Published online Jun 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6905

Peer-review started: November 18, 2014

First decision: December 11, 2014

Revised: January 10, 2015

Accepted: February 11, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: June 14, 2015

Processing time: 213 Days and 2.9 Hours

AIM: To compare characteristics and prognosis of gastric cancer based on age.

METHODS: A retrospective study was conducted on clinical and molecular data from patients (n = 1658) with confirmed cases of gastric cancer in Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (Seoul, South Korea) from 2003 to 2010 after exclusion of patients diagnosed with lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and metastatic cancer in the stomach. DNA was isolated from tumor and adjacent normal tissue, and a set of five markers was amplified by polymerase chain reaction to assess microsatellite instability (MSI). MSI was categorized as high, low, or stable if ≥ 2, 1, or 0 markers, respectively, had changed. Immunohistochemistry was performed on tissue sections to detect levels of expression of p53, human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)-2, and epidermal growth factor receptor. Statistical analysis of clinical and molecular data was performed to assess prognosis based on the stratification of patients by age (≤ 45 and > 45 years).

RESULTS: Among the 1658 gastric cancer patients, the number of patients with an age ≤ 45 years was 202 (12.2%; 38.9 ± 0.4 years) and the number of patients > 45 years was 1456 (87.8%; 64.1 ± 0.3 years). Analyses revealed that females were predominant in the younger group (P < 0.001). Gastric cancers in the younger patients exhibited more aggressive features and were at a more advanced stage than those in older patients. Precancerous lesions, such as atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, were observed less frequently in the older than in the younger group (P < 0.001). Molecular characteristics, including overexpression of p53 (P < 0.001), overexpression of HER-2 (P = 0.006), and MSI (P = 0.006), were less frequent in gastric cancer of younger patients. Cancer related mortality was higher in younger patients (P = 0.048), but this difference was not significant after adjusting for the stage of cancer.

CONCLUSION: Gastric cancer is distinguishable between younger and older patients based on both clinicopathologic and molecular features, but stage is the most important predictor of prognosis.

Core tip: Whether gastric cancer exhibits distinguishable characteristics based on age remains controversial. In this original article, results are presented that highlight differences in clinical characteristics, pathology, and molecular features of younger and older gastric cancer patients. In particular, the pathologic degree of precancerous lesions associated with each group illuminated potential differences in the pathogenesis of the disease. Although gastric cancer in younger patients presented with more aggressive features, the primary factor in predicting the prognosis of patients with the disease was the stage of the cancer, and not the age of the patient.

- Citation: Seo JY, Jin EH, Jo HJ, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N, Jung HC, Lee DH. Clinicopathologic and molecular features associated with patient age in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(22): 6905-6913

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i22/6905.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6905

Gastric cancer is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer related death worldwide[1,2]. Due to successful screening, the detection of early gastric cancer and the cure rate of gastric cancer have increased annually[1,2]. Regardless of this effort however, mortality of gastric cancer remains high, particularly in East Asian countries.

In general, the peak incidence for gastric cancer is in patients aged 65-74 years[3], with only approximately 3%-10% of gastric cancers overall occurring in patients younger than 40 years[4]. Some case series have focused specifically on younger patients and have reported the cases to be highly advanced gastric cancers (AGC) with poor prognoses[5]. Intriguingly, these gastric cancers were found to be more common in women, frequently diffusely spread in the stomach, more poorly differentiated, and more advanced in stage than gastric cancers from older patients[6,7]. These findings remain controversial[6,8], particularly with regard to patient survival, but have raised the possibility of a disease course that is potentially distinct from that in older patients. Some studies report a better prognosis in younger patients[9,10], while others have found poorer prognoses in young gastric cancer patients relative to older patients[4,11]. Still others have demonstrated no significant differences at all in survival between the two age groups[6-8].

While the majority of reports have focused only on the clinical or pathologic features of gastric cancer in younger patients[4,6-11], molecular characteristics that may distinguish tumors between the two age groups have not been well described. Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether differences in clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics exist in gastric cancer based on age.

This study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH; IRB number: B-1403/244-116), and conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was exempted by the committee.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to identify differences between young (age ≤ 45 years) and older (age > 45 years) patients with gastric cancer. The study was performed on patients who had been diagnosed with gastric cancer in SNUBH from June 2003 to December 2010. Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) patients < 20 years of age; (2) patients diagnosed with gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, or other metastatic cancer located in the stomach; (3) patients for whom a pathologic diagnosis of gastric cancer was not confirmed; (4) patients who did not undergo a stage workup of gastric cancer; (5) patients who were lost in follow-up from SNUBH after diagnosis; or (6) patients who were not initially diagnosed with gastric cancer during the search period.

Demographic factors of patients, characteristics of gastric cancer, pathology, stage, molecular features, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) status, treatment, recurrence, and mortality were reviewed from electronic medical records. Location of the primary tumor was assigned to the proximal, middle, or distal third of the stomach. Gastric cancer that extended into more than two of the three sections was defined as diffusely located[8]. The type of early gastric cancer followed Paris classification (I to III)[12], and the type of AGC followed Borrmann classification (I to IV)[13]. Gastric cancer was staged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system[14].

The pathology of gastric cancers was categorized as intestinal, diffuse, or mixed by Lauren’s classification[15]. The degree of H. pylori infection, neutrophil infiltration, mononuclear cell infiltration, atrophic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia was scored as 0 (absent), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (marked) for statistical analysis, according to the Updated Sydney System[16].

Paraffin-embedded sections (4 μm) were deparaffinized and incubated with monoclonal antibodies against p53, human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)-2, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Detection of primary antibodies and amplification of signal was performed with the streptavidin-biotin method as previously described[17,18]. Staining was recorded as positive or negative expression[17,18]. Overexpression of p53 in > 10% of tumor cells, which generally reflects an underlying mutation in the p53 gene, was as considered positive[19]. Scoring for HER-2 protein expression was performed as previously reported: 0, membrane staining of less than 10% of tumor cells; 1+, faint partial membrane staining in > 10% of tumor cells; 2+, weak to moderate staining of whole membranes in > 10% of tumor cells; and 3+, strong staining of whole membranes in > 10% of tumor cells. Scores of 2+ and 3+ were classified as HER-2 overexpression[18]. A similar scoring method was applied to immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for the EGFR protein, with scores of 2+ and 3+ classified as overexpression[18].

Tumor and normal DNAs were extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue. Five markers (BAT-25, BAT-26, D2S123, D5S346, and D17S250) were used following the guidelines of the International Workshop of the National Cancer Institute. Marker sequences from tumor and matched normal DNAs were amplified with polymerase chain reaction and compared. Tumors with two or more novel markers were classified as microsatellite instability (MSI)-high, whereas tumors with one marker shift were classified as MSI-low. Microsatellite stability was defined as when all markers were identical in tumor and normal DNAs[20].

The primary and secondary outcomes that were compared in this study were mortality and recurrence. Cause of death was categorized as one of the following three scenarios: (1) gastric cancer-related death or mortality due to the progression of gastric cancer; (2) treatment-related death, including severe complications due to surgery or infection after chemotherapy; or (3) other causes not directly related to gastric cancer. Time to recurrence was estimated for those who were cured after endoscopic or surgical resection of gastric cancer.

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD for continuous variables and as frequencies (percent) for categorical variables. A Fisher’s exact test, χ2 analysis, and a Student’s t-test were used for analyzing characteristics of gastric cancer. Independent risk factors for mortality were analyzed with univariate and multivariate analyses using the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analyses. Overall survival and recurrence-free survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. A P≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

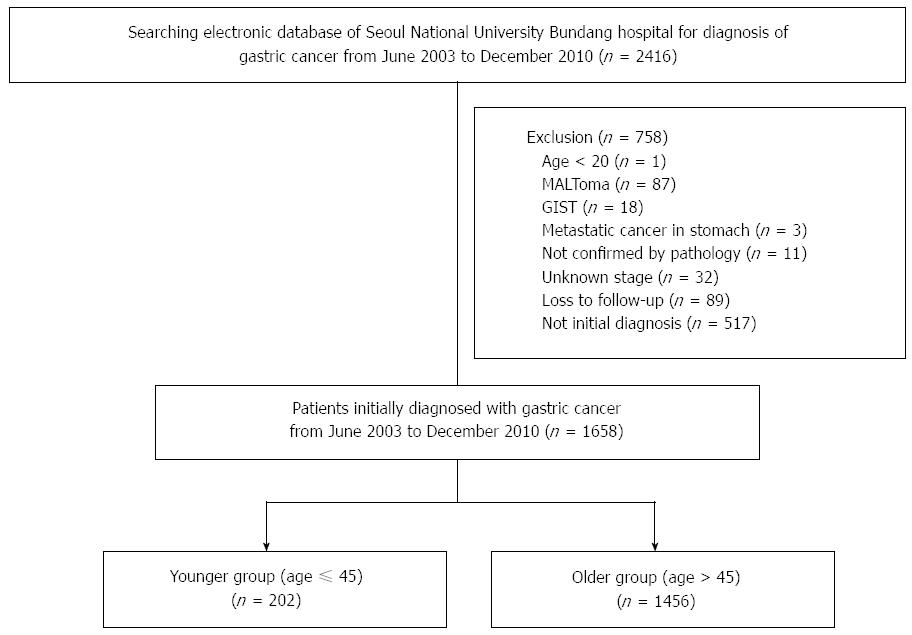

Patients (n = 2416) with a diagnosis of gastric cancer were identified from electronic records from June 2003 to December 2010 at SNUBH. The following patients (n = 758) were excluded from further analysis: < 20 years of age (n = 1); diagnosis of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (n = 87), gastrointestinal stromal tumor (n = 18), metastatic cancer in the stomach (n = 3), pathologic diagnosis of gastric cancer was not confirmed (n = 11), did not undergo a staging workup (n = 32), lost in follow-up (n = 89), and diagnosed with gastric cancer and receiving treatment (n = 517) (Figure 1). The remaining patients (n = 1658) were analyzed.

The number of younger patients (≤ 45 years) was 202 (12.2%), and the number of older patients (> 45 years) was 1456 (87.8%). The mean age of diagnosis was 61.0 ± 0.3 years for all patients, 38.9 ± 0.4 years for younger patients, and 64.1 ± 0.3 years for older patients. A summary of the baseline characteristics for all patients is presented in Table 1. Analyses revealed that the number of female patients was predominant in the younger group (P < 0.001). The majority of younger patients requested medical examination because of symptoms (56.9%). In contrast, gastric cancer was detected in about half of the older patients as a result of screening (49.7%). Older patients had more comorbid diseases (P < 0.001). Gastric cancer in younger patients was more frequently diffusely spread in the stomach (P < 0.001) with more incidences of Borrmann type IV AGC (P < 0.001). There were no differences in the size of the tumor, or expression of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) or carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) based on age.

| Characteristic | Age ≤45 yr (n = 202) | Age > 45 yr (n = 1456) | P value |

| Gender | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 111 (55.0) | 1023 (70.3) | |

| Female | 91 (45.0) | 433 (29.7) | |

| Reason for medical checkup | < 0.001 | ||

| Screening | 70 (34.7) | 724 (49.7) | |

| Symptoms1 | 115 (56.9) | 613 (42.1) | |

| Bleeding/anemia | 13 (6.4) | 105 (7.2) | |

| Weight loss | 4 (2.0) | 14 (1.0) | |

| Comorbidity | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 188 (93.1) | 1200 (82.4) | |

| Yes | 14 (6.9) | 256 (17.6) | |

| Size, cm | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 0.083 |

| CEA | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 0.631 |

| CA 19-9 | 38.3 ± 13.0 | 30.7 ± 6.5 | 0.090 |

| Synchronous gastric cancer | 0.226 | ||

| No | 193 (95.5) | 1414 (97.1) | |

| Yes | 9 (4.5) | 42 (2.9) | |

| Location | < 0.001 | ||

| Proximal | 20 (9.9) | 132 (9.1) | |

| Middle | 88 (43.6) | 433 (29.7) | |

| Distal | 59 (29.2) | 753 (51.7) | |

| Diffuse | 35 (17.3) | 138 (9.5) | |

| EGC type | 116 (57.4) | 889 (61.1) | 0.084 |

| I | 1 (0.5) | 50 (3.4) | |

| II | 113 (55.9) | 820 (56.3) | |

| III | 2 (1.0) | 19 (1.3) | |

| AGC type (Borrmann) | 86 (42.6) | 567 (38.9) | < 0.001 |

| I | 0 (0) | 22 (1.5) | |

| II | 6 (3.0) | 118 (8.1) | |

| III | 47 (23.3) | 334 (22.9) | |

| IV | 31 (15.3) | 71 (4.9) | |

The pathology and the stages of gastric cancer for all patients are presented in Table 2. Statistical analyses revealed that more tumors in younger patients were diagnosed as diffuse based on Lauren’s classification (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Depth of invasion, frequency of distant metastasis, and final stage were all higher in the younger patient group (P = 0.001). The pathologic features of venous (P = 0.024) and perineural invasion (P = 0.043) were also more frequently observed in gastric cancers from younger patients. In contrast, baseline adenoma occurred less often in these patients (P < 0.001).

| Variable | Age ≤45 yr(n = 202) | Age > 45 yr (n = 1456) | P value |

| Pathology (Lauren) | < 0.001 | ||

| Intestinal | 39 (19.3) | 870 (59.8) | |

| Diffuse | 157 (77.7) | 526 (36.1) | |

| Mixed | 6 (3.0) | 60 (4.1) | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 117 (57.9) | 876 (60.2) | |

| T2 | 10 (5.0) | 143 (9.8) | |

| T3 | 15 (7.4) | 186 (12.8) | |

| T4 | 33 (16.3) | 146 (10.0) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.052 | ||

| N0 | 122 (60.4) | 962 (66.1) | |

| N1 | 8 (4.0) | 127 (8.7) | |

| N2 | 15 (7.4) | 74 (5.1) | |

| N3 | 25 (12.4) | 155 (10.6) | |

| Distant metastasis | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | 153 (75.7) | 1267 (87.0) | |

| M1 | 49 (24.3) | 189 (13.0) | |

| Stage | < 0.001 | ||

| I | 122 (60.4) | 954 (65.5) | |

| II | 10 (5.0) | 149 (10.2) | |

| III | 21 (10.4) | 166 (11.4) | |

| IV | 49 (24.3) | 187 (12.8) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.612 | ||

| No | 121 (59.9) | 902 (62.0) | |

| Yes | 50 (24.8) | 408 (28.0) | |

| Venous invasion | 0.024 | ||

| No | 149 (73.8) | 1207 (82.9) | |

| Yes | 22 (10.9) | 102 (7.0) | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.043 | ||

| No | 125 (61.9) | 1042 (71.6) | |

| Yes | 46 (22.8) | 264 (18.1) | |

| Baseline adenoma | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 165 (81.7) | 1101 (75.6) | |

| Yes | 4 (2.0) | 195 (13.4) |

Treatment for gastric cancer varied among patients of the study. For example, not all patients underwent curative resection. The various treatment strategies utilized are presented in Table 3. A significantly higher percentage of younger patients received palliative resection for AGC (P = 0.018), N3 dissection (P = 0.017), and chemotherapy (P < 0.001) compared to older patients.

| Variable | Age ≤45 yr(n = 202) | Age > 45 yr (n = 1456) | P value |

| Endoscopic resection | 9 (4.5) | 192 (13.2) | 0.516 |

| EMR | 6 (3.0) | 104 (7.1) | |

| ESD | 3 (1.5) | 88 (6.0) | |

| Operation | 172 (85.1) | 1160 (79.7) | 0.018 |

| Curative resection | 157 (77.7) | 1108 (76.1) | |

| Palliative resection | 15 (7.4) | 52 (3.6) | |

| LN dissection | 0.017 | ||

| Not performed | 9 (4.5) | 24 (1.6) | |

| N1 | 62 (30.7) | 404 (27.7) | |

| N2 | 95 (47.0) | 714 (49.0) | |

| N3 | 6 (3.0) | 18 (1.2) | |

| Radiation | 0.101 | ||

| No | 197 (97.5) | 1440 (98.9) | |

| Yes | 5 (2.5) | 16 (1.1) | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 132 (65.3) | 1194 (82.1) | |

| Yes | 70 (34.7) | 261 (17.9) |

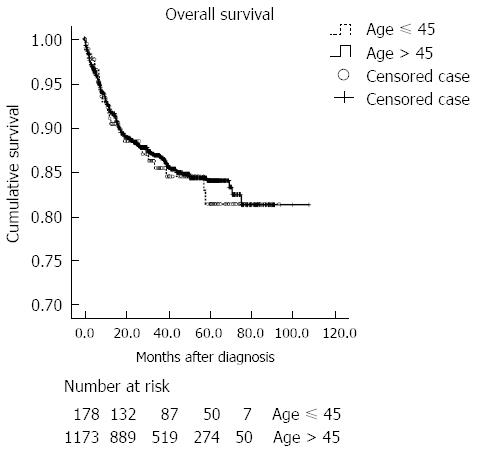

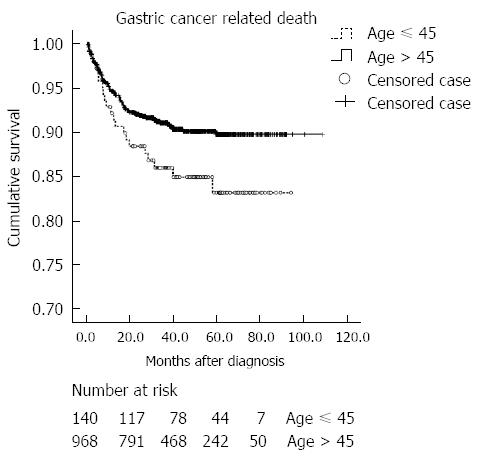

The clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 4. The mean time for follow-up was 35.4 ± 23.7 mo. The mean time to recurrence was 17.8 ± 4.1 in younger patients, and 16.9 ± 1.3 mo in older patients. The recurrence rate for cured patients was similar in both age groups, with peritoneal metastasis as the most common site of recurrence. Furthermore, gastric cancer-related death was the most common cause of death in both groups. Mortality occurred in 26 (12.9%) and 159 (10.9%) of younger and older patients, respectively. Cumulative probabilities of overall mortality were not different between the two age groups (Figure 2). The cumulative rate of gastric cancer-related death was significantly higher in the younger age group (P = 0.048) (Figure 3). However, when adjusted for the stage, gastric cancer-related death was not significantly different between the two age groups (P = 0.191). The cumulative rate of treatment-related death was not different between the two age groups.

| Variable | Age ≤45 yr(n = 202) | Age > 45 yr(n = 1456) |

| Mean follow-up duration, mo | 36.9 ± 25.5 | 35.2 ± 23.5 |

| Mean time to recurrence, mo1 | 17.8 ± 4.1 | 16.9 ± 1.3 |

| Cured patients | 162 (80.2) | 1246 (85.6) |

| Recurrence | 17 (10.5) | 127 (10.2) |

| Mortality | ||

| Survival | 116 (57.4) | 838 (57.6) |

| Death | 26 (12.9) | 159 (10.9) |

| Loss to follow-up | 60 (29.7) | 459 (31.5) |

| Cause of death | ||

| Gastric cancer-related death | 21 (10.4) | 87 (6.0) |

| Treatment-related death | 2 (1.0) | 13 (0.9) |

| Other causes2 | 0 (0) | 21 (1.4) |

| Not available | 3 (1.5) | 38 (2.6) |

The results of molecular pathology are shown in Table 5. Gastric cancer in the younger age group had significantly less positive staining for p53 (P < 0.001), HER-2 overexpression (P = 0.006), and MSI (P = 0.006). EGFR protein expression, however, did not differ between the two groups (P = 0.899).

| Variable | Age ≤45 yr(n = 202) | Age > 45 yr(n = 1456) | P value |

| p53 | < 0.001 | ||

| Negative | 123 (60.9) | 681 (46.8) | |

| Positive | 44 (21.8) | 560 (38.5) | |

| MSI | 0.006 | ||

| Stable | 85 (42.1) | 566 (38.9) | |

| MSI-L | 4 (2.0) | 43 (3.0) | |

| MSI-H | 1 (0.5) | 79 (5.4) | |

| HER-2 status | 0.006 | ||

| Negative | 78 (38.6) | 528 (36.3) | |

| Positive | 6 (3.0) | 125 (8.6) | |

| EGFR status | 0.899 | ||

| Negative | 94 (46.5) | 674 (46.3) | |

| Positive | 12 (5.9) | 99 (6.8) |

The status of H. pylori and related changes of the stomach are presented in Table 6. The level of H. pylori in pathologic specimens was higher in younger patients (P = 0.012). The pathologic degrees of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were, however, significantly higher in older patients (P < 0.001).

| Variable | Age ≤45 yr(n = 202) | Age > 45 yr(n = 1456) | P value |

| Helicobacter pylori grade | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.012 |

| Neutrophil infiltration | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.866 |

| Mononuclear cell infiltration | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.679 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

Risk factors for overall mortality in gastric cancer patients were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model (Table 7). In univariate analyses, the following were significant risk factors for mortality: non-curative resection, elevated CEA, elevated CA 19-9, larger size of gastric cancer, diffuse pathology, higher T, N, or M stage, final stage, and lymphatic, venous, and perineural invasion (all P < 0.001). Multivariate analyses demonstrated that only M stage (adjusted HR = 6.70; 95%CI: 1.58-24.49; P = 0.010) and final stage (adjusted HR = 10.78; 95%CI: 2.69-43.22; P = 0.001) were independent risk factors for mortality.

| Parameter | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age ( ≤ 45/> 45 yr) | 1.10 (0.72-1.66) | 0.664 | ||

| Gender (male/female) | 0.87 (0.63-1.19) | 0.384 | ||

| Curative resection (no/yes) | 6.38 (4.33-9.40) | < 0.001 | ||

| CEA | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | < 0.001 | ||

| CA19-9 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | < 0.001 | ||

| Size, cm | 1.24 (1.20-1.28) | < 0.001 | ||

| Pathology | ||||

| Intestinal | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Diffuse | 2.77 (2.03-3.78) | < 0.001 | ||

| Mixed | 1.95 (0.89-4.26) | 0.095 | ||

| T stage (III, IV vs I, II) | 26.07 (16.42-41.40) | < 0.001 | ||

| N stage (N+ vs N-) | 21.29 (12.81-35.36) | < 0.001 | ||

| M stage (M+ vs M-) | 42.17 (30.75-57.84) | < 0.001 | 6.70 (1.58-24.49) | 0.010 |

| Stage (III, IV vs I, II) | 46.39 (30.75-69.98) | < 0.001 | 10.78 (2.69-43.22) | 0.001 |

| Lymphatic invasion (yes/no) | 11.84 (7.45-18.83) | < 0.001 | ||

| Venous invasion (yes/no) | 14.75 (9.95-21.87) | < 0.001 | ||

| Perineural invasion (yes/no) | 14.34 (9.42-251.85) | < 0.001 | ||

| Atrophic gastritis | 1.06 (0.77-1.45) | 0.736 | ||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 1.00 (0.76-1.30) | 0.977 | ||

| p53 (positive/negative) | 1.45 (0.99-2.12) | 0.058 | ||

| MSI (MSI-L vs stable) | 1.30 (0.53-3.21) | 0.565 | ||

| MSI (MSI-H vs stable) | 0.82 (0.53-1.76) | 0.602 | ||

| HER-2 (positive/negative) | 0.57 (0.26-1.25) | 0.158 | ||

| EGFR (positive/negative) | 0.66 (0.27-1.65) | 0.377 | ||

This retrospective study of 1658 gastric cancer patients indicates that clinicopathologic features, such as being female, Borrmann type IV AGC, and diffuse type pathology, were more commonly associated with the younger group of patients. Gastric cancers from patients ≤ 45 years of age exhibited more advanced stages than from patients > 45 years, but younger patients received more aggressive treatment such as palliative resection and chemotherapy. These findings are in agreement with previous studies[6-8,11].

One of the most intriguing implications of the results is that the pathogenesis of gastric cancer may differ between age groups. H. pylori infection is most commonly acquired in children[21], and with increasing age, the stomach changes stepwise from atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, p53 alteration, and dysplasia, to intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma; this transition is known as Correa’s cascade[22]. Therefore, the presence of higher degrees of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, and increased incidence of p53 overexpression, adenoma, and intestinal-type gastric cancer observed in older patients of this cohort largely corroborates this model. Higher grade H. pylori infection in the absence of precancerous changes in younger patients from the cohort, however, does not support this model. In the majority of cases from this cohort, the grade of H. pylori infection was evaluated from resected cancer specimens, which were primarily located in the distal third of the stomach of older patients (51.7%). As atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were more common in older patients, the degree of H. pylori infection as determined from pathologic specimens could be underestimated[23]. In fact, positivity of H. pylori determined from serology, pathology, and the rapid urease test did not differ between age groups (64.7% vs 62.4% in younger and older patients, respectively). The results of the current study indicate that gastric cancer in older patients tends to progress through a series of sequential changes starting with H. pylori infection and leading to intestinal-type gastric cancer. In younger patients, however, a gastric cancer of a diffuse pathology was more prevalent. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to reveal potential age-associated biologic differences in gastric cancer and its development.

The results also highlight important differences in the molecular pathology of gastric cancer from the two groups. First, a higher incidence of MSI was detected in tumors from older patients. These results agree with a previous report that demonstrated an increased frequency of MSI specifically in gastric cancers with an antral location, intestinal pathology, and lower incidence of lymph node metastasis[17]. Second, while overexpression of HER-2 has been reported to predict poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients[24,25], an association between HER-2 and age has not yet been identified. The results of the current study indicate that overexpression of HER-2 in gastric cancer is in fact more common in older patients.

Interestingly, while younger patients exhibited a more advanced stage of gastric cancer, the overall mortality rate did not differ between the two age groups in this cohort. Younger patients did have a higher cumulative rate of cancer-related death compared to the older age group. However, this difference between the two age groups was not statistically significant once the data was adjusted for the stage of gastric cancer. Thus, these findings suggest that survival is not associated with age, which is in agreement with previous studies[6-8]. At the same time, treatment differences do exist between the two groups. For example, in spite of the higher stage of gastric cancer, younger patients received more palliative resections than older patients. Because it is possible that palliative gastrectomy could improve overall survival[26,27], aggressive treatment in younger patients might have extended their overall survival. However, despite potential advantage in treatment strategies in younger patients, gastric cancer-related death did not differ between the two groups when adjusted by stage. Further support for this conclusion is gained from the results that only stage and distant metastasis could predict mortality, whereas age was not found to be an independent risk factor in a Cox proportional hazards model. Therefore, other factors, such as the diffuse pathology or size, might more strongly influence overall survival.

Several limitations are inherent in this study, primarily because of the retrospective design. First, molecular pathology was not performed on all tumors. Results for MSI are particularly inconsistent, as the method described here has been applied to tumor samples starting only in the year 2007. Second, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is required to validate IHC scores of 2+ for the accurate diagnosis of the overexpression of HER-2[28]. As FISH was not performed on tumor sections from most patients, overexpression of HER-2 was determined based on IHC results alone. Third, the influence of chemotherapeutic treatment or specific protocol was not evaluated. A greater proportion of younger patients received chemotherapy than older patients, and furthermore, different regimens could affect survival.

Nevertheless, our study presents several novel findings. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to identify differences based on age in the molecular pathology and H. pylori-associated precancerous changes of gastric cancer. Therefore, a novel concept on the basis of these results is that the disease pathogenesis differs between the two groups. However, additional studies are necessary to validate the role of H. pylori in disease progression, as well as the accompanying molecular changes in gastric cancer, of younger patients.

In conclusion, gastric cancer in younger and older patients differed in clinical characteristics, pathology, and molecular pathology. Although gastric cancer in younger patients often presented with more aggressive features, the primary factor in predicting prognosis was the stage of the gastric cancer and not the age of the patient.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Endoscopy Center of the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (Seoul, South Korea).

Clinicopathologic features differ between young and old patients with gastric cancer. Young patients predominantly are female, and their cancers display a more poorly differentiated pathology and advanced stage compared to older patients.

Molecular differences and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-associated changes, such as atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, have not yet been elucidated based on age. Whether prognosis is related to age also remains controversial. Therefore, this study aimed to illuminate differences in clinicopathologic, molecular, and biologic characteristics of gastric cancer associated with age.

Although gastric cancers in younger patients displayed more aggressive features than in older patients, cancer-related mortality did not differ between the two age groups after adjustment for the stage of cancer. Gastric cancer in younger patients was less frequently associated with atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, overexpression of p53, and microsatellite instability than in older patients.

The significant differences in the pathologic degree of precancerous lesions and in molecular pathology indicated a distinct pathogenesis of the disease associated with age. The results are consistent with the model that gastric cancer in older patients tends to follow a dynamic series of sequential changes initiated by H. pylori infection and leading to intestinal-type gastric cancer. As diffuse-type gastric cancer predominated in younger patients, molecular changes due to factors other than H. pylori infection may be more important in pathogenesis in patients ≤ 45 years of age. Based on these results, prevention or tailored therapy based on age could be considered in the future.

Gastric cancer patients were stratified as younger or older according to the age of 45 years.

This is a very interesting article that discusses a little population studied in gastric cancer where was observed an increase in the disease especially in the West. A population of a considerable volume center was analyzed, complementing clinical aspects with molecular variables and even preneoplastic lesions.

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9215] [Cited by in RCA: 9876] [Article Influence: 759.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1754] [Cited by in RCA: 1914] [Article Influence: 119.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Wu CW, Tsay SH, Hsieh MC, Lo SS, Lui WY, P’eng FK. Clinicopathological significance of intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in Taiwan Chinese. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:1083-1088. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Theuer CP, de Virgilio C, Keese G, French S, Arnell T, Tolmos J, Klein S, Powers W, Oh T, Stabile BE. Gastric adenocarcinoma in patients 40 years of age or younger. Am J Surg. 1996;172:473-46; discussion 473-46;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kath R, Fiehler J, Schneider CP, Höffken K. Gastric cancer in very young adults: apropos four patients and a review of the literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:233-237. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Park JC, Lee YC, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee SK, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB. Clinicopathological aspects and prognostic value with respect to age: an analysis of 3,362 consecutive gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hsieh FJ, Wang YC, Hsu JT, Liu KH, Yeh CN. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of gastric cancer patients aged 40 years or younger. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:304-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kulig J, Popiela T, Kolodziejczyk P, Sierzega M, Jedrys J, Szczepanik AM. Clinicopathological profile and long-term outcome in young adults with gastric cancer: multicenter evaluation of 214 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moreira H, Pinto-de-Sousa J, Carneiro F, Cardoso de Oliveira M, Pimenta A. Early onset gastric cancer no longer presents as an advanced disease with ominous prognosis. Dig Surg. 2009;26:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eguchi T, Takahashi Y, Yamagata M, Kasahara M, Fujii M. Gastric cancer in young patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:22-26. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Smith BR, Stabile BE. Extreme aggressiveness and lethality of gastric adenocarcinoma in the very young. Arch Surg. 2009;144:506-510. [PubMed] |

| 12. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kajitani T. The general rules for the gastric cancer study in surgery and pathology. Part I. Clinical classification. Jpn J Surg. 1981;11:127-139. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 820] [Article Influence: 54.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Stolte M, Meining A. The updated Sydney system: classification and grading of gastritis as the basis of diagnosis and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:591-598. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Wu MS, Lee CW, Shun CT, Wang HP, Lee WJ, Chang MC, Sheu JC, Lin JT. Distinct clinicopathologic and genetic profiles in sporadic gastric cancer with different mutator phenotypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:403-411. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Choi JS, Kim MA, Lee HE, Lee HS, Kim WH. Mucinous gastric carcinomas: clinicopathologic and molecular analyses. Cancer. 2009;115:3581-3590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Seo YH, Joo YE, Choi SK, Rew JS, Park CS, Kim SJ. Prognostic significance of p21 and p53 expression in gastric cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 2003;18:98-103. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kim JY, Shin NR, Kim A, Lee HJ, Park WY, Kim JY, Lee CH, Huh GY, Park do Y. Microsatellite instability status in gastric cancer: a reappraisal of its clinical significance and relationship with mucin phenotypes. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pounder RE, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 2:33-39. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum S, Archer M. A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet. 1975;2:58-60. [PubMed] |

| 23. | El-Zimaity HMT O, Kim JG, Akamatsu T, Gürer IE, Simjee AE, Graham DY. Geographic differences in the distribution of intestinal metaplasia in duodenal ulcer patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:666-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen C, Yang JM, Hu TT, Xu TJ, Yan G, Hu SL, Wei W, Xu WP. Prognostic role of human epidermal growth factor receptor in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2013;44:380-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Terashima M, Kitada K, Ochiai A, Ichikawa W, Kurahashi I, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, Sano T, Imamura H, Sasako M. Impact of expression of human epidermal growth factor receptors EGFR and ERBB2 on survival in stage II/III gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5992-6000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lasithiotakis K, Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Kaklamanos I, Zoras O. Gastrectomy for stage IV gastric cancer. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:2079-2085. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Sun J, Song Y, Wang Z, Chen X, Gao P, Xu Y, Zhou B, Xu H. Clinical significance of palliative gastrectomy on the survival of patients with incurable advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hofmann M, Stoss O, Shi D, Büttner R, van de Vijver M, Kim W, Ochiai A, Rüschoff J, Henkel T. Assessment of a HER2 scoring system for gastric cancer: results from a validation study. Histopathology. 2008;52:797-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 868] [Article Influence: 48.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: de Tejada AH, Garrido M, Sendur MAN S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH