Published online Dec 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12851

Peer-review started: March 19, 2015

First decision: April 23, 2015

Revised: May 16, 2015

Accepted: August 31, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: December 7, 2015

Processing time: 262 Days and 15 Hours

AIM: To elucidate the clinicopathological characteristics of clinically early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach and to clarify treatment precautions.

METHODS: A total of 683 patients with clinical early gastric cancer were enrolled in this retrospective study, 128 of whom had gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach (U group). All patients underwent a double contrast barium examination, endoscopy, and computed tomography (CT), and were diagnosed preoperatively based on the findings obtained. The clinicopathological features of these patients were compared with those of patients with gastric cancer in the middle- and lower-third stomach (ML group). We also compared clinicopathological factors between accurate-diagnosis and under-diagnosis groups in order to identify factors affecting the accuracy of a preoperative diagnosis of tumor depth.

RESULTS: Patients in the U group were older (P = 0.029), had a higher ratio of males to females (P = 0.015), and had more histologically differentiated tumors (P = 0.007) than patients in the ML group. A clinical under-diagnosis occurred in 57 out of 683 patients (8.3%), and was more frequent in the U group than in the ML group (16.4% vs 6.3%, P < 0.0001). Therefore, the rates of lymph node metastasis and lymphatic invasion were slightly higher in the U group than in the ML group (P = 0.071 and 0.082, respectively). An under-diagnosis was more frequent in histologically undifferentiated tumors (P = 0.094) and in those larger than 4 cm (P = 0.024). The median follow-up period after surgery was 56 mo (range, 1-186 mo). Overall, survival and disease-specific survival rates were significantly lower in the U group than in the ML group (P = 0.016 and 0.020, respectively). However, limited operation-related cancer recurrence was not detected in the U group in the present study.

CONCLUSION: Clinical early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach has distinguishable characteristics that increase the risk of a clinical under-diagnosis, especially in patients with larger or undifferentiated tumors.

Core tip: The clinicopathological features of patients with gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach (U group) were compared with those of patients with gastric cancer in the middle- and lower-third stomach (ML group). The rate of clinical under-diagnoses was significantly higher in the U group than in the ML group and more frequent in histologically undifferentiated tumors and in those larger than 4 cm.

- Citation: Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kosuga T, Konishi H, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Clinicopathological characteristics of clinical early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(45): 12851-12856

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i45/12851.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12851

Although the incidence of gastric cancer (GC) has recently plateaued, the frequency of GC in the upper-third stomach has increased[1-4]. In Asian countries, the detection of early GC in the upper-third stomach has also been increasing[2,3]. Less invasive treatment options, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy, have recently been performed on patients with early GC in the upper-third stomach in an attempt to preserve postoperative functions and improve the quality of life of these patients[5-9].

These recent findings prompted us to investigate the clinicopathological characteristics of early GC in the upper-third of the stomach. Treatment strategies are generally selected based on the preoperative findings of several examinations; therefore, we herein focused on patients with clinical early GC (T1) diagnosed preoperatively. In the present study, we retrospectively examined the clinicopathological characteristics of clinical early GC in the upper-third stomach and compared them with those in other regions. We also determined treatment precautions for patients with clinical early GC in the upper-third stomach.

A total of 1856 patients with GC were admitted to Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine between 1997 and 2013. Of these, 814 patients were diagnosed preoperatively with early GC (clinical T1) and underwent gastrectomy at our University Hospital. Patients with GC in the remnant stomach and with multiple GC detected previously were excluded from this study. A total of 683 patients with clinical T1 GC were enrolled in this retrospective study, 128 of whom had GC in the upper-third stomach. Of these, 59 patients underwent proximal gastrectomy. Lymph node dissection was performed based on the Guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association[10].

All patients underwent a double contrast barium examination, endoscopy, and computed tomography (CT) and were diagnosed preoperatively based on the findings obtained. Tumor depth was judged according to previously described criteria[11,12]. Briefly, the endoscopic criteria for mucosal cancer were a smooth surface protrusion, shallow and even depression, erosion with slight marginal elevation, or a flat or superficial spreading lesion. The criteria for submucosal cancer were an irregular or nodular surface with or without abnormal converging folds, such as clubbing and abrupt cutting, an irregular-based ulcer with marginal mucosal elevation, or marked depression with interrupted enlarged folds. The criteria for T2 or higher tumors were irregular based ulceration surrounded by a tumorous bank or marked depression when the tips of converging folds were elevated and merged. In CT examinations, non-visualized lesions and tumors confined to the inner or middle layers of the gastric wall were diagnosed as clinical T1 tumors, and full-thickness wall thickening with/without an irregular surface on the outer layer surrounding the tumors were diagnosed as clinical T2 or higher tumors[13-15]. Endoscopic ultrasonography was also performed in some patients, and the depth of tumor invasion was assessed based on the generally accepted 5-layer sonographic structure of the gastric wall, as recommended by the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC)/American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC). The clinicopathological features of these patients were reviewed retrospectively from hospital records and compared with those of patients with GC in the middle- and lower-third stomach. Helicobacter pylori infection was not necessarily examined in all cases in this study, therefore, we could not compare infection rates between the two groups. We also compared clinicopathological factors between accurate-diagnosis and under-diagnosis groups in order to identify the factors affecting the accuracy of a preoperative diagnosis of tumor depth. The macroscopic and microscopic classifications of GC were based on the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[10].

Continuous data were compared using the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The χ2 test was used to evaluate differences in the proportion of clinicopathological variables. Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, with the date of gastrectomy as the starting point. Only deaths from postoperative complications and GC recurrence were considered in the analysis of DSS. Differences in survival were examined by the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using Stat View 5.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). The significance of differences was accepted at P < 0.05.

The mean patient age was 63.4 years (range, 28-89 years), and the male: female ratio was 1.79:1. The median tumor size was 29.3 mm (range, 5-145 mm). The clinicopathological characteristics of patients and tumors in the upper-third stomach (U group) and middle- and lower-third of the stomach (ML group) are shown in Table 1. Patients in the U group were older, had a higher ratio of males to females, and had more histologically differentiated tumors than patients in the ML group. The number of pathological T2 or deeper tumors that had been clinically under-diagnosed was significantly higher in the U group than in the ML group. Therefore, the rates of lymph node metastasis and lymphatic invasion were slightly higher in the U group than in the ML group.

| Upper | Middle or Lower | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 66.1 | 62.8 | 0.029 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 94 | 344 | |

| Female | 34 | 211 | 0.015 |

| Macroscopic1 | |||

| Localized | 37 | 148 | |

| Diffuse | 91 | 405 | 0.620 |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 | |

| Histology | |||

| Diff.2 | 87 | 301 | |

| Undiff.3 | 41 | 247 | 0.0072 |

| Unknown | 0 | 7 | |

| Size (mm) | 30.9 | 28.9 | 0.340 |

| pT4 | |||

| T1 | 107 | 519 | |

| T2 | 21 | 35 | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 | |

| pN5 | |||

| Negative | 115 | 523 | |

| Positive | 13 | 32 | 0.071 |

| ly6 | |||

| Negative | 98 | 457 | |

| Positive | 27 | 82 | 0.082 |

| Unknown | 3 | 16 | |

| v7 | |||

| Negative | 110 | 497 | |

| Positive | 15 | 42 | 0.130 |

| Unknown | 3 | 16 |

A clinical under-diagnosis occurred in 57 out of 683 patients (8.3%) and was more frequent in the U group than in the ML group (16.4% vs 6.3%). The clinicopathological features of patients in the U group with an accurate-diagnosis and under-diagnosis are listed in Table 2. Although an under-diagnosis was more frequent in large and histologically undifferentiated tumors, the histological difference was not significant.

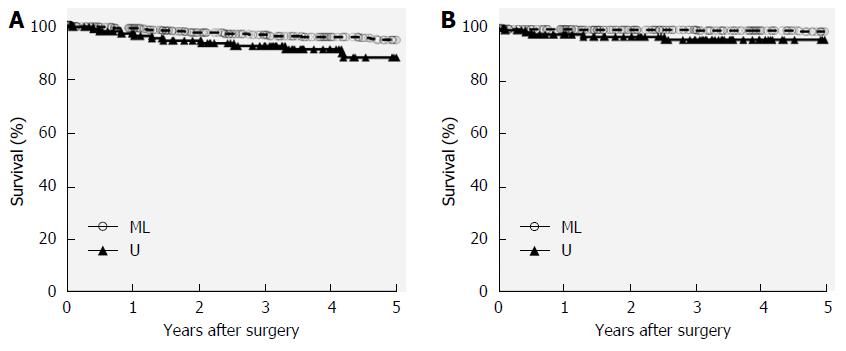

The median follow-up period after surgery was 56 mo (range, 1-186 mo). Thirty-four deaths, including 10 disease-related deaths, occurred during the follow-up period. Recurrence was noted in six patients (two and four patients in the U and ML groups, respectively), while four patients (three and one patients in U and ML groups, respectively) died of postoperative complications. Recurrence patterns were peritoneal dissemination in two patients, para-aortic lymph node metastasis in two, and hematogenous metastasis in two. OS and DSS rates were significantly lower in the U group than in the ML group (Figure 1). However, limited operation-related cancer recurrence was not detected in the U group in the present study.

The present study clearly showed that clinical T1 GC in the upper-third stomach has features that distinguish it from GC in other regions of the stomach, including older patients, a higher ratio of males to females, and more histologically differentiated tumors. Regarding the histological type, Kunisaki et al[16] also reported that patients with tumors in the upper-third stomach more frequently had differentiated tumors. However, the frequency of tumor differentiation may vary markedly between different countries, as previously reported[17].

The results of the present study revealed that clinical T1 GC in the U group was associated with a higher incidence of under-diagnosis of advanced GC (T2 or higher) in pathological examinations compared to the ML group. Since the extent of gastric resection and lymph node dissection is slightly narrower in such limited treatment options, accurate preoperative diagnoses are crucial for determining individualized treatment strategies. Early GC, which is confined to the mucosa and/or submucosa, has been diagnosed preoperatively based on the findings of upper barium contrast examinations and gastroscopy[11,12]. Endoscopic ultrasonography and multi-detector computed tomography have recently been utilized for more accurate diagnoses; however, preoperative under-diagnoses represent a frequent problem in the clinical staging of early GC[18-20]. The major drawback of this study was that endoscopic ultrasonography was not performed on all of the study patients. However, several recent studies indicated that endoscopic ultrasonography did not impact pretreatment staging of tumor depth, especially in patients with early GC[21-24]. The diagnostic accuracy of the depth of tumor invasion is considered to be affected by several factors[25,26]. Kim et al[26] reported that histologically undifferentiated-type tumors were associated with lower diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic assessments in preoperatively predicted tumor invasion, and the probability of a clinical under-diagnosis was significantly high. However, the number of histologically differentiated-type tumors was significantly higher in the U group than in the ML group in this study; therefore, the histological type was not involved in the under-diagnosis of clinical T1 in the U group. Other possible explanations for the predisposition toward an under-diagnosis are anatomy-related factors. Muscle bundles of the lamina muscularis mucosae are separated by wide spaces, are relatively sparse, and have a reticular arrangement in the cardia. In the more distal stomach, the spaces between the muscle bundles are narrower with a more dense reticular arrangement and a linear arrangement[27]. Therefore, superficial cancer may be vulnerable to infiltration to the muscle layer of the gastric wall. Another explanation is that fixation of the gastric wall to the diaphragm and retroperitoneum via a bare area of the stomach may reduce changes in the luminal face, which may play a role in the discrepancy observed between clinical and pathological diagnoses of tumor infiltration. Further investigations are needed in order to elucidate the exact reasons why tumors in the upper-third stomach are predisposed to clinical under-diagnosis.

Functional preservation operations, such as proximal gastrectomy and/or limited lymph node dissection, are now more likely to be performed on patients with clinically early GC in the upper-third stomach[6-8]. Previous studies demonstrated that proximal gastrectomy with regional lymphadenectomy was satisfactory for early GC in the upper-third stomach[6,8,28,29]; however, populations were collected based on pathological examinations in most of these studies. In these conservative operations, clinical under-diagnoses carry the potential risk of incomplete treatments. This study clearly demonstrated that a clinical under-diagnosis correlated with the presence of large and undifferentiated tumors; therefore, the potential risk of clinical underestimations needs to be considered in patients with these tumors.

The present study also investigated the long-term outcomes of clinical T1 GC in the upper-third stomach and compared them with those of patients who had GC in the more distal stomach. Patients with clinical T1 GC in the ML group had significantly better OS and DSS rates than those in the U group; however, the older mean age and higher rates of fatal complications in the U group appeared to be associated with decreased survival rates.

In conclusion, clinically early GC in the upper-third stomach has distinguishable characteristics from the more distal stomach, and the risk of a clinical under-diagnosis is greater in GC in the upper-third stomach, especially in patients with undifferentiated tumors or those larger than 4 cm. Particular attention is needed for the indication of limited operations in patients with those tumors.

Although the incidence of gastric cancer has recently plateaued, the frequency of gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach has increased. In Asian countries, the detection of early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach has also been increasing.

The authors herein investigated the clinicopathological characteristics of early gastric cancer in the upper-third of the stomach and also determined treatment precautions for patients with clinical early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach.

Treatment strategies are generally selected based on the preoperative findings of several examinations; therefore, the authors focused on patients with clinical early gastric cancer diagnosed preoperatively in this retrospective study.

Clinically early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach has distinguishable characteristics from the more distal stomach, and the risk of a clinical under-diagnosis is greater in upper-third stomach cancer, especially in patients with undifferentiated tumors or those larger than 4 cm.

Clinically early gastric cancer was diagnosed preoperatively based on the findings of a double contrast barium examination, endoscopy, and computed tomography.

The authors clearly demonstrated that clinically early gastric cancer in the upper-third stomach has distinguishable characteristics from the distal stomach that increase the risk for clinical under-diagnosis. Therefore, particular attention is needed for the indication of limited operations in patients with these tumors.

| 1. | Salvon-Harman JC, Cady B, Nikulasson S, Khettry U, Stone MD, Lavin P. Shifting proportions of gastric adenocarcinomas. Arch Surg. 1994;129:381-388; discussion 388-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Okabayashi T, Gotoda T, Kondo H, Inui T, Ono H, Saito D, Yoshida S, Sasako M, Shimoda T. Early carcinoma of the gastric cardia in Japan: is it different from that in the West? Cancer. 2000;89:2555-2559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, Jeong SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang HK. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg. 2011;98:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takeno S, Hashimoto T, Maki K, Shibata R, Shiwaku H, Yamana I, Yamashita R, Yamashita Y. Gastric cancer arising from the remnant stomach after distal gastrectomy: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13734-13740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Numata N, Oka S, Tanaka S, Kagemoto K, Sanomura Y, Yoshida S, Arihiro K, Shimamoto F, Chayama K. Risk factors and management of positive horizontal margin in early gastric cancer resected by en bloc endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:332-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Katai H, Morita S, Saka M, Taniguchi H, Fukagawa T. Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for suspected early cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2010;97:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hiki N, Nunobe S, Kubota T, Jiang X. Function-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2683-2692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Long-term outcomes of patients who underwent limited proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:141-145. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yoon JY, Shim CN, Chung SH, Park W, Chung H, Lee H, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC, Park JC. Impact of tumor location on clinical outcomes of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8631-8637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2956] [Article Influence: 197.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Sano T, Okuyama Y, Kobori O, Shimizu T, Morioka Y. Early gastric cancer. Endoscopic diagnosis of depth of invasion. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1340-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Endoscopic prediction of tumor invasion depth in early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:917-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Furukawa K, Miyahara R, Itoh A, Ohmiya N, Hirooka Y, Mori K, Goto H. Diagnosis of the invasion depth of gastric cancer using MDCT with virtual gastroscopy: comparison with staging with endoscopic ultrasound. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:867-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hasegawa S, Yoshikawa T, Shirai J, Fujikawa H, Cho H, Doiuchi T, Yoshida T, Sato T, Oshima T, Yukawa N. A prospective validation study to diagnose serosal invasion and nodal metastases of gastric cancer by multidetector-row CT. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2016-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mehmedović A, Mesihović R, Saray A, Vanis N. Gastric cancer staging: EUS and CT. Med Arch. 2014;68:34-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kunisaki C, Shimada H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono H, Akiyama H. Surgical outcome in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma in the upper third of the stomach. Surgery. 2005;137:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shim JH, Song KY, Jeon HM, Park CH, Jacks LM, Gonen M, Shah MA, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE. Is gastric cancer different in Korea and the United States? Impact of tumor location on prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2332-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Makino T, Fujiwara Y, Takiguchi S, Tsuboyama T, Kim T, Nushijima Y, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Nakajima K, Mori M. Preoperative T staging of gastric cancer by multi-detector row computed tomography. Surgery. 2011;149:672-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ganpathi IS, So JB, Ho KY. Endoscopic ultrasonography for gastric cancer: does it influence treatment? Surg Endosc. 2006;20:559-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shirahige A, Suzuki H, Oda I, Sekiguchi M, Mori G, Abe S, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Sekine S, Kushima R. Fatal submucosal invasive gastric adenosquamous carcinoma detected at surveillance after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4385-4390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and conventional endoscopy for prediction of depth of tumor invasion in early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2010;42:705-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Is endoscopic ultrasonography indispensable in patients with early gastric cancer prior to endoscopic resection? Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3177-3185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee HH, Lim CH, Park JM, Cho YK, Song KY, Jeon HM, Park CH. Low accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography for detailed T staging in gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hwang SW, Lee DH. Is endoscopic ultrasonography still the modality of choice in preoperative staging of gastric cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13775-13782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Akashi K, Yanai H, Nishikawa J, Satake M, Fukagawa Y, Okamoto T, Sakaida I. Ulcerous change decreases the accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography diagnosis for the invasive depth of early gastric cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim JH, Song KS, Youn YH, Lee YC, Cheon JH, Song SY, Chung JB. Clinicopathologic factors influence accurate endosonographic assessment for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:901-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Akashi Y, Noguchi T, Nagai K, Kawahara K, Shimada T. Cytoarchitecture of the lamina muscularis mucosae and distribution of the lymphatic vessels in the human stomach. Med Mol Morphol. 2011;44:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ohdaira H, Nimura H, Takahashi N, Mitsumori N, Kashiwagi H, Narimiya N, Yanaga K. The possibility of performing a limited resection and a lymphadenectomy for proximal gastric carcinoma based on sentinel node navigation. Surg Today. 2009;39:1026-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhao P, Xiao SM, Tang LC, Ding Z, Zhou X, Chen XD. Proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition and TGRY anastomosis for proximal gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8268-8273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Osawa S, Reshetnyak VI S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wang CH