Published online May 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5488

Peer-review started: September 18, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: November 16, 2014

Accepted: January 21, 2015

Article in press: January 21, 2015

Published online: May 14, 2015

Processing time: 243 Days and 23.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the outcomes of pancreas-sparing duodenectomy (PSD) with regional lymph node dissection vs pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD).

METHODS: Between August 2001 and June 2014, 228 patients with early-stage ampullary carcinoma (Amp Ca) underwent surgical treatment (PD, n = 159; PSD with regional lymph node dissection, n = 69). The patients were divided into two groups: the PD group and the PSD group. Propensity scoring methods were used to select patients with similar disease statuses. A total of 138 matched cases, with 69 patients in each group, were included in the final analysis.

RESULTS: The median operative time was shorter among the patients in the PSD group (435 min) compared with those in the PD group (481 min, P = 0.048). The median blood loss in the PSD group was significantly less than that in the PD group. The median length of hospital stay was shorter for patients in the PSD group vs the PD group. The incidence of pancreatic fistula was higher among patients in the PD group vs the PSD group. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival rates for patients in the PSD group were 83%, 70%, 44% and 73%, 61%, 39%, respectively, and these values were not different than compared with those in the PD group (P = 0.625).

CONCLUSION: PSD with regional lymph node dissection presents an acceptable morbidity in addition to its advantages over PD. PSD may be a safe and feasible alternative to PD in the treatment of early-stage Amp Ca.

Core tip: The median operative time and hospital stay were shorter among the patients in the pancreas-sparing duodenectomy (PSD) group compared with those in the pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) group. The median blood loss in the PSD group was significantly less than that in the PD group. The incidence of pancreatic fistula was higher among patients in the PD group vs the PSD group. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival rates for patients in the PSD group were not different compared with those in the PD group. These data suggest that PSD with regional lymph node dissection may be a safe and feasible alternative to PD in the treatment of early-stage ampullary carcinoma.

- Citation: Liu B, Li J, Zhang YJ, Yan LN, You SY, Lau WY, Sun HR, Yan SY, Wang ZQ. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy with regional lymph node dissection for early-stage ampullary carcinoma: A case control study using propensity scoring methods. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(18): 5488-5495

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i18/5488.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5488

The incidence of ampullary carcinoma (Amp Ca) has progressively increased over the last 30 years[1]. Compared with pancreatic carcinoma or common bile duct carcinoma, Amp Ca has an earlier appearance of obstructive symptoms, more favorable histology, and a decreased inclination towards lymphatic or perineural invasion; therefore, it is associated with a higher likelihood of resectability and a more favorable prognosis[2].

Even though pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is still considered the only possible curative treatment for patients with Amp Ca[3], the complex anatomy and common blood supply of the pancreatico-duodenal region contribute to the technical difficulties and prolonged operative stress induced by PD[4]. Compared with PD, pancreas-sparing duodenectomy (PSD) is less invasive and offers the potential to preserve the anatomical gastrointestinal passage and integrity of the pancreas for the treatment of various periampullary malignant tumors[5]. According to the principle of damage control, a human tendency can be demonstrated towards subtle organ-preserving techniques. Thus, PSD has been introduced as a treatment option and offered as an alternative to PD in select cases of Amp Ca[6,7].

Unfortunately, lymph node metastases are present in up to 28% of patients with pT1Amp Ca[8]. Thus, it is essential that PSD with regional lymph node dissection only be used in early-stage Amp Ca. Due to the uncertainty of the long-term results, the application of PSD with regional lymph node dissection in early-stage Amp Ca (pTis or pT1, N0 or N1, M0) patients remains controversial[9]. We used propensity scoring methods to investigate the prognostic differences among patients with early-stage Amp Ca who were managed by PSD with regional lymph node dissection vs PD.

From a retrospectively collected database, we identified 228 patients who underwent surgery (PD, n = 159; PSD with regional lymph node dissection, n = 69) for early-stage Amp Ca at the General Hospital of Tianjin Medical University from August 2001 to June 2014. We divided the patients with early-stage Amp Ca into two groups: a PD group and a PSD group. To reduce the presence of potential confounders in this present study, the values of the propensity scores were used to adjust for differences between the two groups. A total of 138 matched cases, with 69 patients in each group, were included in the final analysis. This study was approved by the Ethics Board at the General Hospital of Tianjin Medical University and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The registration number (ChiCTR-OCH-14005198) was issued by the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry.

Early-stage Amp Ca was defined as a carcinoma directly centered on or associated with an in situ carcinoma of the ampulla or/and papilla[3] that has not spread to the bile duct or pancreatic duct and invades the duodenal muscularis propria layer[10], as evidenced by postoperative pathology report. Cancer staging was performed using the 7th edition of the TNM staging system for ampullary carcinoma issued by the American Joint Committee on Cancer[11]. All patients underwent chest radiography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and endoscopic ultrasonography for preoperative locoregional staging. Only patients in stages pTis, pT1, N0, N1, or M0 would be considered as candidates for the PSD group. Tumors of the duodenum, bile duct, or pancreatic were excluded in this study. In the control group, these patients matched with the PSD group for demographic data, tumor type, tumor size, tumor type, and TNM classification and underwent standard PD for early-stage Amp Ca during the same period.

The multidisciplinary team of this study reviewed the following data for each patient: demographics; laboratory blood tests; contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen; magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; endoscopic ultrasonography; operative details; resection margin status; presence of lymph node metastasis; peri-operative morbidity and mortality; vital status; and date of death or last follow-up. All operative procedures were consecutively performed by a senior surgeon with expertise in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery at our institution. All pathology specimens (formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were retrieved from the archives of the pathology department) were reviewed by a pathologist. One pathologist who was blinded to the clinical and survival data re-evaluated all of the pathologic specimens and histopathologic findings.

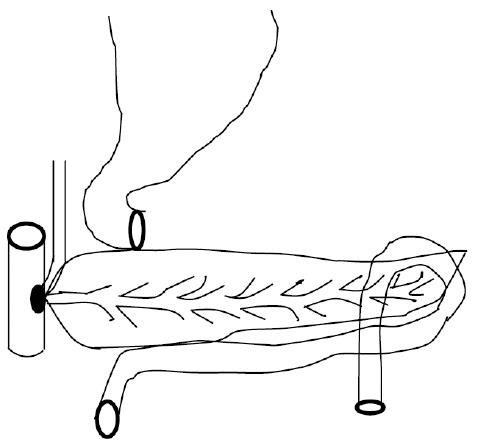

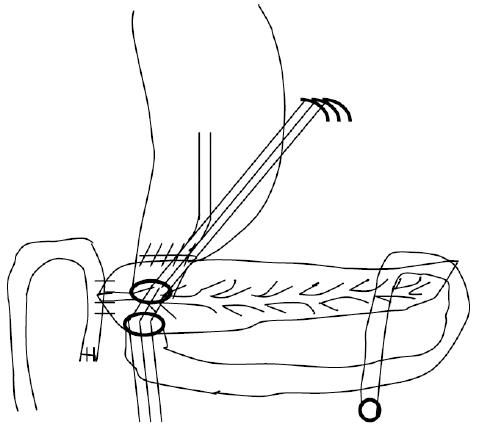

The definitions of R0 resection, R1 resection, and specific complications, such as pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying, have been described elsewhere[12-14]. The Japan Pancreatic Society (JPS) system for the numbering of lymph node stations was adopted to accurately describe the operation and pathologic assessment[15]. The technique used for standard PD and PSD with (Figures 1 and 2) regional lymph node dissection has been previously described elsewhere[16,17].

All patients who completed follow-up were monitored postoperatively with routine blood tests, tumor markers (carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen), chest radiography, endoscopic ultrasonography, and CT. Follow-up studies were performed every six months. Overall survival was defined as the time from surgical resection to death. Initial disease recurrence was determined using CT images and classified as locoregional (anastomotic site or regional or retroperitoneal lymph node) or distant (peritoneal, hepatic, or another organ) disease recurrence. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the time from surgical resection to the time when a recurrent tumor was first diagnosed[3].

To overcome the effects of patient background and to increase the robustness of this retrospective observational case-control study, matching was performed with the aim of selecting subsets of case and control groups with similar distributions of the observed covariates in this study. The data were expressed using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Continuous variables were compared by means of the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Multivariate/univariate analyses were conducted using the log-rank test to examine risk factors and associations with mortality. Survival time was censored at the date of last follow-up if death had not occurred. Survival curves were estimated using Kaplan-Meier techniques. Statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

From August 2009 to June 2014, the medical records of patients with Tis/T1 Amp Ca who underwent PSD with regional lymph node dissection or standard PD during the same study period were retrospectively reviewed. After one-to one matching using propensity score analysis, 69 pairs of patients were matched and compared. Among the propensity score-matched pairs, there were no significant differences in the demographic data or preoperative status of the patients between the two groups (detailed in Table 1). The clinical backgrounds of the two groups were thus successfully matched.

| Characteristic | PD group | PSD group | P value |

| (n = 69) | (n = 69) | ||

| Age (yr) | 58.5 (41-79) | 62.1 (39-78) | 0.765 |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 36 (52.3) | 38 (55.1) | 0.681 |

| Preoperative laboratory results | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.7 (9.0-14.3) | 11.0 (9.3-14.5) | 0.663 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 7.1 (0.9-14.8) | 7.6 (0.6-15.1) | 0.701 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 3.5 (2.3-5.6) | 3.7 (2.4-5.3) | 0.913 |

| CA19-9 (ng/mL) | 33.8 (0.1-491) | 37.1 (0.1-463) | 0.594 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 1.8 (0.1-30.2) | 2.0 (0.1-31) | 0.787 |

| Past medical history, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 21 (30.4) | 23 (33.3) | 0.604 |

| Coronary artery disease | 15 (21.7) | 13 (18.8) | 0.837 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (11.6) | 9 (13.0) | 0.694 |

| History of alcohol abuse | 6 (8.7) | 7 (10.1) | 0.668 |

| History of tobacco use | 17 (24.6) | 19 (27.5) | 0.917 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (7.2) | 4 (5.8) | 0.857 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4 (5.8) | 4 (5.8) | 0.793 |

| COPD | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 0.634 |

Intraoperative data are summarized in Table 2. The median operative time was shorter among patients in the PSD group (435 min) compared with those in the PD group (481 min, P = 0.048). The median blood loss in the PSD group was 351 mL, lower than that in the PD group (802 mL, P = 0.031). As expected, patients requiring intra-operative blood transfusions in the PSD group were fewer than those in the PD group (P = 0.027). To identify whether the patients were free of carcinoma, frozen section biopsies were performed for qualifying patients in both groups after the en block resection of the ampulla of Vater and the descending segment of the duodenum.

| Characteristic | PD group | PSD group | P value |

| (n = 69) | (n = 69) | ||

| Op. time (min) | 481 (312-798) | 435 (301-552) | 0.048 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 802 (240-1900) | 351 (150-1000) | 0.031 |

| Patients needing intraoperative blood transfusion, n (%) | 23 (33.3) | 7 (10.1) | 0.027 |

The median length of the hospital stay was shorter for patients in the PSD group (10 d) vs the PD group (18 d, P = 0.045). However, the median length of the ICU stay was not significantly different between the PSD group (3 d) and the PD group (4 d, P = 0.059). The hospital mortality rate was not significantly different between the PSD group (2.9%) and the PD group (4.3%, P = 0.081). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the reoperation rate between the PSD group (4.3%) and the PD group (7.2%, P = 0.064). Eight patients (3 in the PSD group vs 5 in the PD group) required reoperations due to abdominal/gastrointestinal bleeding associated with pancreatic leakage. Three patients undergoing PSD developed a pancreatic anastomotic leak (grade A, n = 2; grade C, n = 1), whereas 16 patients developed a pancreatic fistula (grade A, n = 4; grade B, n = 8; grade C, n = 4) after PD. The incidence of pancreatic fistula was higher among patients in the PD group (23.2%) vs the PSD group (4.3%, P = 0.037). Delayed gastric emptying was noted exclusively in the PD group (15 vs 6 in the PSD group, P = 0.045). Eight patients undergoing PD developed postoperative diabetes mellitus, whereas no cases of new-onset diabetes were observed in the PSD group (P = 0.041). There were no differences in the overall incidence of abdominal/gastrointestinal bleeding, bile leakage, wound infection, sepsis, abdominal abscess, or cardiac events between the two groups (detailed in Table 3).

| Characteristic | PD group | PSD group | P value |

| (n = 69) | (n = 69) | ||

| Hospital stay (d), median (range) | 18 (8-60) | 10 (7-26) | 0.045 |

| ICU stay (d), median (range) | 4 (2-15) | 3 (1-7) | 0.059 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.9) | 0.081 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 5 (7.2) | 3 (4.3) | 0.064 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |||

| Pancreatic leakage | 16 (23.2) | 3 (4.3) | 0.037 |

| Grade A | 4 | 2 | 0.106 |

| Grade B | 8 | 0 | 0.058 |

| Grade C | 4 | 1 | 0.217 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 15 | 6 | 0.045 |

| New onset diabetes mellitus | 8 | 0 | 0.041 |

| Bile leak | 2 | 0 | 0.678 |

| Abdominal bleeding | 9 | 5 | 0.721 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 6 | 4 | 0.661 |

| Wound infection | 5 | 2 | 0.543 |

| Sepsis | 2 | 1 | 0.608 |

| Abdominal abscess | 4 | 2 | 0.334 |

| Cardiac event | 3 | 0 | 0.329 |

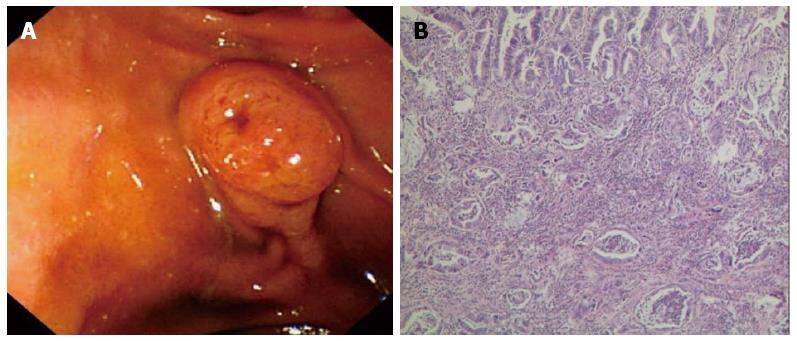

The median tumor size was not different between the patients in the PD group (3.0 cm) vs the PSD group (2.6 cm, P = 0.053). According to the 7th edition of the TNM staging system, there were 3 Tis and 66 T1 patients in the PSD group and 4 Tis and 65 T1 patients in the PD group. There were 49 N0 stage and 20 N1 stage patients in the PSD group, whereas 45 patients were N0 stage and 24 were N1 stage in the PD group. The percentages of the positive nodes/evaluated nodes were 16.7% (18/108) and 17.6% (22/125) of the patients in the PSD and PD groups (P = 0.102), respectively. The most commonly involved nodes in both study groups were the posterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes (JPS LN13), followed by the anterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes (JPS LN17). Other lymph nodes with high metastatic potential were the right-sided inferior nodes of the hepatoduodenal ligament (JPS LN12), the infrapyloric node (JPS LN6), and the nodes around the superior mesenteric artery (JPS LN14) (detailed in Table 4). Histologic findings indicated that there were 27 intestinal carcinoma, 40 pancreatobiliary carcinoma and 2 mixed type carcinoma cases in the PSD group. By contrast, there were 24 intestinal carcinoma, 42 pancreatobiliary carcinoma, and 3 mixed type carcinoma cases in the PD group (showed in Figure 3). The histologic grades did not differ between the PSD and PD groups. There were 64 R0 resections and 5R1 resections in the PSD group, compared to 63 R0 resections and 6 R1 resections in the PD group. On multivariate analysis, the factors associated with an increased risk of lymph node metastasis included tumor size ≥ 1 cm (OR = 2.3; 95%CI: 1.3-4.0) and histologic grade (OR = 3.7; 95%CI: 2.1-6.9)

| Characteristic | PD group | PSD group | P value |

| (n = 69) | (n = 69) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | 2.6 (0.6-4.7) | 0.053 |

| TNM classification: Primary tumor | |||

| Tis | 4 | 3 | 0.071 |

| T1 | 65 | 66 | 0.644 |

| TNM classification: Regional lymph nodes, n | |||

| N0 | 45 | 49 | 0.339 |

| N1 | 24 | 20 | 0.417 |

| Number of positive nodes/evaluated nodes of JPS system, n (%) | 22 (17.6) | 18 (16.7) | 0.402 |

| JPS LN6 | 16/2 | 13/2 | 0.248 |

| JPS LN8 | 10/0 | 8/0 | 0.375 |

| JPS LN12 | 20/3 | 18/3 | 0.194 |

| JPS LN13 | 39/10 | 34/8 | 0.527 |

| JPS LN14 | 12/1 | 13/1 | 0.291 |

| JPS LN17 | 28/6 | 22/4 | 0.396 |

| Histopathologic types | |||

| Intestinal carcinoma | 24 | 27 | 0.633 |

| Pancreatobiliary carcinoma | 42 | 40 | 0.597 |

| Mixed type | 3 | 2 | 0.304 |

| Histologic grade | |||

| G1 | 32 | 34 | 0.312 |

| G2 | 37 | 35 | 0.407 |

| R0 resection, n | 63 | 64 | 0.805 |

| R1 resection, n | 6 | 5 | 0.763 |

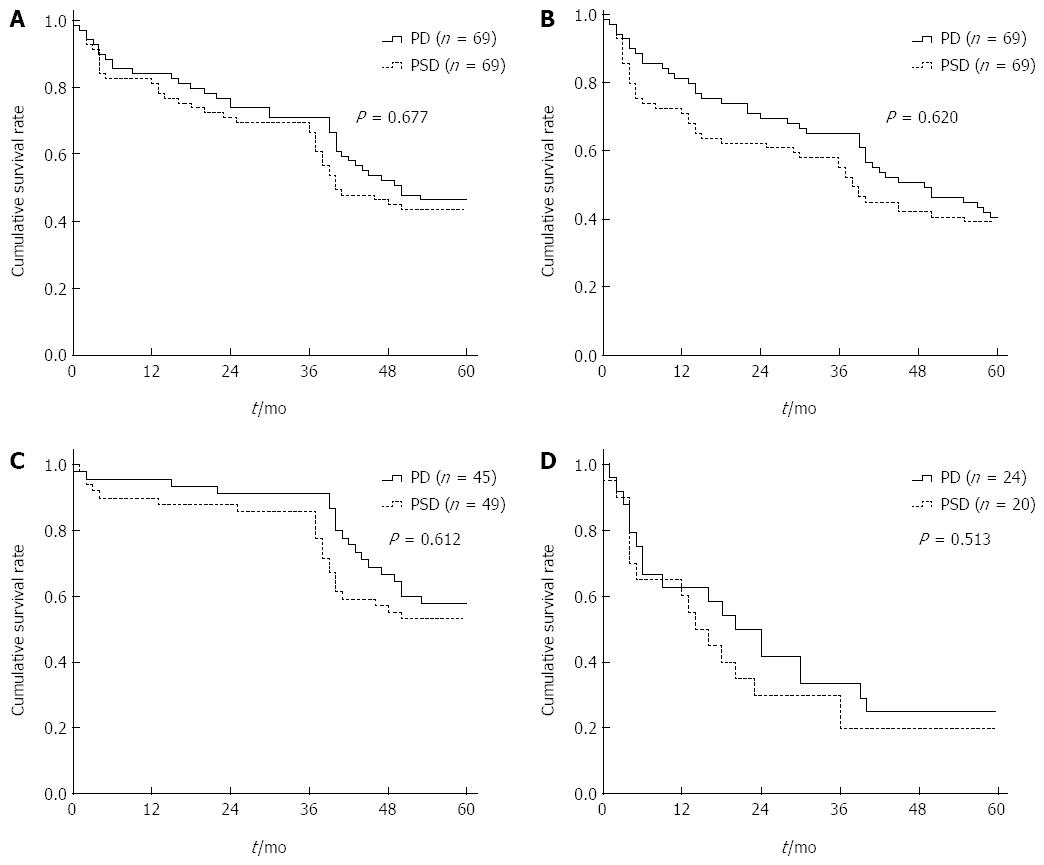

After a mean follow-up period of 45 mo (range, 4-70 mo), 16 (23.2%) of the patients developed tumor recurrence in the PSD group, compared to 14 (20.3%) in the PD group. The median time between surgery and the diagnosis of disease recurrence was 8.7 mo (range, 5.0-18.3 mo) in the PSD group and 10.2 mo (range, 5.2-15.4 mo) in the PD group. The main patterns of recurrence in these patients are shown in Table 5. Local regional recurrence was observed in 7 patients in the PSD group vs 4 in the PD group; distant recurrence was observed in 6 patients in the PSD group (hepatic 3, and lung 3) vs 4 in the PD group (hepatic 2, peritoneal 1, and lung 1). Local recurrences with distant metastases were observed in 3 patients in the PSD group (hepatic 2, and lung 1) vs 6 in the PD group (hepatic 3, peritoneal 1, and lung 2). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survivals and disease-free survivals for patients in the PSD group were 83%, 70%, 44%, and 73%, 61%, 39%, respectively, without any significant difference from the patients in the PD group (P = 0.625) (Figure 4A and B). Additionally, the median survival and 5-year survival rates for N1 patients in the PSD group were 19.8 mo and 20%, respectively, which were not different from the values among the N1 patients in the PD group (21.4 mo and 25.0%, respectively) (P > 0.05) (Figure 4D).

| Characteristic | PD (n = 69) | PSD (n = 69) | P value |

| Recurrence rate, n (%) | 14 (20.3) | 16 (23.2) | 0.427 |

| Time to recurrence (mo) | 10.2 (5.2-15.4) | 8.7 (5.0-18.3) | 0.518 |

| Type of recurrence, n | |||

| Local recurrence | 4 | 7 | 0.409 |

| Distant metastases | 4 | 6 | 0.331 |

| Local recurrence and distant metastases | 6 | 3 | 0.497 |

| Overall survival | |||

| 1 yr | 81% | 83% | 0.617 |

| 3 yr | 71% | 70% | 0.735 |

| 5 yr | 46% | 44% | 0.591 |

| Disease free survival | |||

| 1 yr | 81% | 73% | 0.704 |

| 3 yr | 65% | 61% | 0.692 |

| 5 yr | 41% | 39% | 0.679 |

Early-stage Amp Ca (pTis or pT1, N0 or N1, M0) is characterized by a tumor limited to the mucosa of the ampulla or of the sphincter of Oddi, regardless of the presence or absence of lymph node metastasis. PD represents the curative procedure of choice for the majority of patients with Amp Ca. However, high operative mortality rates (15% to 23%) and morbidity rates (24% to 60%) of PD have been reported in the 1990s and in recent studies[18]. Although PSD offers certain advantages over PD[19,20], this organ-preserving surgical procedure was mainly used for patients with periampullary adenomas[21]. The exploration of less invasive, feasible and safe surgical approaches for the treatment of early-stage Amp Ca remains an important target for clinical research.

Recently, several studies have demonstrated that PSD with regional lymph node dissection is suitable for patients with early-stage Amp Ca. However, this surgical technique is challenging due to the uncertainty of tumor clearance, recurrence, and long-term survival. Therefore, the present study sought to examine the outcomes of patients undergoing PSD with regional lymph node dissection vs PD, as well as to identify factors predictive of recurrence in patients with early-stage Amp Ca.

Although the hospital mortality, recurrence rate, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates and disease-free survival following PD and PSD with regional lymph node dissection were not significantly different (P > 0.05) in this study, the incidence of pancreatic fistula was lower among patients in the PSD group (23.2%) vs the PD group (4.3%, P = 0.037). Hospital stays were also shorter among patients in the PSD group (10 d) vs the PD group (18 d, P = 0.045). Similar to previous studies[22,23], the advantages of PSD over PD in the present study included the following: shorter surgical time, less intra-operative bleeding, less intra-operative blood transfusion, more conserved intestinal function, preservation of pancreatic tissue, and allowance for better endoscopic follow-up.

Many factors have been proven to influence survival in the early stages of Amp Ca, including R0 resection, lymph node metastases, lymphatic invasion, tumor stage, and tumor grade[24,25]. Our multivariate analysis, however, indicated that lymph node metastasis is one of the most important independent indicators predicting Amp Ca recurrence and long-term survival. Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated that lymph node metastases were present in 10%-28% of patients in the early stages of Amp Ca[8,26]. In this study, lymph node metastases were present in 17%-18% of patients with early-stage Amp Ca. Our study, which is consistent with the current literature on PSD[17,27], demonstrated that radical resection with regional lymph node dissection is required for the surgical treatment of early-stage Amp Ca. The most commonly involved nodes were the posterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes (JPS LN13), followed by the anterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes (JPS LN17), in our study group.

In conclusion, even in early stages of Amp Ca, the rate of lymph node metastases is approximately 17%-18%. Lymph node metastases are one of the most important independent indicators predicting Amp Ca recurrence and long-term survival. Thus, radical resection is required for surgical treatments at the early stages of Amp Ca. PSD with regional lymph node dissection is less invasive, feasible and safer for the treatment of early-stage Amp Ca. This procedure provides an acceptable morbidity and mortality rate for early-stage Amp Ca when compared to PD.

The outcomes of pancreas-sparing duodenectomy (PSD) with regional lymph node dissection for early-stage ampullary carcinoma (Amp Ca) remain uncertain. The aim of this study was to investigate the outcomes of PSD with regional lymph node dissection vs pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD).

Due to the uncertainty of the long-term results, the application of PSD with regional lymph node dissection in early-stage Amp Ca (pTis or pT1, N0 or N1, M0) patients remains controversial.

This is a novel study in that it addresses the median operative time and hospital stay were shorter among the patients in the PSD group compared with those in the PD group. The median blood loss in the PSD group was significantly less than that in the PD group. The incidence of pancreatic fistula was lower among patients in the PSD group vs the PD group. The overall survival and disease-free survival for patients in the PSD group were not different than those of the patients in the PD group. These data suggest that PSD with regional lymph node dissection presents an acceptable morbidity and provides advantages over PD.

PSD with regional lymph node dissection may be a safe and feasible alternative to PD in the treatment of early-stage Amp Ca.

This is an interesting study that shows the largest number of patients with early-stage ampullary carcinoma (Amp Ca) in mainland China in this study. It suggests that PSD with regional lymph node dissection is less invasive, feasible and safer for the treatment of early-stage Amp Ca. This procedure provides an acceptable morbidity and mortality rate for early-stage Amp Ca when compared to PD.

| 1. | Albores-Saavedra J, Schwartz AM, Batich K, Henson DE. Cancers of the ampulla of vater: demographics, morphology, and survival based on 5,625 cases from the SEER program. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, Pichlmayr R. Prognostic factors after resection of ampullary carcinoma: multivariate survival analysis in comparison with ductal cancer of the pancreatic head. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1686-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Narang AK, Miller RC, Hsu CC, Bhatia S, Pawlik TM, Laheru D, Hruban RH, Zhou J, Winter JM, Haddock MG. Evaluation of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy for ampullary adenocarcinoma: the Johns Hopkins Hospital-Mayo Clinic collaborative study. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagai H, Hyodo M, Kurihara K, Ohki J, Yasuda T, Kasahara K, Sekiguchi C, Kanazawa K. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy: classification, indication and procedures. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1953-1958. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Konishi M, Kinoshita T, Nakagohri T, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Ryu M. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy for duodenal neoplasms including malignancies. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:753-757. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Poves I, Burdio F, Alonso S, Seoane A, Grande L. Laparoscopic pancreas-sparing subtotal duodenectomy. JOP. 2011;12:62-65. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ahn YJ, Kim SW, Park YC, Jang JY, Yoon YS, Park YH. Duodenal-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas and pancreatic head resection with second-portion duodenectomy for benign lesions, low-grade malignancies, and early carcinoma involving the periampullary region. Arch Surg. 2003;138:162-168; discussion 168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Winter JM, Cameron JL, Olino K, Herman JM, de Jong MC, Hruban RH, Wolfgang CL, Eckhauser F, Edil BH, Choti MA. Clinicopathologic analysis of ampullary neoplasms in 450 patients: implications for surgical strategy and long-term prognosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:379-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park JS, Yoon DS, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ, Chi HS, Kim BR. Factors influencing recurrence after curative resection for ampulla of Vater carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ogawa T, Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Masu K, Ishii S. Endoscopic papillectomy as a method of total biopsy for possible early ampullary cancer. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th edition. New York: Springer-Verlag 2010; . |

| 12. | Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Chang DC, Riall TS, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Coleman J, Hodgin MB, Sauter PK. Does pancreatic duct stenting decrease the rate of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1280-1290; discussion 1290. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Yeo CJ, Barry MK, Sauter PK, Sostre S, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Cameron JL. Erythromycin accelerates gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Surg. 1993;218:229-237; discussion 237-238. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Isaji S, Kawarada Y, Uemoto S. Classification of pancreatic cancer: comparison of Japanese and UICC classifications. Pancreas. 2004;28:231-234. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Pessaux P, Varma D, Arnaud JP. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: superior mesenteric artery first approach. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:607-611. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Chen G, Wang H, Fan Y, Zhang L, Ding J, Cai L, Xu T, Lin H, Bie P. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy with regional lymphadenectomy for pTis and pT1 ampullary carcinoma. Surgery. 2012;151:510-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Arkadopoulos N, Kyriazi MA, Papanikolaou IS, Vasiliou P, Theodoraki K, Lappas C, Oikonomopoulos N, Smyrniotis V. Preoperative biliary drainage of severely jaundiced patients increases morbidity of pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a case-control study. World J Surg. 2014;38:2967-2972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Parc Y, Mabrut JY, Shields C. Surgical management of the duodenal manifestations of familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2011;98:480-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Müller MW, Dahmen R, Köninger J, Michalski CW, Hinz U, Hartel M, Kadmon M, Kleeff J, Büchler MW, Friess H. Is there an advantage in performing a pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy in duodenal adenomatosis? Am J Surg. 2008;195:741-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ramia-Angel JM, Quiñones-Sampedro JE, De La Plaza Llamas R, Gomez-Caturla A, Veguillas P. [Pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy]. Cir Esp. 2013;91:466-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Al-Sarireh B, Ghaneh P, Gardner-Thorpe J, Raraty M, Hartley M, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Complications and follow-up after pancreas-preserving total duodenectomy for duodenal polyps. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1506-1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Johnson MD, Mackey R, Brown N, Church J, Burke C, Walsh RM. Outcome based on management for duodenal adenomas: sporadic versus familial disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:229-235. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Barauskas G, Gulbinas A, Pranys D, Dambrauskas Z, Pundzius J. Tumor-related factors and patient’s age influence survival after resection for ampullary adenocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:423-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Qiao QL, Zhao YG, Ye ML, Yang YM, Zhao JX, Huang YT, Wan YL. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: factors influencing long-term survival of 127 patients with resection. World J Surg. 2007;31:137-143; discussion 144-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Beger HG, Treitschke F, Gansauge F, Harada N, Hiki N, Mattfeldt T. Tumor of the ampulla of Vater: experience with local or radical resection in 171 consecutively treated patients. Arch Surg. 1999;134:526-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Duffy JP, Hines OJ, Liu JH, Ko CY, Cortina G, Isacoff WH, Nguyen H, Leonardi M, Tompkins RK, Reber HA. Improved survival for adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: fifty-five consecutive resections. Arch Surg. 2003;138:941-948; discussion 948-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Bradley EL, Sugiyama H S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM