Published online Nov 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12421

Peer-review started: May 7, 2015

First decision: June 2, 2015

Revised: June 17, 2015

Accepted: September 2, 2015

Article in press: September 3, 2015

Published online: November 21, 2015

Processing time: 195 Days and 20.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether long-term low-level hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA influences dynamic changes of the FIB-4 index in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients receiving entecavir (ETV) therapy with partial virological responses.

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed 231 nucleos(t)ide (NA) naïve CHB patients from our previous study (NCT01926288) who received continuous ETV or ETV maleate therapy for three years. The patients were divided into partial virological response (PVR) and complete virological response (CVR) groups according to serum HBV DNA levels at week 48. Seventy-six patients underwent biopsies at baseline and at 48 wk. The performance of the FIB-4 index and area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve for predicting fibrosis were determined for the patients undergoing biopsy. The primary objective of the study was to compare the cumulative probabilities of virological responses between the two groups during the treatment period. The secondary outcome was to observe dynamic changes of the FIB-4 index between CVR patients and PVR patients.

RESULTS: For hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients (n = 178), the cumulative probability of achieving undetectable levels at week 144 was 95% and 69% for CVR and PVR patients, respectively (P < 0.001). In the Cox proportional hazards model, a lower pretreatment serum HBV DNA level was an independent factor predicting maintained viral suppression. The cumulative probability of achieving undetectable levels of HBV DNA for HBeAg-negative patients (n = 53) did not differ between the two groups. The FIB-4 index efficiently identified fibrosis, with an AUROC of 0.80 (95%CI: 0.69-0.89). For HBeAg-positive patients, the FIB-4 index was higher in CVR patients than in PVR patients at baseline (1.89 ± 1.43 vs 1.18 ± 0.69, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the reduction of the FIB-4 index between the CVR and PVR groups from weeks 48 to 144 (-0.11 ± 0.47 vs -0.13 ± 0.49, P = 0.71). At week 144, the FIB-4 index levels were similar between the two groups (1.24 ± 0.87 vs 1.02 ± 0.73, P = 0.06). After multivariate logistic regression analysis, a lower baseline serum HBV DNA level was associated with improvement of liver fibrosis. In HBeAg-negative patients, the FIB-4 index did not differ between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: The cumulative probabilities of HBV DNA responses showed significant differences between CVR and PVR HBeAg-positive CHB patients undergoing entecavir treatment for 144 wk. However, long-term low-level HBV DNA did not deteriorate the FIB-4 index, which was used to evaluate liver fibrosis, at the end of three years.

Core tip: Long-term entecavir therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) can result in histological improvement and regression of fibrosis substantially. However, the relationship between the serum low level hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and fibrosis is unclear for CHB patients with partial virological response to entecavir. Our study found that although the cumulative probabilities of HBV DNA response showed a significant difference between hepatitis B e antigen-positive CHB patients with complete virological response and partial virological response to 144 wk of entecavir treatment, long-term low level HBV DNA did not deteriorate the FIB-4, which was used to evaluate liver fibrosis, by the end of three years.

- Citation: Li N, Xu JH, Yu M, Wang S, Si CW, Yu YY. Relationship between virological response and FIB-4 index in chronic hepatitis B patients with entecavir therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(43): 12421-12429

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i43/12421.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12421

In the Asia-Pacific region, approximately 75 million people die annually from end stage liver diseases caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV)[1]. Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are generally the inevitable and irreversible stages of end stage liver diseases. A large prospective cohort study (REVEAL-HBV study) in Taiwan and several case-control studies have revealed that progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients is closely related to the level of circulating virus[2,3]. In addition, improvement in histological grade is strongly associated with a decrease in serum HBV DNA levels[4,5]. Therefore, HBV replication can be suppressed in a sustained manner, defined as a reduction of serum HBV DNA to undetectable levels, which is the ultimate goal for CHB treatment.

Entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) have been suggested as the first-line nucleos(t)ide (NA) therapy for CHB. TDF has not been widely used in China because it only became available for CHB treatment in 2014. Thus, ETV is the preferred first-line agent in patients with NA-naive CHB[6]. Given that early HBV DNA responses to therapy can strongly predict the results of long-term virological responses, modification of the treatment schedule is widely recommended for patients with partial virological response (PVR)[7]. However, in contrast to the traditional guidelines, it has been suggested that it is unnecessary to modify antiviral therapy (ETV) in PVR patients, especially if the viral load at week 48 is low[8]. Long-term entecavir therapy for patients with CHB can cause histological improvement and regression of fibrosis[9,10]. However, the relationship between low serum levels of HBV DNA and fibrosis is unclear for CHB patients with PVR to ETV.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard in assessing liver fibrosis in CHB patients[11,12]. However, liver biopsies have limitations of invasiveness, high expense and high sampling error. Thus, observing dynamic changes in liver fibrosis is restricted. Non-invasive tests for the evaluation of liver fibrosis have the advantages of simplicity and repeatability. Although non-invasive tests as an alternative to liver biopsies are restricted either by the cost of the device or by the need for a specific laboratory examination, some of the non-invasive tests have not been proven for the evaluation of fibrosis in CHB[11]. The FIB-4 index, a simple non-invasive test, combines age, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and platelet (PLT) to identify HBV-related fibrosis with a moderate sensitivity[13]. Therefore, both liver biopsies and the FIB-4 index were used to assess liver fibrosis in this study.

The goal of this study was to assess whether persistence of low-level viral replication influences the regression of liver fibrosis in CHB patients with PVR as determined by the FIB-4 index.

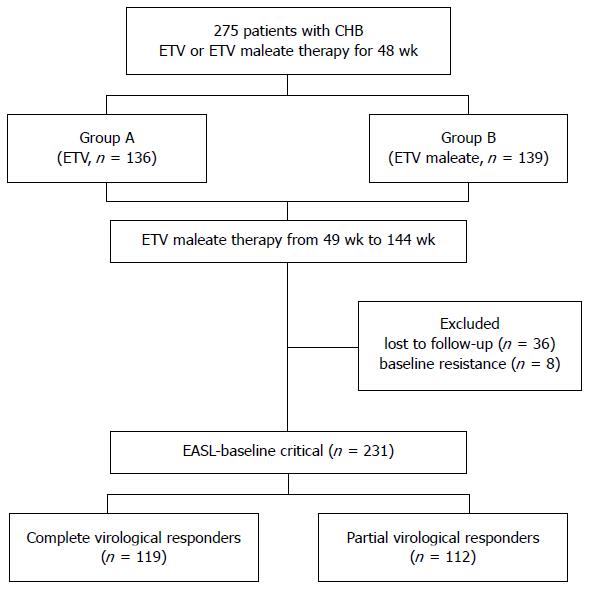

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data for 275 CHB patients from our previous study from 2008 to 2014 (NCT01926288), which was a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled, multi-center study[14,15]. All patients were hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive for at least 6 mo and NA-naive prior to ETV treatment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 48 wk of treatment with 0.5 mg/d ETV (group A; n = 136) or 0.5 mg/d ETV maleate (group B; n = 139). After 48 wk of treatment, ETV maleate showed similar efficacy and safety profiles as entecavir. Therefore, all patients were given ETV maleate treatment after 48 wk. Forty-four patients were excluded from the study due to loss to follow-up (n = 36) and baseline resistance (n = 8). A total of 231 patients were eligible, and the ETV maleate treatment was continued for three years (Figure 1). According to the European guideline, the 231 patients were divided into PVR and complete virological response (CVR) groups. The definition of CVR to entecavir was HBV DNA being undetectable at week 48, and PVR to entecavir was defined as a > 1 log decline in HBV DNA from baseline but a detectable viral load at week 48[6].

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University First Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from each patient enrolled in the study. All patients undergoing liver biopsy signed an informed medical consent form.

All patients were prospectively monitored every 3 mo. Serum ALT, AST and PLT levels were tested locally with standard laboratory procedures. Serologic marker analyses, including HBsAg, anti-HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and anti-HBe, were measured by commercially available enzyme immunoassays (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Serum HBV DNA was determined by a commercially available real-time polymerase chain reaction assay (Cobas Ampliprep/Cobas Taqman) with a lower limit of detection of 20 IU/mL.

Percutaneous liver biopsies were performed on 76 of the 231 participants (33%) at baseline and at 48 wk. All liver biopsies were obtained by the local doctor, and liver histology was determined via the Ishak score as assessed by two experienced pathologists who were blinded to the patient details. All patients were grouped into two fibrosis stages: mild and moderate (Ishak fibrosis scores 0-3) and advanced (Ishak fibrosis scores 4-6)[16].

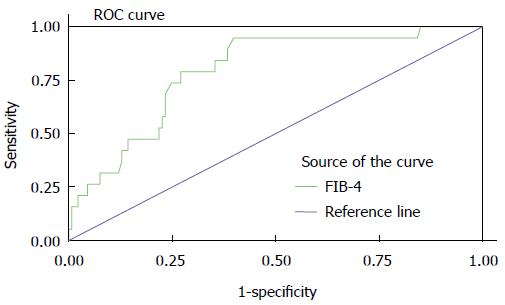

FIB-4 index was determined according to the following published formula[17,18]: FIB-4 index = Age (years) × AST (IU/L)/platelet count (109/L) × ALT (IU/L)1/2. The values of the FIB-4 index were compared with the Ishak fibrosis scores. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the FIB-4 index to assess liver fibrosis was then developed in 152 person-times under biopsy. Using the previously published cut-off for the FIB-4 index, patients were placed into two classes (FIB-4 index ≤ 1.45 and FIB-4 index >1.45)[19].

The primary objective was to compare the cumulative probabilities of the virological responses in the two groups during the on-treatment follow-up period. The secondary objective was to compare dynamic changes of the FIB-4 index between CVR and PVR patients.

The cumulative probabilities of the virological responses (HBV DNA < 20 IU/mL) were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Cox regression analysis was used to determine which of the following baseline factors were associated with complete virological responses to ETV: age, sex, HBeAg status, viral load, ALT/AST level and FIB-4 index. ROC curve analysis was used to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the FIB-4 index in predicting the extent of fibrosis (Ishak scoring system). All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analyses.

The baseline characteristics and virological responses of the study population treated with ETV or ETV maleate are shown in Table 1. Of the 231 subjects in this study, 74.4% were male, and the mean age was 32.5 years. The mean HBV DNA level was 7.36 log10 IU/mL, the mean ALT level was 152.0 IU/L, and 77.0% of patients were HBeAg-positive. At week 48, there were no significant differences in HBV DNA level, normalization of ALT and HBeAg loss among HBeAg-positive patients between groups A and B. Due to the efficacy of ETV maleate, all patients were treated with ETV maleate from week 48.

| All patients | Group A | Group B | P value | |

| (n = 231) | (n = 112) | (n = 119) | ||

| Age (yr) | 32.5 ± 10.1 | 32.6 ± 9.78 | 32.5 ± 10.4 | 0.96 |

| Male (%) | 172 (74.4) | 83 (74.1) | 89 (74.8) | 0.99 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 113 ± 115 | 113 ± 117 | 113 ± 116 | 0.75 |

| AST (IU/L) | 64 ± 74 | 65 ± 75 | 62 ± 67 | 0.74 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 167.7 ± 57.3 | 170.0 ± 53.9 | 165.7 ± 60.5 | 0.56 |

| HBeAg-positive (%) | 178 (77.0) | 89 (79.5) | 89 (74.8) | 0.43 |

| HBV DNA at baseline | 7.36 ± 1.20 | 7.38 ± 1.15 | 7.35 ± 1.25 | 0.11 |

| (log10 IU/mL) | ||||

| HBV DNA at week | 1.81 ± 0.85 | 1.74 ± 0.83 | 1.88 ± 0.87 | 0.08 |

| 48 (log10 IU/mL) | ||||

| HBV DNA-negative | 111 (48.1) | 54 (48.2) | 56 (47.1) | 0.86 |

| (< 20 IU/mL) | ||||

| HBeAg seroconversion | 19 (8.2) | 10 (8.9) | 9 (7.6) | 0.71 |

| in HBeAg-positive patients | ||||

| ALT normalization | 176 (76.2) | 85 (75.9) | 91 (76.5) | 0.91 |

The clinical characteristics of patients with CVR and PVR are shown in Table 2. CVR patients were older compared with PVR patients (P < 0.001). Baseline serum HBV DNA levels (P < 0.001) and the proportion of HBeAg-positive patients (P < 0.001) were higher in PVR than in CVR patients. Pretreatment serum AST levels (P = 0.002) and FIB-4 index scores (P < 0.001) were higher in CVR patients than in PVR patients. After adjusting for covariates by multivariate logistic regression analysis, pretreatment serum HBV DNA levels and the proportion of HBeAg-positive patients still showed significant differences between the two groups. All other baseline characteristics did not differ between the groups.

| Virological response at week 48 | |||

| CVR | PVR | P value | |

| (n = 119) | (n = 112) | ||

| Age (yr) | 34.9 ± 10.9 | 30.2 ± 8.8 | < 0.0011 |

| Male (%) | 78 (70.3) | 94 (80.8) | 0.16 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 120 ± 130 | 108 ± 88 | 0.05 |

| AST (IU/L) | 78 ± 87 | 57 ± 41 | 0.0011 |

| PLT (× 109/L ) | 160 ± 55 | 175 ± 58 | 0.07 |

| HBeAg-positive (%) | 71 (64) | 107 (89) | < 0.0012 |

| HBV DNA | 6.88 ± 1.23 | 7.78 ± 0.92 | < 0.0012 |

| (log10 IU/mL) | |||

| Group A (%) | 55 (50) | 57 (47.5) | 0.75 |

| Genotype | 0.77 | ||

| B | 56 (51.4) | 53 (48.6) | |

| C | 65 (58.5) | 57 (47.5) | |

| FIB-4 index | 2.01 ± 1.43 | 1.21 ± 0.76 | 0.0031 |

The clinical characteristics of the 178 HBeAg-positive and 53 HBeAg-negative patients are shown in Table 3. In HBeAg-positive patients, there were more males in the PVR group than in the CVR group (P = 0.04). Baseline serum HBV DNA levels were lower in CVR patients than in PVR patients (7.26 ± 1.05 vs 7.92 ± 0.89, P < 0.001). In the CVR group, pretreatment serum AST and the FIB-4 index were higher than those in PVR patients (P < 0.01). However, after adjusting for significant covariates in the univariate analysis, these differences were no longer significant. There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of HBeAg-negative patients between groups.

| HBeAg-positive (n = 178) | HBeAg-negative (n = 53) | |||||

| CVR | PVR | P value | CVR | PVR | P value | |

| (n = 71) | (n = 107) | (n = 48) | (n = 5) | |||

| Age (yr) | 32.1 ± 9.9 | 29.7 ± 8.7 | 0.09 | 39.2 ± 10.3 | 35.2 ± 11.7 | 0.22 |

| Male n (%) | 49 (69) | 88 (82) | 0.041 | 29 (72) | 6 (46) | 0.08 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 121 ± 143 | 107 ± 90 | 0.108 | 118 ± 124 | 120 ± 74 | 0.89 |

| AST (IU/L) | 82 ± 88 | 56 ± 42 | 0.0021 | 73 ± 76 | 67 ± 92 | 0.75 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 158 ± 53 | 175 ± 58 | 0.05 | 163 ± 58 | 181 ± 75 | 0.97 |

| HBV DNA | 7.26 ± 1.05 | 7.92 ± 0.89 | 0.0011 | 6.32 ± 1.29 | 6.62 ± 0.87 | 0.15 |

| (log10 IU/mL) | ||||||

| Group A, n (%) | 39 (55) | 51 (47) | 0.34 | 19 (39) | 4 (80) | 0.08 |

| FIB-4 index | 1.89 ± 1.43 | 1.18 ± 0.69 | 0.0011 | 2.17 ± 1.44 | 1.92 ± 1.67 | 0.84 |

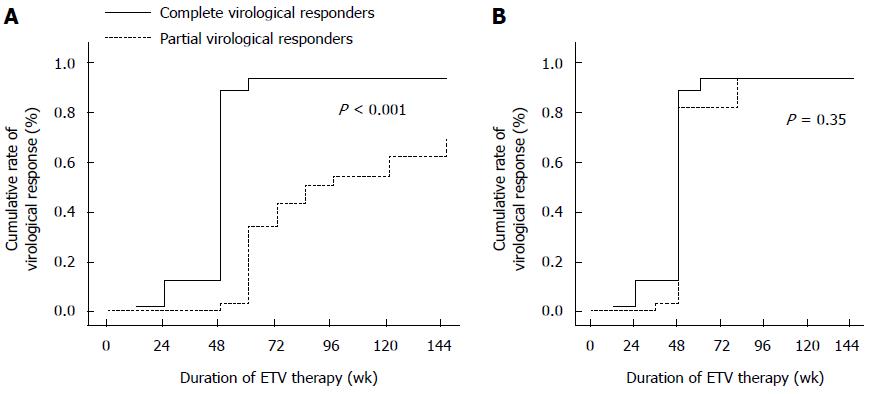

The overall cumulative probabilities of maintained viral suppression at years 1, 2 and 3 were 48.1%, 70.6% and 81.3%, respectively. In HBeAg-positive patients (n = 178), the cumulative probabilities of achieving undetectable levels at weeks 48, 96 and 144 were 42%, 67% and 80%, respectively. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis for HBeAg-positive patients, there was a significant difference in the cumulative probability of achieving undetectable levels at week 144 between the CVR and PVR groups (95% vs 69%, P < 0.001; Figure 2A). In the Cox proportional hazards model, lower pretreatment and week 48 serum HBV DNA levels were the independent factors predicting maintained viral suppression (Table 4).

| Maintained viral suppression at week 144 | |||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.008 | 0.98-1.04 | 0.54 |

| Sex | 0.927 | 0.694-1.325 | 0.68 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 1.000 | 0.997-1.004 | 0.81 |

| AST (IU/L) | 1.001 | 0.994-1.000 | 0.77 |

| PLT (× 109/L ) | 0.998 | 0.994-1.000 | 0.40 |

| HBeAg-positive | 1.326 | 0.918-1.916 | 0.13 |

| Baseline HBV DNA | 0.781 | 0.678-0.900 | < 0.001 |

| (log10 IU/mL) | |||

| HBV DNA at week 48 | 0.768 | 0.694-0.993 | < 0.001 |

| (log10 IU/mL) | |||

| FIB-4 index | 0.737 | 0.452-1.199 | 0.22 |

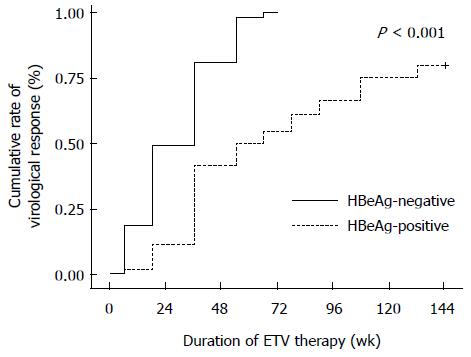

The cumulative probabilities of HBV DNA responses in HBeAg-negative patients (n = 53) at weeks 48, 96 and 144 were 87%, 100% and 100%, respectively (Figure 3). Conversely, the cumulative probabilities of achieving undetectable levels of HBV DNA at week 144 for HBeAg-negative patients were similar between the two groups (Figure 2B).

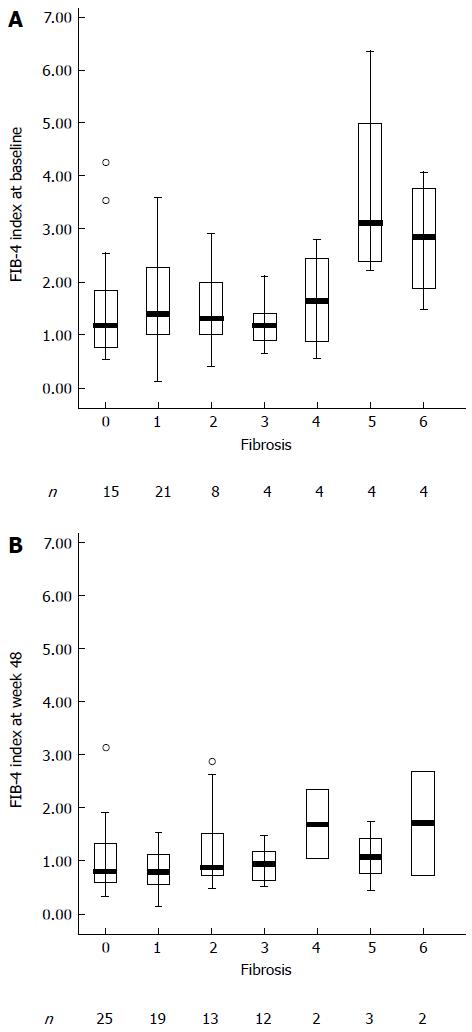

In patients with significant fibrosis (Ishak scores 4-6), the FIB-4 index was significantly higher when compared with patients with no/mild fibrosis (Ishak scores 0-3) (Figure 4A). After 48 wk of ETV therapy, the FIB-4 index was reduced significantly (Figure 4B). The FIB-4 index did not show a significant difference among the Ishak scores 0-3 (P = 0.76). There was also no significant difference among the Ishak scores 4-6 (P = 0.17). The FIB-4 index showed a significant difference between Ishak scores 0-3 and Ishak scores 4-6 (P < 0.001). The FIB-4 index efficiently identified fibrosis, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.80 (95%CI: 0.69-0.89; Figure 5). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for the FIB-4 index were 0.95, 0.60, 0.25 and 0.64, respectively.

Compared with PVR patients, the FIB-4 index was higher for CVR patients at baseline in HBeAg-positive patients (1.18 ± 0.69 vs 1.89 ± 1.43, P < 0.001). The changes in the FIB-4 index were higher in CVR patients than in PVR patients from baseline to week 144 (0.64 ± 1.25 vs 0.15 ± 0.72, P = 0.004). From week 48 to 144, the FIB-4 index was not significantly reduced between the CVR and PVR groups (-0.11 ± 0.47 vs -0.13 ± 0.49, P = 0.71). At week 144, the levels of the FIB-4 index were similar between the two groups (1.24 ± 0.87 vs 1.02 ± 0.73, P = 0.06). After the multivariate logistic regression analysis, lower baseline serum HBV DNA level was associated with improvement of liver fibrosis. In HBeAg-negative patients, dynamic changes of the FIB-4 index did not differ between the two groups (Table 5).

| HBeAg-positive (n = 178) | HBeAg-negative (n = 53) | |||||

| CVR (n = 71) | PVR (n value = 107) | P value | CVR (n = 48) | PVR (n = 5) | P value | |

| 0 wk | 1.89 ± 1.43 | 1.18 ± 0.69 | < 0.001 | 2.17 ± 1.44 | 1.92 ± 1.66 | 0.71 |

| 48wk | 1.20 ± 0.81 | 0.94 ± 0.57 | 0.007 | 1.50 ± 0.89 | 1.52 ± 0.82 | 0.79 |

| 144 wk | 1.24 ± 0.87 | 1.02 ± 0.73 | 0.06 | 1.49 ± 0.90 | 1.12 ± 0.44 | 0.37 |

| 48-144 wk | -0.11 ± 0.47 | -0.13 ± 0.49 | 0.71 | -0.02 ± 0.34 | -0.07 ± 0.38 | 0.44 |

| 0-144 wk | 0.64 ± 1.25 | 0.15 ± 0.72 | 0.004 | 0.68 ± 0.95 | 0.81 ± 1.25 | 0.79 |

According to the level of HBV DNA at week 144, the 178 HBeAg-positive patients were divided into two groups (groups a and b). The patients who achieved undetectable level of HBV DNA was classified as group a (n = 120), the other patients was defined as group b (n = 58). At baseline, the FIB-4 index did not show a significant difference between groups a and b (1.56 ± 1.14 vs 1.27 ± 0.99, P = 0.11). The dynamic changes of FIB-4 index did not differ from baseline to week 144 between groups a and b (0.44 ± 0.99 vs 0.17 ± 0.98, P = 0.09). At week 144, the FIB-4 index also did not show a significant difference between groups a and b (1.12 ± 0.81 vs 1.10 ± 0.78, P = 0.89) (Table 6).

| Group a (n = 120) | Group b (n = 58) | P value | |

| 0 wk | 1.56 ± 1.14 | 1.27 ± 0.99 | 0.11 |

| 144 wk | 1.12 ± 0.81 | 1.10 ± 0.78 | 0.89 |

| 0-144 wk | 0.44 ± 0.99 | 0.17 ± 0.98 | 0.09 |

Even with prolonged ETV monotherapy for 3 years, we found that the cumulative response rates of HBV DNA in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients at week 144 were significantly lower for PVR patients to ETV than for CVR patients. Lower pretreatment serum HBV DNA levels were an independent factor predicting maintained viral suppression and contributed to a greater FIB-4 index reduction by entecavir therapy. Although the degree of fibrosis regression was higher in the CVR group than in the PVR group, the mean values of the FIB-4 index were similar and less than 1.45 in the two groups by the end of therapy.

A study in a large cohort of NA-naive CHB patients treated with ETV monotherapy has shown that long-term ETV therapy leads to a VR for patients with both primary response and nonresponse according to EASL and AASLD[20]. The definitions of primary response or nonresponse for the cohort study were based on data from studies of less potent drugs with a higher risk of antiviral resistance[21,22]. The study suggested that changing the therapeutic scheme in patients with a primary nonresponse should depend on drug differences in antiviral potency and resistance risk. Wong et al[23] reported that CVRs to ETV at week 48 (HBV DNA < 20 IU/mL) could predict the probability of maintained virological suppression at 3 years. Therefore, patients were stratified on the basis of serum HBV DNA levels at week 48.

Zoutendijk et al[8] found that HBV DNA was reduced to undetectable levels (HBV DNA < 80 IU/mL) in the majority of patients with partial VR (84%) after prolonged treatment with ETV. However, our study found that only 58 of the 112 PVR patients to ETV (52%) achieved undetectable HBV DNA levels (HBV DNA < 20 IU/mL) at 144 wk. The differences were likely due to the proportion of HBeAg-positive patients, which was higher in our patients than the above study (95.5% vs 77.7%). For HBeAg-positive patients, the cumulative probability of achieving VR at week 144 was lower than in HBeAg-negative patients (80% vs 100%).

Our study found that the FIB-4 index efficiently identified fibrosis, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.80. In addition, the Ishak score and FIB-4 index were similar in evaluating liver fibrosis at baseline and at week 48. Therefore, the FIB-4 index was identified as a non-invasive method to assess fibrosis in our study. The level of the FIB-4 index at baseline and the changes of the FIB-4 index from baseline to week 144 for HBeAg-positive patients were significantly higher in CVR patients than in PVR patients. Compared with PVR patients, especially for HBeAg-positive patients, CVR patients were characterized by older age, elevated AST, and lower HBV DNA levels. This indicates that patients with higher FIB-4 index values and lower HBV DNA levels at baseline could have better improvement in the FIB-4 index after receiving ETV therapy[24]. Xie et al[25] also showed that serum ALT, serum HBV DNA levels and age were associated with significant fibrosis in HBeAg-positive patients. Liver fibrosis progression and viral load suppression are caused by T cell-mediated immune responses[26]. If the immune response induced by T cells is strong, naïve chronic hepatitis B patients will respond better to ETV therapy. Because of nearly half of PVR patients (45%, n = 49) whose HBV DNA levels were undetectable at week 144 in the HBeAg-positive group, it is necessary to evaluate the dynamic changes of FIB-4 index according to the level of HBV DNA at week 144. The dynamic changes of FIB-4 index did not show a significant difference. Because of the low level of HBV DNA at baseline in HBeAg-negative patients, the cumulative probability of maintained viral suppression and dynamic changes of the FIB-4 index were similar between CVR patients and PVR patients.

There are several limitations in our study. The main limitations of this study were retrospective nature, the short duration of observation during entecavir treatment and too small sample of patients who underwent liver biopsies. Thus, long-term follow-up assessments are ongoing. Further studies with larger liver biopsies are necessary to remedy these shortcomings and to elucidate the long-term outcomes of ETV treatment. In addition, the study did not observe the dynamic changes of liver inflammation in chronic hepatitis B patients with entecavir therapy and the changes of FIB-4 index have not been reported in the proportion of immunotolerant and immunoactive patients. In the later study, we will observe the changes of FIB-4 index and liver inflammation in the immunotolerant and immunoactive patients infected with HBV.

In conclusion, although the cumulative probabilities of HBV DNA responses showed significant differences between CVR and PVR patients after treatment with entecavir for 144 wk, the FIB-4 index, which was used to evaluate liver fibrosis, did not differ until the end of the observation period. Entecavir therapy resulted in the reversal of fibrosis in CHB patients, especially in HBeAg-positive patients with CVR and HBeAg-negative patients. Long-term low-level HBV DNA in PVR patients did not deteriorate the FIB-4 index at the end of 3 years.

The relationship between low serum levels of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and fibrosis is unclear for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with partial virological response to entecavir (ETV).

Non-invasive tests for the evaluation of liver fibrosis have the advantages of simplicity and repeatability. Although non-invasive tests as an alternative to liver biopsies are restricted either by the cost of the device (FibroScan) or by the need for a specific laboratory examination (FibroTest), the FIB-4 index which is a simple non-invasive test has the ability to identify HBV-related fibrosis with a moderate sensitivity.

The cumulative probabilities of HBV DNA responses showed significant differences between the CVR and PVR group in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive CHB patients undergoing entecavir treatment for 144 wk. Non-invasive long-term low-level HBV DNA did not deteriorate the FIB-4 index, which was used to evaluate liver fibrosis of CHB patients. Older age and lower HBV DNA levels are associated with FIB-4 index in HBeAg-positive CHB patients.

FIB-4 index can be used to evaluate the dynamic changes of liver fibrosis in CHB patients receiving ETV therapy.

FIB-4 index was determined according to the following published formula: FIB-4 index = Age (years) × AST (IU/L)/PLT (109/L) × ALT (IU/L)1/2.

The study reported the easily available FIB-4 index as a marker of hepatic fibrosis in patients on long-term entecavir therapy for chronic HBV hepatitis. The paper confirmed the effectiveness of entecavir therapy for chronic HBV hepatitis and the improvement in liver histology. The improvement in the Ishak score is reflected by a decrease in the FIB-4 score.

| 1. | Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384:2053-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1004] [Cited by in RCA: 1202] [Article Influence: 100.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vardar R, Gunsar F, Sertoz R, Ozacar T, Nart D, Barbet FY, Karasu Z, Ersoz G, Akarca US. The relationship between HBV-DNA level and histology in patients with naive chronic HBV infection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:908-912. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Shao J, Wei L, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang LF, Li J, Dong JQ. Relationship between hepatitis B virus DNA levels and liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2104-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu B, Lin L, Xu G, Zhuang Y, Guo Q, Liu Y, Wang H, Zhou X, Wu S, Bao S. Long-term lamivudine treatment achieves regression of advanced liver fibrosis/cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:372-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tong MJ, Kowdley KV, Pan C, Hu KQ, Chang TT, Han KH, Yoon SK, Goodman ZD, Beebe S, Iloeje U. Improvement in liver histology among Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B after long-term treatment with entecavir. Liver Int. 2013;33:650-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1156] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Keeffe EB, Zeuzem S, Koff RS, Dieterich DT, Esteban-Mur R, Gane EJ, Jacobson IM, Lim SG, Naoumov N, Marcellin P. Report of an international workshop: Roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:890-897. |

| 8. | Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Brown A, Zoulim F, Mutimer D, Deterding K, Petersen J, Hofmann WP, Buti M, Santantonio T. Entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B: adaptation is not needed for the majority of naïve patients with a partial virological response. Hepatology. 2011;54:443-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 788] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schiff ER, Lee SS, Chao YC, Kew Yoon S, Bessone F, Wu SS, Kryczka W, Lurie Y, Gadano A, Kitis G. Long-term treatment with entecavir induces reversal of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:274-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Enomoto M, Morikawa H, Tamori A, Kawada N. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12031-12038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wan R, Liu H, Wang X, Wan G, Wang X, Zhou G, Jiang Y, Sun F, Yang Z. Noninvasive predictive models of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:961-971. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Xiao G, Yang J, Yan L. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and fibrosis-4 index for detecting liver fibrosis in adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015;61:292-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu JH, Yu YY, Si CW, Zeng Z, Zhang DZ. [A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled, multicenter study of entecavir maleate versus entecavir for treatment of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: results at week 48]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2012;20:512-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xu JH, Yu YY, Si CW, Zeng Z, Li J, Mao Q, Zhang DZ, Tang H, Sheng JF, Chen XY. [Analysis of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled, multicenter study confirmed the similar therapeutic efficacies of entecavir maleate and entecavir for treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2013;21:881-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696-699. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, Fontaine H, Pol S. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1661] [Article Influence: 87.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3806] [Article Influence: 190.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang H, Xue L, Yan R, Zhou Y, Wang MS, Cheng MJ, Huang HJ. Comparison of FIB-4 and APRI in Chinese HBV-infected patients with persistently normal ALT and mildly elevated ALT. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:e3-e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang YJ, Shim JH, Kim KM, Lim YS, Lee HC. Assessment of current criteria for primary nonresponse in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving entecavir therapy. Hepatology. 2014;59:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yuen MF, Fong DY, Wong DK, Yuen JC, Fung J, Lai CL. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels at week 4 of lamivudine treatment predict the 5-year ideal response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1695-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Zeuzem S, Gane E, Liaw YF, Lim SG, DiBisceglie A, Buti M, Chutaputti A, Rasenack J, Hou J, O’Brien C. Baseline characteristics and early on-treatment response predict the outcomes of 2 years of telbivudine treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;51:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Wong GL, Wong VW, Chan HY, Tse PC, Wong J, Chim AM, Yiu KK, Chu SH, Chan HL. Undetectable HBV DNA at month 12 of entecavir treatment predicts maintained viral suppression and HBeAg-seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B patients at 3 years. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1326-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kuo YH, Lu SN, Chen CH, Chang KC, Hung CH, Tai WC, Tsai MC, Tseng PL, Hu TH, Wang JH. The changes of liver stiffness and its associated factors for chronic hepatitis B patients with entecavir therapy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xie Q, Hu X, Zhang Y, Jiang X, Li X, Li J. Decreasing hepatitis B viral load is associated with a risk of significant liver fibrosis in hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2014;86:1828-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang PL, Althage A, Chung J, Maier H, Wieland S, Isogawa M, Chisari FV. Immune effectors required for hepatitis B virus clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:798-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Panduro A, Stalke P S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM