Published online Jul 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8467

Peer-review started: January 22, 2015

First decision: February 10, 2015

Revised: February 25, 2015

Accepted: April 17, 2015

Article in press: April 17, 2015

Published online: July 21, 2015

Processing time: 181 Days and 6.7 Hours

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare protein-losing enteropathy with lymphatic leakage into the small intestine. Dilated lymphatics in the small intestinal wall and mesentery are observed in this disease. Laboratory tests of PIL patients revealed hypoalbuminemia, lymphocytopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia and increased stool α-1 antitrypsin clearance. Cell-mediated immunodeficiency is also present in PIL patients because of loss of lymphocytes. As a result, the patients are vulnerable to chronic viral infection and lymphoma. However, cases of PIL with chronic viral infection, such as human papilloma virus-induced warts, are rarely reported. We report a rare case of PIL with generalized warts in a 36-year-old male patient. PIL was diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and colonoscopic biopsy with histological tissue confirmation. Generalized warts were observed on the head, chest, abdomen, back, anus, and upper and lower extremities, including the hands and feet of the patient.

Core tip: Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) patients are associated with cell-mediated immunodeficiency. Therefore, PIL patients are vulnerable to viral infection. However, PIL with warts caused by human papilloma virus is very rare. We report a rare case of PIL with generalized warts.

- Citation: Lee SJ, Song HJ, Boo SJ, Na SY, Kim HU, Hyun CL. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia with generalized warts. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(27): 8467-8472

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i27/8467.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8467

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare congenital disorder, characterized by dilated intestinal lymphatics resulting in lymph leakage and protein-losing enteropathy[1]. As a result, hypoalbuminemia, lymphopenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia are observed in PIL patients[2]. Clinical manifestations of PIL, including edema, diarrhea and ascites, present at a young age. Most patients are diagnosed in childhood, but some cases are diagnosed as adolescents or adults. However, the diagnosis of this disease is difficult and rare, the etiology and prevalence are unclear. PIL patients are associated with cell-mediated immunodeficiency caused by loss of lymphocytes, especially CD4+ T cells. Therefore, PIL patients are vulnerable to viral infection or neoplasms, such as lymphomas[3]. PIL associated with generalized warts is very rarely reported. We report a rare case of PIL with generalized warts.

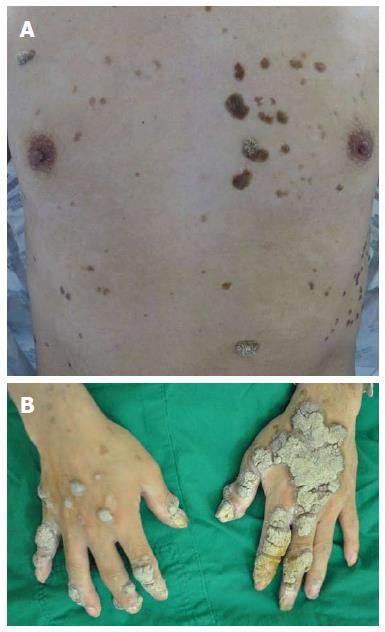

A 36-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a 3-mo history of diarrhea and weight loss (5 kg). He had generalized warts over his entire body, including both hands and feet, with an initial onset at age 10. He was treated for pulmonary tuberculosis in early adolescence. He had no recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis or other organism-induced infections. He had no specific family history. He was a social drinker and a 15 pack per year smoker. Height was 164.9 cm, body weight 49.1 kg, and body mass index 18 kg/m2. Physical examination of the head, chest and abdomen was normal except for generalized warts and both pretibial pitting edema. The warts were distributed on the head, chest, abdomen, back, anus, and upper and lower extremities, including the hands and feet (Figure 1).

Result of a complete blood count showed normal white blood cell count of 6800/mm3, with a differential count of 62.3% neutrophils (normal range, 50%-70%), and decreased lymphocytes (12.4%, normal range, 20%-44%). Hemoglobin was 13.9 g/dL with normal hematocrit (39.8%) and platelet count at 198000/mm3. Other laboratory tests showed low serum total protein level (4.5 g/dL) with hypoalbuminemia (albumin, 2.3 g/dL). There was no evidence of proteinuria on urinalysis. Liver and renal function tests were normal. Flow cytometry of peripheral blood lymphocytes revealed a decrease in CD4+ T cell rate (24.4%), normal CD8+ T cell rate (31.2%) and normal CD3+ T cell count (54.7%, normal: 49%-80%). Quantitative serum immunoglobulins showed an IgG of 653.4 mg/dL (normal range, 700-1600 mg/dL), IgA of 229.8 (normal range, 70-400 mg/dL) and an IgM of 64.2 mg/dL (normal range, 40-230 mg/dL). HIV, HBV, HCV serologies were negative. Stool collection test (24-h) revealed increased stool α-1 antitrypsin clearance (220.11 mL/24 h, normal range, 15 ± 3 mL/24 h).

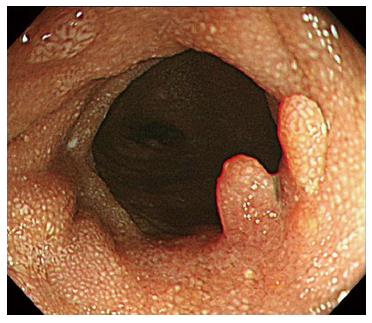

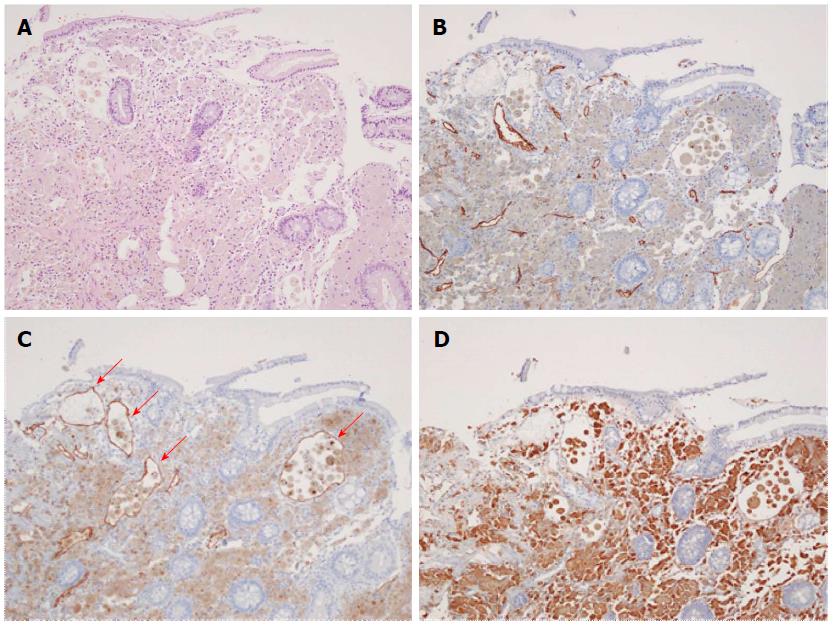

Abdominopelvic computerized tomography showed diffuse mucosal thickening and enhancement throughout the small bowel, with multiple lymph nodes in the left gastric, portahepatis, portocaval and mesenteric areas (Figure 2). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed diffuse mucosal edema in the duodenum. Colonoscopy revealed white mucosal plaques and spots in the terminal ileum and diffuse mucosal edema of the colon (Figure 3). Capsule endoscopy showed diffuse multifocal white mucosal plaques from the proximal jejunum to the terminal ileum (Figure 4). On histological examination of the terminal biopsy specimens, an HE stain showed dilated lymphatic vessels with many foamy macrophages in the lamina propria, consistent with lymphangiectasia. CD34 staining showed normal vascular endothelial cells. D2-40 stained endothelial cells were also observed, which indicated dilated lymphatics. Also observed were CD-68 stained macrophages, which aggregated to uptake lipids leaking from dilated lymphatics (Figure 5).

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with PIL, and the warts were associated with T-cell mediated immunological abnormalities. A low-fat/high protein diet was started to decrease lymphatic pressure and blockade. Medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) are directly absorbed into the blood stream; therefore, he was also prescribed an MCTs diet. After the dietary treatment diet, diarrhea was diminished by degrees and improved a week later.

Intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) is a rare disease, characterized by an abnormal lymphatic system of small intestinal wall and mesentery inducing leakage of lymphocytes and protein loss into the gastrointestinal tract. IL can be classified as primary and secondary IL by cause. PIL is a congenital abnormality of the lymphatic system. Some studies reported genetic factors associated with the hereditary lymphatic disease, and other studies reported regulatory signals involved in lymphangiogenesis. The regulatory molecules lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 are associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia[4]. Oh et al[5] suggested depletion of 4q25 is associated with lymphangiectasia. However, the relationship between gene mutation and lymphangiectasia is unclear.

Secondary IL is an acquired form, by obstructed lymphatic flow, which is induced by other factors. Neoplasms (lymphoma), infections (Whipple disease, parasite infection, intestinal tuberculosis), inflammation (Crohn’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus), bowel obstruction, fibrosis of drainage tracts (sclerosing mesenteritis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, post-radiation fibrosis), hepatic cirrhosis, constrictive pericarditis, and abdominal surgery can be causes of secondary IL[6-9]. Our patient was diagnosed with PIL because his symptoms arose at an early age and showed no evidence of secondary IL.

Stool collection test for 24-h was used to measure stool α-1 antitrypsin clearance to prove protein-losing enteropathy. Alpha-1 antitrypsin is an intrinsic protein, and has a similar molecular weight to albumin. It has characteristics of negative reabsorption from the intestine and negative secretion into the bowel. The 24-h stool collection test in our patient revealed increased stool α-1 antitrypsin clearance. As a cause of hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia, there was no evidence of increased protein catabolism status, such as infection, and lack of proteinuria in urinalysis, which suggested protein-losing enteropathy.

Loss of lymphatic fluid-containing lymphocytes in the intestine is a specific finding of intestinal lymphangiectasia, which is not found in other protein-losing enteropathies. Although B-lymphocytes, natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells may decrease in the disease, loss of CD4+ T cells is observed predominantly[10]. Humoral and cellular immunodeficiency can arise in lymphopenia; however, lack of recurrent infections was observed in the PIL patients. Lynn et al[3] reported that while naïve CD4+ T cells were decreased, memory and effector CD4+ T cells were preserved in PIL patients, which suggested that preserving T cells carry out the role of preventing infections. Chronic viral infections and neoplasms, such as lymphoma, may occur in patients with cell-mediated immunodeficiency[11]. PIL accompanied with viral infections and/or lymphoma has been reported in some cases. However, PIL with warts caused by human papilloma virus is very rare. To the best of our knowledge, PIL with generalized warts has been reported in only six patients in five reports. Four patients had supervening lymphoma, and all six patients had PIL with warts. The characteristics of the five case reports are summarized in Table 1[3,11-14].

| Ref. | Sex | Age at diagnosis of PIL | Accompanied disease | Treatment for PIL |

| Ross et al[12], 1971 | M | 30 | NA | Dietary therapy |

| Diuretics | ||||

| Steroid | ||||

| Ward et al[13], 1977 | M | 29 | Lymphoma | Dietary therapy |

| Diuretics | ||||

| Gumà et al[14], 1998 | F | 34 | Lymphoma | Dietary therapy |

| Bouhnik et al[11], 2000 (2 cases) | F | 11 | Lymphoma | Dietary therapy |

| F | 58 | Lymphoma | NA | |

| Lynn et al[3], 2004 | M | 55 | NA | Dietary therapy, octreotide |

| Present case | M | 36 | No accompanying disease | Dietary therapy |

Diagnosis of PIL is not easy, because abnormal lymphatic lesions are usually distributed in the small intestine. Detection of lesions by upper gastroscopy and colonoscopy is limited, and radiological examinations cannot confirm the diagnosis. As a result, double balloon enteroscopy or surgical methods are used for pathological examination in some cases. Double balloon enteroscopy can be used to perform a biopsy, and also reported much higher diagnosis rate than capsule endoscopy[15]. In our patient, the abnormal state of the small intestine tissues was determined in the terminal ileum by colonoscopic biopsy. Therefore, we performed capsule endoscopy to observe the entire small intestinal mucosa. Although capsule endoscopy cannot be used to obtain a biopsy, it is very useful and is a relatively easy, comfortable method to examine mucosal changes in the small intestine[16]. In our patient, capsule endoscopy showed multiple whitish spots, thickened villi and edematous mucosa of the small intestine. These endoscopic findings showed typical mucosal lesions of PIL.

Dietary treatment is the first method recommended to treat PIL. There is no curable and standard treatment of PIL. Lipid elements in foods increase lymphatic pressure and, as a result, cause lymphatic leakage into the intestinal lumen. To lower the lymphatic pressure and ease the blockage, a low-fat/high-protein diet is prescribed to PIL patients. MCTs are directly absorbed into the bloodstream, resulting in a bypass of the lymphatic system. They are secreted into the portal systems, directly. MCTs decrease lymphatic pressure and protein loss into the intestine[17]. The use of octreotide for treatment of lymphangiectasia was reported in some cases[18]. It decreases intestinal blood flow and triglyceride absorption. Consequently, it reduces lymphatic pressure, thereby reducing the loss of protein and lymphatic fluid. However, symptoms of lymphangiectasia can relapse after the interruption of an agent, which is a limitation of octreotide treatment. Corticosteroid and antiplasmin may be prescribed in some cases, but their efficacies are variable and insufficient[19,20]. Octreotide, antiplasmin, and corticosteroid therapies can be used as an optional treatment in patients with no response after the dietary approach. Our patient improved after dietary treatment and intravenous nutrition, thus other treatment options were not considered.

To summarize, PIL patients are vulnerable to chronic viral infection and lymphoma. Cell-mediated immunodeficiency is present in PIL patients because of loss of lymphocytes. Many cases of PIL patients have been reported, but patients with PIL and generalized warts are rare. We report a rare case of PIL with generalized warts.

A 36-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a 3-mo history of diarrhea and weight loss (5 kg).

Body mass index of the patient was 18 kg/m2 and warts were noted on the head, chest, abdomen, back, anus, and the upper and lower extremities, including the hands and feet.

Protein losing enteropathy (inflammatory bowel disease, amyloidosis, congestive heart failure, portal hypertensive gastroenteropathy, intestinal lymphoma).

Laboratory tests showed low serum total protein level (4.5 g/dL) with hypoalbuminemia (albumin, 2.3 g/dL), decreased lymphocytes (12.4%, normal range, 20%-44%) and increased stool α-1 antitrypsin clearance (220.11 mL/24 h; normal range, 15 ± 3 mL/24 h).

Abdominopelvic computerized tomography showed diffuse mucosal thickening and enhancement throughout the small bowel, with multiple lymph nodes in the left gastric, portahepatis, portocaval and mesenteric areas.

On histological examination of the terminal biopsy specimens, the HE stain showed dilated lymphatic vessels with many foamy macrophages in the lamina propria, consistent with lymphangiectasia. A CD34 stain showed normal vascular endothelial cells.

A low-fat/high protein and medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) diet was started to decrease lymphatic pressure and blockade.

Many cases of PIL patients have been reported, but patients of PIL with generalized warts are rare.

PIL is a rare protein-losing enteropathy with lymphatic leakage into the small intestine.

PIL patients are vulnerable to chronic viral infection and lymphoma. However, few cases of PIL with chronic viral infection, such as human papilloma virus-induced warts, have been reported. We report a rare case of PIL with generalized warts.

This is an interesting case report with a very good theoretical presentation of the underlying disease. It is well written and well presented.

| 1. | Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 2. | Brasitus TA, Bissonnette M. Protein-losing enteropathy. Gastrointestinal and liver diseases: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1998; 369-375. |

| 3. | Lynn J, Knight AK, Kamoun M, Levinson AI. A 55-year-old man with hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphopenia, and unrelenting cutaneous warts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:409-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hokari R, Kitagawa N, Watanabe C, Komoto S, Kurihara C, Okada Y, Kawaguchi A, Nagao S, Hibi T, Miura S. Changes in regulatory molecules for lymphangiogenesis in intestinal lymphangiectasia with enteric protein loss. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e88-e95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, Han SJ, Lee JS, Park JY, Song SY. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nelson DL, Blaese RM, Strober W, Bruce R, Waldmann TA. Constrictive pericarditis, intestinal lymphangiectasia, and reversible immunologic deficiency. J Pediatr. 1975;86:548-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wilkinson P, Pinto B, Senior JR. Reversible protein-losing enteropathy with intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to chronic constrictive pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:1178-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Broder S, Callihan TR, Jaffe ES, DeVita VT, Strober W, Bartter FC, Waldmann TA. Resolution of longstanding protein-losing enteropathy in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia after treatment for malignant lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:166-168. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chew CK, Jarzylo SV, Valberg LS. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis with protein-losing enteropathy and duodenal obstruction successfully treated with corticosteroids. Can Med Assoc J. 1966;95:1183-1188. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Fuss IJ, Strober W, Cuccherini BA, Pearlstein GR, Bossuyt X, Brown M, Fleisher TA, Horgan K. Intestinal lymphangiectasia, a disease characterized by selective loss of naive CD45RA+ lymphocytes into the gastrointestinal tract. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4275-4285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bouhnik Y, Etienney I, Nemeth J, Thevenot T, Lavergne-Slove A, Matuchansky C. Very late onset small intestinal B cell lymphoma associated with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia and diffuse cutaneous warts. Gut. 2000;47:296-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ross JD, Reid KD, Ambujakshan VP, Kinloch JD, Sircus W. Recurrent pleural effusion, protein-losing enteropathy, malabsorption, and mosaic warts associated with generalized lymphatic hypoplasia. Thorax. 1971;26:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ward M, Le Roux A, Small WP, Sircus W. Malignant lymphoma and extensive viral wart formation in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia and lymphocyte depletion. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:753-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gumà J, Rubió J, Masip C, Alvaro T, Borràs JL. Aggressive bowel lymphoma in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia and widespread viral warts. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1355-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takenaka H, Ohmiya N, Hirooka Y, Nakamura M, Ohno E, Miyahara R, Kawashima H, Itoh A, Watanabe O, Ando T. Endoscopic and imaging findings in protein-losing enteropathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chamouard P, Nehme-Schuster H, Simler JM, Finck G, Baumann R, Pasquali JL. Videocapsule endoscopy is useful for the diagnosis of intestinal lymphangiectasia. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:699-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tift WL, Lloyd JK. Intestinal lymphangiectasia. Long-term results with MCT diet. Arch Dis Child. 1975;50:269-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee HL, Han DS, Kim JB, Jeon YC, Sohn JH, Hahm JS. Successful treatment of protein-losing enteropathy induced by intestinal lymphangiectasia in a liver cirrhosis patient with octreotide: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:466-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kondo M, Bamba T, Hosokawa K, Hosoda S, Kawai K, Masuda M. Tissue plasminogen activator in the pathogenesis of protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:1045-1047. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Fleisher TA, Strober W, Muchmore AV, Broder S, Krawitt EL, Waldmann TA. Corticosteroid-responsive intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to an inflammatory process. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:605-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Homan M, Tsimogiannis K S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Zhang DN