Published online Jul 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i28.8516

Peer-review started: January 29, 2015

First decision: April 13, 2015

Revised: May 7, 2015

Accepted: June 15, 2015

Article in press: June 16, 2015

Published online: July 28, 2015

Processing time: 182 Days and 6.7 Hours

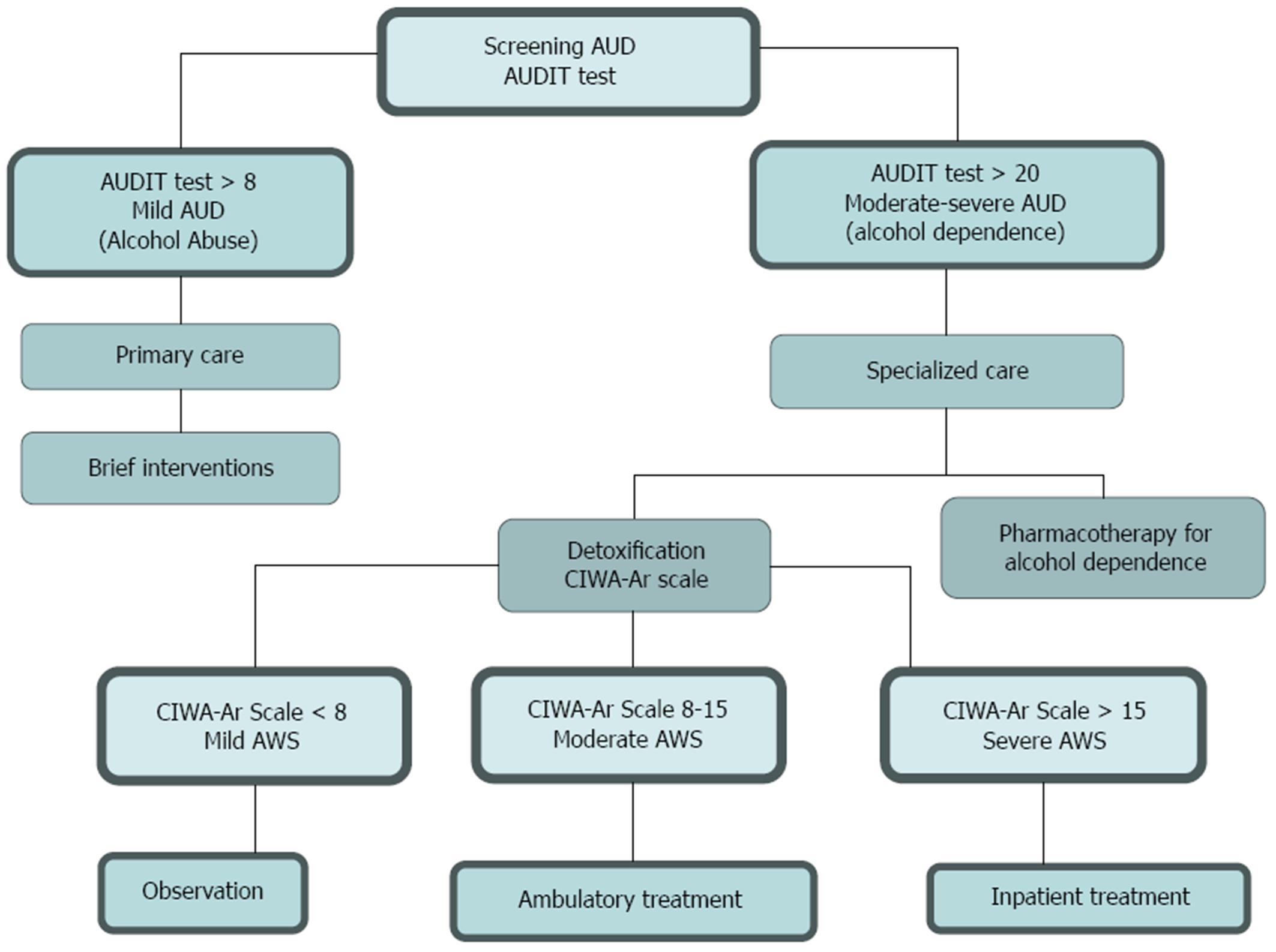

Harmful alcohol drinking may lead to significant damage on any organ or system of the body. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is the most prevalent cause of advanced liver disease in Europe. In ALD, only alcohol abstinence was associated with a better long-term survival. Therefore, current effective therapeutic strategy should be oriented towards achieving alcohol abstinence or a significant reduction in alcohol consumption. Screening all primary care patients to detect those cases with alcohol abuse has been proposed as population-wide preventive intervention in primary care. It has been suggested that in patients with mild alcohol use disorder the best approach is brief intervention in the primary care setting with the ultimate goal being abstinence, whereas patients with moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder must be referred to specialized care where detoxification and medical treatment of alcohol dependence must be undertaken.

Core tip: Current pharmacological treatment to improve long-term survival in patients with alcohol liver disease has failed to achieve this goal. In addition, no major drug development is expected on this field for the next few years. We have described a potential itinerary from management of acute complications from alcohol abuse such as Delirium Tremens or Wernicke´s encephalopathy to prevention and long-term clinical support and monitoring of patients with harmful alcohol consumption. We think our review will provide useful practical guidelines to clinicians dealing with these patients.

- Citation: García MLG, Blasco-Algora S, Fernández-Rodríguez CM. Alcohol liver disease: A review of current therapeutic approaches to achieve long-term abstinence. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(28): 8516-8526

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i28/8516.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i28.8516

While alcohol consumption is commonly accepted and associated with social activity and recreation, some people drink exceedingly high amounts of alcohol and may experience physical, psychological and social devastating effects[1]. Although reliable epidemiological data on damaging alcohol consumption are lacking, it is estimated that it is responsible for 3.8% of global mortality and for 6.5% of deaths in Europe[2-4].

The terms alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), have been replaced by one diagnosis, alcohol use disorders in the DSM Fifth Edition (DSM-V)[5]. Alcohol abuse is similar to mild alcohol use disorder and alcohol dependence comparable to moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. Medical consequences of harmful alcohol drinking may become manifest on any organ or system of the body, consumption levels above 25 g/d of ethanol significantly increased risk of mortality from liver cirrhosis[6].

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is the most prevalent cause of advanced liver disease in Europe, but mortality due to alcoholic cirrhosis separate out from non-alcoholic cirrhosis is not easy to determine[7,8]. Alcohol abstinence is the most important goal in patients with ALD, as abstinence reduces progression to liver cirrhosis and improves long-term survival[9].

Recently, the trial STOPAH which included a large cohort of 1103 patients with alcohol liver disease shown that neither prednisolone or pentoxifylline provided benefit in terms of long-term survival in a sub-analysis, only patients who maintained alcohol abstinence achieved better long-term survival[10], these results highlight the importance of orientating current therapeutic efforts to achieve alcohol abstinence or to minimize alcohol consumption as no new effective specific drug development to treat alcohol liver disease is expected to emerge in the next few years.

While health strategies on harmful alcohol consumption should include large-scale priorities such as tax policies to reduced levels of consumption[11] at clinical level it should be emphasized the importance of identifying patients with abuse and alcohol dependence by using questionnaires and asking about drinking habits (screening) to initiate advice on abstinence or effectively reduce alcohol consumption.

The combination of universal screening in primary care setting to detect patients with alcohol abuse and a brief counseling intervention has been proposed as population-wide preventive intervention[12].

Effective treatment of ALD to reduce alcohol consumption or to achieve complete alcohol abstinence must be based on a multidisciplinary approach which should include public health intervention, addiction behavior and alcohol-induced organ injury management[13]. It has been suggested that in patients with mild alcohol use disorder the best approach is brief intervention in the primary care setting where goal is abstinence whereas in patients with moderate-severe alcohol use disorder must be referred to specialized care[14].

We performed a review and discussion of the current interventions in alcohol use disorders focused on strategies oriented (towards) to achieving long-term abstinence, including screening, psychosocial intervention and currently available pharmacological therapy.

Screening for alcohol disorders in primary care can range from one simple question to an extensive assessment using a standardized questionnaire[15-18]. Questions about alcohol use should be asked to all patients on an annual basis or in response to clinical suspicion on problems that may be alcohol related[19-21]. The best approach in primary care for detecting unhealthy alcohol use is the implementation of a brief validated questionnaire. There are several questionnaires that can identify alcohol use disorders: the CAGE test[22,23], the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST)[24,25] and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)[26-29] (Table 1). The AUDIT is the most extensively validated test though it is not sufficiently brief (it contains 10 items and a scoring index of 0-40)[26]. A score of 8 or greater suggests detrimental alcohol use, and a score of 20 or greater alcohol dependence. The AUDIT includes questions about the quantity and frequency of alcohol use, as well as binge drinking, dependence symptoms, and alcohol-related problems. The AUDIT-C is a shorter version of the AUDIT and includes the first 3 items on excess consumption of the original but still requires scoring[30,31].

| How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? |

| (0) Never [Skip to Qs 9-10] |

| (1) Monthly or less |

| (2) 2 to 4 times a month |

| (3) 2 to 3 times a week |

| (4) 4 or more times a week |

| How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? |

| (0) 1 or 2 |

| (1) 3 or 4 |

| (2) 5 or 6 |

| (3) 7, 8, or 9 |

| (4) 10 or more |

| How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion? |

| (0) Never |

| (1) Less than monthly |

| (2) Monthly |

| (3) Weekly |

| (4) Daily or almost daily |

| Skip to questions 9 and 10 if total score for questions 2 and 3 = 0 |

| How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking? |

| (0) Never |

| (1) Less than monthly |

| (2) Monthly |

| (3) Weekly |

| (4) Daily or almost daily |

| How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? |

| (0) Never |

| (1) Less than monthly |

| (2) Monthly |

| (3) Weekly |

| (4) Daily or almost daily |

| How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? |

| (0) Never |

| (1) Less than monthly |

| (2) Monthly |

| (3) Weekly |

| (4) Daily or almost daily |

| How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? |

| (0) Never |

| (1) Less than monthly |

| (2) Monthly |

| (3) Weekly |

| (4) Daily or almost daily |

| How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? |

| (0) Never |

| (1) Less than monthly |

Patients with positive screening results must be treated with a brief intervention in primary care level. This intervention can help patients with mild alcohol use disorders[32]; however it has also been used to motivate alcohol-dependent patients to enter specialized treatment. The goals for non-dependent individuals include either reduction or advice for safe alcohol consumption.

The active elements of brief intervention are a repeated message from clinicians to patients. Brief intervention with proven efficacy is generally restricted to four or fewer sessions, each session lasting from a few minutes to an hour, and is designed to be conducted by professionals who are not specialists in addictions treatment[33].

Individuals are most likely to initiate behavior changes when they perceive that they have a problem, but some patients are not ready for changes when brief intervention begins, therefore, it is important to assess patient willingness to change when beginning a brief intervention[34]. Rollnick created a 12-question to change “readiness to change” questionnaire for use in matching intervention techniques[35]. Awareness of readiness can be used to provide an appropriate brief intervention[36,37].

The Key components of successful brief intervention are summarized by the acronym FRAMES: Feedback of Personal Risk, Responsibility of the Patient, Advice to Change, Menu of Ways to Reduce Drinking, Empathetic Counseling Style and Self-Efficacy or Optimism of the patient[26]. Goal setting, follow-up and timing also have been identified as important to the effectiveness of brief intervention.

The efficacy of brief intervention has been demonstrated in many studies in patients with non-alcohol-dependence[38,39]. A meta-analysis found that brief intervention decreased the proportion of patients drinking risky amounts of alcohol one year later[40].

Detoxification is the process of weaning a person from a psychoactive substance in a safe and effective manner by gradually tapering the dependence producing substance or by substituting it with a cross-tolerant pharmacological agent and tapering it. This process minimizes the withdrawal symptoms, prevents complications and hastens the process of abstinence from the substance in a more gentle way.

Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant; therefore sudden cessation of alcohol in the chronic user results in over-activity of the central nervous system that results in the alcohol withdrawal syndrome which includes insomnia, anxiety, increased pulse and respiration rates, body temperature, blood pressure and hand tremors[5,41-43]. Once a patient is diagnosed with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, severity may be quantified by using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol -revised (CIWA-Ar) scale[44,45] (Figure 1). Scores on the CIWA-Ar range from 0 to 67; scores lower than 8 indicate mild withdrawal symptoms so detoxification may not be needed, scores from 8 to 15 indicate moderate withdrawal symptoms so detoxification may be done in an outpatient clinic setting, and symptoms are likely to respond to low doses of benzodiazepines, while scores ≥ 15 indicate severe withdrawal symptoms so in-patient referral is more appropriate to close monitoring to prevent seizures and delirium tremens development.

Benzodiazepines are considered the “gold-standard” treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome to reduce symptoms and to prevent progression from minor withdrawal symptoms to major ones[46]. These drugs exert their effect via stimulation of GABA receptors, leading a decrease in neuronal activity and relative sedation[47]. Long-acting benzodiazepines (chlordiazepoxide, diazepam) are preferred to prevent or to treat alcohol withdrawal because their effect results in a smoother course with less chance of recurrent withdrawal or seizures. Short and-intermediate-acting benzodiazepines (lorazepam, oxazepam) are preferred in patients with advanced age, liver failure, respiratory failure and other serious medical co-morbidities[48]. Patients with seizures or delirium tremens require intravenous therapy with benzodiazepines. Refractory delirium tremens can be treated with propofol[49-51].

Carbamazepine and valproate have been studied as an alternative to benzodiazepines in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal, but they have not been consistently proven to be better than benzodiazepines[52-54]. They may be considered in mild withdrawal states due to their advantages of lower sedation and lower chances of dependence or abuse potential. Their use is not recommended in severe withdrawal states[55]. Other anticonvulsants have been studied in alcohol withdrawal syndrome such as gabapentin, tiagabine and phenytoin but they have not shown significant advantages.

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist receptor which has shown effectiveness in reducing withdrawal symptoms and in reducing the risk of relapse after detoxification[56,57]. Beta-blocker drugs and alpha-2 blockers clonidine may be helpful in combination with benzodiazepines to reduce persistent noradrenergic symptoms[58]. Anti-glutamaergic medications (lamotrigine and topiramate) are superior to placebo but have not shown significant advantages over diazepam[59].

Nutritional support is essential as alcoholic patients are frequently malnourished and have high metabolic needs due to their autonomic over-activation[13]. Effective circulating blood volume deficits must be replaced.

Wernicke’ s Encephalopathy (WE) results from cell damage due to chronic thiamine deficiency[60]. This can be prevented by administering parenteral thiamine. All patients suffering alcohol withdrawal should receive parenteral thiamine for 3-5 d[61]. Due to chronic malnutrition, prescription of multivitamin supplements is recommended[62-64].

As mentioned, alcohol abstinence is the most important goal in patients with ALD, as it reduces progression to liver cirrhosis and improves long-term survival[9]. Alcohol detoxification is often the first step in the treatment of alcohol dependence. After detoxification, the vast majority of alcohol dependent patients suffer from relapses[40]. Improvement of the treatment outcome can be achieved by combining psychosocial with pharmacological interventions. Pharmacotherapy is generally recommended for maintenance of abstinence. Medical treatment of alcohol is based on modulating neurotransmitter systems which mediate reinforcement effects of alcohol use[65]. Alcohol dependence represents a heterogeneous disorder that results from a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors, which differ from patient-to-patient, it seems unlikely that one single medication could show efficacy in the majority of alcohol-dependent patients[66,67]. With the goal of abstinence in mind, the patient must be treated for at least six months with an additional six months period of follow-up.

Currently the anti-craving compounds acamprosate and naltrexone as well as the aversion therapeutic agent disulfiram are widely available pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence[68,69]. Because of its long-standing availability, clinicians may be more familiar with disulfiram than with naltrexone or acamprosate[70]. When clinicians decide to use one of the medications, a number of factors may help in choosing which medication to prescribe, such as efficacy, administration frequency, cost, adverse effects and availability.

Pharmacotherapy of alcohol was initiated in 1950 and consisted only of disulfiram, a drug that does not directly influence motivation to drink, but discourages drinking by causing an unpleasant physiologic reaction when alcohol is consumed. Disulfiram is an aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor that results in accumulation of acetaldehyde in the blood (the alcohol primary metabolite), these unpleasant effects driven by alcohol consumption include headache, dyspnoea, arterial hypotension, flushing, sympathetic over-activity, palpitations, nausea and vomiting. Only three trials investigated disulfiram using a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled design[71-73]. One study reported a higher abstinence rate (54% vs 15%) and higher cumulative abstinence duration (69 d vs 30 d) for disulfiram. Two other large studies however, could not show disulfiram superiority with regard to total abstinence for disulfiram vs placebo. Unfortunately, well-designed controlled trials of disulfiram did not show overall reductions in alcohol consumption[74,75].

It is an opioid antagonist that acts through the mu-opioid receptors blockade[76]. Its efficacy in reducing alcohol consumption has been demonstrated in meta-analyses of clinical trials[70,77]. A 2010 meta-analyses of 50 randomized trials with 7793 alcohol-dependent patients found that naltrexone reduced the heavy drinking relapse rate by 83% as compared with the placebo group and decreased drinking days by about a 4%[77]. Naltrexone may be particularly effective in patients with genetic susceptibility[78]. Naltrexone exists in two formulations: oral and intramuscular. Slow-release preparations may improve adherence by reducing the frequency of medication from daily to monthly and a large randomized trial demonstrated its efficacy[79]. Side effects of naltrexone are nausea, headache, dizziness and elevation in liver enzymes. Liver enzymes should be monitored periodically during naltrexone treatment, and given the potential for hepatotoxicity, has not been studied in patients with ALD thus its administration is not recommended in this population[13].

Acamprosate acts as a modulator of the glutamataergic receptor system[80]. Its efficacy in reducing alcohol consumption has been demonstrated in meta-analysis of clinical trials[66,81-83]. A 2010 meta-analysis of 24 randomized trials with 6915 alcohol dependent patients found that acamprosate reduced the risk for relapse to heavy drinking to 86% of the risk in the placebo group and decreased drinking days by about 11%[77]. Side effects of acamprosate include diarrhea, nervousness and fatigue. It can be used in patients with ALD but needs dosage adjustment for renal insufficiency.

It is an opioid antagonist with several potential advantages over naltrexone including absence of dose-dependent liver toxicity, longer acting effects and more effective affinity to central opiate receptors[84]. It has been evaluated in several randomized placebo-controlled trials in alcohol-dependence and all trials reported a reduction of heavy drinking during nalmefene treatment[85-87].

Combining medications offers the possibility of more effective treatment for patients who do not adequately respond to an individual agent. However, the COMBINE study did not find any significant advantage of naltrexone-acamprosate treatment over individual agents or placebo[88].

Whether combining medication with psychosocial treatment improves the outcomes for alcohol use disorders is uncertain, in the COMBINE study no differences were observed with either medication combined with psychosocial treatment compared with the respective medication alone or the psychosocial treatment alone[88].

Given the high relapse rates, further research is urgently needed to develop more effective pharmacotherapy for the treatment of alcohol dependence[89]. Treatment with levetiracetam, a second-generation antiepileptic drug, has been investigated in alcohol dependence. Two randomized clinical trials have been conducted to date and no differences were observed between levetiracetam and placebo for the rate of relapse[90,91].

Topiramate, an anticonvulsivant drug has shown to be effective in improving several drinking related outcomes in four well-designed randomized clinical trials[92-95]. Therefore, off-label use of topiramate can be considered as it is evidence based[96].

Gabapentin, a non-benzodizepine anticonvulsant GABA analogue, has been evaluated positively in two clinical trials in alcohol-dependence, therefore, it represents a further pharmacological treatment option, but these results must be confirmed in future studies[97,98].

The selective GABA-B receptor agonist Baclofen, has been studied in alcohol-dependent patients in four randomized clinical trials, results demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile but conflicting results in terms of efficacy[99-102]. These results might possibly be related to the use of low dosages of baclofen, thus three ongoing randomized clinical trials are investigating the efficacy and safety of high-doses of baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients. Baclofen represents the only alcohol pharmacotherapy tested in patients with alcohol use disorder and significant liver disease; consequently it may represent a promising pharmacotherapy for alcohol-dependent patients with ALD[100,102].

The antiemetic drug ondansetron has been studied in three randomized clinical trials[103-105] showing efficacy when patients were segregated according to their genotypes of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene, thus first clinical evidence suggests that ondansetron might be a further pharmacological strategy for alcohol dependence when used within a pharmacogenetic treatment approach.

New effective drug developments to treat specific organ damage, such as alcohol liver disease is not expected to occur in the next future, for this reason, significant reduction of alcohol consumption is a reasonable goal to decrease progression to liver cirrhosis and improve survival. This goal must be based on a multidisciplinary approach including public health intervention, intervention in the primary care setting and addiction behavior approach management (Table 2). All of these interventions should be combined when appropriate with alcohol-induced organ injury management. In patients with mild alcohol use disorder, the best approach is brief intervention in the primary care setting where the goal is abstinence whereas in patients with moderate-severe alcohol use disorder must be referred to specialized care where detoxification and medical treatment of alcohol dependence must be done.

| Clinical institute withdrawal assessment of alcohol scale, revised (CIWA-AR) | |

| Patient:_____ Date: _____ Time: _____ (24 h clock, midnight = 00:00) | |

| Pulse or heart rate, taken for one minute:_____ Blood pressure:_____ | |

| Nausea and vomiting -- Ask "Do you feel sick to your stomach? Have you vomited?" Observation | Tactile disturbances -- Ask "Have you any itching, pins and needles sensations, any burning, any numbness, or do you feel bugs crawling on or under your skin?" Observation |

| 0 no nausea and no vomiting | 0 none |

| 1 mild nausea with no vomiting | 1 very mild itching, pins and needles, burning or numbness |

| 2 | 2 mild itching, pins and needles, burning or numbness |

| 3 | 3 moderate itching, pins and needles, burning or numbness |

| 4 intermittent nausea with dry heaves | 4 moderately severe hallucinations |

| 5 | 5 severe hallucinations |

| 6 | 6 extremely severe hallucinations |

| 7 constant nausea, frequent dry heaves and vomiting | 7 continuous hallucinations |

| Visual disturbances -- Ask "Does the light appear to be too bright? Is its color different? Does it hurt your eyes? Are you seeing anything that is disturbing to you? Are you seeing things you know are not there?" Observation | Auditory disturbances -- Ask "Are you more aware of sounds around you? Are they harsh? Do they frighten you? Are you hearing anything that is disturbing to you? Are you hearing things you know are not there?" Observation |

| 0 not present | 0 not present |

| 1 very mild sensitivity | 1 very mild harshness or ability to frighten |

| 2 mild sensitivity | 2 mild harshness or ability to frighten |

| 3 moderate sensitivity | 3 moderate harshness or ability to frighten |

| 4 moderately severe hallucinations | 4 moderately severe hallucinations |

| 5 severe hallucinations | 5 severe hallucinations |

| 6 extremely severe hallucinations7 continuous hallucinations | 6 extremely severe hallucinations7 continuous hallucinations |

| Tremor -- Arms extended and fingers spread apart. Observation | Paroxysmal sweats -- Observation |

| 0 no tremor | 0 no sweat visible |

| 1 not visible, but can be felt fingertip to fingertip | 1 barely perceptible sweating, palms moist |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 moderate, with patient's arms extended | 4 beads of sweat obvious on forehead |

| 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 6 |

| 7 severe, even with arms not extended | 7 drenching sweats |

| Anxiety -- Ask "Do you feel nervous?" Observation | Headache, fullness in head -- Ask "Does your head feel different? Does it feel like there is a band around your head?" Do not rate for dizziness or lightheadedness. Otherwise, rate severity |

| 0 no anxiety, at ease | 0 not present |

| 1 mild anxious | 1 very mild |

| 2 | 2 mild |

| 3 | 3 moderate |

| 4 moderately anxious, or guarded, so anxiety is inferred | 4 moderately severe |

| 5 | 5 severe |

| 6 | 6 very severe |

| 7 equivalent to acute panic states as seen in severe delirium or acute schizophrenic reactions | 7 extremely severe |

| Agitation -- Observation | Orientation and clouding of sensorium -- Ask "What day is this? Where are you? Who am I?" |

| 0 normal activity | 0 oriented and can do serial additions |

| 1 somewhat more than normal activity | 1 cannot do serial additions or is uncertain about date |

| 2 | 2 disoriented for date by no more than 2 calendar days |

| 3 | 3 disoriented for date by more than 2 calendar days |

| 4 moderately fidgety and restless | 4 disoriented for place/or person |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 paces back and forth during most of the interview, or constantly thrashes about | |

| Total CIWA-Ar Score ______ | |

| Rater's Initials ______ | |

| Maximum Possible Score 67 | |

We thank Mrs. Dolores MacFarland for writing assistance.

| 1. | Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:596-607. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223-2233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2298] [Cited by in RCA: 2379] [Article Influence: 139.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | World Health Organization. European Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2010. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/128065/e94533.pdf. |

| 4. | Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Didorders. 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association 2013; . |

| 6. | Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Torchio P. Meta-analysis of alcohol intake in relation to risk of liver cirrhosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:381-392. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Zatoński WA, Sulkowska U, Mańczuk M, Rehm J, Boffetta P, Lowenfels AB, La Vecchia C. Liver cirrhosis mortality in Europe, with special attention to Central and Eastern Europe. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Leon DA, McCambridge J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950 to 2002: an analysis of routine data. Lancet. 2006;367:52-56. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Peters L, Pham BN, Batel P, Rueff B, Valla DC. Five-year survival predictive factors in patients with excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis. Effect of alcoholic hepatitis, smoking and abstinence. Liver Int. 2003;23:45-53. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1619-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373:2234-2246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 39.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J; U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:557-568. [PubMed] |

| 13. | European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:554-556. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Canagasaby A, Vinson DC. Screening for hazardous or harmful drinking using one or two quantity-frequency questions. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:208-213. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O’Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1977-1989. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Moyer VA; Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Taj N, Devera-Sales A, Vinson DC. Screening for problem drinking: does a single question work? J Fam Pract. 1998;46:328-335. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Vinson DC, Kruse RL, Seale JP. Simplifying alcohol assessment: two questions to identify alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1392-1398. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121-1123. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Selzer ML. The Michigan alcoholism screening test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653-1658. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Storgaard H, Nielsen SD, Gluud C. The validity of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST). Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29:493-502. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, Sporleder JL, Maynard C, Burman ML, Kivlahan DR. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:821-829. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Williams R, Vinson DC. Validation of a single screening question for problem drinking. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:307-312. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Friedmann PD, Saitz R, Gogineni A, Zhang JX, Stein MD. Validation of the screening strategy in the NIAAA “Physicians’ Guide to Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems”. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:234-238. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1208-1217. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Rubinsky AD, Dawson DA, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. AUDIT-C scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a U.S. general population sample of drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1380-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97:279-292. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88:315-335. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press 2002; . |

| 35. | Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short ‘readiness to change’ questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. Br J Addict. 1992;87:743-754. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Collins SE, Logan DE, Neighbors C. Which came first: the readiness or the change? Longitudinal relationships between readiness to change and drinking among college drinkers. Addiction. 2010;105:1899-1909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gavin DR, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Evaluation of the readiness to change questionnaire with problem drinkers in treatment. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10:53-58. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, Pienaar E, Schlesinger C, Campbell F, Saunders JB, Burnand B, Heather N. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28:301-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Emmen MJ, Schippers GM, Bleijenberg G, Wollersheim H. Effectiveness of opportunistic brief interventions for problem drinking in a general hospital setting: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;328:318. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Beich A, Thorsen T, Rollnick S. Screening in brief intervention trials targeting excessive drinkers in general practice: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327:536-542. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Kosten TR, O’Connor PG. Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1786-1795. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Santavy P. Multidisciplinary approach to a Marfan syndrome patient with emphasis on cardiovascular complications. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2013;157:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, Gorelick DA, Guillaume JL, Hill A, Jara G, Kasser C, Melbourne J; Working Group on the Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium, Practice Guidelines Committee, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1405-1412. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84:1353-1357. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Krupitsky E, Rudenko AA, Flannery BA, Krystal JH. Multidimensionality of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist: a factor analysis of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist and CIWA-Ar. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:612-618. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal. CMAJ. 1999;160:649-655. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Schuckit MA. Ethanol and methanol. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 2011; 629-647. |

| 48. | Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, Davoli M. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD005063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Hughes DW, Vanwert E, Lepori L, Adams BD. Propofol for benzodiazepine-refractory alcohol withdrawal in a non-mechanically ventilated patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:112.e3-112.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Coomes TR, Smith SW. Successful use of propofol in refractory delirium tremens. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:825-828. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Lorentzen K, Lauritsen AØ, Bendtsen AO. Use of propofol infusion in alcohol withdrawal-induced refractory delirium tremens. Dan Med J. 2014;61:A4807. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Barrons R, Roberts N. The role of carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine in alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35:153-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lucht M, Kuehn KU, Armbruster J, Abraham G, Gaensicke M, Barnow S, Tretzel H, Freyberger HJ. Alcohol withdrawal treatment in intoxicated vs non-intoxicated patients: a controlled open-label study with tiapride/carbamazepine, clomethiazole and diazepam. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:168-175. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Hillbom M, Tokola R, Kuusela V, Kärkkäinen P, Källi-Lemma L, Pilke A, Kaste M. Prevention of alcohol withdrawal seizures with carbamazepine and valproic acid. Alcohol. 1989;6:223-226. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Polycarpou A, Papanikolaou P, Ioannidis JP, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Anticonvulsants for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD005064. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Addolorato G, Leggio L, Abenavoli L, Caputo F, Gasbarrini G. Baclofen for outpatient treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:24. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Liu J, Wang LN. Baclofen for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD008502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Prater CD, Miller KE, Zylstra RG. Outpatient detoxification of the addicted or alcoholic patient. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1175-1183. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Krupitsky EM, Rudenko AA, Burakov AM, Slavina TY, Grinenko AA, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Petrakis IL, Zvartau EE, Krystal JH. Antiglutamatergic strategies for ethanol detoxification: comparison with placebo and diazepam. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:604-611. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Thomson AD, Cook CC, Touquet R, Henry JA; Royal College of Physicians, London. The Royal College of Physicians report on alcohol: guidelines for managing Wernicke’s encephalopathy in the accident and Emergency Department. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:513-521. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Rees E, Gowing LR. Supplementary thiamine is still important in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Singal AK, Charlton MR. Nutrition in alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:805-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Teixeira J, Mota T, Fernandes JC. Nutritional evaluation of alcoholic inpatients admitted for alcohol detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:558-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Cook CC, Hallwood PM, Thomson AD. B Vitamin deficiency and neuropsychiatric syndromes in alcohol misuse. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:317-336. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Garbutt JC, West SL, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Crews FT. Pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999;281:1318-1325. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Litten RZ, Egli M, Heilig M, Cui C, Fertig JB, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Moss H, Huebner R, Noronha A. Medications development to treat alcohol dependence: a vision for the next decade. Addict Biol. 2012;17:513-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 67. | Testino G, Leone S, Borro P. Treatment of alcohol dependence: recent progress and reduction of consumption. Minerva Med. 2014;105:447-466. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108:275-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Bouza C, Angeles M, Muñoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99:811-828. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R, Kim MM, Shanahan E, Gass CE, Rowe CJ. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1889-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Niederhofer H, Staffen W. Comparison of disulfiram and placebo in treatment of alcohol dependence of adolescents. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:295-297. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Fuller RK, Roth HP. Disulfiram for the treatment of alcoholism. An evaluation in 128 men. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:901-904. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Fuller RK, Branchey L, Brightwell DR, Derman RM, Emrick CD, Iber FL, James KE, Lacoursiere RB, Lee KK, Lowenstam I. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. A Veterans Administration cooperative study. JAMA. 1986;256:1449-1455. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Suh JJ, Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, O’Brien CP. The status of disulfiram: a half of a century later. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:290-302. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Jørgensen CH, Pedersen B, Tønnesen H. The efficacy of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1749-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1734-1739. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Vecchi S, Srisurapanont M, Soyka M. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD001867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, Pettinati H, Gelernter J, Volpicelli JR, O’Brien CP. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1546-1552. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Loewy JW, Ehrich EW; Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1617-1625. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Mann K, Kiefer F, Spanagel R, Littleton J. Acamprosate: recent findings and future research directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1105-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Lehert P, Vecchi S, Soyka M. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD004332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Mason BJ, Lehert P. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence: a sex-specific meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:497-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Higuchi S. Efficacy of acamprosate for the treatment of alcohol dependence long after recovery from withdrawal syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in Japan (Sunrise Study). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:181-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Soyka M. Nalmefene for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a current update. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:675-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Gual A, He Y, Torup L, van den Brink W, Mann K; ESENSE 2 Study Group. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, efficacy study of nalmefene, as-needed use, in patients with alcohol dependence. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1432-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Mann K, Bladström A, Torup L, Gual A, van den Brink W. Extending the treatment options in alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled study of as-needed nalmefene. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:706-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Karhuvaara S, Simojoki K, Virta A, Rosberg M, Löyttyniemi E, Nurminen T, Kallio A, Mäkelä R. Targeted nalmefene with simple medical management in the treatment of heavy drinkers: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1179-1187. [PubMed] |

| 88. | Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003-2017. [PubMed] |

| 89. | Müller CA, Geisel O, Banas R, Heinz A. Current pharmacological treatment approaches for alcohol dependence. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:471-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Richter C, Effenberger S, Bschor T, Bonnet U, Haasen C, Preuss UW, Heinz A, Förg A, Volkmar K, Glauner T. Efficacy and safety of levetiracetam for the prevention of alcohol relapse in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients: a randomized trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Fertig JB, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Mattson ME, Ransom J, Rickman WJ, Scott C, Ciraulo D, Green AI. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of levetiracetam extended-release in very heavy drinking alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1421-1430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL, DiClemente CC, Roache JD, Lawson K, Javors MA, Ma JZ. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1677-1685. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, Wiegand F, Mao L, Beyers K, McKay A, Ait-Daoud N, Anton RF, Ciraulo DA. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1641-1651. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Baltieri DA, Daró FR, Ribeiro PL, de Andrade AG. Comparing topiramate with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2008;103:2035-2044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Rubio G, Martínez-Gras I, Manzanares J. Modulation of impulsivity by topiramate: implications for the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:584-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, Finney JW. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1481-1488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Furieri FA, Nakamura-Palacios EM. Gabapentin reduces alcohol consumption and craving: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1691-1700. [PubMed] |

| 98. | Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shadan F, Kyle M, Begovic A. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:70-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Addolorato G, Caputo F, Capristo E, Domenicali M, Bernardi M, Janiri L, Agabio R, Colombo G, Gessa GL, Gasbarrini G. Baclofen efficacy in reducing alcohol craving and intake: a preliminary double-blind randomized controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:504-508. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, Abenavoli L, D’Angelo C, Caputo F, Zambon A. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:1915-1922. [PubMed] |

| 101. | Garbutt JC, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Gallop R, Kalka-Juhl L, Flannery BA. Efficacy and safety of baclofen for alcohol dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1849-1857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Bedogni G, Caputo F, Gasbarrini G, Landolfi R; Baclofen Study Group. Dose-response effect of baclofen in reducing daily alcohol intake in alcohol dependence: secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:312-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Johnson BA, Roache JD, Javors MA, DiClemente CC, Cloninger CR, Prihoda TJ, Bordnick PS, Ait-Daoud N, Hensler J. Ondansetron for reduction of drinking among biologically predisposed alcoholic patients: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:963-971. [PubMed] |

| 104. | Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Seneviratne C, Roache JD, Javors MA, Wang XQ, Liu L, Penberthy JK, DiClemente CC, Li MD. Pharmacogenetic approach at the serotonin transporter gene as a method of reducing the severity of alcohol drinking. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:265-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Johnson BA, Seneviratne C, Wang XQ, Ait-Daoud N, Li MD. Determination of genotype combinations that can predict the outcome of the treatment of alcohol dependence using the 5-HT(3) antagonist ondansetron. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1020-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Ocker M, Shimizu Y S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM