Published online Oct 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10890

Peer-review started: January 30, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Revised: April 3, 2015

Accepted: June 10, 2015

Article in press: June 10, 2015

Published online: October 14, 2015

Processing time: 269 Days and 10.8 Hours

AIM: To assess numbers and case fatality of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), effects of deprivation and whether weekend presentation affected outcomes.

METHODS: Data was obtained from Information Services Division (ISD) Scotland and National Records of Scotland (NRS) death records for a ten year period between 2000-2001 and 2009-2010. We obtained data from the ISD Scottish Morbidity Records (SMR01) database which holds data on inpatient and day-case hospital discharges from non-obstetric and non-psychiatric hospitals in Scotland. The mortality data was obtained from NRS and linked with the ISD SMR01 database to obtain 30-d case fatality. We used 23 ICD-10 (International Classification of diseases) codes which identify UGIB to interrogate database. We analysed these data for trends in number of hospital admissions with UGIB, 30-d mortality over time and assessed effects of social deprivation. We compared weekend and weekday admissions for differences in 30-d mortality and length of hospital stay. We determined comorbidities for each admission to establish if comorbidities contributed to patient outcome.

RESULTS: A total of 60643 Scottish residents were admitted with UGIH during January, 2000 and October, 2009. There was no significant change in annual number of admissions over time, but there was a statistically significant reduction in 30-d case fatality from 10.3% to 8.8% (P < 0.001) over these 10 years. Number of admissions with UGIB was higher for the patients from most deprived category (P < 0.05), although case fatality was higher for the patients from the least deprived category (P < 0.05). There was no statistically significant change in this trend between 2000/01-2009/10. Patients admitted with UGIB at weekends had higher 30-d case fatality compared with those admitted on weekdays (P < 0.001). Thirty day mortality remained significantly higher for patients admitted with UGIB at weekends after adjusting for comorbidities. Length of hospital stay was also higher overall for patients admitted at the weekend when compared to weekdays, although only reached statistical significance for the last year of study 2009/10 (P < 0.0005).

CONCLUSION: Despite reduction in mortality for UGIB in Scotland during 2000-2010, weekend admissions show a consistently higher mortality and greater lengths of stay compared with weekdays.

Core tip: In this study we have used a large administrative database to demonstrate a significant reduction in mortality from upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Scotland from 2000 to 2010, with stable number of admissions over this time. It is interesting to see this trend during a period of increased incidence of variceal bleeding with a rising burden of chronic liver disease. This is the first report from Scotland demonstrating a “weekend effect” for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients admitted at weekends have significantly higher mortality and a greater length of hospital stay compared with those admitted on weekdays, despite adjustments for comorbidities. These data can help inform resource planning for hospitals at weekends.

- Citation: Ahmed A, Armstrong M, Robertson I, Morris AJ, Blatchford O, Stanley AJ. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Scotland 2000-2010: Improved outcomes but a significant weekend effect. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(38): 10890-10897

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i38/10890.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10890

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common medical emergency with an incidence of 103-172 per 100000 in the United Kingdom[1-3]. This condition accounts for approximately 25000 hospital admissions annually in the United Kingdom[4]. Some studies have suggested an improved outcome over recent years, with others describing a reduced incidence and an association with social deprivation[1,3,5,6].

An increased case fatality among patients presenting to hospitals at weekends has been reported for a number of medical emergencies, including pulmonary embolism[7], myocardial infarction[8] and stroke[9,10]. This has been described as a “weekend effect”. Although some recent studies have suggested a worse outcome for patients presenting with UGIB at weekends, reports on this issue are inconsistent[3,11-13]. A study based on the 2007 United Kingdom national audit did not find a weekend effect for UGIB[14]. There are several processes involved in early management of acute UGIB including risk stratification, early resuscitation, specialist involvement and early endoscopy. Many of these can be affected by variations in hospital staffing levels and resource availability, particularly at weekends. These may impact on patient outcomes including durations of hospital admission and risk of death.

Our aims were to assess trends over time in numbers and case fatality of patients admitted with UGIB in Scotland and examine whether there is an association with social deprivation. We also assessed whether outcomes including case fatality and duration of hospital stay are different for patients who presented at the weekend, compared with those presenting on weekdays. Finally, we examined whether patient comorbidities accounted for any weekend variation.

We sourced data from Information Services Division (ISD) Scotland and National Records of Scotland (NRS) death records for a ten year period between 2000/01 and 2009/10. ISD Scotland is a division of National Services Scotland and part of National Health Services Scotland. It works in partnership with a wide range of organisations to build and maintain high quality national health related datasets and statistical services. We obtained data from the Scottish Morbidity Records (ISD) SMR01 database which holds data on inpatient and day-case hospital discharges from non-obstetric and non-psychiatric hospitals in Scotland. SMR01 episode records are used to identify individual hospital stays. The data is based on Scottish residents only. The mortality data was obtained from NRS and linked with the ISD SMR01 database to obtain 30-d case fatality. This was expressed as percentage of patients who died within 30 d from a hospital admission with a main diagnosis of UGIB. Case fatality figures have been reported in this manuscript as “mortality”, to ensure consistency with other reports. All data records were extracted from the ISD-held permanently linked dataset and were managed subject to ISD information governance rules and processes.

Upper GI bleeding was defined using ICD-10 (International Classification of diseases) codes. It is a standard tool used to classify diseases and maintain medical records allowing later retrieval of information for epidemiological purposes. ICD-10 codes used to define UGIB are summarised in Table 1.

| ICD10 code | Description |

| I850 | Oesophageal varices with bleeding |

| K226 | Gastro-oesophageal laceration - haemorrhage syndrome |

| K228 | Other specified diseases of oesophagus |

| K250 | Gastric ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K252 | Gastric ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K254 | Gastric ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K256 | Chronic or unspecified Gastric ulcer with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K260 | Duodenal ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K262 | Duodenal ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K264 | Duodenal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K266 | Chronic or unspecified Duodenal ulcer with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K270 | Peptic ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K272 | Peptic ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K274 | Peptic ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K276 | Chronic or unspecified Peptic ulcer with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K280 | Gastrojejunal ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K282 | Gastrojejunal ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K284 | Gastrojejunal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K286 | Chronic or unspecified Gastrojejunal ulcer with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K290 | Acute haemorrhagic gastritis |

| K920 | Haematemesis |

| K921 | Melaena |

| K922 | Gastrointestinal haemorrhage, unspecified |

Data on length of hospital admission was calculated using the number of days between date of admission and discharge. The date of discharge was used to allocate an admission to a financial year.

The measure of deprivation used was the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2009. The SIMD is a composite index of multiple deprivations using data from seven domains including income, employment, education, housing, health, crime and geographical access. The SIMD 2009 scores are calculated for residential areas and divides areas of Scottish population into quintiles, giving five equal sized groups with 20% of the population falling into each quintile. Quintile 1 is the most deprived and quintile 5 is the least deprived. Patients’ residential postal code at the time of hospital admission was used to allocate their SIMD 2009 quintile.

We analysed these data for trends in both number of hospital admissions with UGIB and 30-d mortality over time. We compared weekend and weekday admissions for differences in 30-d mortality and length of hospital stay. Weekdays were defined as Monday to Friday with weekends being Saturday and Sunday (days defined as midnight to midnight). Deaths were recorded within 30 d of patients’ admissions; where patients had more than one admission in the 30 d prior to death, the death was only linked to the admission closest to their death, to avoid double-counting.

ISD SMR01 episodic data is not suitable for calculating co-morbidities prevalent at the time of admission, due to coding guidance which requires that only other conditions related to the current diagnosis should be recorded in the secondary diagnosis fields. Therefore to correct for the effect of comorbidities on mortality for weekday and weekend admissions, a five year look back for each admission with UGIB was carried out to determine comorbidities. Comorbidity was measured using the revised Charlson’s comorbidity score as described in Department of Health, information centre’s Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicator (SHMI)[15]. Scores assigned over the five year look back period were combined to give a final score at the point of admission. Data were analysed using SPSS version 21[16].

We used linear regression analysis to assess the trends in number of admissions with UGIB, and 30 d mortality, and to compare trends in relationship between 30 d mortality and deprivation over the 10-year period. Z test of proportions was used to compare proportion of deaths for patients who were admitted on weekdays with proportion of deaths for patients who were admitted on weekends. Two sample t-test was used to compare average length of stay between weekends and weekday admissions with UGIB.

A total of 60643 Scottish residents were admitted to Scottish hospitals with a diagnosis of UGIB during the 10 year period between 2000/01-2009/10. Altogether, there were 73834 admissions as some patients had more than one admission for UGIB during this period. There was no significant variation in the numbers of annual hospital admissions with UGIB over this study period.

Patients admitted at weekends were younger than those admitted on weekdays (median age 60 years vs 62 years, P < 0.0005). Trends in number of hospital admissions, 30-d mortality and length of hospital stay are shown in Table 2.

| 2000/1 | 2001/2 | 2002/3 | 2003/4 | 2004/5 | 2005/6 | 2006/7 | 2007/8 | 2008/9 | 2009/10 | |

| Number of admissions1 | 7674 | 7717 | 7365 | 7106 | 7145 | 7236 | 7316 | 7363 | 7397 | 7717 |

| Median length of stay (d) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Mean length of stay (d) | 9.2 | 9.8 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 7.9 |

| Total number of patients | 6973 | 7002 | 6659 | 6480 | 6508 | 6582 | 6618 | 6634 | 6690 | 6813 |

| Number of deaths | 718 | 744 | 703 | 705 | 663 | 646 | 650 | 625 | 623 | 599 |

| 30-d mortality (%)2 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 8.8 |

There was a significant trend in 30-d mortality which reduced from 10.3% of patients in 2000/01 to 8.8% in 2009/10 (χ2 for trend P < 0.0005). The durations of patients’ hospital admissions fell significantly between 2000/01 and 2009/10 (median from 3.0 to 2.0 d; mean from 9.2 to 7.9 d, both P < 0.0005).

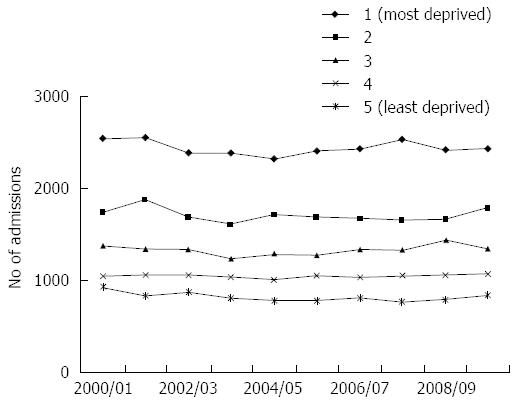

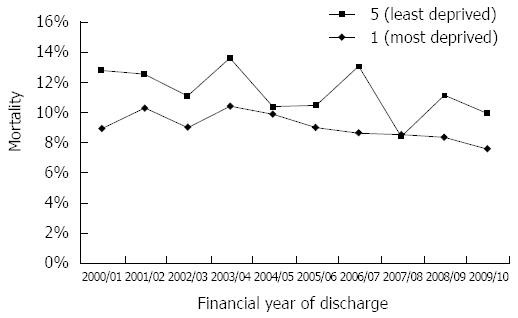

There was a statistically significant association between UGIB and deprivation with a higher number of hospital admissions for patients who were more deprived during this 10 years period (P < 0.05; Figure 1). However patients in the least deprived SIMD category had a higher 30-d mortality compared with the most deprived SIMD category (P < 0.05; Figure 2). Over the ten year study period there was a significant decrease in 30-d mortality for patients in SIMD deprivation quintiles 1, 4 and 5; (P values of χ2 for trend in quintiles 1 to 5 = 0.002, 0.13, 0.08, 0.02, 0.02 respectively).

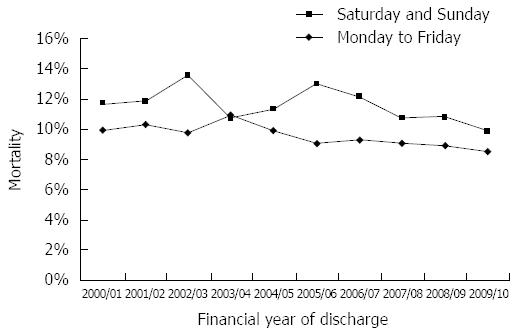

Compared to patients admitted on a weekday, weekend admissions had a significantly higher mortality overall and for seven of the ten years (all but 2003/04, 2004/05 and 2009/10; P < 0.001; Figure 3)

Logistic regression analysis was performed including effects of age, gender, day of the week and comorbidity measured by Charlson’s comorbidity score. People admitted at the weekend with a diagnosis of UGIB had a higher comorbidity score than those admitted during the week (P < 0.001; see Table 3). However, after adjusting for comorbidity, 30 d mortality remained significantly higher for patients admitted with UGIB at weekends.

| Charlson’s co-morbidity score | |||||

| Point of Admission | Number | Median | mean | SD | 95%CI (mean) |

| Weekday | 59061 | 3 | 7.055 | 9.452 | 6.98-7.13 |

| Weekend | 15442 | 4 | 7.603 | 9.613 | 7.45-7.75 |

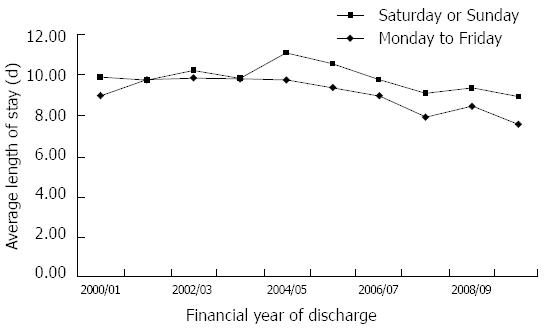

Length of hospital stay was higher overall for patients admitted at the weekend when compared to weekdays (P < 0.0005), although only reached significance for an individual year in the last year of study (2009/10) as shown in Figure 4.

In this study we have used a large administrative database to demonstrate a significant reduction in mortality from UGIB in Scotland from 2000-2010, with a stable number of admissions with UGIB over this time. Admissions with UGIB were closely related to deprivation with a greater number of admissions in the most deprived categories, but higher mortality among the least deprived. Patients admitted at weekends with UGIB had higher mortality than those admitted on weekdays and a longer duration of hospital stay. Although patients admitted at weekend had a higher comorbidity score than those admitted on weekdays, this did not account for the mortality difference. This would suggest that factors other than comorbidity contribute to a worse outcome at weekends.

Our finding of a significant reduction in 30-d mortality from 10.3% to 8.8% over the ten year study period is consistent with some other studies reported from the United Kingdom. Button et al[3] found mortality from UGIB in Wales fell from 11.4% to 8.6% over a seven year period. Crooks et al[5] reported a reduction in 28 d mortality in England for both variceal and non variceal haemorrhage, which fell by 2% and 3% respectively. Similar findings have been reported recently from other European countries. Cavallaro et al[17] found a significant improvement in GI bleeding outcomes in Veneto Italy during the decade 2001-2010; including reduced in-hospital mortality and length of hospital stay. This reduction in mortality may be explained by several factors including advances in endoscopic haemostatic therapies, the use of proton pump inhibitors for ulcer bleeding, vasopressors and antibiotics for variceal haemorrhage and use of risk scoring systems for patients with UGIB. It is interesting that the reduction in overall mortality has occurred during a period of increased incidence of variceal bleeding due to the rising burden of chronic liver disease[6].

Cavallaro et al[17] also reported a reduction in overall admissions with UGIB over the 10 year period between 2001-2010. A recent study from Finland reported a decline in incidence of bleeding gastric and duodenal ulcers between the years 2000-2008[18]. This is in contrast to our finding of a stable incidence in Scotland over a similar time period. The reasons for this are unclear but may be explained by different population characteristics such as social deprivation rates and changing incidence of chronic liver disease.

We found a very strong association between the incidence of UGIB and social deprivation with the highest number of admissions among the most deprived groups. A previous West of Scotland study found a 2.2 fold increased incidence for the most deprived quarter of patients when compared with the least deprived[1]. Recent English and Welsh studies found a similar increased admission rates in the most deprived quintile[3,19]. Similar to our study, the English and Welsh studies did not find an increased mortality gradient with deprivation. One plausible explanation for these findings could be the possibility that patients in most deprived quintile presented with UGIB of lesser severity (such as gastritis or Mallory Weiss bleeding after acute alcohol intoxication) thereby resulting in consistently higher number of admissions but lower mortality. On the other hand, patients in least deprived category had fewer episodes of minor UGIB secondary to gastritis and Mallory Weiss bleeding after alcohol intoxication resulting in fewer admissions. It is possible that the majority of presentations in this least deprived category were due to more severe causes of UGIB, thereby increasing overall mortality.

A higher mortality has been reported for patients admitted at weekends with a variety of medical emergencies, including acute myocardial infarction, stroke, UGIB, abdominal aortic aneurysm, pulmonary embolus and acute epiglottitis[3,7,11,12,20-22]. The UGIB study from Wales found that mortality was 13% higher for patients admitted on the weekends compared with weekdays[3]. They found mortality to be even higher for patients admitted on public holidays. Due to methods of coding, we were unable to separately assess outcome for patients presenting on public holidays.

Two large cohort studies from the United States reported a 10%-20% increased mortality for patients admitted with UGIB at weekends compared with weekdays[12,13]. On the contrary, a recent study based on data collected from the 2007 United Kingdom national UGIB audit did not show a difference in risk adjusted mortality for patients presenting at weekends compared with weekdays, despite a delay in endoscopy for those admitted at weekends[14,23]. This may be due to non-consecutive recording of data in the United Kingdom national audit, with some hospitals contributing a small number of cases which may have created a selection bias[23]. Our data provides a complete national picture by including all hospital admissions for UGIB in Scotland for each year, thereby minimising case selection bias.

There are several possible explanations for our findings of a higher mortality for weekend admissions. Firstly, it may relate to staffing and resource issues. On weekends, hospitals are typically staffed by fewer, less experienced health care providers with poor continuity of care. Many hospitals have relatively limited specialist cover at weekends, including endoscopy staff and interventional radiologists. Some of these issues have been associated with lower quality of care and worse outcome[24,25]. The availability of urgent or next day endoscopy is variable in many hospitals and regions, with the 2007 United Kingdom audit revealing that 52% hospitals had no formal on-call endoscopy rota for emergency procedures, with only 50% patients having endoscopy within 24 h of presentation with acute UGIB[23]. Interestingly a recent study from South Korea suggested that early endoscopy for peptic ulcer bleeding could prevent the deleterious “weekend effect” on outcome[26].

Secondly, it has been suggested that patients admitted over the weekend with a variety of medical conditions have increased co-morbidities or more severe illness[27,28]. It is possible that patients with minor bleeding delay seeking medical attention over the weekend and see their General Practitioner on Monday, while those with more severe bleeding seek emergency care. Due to the observational nature of our study we were unable to determine bleeding severity for individual cases. We found that patients admitted at the weekend with UGIB had a higher Charlson’s co-morbidity score than those admitted during the week. However, even after correction for co-morbidity, patients admitted at the weekend had higher 30-d mortality than those admitted on weekdays. Therefore differences in comorbidity do not fully account for the higher weekend mortality.

Median length of hospital stay for patients admitted at the weekend was also significantly longer over the whole study period, with a numerically higher in-patient stay for patients admitted at weekends compared with weekdays for each year from April, 2003. Dorn et al[11] examined for weekend effect using a large population based data from North America and reported length of hospital stay to be 1.7% longer for weekend admissions with UGIB. Similar findings were reported by Shaheen et al[12] from Canada. In contrast, Button et al[3] reported shorter duration for weekend admissions and a younger patient age group suggesting possibly less severe bleeding, but higher case fatality. The reasons for this remain unclear.

There are several potential limitations of our study. Firstly, the weekend was defined as midnight on Friday to midnight on Sunday. We know that for practical purposes this is not an exact reflection of variations in staffing levels and resources. However for coding reasons, this was the only way to define the weekend for the purposes of this study.

It is possible that coding misclassified some patients with UGIB. In order to minimise this we used a broad combination of ICD 10 codes including some very specific, and others more sensitive but less specific (see Table 1). Another potential weakness could be the accuracy of the coding itself. However, the accuracy of ICD coding has improved in Scotland over time, with the most recent audit from 2011 showing an accuracy of 88%[29]. Therefore error resulting from this is likely to be small.

Thirdly, we were unable to assess the timing of endoscopy and use of drug therapy which may have affected case fatality and duration of hospital admission. Although most international guidelines recommend endoscopy within 24 h of admission with UGIB[30,31], as stated above, during the 2007 audit many United Kingdom hospitals had no formal out-of-hours endoscopy rota and many patients did not undergo endoscopy within 24 h, particularly at weekends[23].

In conclusion, this is the first study from Scotland demonstrating “weekend effect” for UGIB. Although there has been a gradual reduction in mortality for patients admitted with UGIB in Scotland over the decade 2000-2010, those admitted at the weekend have consistently higher mortality and a greater length of stay compared with those admitted on weekdays.

Richard Hunter and John Quinn (Information Statistics Division), for their help with data analysis for the Charlson’s comorbidity scores.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common medical emergency accounting for 25000 hospital admissions annually in the United Kingdom. UGIB has been associated with a high mortality which remains significant but has improved over the years. Recent studies have shown increased mortality for patients presenting to hospitals at weekends for a number of medical emergencies. However, there is inconsistent data on whether UGIB demonstrates a “weekend effect” with worse outcome for patients admitted at weekend with UGIB. In this study the authors aimed to assess the effect of weekend admission on outcome of patients attending hospital with UGIB.

There is a growing interest in hospital resource availability and staffing level at weekends and its impact on patient outcome. This has been examined for several medical emergencies which can inform resource planning for hospitals at weekends.

This is the first report from Scotland confirming a reduction in 30 d mortality from UGIB over the ten year period. These findings are consistent with other reports from the United Kingdom and Europe. However, the present study also found higher mortality and longer length of stay for admissions over the weekend in comparison with weekday admissions.

The authors suggest further studies to identify and understand deficiencies in available staffing and resources at the weekend followed by introduction of measures to improve provision of care at the weekends including availability of formal out of hours endoscopy.

“Weekend effect” describes worse outcome of patients admitted over the weekend when compared to those admitted over the weekend. This effect reflects staffing and resource issues at the weekend, which requires better understanding of these issues, thereby allowing implementation of changes.

This is an interesting study evaluating the upper gastrointestinal bleeding within ten years in Scotland. Interesting data and concerning about the weekend effect. Given the advent of 7 d working in the National Health Services, hopefully this is re-examined for 2005-2015 for example, this effect might be lessened.

| 1. | Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, Blatchford M, Pell J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ. 1997;315:510-514. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222-226. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, Goldacre MJ, Akbari A, Dsilva R, Macey S, Williams JG. Hospitalized incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:64-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Palmer K. Management of haematemesis and melaena. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crooks C, Card T, West J. Reductions in 28-day mortality following hospital admission for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 779] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Shao YH, Wilson AC, Moreyra AE. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1099-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hasegawa Y, Yoneda Y, Okuda S, Hamada R, Toyota A, Gotoh J, Watanabe M, Okada Y, Ikeda K, Ibayashi S. The effect of weekends and holidays on stroke outcome in acute stroke units. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, Bayer N, Hachinski V. Weekends: a dangerous time for having a stroke? Stroke. 2007;38:1211-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dorn SD, Shah ND, Berg BP, Naessens JM. Effect of weekend hospital admission on gastrointestinal hemorrhage outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1658-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:303-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:296-302e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jairath V, Kahan BC, Logan RF, Hearnshaw SA, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the United kingdom: does it display a “weekend effect”? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1621-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Indicator Specification Summary Hospital level Mortality Indicator methodology. Accessed Jan 2014. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/media/11151/Indicator-SpecificationSummary-Hospital-level-Mortality-Indicator-methodology/pdf/SHMI_Specification.pdf. |

| 16. | IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp 2012; . |

| 17. | Cavallaro LG, Monica F, Germanà B, Marin R, Sturniolo GC, Saia M. Time trends and outcome of gastrointestinal bleeding in the Veneto region: a retrospective population based study from 2001 to 2010. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:313-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malmi H, Kautiainen H, Virta LJ, Färkkilä N, Koskenpato J, Färkkilä MA. Incidence and complications of peptic ulcer disease requiring hospitalisation have markedly decreased in Finland. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:496-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Crooks CJ, West J, Card TR. Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage and deprivation: a nationwide cohort study of health inequality in hospital admissions. Gut. 2012;61:514-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117:151-157. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Schmulewitz L, Proudfoot A, Bell D. The impact of weekends on outcome for emergency patients. Clin Med. 2005;5:621-625. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Smith S, Allan A, Greenlaw N, Finlay S, Isles C. Emergency medical admissions, deaths at weekends and the public holiday effect. Cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Use of endoscopy for management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: results of a nationwide audit. Gut. 2010;59:1022-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tarnow-Mordi WO, Hau C, Warden A, Shearer AJ. Hospital mortality in relation to staff workload: a 4-year study in an adult intensive-care unit. Lancet. 2000;356:185-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, Shah MN, Jin L, Guth T, Levinson W. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:866-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Youn YH, Park YJ, Kim JH, Jeon TJ, Cho JH, Park H. Weekend and nighttime effect on the prognosis of peptic ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3578-3584. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Mikulich O, Callaly E, Bennett K, O’Riordan D, Silke B. The increased mortality associated with a weekend emergency admission is due to increased illness severity and altered case-mix. Acute Med. 2011;10:182-187. [PubMed] |

| 28. | de Groot NL, Bosman JH, Siersema PD, van Oijen MG, Bredenoord AJ. Admission time is associated with outcome of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of a multicentre prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:477-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Information Services Division. Accessed Mar 2015. Available from: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Hospital-Care/Publications/2012-05-08/Assessment-of-SMR01Data-2010-2011-ScotlandReport.pdf. |

| 30. | Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, Sinclair P. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | National Institute for health and Clinical Excellence guideline. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: management. 2012 Jun 23. London (UK): NICE 2012; . |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Antoniazzi S, Corbett C S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH