Published online Jun 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7577

Peer-review started: May 30, 2014

First decision: June 18, 2014

Revised: September 19, 2014

Accepted: January 21, 2015

Article in press: January 22, 2015

Published online: June 28, 2015

Processing time: 395 Days and 22.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate the efficacy and safety profile of pancreatic duct (PD) stent placement for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP).

METHODS: We performed a search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library to identify randomized controlled clinical trials of prophylactic PD stent placement after ERCP. RevMan 5 software provided by Cochrane was used for the heterogeneity and efficacy analyses, and a meta-analysis was performed for the data that showed homogeneity. Categorical data are presented as relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and measurement data are presented as weighted mean differences and 95%CIs.

RESULTS: The incidence rates of severe pancreatitis, operation failure, complications and patient pain severity were analyzed. Data on pancreatitis incidence were reported in 14 of 15 trials. There was no significant heterogeneity between the trials (I2 = 0%, P = 0.93). In the stent group, 49 of the 1233 patients suffered from PEP, compared to 133 of the 1277 patients in the no-stent group. The results of this meta-analysis indicate that it may be possible to prevent PEP by placing a PD stent.

CONCLUSION: PD stent placement can reduce postoperative hyperamylasemia and might be an effective and safe option to prevent PEP if the operation indications are well controlled.

Core tip: Pancreatitis is one of the most common and severe complications after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The reported incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) varies between 2% and 7% in prospective trials and may be as high as 30%-50% in high-risk patients. Although a previous meta-analysis has indicated that pancreatic duct stent placement can prevent PEP, particularly in high-risk patients, there is a lack of high-quality evidence-based studies based on appropriate numbers of well-validated publications. Therefore, an updated meta-analysis was conducted to investigate stents in preventing PEP.

- Citation: Fan JH, Qian JB, Wang YM, Shi RH, Zhao CJ. Updated meta-analysis of pancreatic stent placement in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(24): 7577-7583

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i24/7577.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7577

Pancreatitis is one of the most common and severe complications after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The reported incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) varies between 2% and 7% in prospective trials of non-selective studies[1-4] but may be as high as 30%-50% in high-risk patients. Andriullin et al[5] studied 16855 patients who underwent ERCP between 1977 and 2006 and found that the incidence of PEP was 3.47% (585 patients). Although most patients experienced mild PEP, 10% of patients developed severe PEP, which led to prolonged hospital stays, increased medical costs, and life threatening symptoms[6].

The precise mechanisms of PEP remain unclear. It was demonstrated by Chahal et al[7] that a substitute drainage pathway could prevent PEP, confirming the hypothesis that pancreatic drainage blockage as a result of Oddi sphincter spasms or papillary edema might be a major reason for PEP. Therefore, it is reasonable that pancreatic stent placement could improve pancreatic drainage and reduce the enzymatic reactions of tryptic enzymes.

Although a previous meta-analysis[8] has indicated that PD stent placement can prevent PEP, particularly in high-risk patients, there is a lack of high-quality evidence-based studies based on appropriate numbers of well-validated publications. For instance, low-quality retrospective studies were retrieved for a meta-analysis conducted by Singh et al[9], which might have led to a less confident conclusion. Another example is a study by Pan et al[10]; although it included six retrospective clinical trials, only abstracts were available for three of these studies. In addition, because of the limitations of the literature, the incidence rates of PEP and severe PEP from PD stent placement require a specific technique due to the unique anatomical structure of the pancreas duct. PD stenting might increase post-ECRP complications if there are any manipulation accidents during placement. Therefore, safety remains an important concern during prophylactic PD stent placement. Here, we analyzed the efficacy and safety of PD stent placement to prevent PEP by performing a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies.

We retrieved randomized controlled clinical trials of PD stent placement that were published in English or Chinese and contained full texts or abstracts. Patients who underwent prophylactic PD stent placement were included in a PD stent group, and patients who did not undergo stent placement were included in a control group. The medication strategies were not included in the analysis.

The clinical trials with pre-operative PD stents were excluded, as were publications with incomplete datasets or repeated data.

Published clinical trials on prophylactic PD stents to prevent PEP were retrieved from MEDLINE (between 1980 and May 2013), EMBASE (between 1980 and May 2013), and Cochrane clinical trial databases. Using PubMed as an example, the retrieval strategy included the keyword, subject heading, or the combination, such as “pancreatic* AND stent* AND (ERCP OR Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) AND (PEP OR pancreatitis).”

The full-text publications were read, and relevant information was independently extracted by two researchers. The assessments included the risk of bias, information integrity, selectiveness, and other potential biases. When a discrepancy occurred between the two researchers with regard to the extracted information or the publication quality, the original publications were re-reviewed until an agreement was achieved. Because of the difficulties of PD stent placement, most of the studies did not include a sham group. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis of the surgery outcome was conducted instead of an evaluation on blindness grouping.

RevMan 5 software provided by Cochrane was used for the heterogeneity and efficacy analyses, and a meta-analysis was performed for the data that showed homogeneity. Categorical data are presented as relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs), and measurement data are presented as weighted mean differences (WMDs) and 95%CIs. The differences among the published studies were analyzed using the χ2 test (P < 0.1 as a test level), and I2 was used to determine the significance of the difference (I2 > 50% indicated significant or substantial differences; I2 > 75% indicated no need for a merged analysis). The fixed-coefficient model was used if there were no significant differences; otherwise, the random coefficient model was used. Descriptive analyses were performed for data that could not be used for the merged analysis. If there was statistical significance between the PD stent and control groups in terms of PEP prevention by meta-analysis, a funnel plot was used for bias analysis.

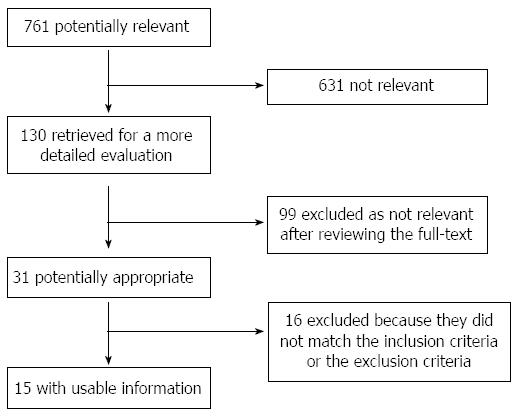

The flow chart in Figure 1 depicts the publication retrieval process.

Of the 15 studies published between 1990 and 2013, 12 were published articles and 3 were abstracts (Table 1). All the studies included various high-risk groups, such as patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunctions (SODs), difficult cannulation, pre-cut sphincterotomy, pancreatic sphincterotomy, biliary balloon dilation of intact papilla for stone extraction, endoscopic ampullectomy, and pancreatic brush cytology.

| Ref. | Type | Study type | Intervention | Stent | Patients | n (stent) | n (control) |

| Smithline et al[16], 1993 | Article | RCT | Biliary ES | 5-7F, 2-2.5 cm | SOD | 43 | 50 |

| Sherman et al[17], 1996 | Abstract | RCT | Precut biliary ES | 5-7F, 2-2.5 cm | 46 | 58 | |

| Tarnasky et al[12], 1998 | Article | RCT | Biliary ES | 5-7F, 2-2.5 cm | SOD | 41 | 39 |

| Tarnasky et al[12], 1998 | Abstract | RCT | Biliary ES | 5F, 2 cm | 36 | 38 | |

| Patel et al[18], 1999 | Abstract | RCT | Pancreatic ES | 5-7F, 2-2.5 cm | SOD | 18 | 18 |

| Fazel et al[19], 2003 | Article | RCT | ERCP | 5F, 2 cm | Difficult cannulation | 38 | 36 |

| Harewood et al[20], 2005 | Article | RCT | Endoscopic ampullectomy | 5F, 3-5 cm | Ampullary adenoma | 11 | 8 |

| Sofuni et al[21], 2007 | Article | RCT | ERCP, etc. | 5F, 3 cm | Various | 98 | 103 |

| Tsuchiya et al[22], 2007 | Article | RCT | ERCP, etc. | 5F, 3-4 cm | Various | 32 | 32 |

| Ito et al[23], 2010 | Article | RCT | ES, IDUS | 5F, 4 cm | With high-risk factors | 35 | 35 |

| Pan et al[24], 2011 | Article | RCT | ERCP | 5F | With high-risk factors | 20 | 20 |

| Sofuni et al[25], 2011 | Article | RCT | ERCP, etc. | 5F, 3 cm | With high-risk factors | 213 | 213 |

| Kawaguchi et al[26], 2012 | Article | RCT | ERCP, ES, IDUS | 5F, 3 cm | With high-risk factors | 60 | 60 |

| Cha et al[27], 2012 | Article | RCT | ES | 5-7F, 2-2.5 cm | Difficult cannulation | 46 | 58 |

| Lee et al[28], 2012 | Article | RCT | ES, IDUS, etc. | 3, 4, 6, 8F | Difficult cannulation | 50 | 51 |

The conditions of randomization, double-blinding, and the risk of missing data from each study were evaluated. Nine studies reported randomization concealment, but none of the studies were double-blinded. Half of the studies used statistics from the intent-to-treat group, and the other half assessed the loss of data. The results are shown in Table 2.

| Ref. | Concealment of randomization | Double-blinding | Risk of losing data |

| Smithline et al[16], 1993 | - | - | - |

| Sherman et al[17], 1996 | - | - | NK |

| Tarnasky et al[12], 1998 | + | - | NK |

| Patel et al[18], 1999 | - | - | NK |

| Fazel et al[19], 2003 | + | - | + |

| Harewood et al[20], 2005 | + | - | + |

| Sofuni et al[21], 2007 | + | - | + |

| Tsuchiya et al[22], 2007 | + | - | - |

| Ito et al[23], 2010 | + | - | - |

| Pan et al[24], 2011 | - | - | - |

| Sofuni et al[25], 2011 | + | - | - |

| Kawaguchi et al[26], 2012 | + | - | - |

| Cha et al[27], 2012 | - | - | - |

| Lee et al[28], 2012 | + | - | - |

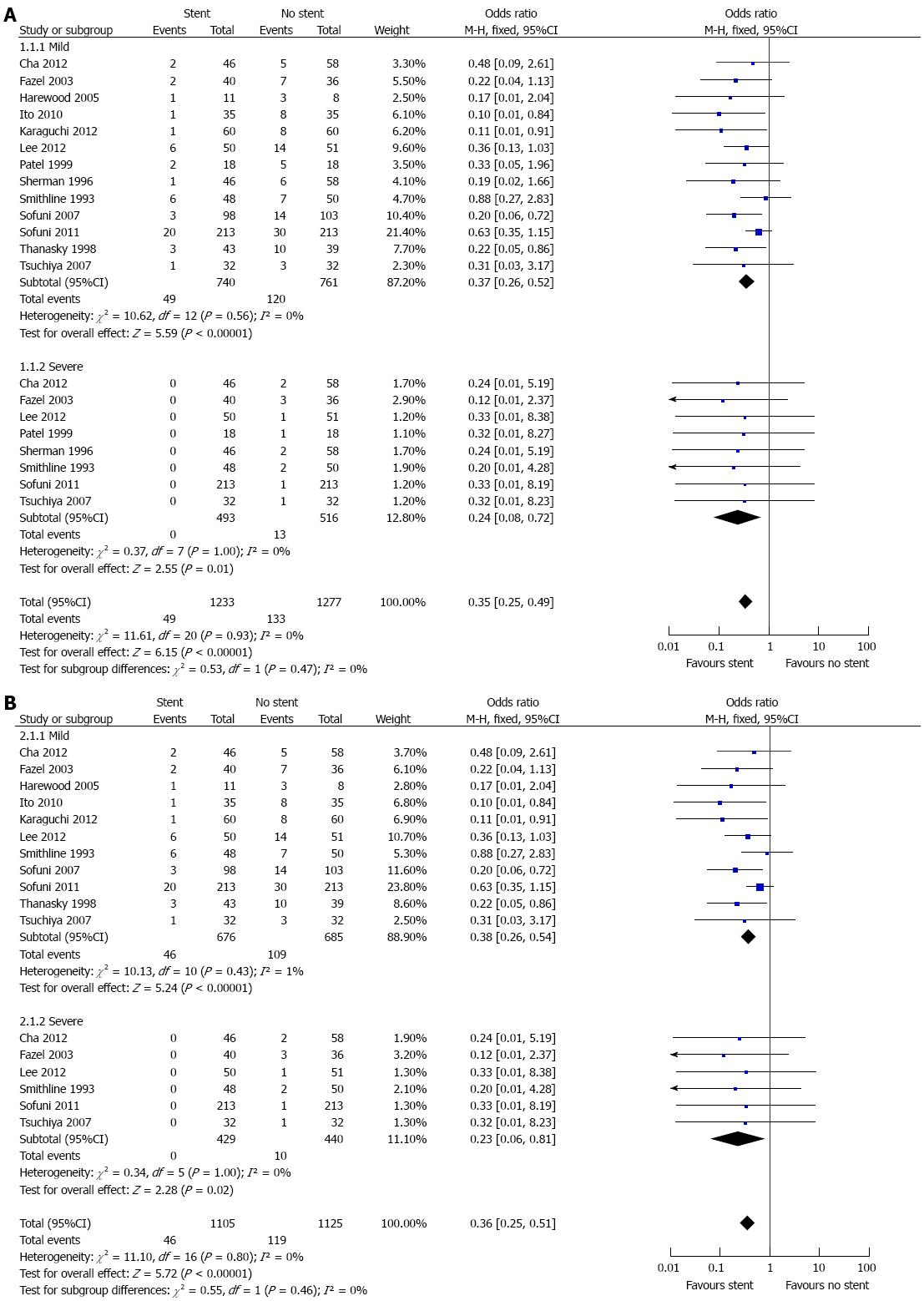

Data on pancreatitis incidence were reported in 14 (12 in articles and 2 in abstracts) of 15 trials. There was no significant heterogeneity between the trials (I2 = 0%, P = 0.93); therefore, a fixed effects model was used to pool the results. In the stent group, 49 of the 1233 patients suffered from PEP, compared to 133 of 1277 patients in the no-stent group. The meta-analysis (Figure 2) showed that the stent group had a significantly (P < 0.00001) lower incidence of PEP (OR = 0.35; 95%CI: 0.25-0.49). Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the incidence of different degrees of PEP. These results are shown in Figure 2A. Because the data from the abstracts were not comprehensive, which may lead to bias and affect the reliability of the results, we also conducted an analysis in which data from abstracts were excluded (Figure 2B). The results (OR = 0.36; 95%CI: 0.25-0.51, P < 0.00001) showed no significant difference from the pooled results that included all the data.

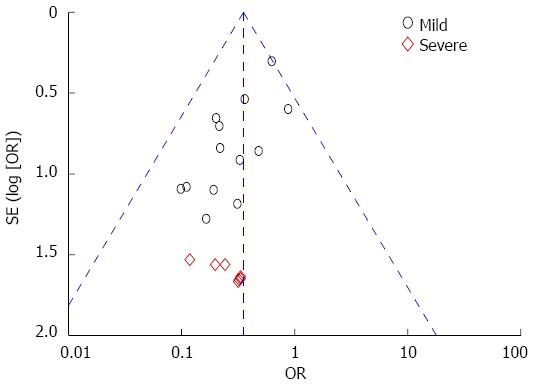

Possible publication bias was assessed using Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test. No evidence of publication bias was detected (Figure 3).

Each study was excluded from the analysis one by one to assess how its exclusion would affect the pooled estimate. Our results for PEP incidence in the entire study and each subgroup were robust.

Papillary balloon dilation, incision, and pre-incision are usually required during diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP operations. Surgical manipulation in combination with concurrent superoxide dismutase disease can result in pancreatic duct drainage blockage and intracellular proteolytic enzyme activation[11]. Bacterial contamination during endoscopic surgery can result in chemical or allergic injuries to the pancreas and subsequent local inflammatory cascading, which can eventually lead to pancreatitis. PEP is one of the most common and severe complications after ERCP, and effective prophylactic intervention is of great clinical significance. Tarnasky et al[12] found that patients with accessory papilla usually had a lower PEP incidence when the pancreatic papilla was blocked, indicating that improved pancreatic drainage might effectively decrease the incidence of PEP. In addition, Bourke et al[13] reported that although the incidence of pancreatitis after sphincterotomy was higher than that after diagnostic ERCP, the rate of severe PEP was significantly reduced, implying that sphincterotomy might be able to reduce PEP severity. Because PD stent placement can prevent pancreatic duct drainage impairment as a result of papillary edema or sphincter spasms, it might be an effective option to prevent PEP.

All the 15 published studies used in the current analysis were RCTs and included 1606 patients, making this analysis larger than a previous similar study. We also analyzed the association between PD stent length and PEP occurrence. Therefore, our study had more validated methods and comprehensive data compared to the previous publication. PEP risk factors include difficulty with intubation, sphincter pre-incision, pancreatic duct opacification, and a previous history of PEP. When there is difficulty in pancreatic duct intubation, pancreatic duct stent-assisted bile duct intubation, pancreatic duct guidewire-assisted bile duct intubation, or pre-incision technology is usually conducted to improve the success rate of bile duct intubation. The cases included in the current study were all cases with intubation difficulty; PD stent placement-assisted intubation was employed in the PD stent group, and if that failed, biliary duct deep intubation by fenestration was performed. Pancreatic duct guidewire-assisted bile duct intubation was conducted in the control group, but biliary duct deep intubation by fenestration was performed if the guidewire-assisted procedure failed. Our analysis showed that the proportions of bile duct deep intubation, pancreatic duct opacification, and pancreatic duct guidewire-assisted bile duct intubation were similar between the PD stent placement and control groups. It was reported by Fogel et al[14] that the pre-incision of the biliary sphincter combined with PD stent placement could improve the success rate of selective bile duct intubation and reduce the frequency of repeated intubation. Similarly, the success rate of selective bile duct intubation was 97.4% in a study by Goldberg et al[15], who used PD stent-assisted intubation and reported mild pancreatitis in just two patients, indicating a satisfactory safety profile of the technique. In the current study, there were 49 patients with mild PEP and no patients with severe PEP in the PD stent placement group compared to 120 and 13 patients in the control group, respectively. There was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of the incidence of complications.

Although pancreatic stenting decreases the incidence of PEP, potential problems remain that may cause PEP in the stent group. Stent placement following biliary interventions can be difficult. Failure usually occurs because the pancreatic orifice cannot be identified or a guidewire cannot be advanced deeply into the duct. Likewise, an additional endoscopy is often needed for stent removal.

In conclusion, the results of this meta-analysis indicate that it may be possible to prevent PEP by placing a PD stent. This procedure can reduce postoperative hyperamylasemia and might be an effective and safe option to prevent PEP if the operation indications are well controlled.

Pancreatitis is one of the most common and severe complications after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The reported incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) varies between 2% and 7% in prospective trials and may be as high as 30%-50% in high-risk patients.

The precise mechanisms of PEP remain unclear. It was demonstrated by Chahal et al that a substitute drainage pathway could prevent PEP, confirming the hypothesis that pancreatic drainage blockage as a result of Oddi sphincter spasms or papillary edema might be a major reason for PEP. Therefore, it is reasonable that pancreatic stent placement could improve pancreatic drainage and reduce the enzymatic reactions of tryptic enzymes. Although a previous meta-analysis has indicated that pancreatic duct (PD) stent placement can prevent PEP, particularly in high-risk patients, there is a lack of high-quality evidence-based studies based on appropriate numbers of well-validated publications.

All the 15 published studies used in the current analysis were randomized controlled trials and included 1606 patients, making this analysis larger than a previous similar study.

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that it may be possible to prevent PEP by placing a PD stent. This procedure can reduce postoperative hyperamylasemia and might be an effective and safe option to prevent PEP if the operation indications are well controlled.

The authors in this manuscript evaluate the existing literature on this topic. The quality standards for inclusion are high, and their methodology is sound. This is an interesting and valuable contribution.

| 1. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1704] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 617] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, Pilotto A, Forlano R. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1781-1788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in RCA: 804] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Abdel Aziz AM, Lehman GA. Pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2655-2668. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Chahal P, Tarnasky PR, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Gostout CJ, Baron TH. Short 5Fr vs long 3Fr pancreatic stents in patients at risk for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Mazaki T, Masuda H, Takayama T. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:842-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Singh V, Singh G, Verma GR, Gupta R. Endoscopic management of postcholecystectomy biliary leakage. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:409-413. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Pan T, Wang YP, Yang JL, Tian L, Li YD. Pancreatic Duct Stenting for Preventing Post-ERCP Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. Chin J Evidence-Based Med. 2004;4:693-699. |

| 11. | Bailey AA, Bourke MJ, Kaffes AJ, Byth K, Lee EY, Williams SJ. Needle-knife sphincterotomy: factors predicting its use and the relationship with post-ERCP pancreatitis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-1524. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bourke MJ, Costamagna G, Freeman ML. Biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: core technique and recent innovations. Endoscopy. 2009;41:612-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fogel EL, Sherman S, Bucksot L, Shelly L, Lehman GA. Effects of droperidol on the pancreatic and biliary sphincters. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:488-492. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Goldberg SL, Colombo A, Maiello L, Borrione M, Finci L, Almagor Y. Intracoronary stent insertion after balloon angioplasty of chronic total occlusions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:713-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Smithline A, Silverman W, Rogers D, Nisi R, Wiersema M, Jamidar P, Hawes R, Lehman G. Effect of prophylactic main pancreatic duct stenting on the incidence of biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy-induced pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:652-657. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sherman S, Bucksot EL, Esber E. Does leaving a main pancreatic duct stent in place reduce the incidence of precut biliary sphincterotomy-induced pancreatitis? Randomized prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:241. |

| 18. | Patel R, Tarnasky PR, Hennessy WS. Does stenting after pancreatic sphincterotomy reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with prior biliary sphincterotomy? Preliminary results of a prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:AB80. |

| 19. | Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, Meyerson SM, Geenen JE. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:291-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harewood GC, Pochron NL, Gostout CJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement for endoscopic snare excision of the duodenal ampulla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Itoi T, Katanuma A, Hisai H, Niido T, Toyota M, Fujii T, Harada Y, Takada T. Prophylaxis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis by an endoscopic pancreatic spontaneous dislodgement stent. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsuchiya T, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Kawai T, Moriyasu F. Temporary pancreatic stent to prevent post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a preliminary, single-center, randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T. Can pancreatic duct stenting prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients who undergo pancreatic duct guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation? A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pan XP, Dang T, Meng XM, Xue KC, Chang ZH, Zhang YP. Clinical study on the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis by pancreatic duct stenting. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Mukai T, Kawakami H, Irisawa A, Kubota K, Okaniwa S, Kikuyama M, Kutsumi H, Hanada K. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stents reduce the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:851-88; quiz e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa M, Omata F, Ito H, Shimosegawa T, Mine T. Randomized controlled trial of pancreatic stenting to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1635-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cha SW, Leung WD, Lehman GA, Watkins JL, McHenry L, Fogel EL, Sherman S. Does leaving a main pancreatic duct stent in place reduce the incidence of precut biliary sphincterotomy-associated pancreatitis? A randomized, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:209-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee TH, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Han SH, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Park SH, Kim SJ. Prophylactic temporary 3F pancreatic duct stent to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with a difficult biliary cannulation: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Bentrem D, Kulkarni GV, Sakai Y, Zerem E, Zhong YQ S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN