Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5995

Peer-review started: November 18, 2014

First decision: December 26, 2014

Revised: January 15, 2015

Accepted: February 11, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 183 Days and 7.9 Hours

AIM: To assess the efficacy and safety of a patient-positioning device (EZ-FIX) for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

METHODS: A total of 105 patients were randomized to the EZ-FIX (n = 53) or non-EZ-FIX (n = 52) group in this prospective study. Midazolam and propofol, titrated to provide an adequate level of sedation during therapeutic ERCP, were administered by trained registered nurses under endoscopist supervision. Primary outcome measures were the total dose of propofol and sedative-related complications, including hypoxia and hypotension. Secondary outcome measures were recovery time and sedation satisfaction of the endoscopist, nurses, and patients.

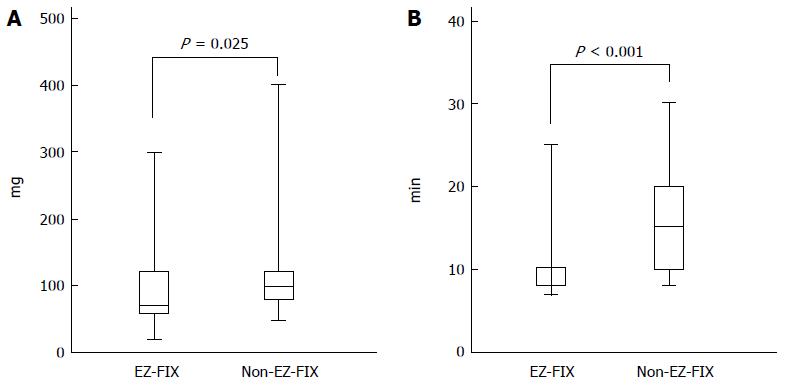

RESULTS: There was no significant difference in the rate of hypoxia, but there was a statistical trend (EX-FIX group; n = 4, 7.55%, control group; n = 6, 11.53%, P = 0.06). The mean total dose of propofol was lower in the EZ-FIX group than in the non-EZ-FIX group (89.43 ± 49.8 mg vs 112.4 ± 53.8 mg, P = 0.025). In addition, the EZ-FIX group had a shorter mean recovery time (11.23 ± 4.61 mg vs 14.96 ± 5.12 mg, P < 0.001). Sedation satisfaction of the endoscopist and nurses was higher in the EX-FIX group than in the non-EZ-FIX group. Technical success rates of the procedure were 96.23% and 96.15%, respectively (P = 0.856). Procedure-related complications did not differ by group (11.32% vs 13.46%, respectively, P = 0.735).

CONCLUSION: Using EZ-FIX reduced the total dose of propofol and the recovery time, and increased the satisfaction of the endoscopist and nurses.

Core tip: Although the incidence of sedation-related complications is low, it is closely associated with endoscopy-related morbidity and mortality. Many studies on the efficacy and safety of various sedative drugs have been conducted, but none used a patient-positioning device. We planned this study to improve the safety and efficacy of sedation during endoscopy by using a patient-positioning device (EZ-FIX).

- Citation: Lee S, Han JH, Lee HS, Kim KB, Lee IK, Cha EJ, Shin YD, Park N, Park SM. Efficacy and safety of a patient-positioning device (EZ-FIX) for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 5995-6000

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/5995.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5995

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an advanced upper endoscopic procedure, and is useful for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatobiliary disorders[1]. However, ERCP is an invasive procedure of considerable duration and causes substantial discomfort to patients. Thus, a deeper level of sedation may be necessary to ensure the success and safety of the procedure. Deep sedation during ERCP with careful monitoring minimizes patient movement, allowing the endoscope to be manipulated precisely with little interruption. Although the incidence of sedation-related complications is low, it is closely associated with endoscopy related morbidity and mortality. EZ-FIX is a patient-positioning device that uses polyethylene particles and compressed air that is expected to contribute to sedation safety by fixing the position of the patient. Such fixation avoids the transient failure of maintenance of sedation that can occur during ERCP procedures. Studies on the efficacy and safety of various sedative drugs have been published, but none of these studies used a patient-positioning device. This study was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of the EZ-FIX during ERCP.

This prospective, randomized trial included 105 patients who underwent therapeutic ERCP between April 2013 and March 2014, at the Chungbuk National University Hospital. The sample-size calculation was based on a preliminary study. Consecutive patients who provided informed consent and were to undergo ERCP were assigned randomly to the EZ-FIX group (n = 53) or the non-EZ-FIX group (n = 52). Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years of age, had an ASA classification of “V”, had a history of complications during sedative endoscopy, adverse reactions to propofol or midazolam injection, severe obstructive sleep apnea, pregnancy, or an allergy to eggs or soybeans.

Therapeutic ERCP was performed by one experienced endoscopist who had performed over 1000 therapeutic ERCP procedures during the previous 5 years (Han JH). Trained registered nurses, with experience of over 100 therapeutic ERCP procedures, administered all medications, monitored patients, and prepared medical records under the supervision of the physician performing the ERCP. They were assisted during ERCP by one gastroenterology fellow and two other nurses.

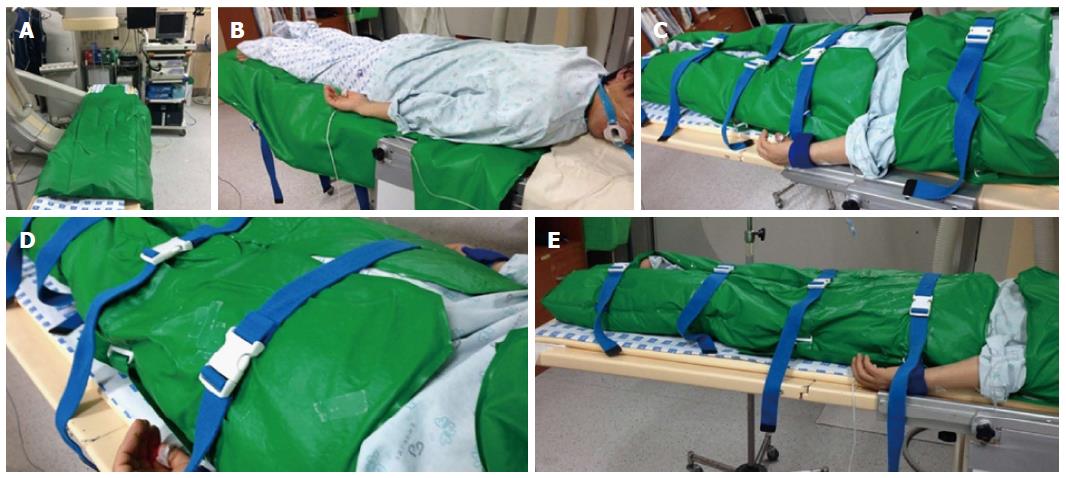

A patient-positioning device (EZ-FIX, Arlico Medical, South Korea) was used in this study. EZ-FIX is filled with tiny polystyrene particles and compressed air and is covered with polyurethane. First, the EZ-FIX is inflated after setting the device on the procedure table in a loose shape. The patient is then placed on the EZ-FIX in the desired posture. Air is removed from the EZ-FIX by vacuum to “copy” and fix the shape of the patient’s posture (Figure 1). Sedatives were then administered after placement of monitoring devices.

The level of sedation was defined according to the ASA classifications: minimal, moderate, deep sedation, and general anesthesia[2]. Minimal sedation is a state in which the patient can respond normally to verbal stimulation. With moderate sedation, the patient can respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by light tactile stimulation. Under deep sedation, the patient cannot be aroused easily, but responds purposefully following repeated or painful stimulation. In this study, the target level of sedation was deep sedation, which is used for advanced endoscopic procedures, including ERCP and endoscopic submucosal dissection.

The initial intravenous bolus dose of midazolam was 0.05 mg/kg; a half dose was used in those over 70 years old and ASA III-IV patients. A 20-mg propofol bolus was also injected when a patient failed to achieve sedation 3 min after the first injection, and 20-mg doses of propofol were injected repeatedly at 1-min intervals until sedation was achieved. Additional midazolam 0.025 mg/kg was administered when the procedure time was predicted to be excessive or the demand for propofol was too frequent. All the subjects gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Chungbuk National University (CBNUH201304018002) and is registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS, KCT000137).

Primary outcome measures were the total dose of propofol and sedative-related complications, including hypoxia and hypotension. Secondary outcome measures were recovery time and sedation satisfaction of the endoscopist, nurses, and patients. Procedure time was counted from the dosing of sedatives until withdrawal of the endoscope. Recovery time was defined from the completion of the procedure until the Aldrete score reached 10 points. The total doses of midazolam and propofol administered during the procedure were measured. The endoscopists and sedation nurses completed a questionnaire, using a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS), which assessed patient cooperation and overall satisfaction with sedation and the procedure (ranging from 0 = poor, to 10 = excellent). Safety was monitored by measuring systolic and diastolic pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation before and after the procedure and at 10-min intervals during the procedure. Procedure-related complications recorded included bleeding, perforation, and pancreatitis.

Baseline data from the patients in the two groups were compared using a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed continuous variables and a Mann-Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The SPSS software (ver. 13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis.

In total, 105 patients were enrolled in this prospective study and were randomized to the EZ-FIX group (n = 53) or the non-EZ-FIX group (n = 52). The characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, gender, body weight, duration of procedure, or ASA score.

| EZ-FIX(n = 53) | Non-EZ-FIX(n = 52) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 68.0 ± 15.4 | 67.0 ± 14.0 | 0.837 |

| Gender (male: female) | 55:45 | 56:44 | 0.914 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.42 ± 10.36 | 60.79 ± 10.75 | 0.507 |

| Procedure time (min) | 24.66 ± 13.58 | 27.15 ± 11.73 | 0.317 |

| ASA classification | 0.458 | ||

| 1-2 | 42 (79.2) | 38 (73.1) | |

| 3-4 | 11 (20.8) | 14 (26.9) |

Table 2 shows that the total dose of midazolam and the induction time were not significantly different between the groups (2.42 ± 1.88 mg vs 2.41 ± 1.91 mg, P = 0.976, and 3.37 ± 0.94 min vs 3.72 ± 1.02 min, P = 0.067, respectively). The mean total dose of propofol was lower in the EZ-FIX group than in the non-EZ-FIX group (89.43 ± 49.8 mg vs 112.4 ± 53.8 mg, P = 0.025). In addition, the EZ-FIX group had a shorter mean recovery time (11.23 ± 4.61 mg vs 14.96 ± 5.12 mg, P < 0.001; Figure 2). Based on the VAS, patient satisfaction scores did not differ significantly between the groups. However, the satisfaction scores of both the endoscopist and nurses were significantly higher in the EZ-FIX group than in the non-EZ-FIX group (8.11 ± 0.99 vs 6.54 ± 1.40, P < 0.001, and 7.81 ± 1.03 vs 6.02 ± 1.74, P < 0.001, respectively).

| EZ-FIX(n = 53) | Non-EZ-FIX(n = 52) | P value | |

| Total dose of midazolam | 2.42 ± 1.88 | 2.41 ± 1.91 | 0.976 |

| Total dose of propofol | 89.43 ± 49.8 | 112.4 ± 53.8 | 0.025 |

| Induction time, min | 3.37 ± 0.94 | 3.72 ± 1.02 | 0.067 |

| Recovery time, min | 11.23 ± 4.61 | 14.96 ± 5.12 | < 0.001 |

| Pt. satisfaction score | 7.26 ± 2.25 | 7.29 ± 2.47 | 0.722 |

| Dr. satisfaction score | 8.11 ± 0.99 | 6.54 ± 1.40 | < 0.001 |

| Nr. satisfaction score | 7.81 ± 1.03 | 6.02 ± 1.74 | < 0.001 |

Adverse events are shown in Table 3. There were four cases of hypoxemia in the EZ-FIX group and six cases in the non-EZ-FIX group (P = 0.06). Severe hypotension was not observed in either group and no patient required artificial ventilation such as mask bagging and intubation. Procedure-related complications were similar between the two groups (6 vs 7, P = 0.775).

| EZ-FIX(n = 53) | Non-EZ-FIX(n = 52) | P value | |

| Below 90% in SaO2 for ≥ 30 s | 4 (3.8) | 6 (5.7) | 0.060 |

| ↓ 20 mmHg in BP | 8 (7.6) | 9 (8.6) | 0.800 |

| ↓ 20% in PR | 3 (2.9) | 3 (2.9) | 1 |

| Death | - | - | - |

| Procedure-related complications | 0.735 | ||

| Pancreatitis | 5 | 4 | |

| Bleeding | 1 | 2 | |

| Perforation | - | 1 |

Since its introduction in 1968, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) has become a commonly performed endoscopic procedure[1]. The diagnostic and therapeutic utility of ERCP for a variety of disorders, including the management of biliary and pancreatic neoplasms, and the postoperative management of biliary perioperative complications, has been demonstrated[3-5]. However, ERCP is an uncomfortable and high-risk therapeutic procedure that cannot be performed without adequate sedation or general anesthesia. Patients must be administered agents to induce moderate-to-deep sedation to tolerate the ERCP procedure. The use of propofol for endoscopic sedation has increased markedly in recent years, mainly due to its favorable pharmacokinetic profile compared with “traditional” endoscopy sedation drugs, such as benzodiazepines and opioids[6-10]. When administered intravenously, propofol rapidly crosses the blood-brain barrier and activates aminobutyric acid to induce sedation, amnesia, and sleep. Sedative effects occur within, on average, 30-60 s after IV administration, and patients recover rapidly due to the short 1.3-1.4-min half-life[11]. However, propofol has no reversal agent; moreover, negative cardiac inotropy, including decreases in cardiac output, systemic vascular resistance, arterial pressure, and respiratory depression can occur[12,13]. Thus, it is recommended that propofol should be administered only by anesthesia specialists[14]. Although a large volume of data shows the safety of endoscopist-directed propofol[15-23], it is important to be aware of sedation-related complications due to the increase in the number of elderly patients with multiple underlying comorbidities and its nature as an advanced endoscopic technique that demands longer procedure times and deeper sedation. In clinical practice, it is common to combine propofol with additional drugs (benzodiazepine/opioid/ketamine), so-called “balanced propofol sedation” (BPS), which allows the propofol dose to be reduced and seems to be associated with less-frequent need for assisted ventilation, although this has not been demonstrated in head-to-head comparisons[23-27]. In an effort to reduce the incidence of sedation-related complications, we performed this study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a patient-positioning device.

Respiratory depression is more frequent in ERCP because the procedure is performed in the prone position. Several devices can be used, such as cushions to maintain the airway by lifting the right shoulder, but these are not commercial products. Recently, a transformable patient-positioning device (EZ-FIX, Arlico Medical, South Korea) was designed to make the procedure more efficient. EZ-FIX contains polystyrene balls in a soft and non-slip polyurethane cover, which provides flexibility in the changing postures of patients. Inflation with air and deflation with a vacuum facilitate rapid changes in and fixation of the posture of the patient. Patients are more comfortable in the desired position and maintain a stable posture during the procedure. In addition, EZ-FIX exerts a body-temperature-protecting effect and assists in turning the patient over.

Our study demonstrated that using EZ-FIX reduced both the total dose of propofol and the recovery time. The advantages of propofol sedation are the rapid onset and short recovery time. However, it is difficult to predict the timing when patients who have long procedure times are released from sedation, and this sometimes leads to a dangerous situation. Therefore, propofol is frequently administered before a return to minimal sedation, which can lead to over-sedation. However, these intermittent propofol injections in advance are not necessary with EZ-FIX, due to the immobilization of patients. Thus, the propofol dose can be reduced and the recovery time shortened. The higher satisfaction of the endoscopist and nurses in the EZ-FIX group was thought to be due to inhibition of unpredictable movements of the patient. A significant reduction in the amount of propofol required for deep sedation could theoretically decrease the risk of sedation-related complications. However, in this study, the rate of neither hypotension nor hypoxemia differed significantly between the groups. EZ-FIX may lead to a lower incidence of sedative-related complications in a larger-scale study. The rate of procedure-related complications did not differ between the groups, possibly due more to the type of procedure performed and underlying diseases than sedation methods.

This study had several limitations in that the sample size was small, and patients with ASA V, severe sleep apnea, and pulmonary disease were excluded. A double-blind design was not possible in that the endoscopist and nurses could see the device, which might have caused bias in the satisfaction scores. Further studies in patients with various characteristics are needed to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of EZ-FIX.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that use of the EZ-FIX provided increased satisfaction for the endoscopist and nurses, reduced the total dose of propofol, and decreased recovery time. Thus, we suggest that the EZ-FIX may be valuable in advanced endoscopic procedures, including ERCP.

The authors would like to thank the nursing staff (Mi Suk Kim, Hee Kyung Ryu, and Hae Sook Han) at the participating center for their support and assistance in this study.

Advanced endoscopic procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are long, and patients require deep consistent sedation. The use of propofol for endoscopic sedation has increased due to its useful pharmacokinetic profile. However, no reversal agent is available and cardiovascular and respiratory complications can result.

Propofol has been combined with other drugs to decrease sedation-related complications; this also allows the propofol dose to be reduced. However, studies on relevant patient-positioning devices have not yet appeared.

This is the first study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a patient-positioning device (EZ-FIX) for ERCP. EZ-FIX increased the satisfaction levels of both the endoscopist and nurses, reduced the total dose of propofol required, and decreased recovery time. It is important to consider sedative drugs and external devices in combination to improve the efficacy and safety of sedation.

This study suggests that the EZ-FIX patient-positioning device could be valuable in advanced endoscopic procedures, such as ERCP, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and peroral endoscopic myotomy.

EZ-FIX is a patient-positioning device (Arlico Medical, South Korea) that is filled with tiny polystyrene particles and compressed air and is covered with polyurethane.

This study affords useful information and suggests that a patient-positioning device could be valuable during ERCP. The authors show that this device (EZ-FIX) could reduced the total dose of propofol required, and decreased recovery time. EZ-FIX might be a valuable aid during advanced endoscopic procedures.

| 1. | McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968;167:752-756. [PubMed] |

| 2. | American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Baron TH, Mallery JS, Hirota WK, Goldstein JL, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Waring JP, Faigel DO. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Tringali A. Current management of postoperative complications and benign biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003;13:635-648, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Training Committee. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Training guideline for use of propofol in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:167-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kazama T, Takeuchi K, Ikeda K, Ikeda T, Kikura M, Iida T, Suzuki S, Hanai H, Sato S. Optimal propofol plasma concentration during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in young, middle-aged, and elderly patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:662-669. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Carlsson U, Grattidge P. Sedation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a comparative study of propofol and midazolam. Endoscopy. 1995;27:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koo JS, Choi JH, Jung SW, Han WS, Lee JS, Yim HJ, Jeen YT, Chun HJ, Lee HS, Lee SW. Conscious sedation with midazolam combined with propofol for colonoscopy. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;34:298-303. |

| 10. | Jung M, Hofmann C, Kiesslich R, Brackertz A. Improved sedation in diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: propofol is an alternative to midazolam. Endoscopy. 2000;32:233-238. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Keeffe EB, O’Connor KW. 1989 A/S/G/E survey of endoscopic sedation and monitoring practices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S13-S18. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Larijani GE, Gratz I, Afshar M, Jacobi AG. Clinical pharmacology of propofol: an intravenous anesthetic agent. DICP. 1989;23:743-749. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Short TG, Plummer JL, Chui PT. Hypnotic and anaesthetic interactions between midazolam, propofol and alfentanil. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lichtenstein DR, Jagannath S, Baron TH, Anderson MA, Banerjee S, Dominitz JA, Fanelli RD, Gan SI, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO. Sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:815-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Clarke AC, Chiragakis L, Hillman LC, Kaye GL. Sedation for endoscopy: the safe use of propofol by general practitioner sedationists. Med J Aust. 2002;176:158-161. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wehrmann T, Riphaus A. Sedation with propofol for interventional endoscopic procedures: a risk factor analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:368-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kongkam P, Rerknimitr R, Punyathavorn S, Sitthi-Amorn C, Ponauthai Y, Prempracha N, Kullavanijaya P. Propofol infusion versus intermittent meperidine and midazolam injection for conscious sedation in ERCP. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17:291-297. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Riphaus A, Stergiou N, Wehrmann T. Sedation with propofol for routine ERCP in high-risk octogenarians: a randomized, controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1957-1963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yusoff IF, Raymond G, Sahai AV. Endoscopist administered propofol for upper-GI EUS is safe and effective: a prospective study in 500 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vargo JJ, Zuccaro G, Dumot JA, Shermock KM, Morrow JB, Conwell DL, Trolli PA, Maurer WG. Gastroenterologist-administered propofol versus meperidine and midazolam for advanced upper endoscopy: a prospective, randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:8-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Paspatis GA, Manolaraki MM, Vardas E, Theodoropoulou A, Chlouverakis G. Deep sedation for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: intravenous propofol alone versus intravenous propofol with oral midazolam premedication. Endoscopy. 2008;40:308-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coté GA, Hovis RM, Ansstas MA, Waldbaum L, Azar RR, Early DS, Edmundowicz SA, Mullady DK, Jonnalagadda SS. Incidence of sedation-related complications with propofol use during advanced endoscopic procedures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim EH, Lee SK. Endoscopist-directed propofol: pros and cons. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Poulos JE, Kalogerinis PT, Caudle JN. Propofol compared with combination propofol or midazolam/fentanyl for endoscopy in a community setting. AANA J. 2013;81:31-36. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Cho YS, Seo E, Han JH, Yoon SM, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ. Comparison of midazolam alone versus midazolam plus propofol during endoscopic submucosal dissection. Clin Endosc. 2011;44:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | McClune S, McKay AC, Wright PM, Patterson CC, Clarke RS. Synergistic interaction between midazolam and propofol. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:240-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Reimann FM, Samson U, Derad I, Fuchs M, Schiefer B, Stange EF. Synergistic sedation with low-dose midazolam and propofol for colonoscopies. Endoscopy. 2000;32:239-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Biecker E, Huang CM S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Liu XM