Published online May 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5320

Peer-review started: November 24, 2014

First decision: December 11, 2014

Revised: January 7, 2015

Accepted: February 11, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: May 7, 2015

Processing time: 171 Days and 11.7 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the association of metabolic syndrome (MS) and colorectal cancer and adenomas in a Western country, where the incidence of MS is over 27%.

METHODS: This was a prospective study between March 2013 and March 2014. MS was diagnosed according to the National Cholesterol Education Program-ATP III. Demographic characteristics, anthropometric measurements, metabolic risk factors, and colonoscopic pathologic findings were assessed in patients with MS (group 1) who underwent routine colonoscopy at our department. This data was compared with consecutive patients without metabolic syndrome (group 2), with no differences regarding sex and age. Patients with incomplete colonoscopy, family history, or past history of colorectal neoplasm were excluded. Informed consent was obtained and the ethics committee approved this study. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test and χ2 test, with a P value ≤ 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

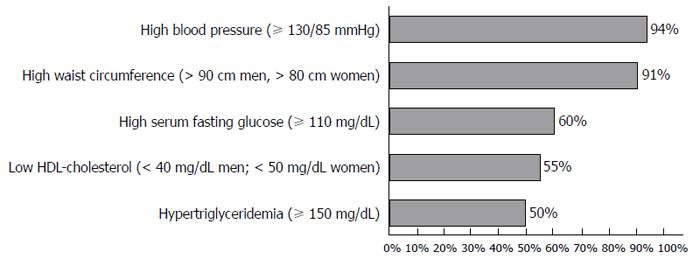

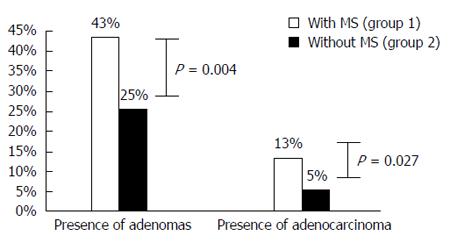

RESULTS: Of 258 patients, 129 had MS; 51% males; mean-age 67.1 years (50-87). Among the MS group, 94% had high blood pressure, 91% had increased waist circumference, 60% had diabetes, 55% had low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, 50% had increased triglyceride level, and 54% were obese [body mass index (BMI) 30 kg/m2]. 51% presented 4 criteria of MS. MS was associated with increased prevalence of adenomas (43% vs 25%, P = 0.004) and colorectal cancer (13% vs 5%, P = 0.027), compared with patients without MS. MS was also positively associated with multiple (≥ 3) adenomas (35% vs 9%, P = 0.024) and sessile adenomas (69% vs 53%, P = 0.05). No difference existed between location (P = 0.086), grade of dysplasia (P = 0.196), or size (P = 0.841) of adenomas. In addition, no difference was found between BMI (P = 0.078), smoking (P = 0.146), alcohol consumption (P = 0.231), and the presence of adenomas.

CONCLUSION: MS is positively associated with adenomas and colorectal cancer. However, there is not enough information in western European countries to justify screening in patients with MS. To our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated this association in Portuguese patients.

Core tip: In light of recent findings on the association between insulin resistance and the development of colorectal malignancies, it is worthwhile to investigate whether metabolic syndrome (MS) is correlated to an increased number of colorectal neoplasms. However, few studies have been performed regarding the relationship between MS, colorectal adenomatous polyps, and cancer in European countries. With this study, we aimed to investigate the association between MS and colorectal neoplasms, as well as obesity, smoking and alcohol consumption, in a Portuguese population. In our patients, MS was positively associated with colorectal cancer and adenomas.

- Citation: Trabulo D, Ribeiro S, Martins C, Teixeira C, Cardoso C, Mangualde J, Freire R, Gamito &, Alves AL, Augusto F, Oliveira AP, Cremers I. Metabolic syndrome and colorectal neoplasms: An ominous association. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(17): 5320-5327

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i17/5320.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5320

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Europe, accounting for 13% of all new cases, and is the second most common cause of cancer death[1]. In the United States, it is the third most common cancer, accounting for 9% of all cancer cases and deaths[2].

In spite of the dramatic advances in understanding the genetic changes related to progression from adenomatous polyp to cancer, compelling evidence supports the strong role of environmental factors in carcinogenesis. Epidemiological results from countries with a high incidence of CRC have shown that lifestyle factors are associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer; including obesity, alcohol, physical inactivity, and a westernized diet[3-5].

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is defined by a cluster of risk factors, which include abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, raised blood pressure, elevated triglyceride levels, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol levels[6]. It has become a major public health problem in several countries due to increasing obesity and sedentary lifestyles. In Portugal, its prevalence is estimated at 27.5%[7]. There has been growing recognition of the importance of this syndrome not only as an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, but also for chronic diseases, including gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, and colorectal adenomas[8]. Several investigators have showed that MS is associated with colorectal adenomas in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwan populations[8-15]. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio, which are indicators of abdominal obesity, were also strongly associated with colorectal cancer risk in a prospective European study[16]. A meta-analysis has also confirmed the association between obesity and colorectal cancer risk[17].

In light of the growing magnitude of MS in public health and recent findings on the association between insulin resistance and development of colorectal malignancies, it is worthwhile to investigate whether MS and its major components are correlated to an increased number of colorectal neoplasms. However, few studies have been carried out regarding the relationship between MS, colorectal adenomatous polyps, and cancer in European countries[16,18]. Since the bulk of data concerning MS and colorectal neoplasms comes from Asian and Pacific countries, and is related to their increasing colorectal cancer prevalence, these conclusions may not be applicable to other populations, such as those in south western European countries. In Portugal, despite its Mediterranean nature and Atlantic location, the incidence of CRC has been increasing as a result of obesity and westernization of lifestyle. CRC is the second most common cause of cancer death in Portugal, being responsible for 9 to 10 deaths daily, with a global survival rate of 50% at 5 years[19].

With this study, we aimed to investigate the association between MS and colorectal neoplasms, as well as obesity, smoking and alcohol consumption, in a Portuguese population.

We performed a prospective study on a series of patients who underwent colonoscopy at the Gastroenterology Department of Hospital de São Bernardo, at Centro Hospitalar de Setúbal, Portugal, between March 2013 and March 2014. This study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee and National Data Protection Committee. Informed consent was obtained for all patients.

Demographic characteristics, anthropometric measurements, laboratory values, metabolic risk factors, and colonoscopy pathologic findings were assessed in patients with MS (group 1). This data was compared with consecutive patients without metabolic syndrome (group 2), with no statistically significant differences regarding sex and age.

The data was collected from a standardized questionnaire performed at medical consultation and included: sex; age; height (m); weight (kg); body mass index (BMI), kg/m2; waist circumference (cm) measured 1 cm above the umbilicus at minimal respiration; medical history of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia; smoking and alcohol (> 40 g/d) consumption habits; history of adenomas or CRC; family history of adenomas or CRC; fasting glucose, triglyceride, and HDL cholesterol levels determined in laboratory analysis prior to the examination; blood pressure levels (at least 2 determinations in left arm, with patient in a sitting position). Obesity was defined as having BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

MS was diagnosed according to the National Cholesterol Education Program-ATP III[6] and defined if three or more of the following criteria were satisfied: (1) waist circumference > 90 cm in men and > 80 cm in women; (2) hypertriglyceridemia ≥ 150 mg/dL; (3) low HDL cholesterol, < 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women; (4) high blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg systolic or ≥ 85 mmHg diastolic; and (5) high serum fasting glucose ≥ 110 mg/dL.

We performed colonoscopy that reached at least the cecum and described the presence of CRC and the colonoscopic features of polyps, including the location, size, number, and morphology of adenomas, as well as its pathological features. The location of the colorectal neoplasms was divided into the proximal colon (including the cecum, ascending colon and proximal transverse colon) and the distal colon (including distal transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). The size of adenomas was classified into < 5, 5-9, and ≥ 10 mm (the largest size was used for multiple adenomas). The number of adenomas was classified into 1, 2, and ≥ 3 adenomas. The morphology was classified into sessile or pedunculated. Pathological features of adenomas were classified as low-grade or high-grade dysplasia.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of colon disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease, adenomas, or CRC; (2) family history of adenomas or CRC; (3) a colonoscopy within the previous 5 years; (4) incomplete colonoscopy; and (5) poor bowel preparation.

Statistical analysis was performed with χ2 test for comparison of discrete variables and Student’s t-test test for comparison of continuous variables. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 258 patients were included. Fifty-one per cent were men, with a mean age of 66 years (50-87 years). One hundred and twenty nine patients were included in each group (group 1 - with MS; group 2 - without MS), with no difference in sex and mean age.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of each component of MS in group 1. Ninety-four per cent of patients had elevated blood pressure and 91% had increased waist circumference.

In group 1, obesity (defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was present in 54% of patients, smoking habits were present in 31%, and alcohol consumption of > 40 g/d was present in 29% of patients. The majority of patients (51%) had 4 criteria of MS, with 29% having 5 criteria and 20% having 3 criteria.

Patients with MS (group 1) had more adenomas (43%) than patients without MS (group 2%-25%), which was statistically significant (P = 0.004). Moreover, group 1 patients had a superior prevalence of CRC than group 2 patients (13% vs 5%, P = 0.027) (Figure 2).

The analyses conducted according to location, size, number, appearance, and grade of dysplasia are shown in Table 1. A positive association with metabolic syndrome was observed for multiple adenomas (≥ 3) (35% vs 9%, P = 0.024) and sessile adenomas (69% vs 53%, P = 0.05). Moreover, an association with MS was observed for large adenomas (≥ 10 mm), as well as proximally located and synchronous adenomas (both proximal and distal colon), but this was not statistically significant.

| Adenomas | With MS (group 1) | Without MS (group 2) | P value |

| Size | |||

| < 5 mm | 20% | 25% | 0.756 |

| 5-9 mm | 25% | 22% | 0.841 |

| ≥ 10 mm | 55% | 53% | 0.822 |

| Grade of dysplasia | |||

| High grade | 81% | 94% | 0.196 |

| Low grade | 19% | 6% | 0.267 |

| Location | |||

| Proximal colon | 28% | 22% | 0.078 |

| Distal colon | 46% | 69% | 0.086 |

| Both | 26% | 9% | 0.065 |

| Number | |||

| 1 | 44% | 69% | 0.076 |

| 2 | 22% | 22% | 1.000 |

| ≥ 3 | 35% | 9% | 0.024 |

| Appearance | |||

| Sessile | 69% | 53% | 0.050 |

| Pedunculated | 11% | 40% | 0.061 |

| Both | 20% | 7% | 0.059 |

In addition, CRC was more prevalent in the distal colon (12% in group 1 vs 6 % in group 2, P = 0.026).

Table 2 shows the association found between MS and other cumulative risk factors for colorectal neoplasms: alcohol consumption, smoking, and obesity. In fact, patients with a history of alcohol consumption had more colorectal adenomas (33% vs 30%, P = 0.231) and adenocarcinoma (32% vs 24%, P = 0.102), than those without. However, this was not statistically significant. In addition, smokers had more adenomas (33% vs 26%, P = 0.146) and adenocarcinoma (30% vs 24%, P = 0.087) than non-smokers; this relation was also not significant. This relationship was found when we compared obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) with non-obese patients (BMI < 30 kg/m2): 30% vs 24% for adenomas (P = 0.078); 26% vs 20% for adenocarcinoma (P = 0.065).

| With MS (group 1) | Without MS (group 2) | P value | |

| Adenomas | |||

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes | 33% | 30% | 0.231 |

| No | 67% | 70% | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 33% | 26% | 0.146 |

| No | 67% | 74% | |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | |||

| Yes | 30% | 24% | 0.078 |

| No | 70% | 76% | |

| Adenocarcinoma | |||

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes | 32% | 24% | 0.102 |

| No | 68% | 76% | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 30% | 24% | 0.087 |

| No | 70% | 76% | |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | |||

| Yes | 26% | 20% | 0.065 |

| No | 74% | 80% | |

MS is becoming increasingly common worldwide because of the epidemic of obesity and sedentary lifestyles.

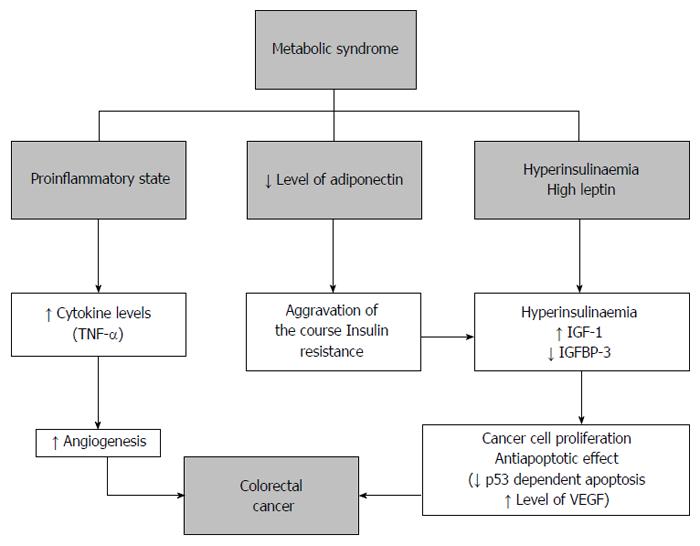

The biological plausibility of the association between MS and CRC may be mediated by dysregulation of growth signals [including insulin, insulin growth factor I (IGF-I), downstreaming signaling pathways, and adipokines], cytokines, and vascular integrity factors, thereby contributing to cancer-related processes[20]. Several authors described the role of hyperinsulinemia, IGF-I, and hyperleptinemia in the association between adiposity and CRC[20-23] (Figure 3). A common pathway has also been suggested, in which these factors increase PI3K/Akt activity, which in turn regulates downstream targets, leading to reduced apoptosis, increased cell proliferation and survival, and promotes the cell cycle[24]. In addition, a recent paper reports that, among adipocyte-secreted hormones, the most relevant to colorectal tumorigenesis are adiponectin, leptin, resistin, and ghrelin. All these molecules have been involved in cell growth, proliferation, and tumor angiogenesis, and their expression changes from normal colonic mucosa to adenoma and adenocarcinoma[25].

In our study, although a trend was observed, we found no significant association between CRC, MS, and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. The association between waist circumference and CRC risk has been generally more consistent than for BMI[15-18]. In fact, abdominal obesity has a higher risk for colon cancer than BMI, because the former reflects visceral fat deposition, which is associated with insulin resistance and higher circulating levels of IGF-I, as described above[26]. Women tend to accumulate less visceral abdominal fat than men, which may explain the gender differences in the association between obesity and risk of CRC[15,21]. There are several studies that have provided evidence that obesity was associated with CRC. These studies showed a significant positive association between obesity and CRC, although the effect was relatively modest, with an increased risk of about 1.5 to 3 times[26,27]. A meta-analysis of 6 studies found a 3% increase (95%CI: 2%-4%) in the risk of CRC per one unit increase in BMI. A meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70000 cases reported a dose-response relationship between BMI and CRC; a 5-unit increase in BMI was related to an increased risk of colon cancer in both men (RR = 1.30) and women (RR = 1.12). In addition, obesity has been more closely associated with CRC in men than in women[17]. In a 14-year multicentric cohort study, the authors reported a positive association between MS and CRC in men, but not in women[28]. A recent meta-analysis showed a 19% increase in colorectal cancer risk in individuals with a higher BMI or increased waist circumference; however, overweight and obese patients were pooled together[18].

It is well-documented that diabetes contributes to incidence and mortality of CRC. In a Korean prospective study, the authors reported that higher fasting blood sugar levels (≥ 140 mg/d) increased the risk of all types of cancer by up to 1.29 times[29,30]. A meta-analysis with 29 studies indicated an increased risk of CRC in type 2 diabetes patients (OR = 1.29 for men and 1.34 for women)[31]. Furthermore, several large-scale prospective studies have provided evidence that diabetes was associated with CRC[17,18]. A recent study investigated the association between markers of glucose metabolism, MS, and the presence of colorectal adenomas in South Korea. The authors concluded that increasing levels of glucose, insulin resistance, hemoglobin A1c, and C-peptide are significantly associated with the prevalence of adenomas[32].

Contrary to obesity and diabetes, the role of hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low-HDL cholesterol in CRC is poorly investigated. The results for studies that have examined hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia in relation to risk of CRC have been inconsistent[18], although some recent large prospective studies reported a significant association with high triglyceride levels[33,34]. However, according to a more recent meta-analysis, neither high triglyceride nor low HDL-cholesterol levels were associated with colorectal cancer risk[18]. A retrospective cohort study revealed that hypertension is an important predictor of recurrent colorectal adenoma after screening colonoscopy with adenoma polypectomy[35].

In our study, we focused on the associations not only in MS and CRC, but also in colorectal adenomas, which is a premalignant lesion that develops into CRC via the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. In our population, MS was associated with colorectal adenomas (P = 0.004) and CRC (P = 0.027), which is in agreement with previous studies. Moreover, we found that this association is significant for multiple (≥ 3) lesions (P = 0.024).

There are few studies that have examined the relation between MS and colorectal adenomas. Wang et al[9] showed that MS was associated with rectosigmoid adenomas; moreover, when the individual components of MS were examined separately, BMI and hypertriglyceridemia were associated with the age- and sex-adjusted OR of rectosigmoid adenomas (OR = 1.32; 95%CI: 1.05-1.66 and OR = 1.33; 95%CI: 1.09-1.63, respectively). Said study had several limitations: only adenomas at the rectosigmoid (not at the entire colon) were examined, only BMI (not the waist circumference) was measured, and there was no data on smoking or alcohol consumption. Another study showed that MS was associated with a moderately increased risk of colorectal adenoma with an OR of 1.48 (95%CI: 1.13-1.93)[11]. An increased risk was more evident for the proximal colon than for distal colon adenomas, and this was almost exclusively observed for large polyps (≥ 5 mm). This study also had several limitations: firstly, all subjects were male and secondly, data on lifestyle habits were not collected. A study by Kim et al[12] had methodological advantages: they included both male and female patients, total colonoscopy was performed, and lifestyle factors related to MS (including smoking and alcohol consumption) were collected. In this large Korean cross-sectional study, an increased risk of colorectal adenoma was associated with MS, particularly for proximal lesions, multiple adenomas, and advanced adenomas. The authors also found that only waist circumference was associated with the development of colon adenomas when the individual components of MS were analyzed separately on multiple logistic regression analyses[12]. Lee et al[36] reported that adenomatous polyps were significantly associated with increased BMI, and that subjects with even one component of MS had a significantly higher risk for developing adenomatous polyps compared to those subjects without any such components. In a Korean study by Pyo et al[14] showed that subjects with a high BMI and high levels of triglycerides and fasting blood glucose have an increased prevalence of developing colorectal adenomas. A recent study of a Chinese population revealed that an increased likelihood of colorectal adenoma was associated with MS. Central obesity and dyslipidemia were independently increased for colorectal adenoma risk[10].

The role played by each single component of MS on CRC risk is still unclear, as is whether the risk associated with the full syndrome is greater than the sum of its parts. Defining the risk conveyed by any single component, as compared with that of the full syndrome, may help with choosing the best way for identifying individuals at risk for CRC. In addition, the association between MS and CRC death has never been extensively investigated. A recent meta-analysis of 17 studies reported that MS was associated with an increased risk of CRC incidence and mortality in both sexes[18]. The risk estimates changed little depending on the type of study, cancer site, populations, or definition of the syndrome. Moreover, the risk estimates for any single factor of the syndrome were significant for higher values of BMI/waist, hyperglycemia, and higher blood pressure[18].

Alcohol is one of the well-established risk factors for development of CRC[37]. After oral ingestion of alcohol, acetaldehyde can accumulate locally in the colon through the microbial oxidation of alcohol, resulting in tissue injury, DNA damage, and a decrease in free radical scavengers[37]. Another mechanism of alcohol-related carcinogenesis is its interaction with retinoids[38]. Bardou et al[39] reported that excessive alcohol intake (> 50 g/d) is a risk factor for the development of adenoma with high-grade dysplasia and colorectal cancer. Moreover, Maekawa et al[38] found that excessive alcohol intake might be an independent risk factor for synchronous CRC. Our study tried to evaluate an association between excessive alcohol intake and colorectal neoplasms, but the results for this were not statistically significant. Several limitations may explain this fact: the relatively small number of patients and a lack of data concerning drinking duration, cumulative alcohol intake, and the types of alcoholic beverages consumed.

It has also been reported that smoking is associated with increased risk of CRC or colorectal adenoma, but this association is observable only in studies with adequately long reference periods[40,41]. This suggests that the putative causal role of smoking is limited in earlier stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. In our study, smoking was not found to be associated with colorectal cancer or adenomas. Again, the relatively small number of patients may explain this finding.

In our population, MS was associated with adenomas and CRC. Among the single components of the syndrome, the best evidence from the literature is the association between hyperglycemia and increased waist circumference. Based on these findings, we may speculate that these factors are the major components of the association between MS cluster and colorectal neoplasms.

Patients may need special attention for motivating them to undertake appropriate colorectal screening. Recommendations for CRC screening in patients with MS may need to be different from the average risk population; this is based on the heads-up data concerning the relationship between MS and colorectal neoplasms. However, there is not enough information in western European countries to justify screening in patients with this syndrome.

To our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated this association in Portuguese patients. Results should be replicated in other Western countries with high incidences of MS. In the meantime, it is never too late to implementing healthy lifestyle changes which can help combat MS and, thus, CRC.

There has been a growing recognition of metabolic syndrome (MS) as an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and malignancies, including colorectal cancer (CRC). In Portugal, this is the second most common cause of cancer death.

Epidemiological results from countries with a high incidence of CRC have shown that lifestyle factors (including obesity, alcohol, smoking, physical inactivity, and a westernized diet) correlate with an increased risk of CRC. Several investigators have showed that MS is associated with colorectal cancer and adenomas in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwan populations.

Few studies have been done regarding the relationship between MS and colorectal neoplasms in European countries. Since the bulk of data concerning this subject comes from Asian and Pacific countries and is related to their increasing colorectal cancer prevalence, these conclusions may not be applicable to western European countries. The authors aimed to investigate the association between MS and colorectal neoplasms, as well as obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, in a Portuguese population. No previous study has evaluated this association in Portuguese patients.

MS is positively associated with colorectal cancer and adenomas. Recommendations for CRC screening in patients with MS may need to be different from the average risk population, with respect to this relationship. However, there is not enough information in European countries to justify screening in patients with this syndrome. Results should therefore be replicated in other countries. Healthy life-style modifications are worthwhile.

It is very well-written and elaborately justified. Both the abstract and the main body of the manuscript are very nicely written and very explanatory. This manuscript deals with a very interesting issue: the association of metabolic syndrome to colorectal adenomas and colorectal cancer.

| 1. | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. Assessed on 8 Oct 2014. European: OECD Publishing 2014; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures. Atlanta, 2012. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/allcancerfactsfigures/index. |

| 3. | Chung YW, Han DS, Park YK, Son BK, Paik CH, Lee HL, Jeon YC, Sohn JH. Association of obesity, serum glucose and lipids with the risk of advanced colorectal adenoma and cancer: a case-control study in Korea. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:668-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Speizer FE. Relation of meat, fat, and fiber intake to the risk of colon cancer in a prospective study among women. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1664-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 840] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bostick RM, Potter JD, Kushi LH, Sellers TA, Steinmetz KA, McKenzie DR, Gapstur SM, Folsom AR. Sugar, meat, and fat intake, and non-dietary risk factors for colon cancer incidence in Iowa women (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:38-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20476] [Cited by in RCA: 20976] [Article Influence: 839.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Fiuza M, Cortez-Dias N, Martins S, Belo A. Síndrome Metabólica em Portugal: Prevalência e Implicações no Risco Cardiovascular - Resultados do Estudo VALSIM. Rev Port Cardiol. 2008;12:1495-1529. |

| 8. | Cremers MI. Metabolic syndrome, synchronous gastric and colorectal neoplasms: an ominous triad. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1411-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang YY, Lin SY, Lai WA, Liu PH, Sheu WH. Association between adenomas of rectosigmoid colon and metabolic syndrome features in a Chinese population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1410-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu CS, Hsu HS, Li CI, Jan CI, Li TC, Lin WY, Lin T, Chen YC, Lee CC, Lin CC. Central obesity and atherogenic dyslipidemia in metabolic syndrome are associated with increased risk for colorectal adenoma in a Chinese population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:51. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Morita T, Tabata S, Mineshita M, Mizoue T, Moore MA, Kono S. The metabolic syndrome is associated with increased risk of colorectal adenoma development: the Self-Defense Forces health study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim JH, Lim YJ, Kim YH, Sung IK, Shim SG, Oh SO, Park SS, Yang S, Son HJ, Rhee PL. Is metabolic syndrome a risk factor for colorectal adenoma? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1543-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hu NC, Chen JD, Lin YM, Chang JY, Chen YH. Stepwise relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and risk of colorectal adenoma in a Taiwanese population receiving screening colonoscopy. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011;110:100-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pyo JH, Kim ES, Chun HJ, Keum B, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Kim CD, Ryu HS, Kim YH, Lee JE. Fasting blood sugar and serum triglyceride as the risk factors of colorectal adenoma in korean population receiving screening colonoscopy. Clin Nutr Res. 2013;2:34-41. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Harima S, Hashimoto S, Shibata H, Matsunaga T, Tanabe R, Terai S, Sakaida I. Correlations between obesity/metabolic syndrome-related factors and risk of developing colorectal tumors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:733-737. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Pischon T, Lahmann PH, Boeing H, Friedenreich C, Norat T, Tjønneland A, Halkjaer J, Overvad K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC. Body size and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:920-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:556-565. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Rafaniello C, Panagiotakos DB, Giugliano D. Colorectal cancer association with metabolic syndrome and its components: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2013;44:634-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Direcção Geral de Saúde. Portugal - Doenças Oncológicas em números - 2013. Assessed on 6 Nov 2014. Available from: http://www.dgs.pt. |

| 20. | Hursting SD, Hursting MJ. Growth signals, inflammation, and vascular perturbations: mechanistic links between obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cancer. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1766-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ho GY, Wang T, Gunter MJ, Strickler HD, Cushman M, Kaplan RC, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Xue X, Rajpathak SN, Chlebowski RT. Adipokines linking obesity with colorectal cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3029-3037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: a review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2001;131:3109S-3120S. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Muhidin SO, Magan AA, Osman KA, Syed S, Ahmed MH. The relationship between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and colorectal cancer: the future challenges and outcomes of the metabolic syndrome. J Obes. 2012;2012:637538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang XF, Chen JZ. Obesity, the PI3K/Akt signal pathway and colon cancer. Obes Rev. 2009;10:610-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Riondino S, Roselli M, Palmirotta R, Della-Morte D, Ferroni P, Guadagni F. Obesity and colorectal cancer: role of adipokines in tumor initiation and progression. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5177-5190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Giorgino F, Laviola L, Eriksson JW. Regional differences of insulin action in adipose tissue: insights from in vivo and in vitro studies. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;183:13-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625-1638. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Murphy TK, Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Kahn HS, Thun MJ. Body mass index and colon cancer mortality in a large prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:847-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ahmed RL, Schmitz KH, Anderson KE, Rosamond WD, Folsom AR. The metabolic syndrome and risk of incident colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:28-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jee SH, Ohrr H, Sull JW, Yun JE, Ji M, Samet JM. Fasting serum glucose level and cancer risk in Korean men and women. JAMA. 2005;293:194-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 682] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Krämer HU, Schöttker B, Raum E, Brenner H. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis on sex-specific differences. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1269-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rampal S, Yang MH, Sung J, Son HJ, Choi YH, Lee JH, Kim YH, Chang DK, Rhee PL, Rhee JC. Association between markers of glucose metabolism and risk of colorectal adenoma. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:78-87.e3. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Borena W, Stocks T, Jonsson H, Strohmaier S, Nagel G, Bjørge T, Manjer J, Hallmans G, Selmer R, Almquist M. Serum triglycerides and cancer risk in the metabolic syndrome and cancer (Me-Can) collaborative study. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ulmer H, Borena W, Rapp K, Klenk J, Strasak A, Diem G, Concin H, Nagel G. Serum triglyceride concentrations and cancer risk in a large cohort study in Austria. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1202-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lin CC, Huang KW, Luo JC, Wang YW, Hou MC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chan WL. Hypertension is an important predictor of recurrent colorectal adenoma after screening colonoscopy with adenoma polypectomy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77:508-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lee GE, Park HS, Yun KE, Jun SH, Kim HK, Cho SI, Kim JH. Association between BMI and metabolic syndrome and adenomatous colonic polyps in Korean men. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:1434-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, Corrao G. A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1700-1705. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Maekawa SJ, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Kuroda K, Tamura T, Kuroda Y, Kasuga M. Excessive alcohol intake enhances the development of synchronous cancerous lesion in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bardou M, Montembault S, Giraud V, Balian A, Borotto E, Houdayer C, Capron F, Chaput JC, Naveau S. Excessive alcohol consumption favours high risk polyp or colorectal cancer occurrence among patients with adenomas: a case control study. Gut. 2002;50:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Kearney J, Willett WC. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of colorectal adenoma and colorectal cancer in U.S. men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:183-191. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Knekt P, Hakama M, Järvinen R, Pukkala E, Heliövaara M. Smoking and risk of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:136-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Gao F, Vallianou NG S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Wang CH