez M Tumori 2007 | Case-control study Period: 2002-2005 | B-cell NHLs: 109 DLBCL: 71 Small-cell LL: 38 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 3/109 (2.8%) Low grade: 1/38 (2.6%) High grade: 2/71 (2.9%) | Patients selected from orthopedics, general surgery, urology, ophthalmology, otorhino-laryngology clinics with irrelevant diseases | 28/551 (5.1%) | 2.8 (0-5) | No difference in the incidence of HCV infection between NHL- and control- group |

| Spinelli JJ Int J Cancer 2008 | Population-based case-control study Period: March 2000 and February 2004 | All-NHL cases:795, from the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) and the Capital Regional District (CRD), including the city of Victoria, enrolled from the BC Cancer Registry NHL classification: World Health Organizations classification | NHLs: 19/795 (2.4%) B-cell NHLs:18/717 (2.5%) T-cell NHLs: 1/78 | Controls selected from the Client Registry of the BC Ministry of Health | 5/697 (0.7%) | 2.4 (1.3-3.4) | HCV infection contributes to increase NHL risk |

| Swart A BMJ Open 2012 | Cohort-study Period: 1 January 1993-31 December 2007 | Individuals registered on the Pharmaceutical Drugs of Addiction System, a record of all NSW Health Department authorities that administer methadone or buprenorphine to opioid-dependent people as opioid substitution therapy. Solid cancers classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th revision, haematopoietic neoplasms and Kaposi sarcomas classified according to the ICD for Oncology, 3rd edition | Patients considered in the study: 29613 Subjects with HCV infection alone: 14892 Observed number of LNH in HCV-positive cohort: 75 | Calculation of expected number of incident LNHs | Expected number of LNH: 49.6 | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | Association between HCV infection and LNHs |

| Takai S Eur J Haematol 2005 | Case series Period: January 1996 to September 200 | All haematological malignancies: 601 NHL: 218 DLBCL: 110 FCL: 100 MCL: 3 PTCL: 5 Acute Leukemia: 246 AML: 193 ALL: 53 Adult T-cell Leukaemia: 13 MM:124 | 37/601 patients were anti-HCV positive NHL: 22/218 (10.1%) DLBCL: 13/110 (11.8%) FCL: 8/100 (8%) MCL: 1/3 (33%) PTCL:1/5 (20%) AML: 5/193 (2.6%) ALL: 2/53 (1.8%) adult T-cell Leukaemia: 0/13 MM: 8/124 | NR | NR | NHLs: 10.1 (6.1-14.1) DLBCL: 11.8 (5.8-17.8) FCL: 8 (2.7-13.3) MCL: 33 (0-86.2) PTCL:20 (0-63) AML: 2.6 (0.4-4.8) ALL: 1.8 (0-8.9) MM: 6.5 (2.2-10.8) | High prevalence of HCV infection in NHL Possible role of HCV in the pathogenesis of NHs |

| Takeshita M Histopathology 2006 | Case series with control group Period: NR | All-Lymphomas: 537 (1) HL: 18 -B-NHL: 400 (DLBCL, FC CLL, MALT, PCM, MCL, MZL, BL, others) -T-cell NHL: 96 -NK/T-cell NHL: 23 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | B-cell NHL 45/400 (11.3%) Primary Effusion Lymph: 3/6 (50%) BL: 1/7 (14.3%) DLCL:28/161 (17.4%) FL: 3/47 (6.4%) MALTOMA: 5/52 (9.6%) MM: 4/81 (4.9%) CLL, SMZL, Mantle cell Lymp: 0 | (1) Other haematological malignancies (2) Blood donors | (1) HL: 1/18 (5.6%) T-cell NHL: 5/96 (5.2%) NK-Tcell Lymphomas: 2/23 (8.7%) (2) 396/15567 (2.5%) | 11.3 (8.1-14.3) | HCV infection may play a role in lymphomagenesis of splenic and gastric DLBCL |

| Talamini R Int J Cancer 2004 | Case-control study Period: January 1999 -July 2002 | Total NHL: 225 cases 44/225 HCV positive patients NHL classification: International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, updated to include categories in the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL)/World Heath Organization classification | 44/225 HCV positive patients 40/225 (17.8%) patients with B-cell NHLs (1) Low-grade B-cell: 24 (2) Intermediate- and high-grade B-cell: 16 (3) T-cell: 2 (4) Unknown:2 | Patients with a wide spectrum of acute conditions admitted at National Cancer Institute, Aviano; the “Santa Maria degli Angeli” General Hospital, Pordenone; the “Pascale” National Cancer Institute, Naples and 4 general hospitals, Naples | 45/504 (8.9%) | 17.8 (12.8-22.8) | HCV infection associated with an increased NHL risk |

| Teng CJ Clinics 2011 | Case series Period: 2003-2008 | MM: 155 patients 30 patients with chronic hepatitis MM diagnosis: International Myeloma Working Group | 14/155 (9%) 1/155 with HBV/HCV co-infection | NR | NR | 9 (4.5-13.5) | High prevalence of cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with HCV chronic hepatitis |

| Thalen DJ Br J Haematol 1997 | Case series Period: NR | NHLs: 115 patients B-cell NHLs: 99/115 (86%) T-cell NHLs: 15 (13%) Unclassified: 1 (1%) NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-cell-NHLs: 0/99 T cell NHLs: 0/15 | NR | NR | 0 (0-3.7) | No association between HCV infection and B-cell NHLs in the study |

| Timuragaoğlu A Haematologia 1999 | Case series with control group Period: NR | NHLs: 48 patients NHL classification: Working Formulation | Anti HCV positive: 0/48 HCV-RNA positive: 3/35 (8.6%) | Patients with various haematological disorders (MM, HL, acute myeloblastic leukaemia, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, chronic myelogenous leucemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, myelodysplastic syndrome) | 0/28 | 8.6 (1.8-23.1) | Association between HCV infection and B-cell NHLs in the study |

| Tkoub EM Blood 1998 | Case series with control group Period: NR | 46 patients with gastric MALT: High grade: 21 Low-grade 25 37/46 patients with Helicobacter Pylori NHL classification: NR | 1/46 (2.2%) | Patients with gastroduodenal disease: 84 with duodenal ulcer 43 with gastric ulcer 38 with dispepsia | 4/165 (2.4%) | 2.2 (0-6.3) | No link between HCV infection and gastric MALT in France |

| Tursi A Am J Gastroenterol 2002 | Case series Period: NR | 25 HCV positive patients with gastric MALT. -20/25 (80%) with grade 2-5/25 (20%) with grade 3. 18/25 patients with Helicobacter Pylori NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | NR | NR | NR | MALT grade 2: 80 (59.3-93.2) MALT grade 3: 20 (6.8-40.7) | HCV may colonize gastric MALT, allowing the development of a grade of acquired MALT, this represents the first step toward a MALT lymphoma |

| Udomsakdi-Auewarakul C Blood 2000 | Case series Period: NR | All malignancies: 130 Intermediate- to high-grade NHL: 98 Low-grade NHL 32 patients NHL classification: Working Formulation | 2/98 (2%) 1/32 (3.1%) | NR | NR | 2.(0-4.8) | No association between HCV infection and NHLs in this study from Thailand, where HCV infection is highly prevalent |

| Vajdic CM Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006 | Population-based case-control study Period: January 2000 and August 2001 | Total Lymphomas:694 -B-cell NHLs: 659 (95%) -T-cell NHLs: 28 (4%) -Undetermined: 7 (1%) NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | NHLs: 3/694 (0.4%) | Potential participants (both cases and controls) received a letter to inviting their participation in research about the development of NHL | 2/694 (0.3%) | 0.4 (0-0.9) | No strong evidence for an association between any infection and non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk in immunocompetent people, but increased risk between HCV infection and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in subjects with injecting drug use |

| Vallisa D Am J Med 1999 | Case-control study Period: 1990-1996 | B-cell-NHLs: 175 patients NHL classification: Working Formulation/Revised European American Lymphoma clasification | 65/175 (37.1%) | Subjects without lymphoma selected from: (1) inpatients (175) (2) outpatients (175) cared at Civil Hospital, Piacenza, subdivided into 2 groups | (1) 17/175 (10%) (2) 15/175 (9%) | 37.1 (30-44.3) | Possible HCV role as an etiologic agent in non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma |

| Varma S Hepatol Int 2011 | Case-control study Period: NR | B-NHLs: 57 patients High-grade disease (DLBCL): 44 (77.2%) Intermediate-disease (FC): 6 (10.5%) Low grade disease: (small lymphocytic): 7 (12.3%) NHL classification: World Health Organizations classification | 1/57 (1.7%) | Patients with non-hematological conditions admitted to Departments of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology, Dermatology, and Internal Medicine in the Hematology Clinic, Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh | 2/171 (1.2%) | 1.7 ( 0-5.1) | No significant association between HCV infection and NHL in Northern India |

| Veneri D Am J Hematol 2007 | Case series Period: January 1995 -December 2006 | 947 patients with lymphoproliferative disorders: DLBCL: 361 MM: 139 B-cell MZL: 62 HL: 103 B-CLL: 186 FL. 96 NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | 55/947 patients were HCV positive DLBCL: 27/361 (7.5%) MM: 1/139 (0.7%) B-cell MZL: 15/62 (24.2%) HL: 4/103 (3.9%) B-CLL: 4/186 (2.1%) FL: 4/96 (4.2%) | NR | NR | DLBCL: 7.5 (4.7-10.2) B-cell MZL: 24.2 (13.5-34.8) | Confirmed association between a subset of B-cell lymphomas and HCV infection |

| Yamac K Eur J Epidemiol 2000 | Case series Period: August 1996-June 1998, | All Lymphomas: 92 NHLs: 73 HL 19 NHL classification: Revised European American Lymphoma clasification | 1/92 (1.1%) | NR | NR | 1.1 (0-3.2) | No significant association between HCV and NHL in the study |

| Yenice N Turk J Gastroenterol 2003 | Case series with control group | All Lymphomas: 134 B cell NHLs: 84 HLs: 50 | B-cell NHLs: 6/84 (7.1%) HLs: 1/50 (2%) | Healthy blood donors | 1/100 (1%) | 7.1 (1.6-12.6) | HCV may play a role in the development of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but not in Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Yoshikawa M J Clin Gastroenterol 1997 | Case series with control group Periood: NR | All Lymphomas: 100 B-NHLs: 55 T-NHLs: 10 HL: 5 MM: 25 B-CLL: 2 MGUS: 3 NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-NHLs: 9/55 (16.4%) MM:5/25 (20%) MGUS: 1/3 (33.3%) | Patients with any cancer in digestive organs except liver enrolled at Nara Medical University | 1/25 (4%) | 16.4 (6.5-26.1) | High rates of HCV infection detected in B-NHL and MM |

| Yu SC Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2013 | Case series Period: 1988-2011 | All lymphomas: 74 patients: -B-cell lymphomas: 69 -T-cell lymphomas: 3 -Lymphoblastic Lymphoma: 1 -Unspecified high-grade lymphoma: 1 41/74 patients with serology for HCV infection NHL classification: World Health Organization’s classification | Patients with B-cell-NHL and with serology for HCV infection: 39 Patients with B-cell-NHL and HCV positive 10/39 (25.6%) | NR | NR | 25.6 (11.9-39.3) | High HCV sero-prevalence in patients with early-stage DLBCL suggests a role of HCV in the pathogenesis of primary DLBCL |

| Zucca E Haematologica 2000 | Case series Period: 1990 and 1995 | B-cell NHLs: 180 Anti-Helicobacter antibodies detected in 81/180 (45%) patients. NHL classification: REAL histological scheme | 17/180 (9.4%) Gastric lymphoma: 2 Non gastric lymphoma: 15 | A survey of 5424 subjects new blood donors from the same area tested between 1992 and 1997 (Swiss Red Cross Transfusional Medicine Service for Canton Ticino) | 49/5424 (0.9%) | 9.4 (5.1-13.7) | High prevalence of HCV infection detected in NHL lymphoma patients and associated with a shorter time to lymphoma progression. HCV infection not correlated with primary gastric presentation or with MALT-type histology |

| Zuckerman E Ann Intern Med 1997 | Controlled, cross-sectional study. Period: October 1994 and May 1996 | B-cell NHLs: 120 patients NHL classification: Working Formulation | B-cell NHLs 26/120 (22%) | (1) Patients with hematologic malignancies other than B-cell NHLs; (2) Patients without hematologic malignancies, attending the general medicine clinic at LAC-USC and with: systemic hypertension or ischemic heart disease: 69 diabetes mellitus: 35 primary hypothyroidism: 10 | 268 patients 7/154 (4.5%) (2) 6/114 (5%) | 21.7 (14.3-29) | Increased prevalence of HCV infection among patients from the United States with B-cell lymphoma, but uncertain generalizability to other populations, because of high number of patients, belonging to Hispanic ethnicity |

| Author/Journal/Publication year | Study design study period | CCA diagnosis | HCV positive colangiocarcinoma (n)/total colangiocarcinoma cases (n) | Total patients enrolled and control source | HCV positive controls (n)/controls (n) | Percentage of HCV-positive cases with 95%CI | Main conclusion |

| (A) | |||||||

| Abdel Wahab M 2007 | Case series Period: Januiary 1995-October 2004 | Histologic confirmation/CT/MRI/ERCP/PTD | 440 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma 238 anti-HCV positive patients 238/440 (54%) | NR | NR | 54.1 (49.4-58.7) | Liver cirrhosis and HCV may be risk factors For hilar cholangiocarcinoma in Egypt |

| Barusrux S Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2012 | Case series with control group Period: NR | Histologic confirmation | 8/295 (2.7%) | Total patients: 6120 Controls randomly selected from people in 4 provinces in Thailand, representing 4 geographically distinct areas and thus, populations in the North, North-east, South and Center of the country, respectively | 125/5825 (2.15%) HCV-Ab prevalence in Thailand ranging from 1.5% to 2.15%. Sunanchaikarn S, Theamboonlers A, Chongsrisawat V et al (2007). Seroepidemiology and genotypes of hepatitis C virus in Thailand. Asian Pac J Allergy, 25, 175-182 | 2.7 (0.8-4.5) | No significant association between CAA and HCV in northeast Thailand, with prevalence of HCV infection comparable among CCA and general population |

| Chantajitr S J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006 | Case series with control group Period: 2000-2004 | Histologic confirmation | HCC-CCA = 25 15 patients with test for anti- HCV 2/15 (13.3%) | Total patients: 75. 50 individuals, diagnosed with HCC at Ramathibodi Hospital | HCC = 50 32 patients with test for anti- HCV 1/32 (3.1%) | 13.3 (1.6-40.5) | No significant differences in presence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody (13% vs 3%) as etiologic risk factor between HCC-CC and HCC patients |

| Donato F Cancer Causes and control 2001 | Hospital-based case-control study Period: January 1, 1995-July 31, 2000 | Histologic confirmation | 6/24 (25%) | Total individuals: 848. Subjects unaffected by liver diseases or malignant neoplasms, admitted to the Department of Ophtalmology, Dermatology, Urology, Surgery, Cardiology, Internal Medicine in the two main Hospitals in Brescia, enrolled as controls | 50/824 (6%) | 25 (7.7-42.3) | HCV as possible risk factor for ICC in Western countries |

| El-Serag H Hepatology 2009 | Cohort study Period: October 1, 1988, and September 30, 2004 | Identification of PAC cases by means of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (157.0, 157.1, 157.2, 157.3, 157.8, 157.9) Identification of HCV infected subjects by means of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54 and V02.62) | HCV-infected cohort: 146394 patients ICC = 14 ECC = 15 | 718687 patients (146394 HCV-infected cohort, 572293 HCV-uninfected cohort) , ICC: 37 and ECC: 75 (14 ICC and 15 ECC in HCV infected patients, 23 ICC and 60 ECC in HCV uninfected subjects) | HCV-uninfected cohort: 572293 patients ICC = 23 ECC = 60 | ICC: 0.01 (0-0.15) ECC: 0.01 (0-0.15) | A more than twofold elevated risk of ICC in patients with HCV infection, absence of an association with ECC |

| Hai S Dig Surg 2005 | Case series with control group Period: January 1997 - December 2002 | Histologic confirmation | 19/50 (38%) | Total patients: 50 Subjects admitted to the Osaka City University Hospital or the Osaka City General Hospital | 31/50 (62%) | 38 (24.5-51.4) | Possibility to detect a small ICC or a hepatocellular carcinoma by means of a follow-up for patients with chronic HCV by imaging series at regular intervals |

| Hsing AW Int J Cancer 2008 | Population- based case-control study Period: June 1997 - May 2001, | Histologic confirmation or by means of ERCP | 3/234 (2%) with gallbladder cancers 2/134 (1.5%) with extrahepatic bile duct cancers 1/49 (2%) with Ampulla of Vater carcinomas | Total patients: 1696 Controls represented by biliary stone case patients and by healthy subjects without a history of cancer, randomly selected from all permanent residents listed in the Shanghai Resident Registry | 2/301 (0.7%) patients with gallbladder stones, 5/216 (2.3%) with bile duct stones and 15/762 (2%) healthy individuals | 1.5 (0-3.5) | Low prevalence of HCV infection in this population (2%), therefore limited ability to detect an association with biliary diseases |