Published online Jul 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8256

Peer-review started: January 14, 2015

First decision: April 13, 2015

Revised: April 29, 2015

Accepted: May 21, 2015

Article in press: May 21, 2015

Published online: July 21, 2015

Processing time: 189 Days and 21.3 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification has been endorsed as the optimal staging system and treatment algorithm for HCC by the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. However, in real life, the majority of patients who are not considered ideal candidates based on the BCLC guideline still were performed hepatic resection nowadays, which means many hepatic surgeons all around the world do not follow the BCLC guidelines. The accuracy and application of the BCLC classification has constantly been challenged by many clinicians. From the surgeons’ perspectives, we herein put forward some comments on the BCLC classification concerning subjectivity of the assessment criteria, comprehensiveness of the staging definition and accuracy of the therapeutic recommendations. We hope to further discuss with peers and colleagues with the aim to make the BCLC classification more applicable to clinical practice in the future.

Core tip: The accuracy and application of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification for hepatocellular carcinoma has constantly been challenged by many clinicians. From the surgeons’ perspectives, we herein put forward some comments with an aim to make the BCLC classification more applicable to clinical practice in the future.

- Citation: Yang T, Lau WY, Zhang H, Huang B, Lu JH, Wu MC. Grey zone in the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Classification for hepatocellular carcinoma: Surgeons’ perspective. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(27): 8256-8261

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i27/8256.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8256

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1,2]. As HCC is usually associated with cirrhosis, the treatment is complex because of the need to be oncologically radical but liver parenchymal-destruction conservative[3]. Potentially curative treatments for HCC include liver resection, transplantation, or local ablative therapy[4].

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification[5] has been endorsed as the optimal staging system and treatment algorithm for HCC by the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD)[6,7]. The main prognostic factors of this staging system are related to tumor status (defined by the number and size of nodules, the presence or absence of vascular invasion and the presence or absence of extrahepatic spread), liver function (defined by the Child-Pugh classification and portal hypertension), and general performance status defined by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG). The BCLC classification links stage stratification with corresponding therapeutic recommendations, with liver resection recommended only to those patients harboring early-stage tumors (BCLC Stage A)[1,5,7]. However, a recent study published in Ann Surg[8] disclosed that in ten well-known hepatobiliary tertiary referral centers in the West and the East, 50% of patients harboring intermediate or advanced HCC still underwent surgery despite the BCLC guidelines recommend palliative treatments (chemoembolization or oral sorafenib). As liver surgeons, we would like to raise the following comments, which need to be discussed with and further clarified by the BCLC constitutors.

First, judgment subjectivity exists in the BCLC classification to some extent, which takes root in the assessment of the ECOG PS itself (an important prognostic factor in this classification). According to the definition of the BCLC classification, patients with advanced HCC (i.e., BCLC stage C) include patients with cancer-related symptoms (PS 1-2), vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, or a combination[1]. In other words, once the HCC patients have cancer-related symptoms (PS 1 means still near fully ambulatory and PS 2 means less than 50%[9]), they should be classified as advanced HCC (i.e., BCLC stage C). However, it is often difficult to judge whether atypical symptoms such as abdominal pain or malaise, are tumor-related or liver-related, as more than half of patients with HCC have cirrhosis at diagnosis. Actually, biases by physicians on subjective evaluation commonly exist in clinical practice, especially for those patients with a single HCC but with compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A).

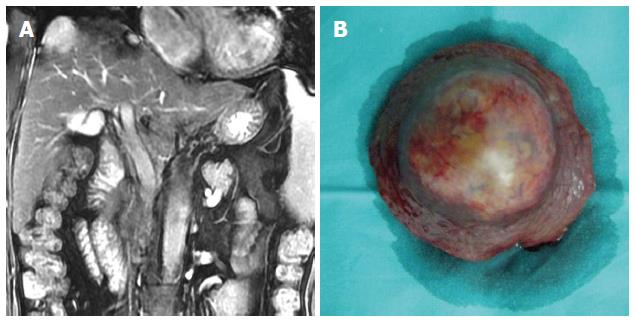

In our opinion, even if the patient’s symptoms are definitely tumor-related (i.e., PS 1-2), the diagnosis of advanced HCC in the BCLC classification is debatable. A female patient who complained of persistent right epigastric pain was diagnosed to harbor a single 3-cm HCC with compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A). Her persistent abdominal pain (PS 2) was caused by an exophytic tumor growth compressing on the diaphragm (Figure 1). According to the BCLC classification, she had a BCLC stage C HCC. According to the BCLC guidelines, only oral sorafenib should be given. In actual fact curative HCC resection was successfully performed for this patient in August 2007, and she is still alive and disease-free.

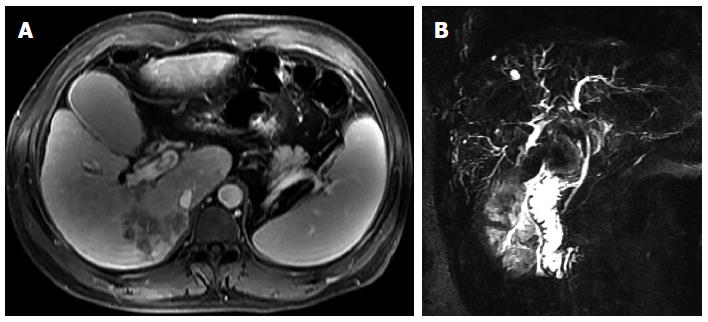

Additionally, although the BCLC constitutors tried very hard to take every possible situation into consideration, the truth is that in many HCC patients the situation is more complicated. For example, the BCLC classification gave full consideration of the presence of vascular invasion as an independent poor prognostic factor of HCC, but it never mentioned the presence of biliary invasion (Figure 2), which is a specific but not an uncommon type of HCC[10]. Previous studies has shown that the prognosis of HCC with biliary invasion with or without obstructive jaundice is as poor as HCC with vascular invasion despite treatment[11-13]. Should biliary invasion be included into the BCLC staging just like vascular invasion? It may be still a blind spot by the BCLC classification[14].

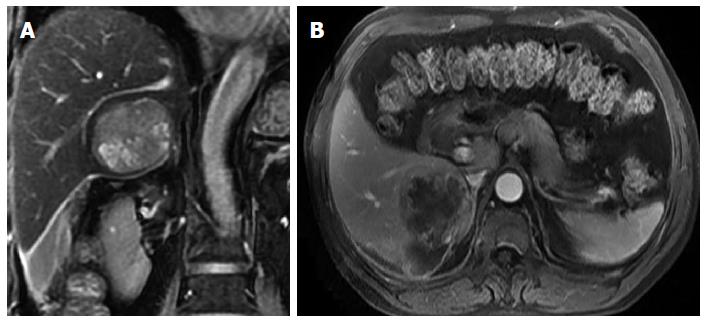

Another specific group of HCC patients who have never been mentioned in the BCLC classification is ruptured HCC (Figure 3), which happens in about 3%-15% of patients with HCC[15-18]. Once a patient develops acute spontaneous rupture of HCC (mostly PS 3-4 as a life-threatening complication), the patient should be classified according to the BCLC classification as having a terminal stage HCC (i.e., BCLC stage D). Should only supportive care be given to these patients in accordance with the BCLC guidelines? In numerous previously published studies, emergency transarterial embolization or liver resection (either emergency or staged) have been performed on these patients, and satisfactory results have been obtained, including saving lives in acute emergencies and even having occasional patients with long-term survival[15,16,18-22]. Thus, in our opinions, it is necessary for the BCLC classification to clarify this special but not uncommon situation of HCC so as to avoid some clinicians blindly adhering to the treatment guidelines.

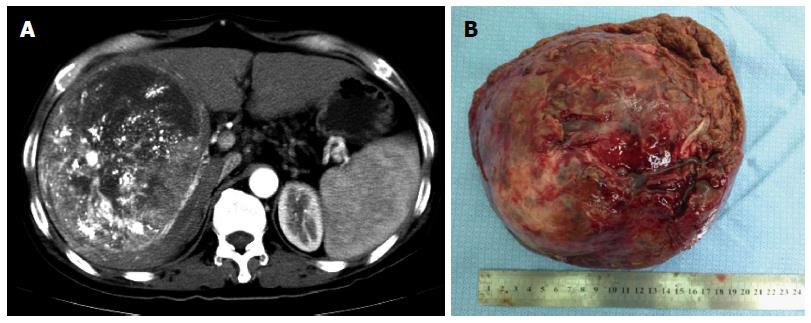

For most liver surgeons, it is not surprising that the authors of the recent study[8] stated that the BCLC treatment recommendation concerning surgery for HCC was too restrictive, and the authors suggested updating the EASL/AALSD therapeutic guidelines. However, in two subsequent correspondences[23,24], Dr. Bruix (one of the BCLC constitutors) and other renowned scholars pointed out the misclassification between the BCLC stage A and B for some patients in the study. In the subsequent replies[25,26] by the authors, a large number of articles released by the BCLC constitutors[1,5-7,27-32] were listed which clearly indicated 5 cm was used as a cutoff point between the BCLC stages A and B (intermediate), and the variable of size was included as a criterion for the differentiation between these two stages (Figure 4A). Beyond any doubt, this is a high-level debate in academic circles because most of these participating scholars have published hundreds of academic papers in the field of HCC. What is worth reflecting on is why such a controversy on the BCLC classification should still exist among these top experts in HCC. Would it be even more confusing for the majority of ordinary clinicians? It seems incredible to us that this recent debate on which BCLC stage should a patient with HCC belong to is still on-going, as the BCLC classification has been proposed for 15 years[5] and it has passed through several sequential revisions[1,32,33].

Undoubtedly, HCC is one of the most complicated and heterogeneous disease which requires multidisciplinary management by a team of hepatologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, oncologists, pathologists, and nurses. The purpose of formulation of a staging system is to provide accurate information for easy classification of patients into different risk groups. A precise staging helps to make therapeutic decisions and to estimate prognosis. Unfortunately, the best tool for staging HCC remains controversial. The lack of a consensus on an HCC staging system is mostly in part related to the heterogeneity in treatment modalities at diagnosis[34]. Therefore, as we think, it is necessary to establish specific HCC staging systems to assess prognosis, directed toward different treatment modalities, for example, for those patients with resectable or non-resectable HCC[35,36]. Considering the most complexities of HCC treatment among all malignancies, it was inadvisable and impractical to try conducting a specific or sole treatment modality for all HCCs by using a seemingly simple but uniform treatment algorithm just like the current BCLC guideline, which may well do more than good in the real life. Therefore, this should be the major intrinsic limitation of the BCLC classification, since this so-called “authoritative guidance” attempts generalize all probabilities of the treatment for patients with HCC.

In addition, it should be noted that only surgery, radiofrequency ablation, TACE, oral sorafenib, and symptomatic treatment were recommended in the BCLC guideline, but many other effective or promising treatment modalities for HCC have never been mentioned by the BCLC treatment schedule, such as radiotherapy, Yttrium (90) radioembolization, cryotherapy, microwave coagulation therapy, laser therapy, traditional Chinese medicine, immunotherapy, and so on[37-41]. Therefore, it should be considered as biased and insufficient for the BCLC treatment guideline, which may also need to be further modified by the BCLC conductors in the future.

It’s worth mentioning that nowadays the majority of patients who are not considered ideal candidates based on the BCLC guideline still agree to undergo hepatic resection all around the world[8,42,43]. An international multicenter study by Roayaie et al[42] which reported a 5-year overall survival rate of > 30% in the candidates based on the current guidelines for HCC. This group of patients accounted for nearly 70% of all the patients who underwent hepatic resection during the study period. These figures tell us currently there are many hepatic surgeons who do not follow the guidelines for HCC according to the BCLC recommendation[44-46]. Are these surgeons irresponsible? Or have patients been misled by these surgeons to make a wrong decision?

The superiority of the BCLC classification, when compared with other existing staging systems, is to provide treatment recommendations based on different stages of HCC. However, the validity of some of these recommendations requires further verification, since most of them are based on observational studies. Till now, there is still a lack of good high-level evidences in the field of HCC treatment (only fewer than one hundred RCTs on HCC have been published in the medical literature)[27]. Therefore, more clinical evidences need to be created and accumulated in the future. Admittedly, the evidences coming from RCTs are more reliable and valuable than those coming from retrospective or prospective cohort studies, although it is not desirable to underestimate, or even deny, the true value of the latter types of studies. We should also recognize that it is difficult, sometimes even impossible to conduct a RCT, especially those involving surgery, as funding support for a surgical research is always the biggest obstacle compared with a new drug research. Adding to the complexity on therapeutic researches on HCC, whether multidisciplinary treatment is better than singly therapy, and whether personalized therapy would produce better results to an individual patient with HCC are questions which have not been answered.

As Dr. Bruix[1] said, further refinement is still needed for the BCLC classification. We herein bring up our doubts and confusions about the BCLC classification. We hope to further discuss with peers and colleagues with an aim to make the BCLC classification more applicable to clinical practice in the future.

| 1. | Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3249] [Cited by in RCA: 3630] [Article Influence: 259.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 2. | Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8789] [Cited by in RCA: 9588] [Article Influence: 799.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2881] [Cited by in RCA: 3130] [Article Influence: 208.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maluccio M, Covey A. Recent progress in understanding, diagnosing, and treating hepatocellular carcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:394-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 703] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2645] [Cited by in RCA: 2918] [Article Influence: 108.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421-430. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6631] [Article Influence: 442.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations?: an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg. 2013;257:929-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Sørensen JB, Klee M, Palshof T, Hansen HH. Performance status assessment in cancer patients. An inter-observer variability study. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:773-775. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ikenaga N, Chijiiwa K, Otani K, Ohuchida J, Uchiyama S, Kondo K. Clinicopathologic characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct invasion. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:492-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qin LX, Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:385-391. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lai EC, Lau WY. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with obstructive jaundice. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lau WY, Leung JW, Li AK. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as obstructive jaundice. Am J Surg. 1990;160:280-282. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yang T, Lin C, Zhai J, Shi S, Zhu M, Zhu N, Lu JH, Yang GS, Wu MC. Surgical resection for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1121-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Lai EC, Lau WY. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Surg. 2006;141:191-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Tso WK, Poon RT, Lam CM, Wong J. Management of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: single-center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3725-3732. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yeh CN, Lee WC, Jeng LB, Chen MF, Yu MC. Spontaneous tumour rupture and prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1125-1129. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Buczkowski AK, Kim PT, Ho SG, Schaeffer DF, Lee SI, Owen DA, Weiss AH, Chung SW, Scudamore CH. Multidisciplinary management of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:379-386. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lai EC, Wu KM, Choi TK, Fan ST, Wong J. Spontaneous ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. An appraisal of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1989;210:24-28. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Leung KL, Lau WY, Lai PB, Yiu RY, Meng WC, Leow CK. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: conservative management and selective intervention. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1103-1107. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Yang T, Sun YF, Zhang J, Lau WY, Lai EC, Lu JH, Shen F, Wu MC. Partial hepatectomy for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1071-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shimada R, Imamura H, Makuuchi M, Soeda J, Kobayashi A, Noike T, Miyagawa S, Kawasaki S. Staged hepatectomy after emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 1998;124:526-535. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Mazzaferro V, Roayaie S, Poon R, Majno PE. Dissecting EASL/AASLD Recommendations With a More Careful Knife: A Comment on “Surgical Misinterpretation” of the BCLC Staging System. Ann Surg. 2015;262:e17-e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bruix J, Fuster J. A Snapshot of the Effective Indications and Results of Surgery for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Tertiary Referral Centers: Is It Adherent to the EASL/AASLD Recommendations? An Observational Study of the HCC East-West Study Group. Ann Surg. 2015;262:e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M. Reply to Letter: “Dissecting EASL/AASLD Recommendations With a More Careful Knife: A Comment on ‘Surgical Misinterpretation’ of the BCLC Staging System”: Real Misinterpretation or Lack of Clarity Within the BCLC? Ann Surg. 2015;262:e18-e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M. Reply to Letter: “A Snapshot of the Effective Indications and Results of Surgery for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Tertiary Referral Centers: Is It Adherent to the EASL/AASLD Recommendations? An Observational Study of the HCC East-West Study Group”: When the Study Setting “Ignores” the Patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262:e30-e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208-1236. [PubMed] |

| 28. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4059] [Cited by in RCA: 4563] [Article Influence: 325.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 29. | List MA, D’Antonio LL, Cella DF, Siston A, Mumby P, Haraf D, Vokes E. The Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck Scale. A study of utility and validity. Cancer. 1996;77:2294-2301. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:519-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in RCA: 857] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bruix J, Llovet JM. Major achievements in hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2009;373:614-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S75-S87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Forner A, Reig ME, de Lope CR, Bruix J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: the BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:61-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 764] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 54.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen CH, Hu FC, Huang GT, Lee PH, Tsang YM, Cheng AL, Chen DS, Wang JD, Sheu JC. Applicability of staging systems for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma is dependent on treatment method--analysis of 2010 Taiwanese patients. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1630-1639. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Yang T, Zhang J, Lu JH, Yang LQ, Yang GS, Wu MC, Yu WF. A new staging system for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with six existing staging systems in a large Chinese cohort. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:739-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | op den Winkel M, Nagel D, Sappl J, op den Winkel P, Lamerz R, Zech CJ, Straub G, Nickel T, Rentsch M, Stieber P. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Validation and ranking of established staging-systems in a large western HCC-cohort. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Tsang FH, Wong J. Locoregional therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: a critical review from the surgeon’s perspective. Ann Surg. 2002;235:466-486. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Poon D, Anderson BO, Chen LT, Tanaka K, Lau WY, Van Cutsem E, Singh H, Chow WC, Ooi LL, Chow P. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian Oncology Summit 2009. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1111-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wu MC. [Traditional Chinese medicine in prevention and treatment of liver cancer: function, status and existed problems]. Zhongxiyi Jiehe Xuebao. 2003;1:163-164. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Zhai XF, Chen Z, Li B, Shen F, Fan J, Zhou WP, Yang YK, Xu J, Qin X, Li LQ. Traditional herbal medicine in preventing recurrence after resection of small hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Integr Med. 2013;11:90-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Greten TF, Wang XW, Korangy F. Current concepts of immune based treatments for patients with HCC: from basic science to novel treatment approaches. Gut. 2015;64:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Roayaie S, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Park JW, Yang J, Yan L, Schwartz M, Han G, Izzo F, Chen M. The role of hepatic resection in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, Trevisani F, Farinati F, Spolverato G, Volk M, Giannini EG, Ciccarese F, Piscaglia F. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kokudo N. Is it a time to modify the BCLC guidelines in terms of the role of surgery? World J Surg. 2015;39:469-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhong JH, Ke Y, Gong WF, Xiang BD, Ma L, Ye XP, Peng T, Xie GS, Li LQ. Hepatic resection associated with good survival for selected patients with intermediate and advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2014;260:329-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Conci S, Valdegamberi A, Vitali M, Bertuzzo F, De Angelis M, Mantovani G, Iacono C. Hepatocellular carcinoma: surgical perspectives beyond the barcelona clinic liver cancer recommendations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7525-7533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Schmidt L, Ling CQ S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM