Published online Apr 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3801

Peer-review started: November 17, 2014

First decision: December 26, 2014

Revised: January 14, 2015

Accepted: January 30, 2015

Article in press: January 30, 2015

Published online: April 7, 2015

Processing time: 143 Days and 11.2 Hours

Behçet’s disease (BD) is an idiopathic, chronic, relapsing, multi-systemic vasculitis characterized by recurrent oral and genital aphthous ulcers, ocular disease and skin lesions. Prevalence of BD is highest in countries along the ancient silk road from the Mediterranean basin to East Asia. By comparison, the prevalence in North American and Northern European countries is low. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behçet’s disease are of particular importance as they are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Although ileocecal involvement is most commonly described, BD may involve any segment of the intestinal tract as well as the various organs within the gastrointestinal system. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria - there are no pathognomonic laboratory tests. Methods for monitoring disease activity on therapy are available but imperfect. Evidence-based treatment strategies are lacking. Different classes of medications have been successfully used for the treatment of intestinal BD which include 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody therapy. Like inflammatory bowel disease, surgery is reserved for those who are resistant to medical therapy. A subset of patients have a poor disease course. Accurate methods to detect these patients and the optimal strategy for their treatment are not known at this time.

Core tip: Behçet’s disease is an uncommon subtype of inflammatory bowel disease. It can present with a wide array of clinical manifestations that may mimic other diseases including Crohn’s disease. Establishing the diagnosis remains a challenge and clinicians must be aware of the relevant clinical manifestations and diagnostic considerations. The optimal medical management is limited by the lack of rigorous clinical trial data.

- Citation: Skef W, Hamilton MJ, Arayssi T. Gastrointestinal Behçet's disease: A review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(13): 3801-3812

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i13/3801.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3801

Behçet’s disease (BD) is an inflammatory disorder classically characterized by recurrent oral and genital ulcers, uveitis and characteristic skin lesions. Behçet’s patients can also present with arthritis, gastrointestinal lesions, central nervous symptoms and vascular lesions[1-3]. Table 1 lists the common clinical manifestations of BD. There are no pathognomonic laboratory tests for Behcet’s disease. The most widely accepted criteria were published by the International Study Group (ISG) for Behcet’s Disease in 1990[4]. Diagnosis requires the observation of recurrent oral ulceration (three episodes within any 12 mo period) plus any two of the following: recurrent genital ulceration, eye lesions, skin lesions or a positive pathergy test.

| Skin, Mucocutaneous | Papulopustular lesions (Behçet’s pustulosis), erythema nodosum, superficial thrombophlebitis, minor aphthous ulcers |

| Eyes | Anterior and posterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis |

| Vascular | Deep venous thrombosis, large-vein thrombosis, pulmonary artery aneurysm |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgia, arthritis (monoarticular, oligoarticular) |

| Gastrointestinal | Ileocecal ulcers |

| Genitourinary | Genital ulcers, epididymitis |

| Central nervous system | Meningoencephalitis, parenchymal disease (pyramidal signs, hemiparesis, behavioral changes, sphincter disturbance), intracranial hypertension secondary to dural sinus thrombosis |

Prevalence of BD is highest in countries along the ancient silk road from the Mediterranean Basin to East Asia. Prevalence estimates vary and are reported as 3.8-15.9/100000 in Italy, 7.1/100000 in France, 7.5/100000 in Spain, 7.6/100000 in Egypt, 20-420/100000 in Turkey, 15.2-120/100000 in Israel, 68/100000 in Iran, 14/100000 in China and 7.5-13/100000 in Japan[5-11]. By comparison, prevalence in North American and Northern European countries is rare: varying between 0.27-5.2 per 100000[5]. Mean age of onset is during the 3rd and 4th decades of life[12]. Male-to-female ratio varies regionally - the disease is generally more common amongst men in most Mediterranean, Middle Eastern and Asian countries; conversely, higher female prevalence has been reported in the United States, Northern European and East Asian countries[12,13].

Gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations of Behçet’s disease are of particular importance as they are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. GI manifestations usually occur 4.5-6 years after the onset of oral ulcers[14]. The most common symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and gastrointestinal bleeding[15]. Although ileocecal involvement is most commonly described, BD may involve any segment of the alimentary tract and the various GI organs[14,16]. In general, two forms of intestinal Behçet’s disease exist - neutrophilic phlebitis that leads to mucosal inflammation and ulcer formation and large vessel disease (i.e., mesenteric arteries) that results in intestinal ischemia and infarction[17]. The frequency of GI involvement among patients with BD varies in different countries. Lower frequency has been reported in Turkey (2.8%), India (3.4%) and Saudi Arabia (4%), moderate frequency in China (10%) and Taiwan (32%) and the highest frequency has been reported in the United Kingdom (38%-53%) and Japan (50%-60%)[12,16,18-21]. It is imperative that the clinician caring for patients with BD is aware of the myriad of clinical manifestations, diagnostic methods and treatment strategies available for the gastrointestinal manifestations of BD.

Esophageal involvement in BD is uncommon; incidence rates between 2%-11% have been reported[14]. Esophageal manifestations are associated with involvement of another part of the gastrointestinal tract in more than 50% of cases[16]. Common clinical manifestations include retrosternal chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, melena and hematochezia[22,23]. Endoscopic findings usually consist of a single or multiple ulcers. Ulcers tend to aggregate in the middle or distal third of the esophagus. Serious complications such as stenosis and perforations may occur[24]. “Downhill” esophageal varices have also been reported in patients with obstruction of the caval veins[25,26].

BD may also affect the motility of the esophagus. A study of 25 patients with BD and dyspeptic symptoms demonstrated that 16% had esophageal motor abnormalities. Median lower esophageal pressure (LES) and LES relaxation were significantly lower in the BD group in comparison to age-matched controls[27]. Although routine endoscopy is not recommended in patients with BD[23,28], referral for upper endoscopy and/or esophageal manometry for patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms may be appropriate.

The stomach is thought to be the least involved segment of the gastrointestinal tract. However, consistent with varying phenotypes of disease across different patient populations, one study of 28 patients with BD in Taiwan demonstrated a prevalence of 43% of gastroduodenal involvement amongst those of Chinese descent[29]. Dyspepsia and epigastric abdominal pain were the most common symptoms. Patients either had isolated gastric, isolated duodenal or combined gastroduodenal ulcers.

Rare manifestations in the stomach include dieulafoy’s lesions and gastric non-hodgkins lymphoma[30,31]. Cases of pyloric stenosis due to edematous hypertrophy of the pyloric ring have also been reported[32,33]. Likewise, gastroparesis has also been linked with BD in a case report[34].

The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori does not appear to be increased in patients with BD. This was illustrated in a prospective, single center study of 45 patients with BD and upper gastrointestinal complaints. In comparison to age-matched controls there was no difference in prevalence (73.3% vs 75%, P > 0.05) and eradication rate with two weeks of triple therapy (75% vs 70%, P > 0.05)[35]. Curiously, a study of 13 patients demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in oral and genital ulcerations during the 6 mo follow-up after eradication therapy suggesting a possible etiologic role of Helicobacter pylori[36].

Studies using video capsule endoscopy have demonstrated that BD can involve the entire small bowel[37,38]. Classically intestinal BD manifests as large (> 1 cm), round/oval shaped, deep ulcers in the ileocecal region. This was demonstrated in a landmark Korean study of 94 patients with intestinal BD in which 96% had involvement of the terminal ileum, ileocecal valve or cecum[39]. Localized single (67%) and localized multiple (27%) ulcers were the most common patterns of distribution. Multisegmental and diffuse colonic involvement were rare (6%). Eighty five percent of patients had less than 6 ulcers (67% of single ulcer, 18% of 2-5 ulcers). Ulcers were large with a mean diameter of 2.9 cm (76% of ulcers > 1 cm). Round/oval shape was most common (77%). Deep ulcers were more common (68% vs 38% superficial). Of note, rectal involvement in BD is exceedingly rare and occurs in less than 1% of patients[15].

Rare complications of BD include strictures, abscess formation, fistula and perforation. One study found the rates of perforation, fistula, stricture and abscess to be 12.7%, 7.6%, 7.2% and 3.3% respectively[40]. A series of 22 patients with perforation secondary to intestinal BD demonstrated that all perforations occurred in the terminal ileum, ileocecal region or ascending colon[41]. Risk factors for perforation include age < 25 at diagnosis, history of laparotomy and volcano-shaped ulcers on colonoscopy[42].

In areas where tuberculosis and BD are endemic, it is imperative to make the correct diagnosis as the treatment differs substantially. To our knowledge, there have been no studies conducted comparing intestinal BD to intestinal tuberculosis (ITB). In a study comparing ITB and Crohn’s disease (CD), multivariate analysis demonstrated that blood in stool (OR = 0.1, 95%CI: 0.04-0.5), sigmoid involvement (OR = 0.07, 95%CI: 0.01-0.3) and focally enhanced colitis on histology (OR = 0.1, 95%CI: 0.03-0.5) were more predictive of CD than ITB[43]. Chest radiography may identify pulmonary involvement in 32% of patients with ITB[44]. T-SPOT.TB can be a useful assay but with varying sensitivity and specificity of 83%-100% and 47%-100% respectively[45]. Polymerase chain reaction of endoscopic biopsies has low sensitivity (21.6%) but is highly specific (95%)[46]. A biopsy for specialized culture is definitive but time consuming and has a very low sensitivity[47]. When the diagnosis between the CD and ITB is unclear, expert opinion suggests an empiric 8 wk trial of anti-tuberculous therapy.

The more difficult distinction is between CD and BD. Both diseases typically can present in young patients, are associated with extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs), involve any area of the GI tract and have a waxing and waning course. Table 2 demonstrates the key differences between CD and intestinal BD.

| Crohn’s disease | Intestinal BD | |

| Extra-intestinal manifestations | Iritis, episcleritis more specific | Oral and genital ulcers more common, papulopustular lesions, neurologic and arterial manifestations |

| Perianal disease (fistula, fissures) | Common | Rare |

| Strictures, fistula, abscess | Common, characteristic of disease process | Less common but possible |

| Serologic markers | Anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (Prevalence: 41%-76%) | IgM anti-α-enolase antibody (Prevalence: 67.5%) |

| Endoscopic features | Irregular, longitudinal ulcers with cobblestone appearance, may have aphthous lesions Segmental or diffuse involvement | Round or oval shaped, punched-out lesions with discrete margins, > 1 cm, Focal distribution, < 5 ulcers. No aphthous lesions |

| Pathognomonic lesions on histopathology | Non-caseating epithelioid granuloma | Non-specific neutrophilic or lymphocytic phlebitis with or without aortitis |

CD and BD share many EIMs in common including oral ulcers, uveitis, arthritis and erythema nodosum - although-oral ulcers and uveitis are more common in BD. Genital ulcers, a hallmark of BD, are rare in CD. Amongst eye findings, episcleritis and iritis are more specific for CD whereas retinal vasculitis is more commonly associated with BD[48]. Both diseases have an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis - however, CD is not associated with other vascular manifestations such as varices, Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BCS) or arterial vasculitis. Neurologic disease, an important complication in BD, is typically not associated with CD.

Intestinal complications such as strictures, fistula and abscess occur in both diseases but are less common in BD. Jung et al[40] found that fistula (CD: 27.4% vs BD: 7.6%, P≤ 0.001), strictures (CD: 38.3% vs BD: 7.2%, P≤ 0.001) and abscess formation (CD: 19.6% vs BD: 3.3%, P≤ 0.001) were more common in CD. Perforation was more common in BD although not statistically significant (CD: 8.7% vs BD: 12.7%, P = 0.114). Perianal fistula was a rare complication in BD (CD: 39.2% vs BD: 2.5%, P≤ 0.001).

Serologic testing appears to be less reliable in differentiating between CD and BD. Anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody, a specific marker for CD, is positive in 41%-76% of patients with CD[49] and 0%-44.3% of patients with BD[50,51] making it unhelpful in differentiating between the two diseases. The data for IgM anti-Alpha-Enolase Antibody is quite similar. The antibody is reported to be present in 67.5% of patients with intestinal BD[52] and 50% of patients with CD[53].

Colonoscopic findings can help differentiate accurately between the two diseases. A study of 235 patients with CD and intestinal BD found that round ulcer, focal single/focal multiple distribution of ulceration, less than 6 ulcers, absence of cobblestone appearance or aphthous lesions were most predictive of BD on colonoscopy in multivariate analysis[54]. Although non-epithelioid granuloma can be found in CD in 30% of patients[54], there are no other pathologic features that may help distinguish between CD and BD on intestinal mucosal biopsies.

Pancreatic involvement in BD is exceptionally rare. Very few case reports of acute pancreatitis have been attributed to BD[55,56]. Chronic pancreatitis was also reported in a patient with BD - however he also had a history of heavy alcohol intake[57]. It is possible that pancreatic involvement is underreported or underdiagnosed - an autopsy series of 170 cases from Japan suggested 2.9% involvement of the pancreas[58]. Vasculitis is likely the underlying pathological process leading to pancreatic inflammation - this theory is further supported by other vasculitic syndromes such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis which has also been associated with pancreatitis[59].

BCS is the most common manifestation of the liver in patients with BD. BCS may be a serious complication and associated with a high mortality rate. Venous thrombosis secondary to endothelial dysfunction from vasculitis has been proposed as a possible mechanism[60]. Studies have reported prevalence rates between 1.3%-3.2%[61-63]. Men are more likely to develop BCS than females. Presenting signs and symptoms include right upper quadrant abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly and ascites[64]. Patients can present with acute, subacute or chronic BCS. Acute BCS appears to carry a very poor prognosis[65]. Thrombosis of the hepatic veins (HV), inferior vena cava (IVC) and portal vein (PV) may occur. In a Turkish series of 14 patients with BCS secondary to BD, 2 had isolated HV involvement, 8 had HV and IVC involvement and 4 had HV, IVC and PV involvement. Six out of 8 with HV and IVC involvement and 4/4 of those with PV, HV and IVC involvement died with mean survival of 10.4 mo[62]. It appears the extent of IVC obstruction appears to be the major determinant of survival in BD patients with BCS. Notable complications from BCS include hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, lower extremity edema, esophageal varices and liver failure.

Given the relatively high prevalence and significant mortality rate of BCS in BD patients, some authors suggest that all patients with BD should be screened for BCS with duplex ultrasonography[61]. Other uncommon manifestations of BD include aseptic abscess formation in the liver, chronic hepatitis and sclerosing cholangitis[66-68].

BD is a unique form of vasculitis because it can involve arteries and veins of all sizes[69]. One study of 38 BD patients with vascular involvement found that venous involvement was by far the most prevalent (88%)[70]. Incidence of vascular involvement varies between 7%-29%[71]. Males are more commonly affected[72]. Arterial manifestations include formation of aneurysms and luminal thrombi[64]. Important sites of arterial involvement include the arteries of the upper and lower extremities (radial, femoral, popliteal)[73], pulmonary artery[74] and thoracoabdominal aorta[75]. Other sites of involvement include the subclavian[76], iliac[77], carotid[78,79], renal[80] and coronary arteries[81].

Arterial involvement of the intra-abdominal organs is rare. When it occurs, patients may present with fever, abdominal pain or pulsatile mass. Complications can include intestinal infarction and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Very few cases of visceral aortic aneurysm exist in the literature - involvement of the celiac trunk[82], superior mesenteric[83], hepatic[84], splenic[85], inferior mesenteric[86] and ileocolic artery[87] have been described.

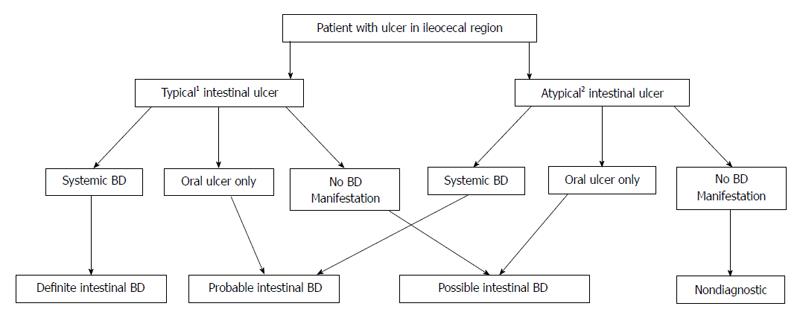

Establishing the diagnosis of intestinal BD remains a challenge. Previously, the diagnosis was based primarily on the combination of clinical criteria for systemic BD with the presence of intestinal ulcer formation[88]. However, the dilemma is that not all patients with “typical” intestinal ulcers satisfy ISG criteria for systemic BD at the time of endoscopy - this often leads to delayed or misdiagnosis. As a result, Cheon et al[88] proposed four separate categories of classification using the modified Delphi process: definite, probable, suspected and non-diagnostic for intestinal BD (Figure 1). In their study, 145 (51.8%) of 280 patients were confirmed to have intestinal BD. Using this algorithm, the first 3 categories provide for a pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of 98.6%, 83%, 86.1% and 98.2%, respectively.

A clinical scoring system called the Disease Activity Index for Intestinal BD (DAIBD) exists. Prior to its development in 2011 by Cheon et al[89], other IBD indices such as the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index or Harvey-Bradshaw Index were frequently used. The DAIBD provides a score between 0 and 325 based on an 8-point index. It classifies disease activity as quiescent (≤ 19), mild (20-39), moderate (40-74) and severe (≥ 75). Laboratory and endoscopic data are not part of the scoring system making it ideal for use in the outpatient setting (see Table 3). A later study demonstrated that the correlation between DAIBD and endoscopic severity was weak (r = 0.43)[90]. It is still unclear whether endoscopic severity is superior to clinical severity in predicting prognosis.

| Item | Score |

| General well-being in the preceding week | |

| Well | 0 |

| Fair | 10 |

| Poor | 20 |

| Very poor | 30 |

| Terrible | 40 |

| Fever | |

| < 38 °C | 0 |

| ≥ 38 °C | 10 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 5 points for each manifestation1 |

| Abdominal pain in the preceding week | |

| None | 0 |

| Mild | 20 |

| Moderate | 40 |

| Severe | 80 |

| Abdominal mass | |

| None | 0 |

| Palpable mass | 10 |

| Abdominal tenderness | |

| None | 0 |

| Mildly tender | 10 |

| Moderately or severely tender | 20 |

| Intestinal complications | 10 points for each complication2 |

| Number of liquid stools in the preceding week | |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1-7 | 10 |

| 8-21 | 20 |

| 22-35 | 30 |

| ≥ 36 | 40 |

| Total score | |

| Severity of disease | |

| Quiescent Intestinal BD | ≤ 19 |

| Mild intestinal BD | 20-39 |

| Moderate intestinal BD | 40-74 |

| Severe intestinal BD | ≥ 75 |

Serum biologic markers are a helpful adjunct in monitoring disease activity in intestinal BD. Soluble triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells-1 demonstrates the highest degree of correlation with disease activity of intestinal BD[91]. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate have also been demonstrated to correlate with disease activity. Unexpectedly, serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are not a good biologic marker of intestinal BD activity. Stool markers of inflammation that have been shown to correlate with disease activity in patients with CD and UC including fecal calprotectin have not been studied to date in patients with BD.

Management of Behçet’s syndrome is challenging because of a general lack of high quality evidence[92]. Although some controlled data exists for management of arthritis, eye involvement and mucocutaneous disease, there is a considerable lack of evidence addressing treatment strategies for neurologic and vascular manifestations. Similarly, there are no internationally accepted, standardized treatment strategies for gastrointestinal BD. In order to standardize treatment, the Japanese Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Group proposed a set of consensus statements in 2007 - they were updated again in 2014 to address growing low-level evidence supporting the use of anti-TNF-α mAb therapy[93,94]. Generally, with some exceptions, the same classes of medications that have been used for the treatment of systemic BD have also been used to treat intestinal BD and include colchicine, 5-ASA/sulfasalazine, corticosteroids (CS), immunomodulators, immunosuppressants, IFNα and anti-TNF-α mAb therapy. Table 4 summarizes the highest level of evidence for each modality of therapy.

| Therapy | Level(s) of published evidence |

| 5-ASA/sulfasalazine | Retrospective cohort study[95] |

| Corticosteroids | Expert opinion, European League Against Rheumatism Recommendations[114] |

| Thalidomide | Case reports[131-133] |

| Azathioprine, 6-MP | Retrospective cohort studies[97,123] |

| Mycophenolate | Case report[134] |

| Methotrexate | Case series[135] |

| Tacrolimus | Case report[136] |

| Infliximab | Single arm clinical trial[102], Retrospective cohort study[104] |

| Case series[101] | |

| Adalimumab | Prospective, non-placebo controlled clinical trial[110] |

| Etanercept | Case report[112] |

Similar to IBD, sulfasalazine (3-4 g/d) and 5-ASA (2.25-3 g/d) have been the traditional mainstay of therapy. In a retrospective, single center Korean study of 143 patients with intestinal BD treated with 5-ASA/sulfasalazine monotherapy, 46 (32.2%) patients had a clinical relapse (defined as DAIBD ≥ 20)[95]. Younger age at time of diagnosis (< 35 years), elevated CRP (≥ 1.5 mg/dL) and increased disease activity (DAIBD ≥ 60) were associated with higher relapse rates. The authors concluded that 5-ASA/sulfasalazine should be reserved for mild-to-moderate intestinal BD.

CS are usually reserved for moderate to severe disease in order to induce remission[93,94,96]. Doses of 20-100 mg prednisolone have been used depending on the severity of the disease[1]. Expert opinion recommends a weight-based approach of 0.5-1 mg/kg per day of prednisolone for 1-2 wk followed by a taper of 5 mg weekly until discontinuation[93,94]. Hospitalized patients with severe disease may require intravenous methylprednisolone therapy[15]. Intravenous pulse therapy of 1 gram/d for 3 d followed by oral prednisolone taper has been advocated[2]. At 1 mo, almost 1/2 of patients achieve complete remission, 43% attain partial remission and 11% will demonstrate no response (i.e., steroid resistance). Patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-resistant can be difficult to manage and often times require additional therapy (immunomodulators, anti-TNF-α mAb) or surgery. Maintenance therapy with CS is not appropriate and long term steroid use should be avoided given the significant systemic side effects.

Thiopurines are indicated in patients with steroid-dependent disease, enterocutaneous fistulae and maintenance of postoperative remission. Expert opinion advocates starting azathioprine at doses of 25-50 mg/d with gradual titration every 2-4 wk to 2.0-2.5 mg/kg[94]. The starting dose of 6-MP is 0.5 mg/kg and similarly is escalated every 2-4 wk to a goal dose of 1.0-1.5 mg/kg[97]. In a retrospective analysis of 272 patients with intestinal BD, 67 patients were started on thiopurines (66 on azathioprine, 1 on 6-mercaptopurine) during hospitalization for the above three indications. Of the 39 patients who were maintained on thiopurines, the relapse rates were 5.8%, 43.7% and 51.7% at one, three and five years respectively[97]. Younger age at the time of diagnosis of intestinal BD (< 25 years) and a lower hemoglobin level (< 11 g/dL) were independent risk factors for relapse on thiopurine maintenance therapy.

Anti-TNF-α mAb therapy alone or in combination with immunomodulatory therapy is also a modality of treatment for patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-resistant intestinal BD. Sfikakis et al[98] recommend the introduction of Anti-TNF-α mAb therapy only in patients who have failed two immunosuppressive agents and require prednisolone at a dosage > 7.5 mg/d. Infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) are the two best studied biologic agents. The first published case reports of IFX success were in 2001; clinical response to IFX was demonstrated in 3 patients with steroid dependent BD in two separate case reports[99,100]. A larger case series of 6 patients was also promising. Four out of 6 patients who received induction and maintenance therapy (5 mg/kg) at 0, 2 and 6 wk and every 2 mo onwards maintained remission. The other two patients had persistent ileal ulceration and required surgery - however, 1 of those two patients remained in remission on IFX after surgery[101]. Similar results were replicated in several other studies suggesting that IFX has good efficacy and tolerability for refractory intestinal BD[102,103]. A Korean multi-center retrospective study of 28 patients treated with IFX demonstrated that older age (> 40 years), female sex, longer duration of disease (> 5 years), concomitant immunomodulator use and achievement of remission within 4 wk were predictive of sustained response[104].

Remission has also been successfully demonstrated with ADA in several case reports[105-108]. ADA provides a subcutaneous option which is sometimes preferred by some patients[109]. Recently, the efficacy and safety of ADA was investigated in a prospective, non-placebo controlled, multi-center trial in Japan of 20 patients with refractory intestinal BD disease[110]. A novel composite index which combined patient reported GI symptoms in the preceding 2 wk and change in ulcer size based on endoscopic assessment was used to evaluate efficacy. Nine (45%) and 12 patients (60%) demonstrated improvement at 24 and 52 wk respectively. Four patients (20%) were able to achieve complete early and late remission at weeks 24 and 52 respectively. Furthermore, 8 of 13 patients on steroids at baseline were able to completely discontinue them during the study.

Etanercept (ETN) in a double-blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial of 40 men in Turkey demonstrated efficacy against mucocutaneous involvement - specifically oral ulcers and nodular lesions[111]. We are only aware of one case of successful treatment in a pediatric patient with refractory intestinal BD[112] - it is worth noting she was simultaneously treated with tacrolimus, prednisolone and mizoribine. Despite its use for other manifestations of BD, ETN currently has no role in the management of refractory intestinal BD and thus is not addressed in the most recent guidelines[94]. Interestingly, ETN was not shown to be effective for patients with moderate to severe CD[113].

Despite promising low-level evidence documenting success of anti-TNF-α mAb therapies, a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial is necessary to validate their use. The feasibility of conducting large placebo-controlled trials is uncertain given the difficulty recruiting patients with refractory intestinal BD.

Regarding BCS, treatment options include medical therapy, interventional procedures and surgical management. Ascites can be managed with salt restriction and diuretic therapy. Endoscopy may be clinically indicated to assess and treat possible varices. Although there is limited data to guide management of major venous involvement, monthly cyclophosphamide and CS form the cornerstone of therapy for BCS[114]. Anticoagulation is controversial and is not recommended in the most recent European League Against Rheumatism guidelines[114]. Nevertheless, long term anticoagulation with warfarin is still commonplace and advocated by some authors[61,63]. IFX has been attempted but was unsuccessful in 2 patients with advanced disease refractory to monthly cyclophosphamide and CS. A third patient appeared to have regression of disease in IVC - however the development of cranial sinus thrombosis prompted the investigators to discontinue IFX[115]. It remains unclear whether anti-TNFα mAb therapy or anticoagulation has a role in BCS in BD.

Although immunosuppressive treatments are generally indicated in patients with arterial aneurysms, definitive therapy with open or endovascular repair is required because of a high risk of rupture. Treatment with prednisolone 5-60 mg/d combined with azathioprine (50-100 mg/d) and/or colchicine (1.2 mg/d) has been advocated by some experts[116].

As in patients with IBD, surgical therapy is reserved for those who are refractory to medical therapy or presenting with severe gastrointestinal bleed. Other indications for surgery include perforation, fistula formation, intestinal obstruction and abdominal mass[117]. It is interesting to note that ileal disease and ocular lesions are associated with increased risk of surgical resection[118].

There is controversy over the type of surgical procedure and length of bowel to remove. Traditionally, right hemicolectomy, ileocolectomy and partial resection of the small bowel are most commonly performed. Chou et al[41] recommended up to 80 cm of ileal resection from the ileocecal valve at the time of right hemicolectomy More recently, authors suggest a conservative approach with removal of only the grossly involved bowel as there appears to be no relation between length of resection and rates of recurrence or reoperation[117].

For select BD patients who undergo surgery, creation of a stoma may be preferable over primary anastomosis given a high rate of intestinal leakage, perforation and fistulization at the anastomosis site[14,42]. Reoperation in those who undergo surgery is high - 30%-44% and often occurs at or near the anastomosis site (similar to CD)[117-119]. Independent predictors of reoperation include history of postoperative steroid therapy, CRP levels greater than 4.4 or endoscopic evidence of “volcano-type” deep ulcers.

If medical therapy fails in BCS, percutaneous angioplasty provides an attractive option if the segment of thrombosis in the HV or IVC is focal[120]. Alternatively, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt may be another appropriate option. It is unclear whether surgical portosystemic shunting affects survival. Orthotopic liver transplantation has been performed as a life-saving procedure in patients with BCS.

Arterial aneurysms in BD are generally treated surgically because of a high risk of rupture. Although open surgical repair (synthetic vs autologous vein graft) were previously the preferred method, an endovascular approach has emerged as a more durable alternative[64]. A Korean study of 16 BD patients who underwent endovascular repair demonstrated a patency rate of 89% at 2 years[121]. A more recent study confirmed that endovascular therapy is safe and has long term durability[116]. Concomitant treatment with immunosuppressive medications is necessary to control vessel wall inflammation.

Unlike CD whereby many patients may experience a disease flare-up and subsequent corticosteroid and/or immunosuppressive treatment at least once in their lifetime, intestinal BD generally follows a distinguishable mild or severe clinical course. This was illustrated in a 5 year retrospective study of 130 patients with intestinal BD which demonstrated that a large proportion of patients (77.1%) experienced a mild clinical course; on the other hand, 28.5% had a more severe clinical course with multiple relapses and/or chronic symptoms[122]. Other studies cite a similar recurrence rate of 24.9%-28% and 43%-49% at 2 and 5 years respectively[123-125].

Although the prognosis of intestinal BD was previously believed to be worse than CD, a retrospective cohort study of 332 CD and 276 Intestinal BD demonstrated no difference in cumulative probability of disease related surgery (P = 0.287) or hospital admission (P = 0.259) over a mean follow-up period of almost 7 years[40]. Furthermore, there was no observed difference in postoperative clinical recurrence (P = 0.724) or reoperation rates (P = 0.770).

Nonetheless, despite no significant long term difference in outcomes in comparison with CD, surgery rates still remain high. Cumulative rates of surgical interventions are 20% at 1 year, 27%-33% at 5 years and 31%-46% at 10 years after diagnosis[126-128]. Many clinical variables have been investigated as predictors of outcomes during medical and surgical therapy: young age, high disease activity at time of diagnosis, “volcano-type” ulcers on endoscopy or colonoscopy, elevated CRP and history of laparotomy confer the poorest prognosis[126].

Death from intestinal BD is uncommon. Disease-specific mortality in BD is mainly due to major vessel disease (arterial aneurysm, BCS) or neurologic involvement[129].

Behçet’s disease can present with a wide array of gastrointestinal manifestations. Although ileocecal involvement is classically associated with BD, any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus can be involved and there may be appreciable morbidity and mortality associated with gastrointestinal BD. Diagnosis remains a challenge with no universally accepted criteria. Management can be confusing and there are no unanimously accepted treatment algorithms. The goal of treatment is to keep patients in clinical remission, reduce relapses and prevent surgical intervention. Although endoscopic remission is a treatment goal in IBD, there is currently insufficient evidence in the literature to recommend mucosal healing as a treatment goal in BD[94]. Treatment requires cooperation across multiple specialties including the primary care physician, rheumatologist, gastroenterologist and possibly interventional radiologist and/or surgeon. Anti-TNF-α mAb therapy appears to be promising for more severe and/or refractory intestinal disease - more clinical trials are necessary to support their use. A certain subset of patients have a poor disease course and better methods to identify them early in the disease course will be an important area of study. It is unclear at this time which populations of BD patients may benefit from early aggressive therapy and whether this intervention will have an impact on the progression of disease.

| 1. | Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1251] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Saleh Z, Arayssi T. Update on the therapy of Behçet disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5:112-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Hamdan A, Mansour W, Uthman I, Masri AF, Nasr F, Arayssi T. Behçet’s disease in Lebanon: clinical profile, severity and two-decade comparison. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:364-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mahr A, Maldini C. [Epidemiology of Behçet’s disease]. Rev Med Interne. 2014;35:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Cakir N, Dervis E, Benian O, Pamuk ON, Sonmezates N, Rahimoglu R, Tuna S, Cetin T, Sarikaya Y. Prevalence of Behçet’s disease in rural western Turkey: a preliminary report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:S53-S55. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Azizlerli G, Köse AA, Sarica R, Gül A, Tutkun IT, Kulaç M, Tunç R, Urgancioğlu M, Dişçi R. Prevalence of Behçet’s disease in Istanbul, Turkey. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:803-806. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Krause I, Yankevich A, Fraser A, Rosner I, Mader R, Zisman D, Boulman N, Rozenbaum M, Weinberger A. Prevalence and clinical aspects of Behcet’s disease in the north of Israel. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Jaber L, Milo G, Halpern GJ, Krause I, Weinberger A. Prevalence of Behçet’s disease in an Arab community in Israel. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:365-366. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Davatchi F, Jamshidi AR, Banihashemi AT, Gholami J, Forouzanfar MH, Akhlaghi M, Barghamdi M, Noorolahzadeh E, Khabazi AR, Salesi M. WHO-ILAR COPCORD Study (Stage 1, Urban Study) in Iran. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1384. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Zhang Z, He F, Shi Y. Behcet’s disease seen in China: analysis of 334 cases. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:645-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, Shams H, Nadji A, Akhlaghi M, Faezi T, Ghodsi Z, Faridar A, Ashofteh F. Behcet’s disease: from East to West. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:823-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Calamia KT, Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Behçet’s disease in the US: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:600-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Bayraktar Y, Ozaslan E, Van Thiel DH. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behcet’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:144-154. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Grigg EL, Kane S, Katz S. Mimicry and deception in inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal behçet disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:103-112. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behçet’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Vaiopoulos AG, Sfikakis PP, Kanakis MA, Vaiopoulos G, Kaklamanis PG. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behçet’s disease: advances in evaluation and management. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:S140-S148. [PubMed] |

| 18. | al-Dalaan AN, al Balaa SR, el Ramahi K, al-Kawi Z, Bohlega S, Bahabri S, al Janadi MA. Behçet’s disease in Saudi Arabia. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:658-661. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Chen YC, Chang HW. Clinical characteristics of Behçet’s disease in southern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2001;34:207-210. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wang LY, Zhao DB, Gu J, Dai SM. Clinical characteristics of Behçet’s disease in China. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1191-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Singal A, Chhabra N, Pandhi D, Rohatgi J. Behçet’s disease in India: a dermatological perspective. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Yi SW, Cheon JH, Kim JH, Lee SK, Kim TI, Lee YC, Kim WH. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of esophageal involvement in patients with Behçet’s disease: a single center experience in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:52-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Houman MH, Ben Ghorbel I, Lamloum M, Khanfir M, Braham A, Haouet S, Sayem N, Lassoued H, Miled M. Esophageal involvement in Behcet’s disease. Yonsei Med J. 2002;43:457-460. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Morimoto Y, Tanaka Y, Itoh T, Yamamoto S, Kurihara Y, Nishikawa K. Esophagobronchial fistula in a patient with Behçet’s disease: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tavakkoli H, Asadi M, Haghighi M, Esmaeili A. Therapeutic approach to “downhill” esophageal varices bleeding due to superior vena cava syndrome in Behcet’s disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:43. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Orikasa H, Ejiri Y, Suzuki S, Ishikawa H, Miyata M, Obara K, Nishimaki T, Kasukawa R. A case of Behçet’s disease with occlusion of both caval veins and “downhill” esophageal varices. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:506-510. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Bektas M, Altan M, Alkan M, Ormeci N, Soykan I. Manometric evaluation of the esophagus in patients with Behçet’s disease. Digestion. 2007;76:192-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Bottomley WW, Dakkak M, Walton S, Bennett JR. Esophageal involvement in Behçet’s disease. Is endoscopy necessary? Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:594-597. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Ning-Sheng L, Ruay-Sheng L, Kuo-Chih T. High frequency of unusual gastric/duodenal ulcers in patients with Behçet’s disease in Taiwan: a possible correlation of MHC molecules with the development of gastric/duodenal ulcers. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Abe T, Yachi A, Yabana T, Ishii Y, Tosaka M, Yoshida Y, Yonezawa K, Ono A, Ikeda N, Matsuya M. Gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma associated with Behçet’s disease. Intern Med. 1993;32:663-667. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Arendt T, Kloehn S, Bastian A, Bewig B, Lins M, Mönig H, Fölsch UR. A case of Behçet‘s syndrome presenting with Dieulafoy‘s ulcer. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:935-938. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Ozenç A, Bayraktar Y, Baykal A. Pyloric stenosis with esophageal involvement in Behçet’s syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:727-728. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Satake K, Yada K, Ikehara T, Umeyama K, Inoue T. Pyloric stenosis: an unusual complication of Behçet’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:816-818. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Bertken R. Infliximab treatment of Behcet disease associated with severe gastroparesis. Washington, DC, USA: The National Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology 2001; . |

| 35. | Ersoy O, Ersoy R, Yayar O, Demirci H, Tatlican S. H pylori infection in patients with Behcet’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2983-2985. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Avci O, Ellidokuz E, Simşek I, Büyükgebiz B, Güneş AT. Helicobacter pylori and Behçet’s disease. Dermatology. 1999;199:140-143. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Neves FS, Fylyk SN, Lage LV, Ishioka S, Goldenstein-Schainberg C, Sakai P, Gonçalves CR. Behçet’s disease: clinical value of the video capsule endoscopy for small intestine examination. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:601-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hamdulay SS, Cheent K, Ghosh C, Stocks J, Ghosh S, Haskard DO. Wireless capsule endoscopy in the investigation of intestinal Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1231-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Lee CR, Kim WH, Cho YS, Kim MH, Kim JH, Park IS, Bang D. Colonoscopic findings in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:243-249. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Long-term clinical outcomes of Crohn’s disease and intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 41. | Chou SJ, Chen VT, Jan HC, Lou MA, Liu YM. Intestinal perforations in Behçet’s disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Moon CM, Cheon JH, Shin JK, Jeon SM, Bok HJ, Lee JH, Park JJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim NK. Prediction of free bowel perforation in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease using clinical and colonoscopic findings. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2904-2911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Makharia GK, Srivastava S, Das P, Goswami P, Singh U, Tripathi M, Deo V, Aggarwal A, Tiwari RP, Sreenivas V. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiations between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:642-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Ibrahim M, Osoba AO. Abdominal tuberculosis. On-going challenge to gastroenterologists. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:274-280. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Lei Y, Yi FM, Zhao J, Luckheeram RV, Huang S, Chen M, Huang MF, Li J, Zhou R, Yang GF. Utility of in vitro interferon-γ release assay in differential diagnosis between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND, Amarapurkar AD, Agal S, Baigal R, Gupte P. Tissue polymerase chain reaction in diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:863-867. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Ng SC, Chan FK. Infections and inflammatory bowel disease: challenges in Asia. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:567-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Yazısız V. Similarities and differences between Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:228-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 49. | Papp M, Norman GL, Altorjay I, Lakatos PL. Utility of serological markers in inflammatory bowel diseases: gadget or magic? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2028-2036. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Filik L, Biyikoglu I. Differentiation of Behcet’s disease from inflammatory bowel diseases: anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody and anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7271. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Choi CH, Kim TI, Kim BC, Shin SJ, Lee SK, Kim WH, Kim HS. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody in intestinal Behçet’s disease patients: relation to clinical course. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1849-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Shin SJ, Kim BC, Kim TI, Lee SK, Lee KH, Kim WH. Anti-alpha-enolase antibody as a serologic marker and its correlation with disease severity in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:812-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 53. | Vermeulen N, Arijs I, Joossens S, Vermeire S, Clerens S, Van den Bergh K, Michiels G, Arckens L, Schuit F, Van Lommel L. Anti-alpha-enolase antibodies in patients with inflammatory Bowel disease. Clin Chem. 2008;54:534-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 54. | Lee SK, Kim BK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Differential diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease by colonoscopic findings. Endoscopy. 2009;41:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 55. | Le Thi Huong D, Wechsler B, Dell’Isola B, Lautier-Frau M, Palazzo L, Bletry O, Piette JC, Godeau P. Acute pancreatitis in Behçet’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1452-1453. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Backmund M, Schomerus P. Acute pancreatitis and pericardial effusion in Behçet’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:286. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Alkim H, Gürkaynak G, Sezgin O, Oğuz D, Saritaş U, Sahin B. Chronic pancreatitis and aortic pseudoaneurysm in Behçet’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:591-593. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Lakhanpal S, Tani K, Lie JT, Katoh K, Ishigatsubo Y, Ohokubo T. Pathologic features of Behçet’s syndrome: a review of Japanese autopsy registry data. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:790-795. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Chawla S, Atten MJ, Attar BM. Acute pancreatitis as a rare initial manifestation of Wegener’s granulomatosis. A case based review of literature. JOP. 2011;12:167-169. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Kuniyoshi Y, Koja K, Miyagi K, Uezu T, Yamashiro S, Arakaki K, Mabuni K, Senaha S. Surgical treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome induced by Behcet’s disease. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;8:374-380. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Ben Ghorbel I, Ennaifer R, Lamloum M, Khanfir M, Miled M, Houman MH. Budd-Chiari syndrome associated with Behçet’s disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:316-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 62. | Bayraktar Y, Balkanci F, Bayraktar M, Calguneri M. Budd-Chiari syndrome: a common complication of Behçet’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:858-862. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Korkmaz C, Kasifoglu T, Kebapçi M. Budd-Chiari syndrome in the course of Behcet’s disease: clinical and laboratory analysis of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:245-248. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Calamia KT, Schirmer M, Melikoglu M. Major vessel involvement in Behçet’s disease: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 65. | Orloff LA, Orloff MJ. Budd-Chiari syndrome caused by Behçet’s disease: treatment by side-to-side portacaval shunt. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:396-407. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Manna R, Ghirlanda G, Bochicchio GB, Papa G, Annese V, Greco AV, Taranto CA, Magaro M. Chronic active hepatitis and Behçet’s syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 1985;4:93-96. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Maeshima K, Ishii K, Inoue M, Himeno K, Seike M. Behçet’s disease complicated by multiple aseptic abscesses of the liver and spleen. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3165-3168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 68. | Hisaoka M, Haratake J, Nakamura T. Small bile duct abnormalities and chronic intrahepatic cholestasis in Behçet’s syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:267-270. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Melikoglu M, Kural-Seyahi E, Tascilar K, Yazici H. The unique features of vasculitis in Behçet’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008;35:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 70. | Koç Y, Güllü I, Akpek G, Akpolat T, Kansu E, Kiraz S, Batman F, Kansu T, Balkanci F, Akkaya S. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:402-410. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Lie JT. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease: arterial and venous and vessels of all sizes. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:341-343. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Sarica-Kucukoglu R, Akdag-Kose A, KayabalI M, Yazganoglu KD, Disci R, Erzengin D, Azizlerli G. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease: a retrospective analysis of 2319 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:919-921. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Koksoy C, Gyedu A, Alacayir I, Bengisun U, Uncu H, Anadol E. Surgical treatment of peripheral aneurysms in patients with Behcet’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:525-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 74. | Uzun O, Akpolat T, Erkan L. Pulmonary vasculitis in behcet disease: a cumulative analysis. Chest. 2005;127:2243-2253. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Umehara N, Saito S, Ishii H, Aomi S, Kurosawa H. Rupture of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm associated with Behcet’s disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1394-1396. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Yildirim A, Isik A, Koca S. Subclavian artery pseudoaneurysm in Behcet’s disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1151-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Memetoglu ME, Kalkan A. Behcet’s disease with aneurysm of internal iliac artery and percutaneous treatment. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:372-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 78. | Albeyoglu S, Cinar B, Eren T, Filizcan U, Bayserke O, Aslan C. Extracranial carotid artery aneurysm due to Behcet’s disease. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2010;18:574-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 79. | Agrawal S, Jagadeesh R, Aggarwal A, Phadke RV, Misra R. Aneurysm of the internal carotid artery in a female patient of Behcet’s disease: a rare presentation. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:994-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Planer D, Verstandig A, Chajek-Shaul T. Transcatheter embolization of renal artery aneurysm in Behçet’s disease. Vasc Med. 2001;6:109-112. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Arishiro K, Nariyama J, Hoshiga M, Nakagawa A, Okabe T, Nakakoji T, Negoro N, Ishihara T, Hanafusa T. Vascular Behçet’s disease with coronary artery aneurysm. Intern Med. 2006;45:903-907. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Basaranoglu G, Basaranoglu M. Behcet’s disease complicated with celiac trunk aneurysm. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:174-175. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Chubachi A, Saitoh K, Imai H, Miura AB, Kotanagi H, Abe T, Matsumoto T. Case report: intestinal infarction after an aneurysmal occlusion of superior mesenteric artery in a patient with Behçet’s disease. Am J Med Sci. 1993;306:376-378. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Oto A, Cekirge S, Gülsün M, Balkanci F, Besim A. Hepatic artery aneurysm in a patient with Behçetś disease and segmental pancreatitis developing after its embolization. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1294-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 85. | Dolar E, Uslusoy H, Kiyici M, Gurel S, Nak SG, Gulten M, Zorluoglu A, Saricaoglu H, Memik F. Rupture of the splenic arterial aneurysm due to Behcet’s disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:1327-1328. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Morimoto N, Okita Y, Tsuji Y, Inoue N, Yokoyama M. Inferior mesenteric artery aneurysm in Behçet syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:1434-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 87. | Hong YK, Yoo WH. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to the rupture of arterial aneurysm in Behçet’s disease: case report and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:1151-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 88. | Cheon JH, Kim ES, Shin SJ, Kim TI, Lee KM, Kim SW, Kim JS, Kim YS, Choi CH, Ye BD. Development and validation of novel diagnostic criteria for intestinal Behçet’s disease in Korean patients with ileocolonic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2492-2499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 89. | Cheon JH, Han DS, Park JY, Ye BD, Jung SA, Park YS, Kim YS, Kim JS, Nam CM, Kim YN. Development, validation, and responsiveness of a novel disease activity index for intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:605-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 90. | Lee HJ, Kim YN, Jang HW, Jeon HH, Jung ES, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Nam CM. Correlations between endoscopic and clinical disease activity indices in intestinal Behcet’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5771-5778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 91. | Jung YS, Kim SW, Yoon JY, Lee JH, Jeon SM, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Expression of a soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) correlates with clinical disease activity in intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2130-2137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, Houman MH, Kötter I, Olivieri I, Salvarani C. Management of Behçet disease: a systematic literature review for the European League Against Rheumatism evidence-based recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1528-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 93. | Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, Iwao Y, Fukushima T, Hiwatashi N, Igarashi M, Iizuka BE, Matsuda T, Matsui T. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:737-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 94. | Hisamatsu T, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi K, Koganei K, Kunisaki R, Hirai F, Nagahori M, Matsushita M, Kobayashi K. The 2nd edition of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease: indication of anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 95. | Jung YS, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Long-term clinical outcomes and factors predictive of relapse after 5-aminosalicylate or sulfasalazine therapy in patients with intestinal Behcet disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:e38-e45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 96. | Hisamatsu T, Naganuma M, Matsuoka K, Kanai T. Diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014;7:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 97. | Jung YS, Cheon JH, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors for thiopurine maintenance therapy in patients with intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:750-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 98. | Sfikakis PP, Markomichelakis N, Alpsoy E, Assaad-Khalil S, Bodaghi B, Gul A, Ohno S, Pipitone N, Schirmer M, Stanford M. Anti-TNF therapy in the management of Behcet’s disease--review and basis for recommendations. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:736-741. [PubMed] |

| 99. | Travis SP, Czajkowski M, McGovern DP, Watson RG, Bell AL. Treatment of intestinal Behçet’s syndrome with chimeric tumour necrosis factor alpha antibody. Gut. 2001;49:725-728. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Hassard PV, Binder SW, Nelson V, Vasiliauskas EA. Anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody therapy for gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: a case report. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:995-999. [PubMed] |

| 101. | Naganuma M, Sakuraba A, Hisamatsu T, Ochiai H, Hasegawa H, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Hibi T. Efficacy of infliximab for induction and maintenance of remission in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1259-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 102. | Iwata S, Saito K, Yamaoka K, Tsujimura S, Nawata M, Suzuki K, Tanaka Y. Effects of anti-TNF-alpha antibody infliximab in refractory entero-Behcet’s disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:1012-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 103. | Kinoshita H, Kunisaki R, Yamamoto H, Matsuda R, Sasaki T, Kimura H, Tanaka K, Naganuma M, Maeda S. Efficacy of infliximab in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease refractory to conventional medication. Intern Med. 2013;52:1855-1862. [PubMed] |

| 104. | Lee JH, Cheon JH, Jeon SW, Ye BD, Yang SK, Kim YH, Lee KM, Im JP, Kim JS, Lee CK. Efficacy of infliximab in intestinal Behçet’s disease: a Korean multicenter retrospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1833-1838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 105. | De Cassan C, De Vroey B, Dussault C, Hachulla E, Buche S, Colombel JF. Successful treatment with adalimumab in a familial case of gastrointestinal Behcet’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:364-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 106. | Ariyachaipanich A, Berkelhammer C, Nicola H. Intestinal Behçet’s disease: maintenance of remission with adalimumab monotherapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1769-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 107. | van Laar JA, Missotten T, van Daele PL, Jamnitski A, Baarsma GS, van Hagen PM. Adalimumab: a new modality for Behçet’s disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:565-566. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Shimizu Y, Takeda T, Matsumoto R, Yoshida K, Nakajima J, Atarashi T, Yanagisawa H, Kikuchi K, Kikuchi H. [Clinical efficacy of adalimumab for a postoperative marginal ulcer in gastrointestinal Behçet disease]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2012;109:774-780. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Sylwestrzak G, Liu J, Stephenson JJ, Ruggieri AP, DeVries A. Considering patient preferences when selecting anti-tumor necrosis factor therapeutic options. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7:71-81. [PubMed] |

| 110. | Tanida S, Inoue N, Kobayashi K, Naganuma M, Hirai F, Iizuka B, Watanabe K, Mitsuyama K, Inoue T, Ishigatsubo Y. Adalimumab for the Treatment of Japanese Patients With Intestinal Behçet’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 111. | Melikoglu M, Fresko I, Mat C, Ozyazgan Y, Gogus F, Yurdakul S, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H. Short-term trial of etanercept in Behçet’s disease: a double blind, placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:98-105. [PubMed] |

| 112. | Watanabe S, Aizawa-Yashiro T, Tsuruga K, Kinjo M, Ito E, Tanaka H. A young girl with refractory intestinal Behçet’s disease: a case report and review of literatures on pediatric cases who received an anti-tumor necrosis factor agent. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:3105-3108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Katz S, Safdi M, Wolf DG, Baerg RD, Tremaine WJ, Johnson T, Diehl NN, Zinsmeister AR. Etanercept for active Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1088-1094. [PubMed] |

| 114. | Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, Houman MH, Kötter I, Olivieri I, Salvarani C. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1656-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 115. | Seyahi E, Hamuryudan V, Hatemi G, Melikoglu M, Celik S, Fresko I, Yurdakul S, Yazici H. Infliximab in the treatment of hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd-Chiari syndrome) in three patients with Behcet’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1213-1214. [PubMed] |

| 116. | Kim SW, Lee do Y, Kim MD, Won JY, Park SI, Yoon YN, Choi D, Ko YG. Outcomes of endovascular treatment for aortic pseudoaneurysm in Behcet’s disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:608-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 117. | Jung YS, Yoon JY, Lee JH, Jeon SM, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Prognostic factors and long-term clinical outcomes for surgical patients with intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1594-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Inoue N, Hisamatsu T, Imaeda H, Ishii H, Kanai T, Watanabe M, Hibi T. Analysis of clinical course and long-term prognosis of surgical and nonsurgical patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2848-2851. [PubMed] |

| 119. | Kasahara Y, Tanaka S, Nishino M, Umemura H, Shiraha S, Kuyama T. Intestinal involvement in Behçet’s disease: review of 136 surgical cases in the Japanese literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:103-106. [PubMed] |

| 120. | Han SW, Kim GW, Lee J, Kim YJ, Kang YM. Successful treatment with stent angioplasty for Budd-Chiari syndrome in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:234-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 121. | Kim WH, Choi D, Kim JS, Ko YG, Jang Y, Shim WH. Effectiveness and safety of endovascular aneurysm treatment in patients with vasculo-Behçet disease. J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 122. | Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical course of intestinal Behcet’s disease during the first five years. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:496-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 123. | Choi IJ, Kim JS, Cha SD, Jung HC, Park JG, Song IS, Kim CY. Long-term clinical course and prognostic factors in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:692-700. [PubMed] |

| 124. | Chung MJ, Cheon JH, Kim SU, Park JJ, Kim TI, Kim NK, Kim WH. Response rates to medical treatments and long-term clinical outcomes of nonsurgical patients with intestinal Behçet disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e116-e122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 125. | Kim JS, Lim SH, Choi IJ, Moon H, Jung HC, Song IS, Kim CY. Prediction of the clinical course of Behçet’s colitis according to macroscopic classification by colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:635-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Park JJ, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Outcome predictors for intestinal Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Med J. 2013;54:1084-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 127. | Jung YS, Yoon JY, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Influence of age at diagnosis and sex on clinical course and long-term prognosis of intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1064-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Kim DK, Yang SK, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Jo JY, Choi KD. Clinical manifestations and course of intestinal Behçet’s disease: an analysis in relation to diaesase subtypes. Intest Res. 2005;3:48-54. |

| 129. | Saadoun D, Wechsler B, Desseaux K, Le Thi Huong D, Amoura Z, Resche-Rigon M, Cacoub P. Mortality in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2806-2812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 130. | Yazici Y, Yurdakul S, Yazici H. Behçet’s syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:429-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 131. | Yasui K, Uchida N, Akazawa Y, Nakamura S, Minami I, Amano Y, Yamazaki T. Thalidomide for treatment of intestinal involvement of juvenile-onset Behçet disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:396-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 132. | Sayarlioglu M, Kotan MC, Topcu N, Bayram I, Arslanturk H, Gul A. Treatment of recurrent perforating intestinal ulcers with thalidomide in Behçet’s disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:808-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 133. | Postema PT, den Haan P, van Hagen PM, van Blankenstein M. Treatment of colitis in Behçet’s disease with thalidomide. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:929-931. [PubMed] |

| 134. | Kappen JH, Mensink PB, Lesterhuis W, Lachman S, van Daele PL, van Hagen PM, van Laar JA. Mycophenolate sodium: effective treatment for therapy-refractory intestinal Behçet’s disease, evaluated with enteroscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3213-3214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 135. | Iwata S, Saito K, Yamaoka K, Tsujimura S, Nawata M, Hanami K, Tanaka Y. Efficacy of combination therapy of anti-TNF-α antibody infliximab and methotrexate in refractory entero-Behçet’s disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:184-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 136. | Matsumura K, Nakase H, Chiba T. Efficacy of oral tacrolimus on intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:188-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chouliaras G, Deepak P, Grunert PC, Lodhia N, Sakuraba A S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH