Published online Nov 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12403

Peer-review started: December 30, 2015

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: March 29, 2015

Accepted: June 9, 2015

Article in press: June 10, 2015

Published online: November 21, 2015

Processing time: 323 Days and 6.4 Hours

AIM: To report the outcome of surgery in patients with (pre)malignant conditions of celiac disease (CD) and the impact on survival.

METHODS: A total of 40 patients with (pre)malignant conditions of CD, ulcerative jejunitis (n = 5) and enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) (n = 35), who underwent surgery between 2002 and 2013 were retrospectively evaluated. Data on indications, operative procedure, post-operative morbidity and mortality, adjuvant therapy and overall survival (OS) were collected. Eleven patients with EATL who underwent chemotherapy without resection were included as a control group for survival analysis. Patients were followed-up every three months during the first year and at 6-mo intervals thereafter.

RESULTS: Mean age at resection was 62 years. The majority of patients (63%) underwent elective laparotomy. Functional stenosis (n = 13) and perforation (n = 12) were the major indications for surgery. In 70% of patients radical resection was performed. Early postoperative complications, mainly due to leakage or sepsis, occurred in 14/40 (35%) of patients. Eight patients required reoperation. More patients who underwent resection in the acute setting (n = 3, 20%) died compared to patients treated in the elective setting. With a median follow-up of 20 mo, seven patients (18%) required reoperation due to long-term complications. Significantly more patients who underwent acute surgery could not be treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients who first underwent surgical resection showed significantly better OS than patients who received chemotherapy without resection.

CONCLUSION: Although the complication rate is high, the preferred first step of treatment in (pre)malignant CD consists of local resection as early as possible to improve survival.

Core tip: A small percentage of patients with celiac disease develop (pre)malignant conditions including enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma. No standardized treatment has been established. Surgery is indicated to relieve clinical symptoms or prevent perforation during chemotherapy. Although the frequency of early- and late post-operative complications is high, local resection is the preferred first step of treatment. Resection is preferred as early as possible after diagnosis since treatment-related mortality seems to rise in the acute setting. Early diagnosis is of utmost importance as elective surgical resection might lower the risk of post-operative mortality and improve overall survival.

- Citation: van de Water JM, Nijeboer P, de Baaij LR, Zegers J, Bouma G, Visser OJ, van der Peet DL, Mulder CJ, Meijerink WJ. Surgery in (pre)malignant celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(43): 12403-12409

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i43/12403.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12403

Celiac disease (CD) is a common immune-mediated enteropathy affecting approximately 0.6% of individuals in the Western population[1]. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is a very rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma that develops in an estimated 0.04% of adult-onset CD patients[2]. In approximately 30%-50%[3,4] this is preceded by a state of refractoriness to a gluten-free diet, referred to as refractory celiac disease type II (RCDII). This disease state is characterized by the occurrence of duodenal T cells with an aberrant phenotype and RCDII is now considered a low-grade lymphoma. Such low-grade lymphomas may also sporadically manifest as ulcerative jejunitis (UJ) with deep ulcerations and stenosis[5].

Due to the rarity of UJ and EATL, no standardized therapeutic regimens have been established for these entities. In general, chemotherapy is the most important factor for improved survival in lymphoma patients[6]. Since 2004, this treatment step is usually preceded by surgical resection due to the high risk of bowel perforation or hemorrhage during chemotherapy and to treat symptomatic stenosis or perforation[6-10]. In recent years, consolidation therapy with the addition of stem-cell transplantation (SCT) has been successfully applied in some of these patients[11,12]. For UJ, no standard treatment is available. The majority of UJ patients are also treated with systemic chemotherapy (cladribine, 2CDA[13]) and, depending on stenosis-related symptoms, with resection of the ulcerated segment.

Although surgery is an important first-step in the treatment of both UJ and EATL, the results of this intervention, in terms of outcome, morbidity and mortality, have not been analyzed. Here, we evaluate the indications, resectability, morbidity and mortality in our (pre)malignant CD patients, diagnosed at or referred to our Celiac Center Amsterdam, who underwent surgical intervention. Furthermore, to confirm the additive value of surgery, we compared the outcome of this group with patients who underwent chemotherapy without resection.

A total of 40 patients with an established diagnosis of UJ or EATL who underwent surgical resection between January 2002 and November 2013 were included in this analysis. Clinical characteristics, indication for surgery, surgery-related morbidity and mortality and overall survival (OS) were evaluated. Eleven patients with established EATL who underwent chemotherapy without surgical resection were included as a control group for the survival analysis.

A diagnosis of EATL was histologically established according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues[14] and was confirmed histologically by a dedicated pathologist.

The diagnosis of UJ was based on the macroscopic appearance of ulcerative lesions using gastroduodenoscopy, double balloon endoscopy[15] and/or video-capsule endoscopy[16].

Both the indication and the need for patients to be either treated in the acute- or in the elective setting were based on clinical assessment performed by a gastroenterologist and a surgeon. Perforation was defined as the existence of an acute abdomen and/or extraluminal air and mesenteric fatty infiltration seen on computed tomography (CT). During surgery the presence of a perforation was confirmed. When a patient suffered nausea and/or vomiting accompanied by abdominal pain and bowel distension, which was in some cases accompanied by a zone of collapsed bowel seen on CT, the patient was defined as having intestinal stenosis. Surgery in the acute setting was defined as surgical intervention within 24 h after the first presentation. All surgical interventions which occurred after this time-period were defined as elective surgery. A laparoscopic or open-bowel resection was performed depending on localization, the setting (elective/acute) and the preferences of the surgeon performing the surgical intervention. Mobilization and transection of the bowel was performed and the involved segment was resected if possible. Resectability was assessed peri-operatively and defined as radical, partial or unresectable. Radical resection was defined as complete resection of the tumor mass. When some, but not all of tumor mass could be removed it was defined as partial resection. Unresectability was defined as the inability to resect any part of the tumor.

Postoperative patients were either admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or the surgical-gastroenterology ward. Data on postoperative hospital stay, morbidity and the need for reoperation were recorded. Morbidity was assessed using early- and late postoperative complications. Early postoperative complications were defined as direct surgery-related complications occurring within 30 d after the initial surgery. When complications occurred after this time-period and showed a direct relation with the initial surgery, these were defined as late postoperative complications. Overall in-hospital and postoperative mortality were documented, the former being defined as mortality due to any cause during the hospital stay. Postoperative mortality was defined as mortality within 30 d after surgery with a direct relation to the operative procedure.

Chemotherapy was started within 2-5 wk after resection in both EATL and UJ patients depending on the postoperative condition of the patient. In some cases this was followed by autologous or allogeneic SCT. Detailed information on chemotherapy and SCT will be described elsewhere[3].

Follow-up was carried out at 3-mo intervals during the first year and thereafter at 6-mo intervals. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to death. Surviving patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. For the survival analysis, the patients who received chemotherapy without surgical resection were included as a control group.

Continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test. OS was analysed using Kaplan-Meier curves and significance compared using the Log-rank test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, United States).

Between January 2002 and November 2013, 40 consecutive patients with UJ or EATL underwent laparoscopic or open resection. Thirty-five patients had EATL (88%) and the remainder had UJ. Mean age at the time of resection was 62 ± 7 years (range: 48-77). Males were overrepresented (n = 23, 57%). Patient characteristics are described in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Total | Acute setting | Elective setting | P value |

| n = 40 | n = 15 | n = 25 | ||

| Gender M/F | 23/17 | 7/8 | 16/9 | 0.28 |

| (57/43) | (47/53) | (64/36) | ||

| Mean age (yr) at resection (mean ± SD, range) | (62 ± 7, 48-77) | (61 ± 6, 48-70) | (63 ± 7, 49-77) | 0.25 |

| Diagnosis | 0.08 | |||

| EATL | 35 (88) | 15 (100) | 20 (80) | |

| UJ | 5 (12) | 5 (20) | ||

| Indication | < 0.001 | |||

| Perforation | 12 (30) | 10 (67) | 2 (8) | |

| Stenosis | 13 (32) | 4 (27) | 9 (36) | |

| Local resection | 11 (28) | 11 (44) | ||

| Other | 4 (10) | 1 (6) | 3 (12) | |

| Procedure | 0.25 | |||

| Open | 34 (85) | 14 (93) | 20 (80) | |

| Laparoscopic | 6 (15) | 1 (7) | 5 (20) | |

| Conversion (n) | n = 3 | n = 1 | n = 2 | 0.69 |

| Resected | 0.59 | |||

| Jejunum | 27 (67) | 9 (60) | 18 (72) | |

| Jejunum and Ileum | 7 (18) | 3 (20) | 4 (16) | |

| Ileum | 4 (10) | 2 (13) | 2 (8) | |

| Other | 2 (5) | 1 (7) | 1 (4) | |

| Median length of resected segment (cm) (range) | 35 (9-155) | 20 (10-50) | 40 (9-155) | 0.07 |

| Resectability | 0.55 | |||

| Radical resection | 28 (70) | 10 (67) | 18 (72) | |

| Partial resection | 9 (23) | 3 (20) | 6 (24) | |

| Unresectable | 3 (7) | 2 (13) | 1 (4) |

In the majority of patients the surgical procedure was performed in the elective setting (n = 25, 63%). Besides local resection in the case of proven EATL to prevent perforation due to chemotherapy (n = 11), main indications included stenosis (n = 13), perforation (n = 12) and others such as sepsis (n = 1) or exploratory surgery for diagnostic purposes (n = 3). The majority of UJ patients presented with stenosis (n = 3, 60%), whereas none of the UJ patients presented with perforation. The majority of patients (85%) underwent an open procedure; only six patients (15%) underwent laparoscopic surgery, of which half of the procedures were converted to an open procedure. Radical resection of the tumor mass or the ulcerated segment was performed in 70% of patients. In nine patients (23%) the involved segment was only partially resected due to extensive disease such as vascular or mesenteric root involvement. Three patients were found to be unresectable (9%) during the procedure. The latter two groups consisted of EATL patients. When comparing surgery in the acute setting to the elective setting, patients in the acute setting all suffered from EATL with perforation being a significantly more frequent indication for surgery. Indications and operative procedures are listed in Table 1.

In 10 patients (25%) postoperative ICU-stay was required with a median stay of 9 d (range: 1-37). Median hospital stay was ten days (range: 2-63). Early postoperative complications occurred in 14 patients (35%), of which the most important were anastomotic leakage (n = 5) and fever/sepsis (n = 4). Furthermore, postoperative bleeding (n = 2), ileus (n = 1), cardiac failure (n = 1) and wound dehiscence (n = 1) occurred. In eight patients early reoperation was necessary, due to anastomotic leakage (n = 5), postoperative bleeding (n = 2) or wound dehiscence (n = 1). There were no significant differences in early postoperative complications in patients who underwent surgery in the acute setting compared with those who underwent surgery in the elective setting. Postoperative mortality occurred in 3 patients (8%) at a median of 20 d after initial surgery, due to sepsis after anastomotic leakage. This occurred only in patients who underwent surgery in the acute setting (20%; P = 0.02). In-hospital mortality occurred in five patients (13%) at a median of 28 d (range: 14-87) after surgery. Besides the postoperative mortality described above, the other two cases were due to progressive EATL (n = 2).

With a median follow-up of 14 mo (range: 0.5-125) five patients (13%) experienced long-term complications which required reoperation with a median of 58 mo after initial surgery. Stenosis at the side of the initial anastomosis was the most frequently reported long-term complication (n = 4). One patient had anastomotic leakage after stoma reconstruction (n = 1). These patients all underwent surgery in the elective setting (20%; P = 0.08). There were no postoperative complications after secondary-surgery and no postoperative mortality. Data on early and late postoperative morbidity and mortality are provided in Table 2.

| Total | Acute setting | Elective setting | P value | |

| n = 40 | n = 15 | n = 25 | ||

| ICU-stay (n) | 10 | 5 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Median days (range) | 9 (1-37) | 15 (1-37) | 6 (1-28) | 0.31 |

| Median hospital stay (d) (range) | 10 (2-63) | 10 (2-48) | 11 (4-63) | 1.0 |

| Median follow-up after surgery (mo) (range) | 14 (0.5-125) | 6 (0.5-125) | 16 (1-100) | 0.09 |

| Early complications | 14 (35) | 7 (40) | 7 (28) | 0.65 |

| Anastomotic leakage | n = 5 | n = 3 | n = 2 | |

| Fever/sepsis | n = 4 | n = 3 | ||

| Bleeding | n = 2 | n = 2 | ||

| Ileus | n = 1 | n = 1 | ||

| Cardiac failure | n = 1 | n = 1 | ||

| Wound dehiscence | n = 1 | n = 1 | ||

| Reoperation necessary | 8 (20) | 3 (20) | 5 (21) | 0.44 |

| Late complications, | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 5 (20) | 0.08 |

| Stenosis/ileus | n = 4 | n = 4 | ||

| Anastomotic leakage after | n = 1 | n = 1 | ||

| stoma reconstruction | ||||

| Median time after initial surgery (mo) | N.E. | 58 | ||

| Post-operative mortality | 3 (8) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| In-hospital mortality | 5 (13) | 3 (20) | 2 (8) | 0.23 |

During the median follow-up period of 17 mo (range: 2-146) 28 patients (70%) who underwent surgical resection received adjuvant chemotherapy. Only the patients suitable for an aggressive treatment regimen based on clinical condition and age (< 70 years) received SCT after chemotherapy (n = 9, 23%). Long-term follow-up after resection, chemotherapy and SCT will be described elsewhere[3]. During adjuvant chemotherapy, one patient died due to a chemotherapy-related complication (pancytopenia-related pneumonia). None of the resected patients experienced perforation as a side effect of the chemotherapy. Twelve patients (30%) were unable to receive adjuvant chemotherapy after initial resection due to poor clinical condition. Comparing patients who underwent surgery in the acute setting with those who underwent surgery in the elective setting, patients who underwent surgery in the elective setting were significantly more able to receive adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.04) (Table 3).

| Total | Acute setting | Elective setting | P value | |

| n = 40 | n = 15 | n = 25 | ||

| Treatment | 0.04 | |||

| Resection alone | 12 (30) | 8 (53) | 4 (16) | |

| Resection and chemotherapy | 19 (47) | 4 (27) | 15 (60) | |

| Resection, chemotherapy and SCT | 9 (13) | 3 (20) | 6 (24) | |

| Death | 26 (65) | 12 (80) | 14 (56) | 0.12 |

| Overall survival (mo) | 15 | 8 | 19 | 0.05 |

| 1-yr survival | 57% | 40% | 67% | |

| 5-yr survival | 29% | 18% | 34% |

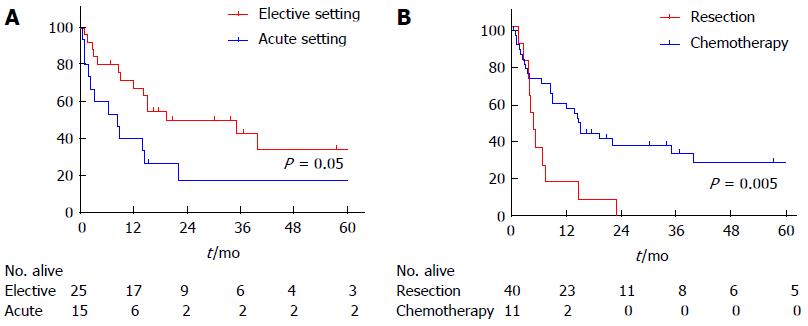

In total, 26 patients died with an OS of 15 mo. One- and five-year OS in this heterogeneous resected group was 57% and 29%, respectively. Patients who underwent surgery in the elective setting showed a significantly better OS of 19 mo compared to 8 mo in patients who underwent surgery in the acute setting. When the outcome of patients who received chemotherapy without surgical resection was compared with patients who underwent surgical resection, the latter group showed a significantly better OS of 14 mo compared to 5 mo in the chemotherapy without resection group (P = 0.005). One year survival in these groups was 57% and 18%, respectively. This survival advantage remained after excluding patients who were able to receive SCT (Figure 1).

Two patients (18%) in the chemotherapy without resection group developed bowel perforation during chemotherapy.

According to our data, surgical resection as the first step in the treatment of (pre)malignant CD is highly recommended in order to treat symptomatic stenosis or perforation, to prevent perforation during chemotherapy and to improve survival. The present study showed a high incidence of postoperative morbidity which was comparable between patients who underwent resection in the acute and in the elective setting. Postoperative mortality was significantly higher in patients who underwent surgery in the acute setting. In these patients, OS was lower than in those treated in the elective setting. Furthermore, significantly more patients who underwent acute surgery could not be treated with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Small intestinal tumours are rare and generally difficult to detect due to the non-specific nature of symptoms, rare incidence and the need for advanced imaging techniques to detect small-bowel lesions. This may lead to diagnosis at a more advanced stage which may lead to a deteriorated clinical condition in (pre)malignant CD patients. We therefore postulated that acute surgery in these patients is a high risk intervention and may lead to serious complications. However, our data concerning both early and late complications showed no differences when acute and elective surgery was compared. The frequency of both early and late complications was relatively high in both groups which may have been due to a delay in diagnosis in both groups. Hence, patients who underwent resection in the acute setting showed more therapy-related mortality and a less favourable OS compared to patients who underwent elective resection. This stresses the importance of early diagnosis of both UJ and EATL.

In patients who are diagnosed with (pre)malignant CD in a progressive stage of disease, poor clinical condition of the patient is partially caused by their poor nutritional status[17]. Nutritional status in most EATL patients is very poor as described in one of our recent papers[18]. This results in a high risk of surgery-related complications, which could also explain the relatively high rate of early-complications after surgery in our cohort. Moreover, nutritional status is an important factor in the ability to receive adjuvant chemotherapy after resection. Therefore, nutritional status should be meticulously evaluated in all patients at presentation and nutrients should be adequately supplied. Moreover, albumin substitution (> 25 g/L) may play an important role in the preoperative conditioning of EATL and UJ, although no scientific evaluation on albumin infusion in these patients is available[19].

In conclusion, although the frequency of early and late post-operative complications is high, the preferred first step of treatment in (pre)malignant CD patients consists of local resection, preferably as early as possible after diagnosis as treatment-related mortality seems to rise in the acute setting and these patients are less likely to be able to receive chemotherapy. Early diagnosis of both UJ and EATL is of utmost importance as elective surgical resection may lower the risk of post-operative mortality and improve overall survival.

A small percentage of celiac disease (CD) patients develop (pre)malignant conditions including ulcerative jejunitis and enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma. No standardized treatment has been established. Early diagnosis is of utmost importance as elective surgical resection may lower the risk of post-operative mortality and improve overall survival. Indications for surgery include clinical symptoms or prevention of perforation during chemotherapy.

A prospective analysis is important to further evaluate morbidity and mortality in patients treated for (pre)malignant CD.

In this study we show that resection is important in (pre)malignant CD patients to improve survival. Optimal treatment, including chemotherapy, is only possible when preceded by surgical resection. Moreover, early diagnosis is important as treatment in the elective setting results in less morbidity and mortality than in the acute setting.

The authors advise surgical resection before chemotherapy in patients with (pre) malignant CD to optimize treatment and improve survival.

CD is a common immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by ingestion of gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma is a rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma that develops in adult-onset CD patients, mostly preceded by refractoriness to a gluten-free diet.

This is an interesting paper dealing with a rare complication in a common disease. The paper is well written. The paper focuses on treatment of pre malignant CD and the authors report that both elective and non-elective surgery has a high rate of complications and local de-bulking is the preferred approach.

| 1. | Biagi F, Klersy C, Balduzzi D, Corazza GR. Are we not over-estimating the prevalence of coeliac disease in the general population? Ann Med. 2010;42:557-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Biagi F, Gobbi P, Marchese A, Borsotti E, Zingone F, Ciacci C, Volta U, Caio G, Carroccio A, Ambrosiano G. Low incidence but poor prognosis of complicated coeliac disease: a retrospective multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:227-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nijeboer P, de Baaij LR, Visser O, Witte BI, Cillessen SA, Mulder CJ, Bouma G. Treatment response in enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma; survival in a large multicenter cohort. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:493-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Malamut G, Chandesris O, Verkarre V, Meresse B, Callens C, Macintyre E, Bouhnik Y, Gornet JM, Allez M, Jian R. Enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma in celiac disease: a large retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Di Sabatino A, Biagi F, Gobbi PG, Corazza GR. How I treat enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:2458-2468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sieniawski MK, Lennard AL. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: epidemiology, clinical features, and current treatment strategies. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:231-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Toma A, Verbeek WH, Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Mulder CJ. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: retrospective evaluation of single-centre experience. Gut. 2007;56:1373-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Gale J, Simmonds PD, Mead GM, Sweetenham JW, Wright DH. Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment of 31 patients in a single center. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:795-803. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, Dederke B, Foss HD, Stein H, Thiel E, Zeitz M, Riecken EO. Intestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on Intestinal non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2740-2746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Thompson JS, Thompson DS, Meyer A. Surgical aspects of celiac disease. Am Surg. 2015;81:157-160. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sieniawski M, Angamuthu N, Boyd K, Chasty R, Davies J, Forsyth P, Jack F, Lyons S, Mounter P, Revell P. Evaluation of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma comparing standard therapies with a novel regimen including autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:3664-3670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | d’Amore F, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, Jantunen E, Hagberg H, Anderson H, Holte H, Österborg A, Merup M, Brown P. Up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: NLG-T-01. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3093-3099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tack GJ, Verbeek WH, Al-Toma A, Kuik DJ, Schreurs MW, Visser O, Mulder CJ. Evaluation of Cladribine treatment in refractory celiac disease type II. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:506-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | The International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO Classification of Tumour of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues. 2008; Available from: http://wenku.baidu.com/view/c8113024a8956bec0875e34a.html. |

| 15. | Van Weyenberg SJ, Van Turenhout ST, Bouma G, Van Waesberghe JH, Van der Peet DL, Mulder CJ, Jacobs MA. Double-balloon endoscopy as the primary method for small-bowel video capsule endoscope retrieval. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:535-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Van Weyenberg SJ, Smits F, Jacobs MA, Van Turenhout ST, Mulder CJ. Video capsule endoscopy in patients with nonresponsive celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:393-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wierdsma NJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Berkenpas M, Mulder CJ, van Bodegraven AA. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are highly prevalent in newly diagnosed celiac disease patients. Nutrients. 2013;5:3975-3992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wierdsma NJ, Nijeboer P, de van der Schueren MA, Berkenpas M, van Bodegraven AA, Mulder CJ. Refractory celiac disease and EATL patients show severe malnutrition and malabsorption at diagnosis. Clin Nutr. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mulder CJ, Wahab PJ, Moshaver B, Meijer JW. Refractory coeliac disease: a window between coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2000;32-37. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Fusaroli P, Reif S S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Liu XM