Published online Jun 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.7059

Peer-review started: January 8, 2015

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: March 9, 2015

Accepted: March 30, 2015

Article in press: March 31, 2015

Published online: June 14, 2015

Processing time: 161 Days and 23.2 Hours

Visceral myopathy is one of the causes of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Most cases pathologically reveal degenerative changes of myocytes or muscularis propia atrophy and fibrosis. Abnormal layering of muscularis propria is extremely rare. We report a case of a 9-mo-old Thai male baby who presented with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Histologic findings showed abnormal layering of small intestinal muscularis propria with an additional oblique layer and aberrant muscularization in serosa. The patient also had a short small bowel without malrotation, brachydactyly, and absence of the 2nd to 4th middle phalanges of both hands. The patient was treated with cisapride and combined parenteral and enteral nutritional support. He had gradual clinical improvement and gained body weight. Subsequently, the parenteral nutrition was discontinued. The previously reported cases are reviewed and discussed.

Core tip: This report describes the case of a 9-mo-old boy who presented with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Full-thickness small bowel biopsy showed abnormal layering of muscularis propria (additional oblique layer) and serosal aberrant muscularization. There have been only eight previously reported abnormal layering cases and only one case with an additional oblique layer. The patient also had a short small bowel without malrotation, brachydactyly, and absence of the 2nd to 4th middle phalanges of both hands. The patient showed clinical improvement with medical treatment and nutritional support.

- Citation: Angkathunyakul N, Treepongkaruna S, Molagool S, Ruangwattanapaisarn N. Abnormal layering of muscularis propria as a cause of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(22): 7059-7064

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i22/7059.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.7059

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) was first described by Dudley in 1958[1]. It is a rare, severe gastrointestinal disorder in which intestinal motility is impaired. CIPO can be congenital or acquired (primary or secondary)[2], and is characterized by recurrent signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction in the absence of true mechanical obstruction[3]. It can affect both adults and children. Most pediatric patients manifest at birth or in early infancy[4]. The two main pathophysiologic types of this motility disorder are myopathic and neuropathic[5]. This report describes a pediatric case of CIPO due to visceral myopathy with rare histology (abnormal layering muscularis propria and serosal aberrant muscularization) along with a review of the literature.

A 9-mo-old Thai male baby presented with abdominal distention and bilious vomiting that had begun at 2 wk of age. He could be fed orally and defecate daily. He was the first child with an uneventful history of prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal periods, and his birth weight was 3065 g. No family member had similar symptoms. He had visited another hospital at the age of 3 mo, and upper gastrointestinal studies were conducted revealing no intestinal malrotation or other gastrointestinal obstruction. His abdominal distention and bilious vomiting progressed and he had poor weight gain.

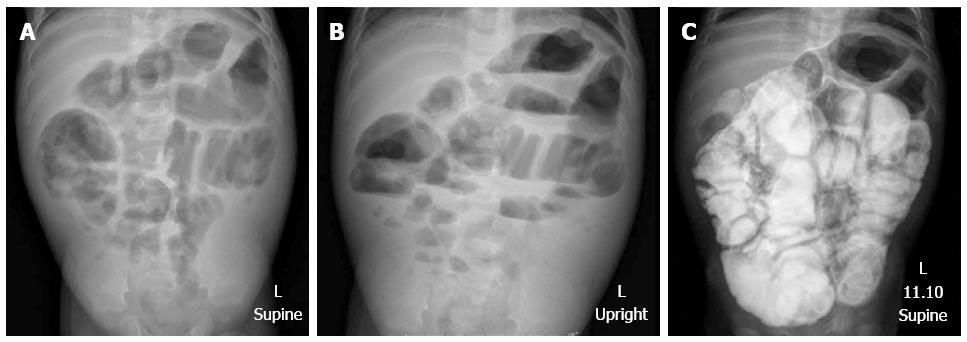

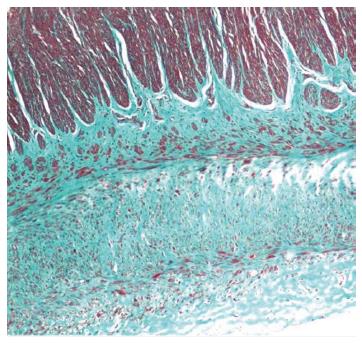

Upon presentation to our hospital, a physical examination showed a body weight of 5500 g (below the 3rd percentile), length 64 cm (10th percentile), no dysmorphic features, marked abdominal distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, visible peristalsis, and bilateral indirect inguinal hernia. He also had brachydactyly on both hands. X-ray film demonstrated an absence of middle phalanges of the 2nd to 4th fingers. The other systems were unremarkable. The plain abdominal radiographs showed diffuse small bowel dilatation (Figure 1). Barium enema showed no transitional zone or signs of Hirschsprung disease, but irregular mucosa of nearly his entire colon was noted. Small bowel follow-through showed dilatation with thickening fold of almost the entire small bowel from duodenum to ileum with hyperperistalsis, and partial distal small bowel obstruction was suspected (Figure 1). A bilateral inguinal hernia was suspected as the cause of partial gastrointestinal obstruction, and bilateral herniorrhaphy was performed. Unfortunately, his symptoms did not improve. Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy were performed to exclude mucosal diseases, and were unremarkable. The histology of biopsies from esophageal, duodenal, gastric, and colonic mucosa showed no significant pathologic findings or tissue eosinophilia. His clinical symptoms were worse with progressive bilious vomiting, abdominal distension, and poor weight gain. As intestinal obstruction could not be excluded, exploratory laparotomy was performed at the age of 9 mo. Intraoperative findings showed normal size of the colon, but thickening of the short small bowel, which measured 86 cm from the duodenojejunal junction to the ileocecal valve. A pale thickened and inflamed Tenia coli-like line was noted on the antimesenteric side from his duodenojejunal junction to 15 cm above the ileocecal valve (Figure 2). Appendectomy and full-thickness biopsy of the distal ileum were performed and sent for intraoperative consultation. The specimen was fixed in formalin afterward.

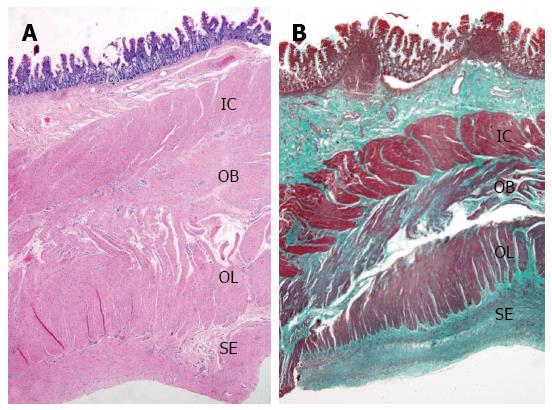

Full-thickness biopsy of the terminal ileum revealed unremarkable mucosa with no significant tissue eosinophilia. The submucosa showed hyalinization and fibrosis. Unremarkable ganglion cells in the submucosa (Henle’s) and deep submucosa (Meissner’s) were identified. Muscularis propria was markedly thickened and revealed abnormal layering into three layers; (1) inner circular; (2) additional oblique; and (3) outer longitudinal layer (Figure 3A). No degenerative change of myocyte (e.g., cytoplasmic vacuolation, variation in muscle fiber size, nuclear pleomorphism) or increased mitosis was observed. Periodic acid-Schiff staining revealed no intracytoplasmic inclusion. Diffuse delicate interstitial fibrosis in all muscular layers highlighted by Masson’s trichrome stain was noted (Figure 3B). Meissner’s plexuses were located between the inner circular and additional oblique layers. There was no inflammation in muscular layers or around ganglion cells or neural plexuses. The serosa showed three bizarre layers of aberrant muscularization and diffuse interstitial fibrosis into smooth muscles, grossly forming a Tenia coli-like line. Congo red stain excluded amyloidosis (Figure 4).

Sections of vermiform appendix showed unremarkable mucosal, mural, and serosal layers.

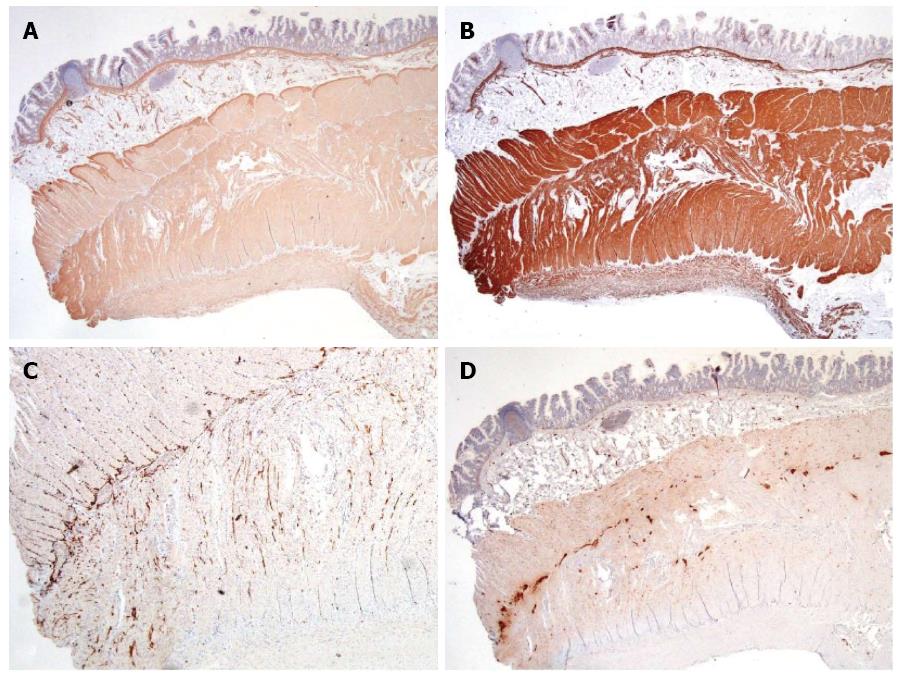

Muscularis mucosae, all muscular layers in muscularis propria, and serosa showed diffusely strong expression of smooth-muscle actin, desmin, and muscle actin. (Figure 5). S100 highlighted normal distribution of Henle’s, Meissner’s, and Auerbach’s neural plexuses with unremarkable ganglion cells. Normal expression of Bcl-2 was observed in all plexuses. Immunohistochemistry for CD117 revealed normal interstitial cells of Cajal networks around Auerbach’s plexus and extending to inner circular and outer longitudinal muscular layers. Thus, neuropathic and interstitial cells of Cajal abnormalities were excluded.

This report describes a pediatric case of primary CIPO due to visceral myopathy from abnormal layering of muscularis propria. Clinical presentations were similar to most cases of CIPO. The symptoms begin at birth in 50% of patients, and by age one year in 75%. Bilious vomiting, abdominal distension, and obstipation are almost universal presentations[6]. The majority of the pediatric cases are primary or idiopathic CIPO. Antonucci et al[7] identified secondary causes, such as organic, systemic, or metabolic causes, in only 4/77 CIPO patients. Antroduodenal manometry is useful for differentiating between the neuropathy and myopathy type[8]. Unfortunately, this investigation is not available in our institute. Definite diagnosis of CIPO requires full-thickness biopsies for histopathology.

Visceral myopathy can be divided into two groups. The first group is comprised of intrinsic myocyte defects with characteristic findings of vacuolar degeneration and fibrosis in inner circular and/or outer longitudinal muscular layers[9-12]. The other changes include nuclear atypia, increased mitotic activity, periodic acid-Schiff-positive intracytoplasmic inclusions[13], and absence or decreased smooth-muscle α-actin immunostaining in the circular muscle layer[14]. The second group comprises morphogenic abnormalities of muscularis propria. Most cases are of an atrophic pattern[8,13,15]. A few cases of a hypertrophic pattern with hypertrophy of one or both layers have been reported[8,16-18]. The abnormal layering of muscularis propria is exceedingly rare, and only eight cases have been reported (Table 1).

| Case | Sex/age | Presenting symptom | Site | Muscularis propria pathology | Other GI abnormality | Other findings | Remark | Ref. | |

| Additional layer | Location | ||||||||

| 1 | M/11 d | CIPO | S | Oblique | External to OL | Short small intestine + malrotation | Sclerocornea, cryptorchidism, scoliosis, deformity of extremities | [19] | |

| 2 | M | CIPO | S and L | Circular | Between IC and OL | Short intestine + malrotation | Megacystis | X-linked | [9] |

| 3 | M | CIPO | S and L | Circular | Between IC and OL | Short intestine + malrotation | Megacystis | X-linked | [9] |

| 4 | M | CIPO | S and L | Circular | Between IC and OL | Short intestine + malrotation | Megacystis | X-linked | [9] |

| 5 | F | Constipation | L | Circular | Internal to IC | - | - | [9] | |

| 6 | F | Constipation | L | Circular | Internal to IC | - | Megaureter | [9] | |

| 7 | M/16 yr | Constipation | L | Circular | Internal to IC | - | Dysmorphic facies and toes, seizures, leukoencephalopathy, cataract | Clinically improved after surgery | [22] |

| 8 | M/birth | Respiratory problem | S | Circular | External to OL | Short small intestine + malrotation | Diaphragmatic defect, High-arched palate, ASD, ventriculomegaly, Subependymal heterotopias, arachnoid cyst, spina bifida, proximally placed thumbs | Dead | [22] |

| 9 | M/9 mo | CIPO | S | Oblique | Between IC and OL | Short small intestine | Brachydactyly, absent 2nd to 4th middle phalanges of both hands | Clinically improved by medication | Present case |

Most cases with abnormally layered muscularis propria are male. The clinical symptoms appear early in life and depend on the site of involvement. Patients with colonic involvement present with constipation, whereas small intestine involvement manifests as vomiting and abdominal distension. Additional circular muscle coats in various locations are the most common feature. Only one case with an additional oblique layer similar to our case was reported by Yamagiwa et al[19]. To our knowledge, serosal Tenia coli-like aberrant muscularization has never been described in the literature.

Common associated abnormalities are a short small intestine (mostly with malrotation)[4,20], urinary involvement, including megacystis and megaureter[21], and skeletal deformity (spine and extremities). To our knowledge, there has been no report of association with brachydactyly and absence of the middle phalangeal bones in visceral myopathy cases. Smith et al[9] suggested an X-linked mode of inheritance in three related boys with abnormal layered muscularis propria of small and large intestines with megacystis. DNA analysis was not performed in our case due to unavailability in our institute.

The impact of abnormal layering of muscularis propria on the natural history or prognosis remains unknown as the numbers of cases are small. Among the eight reported cases, clinical outcome could be identified in only two cases. The first case had clinical improvement of constipation and grew into a healthy young man after partial resection of a dilated sigmoid colon and rectum. However, the second case died due to multiple organ anomalies[22].

There is no specific treatment for CIPO from visceral myopathy, and nutritional support is the mainstay of management in these children. Pharmacotherapy, including cisapride, erythromycin, and octreotide, to stimulate intestinal contractions, may be useful in some select cases[23,24]. Small bowel transplantation has a potential role for those who have irreversible intestinal failure and permanent dependence on parenteral nutrition[25,26]. Prognosis is fair to poor and a requirement for long-term parenteral nutrition is common in these patients[27]. A mortality rate of 25% has been reported in a large cohort study, and common causes of death are parenteral-related complications[21]. Our patient also had a short bowel accompanying the CIPO. Management modalities of short-bowel syndrome include enteral and parenteral nutritional support, treating small bowel bacterial overgrowth, and fish-oil-based lipid emulsions[28]. Currently, teduglutide, a recombinant analog of human glucagon-like peptide-2, is an emerging treatment for those with intestinal failure[29]. Our patient was treated with cisapride and combined parenteral and enteral nutritional support. He had gradual clinical improvement and gained body weight, and parenteral nutrition was subsequently discontinued. At the time of the writing of this report, he is 3 years-old and has normal growth, with a body weight of 15 kg (65th percentile) and height of 95 cm (55th percentile).

A 9-mo-old Thai male baby presented with abdominal distention that had been present since birth and bilious vomiting since 2 wk of age.

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

Hirschsprung’s disease.

Unremarkable findings for the laboratory tests.

Abdominal X-ray showed diffused dilatation of small bowel loops. Small bowel follow-through showed generalized bowel dilatation with thickening fold of entire small bowel loops from duodenum to ileum.

Full-thickness biopsy of ileum revealed abnormal layering of muscularis propria (additional oblique layer between inner circular and outer longitudinal layers) and serosal aberrant muscularization.

Medication (cisapride) and combined parenteral and enteral nutritional support.

There have been only eight previously reported abnormal layering cases, and only one case showed an additional oblique layer. The patient also had aberrant serosal muscularization, brachydactyly, and absence of 2nd to 4th middle phalanges in both hands, which have never been reported.

Abnormal layering of muscularis propria is an exceedingly rare condition of abnormal morphogenesis of muscularis propria (visceral myopathy), which causes chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

The case report presents the unique abnormal layering of muscularis propria and aberrant serosal muscularization in a case of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and different associated anomalies from previously reported cases. We learned that medical treatment and combined parenteral and enteral nutritional support improved clinical outcome.

The authors report an interesting case of a very rare situation presenting with intestinal pseudo-obstruction linked to a short small bowel and brachydactyly. In the gut, it was associated with an additional oblique muscle layer and with muscularization of the serosa. Although descriptive, this study also reviews the few cases described in the literature exhibiting visceral myopathy due to abnormal layering of the muscularis propria. It shows that the current case corresponds to a situation never previously reported.

| 1. | Dudley HA, Sinclair IS, Mclaren IF, Mcnair TJ, Newsam JE. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1958;3:206-217. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rudolph CD, Hyman PE, Altschuler SM, Christensen J, Colletti RB, Cucchiara S, Di Lorenzo C, Flores AF, Hillemeier AC, McCallum RW. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in children: report of consensus workshop. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:102-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cucchiara S, Borrelli O, Salvia G, Iula VD, Fecarotta S, Gaudiello G, Boccia G, Annese V. A normal gastrointestinal motility excludes chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction in children. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heneyke S, Smith VV, Spitz L, Milla PJ. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: treatment and long term follow up of 44 patients. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Georgescu EF, Vasile I, Ionescu R. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction: an uncommon condition with heterogeneous etiology and unpredictable outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:954-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kocoshis SA, Reyes J, Todo S, Starzl TE. Small intestinal transplantation for irreversible intestinal failure in children. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1997-2008. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Antonucci A, Fronzoni L, Cogliandro L, Cogliandro RF, Caputo C, De Giorgio R, Pallotti F, Barbara G, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2953-2961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Connor FL, Di Lorenzo C. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: assessment and management. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S29-S36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Smith VV, Milla PJ. Histological phenotypes of enteric smooth muscle disease causing functional intestinal obstruction in childhood. Histopathology. 1997;31:112-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Moore SW, Schneider JW, Kaschula RD. Non-familial visceral myopathy: clinical and pathologic features of degenerative leiomyopathy. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Smith VV, Gregson N, Foggensteiner L, Neale G, Milla PJ. Acquired intestinal aganglionosis and circulating autoantibodies without neoplasia or other neural involvement. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1366-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | De Giorgio R, Guerrini S, Barbara G, Stanghellini V, De Ponti F, Corinaldesi R, Moses PL, Sharkey KA, Mawe GM. Inflammatory neuropathies of the enteric nervous system. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1872-1883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fogel SP, DeTar MW, Shimada H, Chandrasoma PT. Sporadic visceral myopathy with inclusion bodies. A light-microscopic and ultrastructural study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:473-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Knowles CH, Silk DB, Darzi A, Veress B, Feakins R, Raimundo AH, Crompton T, Browning EC, Lindberg G, Martin JE. Deranged smooth muscle alpha-actin as a biomarker of intestinal pseudo-obstruction: a controlled multinational case series. Gut. 2004;53:1583-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | De Giorgio R, Sarnelli G, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. Advances in our understanding of the pathology of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Gut. 2004;53:1549-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McClelland HA, Lewis MJ, Naish JM. Idiopathic steatorrhoea with intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Gut. 1962;3:142-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Naish JM, Capper WM, Brown NJ. Intestinal pseudoobstruction with steatorrhoea. Gut. 1960;1:62-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koh S, Bradley RF, French SW, Farmer DG, Cortina G. Congenital visceral myopathy with a predominantly hypertrophic pattern treated by multivisceral transplantation. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:970-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yamagiwa I, Ohta M, Obata K, Washio M. Intestinal pseudoobstruction in a neonate caused by idiopathic muscular hypertrophy of the entire small intestine. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:866-869. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tanner MS, Smith B, Lloyd JK. Functional intestinal obstruction due to deficiency of argyrophil neurones in the myenteric plexus. Familial syndrome presenting with short small bowel, malrotation, and pyloric hypertrophy. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:837-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mousa H, Hyman PE, Cocjin J, Flores AF, Di Lorenzo C. Long-term outcome of congenital intestinal pseudoobstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2298-2305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kapur RP, Correa H. Architectural malformation of the muscularis propria as a cause for intestinal pseudo-obstruction: two cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12:156-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Di Lorenzo C, Reddy SN, Villanueva-Meyer J, Mena I, Martin S, Hyman PE. Cisapride in children with chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction. An acute, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1564-1570. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Di Lorenzo C, Lucanto C, Flores AF, Idries S, Hyman PE. Effect of sequential erythromycin and octreotide on antroduodenal manometry. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bond GJ, Reyes JD. Intestinal transplantation for total/near-total aganglionosis and intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2004;13:286-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gambarara M, Ferretti F, Diamanti A, Papadatou B, D’Orio F, Sabbi T, Castro M. Parenteral nutrition dependence in pediatric patients: an indication for small bowel transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:882-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ueno T, Wada M, Hoshino K, Sakamoto S, Furukawa H, Fukuzawa M. A national survey of patients with intestinal motility disorders who are potential candidates for intestinal transplantation in Japan. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2029-2031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Uko V, Radhakrishnan K, Alkhouri N. Short bowel syndrome in children: current and potential therapies. Paediatr Drugs. 2012;14:179-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wilhelm SM, Lipari M, Kulik JK, Kale-Pradhan PB. Teduglutide for the Treatment of Short Bowel Syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1209-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Alsolaiman MM, Conzo G, Freund JN S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Ma S