Published online Apr 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3994

Peer-review started: September 1, 2014

First decision: September 15, 2014

Revised: October 25, 2014

Accepted: January 8, 2015

Article in press: January 8, 2015

Published online: April 7, 2015

Processing time: 219 Days and 17 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the impact of reporting bowel preparation using Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) in clinical practice.

METHODS: The study was a prospective observational cohort study which enrolled subjects reporting for screening colonoscopy. All subjects received a gallon of polyethylene glycol as bowel preparation regimen. After colonoscopy the endoscopists determined quality of bowel preparation using BBPS. Segmental scores were combined to calculate composite BBPS. Site and size of the polyps detected was recorded. Pathology reports were reviewed to determine advanced adenoma detection rates (AADR). Segmental AADR’s were calculated and categorized based on the segmental BBPS to determine the differential impact of bowel prep on AADR.

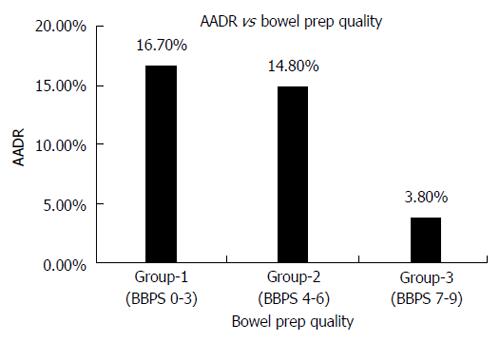

RESULTS: Three hundred and sixty subjects were enrolled in the study with a mean age of 59.2 years, 36.3% males and 63.8% females. Four subjects with incomplete colonoscopy due BBPS of 0 in any segment were excluded. Based on composite BBPS subjects were divided into 3 groups; Group-0 (poor bowel prep, BBPS 0-3) n = 26 (7.3%), Group-1 (Suboptimal bowel prep, BBPS 4-6) n = 121 (34%) and Group-2 (Adequate bowel prep, BBPS 7-9) n = 209 (58.7%). AADR showed a linear trend through Group-1 to 3; with an AADR of 3.8%, 14.8% and 16.7% respectively. Also seen was a linear increasing trend in segmental AADR with improvement in segmental BBPS. There was statistical significant difference between AADR among Group 0 and 2 (3.8% vs 16.7%, P < 0.05), Group 1 and 2 (14.8% vs 16.7%, P < 0.05) and Group 0 and 1 (3.8% vs 14.8%, P < 0.05). χ2 method was used to compute P value for determining statistical significance.

CONCLUSION: Segmental AADRs correlate with segmental BBPS. It is thus valuable to report segmental BBPS in colonoscopy reports in clinical practice.

Core tip: Bowel preparation quality determines the yield of colonoscopy. Most endoscopists continue to use the subjective systems of reporting bowel preparation. Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) helps to understand segment-specific risks for missed pathology based on the degree of bowel cleanliness. Our study showed that segmental Advanced Adenoma detection rate correlate with segmental BBPS. Segmental reporting will help in careful examination during repeat colonoscopy of segments with poor or sub-optimal BBPS on previous colonoscopy, in determining appropriate surveillance interval and the procedure for surveillance and in determining appropriate interventions to improve bowel preparation for colonoscopy in future.

- Citation: Jain D, Momeni M, Krishnaiah M, Anand S, Singhal S. Importance of reporting segmental bowel preparation scores during colonoscopy in clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(13): 3994-3999

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i13/3994.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3994

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer related death in the United States[1]. It has been postulated that with increase in colorectal screening rates, risk reduction and availability of newer chemotherapeutic agents will likely reduce the colorectal cancer mortality rates in the United States by 50% by 2020[2]. Five year survival rates for colorectal cancer survival can be highly dependent upon stage of cancer at diagnosis, and can range from 90% for cancers detected at the localized stage; 70% for regional; to 10% for people with metastatic cancer[3,4].

Multiple risk reduction, prevention and early detection strategies have led to declining rates in colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality[5]. Colonoscopy is the only test which can target prevention through the detection and removal of adenomatous polyps. Removal of polyps during colonoscopy has been shown to have predominantly indirect, but convincing evidence in prevention of CRC[6-8]. Bowel preparation is an important factor that determines the yield of colonoscopy and suboptimal preparation is associated with missed lesions[9]. Bowel preparation should be tolerable, effective without any side effects or changes in colonic mucosa[10-12]. Unfortunately, most of the currently available bowel preparations have some limitations[11-13].

Colonoscopies with suboptimal bowel prep quality are likely to have higher rates of missed lesions and there is a dire need for uniform and more efficient reporting of bowel preparation during colonoscopies. Interventions to increase bowel preparation quality utilizing visual aids (cartoons and photographs), simplified written materials and in-person and telephone counseling have resulted in mixed findings, but show promise in certain populations[14,15].

The Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) score was developed by Boston Medical Centre section of gastroenterology to provide a standardized score to rate the quality of bowel preparation during colonoscopy which can be used for clinical practice, quality assurance and outcome research in colonoscopy[16]. Three segments of colon are given a rating based on its cleanliness and the three section scores are added together for a BBPS score[16]. The scale is valid and demonstrates good inter and intra-rater reliability[16].

The efficiency of colonoscopy as a CRC screening method depends on the quality of bowel preparation. The interpretation of colonoscopy results depends on looking at the bowel preparation in addition to other findings. It is common for endoscopists to use the subjective systems of reporting bowel preparation which have high inter-observer variability. This study was designed to evaluate the impact of reporting bowel preparation using Boston Bowel Preparation Scale in clinical practice.

To determine advanced adenoma detection rate (AADR) in relation to segmental and composite BBPS’s during colonoscopy.

The study was a prospective observational cohort study conducted at an urban teaching hospital. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Consecutive patients presenting for average risk screening colonoscopy were enrolled in the study. Subjects having colonoscopy for evaluation of symptoms and personal history of colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or colon surgery for any reason were excluded. Patients who were unable to comply with the preparation instructions were excluded.

All subjects received clear liquid diet the day before colonoscopy and a gallon of polyethylene glycol as bowel preparation the evening prior to colonoscopy.

Study was an observational study and no intervention or deviation from standard practice protocols for patients were done for the study purposes. All subjects were asked questions to determine that they met inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation in study. All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed verbal consent prior to study enrolment. All colonoscopies were performed by either board certified gastroenterology physicians or gastroenterology fellows under direct supervision of the board certified gastroenterology physicians. Before enrolling patients into the study all endoscopists involved were in serviced on boston bowel preparation score and scoring cards were made available in each endoscopy suite. BBPS was categorized as described by Lai et al[16]: 0: Unprepared colon segment with mucosa not seen due to solid stool that cannot be cleared; 1: Portion of mucosa of the colon segment seen, but other areas of the colon segment not well seen due to staining, residual stool and/or opaque liquid; 2: Minor amount of residual staining, small fragments of stool and/or opaque liquid, but mucosa of colon segment seen well; and 3: Entire mucosa of colon segment seen well with no residual staining, small fragments of stool or opaque liquid.

For the purpose of study, the colon was divided into three segments- Right (R) (Caecum and Ascending Colon), Transverse (T) (Hepatic Flexure, Transverse Colon and Splenic flexure) and Left (L) (Descending colon, Sigmoid colon and Rectum). A research associate was present during each procedure to record the BBPS reported by the endoscopist in each segment during the procedure (R-0/1/2/3, T-0/1/2/3, L-0/1/2/3). Segmental scores were combined to calculate the composite BBPS. Based on Composite BBPS, subjects were divided into three groups: Group 0- Composite BBPS 0-3, Poor bowel preparation; Group 1- Composite BBPS 4-6, Sub-optimal bowel preparation; and Group 2 - Composite BBPS 7-9, adequate bowel preparation.

As per national guidelines all procedures had a minimal withdrawal time of 6 minutes. Also the site, size and number of polyps were recorded during the procedure. High definition endoscopes were used for the colonoscopy of all enrolled subjects. Pathology report of each polyp was followed to determine segmental and combined AADR. The advanced adenoma bridges benign and malignant states and may be the most valid neoplastic surrogate marker for present and future colorectal cancer risk[17]. Advanced adenoma was defined as 3 or more adenomatous polyps, polyps greater than or equal to 10 mm or histologically having high-grade dysplasia or significant villous components.

To determine the association between AADR and quality of bowel preparation by using segmental and composite BBPS during colonoscopy.

Microsoft Excel software for Windows version 2010 was used. Cross tables with χ2 test were used to compare differences among groups.

The statistical review of the study was done by one of the authors with biomedical research experience. Three hundred and sixty subjects were enrolled in the study. Mean age was 59.2 years, gender distribution was 36.3% males and 63.8% females. Four subjects with incomplete colonoscopy due BBPS of 0 in any segment were excluded. Based on composite BBPS subjects were divided into 3 groups; Group 0: n = 26 (7.3%), Group 1: n = 121 (34%) and Group 3: n = 209 (58.7%). AADR showed a linear trend through Group-0 to 2; with an AADR of 3.8%, 14.8% and 16.7% respectively (Figure 1).

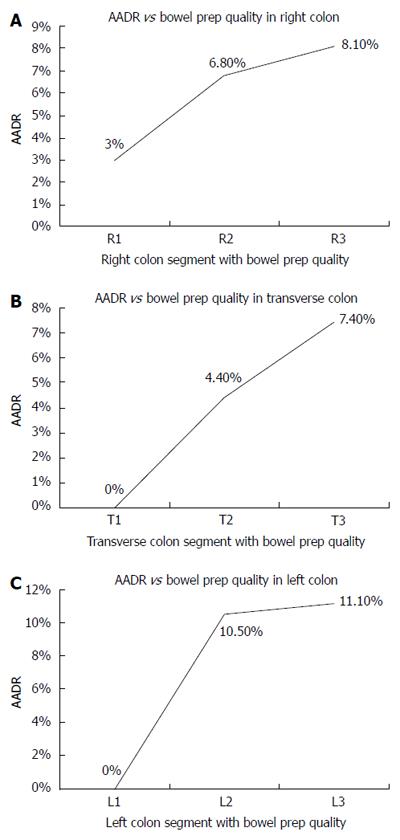

Also seen was a linear increasing trend in segmental AADR with improvement in segmental BBPS (1 to 3); with an AADR of 3%, 6.8% and 8.1% for R-1, R-2, R-3 respectively; 0%, 4.4% and 7.4% for T-1, T-2, T-3 respectively; and 0%, 10% and 11.5% for L-1, L-2, L-3 respectively (Figure 2). There was statistical significant difference between AADR among Group 0 and 2 (3.8% vs 16.7%, P < 0.05), Group 1 and 2 (14.8% vs 16.7%, P < 0.05) and Group 0 and 1 (3.8% vs 14.8%, P < 0.05).

The bowel preparation process before a colonoscopy is directed towards cleaning the colon of the faecal material for better visualisation of colonic mucosa and detection of abnormalities especially polyps present in the colon. Optimal bowel cleansing is pre-requisite for successful colonoscopy, indirectly having impact on both the performance and the effectiveness of the colonoscopy. Colonoscopies with suboptimal bowel preparation have significant adenoma miss rates, suggesting that suboptimal bowel preparation substantially decreases efficiency of colonoscopy as a CRC screening tool[9].The incidence of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy has been reported to be as high as 25%[18]. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy have recommended inclusion of assessment of the quality of bowel preparation in each colonoscopy report[19]. Terms such as excellent, good, fair, and poor were considered appropriate but the committee emphasized that the terms lack standardized definitions[19]. There are several other issues which are unclear such as whether the bowel preparation quality should be documented based on findings upon insertion of the colonoscope, or during withdrawal. Impact of cleansing maneuvers such as washing and suctioning of fluid is not accounted when using this terminology[16]. While former is an assessment of colonic preparation, and the latter is an assessment of the likelihood for missed lesions, a more clinically relevant measure, hence the distinction is important[16]. Furthermore, the variation of bowel preparation in different segments of colon is also not accounted.

Insufficient mucosal visualization during colonoscopy can result in lesions being missed[18,20]. Poor bowel preparation may also result in difficult progression, an increase risk of complications, prolonged procedure duration and an increase in the amount of sedatives and analgetics required[21]. Poor bowel preparation is also a frequent cause for incomplete procedures, resulting in the need for a repeat colonoscopy[21]. It has been suggested that the fact that colonoscopic surveillance does not prevent right-sided cancers is caused by the often worse quality of cleansing of the right side of the colon[22].

Because of these consequences, the quality of bowel preparation needs to be assessed and documented[23]. Suboptimal bowel preparation rates during colonoscopy can be as high as 1/3rd of total colonoscopies[24]. Therefore, knowledge of its risk factors can be very important. A model based on risk factors, such as male gender, inpatient status, and older age, correctly predicted inadequate bowel preparation in only 60% of patients[25].

In an effort to improve colonoscopy outcome, it is essential to report the quality of bowel preparation accurately. Most gastroenterologist continue to use the subjective systems of reporting bowel preparation. Many endoscopist find it difficult to report the bowel preparation quality accurately because of inter-segmental variation. BBPS score allows gastroenterologist to report the quality of bowel preparation for each colon segment in an objective manner. BBPS is sensitive to differences in bowel prep quality within different segments of colon, and therefore helps to identify segment-specific risks for missed pathology. It helps in identifying the potential colon segments which require more detailed examination in repeat colonoscopy. Total and individual segment BBPS scores have demonstrated strong inter- and intra-rater reliability over the full range of possible segment scores[16]. The BBPS is simple to learn and practice and can be seen as a useful tool in standardizing the reporting of bowel prep quality.

Our study showed that segmental AADR correlate with segmental BBPS. Also, AADR shows linear increasing trend with composite BBPS. It is thus valuable to report segmental BBPS in colonoscopy reports in clinical practice. Segmental BBPS can also aid gastroenterologists in deciding the surveillance method for colorectal screening. Patients with suboptimal scores only on the left side can have surveillance using a flexible sigmoidoscopy rather than having a complete colonoscopy. Similarly patients with suboptimal preparation on the right or transverse colon need to have complete colonoscopy. Reporting segmental bowel preparation will also help us identify patient related factors which are associated with suboptimal preparation on one particular segment and hence study interventions that can improve bowel preparation on that segment.

In conclusion, the BBPS is a valid and reliable scoring system for assessing adequacy of bowel preparation during colonoscopy regardless of degree of cleanliness. Documentation of BBPS in all colonoscopy reports will help in: (1) careful examination during repeat colonoscopy of segments which had poor or sub-optimal BBPS on previous colonoscopy; (2) determining appropriate surveillance interval and the procedure for surveillance (flexible sigmoidoscopy vs colonoscopy); (3) determining appropriate interventions to improve bowel preparation for colonoscopy in future; and (4) quality improvement research in colonoscopy when we need to control for bowel preparation quality.

This practice will help in better documentation of the colonoscopy results in relation to the quality of bowel preparation and will be helpful in planning the appropriate course of future intervention for every subject.

The efficiency of colonoscopy as a colorectal cancer screening method depends on the quality of bowel preparation. The interpretation of colonoscopy results depends on looking at the bowel preparation in addition to other findings. Many endoscopist find it difficult to report the bowel preparation quality accurately because of inter-segmental variation. Colonoscopies with suboptimal bowel prep quality are likely to have higher rates of missed lesions and there is a dire need for uniform and more efficient reporting of bowel preparation during colonoscopies.

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy have recommended inclusion of assessment of the quality of bowel preparation in each colonoscopy report. Terms such as excellent, good, fair, and poor were considered appropriate but the committee emphasized that the terms lack standardized definitions. Few bowel preparation scales have been validated till now and their clinical use is still not widely accepted.

Boston bowel preparation score was devised to address the need for reporting segmental bowel preparation scores. A recent study has demonstrated higher polyp detection rate in patients with higher Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) scores than in those with lower BBPS scores during a colonoscopic procedure, consistent with our study results.

Composite and segmental reporting of bowel preparation during colonoscopy will be helpful in following ways: (1) careful examination during repeat colonoscopy of segments which had poor or sub-optimal BBPS on previous colonoscopy; (2) determining appropriate surveillance interval and the procedure for surveillance (flexible sigmoidoscopy vs colonoscopy); (3) determining appropriate interventions to improve bowel preparation for colonoscopy in future; and (4) quality improvement research in colonoscopy when we need to control for bowel preparation quality.

Advanced adenoma was defined as presence of 3 or more adenomatous polyps, polyps greater than or equal to 1 cm or having high-grade dysplasia or significant villous components. Advanced adenoma detection rate - percentage of patients who have one or more advanced adenoma detected. BBPS - Boston Bowel Preparation Score, a validated tool to report quality of bowel preparation

This article focused on an interesting issue: The standardization of preparation colonoscopy evaluation. The results are intuitive, the paper is well-written and easy to understand. The number of patients studied is good.

| 1. | Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 2083] [Article Influence: 173.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Schrag D, Boer R, Winawer SJ, Habbema JD, Zauber AG. How much can current interventions reduce colorectal cancer mortality in the U.S.? Mortality projections for scenarios of risk-factor modification, screening, and treatment. Cancer. 2006;107:1624-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM, Wingo PA, Howe HL, Anderson RN, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3-27. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Based on November 2007 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2008. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/. |

| 5. | Espey DK, Wu XC, Swan J, Wiggins C, Jim MA, Ward E, Wingo PA, Howe HL, Ries LA, Miller BA. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007;110:2119-2152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bond JH. Colon polyps and cancer. Endoscopy. 2003;35:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, Woolf SH, Glick SN, Ganiats TG, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in RCA: 1251] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Winawer SJ. Natural history of colorectal cancer. Am J Med. 1999;106:3S-6S; discussion 50S-51S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1207-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Beck DE. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:10-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | DiPalma JA, Brady CE. Colon cleansing for diagnostic and surgical procedures: polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage solution. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1008-1016. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Tooson JD, Gates LK. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Choosing the best lavage regimen. Postgrad Med. 1996;100:203-204, 207-212, 214. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Calderwood AH, Lai EJ, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. An endoscopist-blinded, randomized, controlled trial of a simple visual aid to improve bowel preparation for screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:307-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tae JW, Lee JC, Hong SJ, Han JP, Lee YH, Chung JH, Yoon HG, Ko BM, Cho JY, Lee JS. Impact of patient education with cartoon visual aids on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:804-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 986] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. The advanced adenoma as the primary target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:1-9, v. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Hollander T, Early DS, Wang JS. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1197-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873-885. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Burke CA, Church JM. Enhancing the quality of colonoscopy: the importance of bowel purgatives. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:565-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy: population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S16-S28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, Pagano N, Spada C, Carrara S, Giordanino C, Rondonotti E, Curcio G, Dulbecco P. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim EJ, Park YI, Kim YS, Park WW, Kwon SO, Park KS, Kwak CH, Kim JN, Moon JS. A Korean experience of the use of Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:219-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chan EC, Grassetto G, Lakatos PL, Paoluzi OA, Rausei S, Xie K S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH